Vertigo TOC | Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Films Home

LINKS TO SECTIONS OF THE ANALYSIS ON THIS PAGE:

That's Carlotta

The Gray Suit

Carlotta's Gown

You Mean the Gay Bohemian Days

The Second Meeting with Gavin Elster

The mystery of Constance Flood Stearn Gavin, a review of the early 20th century paternity trial concerning the daughter of a dance hall girl and the wealthy James Leary Flood that was still famous in San Francisco when Vertigo was filmed

Rescued from the Bay

We've been to Midge's but we have yet to visit John's home, instead we get John's home on the road, he in his car preparing to follow Madeleine, parked by the rear of the Pacific Union Club, beyond and opposite the Brocklebank Apartments at 1000 Mason Street where Madeleine lives. (For a thorough guide to locations, visit Reel SF which has done a great job pinning them down and also is able to show the streets John drives.) We know how John dresses, in suits and fedoras, and now we see the car that he "wears", a De Soto Firedome Sportsman, the advertising for which ranged from an ad of a man in denim togs, cowboy hat, leaning on the car parked in the countryside, mountains beyond, smooth performance on bumpy surfaces and a great open road experience promised, to the glamor of several women in long gowns accompanying a tuxedo-attired gentleman whose car will ferry one or all of them? The De Soto Firedome Sportsman was offered in a wide range of colors but Hitchcock's John has chosen an inconspicuous white-on-white.

We have already been acquainted with the Brocklebank Apartments without realizing it, in the scene of the chase across the rooftops and the traumatic fall of the police officer. The night vista reached from the Brocklebank to Coit Tower (and even to Russian Hill), the Brocklebank behind the pursued, the officer, and John as they climbed the ladder onto the roof.

Madeleine is not a woman who opts to hide her wealth. Carrying a dark brown sable fur stole, she's sure to be noticed when on foot. Driving an emerald green Jaguar Mark VIII, heads will snap her direction on the road. It's not going to be hard for John to locate Madeleine in a crowd.

He follows her first to an alley off Grant Avenue, where he watches her exit her car and enter a dingy alley door. We enter through the same door into a dark brick room where John seems to worry he's tracked Madeleine to a film noir rendez-vous. Then he opens another door a crack, through which he imagines she passed, and instead of monochrome lust and murder there's paradise. The first time one watches the film, this shift is more startling than when Dorothy leaves Kansas by tornado and opens her front door to the colorful land of Oz. One's breath is fairly taken away, for through the door's crack is viewed Madeline surrounded by a veritable explosion of color, the Podesta Baldocchi flower store briefly confused with the Garden of Eden. The green we will later associate with the neon light out of which Judy emerges as the resurrected Madeleine is anticipated in the green of the flower shop's green boxes.

|

|

|

|

|

|

And we watch John spying on Madeleine, as Jimmy Stewart had examined his neighborhood from his apartment in Rear Window, but in this film, however Madeleine and Elster's conspiratorial seduction of John, he allows himself to become less an observer than a voyeur, then less a voyeur than a predator.

Having picked up a hand bouquet of small pink roses, Madeleine then heads to the Mission Dolores (San Francisco de Asis) which is the oldest structure in San Francisco, built in 1776. John follows her into the dim church, brightened with gold iconography on the sanctuary wall, and as he enters she is already on the far end slipping out a door to the right. John follows through that door into yet another garden, this one a cemetery. A fog filter softens the scene with hazy, radiant light. In the book as well, Roger follows Madeleine to a cemetery where she ponders a grave, and John, just as with Roger, finds it's the grave of her great-grandmother. For a moment, John is at risk of being noticed by her when she pauses in a walkway not far from him, he not having had the opportunity to fully hide himself. As at Ernie's, near as close to her as at Ernie's, he watches her profile, which communicates innocence, the pink roses abetting, then she turns and walks away.

The perfection of her stillnesses, her poses, her poise, is such that she might be the subject of a portrait, and in the book, as Roger watches her, he is continually reminded of portraiture.

|

|

|

|

|

|

To return to how they enter the cemetery garden. Where John follows Madeleine into the church, to the left of the main entry, I see in Google Maps that there is a door that leads out of that area directly into the cemetery. The longer route, through the sanctuary, is illogical, but that way we are given a look at the sanctuary that will conjure a sense of deja vu when John follows Madeleine into the San Juan Bautista church. So, he follows her into the church body and the door through which she exits is in the sanctuary altar area, beyond the communion rail. That's like stepping onto especially hallowed ground, really bad etiquette to go back there. Plus, as far as I can tell, the door through which she's gone likely has taken her into the sacristy where one prepares for mass. Even if not, and regardless, they exit the church on the right side of it, and must go around the back of the church and to the left to get to the cemetery which is on the left side of the church.

Below, on Google Maps, is where John enters cemetery from behind the church via a gate by a monument that is also viewed in the film. One can see to the right in that Google Map image, up toward the front of the cemetery where there is a door that opens onto the cemetery from what is now the gift shop. That is the section of the church they had appeared to enter from the street, but had not exited directly into the cemetery through that door, instead traveling through the church body.

Below is approximately where Madeleine stands when John examines her profile.

Indeed, when Madeleine leaves the cemetery, she goes toward that white wall in the above Google Maps image, which is the left side of the church, cuts to the right and exits through what is now that gift shop door, rather than retrace her steps to the rear of the cemetery and through the church.

John, as he watches Madeleine's profile is standing approximately here, in the Google Maps image below, just beyond the pathway corner, and there was a kind of false grotto cave behind him, a remnant of which is still there. The bush beyond was abloom in the film.

Below is approximately the location of where was Carlotta's grave, only this screenshot I made off Google Maps is on the wrong side of it. Carlotta's grave would have been in the concrete area before the iron inclosure, Madeleine standing before it.

John then follows Madeleine to the Palace of the Legion of Honor art museum which, its space vacant of the world's hubbub, feels very nearly as sacred as the church, demanding reverent silence, filled with portraits of the dead, and furnishings and art removed from practical use, set specifically and especially apart for preservation and contemplation.

We may wonder at how bold John is to follow Madeleine into Gallery 6, where Madeleine is seated before a portrait, especially considering how many times they have come within inches of one another. At Ernie's, Madeleine had paused for several seconds within a foot of John at the bar to wait for Elster. At the florist's, as John had stood peering through a crack in the back door at Marilyn, she had approached within a few feet of him. At the cemetery, again, she had paused and stood within a couple of feet of John. Because she doesn't ever look directly at him, behaving as though lost in her thoughts, as if she doesn't see him, Detective John assumes he remains invisible. Coming up behind her, yet still at a distance, he notices her bouquet of roses, which contains also blue forget-me-nots, replicates the nosegay held by the woman in the painting before which Madeleine sits, and that Madeleine's hair is coiffed with the same spiral as we see in the woman's portrait.

John inquires of a docent or attendant as to the painting and is told, "That's Carlotta", Carlotta Valdes. He acquires from the individual a book of holdings at the museum that has an image of the painting.

The spiral in Carlotta's hair, which Madeleine copies, reminds of John's vertigo, and the graphics at the opening of the film that can symbolize eternity conceived of as dizzying revolutions—and I automatically think of Nietzche's concept of the eternal return that has influenced so many.

In the book, Roger is told of a portrait of Madeleine's great-grandmother, but as it is at Paul and Madeleine's home he doesn't see it until after Madeleine's death. In the book, Roger and Madeleine together visit a museum, the Louvre, but there is no gazing upon a portrait of her great-grandmother. There is no observation of a bouquet of Carlotta's that is recreated by Madeleine. Roger is told, by Paul, of Madeleine recreating her great-grandmother's hairstyle, which is a heavy bun on her neck, but there is no mention of the engrossing spiral of the eternal return as we have here, depicted with the abyss at its center.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Though the curl of Carlotta's bun is associated only with Madeleine's coiffure, I think the editing and mirroring placement of John demands we also consider how Carlotta relates to him. The spiral of the bun is echoed in John's ear. Carlotta leaning against the pillar is mirrored in John leaning against the painting that is Carle Vanloo's "An Allegory of Architecture", in which three children display a facade while two others labor on its building. The plan, in that painting, is for Madame de Pompadour's Chateau de Bellevue (house of the beautiful view) at Meudon, which was constructed as a "pleasure house". For her dressing room, Francois Boucher painted La Toilette de Venus, which speaks to Pompadour's role as Louis XV's mistress. As for the children, this was part of a series of paintings by Vanloo on allegories of the arts—music, sculpture etcetera—children taking the part of adults in all of them. Children playing adult roles was a favored subject of French royals at the ttime, and a sigh of "Ah, charming, cute innocence" may be one's response, even when the play is overtly mischievous, but they also to me suggest a meditation on how, with our fleeting life spans, against the infinite we are as infants, this sensibility communicated in Vanloo's allegory of sculpture painting in which a child works on the bust of an elegant man while a bust on the floor behind gazes in horror at what-we-don't-know, maybe the past, maybe the grave, maybe premonitions of the French Revolution and the guillotine several decades in the future. Vanloo's paintings of the allegories were conceived for decorative panels at Bellevue, and it seems Pompadour liked them because they were cute kids and she liked art of cute kids and cherubs as cute kids. She thought the cute kid aspect was what was fresh and novel for the treatment of the allegories. She collected a lot of art of cute cherubs.

One may notice that in the "An Allegory of Architecture" painting a child ascends a ladder, and recollect that at Ernie's there had been the tabula scalata image, both of which may remind of the ascent up the ladder at the film's beginning, during the chase scene, following the credits in which the woman's face had been featured part by part, then then her pupil as a gateway to ceaseless spirals. We will remember John's attempt to ascend the yellow step-ladder that Midge, the commercial artist had brought to him, when he was practicing desensitization, but with Midge he had glanced out her window and been seized by vertigo with her apartment being several stories up.

The painting to the screen left of John is Portrait of a Gentleman, an anonymous individual, which seems an appropriate pairing as John's attention is on the Portrait of Carlotta, gifted by an anonymous individual. In the book, Carlotta (Pauline) herself painted the portrait.

When we consider John's positioning against the "An Allegory of Architecture" painting and that it mirrors Carlotta's positioning against a pillar, we should also consider the role of the pillar in relationship to "portals of the past" as discussed at length in part one of the analysis.

After the visit to the museum, John follows Madeleine to a faded Victorian mansion, at Eddy and Gough Streets, the McKittrick Hotel. Parking her car directly out front, which she had done at the cemetery and the museum, and would be unlikely to do if hiding her activities, especially at a hotel, Madeleine enters and is soon seen drawing the shade open in a front window on the second floor. John parks a car behind her...

Yes, and let's discuss his parking behind her for a moment. When Madeleine exited the florist's, John's car was sitting directly behind her car in the alley. John parked his car behind her car, on the street, at the Mission Dolores, and Madeleine would have exited the Mission first when returning to her car. John didn't park his car directly behind Madeleine's at the museum, but he didn't tuck it away in a corner either. And now, at the McKittrick Hotel, John parks his car one car back behind Madeleine's on the street. Hitchcock isn't hiding any of this from us. Maybe it's just a lot easier to follow people without them noticing than I imagine and I'm the only person who doesn't know this--or it could, again, have to do with, from the beginning, Madeleine's (intentional) intimacy with John, which he views as accidental and oblivious, and John's careless, captivated intimacy with her.

John enters the building as well and speaks to the proprietor who at first he doesn't see as she is hidden by the counter. Played by Ellen Corby, who was 3 years younger than Jimmy Stewart, born in 1911, she is portrayed in attire, aspect, voice and walk as an elderly woman. At first she guards the privacy of her guests but answers John's questions after he displays his old detective's badge. She identifies the occupant of the room above them as Carlotta Valdes, not Madeleine Elster. Other than revealing that Carlotta had first leased the room two weeks previous, the proprietor's role is one that polishes Carlotta as chaste, quiet, innocent—however mysterious—she not using the room for assignations, not receiving visitors. But when John requests that his inquiries not be mentioned to Carlotta when she comes back down, the proprietor protests that Carlotta hasn't been there, pointing out her key is still on the board. John insists he saw her, and, finally, to assuage John's curiosity, she goes up to check the room, which gives an opportunity for us to view a circular stained glass window set in a dome in the ceiling of the second floor. This stained glass window was in drawings of the set design, so it must be significant to the hotel, and though we may be reminded of the stained glass doors of Ernie's, churches also come to mind, which do figure strongly in the film. Grace Cathedral is within view of Madeleine's apartment building, a block over from it. St. Paulus Lutheran Church, a Gothic cathedral, is catty-corner from the McKittrick Hotel. These are prominent edifices on the movie screen. And, after all, both Madeleine and Judy will fall from the bell tower of San Juan Bautista.

There is no evidence of Madeleine in the room and her car is gone. Madeleine's disappearance is spoken of as being the big MacGuffin in this film, Hitchcock describing a MacGuffin as "the thing that the characters on the screen worry about but the audience doesn't care about", but that seems facetious because the audience does care how Madeleine disappeared, how she wasn't seen entering by the proprietor and how neither John nor the proprietor saw her leave. This little mystery does pale later, overwhelmed by the mystery of Madeleine, and then by the reveal of John's having been conned, but it initially augments the supernatural and ghostly aspect of Madeleine and is never explained. As something inexplicable, Hitchcock told Novak it was simple conversational fodder, an "icebox talk scene", just something for the audience to talk about.

I've thought it may be that we take the proprietor too much at face value, just as John does, just as he is so suckered in by the story of Madeleine, he is so easily conned by his old "friend" Elster, and Judy in her role as Madeleine.

In the book, Roger (John) twice follows Madeleine to a hotel. Before her death, having been told already of the old family mansion that is now a hotel, John follows Madeleine to it but she signs in as Madeleine and doesn't pull a disappearing act. However, after speaking with the proprietor, as Roger leaves, he thinks, "I've lost the knack...I no longer know how to squeeze the truth out of people."

Toward the end of the book, Renee (Judy) will be followed to a similar hotel where she gives her name as her great-grandmother's (Pauline Lagerlac in the novel) though Renee has protested she knows nothing about Madeleine or Pauline. Asked later why she did so, she tells Roger it was to erase from his mind any thoughts of her as Renee when she escapes him—for she plans to get away, deploring him—leaving him only his obsession with Madeleine-Pauline.

John has been so easily conned that Roger's self-observation on his inability to get the truth out of people is something of a revelation. He's not good at his work, at least not any longer. He no longer knows how to squeeze the truth out of people. And it makes me wonder if the proprietor in Vertigo has her part to play in misdirecting John and heightening the mystery of Madeleine, paid by Gavin or the false Madeleine. After the viewer learns the truth about Elster and how Judy acted the part of Madeleine, why shouldn't we suspect the proprietor as well? The McKittrick Hotel is large, and soon after Madeleine was observed at the window she might have left by another exit.

Or it could simply be that, crouched behind her counter, the manger or proprietor somehow didn't notice Madeleine enter and she slipped out by means of another exit that she'd earlier scouted out.

Why go through this bother though? Why lead John to the hotel and then give him the slip? For one thing, from now on Madeleine will have such an air of ethereality for John that it will seem to him she could disappear at any moment.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Proprietor: Yes? Is there something I can do for you?

John: Yes. You run this hotel?

Proprietor: Yes.

John: Would you tell me who has the room on the second floor in the corner, that corner?

Proprietor: Oh, I'm afraid we couldn't give out information of that sort. Well, our clients are entitled to their privacy, you know. And I do believe it's against the law. Of course, I don't think any of them would mind really, but still l...(John shows her his badge)...oh, dear, has she done something wrong?

John: No, please answer my question.

Proprietor: I can't imagine that sweet girl with that dear face...

John: What's her name?

Proprietor: Valdés. Miss Valdés. Spanish, you know.

John: Carlotta Valdés?

Proprietor: Yeah, that's it. Sweet name, isn't it? Foreign, but sweet.

John: How long has she had the room?

Proprietor: It must be two weeks. Her rent's due tomorrow.

John: Does she sleep here ever?

Proprietor: No, she just comes to sit two or three times a week.

I don't ask questions, you know, as long as they're well-behaved. But, I must say...

John: When she comes down, don't say I've been here.

Proprietor: Oh, but she hasn't been here today.

John: I just saw her come in five minutes ago.

Proprietor: No, she hasn't been here at all. Well, I would have seen her, you know.

I've been right here all the time, putting olive oil on my rubber plant leaves.

And there. there, you see? Her key is on the rack.

John: Would you please go up and look?

Proprietor: To her room?

John: That's right.

Proprietor: Yes, of course, if you ask. But it does seem silly. -

John: Thank you.

Proprietor: Oh, Mr. Detective? Would you like to come and look?

John: Her car's gone.

Proprietor: What car?

It has been reported, on the gray suit that Madeleine wears, how Kim Novak was adamant about not wearing gray, she felt it the wrong color for her, and Hitchcock refused to relent, so he is compared with John who forces Judy to change and buys her the gray suit she'd worn as Madeleine. True, considering what we know about Hitchcock's deplorable abuse of Tippi Hedren, it's natural and right to see in John Hitchcock's manipulativeness and obsession. As for the story of Novak's not wanting to wear the gray suit and Hitchcock insisting on it, if one isn't only a personality playing themselves, isn't it the nature of the acting profession, in theater and film, to assume a character and attributes that the director and writer feel belong to the character. And, actually, n an interview with Robert Osbourne of TCM, Novak has clarified that she quickly realized Hitchcock was right, the gray suit was appropriate, that it made her uncomfortable, that it was shaping how she should feel.

If we refer to the original book, in it Madeleine wore a gray suit, and Roger obsessively associates the gray suit with her.

And all of a sudden she was standing on the pavement. Flavières promptly dropped his paper, got up and crossed the road. She was wearing a grey suit, very tight at the waist, and her black handbag was tucked under her arm. She looked round her as she finished putting on her gloves. Some delicate white lace fluttered at her throat. Her forehead and eyes were half concealed by a short veil which masked her gracefully. Another portrait! La Femme au Loup.

Later in the book, gray is associated with the color of memory, the past, all that is gray becoming a feast of the dead.

Female ghosts are often called "the gray lady".

But a woman as a "loup", a wolf, seems to mean something equivalent to a heartthrob, a seducer, so there is this aspect to consider as well. As for the painting, I don't know if the one being referred to in the novel is "Portrait de Femme au Loup Noir" by Claude Arnulphy, or Jean Ubaghs, "Femme au Loup", or Hugo Scheiber's, or Andre Durain's. Perhaps Scheiber's as like Jean Metzinger's painting, already referenced in the book, it isn't realism.

Claude Arnulphy's "Portrait de Femme au Loup Noir"

Jean Ubagh's "Femme au Loup"

Hugo Scheiber's "Femme au Loup"

Andre Durain's "Femme au Loup"

Madeleine never wears a veil or mask in the film. I would say that she is perfectly masked as the serene and innocent yet psychically tortured Madeleine, but when John sees Judy on the street he is so profoundly reminded of Madeleine he must follow her, speak to her. They aren't the same, he must change her in order to find in her the Madeleine he wants to possess, but she is recognizable to the extent that Roger and John both believe she must be Madeleine even as they accept that she is not. What John will have to struggle with, after Judy's death, is whether she remained a "loup" to the bitter end, or if she did indeed love him as she professed.

Just because the novel had Madeleine in a gray suit doesn't mean Hitchcock couldn't have put her in another color, but in Vertigo, with the exception of the elegant black evening shawl with the emerald accent, and John's robe, Madeleine only wears black, white, or gray. Color is reserved for Judy.

Though not exactly the same, Doris Day wore a gray suit in key scenes in The Man Who Knew too Much, a film in which her son was kidnapped.

I explore the reason for the gray suit, in respect of the novel, more fully in the You've Been There Before section, in which we glimpse a book in John's apartment titled, Coloring Photographs. When John is in the hospital, he listens to music that originates in a ritual to dispel the poison of the wolf spider.

Recycled Movie Costumes shows that the gown painted in the Carlotta portrait, and which we also see worn by Joanne Genthon in John's dream sequence, is the same as a very significant one worn by Olivia de Havilland in The Heiress, adapted from Henry James' Washington Square. Briefly, The Heiress concerns Catherine, a daughter of a wealthy physician, and the question as to whether or not a suitor, Morris (Montgomery Cliff), may be only after her for her money. There are some very important differences between Washington Square and The Heiress, so in consideration of the use of this gown in Vertigo, perhaps what we should concentrate on is the vulnerability of the naive heiress, who is ultimately abandoned by Morris when her father reduces her inheritance. The book, not denying that the suitor is a golddigger, makes a case for the suitor having been a good candidate for a husband as Catherine loves him and he would likely have treated her well, whereas her father emotionally abuses her. Her mother having died in childbirth, the father never forgave his daughter for this, or the fact she wasn't a boy. He continually compares her to the mother and openly declares her unattractive and socially awkward, assuring Catherine that no man will want to marry her who isn't attracted by her inheritance. The only reason the suitor Catherine loved wasn't a candidate was Morris didn't have money as well to bring into the union—which he ably points out to the father is pure classism, and that the father couldn't care less about his daughter's happiness or emotional well-being. As for the suitor, he treats Catherine well, bolsters her confidence, makes her feel wanted, makes her feel she has value, and she begins to blossom. But, had they married, would Morris have continued to treat Catherine well or not? Some are of the opinion that he would have, others that he wouldn't.

The situation is much like Hitchcock's 1941 film, Suspicion, which requires its own analysis. It stars Olivia's sister, Joan Fontaine, as an heiress who is, as with Catherine, made to feel unattractive and awkward by her father. Cary Grant suddenly appears as a suitor and sweeps her off her feet. Against her father's wishes, she marries him. From the beginning, we are uncertain about Grant's devotion to her, if he is a golddigger and only after her money. She eventually comes to believe that he intends to murder her, which doesn't happen, and in the end Grant renews her conviction in his love for her. But I am of the opinion that though this is where the film seemingly ends for an audience that is as Joan, completely gaslit, the story continues on off screen and Grant kills Joan.

The Carlotta gown, which originally belonged to Catherine's mother in The Heiress, is worn by her to the party where she meets Morris. She arrives at the ball disappointed by her father's criticism of how she looks in the gown, that her mother's beauty meant that she wore the gown, whereas the gown wears Catherine. She leaves the party in a state of excitement due the unexpected potential of a suitor who danced with her and wants to visit her.

We may wonder if Vertigo is a continuation of the Suspicion storyline, and also reveals what Hitchcock believes may have happened had Morris married Catherine in The Heiress. In Vertigo the husband does prove to be a golddigger who marries a wealthy woman only for her money and eventually murders his wife after her parents have died. Cary Grant finally does away with Joan; Montgomery gets rid of Olivia.

|

|

The last time—our first time—at Midge's apartment, Johnny was already seated when the scene opened. This time, we watch as Johnny enters her apartment, Midge seated before the window in the main room polishing a spectator pump. As far as their relationship, what this tells us is that it remains so friendly and intimate that it seems Johnny may have his own key and may not even feel the need to knock. Or perhaps he did knock and the scene opens just after his calling out that it's him and Midge telling him to enter (Hitchcock later reveals this wouldn't be the case). What we do know is that Midge is seated in the office portion of her main room when he enters, that she doesn't have to get up and go over and answer the door and let him in. And, of course, Johnny is so intimate that he's going to step into her kitchen and fix himself a drink. This is the kind of intimacy between them that Hitchcock wants to communicate. Johnny probably may as well consider Midge's a second home—he even asks her if she wants a drink as well (she does not), becoming the host, so physically in tune with the space that he comfortably knows where everything is and is economical in his movements the way that someone very familiar with a space becomes economical with their movements, humans being inclined to not waste energy. But it is also not his apartment for it seems to be thoroughly Midge's own, with no suggestion of Johnny's influence. These are not his records, his books, his art, his furnishings, his anything--except for, maybe, probably, when he settles in to read the newspaper he likely prefers the bentwood lounge chair and ottoman.

That spectator shoe, let's take a look at it. Why? Because it pings. It tells me to look at it.

If we look at its history, we find that the spectator shoe was also known as the co-respondent shoe. The co-respondent, in a divorce case, was the person charged with committing adultery with the married person who was being charged by their spouse with having committed adultery. Typically, it was the man having an affair with someone's wife. How did this shoe become associated with such activity? Worldwidewords relates that in flagrante evidence being required, housemaids in hotels might supplement their income in this way, supplying evidence. Shoes were left outside a hotel room's door to be cleaned but were an "easily identifiable signal that hanky-panky should be assumed to be taking place within". All of such knowledge would have had to have been popularized by the 1920s-1930s when spectators were at their height in popularity. But they had also been considered a shoe that was tacky and thus worn by a certain kind of individual, like a cad, a person, perhaps, who dressed too loudly, too flashily. Despite this history, and perhaps itself the origin of the co-respondent association, was Edward VII's abdication of his throne in order to marry Bessie Wallis Warfield who met Edward VII while she was still married to Ernest Simpson, which was her second marriage, and divorced Simpson to marry Edward. I read this was perhaps another reason for "co-respondent" as Wallis was well known for wearing spectator shoes. I also read it was because Prince Edward liked the style and wore them for golf. Prince Edward would have been the co-respondent had Ernest Simpson wanted to press the issue.

Yet the shoes were made, initially, for sports, the holes in the leather providing cooling ventilation. Later, in the 1920s, these two-toned shoes replaced the white spats that had been fashionably worn by wealthy men over their highly-polished patents but became commonplace wear during WWI because of their adoption in the military for providing warmth and waterproofing in the trenches.

That's perhaps few too many sentences to devote to Midge polishing a spectator shoe, but I do so because I think it's probable the shoe points to John's relationship with Madeleine that has already budded in his mind. And by the end of this section, after the trip to the book store, Midge knows John well enough to ask if Madeleine is pretty, suspecting John is deeply involved and that this would be why. It may be why she broke up with John back in college and why he's still available. For all we know, John may have a thing for unavailable, married women, relationships he must keep a secret, for which reason he's always perceived as available, and Midge had become aware he wasn't ready to settle down, he wasn't the marrying type, at least not yet. It's all right to speculate. By the close of this analysis I change my mind and decide no woman will be right for him for long, but it's all right to toss around other ideas and I may change my mind yet again.

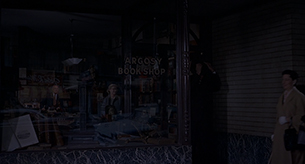

Johnny wanting to know where to learn the social gossip of old San Francisco, Midge takes him down to the Argosy Book Shop, which was fashioned after San Francisco's Argonaut Book Shop (not located at around 225 Powell, as this shop is, where was the Manx Hotel, but at 336 Kearny). There was also a well-known bookstore in New York called the Argosy. And speaking of adultery, might we consider a very ancient case of adultery via the Argosy name. The legend of Medea has her assisting Jason, of the Argonauts, in capturing the Golden Fleece, which means she commits also a deadly betrayal of her family for sake of her lover. They married, and had children, but then he threw her over for Glauce, the daughter of the King of Corinth. Medea's vengeance was to give a poisoned wedding dress to Glauce, which clung to her flesh and burned her alive, then she killed their children and escaped, aided by the gods. She later married Aegeus, father of Theseus.

Leibel relates how Carlotta, from a mission down south, was a dancer and singer who became the mistress of a wealthy married man. She had a child by him, which he took into his home, his wife unable to have children. Carlotta discarded, her child torn from her, she committed suicide. Rear Window appears to be referenced during the Argosy visit for as Leibel relates his story of Carlotta, that her wealthy lover "kept the child and threw her away", we see in the second floor windows of the MacIntosh (men's clothing store) across the street, a man in a white shirt who is at the screen right of the store, then goes to where another person is seated, doing some work, positioned at the center of the long, center window of the second floor of the building, and gives them such a vigorous back massage that for a moment it could almost look like physical violence. Then he leaves the person and returns to the left side. There's nothing happenstance about this, the Argosy is a set, and the street is all rear screen projection from the Powell street location. One might find it humorous but for Carlotta's abysmal story and the screen darkening ominously while fate is related.

Leibel confirms that the house down on Gough was one that was built for Carlotta by the man. The problem is that, as I've already pointed out, Carlotta died in 1857, while the house is of a later Victorian style, bult in 1888. Gough and Eddy weren't even platted until about 1858, in response to the Van Ness Ordinances of 1856 to 1858. Was another house already in that spot, though the Western Addition wasn't platted until 1856-1858, and the later McKittrick Hotel has been confused with it? We expect Leibel to be right as this is his expertise and the film has gone to him for knowledge. But John's life is right now being bound up in a web of lies, and into that web could also happen just plain error. Why? Because the film is determined to place Carlotta, the story of the woman with an illegitimate child, both in the brand new San Francisco of the 1849ers and later in the Victorian era. I'll get into the why of this in the next section.

"There are many such stories," Leibel says, which gives the potential excuse that he has blended and confused two stories.

Already mentioned, as Leibel has spoken of Carlotta's sadness, the screen dims, first near imperceptibly, then rapidly, so that it seems something wrong has happened with the film. Hitchcock has set this up for the explanation to be that when night descends, it happens so rapidly in that area, light is so quickly lost, in a couple of minutes dusk has completely fallen, and as Midge and John leave the shop the lights are turned on inside. But this darkening is also coincident with the relation of Carlotta's death, her suicide, how men had the wealth and power then to seize children and ruin people's lives, and one feels a supernatural element to the the dark.

John drops Midge off at her apartment, and she, against his protestations, determines to go have a look at the portrait of Carlotta herself, she finding preposterous the story that Elster's wife is possessed by her great-grandmother, and understanding that Johnny has become too deeply involved because of a beautiful woman. Midge is right, of course. It's too bad John wouldn't listen to her, but had John listened to her there would be no Vertigo.

John's own hapless innocence is so successfully sold the audience, the idea that he has been drawn into this to be only a witness to Madeleine's suicide, that it may take a while for the audience member to realize that John has been selected not only to be a witness but to become involved, to have, at least, an emotional affair with Madeleine, it being taken for granted he will fall in love with her, to be the shamed and silent co-respondent or the co-respondent who might be openly accused if such a turn is needed, which means that Elster is aware not only of John's accident and vertigo but that John has a weakness for unavailable, beautiful women, and that he will have no compunction at all against betraying an old friend with his wife.

|

|

|

|

John: Midge, who do you know that's an authority on San Francisco history?

Midge: That's the kind of greeting a girl likes.

None of this: "Hello, you look wonderful" stuff, just a good straight, "Who do you know that's an authority on San Francisco."

John: Want a drink?

Midge: No, thanks.

John: Well, who do you? You know everybody.

Midge: Professor Saunders over in Berkeley.

John: No, No, I don't mean that kind of history.

I mean the small stuff, you know, people you never heard of.

Midge: Oh, you mean the gay old bohemian days of gay old San Francisco.

Juicy stories, like who shot who in the Embarcadero in August, 1879.

John: Yeah, that's right.

Midge: Pop Leibel.

John: Who?

Midge: Pop Leibel. He owns the Argosy Book Shop.

Why? What do you want to know?

John: I want to know who shot who in the Embarcadero in August, 1879.

Midge: Hey, wait a minute. You're not a detective anymore. What's going on?

John: You know him well?

Midge: Who?

John: Pop Leibel.

Midge: Oh, sure.

John: Well, come on. I want you to introduce me. Get your hat.

Midge (grabbing her coat and running out the door): I don't need a hat. Hey, Johnny, what's it all about?

John: Hey, well, wait a minute.

(At the Argosy.)

Leibel: Yes, I remember. Carlotta.

The beautiful Carlotta. The sad Carlotta.

John: What does an old house on the corner of Eddy and Gough have to do with Carlotta Valdés?

Leibel: It was hers. It was built for her many years ago.

John: By whom?

Leibel: By uh, by uhm, no, the name I do not remember. A rich man. A powerful man.

(To John.) Cigarette?

John: No, thank you.

Leibel: Cigarette, miss?

Midge: No, thanks.

Leibel: It is not an unusual story. She came from somewhere small, to the south of the city. Some say from a mission settlement. Young, yes, very young. And she was found dancing and singing in cabaret by that man, and he took her and built for her the great house in the Western Addition. And uh

there was a child. Yes, that's it. The child. The child. I cannot tell you exactly how much time passed or how much happiness there was, but then he threw her away.

He had no other children. His wife had no children. So, he kept the child and threw her away. You know, a man could do that in those days. They had the power and the freedom. And she became the sad Carlotta.

Alone in the great house, walking the streets alone, her clothes becoming old and patched and dirty. And, the mad Carlotta, stopping people in the streets to ask, "Where is my child? Have you seen my child?"

Midge: Poor thing.

John: And she died.

Leibel: She died.

John: How?

Leibel: By her own hand. There are many such stories.

John: Well, thank you very much.

Leibel: You are welcome.

John: I appreciate it. Good-bye.

Leibel: Good-bye.

Midge: Hey, wait a minute! Good-bye, Pop. Thanks a lot. (Back out on the sidewalk.) Now then, Johnny-O, pay me.

John: For what?

Midge: For bringing you here. Come on, tell.

John: There's nothing to tell.

Midge: You'll tell or you'll be back in that corset. Ah, come on, Johnny, please.

John: Come on. I'll take you home.

(Parks before her apartment.) Here you are.

Midge: You haven't told me everything.

John: No, I've told you enough.

Midge: Who's the guy and who's the wife?

John: Out. I've got things to do.

Midge: I know. The one that phoned. Your old college chum, Elster.

John: Midge, out, please.

Midge: The idea is the beautiful, mad Carlotta has come back from the dead and taken possession of Elster's wife.

Now, Johnny, really. Come on.

John: I'm not telling you what I think, I'm telling you what he thinks.

Midge: What do you think?

John: Well, I...

Midge: Is she pretty?

John: Carlotta?

Midge: No, not Carlotta. Elster's wife.

John: Yes. I guess you'd consider that she would...

Midge: I think I'll go take a look at that portrait. Good-bye.

John: Midge...Midge!

Midge: Good-bye!

The tour of wealth that is unimaginable to the majority of us plebes continues. The first meeting of John and Elster had them enveloped with the wood-paneled extravagance of Elster's office. The location of their second meeting is a set said to be based on the Pacific Union Club located across from the Brockelbank where Elster and Madeline live. Its rooms massive, the building occupying a whole block, it was once the home of James Clair Flood, who, according to Celebrity Net Worth, in 2012 dollars would rank as one of the 40 richest Americans with a worth of $34 billion built largely on silver mines. As for the Pacific Union Club, its members list is described as "no Democrats, no women, and no reporters", one of the most elite boys clubs in the United States and the most elite one on the West Coast, according to Wikipedia. Wives and women are allowed on the grounds only by invitation, areas forbidden to them, and under some circumstances they must use the rear rather than the front entrance. In its incarnation as Flood's home, construction was completed on it in 1888, the same year as the "McKittrick Hotel". Flood didn't enjoy the mansion long as he died in 1889. The 1906 earthquake wrecked the building's interior, but it was salvaged, its interior remodeled, and in 1910 opened as the clubhouse.

It's at this club that Elster learned about Carlotta Valdés, what he wasn't told my Madeleine's mother. The old Flood mansion. Catty-corner from where the Towne mansion once stood, the entry porch of which became the Portals of the Past which Madeleine now visits down at the Golden Gate Park. And what's John thinking about while he talks to Elster? How lovely is Madeleine and what does she look like in her bed, where she's perhaps sleeping, in the Elster apartment at the Brocklebank right across the street from where Elster is meeting with him at the elite Pacific Union Club in a room that not even wealthy Madeleine can enter, because she's a woman, but because of her wealth, business and prestige her husband can.

Elster: You've done well, Scottie. You're good at your job.

John: That's Carlotta Valdés.

Elster: Yes.

John: There are things you didn't tell me.

Elster: I didn't know where she'd lead you.

John: But you knew about this.

Elster: Oh, yes. You notice the way she does her hair? You know, there's something else.

My wife, Madeleine, has several pieces of jewelry that belonged to Carlotta.

She inherited them.

Never wore them, they were too old-fashioned. Until now.

Now, when she's alone, she takes them out and looks at them, handles them gently, curiously, puts them on and stares at herself in the mirror, and then goes into that other world, is someone else again.

John: Now, Carlotta Valdés was what, your wife's grandmother?

Elster: Great-grandmother.

The child who was taken from her, whose loss drove Carlotta mad and to her death, was Madeleine's grandmother. And the McKittrick Hotel is the old Valdés home.

John: I think that explains it. Anyone could become obsessed with the past with a background like that.

Elster: She never heard of Carlotta Valdés.

John: She knows nothing of a grave out at the Mission Dolores? Or that old house on Eddy Street?

The portrait at the Palace of the Legion of...

Elster: Nothing.

John: Well, what, when she goes to these places...

Elster: She's no longer my wife.

John: Well, how do you know all these things she doesn't?

Elster: Her mother told me most of them before she died.

I dug out the rest for myself here.

John: Why wouldn't she tell her daughter?

Elster: Natural fear.

Her grandmother went insane, took her own life.

Her blood is in Madeleine.

John (picks up his drink): Boy, I need this.

Another building that survived the earthquake of 1906 was the Fairmont Hotel, that stands next the Union Pacific Club and also the Brocklebank.

Let's stick a little while longer with James Clair Flood, whose mansion became the boys' club where Gavin Elster meets with John about Madeleine.

James Clair Flood had a son named James Leary Flood. While she was appearing at a San Francisco dance hall, James Leary Flood, considered a playboy by some, fell in love with Marie Rosina "Rose" Fritz, a dancer who had been with the Victoria Loftus British Blondes.

The Victoria Loftus British Blondes are known for having brought burlesque to the United States. Rose, who the 1870 Lexington, Lafayette, Missouri census shows as 9 years of age, is reported to have run away when she was 16—or maybe it was when she was 15—and that she married a traveling salesman in St. Louis, but when her father tracked her down he had the marriage annulled. Soon after, she ran off again and joined the Victoria Loftus British Blondes, using the stage name Violet Elwood.

Unless there was another Violet Elwood, the below photo may show her. The picture is stated to have been taken in 1875, and if this is correct then Rose was about 14 at the time.

The Troupe was in San Francisco in 1879 and it seems that was when Rose settled there. She adopted the stage name Petey and worked at the Bella Union, a burlesque house that was by then located at 805 Kearny but had originally opened in 1849 and had passed through several other locations.

Who shot who on the Embarcado in August of 1879? I don't know but a Sam Tetlow was a famed owner of the Bella Union, his partner being William Skeantlebury, and in July of 1880 they had a quarrel and some say it was on the street and some say it was in the theater's bar that Tetlow shot Skeantlebury after Skeantlebury had struck him. There was a trial, Tetlow was sentenced to be hanged but instead went to jail and in August of 1880 the theater passed on to the care of Patrick McAtee as a trustee. I find a news article that states Sam was acquitted of the murder in April of 1881. Another news article of April of 1882 gives Tetlow as suing McAtee. An article of 1896 declares Sam was ruined when he got out of prison and never recovered from it, a man once mighty now fallen lower than low.

There are various stories about how Rose and James Leary met but in all of them the Flood family was disapproving. They are said to have paid her $25,000 to get lost, but James Leary pursued her to Italy where they married in 1887-1888, when the Flood mansion was being built. (In another story they met on a boat to Europe.) They returned to America, and Rose was never accepted by the Flood family—which I would take to mean James' sister, Cora Jane, and his mother—his father dying in 1889 and his only sibling being Cora.

Rose had that family back in Missouri and though she had run off from them they weren't estranged and benefitted quite well from the marriage. They moved to a fashionable neighborhood in Kansas City. Soon after she was married, Rose brought her sister, Maude, to live with her and James. Maude was born in 1877 so was 16 years younger than Rose .

Constance Mae (May) was born in May of 1893. She grew up in the Flood household believing she was the daughter of Rose and James Leary Flood and that her aunt was Maude. She was well known as the daughter of James Leary Flood by servants and friends, as was later reported at the trial in which she attempted to prove her paternity. Many people came forward and testified on her behalf, that they had known her, when she was a little girl, as the daughter of James and Rose.

Rose died in 1897, not long after James Leary's mother. James Leary took her body back to her family in Missouri, along with their four-year-old daughter. As Maude would later report, she and James knew very soon they were in love, and he proposed to her long before the engagement was made public. In 1899, James Leary Flood and Maude married.

An 1899 news article about the wedding of Maud and James states Constance May Flood, the ring bearer, was the daughter of Maud's sister, Rose, the first wife of James.

Maude and James took off, leaving Constance with the Fritz family. She is in their household in the 1900 census, as Constance Stearn, stated to be an adopted daughter of theirs, age given as 8, born in May 1892 in New York City. She was not however living with the Fritz family except periodically on the weekends. Soon after the marriage of Maude and James Leary, after having been left with the Fritz family, they sent her to a convent.

In 1901 she was transferred to the Ramona Convent in San Gabriel, Los Angeles where she would live, her education and board paid for by a trust fund of $7000 that ran out when she was about 17. She had not seen the Fritz family since living in California. She had not seen the Floods. She remembered Rose and James Leary Flood as her parents, but who had set up the trust fund was kept secret from her, and when she attempted to contact James Leary Flood he didn't respond. Eventually an intermediary related to her that her parents were named Stearns and were both deceased. Turned out of the convent when the money ran out, alone in the world, she was taken in by the family of some friends from the convent. She married John Patrick Gavin, a bank teller.

After James Leary died, in 1926, Constance Mae, now Constance Mae Gavin, decided to press the matter of her paternity and claim a share of James Leary's estate as his daughter. There was a trial, and though the jury was sympathetic with Rose, the judge ordered the jury to find in favor of the Flood estate, then when the California Supreme Court overturned this decision and ordered a new trial the Floods offered Constance $1.2 million (she had been seeking a $2,000,000 share) if she would drop her claim to being the daughter of James. Constance was ill. She had been through years of litigation. She had been through years of anguish. She accepted and spent several months in the hospital recovering her mental health. Afterward, she led a quiet life with her husband.

Constance Mae had believed her mother was Rose but it turned out her mother was likely a woman named Eudora Ellen Forde, a music hall girl, who was herself the daughter of an actress, Alfredeta (Wilson) Forde. As it turned out, Constance was born 11 May 1893, as Constance Marguerite Stearn, in San Francisco, to Eudora Ellen Forde, who took the last name of Stearn to disguise the fact she was unmarried. Constance's childhood nurse came forward and testified that one day she was instructed by Rose Flood, in 1897, to deliver an envelope to a home at 211 Mason Street, that of Eudora Forde. Constance was brought along, and when Alfredeta saw her she wanted a hug but Constance refused as she didn't know her. Alfredeta complained it was a shame the girl didn't know her own grandmother. Returning home, the nurse told Rose Flood what had been said, confused, and Rose explained that James Leary Flood was Constance's father and that they'd taken Constance in as their child as Rose was unable to have children. The nurse related that Flood constantly referred to Constance as "my little baby". The coachman testified that Constance was known as Flood's child. Neighbors testified. Well-heeled neighbors testified. Writings were submitted, from Constance's childhood, that gave her as Constance Mae Flood.

There was never any question at the trial that Constance had lived with the Floods—what was being contested was her relationship to them. Maud said she was just a child, abandoned by her father, her mother impoverished, who Rose had taken in and cared for, and after Rose died it was thought best to just end all that. Fritz family relatives, financially supported by the Flood family, testified that Constance was just some poor girl that the Flood family had taken care of and there was no relationship. Maud's brother said that a ship's register ton which James Leary Flood had listed Constance as his daughter meant nothing, nor did it mean anything that Constance still possessed articles given her as a child upon which her initials were inscribed as CMF.

It was revealed that in 1898 Eudora had signed away all rights to Constance but that the Floods had never officially adopted the girl.

It was revealed that Eudora was consistently getting get paid quite a lot of money by the Floods before Rose's death, which supported Eudora and her family, and after Rose's death she was still showing up asking for money.

Eudora had shown up finally seeming to ask for Constance's return. But, no, she didn't want her to be returned, she said she couldn't raise Constance in the manner to which she was accustomed. She did want more money however. In 1901 she signed an affidavit that she was the mother of Constance and that an Edward Stearn was the father. In exchange for this she received $5000 ($32,000 today).

The first time Constance had met Eudora was with the nurse. The second time she met Eudora was at the Mission Dolores, Eudora coming to say goodbye to Constance before she was went to the Ramona Convent.

They wouldn't meet again until Eudora learned Constance was going to trial to prove her paternity. Remember, when Constance set out to prove her paternity, she believed that Rose was her mother.

From "TIME" magazine, Monday, August 17, 1931:

JIM FLOOD'S GIRL

Three decades had passed since muddy San Francisco had been transformed to a city built on nuggets and gold dust. A new social order was being created; life was becoming stable; respectability and stolidity were in the air. But there were still those who lived high, wide & handsome. The old Poodle Dog, Tail's, the Cliff House and Coffee Dan's had no lack of carefree customers.

A leader of the merrier element was James Leary Flood. In his blood was an instinct for the fleshpots; in his bank, money for it. His father was James Clair ("Bonanza King") Flood, onetime saloon keeper, later owner of the Comstock Lode with William S. O'Brien, James G. Fair and John W. Mackay, father of Postal Telegraph's Clarence Hungerford Mackay. Said to be the richest claim in the world, the Comstock yielded $340,000,000 pay dirt between 1864 and 1884, brought fame and fortune to the combination of Mackay, Flood, O'Brien & Fair.

Jim Flood inherited the bulk of his father's estate in 1889. All San Francisco knew of his high living, of the beauty of "Jim Flood's girl, Pete Fritz," a German girl who got her start in Shanghai. In the same year his father died San Francisco was scandalized to hear that Jim Flood's girl had left her widely known occupation, that he had married her. His friends avoided him for a while, but he and his Girl lived happily together, adopted a child call Constance May. When Rosina ("Pete") Fritz Flood died her husband promised to marry her sister Maud Lee. The second Mrs. Flood was a plump, quiet, homebody, well-liked in San Francisco. Yet scandal does not die. In the little Redwood City court house (in the fashionable Peninsula district) spectators thronged last week to hear the Flood Affair dragged into the open. It was story-of-the-week for the newspapers.

Cause of last week's ado was baby Constance May, now Mrs. John P. Gavin 38, wife of a Los Angeles bank teller. Since 1925 Mrs. Gavin has claimed to be Jim Flood's illegitimate daughter, has sought a daughter's share (two-ninths) in his $18,000,000 estate. At first she named the first Mrs. Flood as her mother. Later she claimed as her maternal parent a Mrs. Eudora Forde Willette, onetime music hall girl.

Heading the counsel for the defense were the venerable, silver-haired, massive Garrett William McEnerney, once Jim Flood's personal attorney, and stocky, nervous Theodore Roche. Their arguments were that the first Mrs. Flood would not have adopted her husband's bastard, the Jim Flood would have given an adopted daughter all the affection and kindness which Mrs. Gavin said proved she was his real daughter. Thus did they refute old Flood retainers, coachmen, gardeners, nurses & neighbors who testified he often called Constance May "My Baby," "My little daughter."

Eudora's story would change dramatically several times. First, she would testify that James Leary Flood was the father, which was her story for years. She said she had met him at the Russ House (a luxury hotel) where he was having a party, through an introduction by the proprietor of the Lick House (another luxury hotel). She said he'd wined and dined her, and they had an affair and Constance was born. James promised to take care of the child. In August of 1893, when Constance was three months old, Eudora went to the Flood home to meet Rose and told her of the affair. Rose accepted the child as her own, being unable to have children, and she and James took Constance in.

Eudora claimed to have arrived in San Francisco in June of 1892 and that it was during that summer she met James Flood "by the Golden Gate". A 1929 article on the trial continues, "It was on a summer day in the Russ house, a famous old San Francisco hotel, that the proprietor introduced the slim brunette entertainer to Jim Flood, wealthy playboy of the west. She was a happy, vivacious girl of 18 then. Jim Flood was a dashing, good looking, youngish man, an outstanding figure in the glittering boom city because of his personality and because he was heir to the bonanza millions. He was a man about town, whose attentions would have flattered any young girl. He courted the little music hall entertainer persistently from the hour of their meeting, she said. Mrs. Willette declared that she did not know then, not until months later, that he was married. There were notes, dinners, suppers; Jim plied his suit fervently and waxed ardent over the many bottles of wine the two shared..." She would meet him at his rooms in the Maison Rieche. This article on the trial reads that when the baby was six weeks old she took her to Rose, told the story of how Constance was James Flood's child, James Flood conceded this was true, and Rose decided to accept the child as her own, James agreeing.

Then one day Eudora surprised Constance by showing up in court and proclaiming that she had lied all this time, that prior testimony and all her previous affidavits were false. She said that James Leary Flood wasn't the father, it was instead a man named Cannon who had been a theater property man at the old Grove Street theater. She gave several different stories of how she heard that she ought to go see Rose Flood for help. So she did and she said Rose went into another room and spoke with "Jim" (James Flood, who Eudora now said she had never previously met in her life) about taking in the girl, and that James thought she would just be trouble but Rose said she wanted a baby as she couldn't have any children.

Eudora's mother, when now giving testimony on this, said it was disgusting to even suggest that Flood was the father, a terrible falsehood. She acknowledged she had received support from Maud Flood but that it had nothing to do with her testimony.

Constance died in 1951. Her husband had died before her and she left her money to charity. Eudora fought for the estate and I don't know what the outcome was. Eudora died in 1957. In 1957, a book was published, The Strange Case of Constance Flood, by Willa Iverson. This was still big news at the time that Vertigo was being filmed. Willa was a reporter and said that Constance was a fine woman who had been devastated by the circumstances and confusion of her life. I should read the book to get the full story but it's a bit costly.

I've seen articles published that still assume Rose was Constance's mother. One such article ("Eden, Journal of the California Garden and Landscape History Society", 2006 Vol. 9. No. 3) is on James Leary Flood's estate, Alma Dale, in the Bear Creek Redwoods. The land purchased in 1894, the mansion was apparently built for his wife, Rose, who had not been accepted in San Francisco society and preferred the mountains. That article assumes Constance was the daughter of Rose and James Flood, but it does appear Eudora was the mother instead. After Rose's death, Maude and James Flood built a new country estate and sold Alma Dale in 1905, a place that would have been also Constance's home. Even if James Leary Flood wasn't the father, it couldn't be more calloused to abandon a girl that Rose wanted as her child, to fund her education in a convent until she reached seventeen and never have anything to do with her again. Maud was reported to be jealous of Constance and wanted her gone. Perhaps she was jealous of Rose as well and wanted to rid the family of that tie to Rose, who would have grown up as Rose's daughter.

Is that how Gavin Elster gets the first name of Gavin? Discussing Gavin with Midge, John made note of Gavin Elser being an unusual name, which perhaps tags it for us as something which has history and meaning.

Is this why Madeleine visits her mother's grave at the Mission Dolores?

Is this why the clubhouse where Gavin receives John is modeled on the Pacific Union Club, the old James Flood mansion, and it's where he says he learned everything about Madeleine and her great-grandmother? What he hadn't learned from her mother, he dug up there—in the old Flood mansion?

Hitchcock chose to have "Madeleine, wife of Elster Gavin" buried in Section I (plot 409) of Cypress Lawn Cemetery. The massive Flood mausoleum is at Cypress Lawn Cemetery as well, on the other side of Section H, in their own little island of a section.

In the book upon which Vertigo is based, Madeleine's great-grandmother is not a singer, not a dancer. She does not have an affair with a wealthy, married man. She is already monied. She marries and has a child and commits suicide but that is the only tragic thing about her story, that she committed suicide--if we are even to believe that, I don't know. Her child was not taken from her to live with its wealthy father and his wife who couldn't have children. She didn't wander the streets grieving for her lost child, her clothes becoming worn out and dirty. She didn't lose her mind for grief over the child who was taken from her and commit suicide because of this.

She was a woman who had wanted to be a nun. She was a woman who had painted her own portrait and her family had kept it and passed it down from child to grandchild to great-grandchild.

We may assume it is John's second day following Madeleine. The action opens with a close-up of him driving, viewed from the front. We then see from his point-of-view, that he is following Madeleine's car down a curving tree-lined street on a steep hillside, in the distance the

monumental Palace of Fine Arts, built for the Panama-Pacific Exposition of 1915, and which the architect, Bernard Maybeck, wished would remind of "the mortality of grandeur and the vanity of human wishes". The poster for the Panama-Pacific Exposition showed a woman clad in a Roman style white tunic that was bound about the breasts and shoulders with some decoration highlighting her assets, a long palla or mantle draped behind her. She leaned against a half-wall, two pillars beyond, the floor before her littered with broken, delicately fluted Corinthian columns and shattered terra-cotta color brick. This would seem peculiar for it was only nine short years since the earthquake of 1906, and one wonders how this might have dangerously reminded of the devastating earthquake yet was to celebrate the completion of the Panama Canal. Indeed, though all the buildings of the expo were intended to, as Wikipedia puts it, "fall to pieces at the close of the fair (reportedly because the architect believed every great city needed ruins)", the exposition itself must remind of the earthquake through its display of how San Francisco had subsequently risen from the ashes.

Bearing such titles as "The Struggle for the Beautiful", the Palace of Fine Arts was decorated with bas-reliefs concerning the arts and Greek/Roman mythology. The accompanying colonnade, most strikingly, is decorated at the top with copies of a statue of a woman whose strong back is turned to the city and world, hair curled atop her head, each figure draped over the corner of a seeming ossuary. These are the weeping maidens. Coincidentally, the powerful backs of these maidens who perpetually honor the dead remind of, though she is vibrant and alive, our first glimpse of Madeleine at Ernie's, her back to us, powerful, not diminutive, not fragile, perfectly angled and dressed for its sea of exposed back to conjure maximum allure.

We have already brushed by one of Bernard Maybeck's many other buildings, at 1010 Gough and Eddy on the corner opposite from the McKittrick Hotel, which was originally the Fortmann Mansion. That Maybeck building, of Mediterranean design, is barely glimpsed, and dates to 1889, built for the Associated Charities of San Francisco, which changed its name later to the Family Services Agency.

John follows Madeleine back to the Palace of the Legion of Honor.The long, establishing shot of the building shows us also Anna Vaughn Hyatt's sculptures, "Joan of Arc", and "El Cid Campeador", honoring the medieval Spanish knight Rodrigo Diaz. Opened in 1924, the building is a full-scale replica of the French Pavilion at the same 1915 Panama–Pacific International Exposition as appeared The Palace of Fine Arts. Wikipedia states the French Pavilion was a three-quarter-scale version of the Palais de la Légion d'Honneur (also known as the Hôtel de Salm) built in Paris in 1782 by Pierre Rousseau. The Palace of the Legion of Honor is loaded with columns and more columns, and it's interesting to me that Hitchcock occupies a fair amount of scenic territory with buildings introduced by the 1915 exposition that was supposed to show San Francisco having risen out of the ashes while also depicting "the mortality of grandeur and the vanity of human wishes".

Madeleine, dressed in black, enters, followed at a distance by John. Inside, again, Madeleine visits the portrait of her ancestor, Carlotta, resting on a bench before it as John watches from the rotunda, shielded by large pillars. Bernard Maybeck said he thought the visiting of museums should be communicated as a serious and somewhat sad business. Or did he say somber and sad? Perhaps because museums more often than not display the effects and portraits of dead people. Such as Madeleine's Carlotta. Again, Madeleine carries a bouquet of flowers, which means they would have first stopped at the flower shop, but this time wrapped around the bouquet is a bit of white lace scarf, perhaps Madeleine's, so the bouquet has a bridal air to it—yet she's dressed in black. Back outside, again Hitchcock has us, as with the first time, watch as Madeleine's car departs the museum, followed by John's.

They travel down a road toward the Golden Gate Bridge and we are given a close-up of John, in his car, seeming entirely unperturbed, perhaps expecting much the same routine as the first day. But they are not going to the McKittrick Hotel this time. Instead, Madeleine's car passes through the gate of the Presidio park. John follows her past a sign that reads Fort Point Road, down the waterfront, passing through brief breaks of light between the shadows cast by the great cliff above. At the foot of the Golden Gate Bridge, they park at the great brick hulk of a fortress at Fort Point, built between 1853 and 1861 on what was once a 90 foot portion of cliff that had been blasted down to 15 feet above sea level. Carlotta, having died in 1857, would have never been acquainted with this fortress. Instead she might have known the Castillo de San Joaquin which the brick fortress replaced. She would have been acquainted perhaps with the 90 foot cliff that stood where they park their cars, the sole visitors, and John really far too obvious as he climbs out of his car to watch Madeleine, a long white scarf blowing in the wind about her neck, walking beyond the Fort, out of sight. John follows and watches as she stands beside the water's edge. We have a close-up of the bouquet of flowers which Madeleine tears apart with her gloved hands, tossing fragments of the blossoms into the water. We see the blossoms in the water, John cautiously watching, then Madeleine abandoning the rest of the bouquet to the waves.

She leaps into the water.

The music surges urgently, shrills and circles.

John rushes to the water's edge to stand where she had stood, whipping off his jacket, throwing away his hat. Switch to a very obvious set as he climbs down a flight of stairs to the water and dives in. He reaches and grasps Madeleine who floats on her back in the green waves, her mouth tightly pursed against the water. As he reaches her, Madeleine's mouth opens in a gasp. John negotiates her over to the sea wall and oh so heroically and vulnerably, gasping for breath, carries a conveniently accommodating Madeleine, however unconscious, up the stairs, away from the dark shadows of the point, to her car, where he struggles to open the back passenger door, the supposed unconscious Madeleine's right arm draped about his neck, and rests her in the car's rear seat. Had Carlotta dropped off the side of the 90 foot cliff that had previously been there, she'd be dead. Perhaps that is what we are supposed to assume, that Carlotta dove into the water from that point, where the fort and then the Golden Gate Bridge would later be built. That this is how she had taken her own life. But Madeleine has instead leaped from a short sea wall. Not from the cliff. Not from the Golden Gate Bridge which was for so long notorious as a successful launch pad for suicides.

John calls her name, "Madeleine, Madeleine!" She raises her head, as if she hears, briefly opens her eyes upon him, and lets it fall again.

Those who watch the film and are unaware of its plot may consider that Kim Novak doesn't play very effectively the part of a person who has attempted to drown themselves, but then because of this we may already be feeling a little funny about it all, about this attempted suicide. Those who watch the film and already know what happens may still wonder if Kim Novak was supposed to read for the audience as a real-attempted-suicide and didn't quite get it right, or if she was supposed to let her self-preservation come through as Judy acting Madeleine. What is most profoundly communicated, John pulling Madeleine through the water, carrying her up the stairs, to her car, is how vulnerable is John made by this, believing he has rescued Madeleine from death.

In the next section I'll compare the attempted suicide by water in the book with that in the movie.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Continue to Part 3

December 2021. Approx 12,500 words, 25 pages of single-spaced text.

Return to the top of the page.