Vertigo TOC | Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Films Home

LINKS TO SECTIONS OF THE ANALYSIS ON THIS PAGE:

You and I know who killed Madeleine

The Nightmare

I don't think Mozart's going to help at all

Ghosts

A Sea Change, The Tempest, and Twelfth Night

The Bohemians

He Dressed Me Like Her

Now we break almost entirely from the book, at the very end of the first act and throughout the rest of the second. In the novel, Roger (John) flees the site of Madeleine's death. He goes to see her husband, Paul, at their home. Paul is already frantic. Where is Madeleine? Roger was supposed to be with her, so where is she, Roger? Roger reassures Paul that she should be home soon. Unable to cope with Madeleine's suicide, Roger has decided to dissociate himself from the event entirely. He says that though he and Madeleine had made plans to meet that day, he didn't meet with her after all. This is Roger's first and only visit to the home of Paul and Madeline and it's now that he first sees the portrait of Pauline Lagerlac. Reassuring Roger that everything will be alright, that Madeleine is all right and will likely be home any minute, he leaves. He can't bring himself to tell Paul that Madeleine committed suicide.

Of course, when we know the plot we are aware that the reason Paul stands there, utterly white, in shock, is because he'd arranged for Roger to be a witness to the suicide, so there would be no doubt as to Paul's innocence. He knows that Roger was with Madeleine, but when Roger lies and says that he wasn't Paul is unable to call him out on it, to say that he was there, too, that he knows Roger was at the church.

In the book, Paul does become a suspect. Madeleine had been seen in a car with a man. What man? The reader who knows the plot will wonder if it was the real Madeleine with Paul or the fake Madeleine with Roger? That question is never answered. It could be that Paul was setting Roger up even to have been found guilty of her murder, if necessary, but Roger has gone and spoiled everything by doing an absolutely unforeseen thing and lying. Roger speaks to Paul only one more time, on the phone, after Madeleine's body has been found and her death is already being viewed with suspicion. Again, Roger assures Paul that everything will be all right for him and that he'll be back in touch with him. But he doesn't get back in touch with him. There's a turn in the war and Roger flees the German occupation. He doesn't return until four years later, and finds that Paul had become fed up with the questions lingering over Madeleine's death, attempted to go ahead and leave the area, only to be shot by the Germans. Yet another death for Roger to feel guilty about. He was responsible for the death of the officer who fell from the roof. He was the responsible for the death of Madeleine, unable to stop her from committing suicide. Now he's responsible for the death of Paul.

Leading man, Jimmy Stewart, has enough on his character's shoulders—adultery, mental illness—without John fleeing the scene of a murder and lying that he was never there. Well, he does flee the scene of Madeleine's death, but apparently in a state of trauma-induced amnesia, then goes to the police when he comes to his senses. So he endures an inquest. Is he guilty or not for Madeleine's suicide? We are made to feel the coroner is rough on him, but John deserves it even if Hitchcock wants us to feel the coroner is being harsh. No, John doesn't deserve being raked over the coals, by the coroner, for the police officer's death, the coroner blaming John and his vertigo for two deaths now. No, the audience knows he bears no responsibility there (which is one reason we feel the coroner is unfair), but John abandoned professionalism in his dealings with Madeleine. The inquest doesn't know the degree to which he abandoned professionalism, becoming romantically involved with her. Though the all male jury clears him of any responsibility, his reputation is destroyed.

|

|

John's guilt will be unsupportable. When Elster says, "You and I know who killed Madeleine", Elster is the one who does know and feels no guilt. But John? Though the jury has cut him loose, he will blame, at the very least, his vertigo for Madeleine's death. Hadn't he, realizing her dream was about San Juan Bautista, been the one to encourage her to visit the mission, assuring her that confronting reality would destroy her dream and free her? Instead, Madeleine had leaped from the tower. Elster says he's going to settle Madeleine's affairs, go to Europe and never return. John would have done well to go on vacation when Midge suggested it. John would have done well to cut himself loose from Elster and Madeleine when Midge laughed at the absurdity of Madeleine being possessed and then implied John was too personally involved when she asked of Madeleine was beautiful. Now, John's desperately in love with a dead woman who killed herself because he failed to save her, thus failing to save himself as well. How John now behaves, unable to speak, and then so catastrophically depressed that he must be hospitalized, I'm not confident is appreciated for how much of a betrayal this was considered to be against male competence, authority and stoicism.

Coroner: Mr. Elster, suspecting all was not well with his wife's mental state took the preliminary precaution of having her watched by Mr. Ferguson lest any harm befall her. And you have heard that Mr. Elster was prepared to take his wife to an institution where her mental health would've been in the hands of qualified specialists.

Mr. Ferguson, being an ex-detective, would have seemed the proper choice for the role of watchdog and protector.

As you have learned, it was an unfortunate choice. However, I think you'll agree that no blame can be attached to the husband.

His delay in putting his wife under medical care was due only to the need for information as to her behavior which he expected to get from Mr. Ferguson.

He had taken every precaution to protect his wife.

He could not have anticipated that Mr. Ferguson's weakness, his fear of heights, would make him powerless when he was most needed.

As to Mr. Ferguson, you have heard his former superior, Detective Captain Hansen, from that great city to the north, testify as to his character and ability.

Captain Hansen was most enthusiastic.

The fact that once before, under similar circumstances, Mr. Ferguson allowed a police colleague to fall to his death, Captain Hansen dismissed as an "unfortunate incident."

Of course, Mr. Ferguson is to be congratulated on having once saved the woman's life, when in a previous fit of aberration she threw herself into the Bay.

It is a pity that, knowing her suicidal tendencies, he did not make a greater effort the second time.

But we are not here to pass judgment on Mr. Ferguson's lack of initiative.

He did nothing and the law has little to say on the subject of things left undone.

Nor does his strange behavior after he saw the body fall have any bearing on your verdict.

He did not remain at the scene of the death. He left.

He claims he suffered a mental blackout and knew nothing more until he found himself back in his own apartment in San Francisco several hours later.

You may accept that, or not. Or you may believe that, having once again allowed someone to die, he could not face the tragic result of his own weakness and ran away.

That has nothing to do with your verdict.

It is a matter between him and his own conscience.

Now, from the evidence of the state of mind of Madeleine Elster prior to her death, and the manner of her death, and from the postmortem examination of the body showing the actual cause of her death, you should have no difficulty in reaching your verdict.

Gentlemen, you may retire if you wish.

Head Juror: We've reached a verdict.

Coroner: Thank you.

"The jury finds that Madeleine Elster committed suicide "while of unsound mind."

Your verdict will be so recorded. Dismissed.

Hansen: All right, Scottie, let's go.

Elster: Mind if I speak to him for a minute?

Hansen: No. Go ahead.

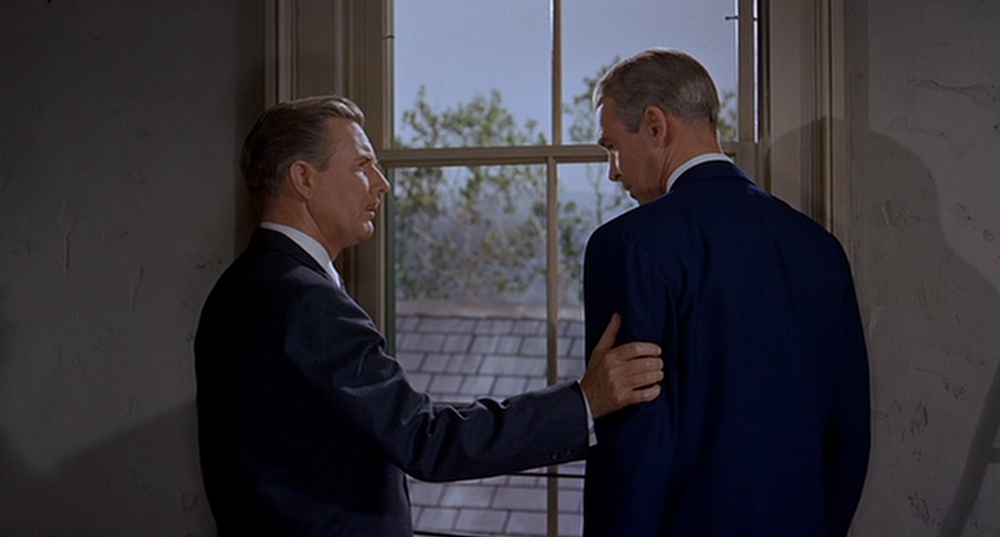

Elster: Scottie. Sorry, Scottie, that was rough. He had no right to speak to you like that.

It was my responsibility. I shouldn't have got you involved.

No, there's nothing you have to say to me. I'm getting out, Scottie, for good.

I can't stay here. I'm going to wind up her affairs, and mine, get away as far as I can.

Europe, perhaps. And I probably never will come back. Good-bye, Scottie.

If there's anything I can do for you before I go...

There's no way for them to understand.

You and I know who killed Madeleine.

Hansen: Come on, Scottie, let's get out of here.

John is pictured going to see Madeleine's grave. It was at Cypress Point that Madeleine had told him her repeated vision of her grave, an open one with a clean gravestone waiting for her, and how she would stare down into it. Hitchcock buries her at Cypress Lawn Cemetery, in Section I, Plot 409, the Flood family mausoleum not too distant. On the gravestone is carved, "Madeleine, wife of Elster Gavin", her birth name never mentioned in the film. The gravestone provides no closure for John. One might even sense how painful it would be for him that his Madeleine would be, on her gravestone, identified for eternity as "wife of Elster Gavin".

Hitchcock would have us observe John's dreams, now that he can't speak, so we may see how he feels via his subconscious.

The opening shot of the nightmare sequence returns us to a portion of the panorama we viewed during the chase scene across the rooftops, prior the officer's fall and John's dangling above the abyss. We are able to easily identify it by the SP, Southern-Pacific sign, which was also viewed during the chase scene. This shot of the panorama taken higher up than the rooftop chase shots, ReelSF.com states it was filmed from the Top of the Mark, the bar that John had joked with Elster about not being able to visit because of his vertigo, but there were plenty of ground level bars in San Francisco. Where Taylor Street is, and the place of the rooftop chase scene, is out of view, two to three blocks to the north and a a street behind. The Brockelbank building is out of view, a block directly north.

The Southern Pacific was originally in the Flood building that was built in 1907 by James Leary Flood as a monument to his father. The Southern Pacific also connects with the Portals of the Past monument as the Portals of the Past monument belonged to the home of Alvan Nelson Towne who was at one time vice president and general manager of the Southern Pacific system.

An aside, I'm completely confused by what appears to be at least a six story lit ad on the side of a building in the panorama. It looks so modern in appearance that I'm afraid my eyes are misinterpreting by reason of what this looks like to me "now" rather than what it might have looked like to me in 1958.

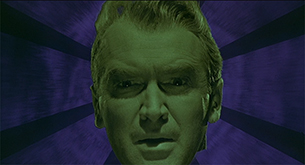

We are shown John lying in his bed, in which Madeleine had also lain after he rescued her from the bay. Cut to a close-up of him tossing and turning, his face tinted with a blue filter, then normal coloring, then the blue filter, the effect suggesting that the SP sign blinking on and off, in different colors, is responsible for the shifts, cycling several times between normal coloring and a purple filter before finally returning to the blue filter.

Out of the blue arises the bouquet of roses and blue forget-me-nots that Madeleine had carried, copying Carlotta in the portrait. The bouquet is also affected by the same seeming neon flashing. We see the flowers normally colored, then that neon green we will later associate with the Empire Hotel sign, but which is a green that already has appeared in the film, the same shade as the boxes at the flower shop and which is found in their vehicles. Now the flowers become a vaguer illustration of red and purple and blue and orange flowers against a black background. As they turn neon green, still against black, already rather amorphous, not detailed, they explode, coming apart, their bits and pieces unfurling and hurling at the camera. They assume a natural color then turn green then return to the natural color, this happening a couple of times more until they become jagged green splotches that exit the screen.

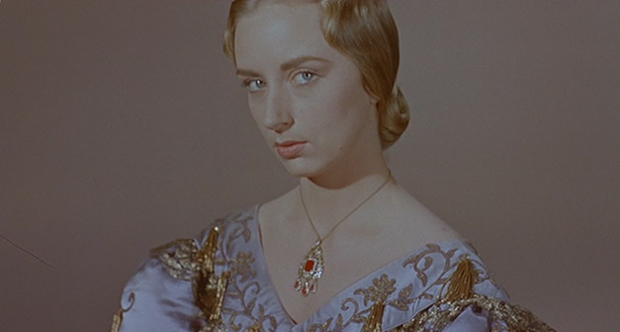

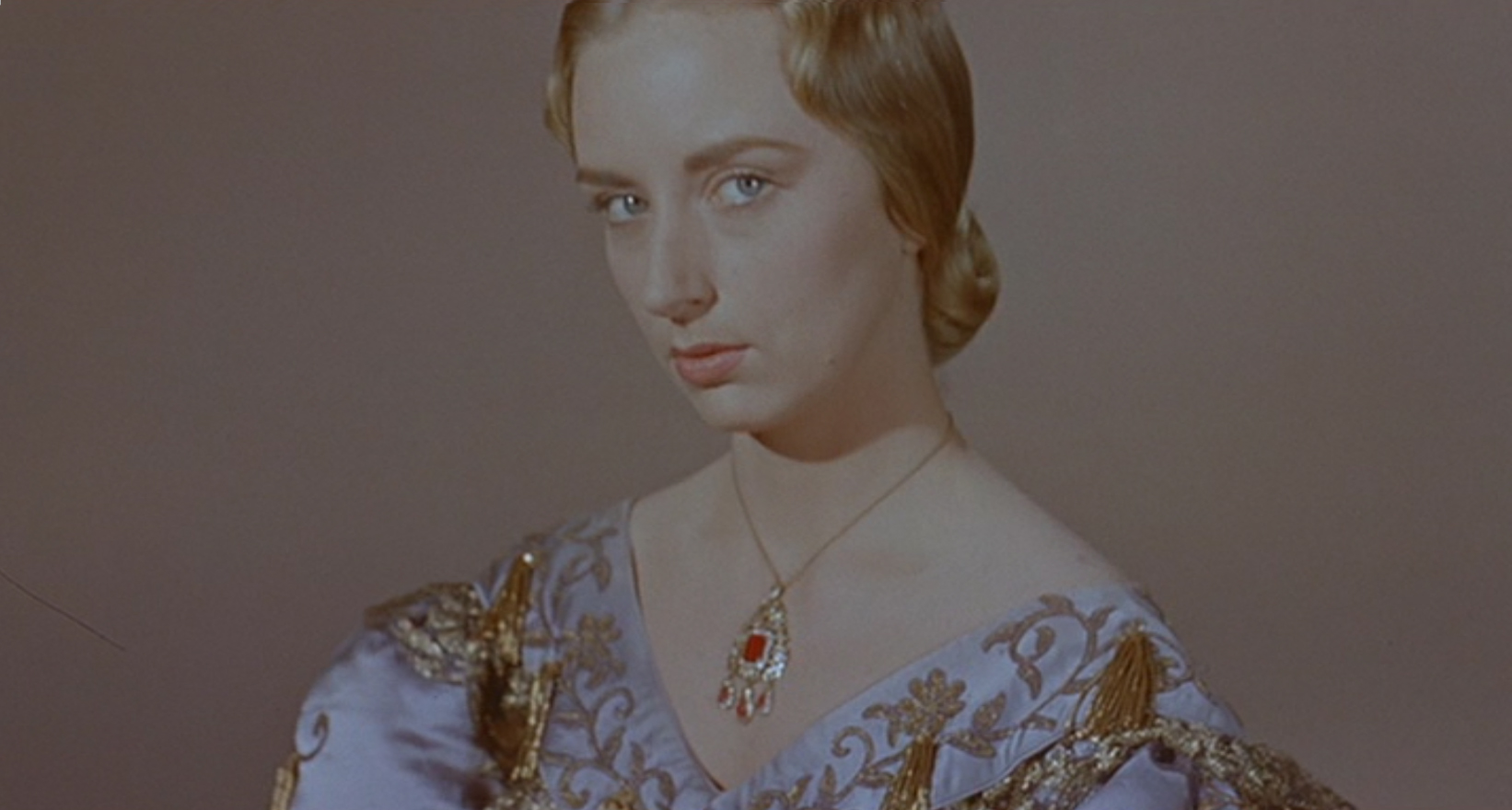

The nightmare returns to the inquiry, when Gavin went to speak to John as he stood beside the window, telling him he was going to Europe, and that they both knew who killed Madeleine. Gavin and John retain much their same positions, but between them now is Carlotta, played by Joanne Genthon, facing Gavin, his right hand on her left upper arm. Her head is lowered and she is in the shadows, but then she raises her head, the shadows lift, and the scene briefly turns blue then amber as she turns her head to look at John. The color returns to normal, her features in shadow again, then amber, normal color, amber, normal, amber, normal color, Gavin turning his head slightly so that he is also looking at John.

Next we see Carlotta's portrait but instead of the painting it is a head and shoulder's shot of Joanne Genthon playing Carlotta. Her eyes are tenaciously on the viewer. The screen flashes amber-red, normal color, amber-red, normal, as the camera zooms in on the necklace she wears with its bright red jewels.

The monochrome of Carlotta and the focus on the red jewel may remind us of the red filter over the woman's eye in the credits. Cut to a medium shot of John against black with a red filter. His expression is one of puzzlement, and he looks down as if he is gazing at Carlotta's necklace. He now walks forward, the screen flashing between normal color and the red filter. The camera zooms out as he continues to walk forward and the black background is replaced with a cemetery. He doesn't walk toward Madeleine's grave at Cypress Lawn. Instead he is approaching what is revealed to be Carlotta's grave, not exactly as it was at the cemetery earilier, many of the flowering plants around the grave seeming to have withered and died and its environment somewhat different. At the foot of the gravestone is the long open rectangle of the grave itself. John looks into it.

Black. It seems John has fallen into the grave. Next has appeared his cropped head (no body) occupying the center of the screen against 8 rays, the head appearing to travel or fall at a great speed, the background flashing between red and other colors, blue, sepia, green eventually, John's face also filtered with green, then his face abruptly disappears and we are left with the rayed pattern flashing different colors. Suddenly, against this rayed background, John's face reappears closer to the camera, large, fully occupying the screen, colored with the green filter. The face flashes between its normal color and others as the camera zooms in on it, then black occupies the screen.

As the black falls away from the screen it is revealed to be an illustration of a man's body falling toward the clay-tiled roof upon which Madeleine had fallen at San Juan Bautista, this flashing dull green and red. Before John's body hits the roof, the roof disappears, replaced by white, and John's body is left dangling against this abyss of white much like it is a puppet.

John starts up in bed as the horns scream.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|  |

|

With the flashing neon, should we think back to John's apartment, the Coloring Photographs book, and Roger's discussion, with Madeleine, in the book, about how his dreams were in black-and-white while her dreams were in color but they both met. Now John dreams in color and ostensibly we should be given new information in it.

To briefly review, and examine more closely a few points. we have been returned to the beginning, the vista that was behind the chase across the rooftops, but it is only a part of the panorama that was originally viewed, appearing to be more focused on the SP sign, as if it colors John's sleep, disturbing him.

In the neon green version of the bouquet of flowers there takes shape a form that annoys visually, it has five angles, a pentagon, and it may strike one that this is intended to be Carlotta's grave stone.

Perhaps the flowers of the broken bouquet become as amorphous as they do so that, when a single, small red rose appears amongst the other shapes, the spiral shape in the rose is accentuated for the viewer. The rose connects with the spiral of John's vertigo before the bouquet transforms into John revisiting the inquiry over Madeleine's death.

At the inquiry, Elster's hand had briefly rested on John's arm. In the dream, Carlotta takes the place of John, Gavin's hand instead on her arm. But this isn't the Carlotta of the painted portrait. She has become flesh and blood, a real woman, played by Joanne Genthon who, as far as I can gather, was only in a handful of films and always uncredited, just as she is uncredited here. (But perhaps she became known for being Carlotta's ghost, for which reason she played the paranormally green Banshee in the 1959 Darby O'Gill and the Little People, her last recorded role on IMDB.)

The movie has concentrated on the bouquet's association with Carlotta and Madeleine, as well her hairstyle, but the focus is being shifted to the necklace. After observing it, John tumbles into Carlotta's open grave at the Mission Dolores.

The pentagon shape in the bouquet annoyed me greatly, it jwasn't right, the way it stuck out, until I realized, oh, that's supposed to be Carlotta's gravestone. Looking at John's head before the eight-rayed figure that sometimes reminds of a web and other times of the rings of the great redwood at Big Basin, does it annoy visually that the left side (screen right) of John's neck has been retained in the visual of his face with the body cropped out? It annoyed me. Why leave that portion of his neck in? If the general public doesn't notice, an artist may notice and wonder at why this portion of the neck isn't also cropped out for it interferes with and disrupts the oval of the face, causing it to appear more like a sloppy special effect of a beheaded person haunting a castle in a bad horror film. Why, with all the money spent on this film, knowing this will be huge on the screen for all to see, wasn't that portion of the neck also clipped out? The answer may be found in the credits. This nightmare sequence is the beginning of the second act, and complements the credits at the film's beginning. If we refer back to the woman shown in the opening credits, in the first shot the lower screen right quadrant of her face filled the screen, including a portion of neck. The following shots moved to focus instead on her lips then eyes. John's face is intended to recall that unknown woman's face.

But is the woman in the credits unknown? In many ways she has very average, nondescript features, and despite this we know absolutely she is not Kim Novak and she is not Barbara bel Geddes.

It is easy, with the woman in the opening credits, to see who she is not in the film. I become less confident, however, when I compare her with Joanne Genthon, and try to determine if she is intended to be Carlotta Valdes, for the features are too nondescript, and they are subject to appear entirely different in another light situation. As freckles are retained, perhaps we can tell by these, but Joanne as Carlotta wears enough heavy make-up that, again, I'm unsure. However, the woman in the opening credits is being compared to John, and in the nightmare, in respect of Elster's hand upon her upper arm, Carlotta is taking John's place in the conversation Elster had with him after the inquest.

Why is the nightmare being used to reorient us to focus on Carlotta's necklace? What did John's subconscious pick up on that has eluded him otherwise?

|

|

John enters the hospital for his acute melancholia and Midge visits him. She tells him he's not lost, that "mother" is still there, referring to herself, as if this might be reassuring to him, and kisses his cheek. She tells the doctor that he was in love with Madeleine (unnamed, referred to as "the woman") and still is.

I'll get into Hitchcock and his mother issues later, I'm holding it off as long as possible as I personally find the idea of the Freudian Oedipal complex annoying, but it is an undeniable and often discussed theme in more than a couple of Hitchcock's films.

When one looks at the music Midge plays, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's Symphony #34, it ends with a tarantella, from tarantula, wolf spider, a dance that was part of a literal music cure for the supposed bite of a spider. Music would be played for the catatonic woman (sometimes a man), and as it grew more dynamic the person would rise and dance, becoming the spider that had possessed them, and I guess would be exorcised. Some trace the dances back to the bacchantes, a remnant of the suppressed cult. Ritualized dances were held in conjunction with the feast of St. Paul in Galatina. From Wikipedia, "the general and desperate agitation was dominated by the stylised cry of the tarantulees, the 'crisis cry', an ahiii uttered with various modulations."

It seems to me that the idea of the music cure refers to this.

Midge says, "I had a long talk with that lady in musical therapy, and she says that Mozart's the boy for you, the broom that sweeps the cobwebs away..."

Midge may doubt its efficacy but this has been brought up for a reason, the music directly associated with the spider and its web.

If we want to carry the spider theme further, looking at the spiral forms the movie uses to describe the vertigo, we would find in them an association with Arachne, the web-weaver, to whom the labyrinth actually belongs, which is why she is able to provide Theseus the means out of it, and an association is had with the legend of Tristan and Iseult for Tristan's death borrows from the death of Aegeus, Theseus' father. Theseus had ordered that Theseus' boat should hang a black sail, returning from his travail with the Minotaur, if he had died, and a white sail if he lived. In error, the boat flew a black sail and when Aegeus saw this he committed suicide in grief, throwing himself off a cliff. Tristan having sent for Iseult when he was ill, had asked that the returning ship fly a red flag if she was on it but, as with Theseus and Aegeus, the sail change was neglected.

When John plunges into Carlotta's grave in his nightmare, if we accept that the 8-rayed figure behind him may suggest a web, then there is also the 8-legged weaver of the web, the spider. Also, I have earlier discussed how in the book Madeleine was associated with a loup, a "wolf", when Roger (John) first viewed her in her gray suit and black veil of a hat and was reminded of a painting named La Femme au Loup.

Midge: Mozart, Wolfgang Amadeus. I had a long talk with that lady in Musical Therapy, Johnny, and she says that Mozart's the boy for you, the broom that sweeps the cobwebs away. Well, it's what the lady said. You know, it's wonderful how they have it all taped now, John. They have music for dipsomaniacs, and music for melancholiacs, and music for hypochondriacs. I wonder what would happen if somebody got their files mixed up. I brought a lot of other things, and you can see what you like. It shuts off automatically.

Oh, Johnny. Johnny, please try, try, Johnny. You're not lost. Mother is here. (A nurse looks in.)

Time? Okay. I'll be in again, John. You want me to shut that off?

John-O, you don't even know I'm here, do you? (Kisses his cheek.) But I'm here. (In the hallway)

Nurse, could I see the doctor for a moment?

Nurse: Doctor, Miss Wood. Won't you go in, please?

Doctor: Yes, Miss Wood?

Midge: Doctor, how long is it going to take you to pull him out of this?

Doctor: Well, it's hard to say. At least six months. Perhaps a year. It really could depend on him.

Midge: He won't talk.

Doctor: No, he's suffering from acute melancholia together with a guilt complex. He blames himself for what happened to the woman. We know little of what went on before.

Midge: I can give you one thing: He was in love with her.

Doctor: Oh, that does complicate the problem, doesn't it?

Midge: I can give you another complication: he still is. And you want to know something, doctor? I don't think Mozart's going to help at all.

Midge is the only one in the film who calls him John, Johnny as well, John being what he said was what intimate friends called him while acquaintances called him Scottie. Elster and Madeleine called him Scottie.

Act Two is almost entirely composed of scenes that are recycled from Act One, even before John is released from the hospital and begins his search for Madeleine's memory. We have observed this in the nightmare. The hospital scene revisits Midge having played classical music for John when he was at her apartment the day before he went to see Elster, and he had asked her to take off her Bach which he joked he found dizzying. It was in that scene at her apartment when John suggested he believed Midge thought he might crack up and rebelled against this, telling her not to mother him. At the hospital, when she kneels beside him, grasping his arm, John unresponsive, and begs him to try, to try, and tells him he's not lost, with John's inability to move, and Midge's urging him to try, telling him he's not lost, we are returned to the livery when John shows Madeleine a gray horse that can't move without being pushed, Madeleine tells John that it's too late, if he loses her he should know she loved him, and he insists he won't lose her.

John: Look at this. Here's your gray horse. Have a little trouble getting in and out of the stall without being pushed but even so...You see? There's an answer for everything. (She doesn't respond.) Madeleine, try. Try for me. (They kiss.) I love you, Madeleine.

Madeleine: I love you, too. Too late. Too late.

John: No, no. We're together.

Madeleine: No, it's too late. There's something I must do.

John: No. There's nothing you must do. There's nothing you must do. No one possesses you. You're safe with me.

Madeleine: No. It's too late. (She runs and he catches her.) Look, it's not fair. It's too late. It wasn't supposed to happen this way. It shouldn't have happened.

John: But it had to happen. We're in love. That's all that counts.

Madeleine: Oh, let me go! Please let me go!

John: Listen to me. Listen.

Madeleine: You believe I love you?

John: Yes.

Madeleine: And if you lose me, then you'll know I loved you and I wanted to go on loving you.

John: I won't lose you.

The gray horse in the livery becomes John who is unable to respond. John was entreating Madeleine to try, and Midge pleads with John to try. John had told Madeleine he wouldn't lose her, when she said he might. Midge insists to John he's not lost.

And it does seem to me that the audience, perhaps out of a certain embarrassment for John, takes too lightly his catastrophic depression that demands time spent in a hospital. In the 1950s this would have doomed him professionally and socially. In the film, his reputation is already ruined, but the hospital stay would have meant he would have been considered unsuitable for unemployment. In almost all circles, he would be defined as "John, who was in a sanitarium". If he couldn't handle the past, how would he be able to handle the future? He wouldn't be trusted to cope. As a man, he would also have been viewed as weak, emasculated, a problem already addressed jokingly at Midge's apartment when John wondered how many men might actually wear corsets. Hitchcock saw Jimmy Stewart as a man with whom an audience could sympathize, in whom they could see themselves, but not so much John in the hospital, the man who had completely broken down. His grief they could and did respond to, and they rally immediately to John's side when he begins his hunt for Madeleine's memory, but I think there's considerable denial of his hospitalization. As Roger, he wasn't hospitalized in the novel, he did see a doctor but Roger instead poured down alcohol in an attempt to deal with his trauma and anguish. In the 1950s, alcoholism was still viewed as a moral failing, and John's illness would have been viewed even more critically. Even with Madeleine, the dread was that she carried Carlotta's instability in her blood, which might doom her to suicide. Even as he built his case for her possession being real, Elster used the social stigma against mental illness as an excuse for not getting her treatment.

This is the last of Midge in the film. She leaves, Judy enters. I always miss Midge when she leaves as she was the only really likable character in the film, and though I don't watch films for likable characters her energy was a nice balance against that of John and Madeleine.

There was an alternative ending to the film, for the satisfaction of censors, but never intended to be used, which had Midge listening to the radio as it was reported how Gavin would soon be captured in Europe. Before I talk briefly about it, in preparation, I need to explore for a moment Midge's wardrobe. Her sweaters. The first time we see her she is wearing a yellow sweater. Pay attention to the collar. It's notched on each side, over the shoulders, so that it's in three pieces. This isn't apparent from the front, but it is from the side. Her second visit with Johnny, when she takes him down to the bookshop, she wears the same style sweater only it's white. The third time we see her, when she shows the painting to John, she is again wearing the same style sweater only in red. In the hospital scene, she wears the same style sweater but it's light blue. We also see her in the car the day she goes to John's and sees Madeleine leaving, but her coat is arranged so it's difficult to see what she wears. If we do get a glimpse of what's underneath, it might be a black sweater, I don't know.

|

|

|

|

What does this say about Midge, that she only wears the same sweater, over and over, but in different colors? I'm less interested in a psychological assessment but in how does this play into certain of the film's themes?

The alternative ending, the one not intended for use, broke this rule for Midge.

In the alternative ending for the film, she is in her apartment alone listening to the radio, as I've said above. Gavin is believed to be in the south of France and that there will be no trouble extraditing him. She doesn't wear one of her sweaters. She is instead wearing a light-colored robe of hers, her initials, MW, embroidered on the collar, and is barefoot. She turns off the radio when she hears footsteps on the stairs. John enters, without knocking, which I've already discussed, his familiarity, how they are like a couple in this way, though she hasn't the same visiting privileges at his place. In silence, she pours them both drinks and takes his to him as he stands before the window, then she goes and sits behind her artist drafting table. No words are exchanged between them. Hitchcock has returned us to near the film's opening when Midge and John had met at her apartment, when she was at her desk working, and he was exulting in getting rid of his cane, being freed from his corset, and asking her if she remembered a fellow named Gavin Elster, and she did not.

As it stands, the last we see of Midge is walking down the hospital corridor, no assurance had that John, who still loves "the woman" will ever get better in that regard, looking at the prospect of John being hospitalized for months to come. After which Hitchcock writes her completely out of John's life, as far as the audience is concerned.

The first shot in the hospital section was an establishing shot that showed the hospital's exterior, two nurses ascending the steps, and Midge's car out front. We had previously seen her car when she drove up to see Madeleine leaving after having been rescued from the bay.

We see pillars at the hospital's entrance, pillars ever to remind of Pillars of the Past. I saved mention of this opening shot because I wanted to pair it with the opening shot of the next section.

Reelsf.com identifies the hospital John has stayed in as St. Joseph's, facing Buena Vista park. If we look it up we find that once again, we have an association with the church, which would have been guessed by its name, the hospital having been founded by The Franciscan Sisters, and when we watch the nurses ascending the stairs out front we may even be reminded, by their white uniforms and caps, of the nuns in their black costumes at Saint Juan Bautista. It's a sunny scene and only allows the barest glimpse of the Buena Vista park neighboring it.

Opening this section, after the dusky interior of the hospital we again have a sunny San Francisco. The music is bright, injected with hope, as the camera pans over the city viewed from Twin Peaks, so as to encompass many of the locations we have visited. Out there somewhere is John's apartment, Midge's, and the Brocklebank. The dark area in the middle? That's Buena Vista Park, St. Joseph's hospital immediately neighboring on the screen right. To me, that dark spot of park, in relationship to the hospital, might remind of the abyss that John confronted at the film's beginning, opening under his feet on Taylor Street, and which we have felt haunting him this entire while. It reminds of the darkness that occasionally swallows the film, such as at the Argosy Book Shop, and when John and Madeleine visited the great redwoods, the towering canopies of which permitted no light. It is an expression of the deep depression John has experienced. Its darkness also refers to Tristan and Iseult and how their comprehension of darkness was that of truth, of release from rational daylight and its conventional aspirations, of the mystery of seeking the deepest union with the "other" that completes one under the auspices of the dark, of night, a union only hinted at briefly in life, conceived of as being completed only in death. In the middle of the vibrant city, lit by day, that dark stands like an island, ever present, around which all navigate.

Madeleine says, in the novel:

"...occasionally, I have quite definitely the impression I'm an old, old woman."

In the novel, acting the part of Madeleine, Renee (Judy), was intending to impress on Roger her having been possessed by her great-grandmother, Pauline. The book also has Roger haunted by old things, while the film instead starts with mother issues, John snapping at Midge when she thinks of his health, telling her to stop mothering. This wasn't the only film Hitchcock did in which mother issues featured. Maybe Hitchcock just thought mother issues made for a sell-acious plot. Maybe he thought everyone had Oedipal issues. Maybe he had mother issues. I don't know. Freud took a complex myth--in which Oedipus does everything he can to avoid his projected destiny, gouges out his eyes when that destiny is avoided, Jocasta committing suicide--and absurdly simplified it and used it to name his eventual explanation for why so many women were reporting in the secret confessionals of the psychiatrist's office that they had been sexually abused as children, he twisting it so that it was children who desired their parent and were projecting those desires with false fantasies and dreams. With both the book and the film, Madeleine is confused with the great-grandmother, through the notion she is being possessed by her, so that it becomes impossible to say where the "idea" of Madeleine begins and ends, and where the "idea" of her great-grandmother begins and ends, the two having been blurred together (and only for reason of conning Roger). The boundaries are blurred, especially as we don't know who either one was. We know Madeleine looked like Judy masquerading as Madeleine. We know that Judy masquerading as Madeleine imitated Carlotta. John won't care for Judy, but he never met the real Madeleine, and was most involved with the Madeleine who pretends to be possessed by Carlotta, so who was he in love with? Carlotta? Madeleine? Or Madeleine as partly the expression of the mystery of the eternal, what can never die?

When John, unable to let go of dead Madeleine, returns to places to which he'd followed her, the first ghost of Madeleine we see is an elder woman dressed in an outfit that resembles what Madeleine wore on the day they went redwooding (Great Father Tree, you took no notice of me when I died) and has the elder woman literally owning Madeleine's ride, sold to her by Elster when he left town. John, when he thought Midge mothered him with her concern, rebelled, and he certainly has no desire for this elder incarnation of not-Madeleine. John demands of the woman where she got the car and when the woman begins to talk about how horrible it was what happened to Elster and his wife, he turns and walks away.

Notice that whereas the cars out front of the apartment building were originally parked perpendicular to it in the scenes with Madeleine, now they are parallel to the building and face off with the "One way" sign, opposing it. My mind turns to the tabula scalata, an image which, not dissimilar to a fan in construction, has a companion immediately embedded at a right angle, and how these were used for revelations and puzzles, such as a portrait being paired with a death head, or age paired with youth. An interesting one uses as its two portraits one of a Jacob Van Hoorn, the other of his bride, Jacoba Van Selstede, these portraits supposedly comemorating their marriage in 1735, when Jacob was 97 and Jocoba was 23. In the tabula scalata version of these portraits we have thus not only the pairing of the man and the woman, but old age and youth. I've only seen one copy of the tabula scalata on the internet, while there seem to have been numerous copies made of the original portraits, and I wonder at their popularity when in ancestry sites I can find no valid record that a Jacoba van Selstede and Jacob van Hoorn ever existed. Perhaps they did and i've somehow overlooked it. Let's say they did exist, it still doesn't explain the popularity of the portraits so that they were at one time expressed as a tabula scalata, which suggests a meditation on youth and old age, or on death. I've even wondered if Jacob van Hoorn was being expressed as marrying, in death, that which spiritually completed him.

|

|

|

|

John returns to Ernie's, and we see when he opens the front door how the red of the stained glass is not red stained glass but is translucent, the red that had appeared to be stained glass is instead Ernie's interior wallpaper. Inside, he sees another of Madeleine's ghosts. She wears an outfit that, though it is a suit, is intended to remind of the white coat we just saw on the elder woman. The suit, however, has a voluminous white shawl collar, while it is otherwise black, and she wears white gloves. It's like a negative, an inversion of the white coat, black scarf and gloves. The man who is with her in some respects could remind of a young Jimmy Stewart. The reason I think it may be intentional that Hitchcock has here a man who resembles a young James Stewart is that this couple being close in age to one another addresses the age disparity between Madeleine and John. We will have other occasions to be reminded of the age difference between Madeleine and John when he comes across Judy and keeps company with her.

At Ernie's, for some reason Hitchcock has frozen its environment. The people have changed, but the flowers are the same. We know that the pink rose on the table under the tabula scalata is not fake, its imperfections mark it as real, and it is unchanged.

At the Palace of the Legion of Honor, John approaches a young woman seated before the Carlotta painting who in no way resembles Madeleine. Her hair isn't even blond, it is red. Taken aback, she looks up at him, wondering why he hovers over her. John may be out of the hospital but he has lost any idea of boundaries.

|

|

|

|

|

|

John goes to the flower shop where, looking at the bouquets in the window, surrounded by the green that is so strongly associated with the ghostly green resurrection of Madeleine at the Empire Hotel, he sees Judy. Unlike the elder woman, or the young woman at Ernie's, she's not dressed like Madeleine. Her manner is unlike Madeleine's. Her make-up, her hair, her social class aren't Madeleine, but she so reminds him of Madeleine that he follows her to where she lives, the Empire Hotel. She enters, and John watches as she opens the window to her room in an upper floor--just as Madeleine had done at the McKittrick Hotel where she vanished, and the proprietor had said she hadn't even seen her enter that day, just as Madeleine hasn't entered this hotel, only a woman who reminds John of her.

Hitchcock has John visit almost all the places to which he followed Madeleine that first night and day, but he doesn't take him back to the actual McKittrick Hotel, which was supposedly the home built for Carlotta, he replaces it with the Empire. John doesn't visit Mission Dolores and its cemetery, but he saw Carlotta's grave in his nightmare.

Beside the Empire Hotel is Twelfth Knight, which appears to be a club in the same building but perhaps located beneath in the basement. Twelfth Night was a Shakespeare play and it seems a good time to briefly look at another Shakespeare reference that occurs when John is seen first visiting Midge's apartment. On the wall behind him we see two sketches on which Midge has been apparently working. One appears to be of a man in a Marine's dress uniform. Beside it is a sketch of a woman in a blue dress. Over this are the words "A Sea Change". We are never given a good look at the full sketch but she appears to be stretching up to kiss or speak with a man.

|

|

"A sea change" refers to The Tempest, spoken by Ariel when he is leading Ferdinand to Miranda, making him believe that his father has perished in a ship wreck of which, as far as Ferdinand knows, he is the only survivor. Prospero had caused those on the ship to believe it had wrecked in a storm. Aside from Ferdinand, the son of the King of Naples, there are two other groups of "survivors" who believe all else have died. At play's end, they learn that no one has actually died and that the ship didn't wreck after all.

Full fathom five thy father lies;

Of his bones are coral made;

Those are pearls that were his eyes;

Nothing of him that doth fade,

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.

Sea-nymphs hourly ring his knell:

Ding-dong.

Hark! now I hear them — Ding-dong, bell.

A sea change has come to mean something that has undergone an otherworldly transformation.

What does Hitchcock intend by its inclusion? Does this connect with Madeleine's leap into the sea? Or does it have to do with the ghastly play that has been staged by Elster and Judy? The Madeleine that John knew, the counterfeit Madeleine, who he had believed to have died, is alive.

Shakespeare's Twelfth Night play also concerns a brother and sister, twins, who were traveling by ship. When it wrecks, they each believe the other has died. Viola disguises herself as a man, Cesario, and goes to work for Duke Orsino. The Duke is in love with a woman named Oliva (a permutation of the name Viola) whose brother has recently died and is in mourning. The Duke employs Viola-Cesario to act as his intermediary and profess his love to Olivia, but Olivia falls in love with Viola-Cesario, while Viola has fallen in love with the Duke. Sebastian, Viola's twin brother, survived the shipwreck after all and shows up. Sebastian looks like Viola-Cesario and Olivia, having confused the two, asks Sebastian to marry her, and Viola ends up with the Duke. It seems the play was called "Twelfth Night" as the Twelfth Night festival involved a brief upsetting of societal roles, servants dressing as masters and men as women and women as men.

In both plays there's confusion that leads to the belief a person is dead when they're not, and in Twelfth Night Viola plays at being someone she's not, a man who becomes confused with her twin brother, Sebastian, by Olivia. So there is a deception of identity. One may wonder about the idea of gender confusion, where that occurs in Vertigo, when it is very evident throughout. Judy, playing Madeleine, is dressed by Elster. She even says that, "He dressed me like her." Then John also forces Judy to dress a certain way, like Madelaine, telling her he knows what would look well on her. He never does make love to Judy-as-Judy. He is only able to be romantic with the Madeleine who has been designed by men, by Elster and by John.

In their initial meeting, in the book, Paul brings up to Roger a film they had seen together, back in the old days.

The impression I got was that she was afraid...Look here: do you remember—this'll make you smile—a German film called Jacob Boehme we saw at the Ursulines back in the twenties?...Do you remember the expression on the mystic's face when he was caught in a sort of visionary trance? And he tried to find excuses and hide the fact that he had visions...Well, Madeleine's face looked like that German actor's. A bewildered, groping look; I might almost say a drunken look...

The subject of Boehme is never brought up again in the novel, so it's a curious reference, and of note that the introduction to Madeleine's trances, at least in the book, has less to do with ghost stories and possession than mysticism. A relationship may also be drawn with Roger spending the most part of the second half of the novel sick-drunk.

I have looked for a 1920s film on Jacob Boehme and been unable to find mention of it, so I believe it's fictitious. There are several paintings that Roger speaks of in the novel that are real. But what about this movie? Is it intended to be a real fiction, as in a movie that they actually saw? Or is Paul telling Roger the story of something they supposedly did together but never happened? The Ursulines theater was real, but not the movie.

What seems to me, at first glance, to be a possible link between Vertigo, the originating novel, and Jacob Boehme, was Boehme's seeming belief that The Fall was essential to the evolution of the Universe and God. Which means adjusting so that we look at Roger's fear of heights and his vertigo so that we approach them on a very spiritual level. It's very lazy of me to do but below is Wikipedia's attempt at a sketch of those beliefs

According to F. von Ingen, to Böhme, in order to reach God, man has to go through hell first. God exists without time or space, he regenerates himself through eternity. Böhme restates the trinity as truly existing but with a novel interpretation. God, the Father is fire, who gives birth to his son, whom Böhme calls light. The Holy Spirit is the living principle, or the divine life.

However, it is clear that Böhme never claimed that God sees evil as desirable, necessary or as part of divine will to bring forth good. In his Threefold Life, Böhme states: "[I]n the order of nature, an evil thing cannot produce a good thing out of itself, but one evil thing generates another." Böhme did not believe that there is any "divine mandate or metaphysically inherent necessity for evil and its effects in the scheme of things." Dr. John Pordage, a commentator on Böhme, wrote that Böhme "whensoever he attributes evil to eternal nature considers it in its fallen state, as it became infected by the fall of Lucifer... ." Evil is seen as "the disorder, rebellion, perversion of making spirit nature's servant", which is to say a perversion of initial Divine order.

Hitchcock never mentions Jacob Boehme, a kabbalist and alchemist whose spiritual interpretations were highly influential, but there is the Pillars of the Past that Madeleine goes to stare at, according to Elster, a painting of which was for years kept in the Bohemian Club. There's also Elster's yearning for the gay old bohemian days, missed by him for their freedom and power. In the book, Roger himself envies Paul's privilege, power, and wealth, things borrowed from Madeleine. WIthout Madeleine's wealth and her industrial/social connections, he'd be nothing. I've assumed that John has this same envy.

The Bohemian Club is a mens' social club that is different from the Pacific Union Club where Elster meets with John, but is like it in that they are both elite mens' social clubs and overlap. James Leary Flood, who married the dancer, Rose Fritz, and had the illegitimate child, Constance, by another dancer, Eudora, was a Bohemian Club member, and of course would have been a member of the Pacific Union Club, the clubhouse once having been the Flood mansion.

A motto of the Bohemian Club is "Weaving spiders come not here," from Midsummer Night's Dream, Act 2, Scene 2, and means that this is a place where political and business concerns are left at the door. They are famously known for their theatrical Cremation of Care (the cares of the world) at their midsummer Bohemian Grove retreat, the Cremation of Care reminding how they are to leave business concerns and the affairs of the world outside that place.

In Act 2, Scene 2, Puck, a sprite, has been ordered to dose Demetrius' eyes with a magical potion that will cause him to fall in love with whomever he first sees upon waking. This has been done so that he will fall in love with Helena, who loves him, while he rebuffs her. Puck doesn't know what Demetrius looks like and accidentally doses Lysander, who, waking, falls in love with Helena who instead loves Demetrius. Demetrius is later dosed with the same potion and falls in love with Helena, and Lysander is dosed again so that he falls back in love with his original love, Hermia. As far as Vertigo is concerned, what seems most salient is the idea of the love potion, for a love potion is also a part of the legend of Tristan and Iseult, and is alluded to in the film. However, I've thought that another powerful connection is the fact that John gets in as much trouble as he does because he mixes business with friendship, and Elster has asked him to do so. He has asked John to take the job of following Madeleine because he is a friend. He won't accept anyone else. John had been set against taking the job but decided to because it was for a "friend", though Elster is not a friend, he is simply someone John used to know. John thus opens himself to being used. Then, when following Madeleine, he abandons any professionalism and becomes emotionally involved with her.

A mascot of the Bohemian Club is the owl. Let's return to when John follows Madeleine to the flower shop. She takes a turn into an alley next it and enters through a rear door--it's that scene in which he passes through the dark entry and is greeted with an explosion of color, opening a door onto another world, a veritable paradise. Judy Garland of Kansas has landed in magical Oz.

When John, in the second act, returns to the flower shop, where does he see Judy/Madeleine? She is crossing over the alley into which Madeleine had turned when he had followed her, on the first day, to the shop.

What do we see beyond? Owl Rexall drugs. Hitchcock had avoided fully showing this when John had followed Madeleine to the shop. There are some simple color associations that might draw our attention to it. When John had followed Madeleine, we'd seen on the right side of the street, partly covering the sign, the flower shop's van, two-toned green, an orange-red VW immediately behind it that's the same color as the owl sign. There's also an orange-red vehicle before the green van. Then when John sees Judy, an association with that flower shop green is made by having another van, two-toned, of the same green colors, parked in front of Owl drugs. Judy's outfit is in the same dark green as we see on the van. This is, rather, John's second tripping into Oz--the first time via Madeleine, and this time via the earthier Judy.

There's also Hitchcock's choice to take John and Madeleine into the forest of the great redwoods, reminding of the Bohemian Club's retreat at Bohemian Grove. Coincidentally, during the drive, we see smoke in the forest..

Having followed Judy to her hotel, John is able to identify what room she lives in because he's seen her open her window. He goes up to speak with her and she accuses him of following her, which he has done. When she does let him in, she backs up in such a way that her hands can quickly grab up her phone for help if need be. She worries she might be in trouble. But with her IDs and her photos of her family, she appears to prove to John that she's Judy Barton from Salina, Kansas.

|

|

She accepts a dinner date, but when he leaves she turns to the camera and Hitchcock gives us a flashback that shows she was indeed at the bell tower. There had been two Madeleines and Gavin Elster threw one off the tower to her death, which means Judy is the one who had survived, a fake Madeleine. Elster had murdered his wife, with Judy as an accomplice.

|

|

|

|

She prepares to flee, but then writes a confessional letter to John in which she admits her love for him and says he has no reason to feel guilty over Madeleine, for he was a victim of Elster's plan to murder his wife. Judy does not go so far as to state she was guilty, instead she speaks of herself as Elster's tool. She may have a difficult time accepting her own guilt--she may not even connect with it, just as Renee, in the novel, seems untroubled by the part she played in Madeleine's death. Then, rather than leaving, Judy decides to stay and try to win John over to loving her rather than Madeleine. She tears up the letter and throws it away. Just as Hitchcock has revisited, in this second section, places to which John had followed Madeleine, though situations and intentions are different he once again has Judy writing a letter to John. In the first letter she said she hoped they would meet again. When John echoed that desire, she said they already had and gone to her car, John following and urging they spend the day together. They ended up visiting the redwood forest and Cypress Point. Again, Judy states she had hoped to meet John again, then rather than confessing and leaving she decides to stay and hopes that John will forget the past.

|

|

Note the fan that prominently hangs from the lamp in Judy's hotel room. For me, this recalls the fan and the tabula scalata at Ernie's. So one could look at Judy now being fully revealed as Madeleine's opposing image.

In the book, Roger is watching a newsreel of celebrations over France's emancipation from Germany, and he sees a woman who looks like Madeleine. Which turns out to be the inspiration for the book, why it was written, because of all the losses that were inflicted by the war, all the many dislocations of family and friends. One of the authors, Thomas Narcejac, thought he saw someone he knew in a newsreel and this sparked the story of Madeleine.

Roger (John) believes he sees Madeleine celebrating in a newsreel. She's dead, but as in the film she is somehow not dead, not for him, not emotionally, he must find her. Orpheus pursuing Eurydice. He travels to the hotel where he believed he saw her in the newsreel, and there she is. Her name, however, is Renee, and she insists she knows no Madeleine. She is, as in the film, a completely different person in attire, tastes, manner, disposition. She lives off wealthy men and has just been dropped by another one, so John stays there and invites her to live with him. She does so, but this is no budding love affair, not on Renee's part. She makes it obvious to Roger that she dislikes him. And, Roger? He's so drunk-sick that he can scarcely do anything, but he does pester Renee to redo herself as Madeleine, her hair, her clothing, her make-up. She resists but then eventually gives in, explaining that she did so in order to erase herself, as Renee, in his mind, and leave him only with the obsession and memory of Madeleine/Pauline when she splits from him. He badgers her--isn't she Madeleine? By now he knows she must be. Finally, she relents and admits that she is. She tells him the whole story about how he was used. She does not plead that she stayed with him, despite the dangers, because she loved him. No, she hated him. When she asserts her own identity, that she is Renee, though she played Madeleine, Roger strangles her to death.

Those are some very big differences between the book and the movie, and yet in certain important respects (except for the strangling) not so big at all, not when it comes to John pursuing Madeleine's ghost, and then setting out to transform Judy into Madeleine. But what of the love story? Hitchcock has Judy in love with John, which is a significant departure from the book and sets it up for the audience to perhaps develop some sympathy for Judy, despite the fact she participated in a murder, she wasn't forced to do it. Should we trust her when she says she loves John? Does the fact that she sat down to write that letter to John, instead of simply fleeing, prove that she loves him, for she didn't have to do so, she didn't have to confess? Remembering that she has the gray suit, the murder suit, in her closet, that she seems to have kept it as a memento, shouldn't we wonder at how her psyche is structured that daily opening her closet to see that suit doesn't fill her with horror?

I'm going to assume that Hitchcock does want us to like Judy, to feel compassion for her, to accept her as loving John, else he wouldn't have had her write the letter, which she didn't have to do, she could have fled without confessing. Hitchcock didn't want a Renee who is an entirely unsympathetic character. And, unlike in the book, where we are kept guessing until the end if Renee is actually Madeleine, Hitchcock wants the audience to confidently know what John does not. That Judy is Madeleine. Because we know this, and have been shown Elster throwing Madeleine from the tower, the abuse that John inflicts on Judy, as he coerces her into changing, will be largely overlooked by the audience, for we know that Judy was the counterfeit Madeleine with whom he fell in love. We may feel sympathy for Judy, because she loves John, but we will feel also a touch more sympathy for John, because he was betrayed and is still being betrayed. Judy is still conning him.

Judy: Well? What is it?

John: Could I ask you a couple of questions?

Judy: What for? Who are you?

John: My name is John Ferguson.

Judy: Is this some kind of Gallup Poll?

John: No, no. There are just a couple of things I'd like to ask.

Judy: You live in this hotel?

John: No. I happened to see you when you came in, so l...

Judy: Yeah, I thought so. A pickup.

Well, you've got a nerve, following me into the hotel and up to my room.

Now, you beat it. Go on and beat it.

John: No, please. I just want to talk to you.

Judy: Listen, I'm gonna yell in a minute.

John: I'm not gonna hurt you. Honest. I promise.

Please. Just let me talk to you.

Judy: What about?

John: You.

Judy: Why?

John: Because you remind me of somebody.

Judy: I heard that one before, too.

I remind you of someone you used to be madly in love with but then she ditched you for another guy and you've been carrying a torch ever since.

And you saw me and something clicked.

John: You're not far wrong.

Judy: Well, it's not gonna work, so you better go.

John: Please, let me come in. You can leave the door open. I just want to talk to you. Please.

Judy: Well, I warn you, I can yell awful loud.

John: Oh, you won't have to.

Judy: Well, you don't look much like Jack the Ripper. What do you want to know?

John: I want to know your name.

Judy: Judy Barton.

John: Who you are.

Judy: I'm just a girl. I work at Magnins.

John: How do you happen to be living here?

Judy: It's a place to live, that's all.

John: No, but you haven't lived here long?

Judy: Yeah, about three years.

John: Well, where did you live before?

Judy: Salina, Kansas!

Listen, what is this? What do you want?

John: I just want to know who you are.

Judy: Well, I told you.

My name is Judy Barton. I come from Salina, Kansas.

I work at Magnins and I live here.

My gosh, do I have to prove it? All right, mister, my Kansas driver's license.

Judy Barton, number Z296794. 425 Maple Avenue, Salina, Kansas.

See the address on this one? It's this place right here.

A California license issued May 25, 1954.

You want to check my thumbprints? You satisfied?

Whether you're satisfied or not, you can just beat it.

Gee you have got it bad, haven't you? Do I really look like her? She's dead, isn't she?

I'm sorry, and I'm sorry I yelled at you. (Showing him photos.) Yes, that's me with my mother. And that's my father. He's dead. My mother married again, but I didn't like the guy so I decided I'd see what it's like in sunny California. Been here three years.

Honest.

John: Will you have dinner with me?

Judy: Why?

John: Well I just feel I owe you something after all this.

Judy: You don't owe me anything.

John: Then will you? For me?

Judy: Dinner and what else?

John: Just dinner.

Judy: Cause I remind you of her?

John: Because I'd like to have dinner with you.

Judy: Well, I've been on blind dates before.

Matter of fact, to be honest, I've been picked up before. Okay.

John: All right, I'll get my car. I'll be back for you in half an hour.

Judy: Oh, no, you better give me time to change and get fixed up.

John: An hour?

Judy: An hour?

John: Okay. (He leaves and she sits and writes him a letter.)

Judy: Dearest Scottie...And so you found me. This is the moment that I dreaded and hoped for, wondering what I would say and do if I ever saw you again. I wanted so to see you again, just once. Now I'll go, and you can give up your search.

I want you to have peace of mind. You've nothing to blame yourself for. You were the victim. I was the tool and you were the victim of Gavin Elster's plan to murder his wife. He chose me to play the part because I looked like her. He dressed me up like her.

He was quite safe because she lived in the country and rarely came to town.

He chose you to be the witness to a suicide. The Carlotta story was part real, part invented, to make you testify that Madeleine wanted to kill herself.

He knew of your illness. He knew you'd never get up the stairs to the tower.

He planned it so well. He made no mistakes. I made the mistake. I fell in love.

That wasn't part of the plan. I'm still in love with you, and I want you so to love me.

If I had the nerve, I'd stay and lie, hoping that I could make you love me again, as I am, for myself, and so forget the other, and forget the past. But I don't know whether I have the nerve to try.

Continue to Part 5

December 2021. Approx 11,200 words or 22 single-spaced pages of text.

Return to the top of the page.