Vertigo TOC | Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Films Home

LINKS TO SECTIONS OF THE ANALYSIS ON THIS PAGE:

Credits

The Fall

You were the one that called off the engagement, you remember?

The things that spell San Francisco to me are disappearing fast

Portals of the Past

We're dining at Ernie's first

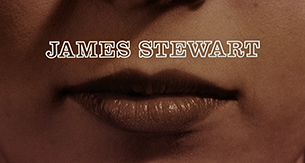

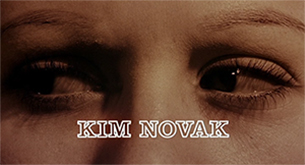

Vertigo opens with a monochrome color-tinted close-up of the lower left quadrant (screen right) of a woman's face, showing the cheek and part of her ear, the face not split symmetrically so we see a little more than half of her nose and mouth. As the film is resplendent with color it's puzzling that the woman is viewed only in sepia. As the credits open, we don't wonder who the woman is, but we may later, a subject I cover in the nightmare section. If we are in the audience in 1958, watching this on the big screen, what we're viewing is legitimately high art and has powerful, visual impact, extra-ordinary, surreal.

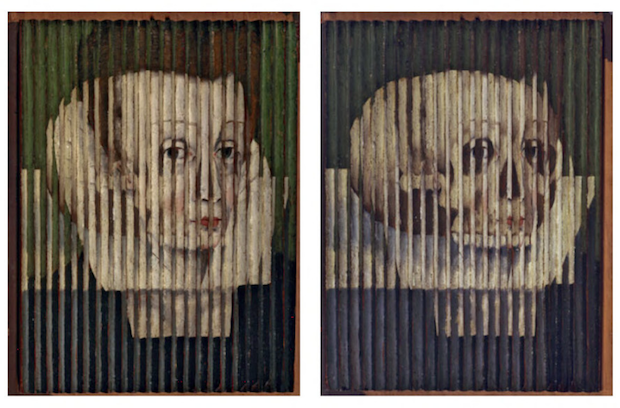

The camera shifts to focus on the woman's mouth, which slightly moves as the name "Jimmy Stewart" appears above it. There is no reason to show the woman's mouth move in this manner, subtly yet obvious, so take note and perhaps compare this with how Jimmy Stewart, as John, sometimes moves his mouth in the film. In this extreme close-up, the camera pans up to focus on her dark eyes, which glance right and left as the name "Kim Novak" appears, and though this might connote wariness, keep these side to side glances in mind when I later discuss the appearance of a tabula scalata in the movie. The camera shifts now to show only the woman's shadowed right eye, "In Alfred Hitchcock's" appearing below. The camera zooms in on her eye, now layered with a red filter and lightened so that we may see it more clearly as she opens that eye wide to a blast of horns, as if in horror, and Vertigo appears in the pinpoint dilation of her pupil. The word Vertigo expands to take up the screen then soars out of it as a pink galactic spiral with two arms appears in the place of the pupil. The woman fades into black as the spiral grows and consumes the screen with a veritable web of spiraling arms. This pink spiral is replaced by a cyan spiral of the same type which also grows and consumes the screen before being replaced with another pink graphic. A number of figures follow, all of which can be described as characterized by webs of loops or spirals, the music also revolving, composed largely of ascending and descending scales, the repetitive nature of which might be trance-inducing if not occasionally broken by the intrusion of a blast of horns or gesture of melody. The graphic design is the magic of Saul Bass, who would state that his goal in his treatment of title sequences was to "try to reach for a simple, visual phrase that tells you what the picture is all about and evokes the essence of the story". Working in conjunction with Saul Bass, experimental film artist, John Hales Whitney Sr., created the animations. We can rightly assume that these spirals symbolize the vertigo of the main character, however they've also to do with The Eternal Return aspect of the story, also visually expressed in the hairdo of the character of Carlotta-Madeleine, and which I will discuss most fully in Part Five.

|

|

|

|

|

|

After the webs of spirals backing the credits, if we have become fully immersed in them, it's disarming, Hitchcock's cut to a single black bar that slices the screen horizontally, the midnight blue shadings of the background out of focus. We are given time to look, to ponder what may as well be an abstract painting (and perhaps we are of a mind to receive it abstractly after the film's opening), to consider what this means, to not be able to guess, then a hand reaches up from below and grabs the bar. As the camera pulls back, the bar is quickly revealed as belonging to a ladder that leads to a roof, a city skyline beyond. This opening is so dark that any light, such as from neon or in apartment windows, seems veiled, obscured. Much of the film is quite dark, and many of the screengrabs on the internet don't reflect this, are lightened. I have preserved the darkness of the film in my screengrabs from the Universal Legacy Series TCM release, in which this darkness is confirmed in commentary on the movie. My proposal is that the manner in which the film uses dark and light has to do with the influence of Wagner's Tristan and Isolde, composer Bernard Herrmann using the "Liebestod" theme ( liebe meaning love, and tod meaning death). In the opera, Tristan and Isolde reject daylight's rational world, the light of reason that would keep them apart, the light of the rational and conventional that promotes honor and fame, power and profit, light which is pain and deprivation of delight, and which brings for them the longing for the dark and the night that belongs to lovers, twilight that obliterates the vanities and delusions of day. Where they will be united is in the night, and in death. The struggles with light and dark are expressed throughout the film, John seeking rational explanations while desiring the mysterious.

A man in a white shirt, light tan pants, and light-colored sneakers, vigorously pulls himself up the ladder and runs screen left, out of frame, followed by a police officer, and then John (Jimmy Stewart). A panorama shows the chase proceed across the rooftops of buildings with Spanish Mission facades, the police officer periodically firing his pistol. Then cut to a medium shot as we see the pursued individual, having reached the end of the rooftop, confidently leaping to another clay shingled one with a steep slope. He just manages to make it, pull himself up to the flat top of the roof and continue on. Next, the police officer makes the same leap without hesitation and nearly falls, attempts to brace a foot on the roof's gutter but his foot slips out so that his leg hangs over the edge as he finally gets a hold and pulls himself up, just in time for John to make a running leap across the break between the buildings and not find a hold on the roof. Go in for a medium close-up as he slips down and near impossibly grabs the same metal gutter that bends and nearly gives way under his weight. A beautiful shot follows of the police officer turning back toward John as the man pursued runs on. Briefly, instead of focusing on John's drama and the officer, our imaginations follow the fleeing individual who doesn't slow down, who doesn't look back, who we understand will never be identified, the first mystery of the film. Cut to John clinging to the gutter, then his view of the street about five stories below as the music shrieks with the threat of his falling that distance. The police officer carefully lets himself down the roof to reach out to John, calling, "Give me your hand." We understand that not only is John unable to do so, but that if he did manage to give his hand to the officer they would both immediately fall to their deaths. A close-up of the officer shows him reaching lower toward John, again asking for him to give him his hand, but Jimmy dangles over the abyss unable to even yell. A close-up of the officer's hand shows it nearing John, and the confident, strong grasp of the hands of the pursued on the ladder at the opening mark a sharp contrast to John's grasp on life (which is actually pretty good if he survives this and he does). Then the officer slips, and in a medium shot we watch as he tumbles off the roof, over John, to plummet to the ground. John watches as people run to gather around the body of the officer. Fade to black.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Throughout the movie, Stewart will be assailed by guilt over the officer's death, though what happened was no fault of his own. Had he managed to reach up and grab the officer's hand, they both would have fallen to their deaths. The audience knows that the police officer, out of a desperate desire to help, made a bad judgment call in attempting to save Stewart on his own, offering his hand when he himself had nothing onto which to hold.

As the film continues, people wonder, "How does John get down?", for the movie doesn't answer the question, nor does it need to do so, we can easily accept a safe but difficult rescue and move along. But as we don't see the rescue, as we are left with John hanging from that fragile gutter that must cut into his fingers, the longer he waits in our imaginations, when we do reflect upon it, our not ever seeing him rescued, the more is the desire eventually to release, to allow John to let go, weariness calling to give in as the idea of falling becomes increasingly abstract and even tolerable, for one is alive as one is suspended.

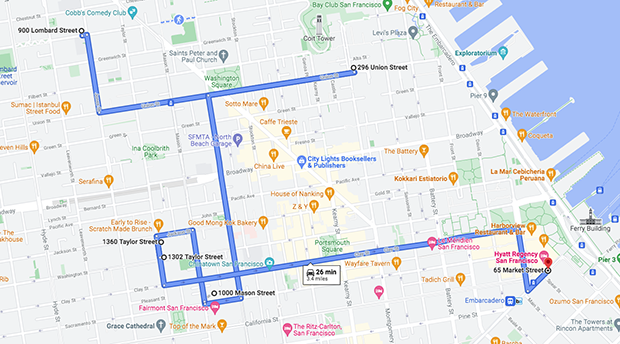

Just where in San Francisco is Stewart's initial confrontation with the abyss? Thanks to ReelSF we know the rooftops span 1302 to 1360 Taylor Street. In the background, through most of the scene, we see the giant neon SP, the Southern Pacific sign, which raised a furor upon its construction, about 1954/55, atop the Southern Pacific building at what was then 65 Market Street. By 1961 it was announced the sign would be removed, so Hitchcock captured what was hated and considered, during its brief existence, a terrible blot on San Francisco's beautiful landscape, and one may wonder if Hitchcock chose, in part, to display it in the film because of the controversy. "God damn, there's that SP sign," you know a number of San Franciscans must have glowered, and just maybe the insult of it featured in Vertigo helped bring it down.

Later we will return to the Southern Pacific by way of my discussing James Leary Flood, who built the Flood Building in which the Southern Pacific was located prior to its move to 65 Market Street in 1917.

The opening panorama, this chase across the rooftops, means we can see from, beyond the ladder that takes us up to the rooftops, the Brocklebank apartments at 1000 Mason Street, where we will learn Madeleine Elster lives, the pursuit broadening the vista all the way over to Coit tower on Telegraph Hill to the north, which is the landmark by which Madeleine will ostensibly remember where John lives and near which Midge resides at 296 Union Street, John instead a number of blocks over at 900 Lombard Street on Russian Hill. (The knowledge of all these locations is thanks to ReelSF! They did a wonderful job finding and collecting them.) This film really is a movie also about San Francisco. Hitchcock filmed on sets and with rear screen projections but he made it so the scenes and homes and shops were almost all tied to real places, and if this rooftop chase, and the confrontation with the abyss happens with Brocklebank apartments in the background, and Coit tower, there's a reason for this. Hitchcock wanted us to see the Brocklebank first, and not know what it was, that this chase that ends in death is in view of where lives another person who John will later believe he was unable to save from plunging to her death because of his vertigo, a woman who becomes his obsession, Madeleine.

The view spanning from Madeleine's (the Brocklebank at 1000 Mason), to Midge's

on Union Street, the Coit Tower (by which Madeleine says she finds John)

and John's place on Russian Hill at 900 Lombard Street

The Brocklebank (screengrab lightened)

The SP sign (screengrab lightened)

Coit Tower (screengrab lightened)

Ostensibly from atop 1360 Taylor Street showing Russian Hill straight ahead

and Coit Tower to the right (screengrab lightened)

After the trauma of James Stewart left to dangle over the infinite abyss of death with no seeming way out of his predicament that doesn't involve for far too long waiting rescue while dependent on the ability of his wearying, numbing fingertips to continue clinging to a disabled, broken gutter that may or may not entirely collapse and is certainly sawing through his flesh, we find ourselves in a sunny San Francisco apartment with a brilliant, enviable view of the city and so much bohemian atmosphere as the stage for an artistic yet professional woman at work. She is not unattractively not a woman who makes her living off her looks, and not a woman who lives well on some invisible source of income such as parental funds, ancestral dollars, or a fantasy film money tree evergreen with cash. Midge is a self-supporting, obviously successful commercial artist, not a woman dependent on her husband in exchange for housekeeping and maternal duties or for looking good while hired help does the labor. Midge works, and she works even as we are introduced to her while John rests on a bentwood lounge chair playing with juggling a cane that he hates, that symbolizes the physical injury by which he has suffered injury also to his manhood rather than enhancement by heroic deeds. Seated lower than Midge, in the lounge chair, feet elevated, though he effects nimble play he is the invalid, but not in the way James Stewart was an invalid in Rear Window. In Rear Window, the invalid was aggressively a photographer who continued to be a photographer, his confidence wasn't impacted, and he had the sophisticated vixen Grace Kelly (since wed in real life to a real-life royal) always eager to nestle into his lap while he a little too voyeuristically spied on his neighbors but also uncovered a murder. John has no Grace Kelly, he instead has friend Midge, who may have a lovely, enviable bohemian-modern apartment with metal-wire modern chairs and a jute rug and bamboo blinds with tassel pulls, and walls filled with commercial and modern fine art, but she isn't Grace Kelly. She is Midge, and the name Midge is but 4 years away from being released to the world as Barbie's cute, freckled, decidedly not sexy friend who maybe gets the leftover men who can't get near Barbie. She has the name of a pestering, flying insect. Midge is the classic 1950s example of "Men don't make passes at girls who wear glasses". Her glossy blond hair will do her no good at winning the lusty hearts of the majority of the male audience, nor will her figure, though it isn't hidden under shapeless clothing as I've read some others accuse. She is attractive but is played, by Barbara Bel Geddes, as a woman who is uninterested, at least with John, in being anything but a person on equal footing with male companions. In another movie she might have sexy friends that teach her to doll up, remove her glasses, and grab attention. This is not the film. But Midge knows all about allure as she illustrates it. We even see propped up in a window an illustration she has done with the title "Allure".

Midge and John are pals. They banter easily and joke with one another. They have obviously a shared history. Despite its feminizing potential, he doesn't mind discussing the corset he's been forced to wear, due his injury, and how it pains him. Enthusiastically, he tells her how the next day the corset comes off and he will be a free man, able to scratch again, and will throw the cane out the window. Stricken by another pain, he asks Midge if she supposes many men wear corsets, and when she replies more than he would imagine he asks how she knows, from personal experience? I'm always surprised how much dialogue there is in this scene, for it is delivered lightly and circles round and around as it makes its way to important points that reveal little-by-little less about the characters than initiating mysteries. Midge redirects the conversation to ask John what he will do now, after the corset comes off, with his quitting the police force rather than becoming the chief of police as he'd once hoped as a brilliant young lawyer. She doesn't accept his excuse of acrophobia getting in his way. She doesn't accept his guilt over the officer's death, assuring him it wasn't his fault. She sees no reason for him to quit. Midge seems to know something else is a problem, besides or aggravating the acrophobia. Does he use the acrophobia as an excuse to quit? Whether or not John belongs in a desk job with the police, as Midge believes he does, we don't know, but John is determined not to consider it. When John says he's just going to not do anything for a while, now a fairly "independent" man, and Midge proposes he go away for a while, he immediately tenses and accuses her of being motherly, of wanting him to go away so he'll forget things and not crack up. He knows Midge is concerned about him--or John is concerned about himself--and now it's his turn to redirect, asking her to take off the classical music she's been playing, which he finds annoying, and inquiring what's the thing she's been drawing. It's a bra, obviously, and as it works on the cantilever principle it not only refers to Howard Hughes and the bra he designed for Jane Russell's appearance in The Outlaw (which she didn't wear) but also anticipates Hitchcock's North by Northwest, a film a couple of years in the future, and the glamorous cantilever house high on Mount Rushmore that so many would believe was real and designed by Frank Lloyd Wright.

Midge has written on her drawing of the absurd bra NTILEVER rather than CANTILEVER. This must, absurdly, be the bra's name, but it looks like Midge, despite her experience, forgot how to judge the space needed for the name and dropped the first two letters, which means she also misjudged in reverse, with the first couple of letters of the name being dropped rather than the last couple. It's bothersome. It's the same kind of annoyance, considering Hitchcock's attention to detail, that I felt with the opening credits when I observed that, likely due hairstyle, part of the woman's ear is notched out in the opening shot, there is a black cut-away where a curl of her hair would have been, clipped out because her hair has been clipped out. Why the hell would you do that, Hitchcock, and not just have her hair pulled behind her ears? Then I remember that in Howard Hughes' The Outlaw, Doc Holliday, in an attempt to instigate a gunfight, nicks both of Billy the Kid's ears. And Billy the Kid doesn't even flinch. It's a bizarre scene that caps other scenes in which one wonders whether Jane Russell is the real love interest or is the real love interest between Billy the Kid and Doc, and then Billy and Doc make up when Billy says Doc is the only real partner he's ever had in life. That's not going to have anything to do with the opening of Vertigo but it's fun so I'll leave it in here.

John has already brought up Midge's love life (how does she know men wear corsets) and despite her evasion he pursues the subject again, this time directly, then even inquires if she's ever going to get married. We realize how fully loaded a question this is when Midge says there's only one man for her, and he accepts that she is referring to him, they having been engaged for three weeks in college. Hitchcock goes in twice for an extreme close-up on Midge as they talk, and Johnny reminds how she called the engagement off then says he's still available. Her expression is inscrutable, self-contained, discreet, unavailable to Johnny who shows no understanding at all how sensitive this subject is to her. There are numerous mysteries there—why Midge broke off the engagement when she loved him, which she did as she still carries a torch for him, why is he still available, and why does he seem so clueless to her feelings despite their friendship and having remained this intimate for this long.

College days. John asks if she remembers Gavin Elster, which she doesn't.

There's no getting around this, that Jimmy Stewart was born in 1908 and Barbara Bel Geddes in 1922. It's one thing for Stewart to be paired with Novak, which I'll discuss later, but John and Midge are supposed to have been in college together and she's fourteen years younger than him. And then Tom Helmore, playing Gavin Elster, is supposed to be their age, whatever age that is, and was born in 1904. Kim Novak's youth we can deal with, and I later will, but it's impossible to close the gap between Geddes and Stewart. The gap between Helmore and Stewart is manageable, but not the gap between Geddes and Stewart and Helmore. Hitchcock could have easily avoided the issue by leaving out any reference to college.

|

|

|

|

John decides he will meet with Gavin the next day (no doubt wanting to get out of the corset first, to not feel constrained and feminized), and is about to leave when he asks why Midge had said his acrophobia can't be lost. She reveals, unhesitatingly, she'd discussed it with her doctor and he said only another great emotional shock could counter it, and probably not. John replies that he thinks he can deal with it by what would be desensitization, introducing himself slowly to heights. When he enthusiastically demonstrates by climbing on a short stool, Midge, circumspect, gets a three-step stool from the kitchen. John, upon reaching the third step, inadvertently looks out the window and sees about a five story drop. He panics, his vertigo kicks in, and he completely succumbs, dropping into a near faint, his head slung back, Midge catching him as he falls.

|

|

|

|

We have wondered why Midge broke off with John. The way John describes himself as available, I'm reminded of how Jimmy Stewart remained a bachelor for so long that he became dubbed "The Great American Bachelor" in his forties, and how when he proposed to Olivia de Havilland she turned him down as she felt he wasn't yet ready to settle down. Has this been scripted with Jimmy Stewart's history partly in mind? But we have also John bristling when he believes Midge is acting motherly, attacking her suggestion that he get away, asserting she believes he might crack up, and the scene ends with this tremendous vulnerability, John collapsing into Midge's arms and clinging to her. Hitchcock would have us think that he clings to her much like a child.

John is a very fragile individual and because of their conversation one wonders if he has some history that would reveal this fragility is more complex than PTSD from his accident and the death of the other officer.

John (grabbing his side as he plays with the cane): Ouch!

Midge: I thought you said no more aches or pains.

John: It's this darned corset. It binds.

Midge: No three-way stretch? How very un-chic.

John: You know the police department doctors. No sense of style. Anyway, tomorrow will be the day.

Midge: What's tomorrow?

John:

The corset comes off tomorrow. I'll be able to scratch myself like anybody else tomorrow. I'll throw this miserable thing out the window. Be a free...(suffering another pain)...I'll be a free man. Midge, do you suppose many men wear corsets?

Midge: Mmm. More than you think.

John: Really? What? Do you know that from personal experience or...

Midge:

Please. What happens after tomorrow?

John: What do you mean?

Midge:

What are you going to do once you've quit the police force?

John:

You sound so disapproving, Midge.

Midge: No. It's your life. You were the bright, young lawyer who decided he was going to be chief of police someday.

John: I had to quit.

Midge: Why?

John:

Because of this fear of heights I have, this acrophobia. I wake up at night seeing that man fall from the roof, and I try to reach out to him and it...

Midge: It wasn't your fault.

John: I know. That's what everybody tells me.

Midge: Johnny, the doctors explained to you...

John: I know, I know. I have acrophobia, which gives me vertigo, and I get dizzy. Boy, what a moment to find out I had it.

Midge: You've got it, and there's no losing it, and there's no one to blame. So, why quit?

John: You mean, and sit behind a desk, chairborne?

Midge: Where you belong.

John: What about my acrophobia? What if I...suppose I'm sitting in this chair, behind a desk. A pencil falls from the desk down to the floor and I reach down to pick it up...bingo, my acrophobia's back.

Midge: Oh, Johnny-O. What'll you do?

John:Well, I'm not gonna do anything for a while. Don't forget, I'm a man of independent means, as the saying goes.

Fairly independent.

Midge: Well, why don't you go away for a while?

John: You mean, to forget? Midge, don't be so motherly. I'm not gonna crack up.

Midge: Have you had any dizzy spells this week?

John: I'm having one right now. Midge, the music. Don't you think it's sort of, uhm...

What's this doohickey?

Midge: It's a brassiere. You know about those things. You're a big boy now.

John: I've never run across one like that.

Midge: It's brand new. Revolutionary uplift. No shoulder straps, no back straps, but does everything a brassiere should do. Works on the principle of the cantilever bridge.

John: It does?

Midge: An aircraft engineer down the peninsula designed it. He worked it out in his spare time.

John: Kind of a hobby. A do-it-yourself type of thing. How's your love life, Midge?

Midge: That's following a train of thought.

John: Well?

Midge: Normal.

John: Aren't you ever gonna get married?

Midge: You know there's only one man in the world for me, Johnny-O.

John: You mean me. Well, we were engaged once though, weren't we?

Midge: Three whole weeks.

John: Good old college days. But you were the one that called off the engagement, you remember? I'm still available. Available Ferguson. Oh, Midge, do you remember a fellow in college by the name of Gavin Elster?

Midge: Gavin Elster?

John: Yes, funny name.

Midge: You think I would. No.

John: I got a call from Gavin today. It's funny, he dropped out of sight during the war. Somebody said he went East. I guess he's back. It's a Mission number.

Midge: That's Skid Row, isn't it?

John: Could be.

Midge: He's probably on the bum and wants to touch you for the price of a drink.

John:

Well, I'm on the bum. I'll buy him a couple drinks and tell him my troubles.

But not tonight. How about you and me going out for a beer?

Midge: Uh-hum. Sorry, old man. Work.

John: Then, I think I'll go home. Midge, what did you mean, there's no losing it?

Midge: What?

John: The acrophobia.

Midge: I asked my doctor. He said that only another emotional shock could do it and probably wouldn't.

You're not going to go diving off another rooftop to find out?

John: I think I can lick it.

Midge: Well, how?

John: I have a theory. I think if I can get used to heights just a little bit at a time, just a little, like that, progressively, you see? I'll show you what I mean. Here. I'll show you what I mean.

We'll start with this.(He pulls out a short stool.)

Midge: That?

John:

What do you want me to start with, the Golden Gate Bridge?

Watch this. Here we go. (Climbs up on the stool.)

There.

Now, I look up, I look down.

Midge: You're kidding. Wait a minute.

John: There's nothing to it. There's nothing to it.

Midge (brings him a higher step-stool chair): Here.

John: Oh, that's a girl. I'll use that. Put it right there. All right, here's the first step.

Midge: Okay, now step number two.

John: Step number two coming up. There. See? I look up, I look down, I look up...I'm going right out and buying myself a nice tall stepladder.

Midge: Take it easy now.

John: All right, now here we go. No problem. Yeah. Why, this is a cinch. Here, I look up, I look down. I look up, I look down. (Looking down he sees the view out the window and that it's several stories to the street. He begins to faint.)

Midge (catching him, he clinging to her): Oh, Johnny, Johnny.

First the Hitchcock cameo. He strides past the gate to the shipbuilding company where we will find Gavin is a big boss, not on skid row. Hitchcock and John pass one another, John just arriving and stopping at the gate to ask directions.

Look at this design for a wealthy shipbuilder's office that Hitchcock would later use as his own office, for Hitchcock was a wealthy and powerful man in his own right and had 200 acres worth of ranch in California and an estimated inflation-adjusted net worth of $200 million at the time of his death in 1980. Look at those richly wood-paneled walls that bear no resemblance to mid-twentieth century American suburban colonial sympathies and all their faux pine paneled basements and family rooms and kitchens. Look at those leather chairs with their brass buttons. Look at Elster's desk which is near the size of a bed and lavishly decorated with fine wood carving. Look at all those great cranes outside the picture window through which Gavin may gaze upon big business going about its big business. Look at all those paintings and prints on the walls, finely matted and framed (that alone costs a mint), including George H. Burgess' painting of Telegraph Hill, "San Francisco in 1849", a pictorial record of San Francisco and the shipbuilding company Gavin Elster heads up there, seeing to his wife's interests, her family gone now and her father's partner holding down the office in Baltimore. Midge, who hadn't remembered Elster, had wondered, because of the Mission number, if Gavin was a bum wanting to tap John for a drink, when instead Gavin is an incredibly wealthy man, but it is his wife's business and money that he manages and he isn't particularly happy with the job, finding it incredibly dull.

Elster doesn't tell John he has a beautiful wife he wants him to follow. He tells John he has a wife who has been possessed by her great-grandmother that he wants John to follow and assures John that he and his wife are happily married so she is certainly not having an affair. You must do this as my friend or get out of my office because you're otherwise of no use to me, Elster pretty much says, and John sticks around rather than walking out, and when he proposes that Elster use some private investigators he knows and Elster refuses he says he doesn't want to get mixed up in it but he's not going to turn down Elster's invitation for John to quietly surveil Madeleine at Ernie's that night before she and Elster go to the opera. Ernie's is, after all, a nice restaurant. Hitchcock's favorite in San Francisco. He loved Ernie's.

There not being any Midge in the book, D'Entre Les Morts by Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac, the novel opens with Paul Gévigne (Elster), a man who says he was too busy to call ahead and make an appointment with Roger Flavières (John), suddenly dropping by the latter's apartment on the spur of the moment. They haven't seen each other in fifteen years, since their days at the Faculte de Droit, and yet there Gévigne sits, redolent with a near overwhelming atmosphere of wealth that Roger learns comes of Paul's fortunate marriage to the daughter of an industrialist, both of her parents now deceased. This friend who Flavières hasn't seen in fifteen years tells him about how his wife, Madeleine, to whom he has been happily married for four years, now sometimes becomes another woman, and he is convinced she may be possessed by her great-grandmother, Pauline Lagerlac, who was a bit weird, experienced poltergeists when she became an adolescent, was perhaps even a little mad, wanted to become a nun but gave that up, married, had a son, her moodiness wasn't stabilized by motherhood as everyone had hoped, and killed herself several months later at the age of twenty-five. Madeleine is now twenty-five and in the grips of curious trances and moods she disappears and seems to not recollect anything about what happens during these states and may not even be aware of them. After fifteen years, here is Gévigne, wanting Flavières to follow his wife, see what she does, make sure she's okay. Also, he knows about Roger's accident and was sorry to hear of it.

What was Roger's accident? Much as in the movie. On the way to explaining the event, Roger relates how he should never have become a detective, he didn't like it but his father was a divisional inspector and he was pushed into it, there was nothing else for him to do. The individual he and his colleague were sent to arrest wasn't even dangerous. The man fled to the roof to hide behind a chimney. Roger, on the high, sloping roof, was stalled by his fear of heights, so the officer with him pursued and fell to his death. Yes, Paul remembers Roger had a fear of heights. Paul also remarks on how Roger used to be interested in psychology, which was why he thought Roger might be the person to help him with this mystery concerning Madeleine. Paul has also turned to Roger because he considers him one of his oldest friends.

Roger decides to help Paul out, considering that he will be doing his old friend a favor, and he says he feels that he and Madeleine have something in common. The reader might wonder what that could be. Roger believes Madeleine is hiding something, and from the beginning he actually dislikes Paul intensely, his smugness, the confidence that wealth has supplied him, the fact Paul will profit off the war, and feels the stout fellow deserves it if his wife is involved with another and fooling her husband with these attacks, her amnesia a smokescreen.

And just what is it about Roger that causes Paul to determine he is an easier mark?

The book is more complex than the film, and very different after a point. The story of Paul and Roger and Madeleine begins just prior Germany's invasion of France in May of 1940. Before the invasion, the future is uncertain, no one knowing what is going to happen, waiting, people even wanting the war to start in earnest so the suspense of the waiting will be over. Life is in such crisis that after Madeleine's death, coincident with Germany's invasion, Roger will be surprised the police pay attention to it at all. Due the invasion, Roger flees south, not realizing he won't return for years. The second part ot the book opens with the war over and Roger returning home. Inbetween is chaos. Before was the purgatorial drift into chaos. After, amidst the elation of the occupation ending, is the chaos that comes with its end and the confrontation as well with all that has been lost. Hitchcock replaces the loss that comes with war with both Gavin and John, natives of San Francisco, disquieted by the changes that remove the city further and further from its old days, or at least Gavin professes to be unsettled by the loss of wild, old San Francisco--the power, the freedom, the color, the excitement--and perhaps would provoke similar misgivings in John.

Rather than clinging to the past, at film's end, what John will protest to Judy, as he drags her to the bell tower, is that he has one more thing to do in order to free himself of the past.

What the book invites the reader to consider from the beginning, which the movie might not, is why Elster has sought out John, a person he's not had contact with in many years, who he calls "Scottie", which we are to later learn means Elster was an acquaintance rather than a close friend. Or it may be that the movie audience does think of this, but the rules that demand a novel fiction have perhaps some degree of feasibility are less so with movies, critical observers often chastised by the viewing public who expect less from a plot, expect errors, yet rebel against the idea a filmmaker might also use this looseness, this slippery commutability as a thing particular and peculiar to the medium of film as art.

John: How did you get in the shipbuilding business, Gavin?

Elster: I married into it.

John: Very interesting business.

Elster: No, to be honest, I find it dull.

John: You don't have to do it for a living.

Elster: No, but one assumes responsibilities.

My wife's family is all gone.

Someone has to look after her interests.

Her father's partner runs the company yard in the East. Baltimore.

So I decided, as long as I had to work at it, I'd come back here. I've always liked it here.

John: How long have you been back?

Elster: Almost a year.

John: You like it?

Elster: Well, San Francisco's changed.

The things that spell San Francisco to me are disappearing fast.

John: Like all these.

Elster: Yes, I should have liked to have lived here then. Color, excitement, power, freedom.

Shouldn't you be sitting down?

John: No, no, I'm all right.

Elster: I was sorry to read about that thing in the paper. And you've quit the force.

Is it a permanent physical disability?

John: No, no.

It just means that I can't climb stairs that are too steep or go to high places, like the bar at the Top of the Mark, but there are plenty of street-level bars in this town.

Elster: Would you like a drink now?

John: No, I don't think so.

No, it's a little early in the day for me.

Well, I guess that just about covers everything, doesn't it?

I never married, I don't see much of the old college gang.

I'm a retired detective and you're in the shipbuilding business.

Now, what's on your mind, Gavin?

Elster: I asked you to come up here, Scottie, knowing that you'd quit detective work, but I wondered whether you'd go back on the job as a special favor to me.

I want you to follow my wife.

No, it's not that. We're very happily married.

John: Well, then...

Elster: I'm afraid some harm may come to her.

John: From whom?

Elster: Someone dead.

Scottie, do you believe that someone out of the past, someone dead, can enter and take possession of a living being?

John: No.

Elster: If I told you that I believe this has happened to my wife, what would you say?

John: Well, I'd say take her to the nearest psychiatrist, or psychologist, or neurologist, or psycho...or maybe just the plain family doctor.

I'd have him check on you, too.

Elster: Then you're of no use to me. I'm sorry I wasted your time.

Thanks for coming in, Scottie.

John: Okay.

I didn't mean to be that rough.

Elster: No, it sounds idiotic, I know.

And you're still the hardheaded Scot, aren't you?

Always were. Do you think I'm making it up?

John: No.

Elster: I'm not making it up. I wouldn't know how.

She'll be talking to me about something.

Suddenly the words fade into silence.

A cloud comes into her eyes and they go blank.

She's somewhere else, away from me, someone I don't know.

I call to her, she doesn't even hear me.

Then, with a long sigh, she's back.

Looks at me brightly. Doesn't even know she's been away.

Can't tell me where or when.

John: How often does this happen?

Elster: More and more in the past few weeks.

And she wanders. God knows where she wanders.

I followed her one day, watched her coming out of the apartment, someone I didn't know.

She even walked a different way.

Got into her car and drove out to Golden Gate Park, five miles.

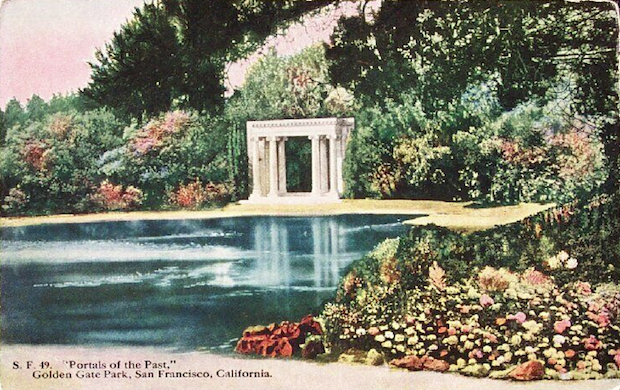

Sat by the lake, staring across the water at the pillars that stand on the far shore.

You know, Portals of the Past.

Sat there a long time without moving.

I had to leave, get back to the office.

When I got home that evening, I asked her what she'd done all day.

She said she'd driven out to Golden Gate Park and sat by the lake, that's all.

John: Well?

Elster: The speedometer on her car showed that she'd driven 94 miles. Where did she go?

I've got to know, Scottie, where she goes and what she does, before I get involved with doctors.

John: Have you talked to the doctors at all about this?

Elster: Yes, but carefully.

I want to know more before committing her to that kind of care.

John: Alright, I'll get you a firm of private eyes to follow her for you.

They're dependable, good boys.

Elster: I want you.

John: Look, this isn't my line.

Elster: Scottie, I need a friend, someone I can trust.

I'm in a panic about this.

John: I'm supposed to be retired. I don't want to get mixed up in this darn thing.

Elster: Look, we're going to an opening at the opera tonight.

We're dining at Ernie's first. You can see her there.

John:

Ernie's.

Before taking up this analysis in earnest, which I'd started and stopped a couple times over a few years, I saw where Brandon Freels had made a website post about how Gavin Elster tells Scottie his wife sometimes visits the Golden Gate Park lake to gaze across at the pillars of Portals of the Past on the opposite shore, but the landmark was never shown in the movie.

I'd previously overlooked this bit, the Portals of the Past, and it caught my attention and got me thinking again about the film and motivated me to work on the analysis again.

Considering Hitchcock, that this place was mentioned yet not shown in the film seemed to merit taking a look at it. The painting of Carlotta, that Madeleine visits at the Legion of Honor, has Carlotta leaning back against a pillar. Never mind that Carlotta died in 1857 and that the pillars of Portals of the Past date to 1891—I at first still wondered, as they were both by lakes, if the pilliar in the painting might be similar to those of the pillars of Portals of the Past? As it turns out, the pillars are different. In the Carlotta painting, the pillar before which she stands is on a much taller pedestal.

With its mention, if our attention isn't being necessarily drawn to the Portals of the Past monument itself, then what else might we consider other than the Portals of the Past being only a reference to the past? I felt like Portals of the Past would teach me something about if I sought it out and what might that be?

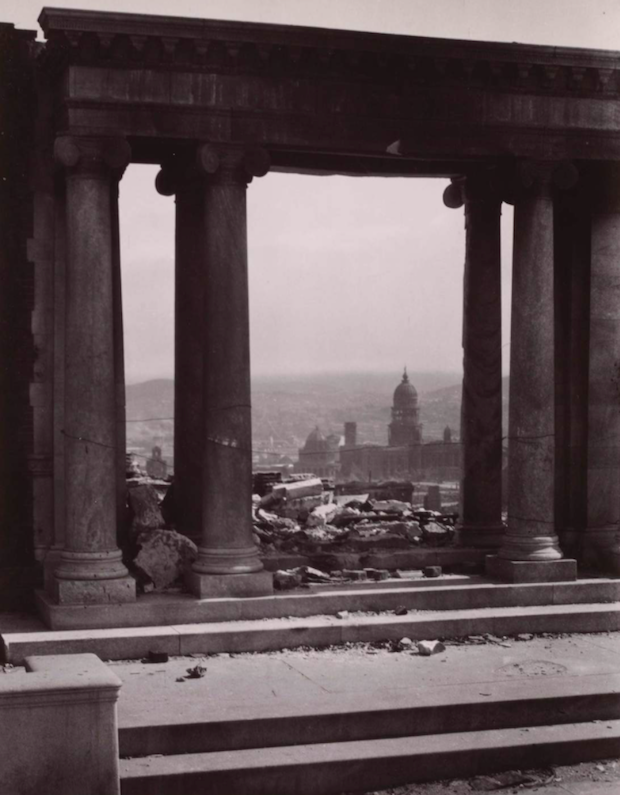

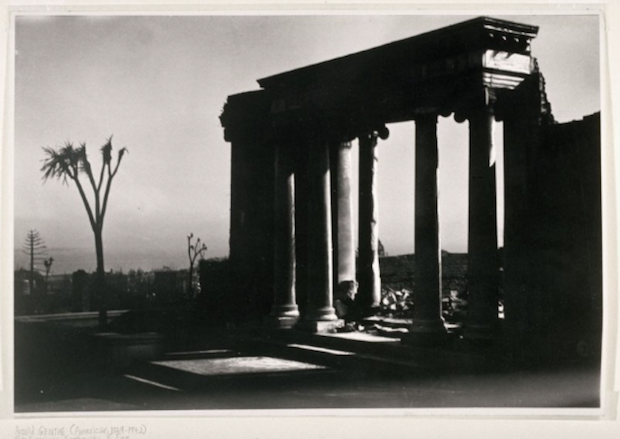

Arnold Genthe photo of the ruins of A. N. Towne's home

Arnold Genthe photo of the ruins of A. N. Towne's home

Arnold Genthe photo of the ruins of A. N. Towne's home

Arnold Genthe photo of the ruins of A. N. Towne's home

Portals of the Past once was the porch entry to a mansion belonging to railroad tycoon, Alban Nelson Towne. Located at 1101 California Street and Taylor Street (southwest corner), the mansion was devastated by the fires of the great earthquake of 1906. The remains were photographed, by Arnold Genthe, as a doorway through which to view the devastation, most notably of the dome of City Hall, and later salvaged and relocated to the park. Those photos serving for inspiration, Charles Rollo Peters, once a famed San Francisco artist, did a dark and moody painting of the scene that hung for many years in the famed Bohemian Club. Though it's written that these images became an "emblem of the loss of an era", they were also intended to redirect to the future. "This is the portal of the past—from now on, once more forward," seems a quote associated with them, that I have seen online and also find it remembered in a 1969 San Francisco Examiner article.

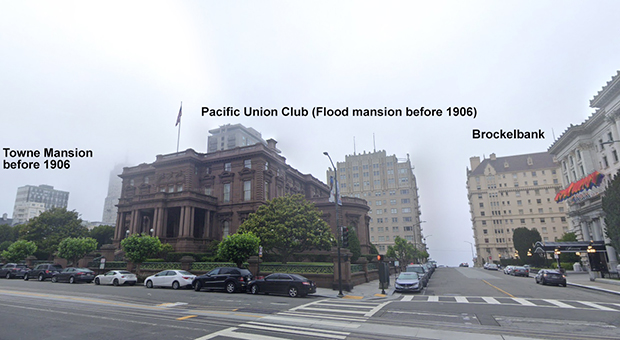

For context, below we see the A. N. Towne mansion and that it was located on a corner opposite what would become the Pacific Union Club which will be discussed in depth in Part Two as it also served as a basis for a location and has history that appears to connect with the film. The next image shows approximately where the Towne home once was and its relationship to the Brockelbank. The next image down is the monument's location at Golden Gate Park, and then the painting that was at the Bohemian Club.

A. N. Towne's home location across from the Flood Mansion which would become the Pacific Union Club

A. N. Towne's home location across from the Flood Mansion which would become the Pacific Union Club

A. N. Towne's home approximate location (Portals of the Past Origin), southwest corner of California and Taylor Streets, relative to Pacific Union Club (Flood Mansion) and the Brocklebank

A. N. Towne's home approximate location (Portals of the Past Origin), southwest corner of California and Taylor Streets, relative to Pacific Union Club (Flood Mansion) and the Brocklebank

Portals of the Past at Golden Gate Park

Portals of the Past at Golden Gate Park

Charles Rollo Peters' Portals of the Past

Charles Rollo Peters' Portals of the Past

Elster's office is covered with old paintings and prints depicting San Francisco of the 19th century, and Elster remarks as to that city disappearing. The restaurant highlighted in the film, Ernie's, is styled after an old bordello and was once a link back to the Barbary Coast red light district, its location being what had once been the Frisco Dance Hall (which may tie in with Carlotta having once been a dance hall girl). When John is trying to learn about Carlotta and the San Francisco of her era, Midge directs him to a bookshop owner who can tell him about the time of the "bohemians".

The Charles Rollo Peter's painting of the Portals of the Past had hung in the famed Bohemian Club for decades.

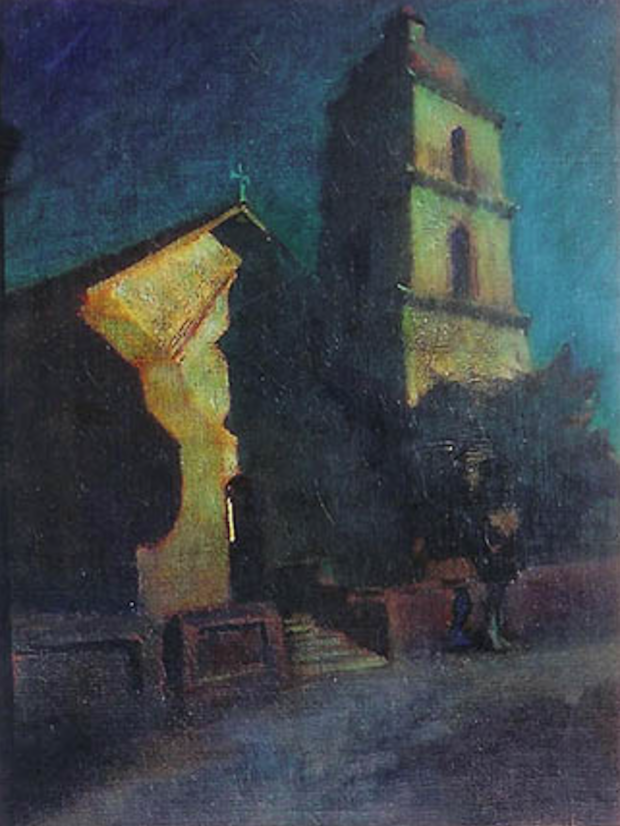

Charles Rollo Peters was known as a painter of nocturnes, often enough solitary buildings shrouded by night and a portion of facade reflecting moonlight so it gleams in the dark. What am I reminded of when I examine his work? The matte painting of the Mission San Juan Bautista in Vertigo. When Scottie returns with Judy/Madeline to the scene of the crime, the setting is that of one of Charles Rollo Peters' nocturnes.

Charles Rollo Peters painting

Charles Rollo Peters painting

Charles Rollo Peters painting Mission Bonaventura

Charles Rollo Peters painting Mission Bonaventura

Charles Rollo Peters' painting

Charles Rollo Peters' painting

Mission San Juan Bautista, imagined as a nocturne for"Vertigo" with a several story bell tower

Mission San Juan Bautista, imagined as a nocturne for"Vertigo" with a several story bell tower

Vertigo is, often enough, a dark film tonally. Hitchcock seems to want to give us the feeling of how quickly light can vanish in San Francisco with all its hills, and I've earlier noted how this will relate to Wagner's treatment of light and dark in his Tristan and Isolde, the reason and rationality of light being the enemy of the mystical realms of the night and death. When Midge and Scottie are at the bookshop and he is being told the story of Carlotta, the interior rapidly and noticeably darkens as Carlotta's suicide is related. When they exit, it is now dark enough that the interior lights of the shop are cut on.

Might Hitchcock have once planned to film Portals of the Past? Shooting took place from September to December 1957. Earlier in the year, on March 22, another earthquake this time damaged the Portals monument, so that a square wood post took the place of the eastern back inner column until 2009 when it was replaced. However, that the San Juan Bautista Mission didn't have a tall bell tower didn't stop Hitchcock from filming it. He simply replaced it in the matte painting. It may be that Hitchcock preferred to only mention Portals of the Past and allow the majority of the viewing audience to simply imagine it--perhaps as even being like the lake and pillar in the painting of Carlotta.

Interestingly, though Carlotta died in 1857—we are shown her headstone twice so we may be confident of this—Hitchcock disrupts the fantasy window on Carlotta's past by having Madeline take a room in what was supposed to be a house built for her great-grandmother, which had become the McKittrick Hotel, but that Victorian building wasn't constructed until 1888 and its design distances it from Carlotta. I will propose later why this may be so, the film blending the fiction of Carlotta with a real life story that occurred later.

Take note of the dead tree in the foreground of the matte painting of San Juan Bautista. If we return to Midge's apartment with its glorious view of San Francisco, next a table beside the entry foyer is a black silhouette that resembles this tree, standing on the floor, two of its branches draped with scarves.

Open with an establishing exterior shot for the five-star restaurant, Ernie's, its doors with the stained glass windows, stated to be a favorite restaurant of Hitchcock's. Crossfade to John seated at the restaurant's bar, its lobby beyond. The camera pulls back and dollies around to reveal a neighboring dining room of the restaurant that is packed with elegant and monied diners, the women in substantial finery, not a young crowd, and of course we must notice an obviously younger woman, a very sensual expanse of her nude back turned to us, framed less by the black straps of her gown than a voluminous emerald green and black satin wrap that she has worn to her table rather than surrendering at the coat check. Almost all that we will know about this dress is for the flesh it reveals, and the stole that conceals the gown, that vibrant near neon green of which halts the eye and redirects it back up to the flesh of the woman's back and her up-pinned hair that is so blonde it is nearly pearl-gray white in some lights. Of course this is Madeline, the only woman in the room in emerald green, the only woman in the room with a back so broadly exposed, the only woman in the room that design and the camera conspire to grab and hold our attention. The mysterious Madeleine who dines with her husband before visiting the opera, perhaps many of the women in the restaurant also gowned for the opera.

Vertigo is also a travelogue of San Francisco, its scenery and chaotic gold-chasing history as much the star as Jimmy Stewart and Kim Novak. It is 1958. Have you heard of Ernie's and never been there? Here it is. Have you never heard of Ernie's and never have a hope of being there as you don't have the cash or credit or the social registry to get a reservation within the next six months? Here is Ernie's, and it is rich and plush, but Ernie's is also bordello gaudy with the red brocade fabric that relentlessly covers its walls, the brocade serving as backdrop to such decorations as framed antique fans that might have fluttered before the faces of 1850s San Francisco women, such a fan positioned over a fireplace mantle and wreathed by examples of porcelain plates hand-painted with flowers. There are also framed paintings of flowers embraced by grand flower arrangements that, if real, must be delivered daily to ensure freshness, for flowers die quickly. The lights on the walls and the chandeliers are old Victorian style, dangling crystals, and the table lamps have hurricane shades that are cranberry or ruby red cut glass. The ambiance that is Ernie's decidedly wants us to feel something of the thrilling history of old San Francisco.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Elster and Madeleine rise to leave. From John's point of view at the bar, as Madeleine approaches us, we should notice on the wall facing John, between the twin doorways to the dining room neighboring the bar, a framed print that is a tabula scalata, which is a double image, a "ladder" (to scale, to climb) picture. The image is composed of alternating strips so that when viewed from one direction it presents one aspect but another when viewed from the other direction. This print is a vertical tabula scalata, and it's impossible for me to say what it is, but the asubject is probably not important whereas the type of print is. We should think of it when Madeleine stops and stands beside John, her profile facing screen right, then she turns and her profile faces screen left. We should again think of it when Madeleine passes out of the entry of the restaurant, exiting by the full-length mirror with its elaborate gold frame, so we see her from the rear and from the front.

Further, the view of Madeleine and Gavin exiting the restaurant gives the appearance of the different perspectives of a cubist work due the doorways and a peculiar flatness of depth of field.

As Madeleine exits, we viewing her from the back, her train gives the appearance of her more floating than walking. One may be reminded of a scene in which Belle floats down a hall in Cocteau's Beauty and the Beast, which I mention now as I will be referring to another Cocteau film in Part Five.

Below is a tabula scalata from Wikipedia showing death hidden within a woman's portrait. I will later compare this folding to a switchback, and we should be reminded of how when the name "Kim Novak" appears in the credits it's when the woman darts her eyes right and left.

In the book, Roger (John) does not first see Madeleine at a restaurant but at the opera. As he surreptitiously observes her, drawn to her as John is at Ernie's, he jealously imagines the life her husband has with her, and himself in her husband's place, taking her to a restaurant and then home and to bed, but he becomes uncomfortable when he imagines interacting with a head waiter. Paul and Madeleine have wealth. Roger, at every moment, is too aware of how distant he is from that world, which means that even thoughts of dealing with servants to the upper class cause him to feel ashamed. Servants to the upper class will know immediately what he is not.

But Roger also considers how death makes everyone the same, and those things that provide stature, assurance, and confidence in life are but props to alleviate the horror of the unknown:

If he had chosen the lawyer's profession, it was to discover the secrets that prevent people living. Even Gévigne, with his money, his factories, his influential friends, wasn't really living. They were liars, all of them, these people who, like Marco, pretended they could ride rough-shod over every obstacle. Who knew whether Marco wasn't at that moment in desperate need of a friend to lean on? A man on the stage kissed a girl...it looked so easy, but that was a lie too. Gévigne kissed Madeleine, yet she remained a stranger to him...The truth was that they were all like him, Flavières, trembling on the edge of a slope at the bottom of which was the abyss. They laughed, they made love, but they were afraid. What would become of them if there weren't whole professions whose job it was to prop them up—the priest's, the doctor's, the lawyer's? The curtain fell, then rose again. The lights shed a harsh glare which made all the faces look a little gray. People stood up so as to have elbow-room for clapping. Madeleine fanned herself slowly with her programme, while her husband bent over to say something into her ear. Another well-known picture—La Femme à L'Eventail. Or was it the portrait of Pauline Lagerlac?

If I think to compare Jean Metzinger's La Femme à L'Eventail with the tabula scalata it is because the woman holds a fan in the painting, a fan is prominently displayed as a piece of art at Ernie's, and later we will see a fan at Judy's. In the painting's cubism we can see a similarity of its corrugations, its broken and varied perspectives, to a tabula scalata that offers an alternate double image by way of its corrugations. We realize the fan also is corrugated, which means that the tabula scalata in the bar area, which we don't see until Madeleine and Gavin are leaving the restaurant, is preceded and anticipated by the framed fan above the mantlepiece. It may be because of the corrugated nature of the fan that the woman holds one in this cubist work that is mentioned in the book upon which the film is based.

Who is Pauline Lagerlac to Roger, really? And who is Madeleine?

Will John take on the job of following Madeleine, who is happily married to Elster and not having an affair? Of course. How could he not?

December 2021. Approx 9600 words (including film dialogue) or 19 single-spaced pages.