STANLEY KUBRICK'S A CLOCKWORK ORANGE

Go to TOC for this film ( (which has also a statement on purpose and manner of analysis and a disclaimer as to caveat emptor and my knowing anything authoritatively, which I do not, but I do try to not know earnestly, with some discretion, and considerable thought).

PART EIGHT

TOC and Supplemental Posts | Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Films Home

LINKS TO SECTIONS OF THE ANALYSIS ON THIS PAGE:

Alex Resurrected, Shots 596 through 597

The hermetic pelican and the red blood of the dragon.

Alex Makes the Papers Again, Prompting a Visit From His Parents, Shots 598 through 60

Art, reconciliation and the great work. On paisley and Basel and basilisks. The gift basket. Alex Burgess.

The Psychiatrist, Shots 608 through 640

The Duke of York pub and the psychiatrist. Humbert Humbert's Divine Edgar's Ulalume and Psyche. A comparison of the subject of deja vu in A Clockwork Orange and in The Shining. Memory and forgetfulness.

An Understanding Between Friends, Shots 641 through

Comparing the bars of light to the restraining lines in prison. A round of applause.

What about that ending?

Dustan Makavege's 1965 film Man is Not a Bird

How it All Plays Together

ALEX RESURRECTED

THE HERMETIC PELICAN AND THE RED BLOOD OF THE DRAGON

596 MS The hardware of an orthopedic hospital bed. (2:01:04)

There's a brief space of blackness and no fade-in. Should this count as a separate frame?

The sound of Alex breathing. The camera pans up and over his mangled body bound partly in casts, wearing a diaper. A swath of bandage on his chest has a red spot of blood in the middle of it. A tube conveying blood is inserted on the high right side of his chest, the insertion point covered with bandage.

ALEX (VO): I jumped, oh, my brothers, and I fell hard, but I did not snuff it. If I had snuffed it, I would not be here to tell what I told. I came back to life after a long black black gap of what might have been a million years.

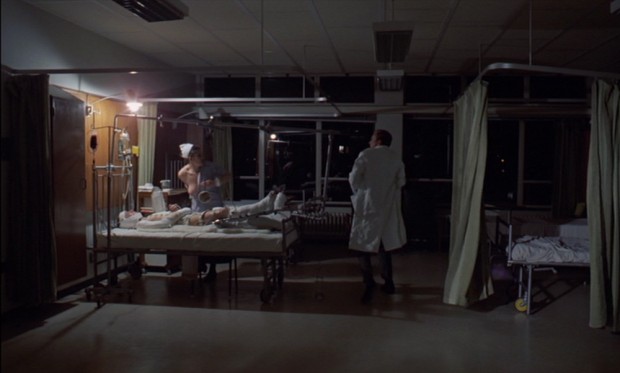

597 LS The hospital room. (2:01:39)

Alex's bed is to screen left, a white bulb overhanging his face. To the right is another bed wrapped in curtain.

Alex, waking, groans. We hear a responsive sexual moan from behind a curtain opposite in the room. Alex again groans. Again the woman's moan. Alex again groans, and then the woman. Alex groans, and this time, in response, we hear footsteps. A nurse, her breasts hanging out of her dress, stumbles out from behind the drape, followed by a doctor doing up his pants.

NURSE: He's recovered consciousness, doctor!

Alex had already compared himself with an infant in an earlier scene where the bodybuilder carried him down the steps to the waiting Alexander. Alex's coming "back to life after a long black black gap of what might have been a million years" is here depicted by Kubrick as a birth. A nurse and a doctor are having sex and Alex wakes as if in response to this. The nurse scrambles to attend Alex, one breast hanging out over him, as if a mother's breast, Alex in his diaper.

He also looks rather like mummy, swathed in casts and bandages as he is.

Kubrick makes a comparison of Alex's suicidal leap with an act of self-sacrifice (however goaded, however provoked) through an association with the dancing Christ figures and his having become the perfect Christian, for though Alexander had wanted revenge, the conspirators also provoked him to kill himself as a sacrifice to their efforts to keep the government from instituting a clockwork orange system. Also, Kubrick has presented Alex as an anti-Christ (666), and has been associated as well with Leviathan, whose flesh would serve as food for the righteous in the "Time to Come". He is the anti-Christ as the perfect Christian, who by design, by fate, is incapable of doing wrong, a clockwork being.

The curious blood stain in the center of Alex's bandages recalls the myth of the pelican with its breast stained with blood from pecking it to feed its children, symbolic of the redemption of mankind through Christ's blood. There are other forms of the tale in which the pelican actually kills its young when they are old enough to rebel and peck it, then resurrects the young with its blood.

Alchemy was central to Rosicrucian beliefs. One of the most common alchemical symbols was the pelican. As Manly Hall explains, "The pelican feeding its young from a self-inflicted wound in its own breast is accepted as an appropriate symbol of both sacrifice and resurrection. To the Christian mystic, the pelican signifies Christ, who saved humanity (the baby birds) through the sacrifice of His own blood." To Rosicrucians, the pelican represented one of the vessels in which the experiments of alchemy are performed and its blood that mysterious tincture [the Philosopher's Stone] by which the base metals (the seven baby birds) are transmuted into spiritual gold." The pelican was often shown under a "rosy cross" or "rose croix", as seen here. Together, the pelican and the rose symbolize human and divine affection. The mother bird represents the love of the Creator, while the rose, a rearrangement of the letters of the Greek word eros (love), represents humans' love for each other.

Source: Manly P. Hall. An Encyclopedic Outline of of Masonic, Hermetic, Qabbalistic and Rosicrucian Symbolical Philosophy

Pursuing the alchemical angle, The Golden Tripod, or Three Choice Chemical Tracts relates,

He, then, who would prepare the incombustible sulphur of the Sages, must look for our sulphur in a substance in which it is incombustible, which can only be after its body has been absorbed by the salt sea, and again rejected by it. Then it must be so exalted as to shine more brightly than all the stars of heaven, and in its essence it must have an abundance of blood, like the Pelican, which wounds its own breast, and, without any diminution of its strength, nourishes and rears up many young ones with its blood. This Tincture is the Rose of our Masters, of purple hue, called also the red blood of the Dragon, or the purple cloak many times folded with which the Queen of Salvation is covered, and by which all metals are regenerated in colour.

ALEX MAKES THE PAPERS AGAIN, PROMPTING A VISIT FROM HIS PARENTS

ART, RECONCILIATION AND THE GREAT WORK - ON PAISLEY AND BASEL AND BASILISKS - THE GIFT BASKET - ALEX BURGESS

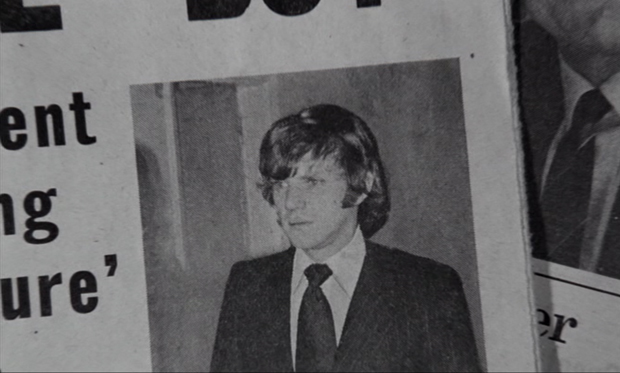

598 CU Alex in the MIRROR paper. (2:02:11)

The camera zooms out.

The Funeral Music for Queen Mary plays.

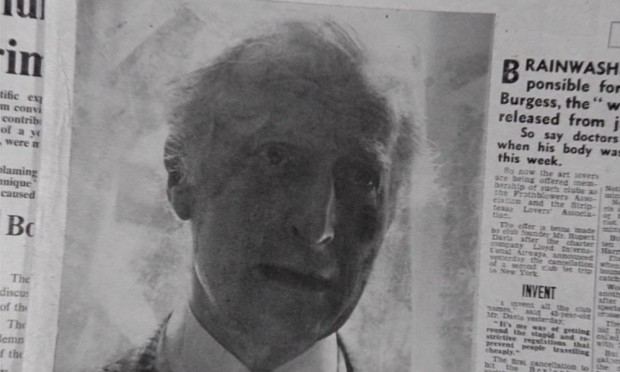

599 CU Minister of the Interior photo in the paper with the article on brainwashing. (2:02:15)

The camera zooms out.

Below the headline that can be partially read, "Brainwashing", reads an article, "So, now the art lovers are being offered membership of such clubs as the Frothblowers Association and the Striptease Lovers' Association. The offer is being made by club founder Mr. Rupert Davis after the charter company Lloyd International Airways announced yesterday the cancellation of a second club jet trip to New York." This followed by INVENT. "I invent all the club names," said 43-year-old Mr. Davis yesterday. "It's my way of getting round the stupid and restrictive regulations that prevent people traveling cheaply."

600 CU THE TIMES paper. (2:02:19)

No. 63,485 Ninepence THE TIMES. "Government accused of inhuman means in crime reform," reads the headline. "Accusations that scientific experiments, designed to reform convicted criminals, have directly contributed to the suicide attempt of a youth just released from prison, were made last night. Doctors and MPs were blaming the so-called Ludovico Technique for the mental pressures that caused one of the first of its subjects to try and kill himself two days ago. Our political staff says the government is suffering acute embarrassment, since these charges of inhuman experiments are bound to call into question the whole policy of law and order which it has made a plank in its election programme." Below is a headline reading "Author's Last..." beside another headline, "Boy Attempts Suicide..."

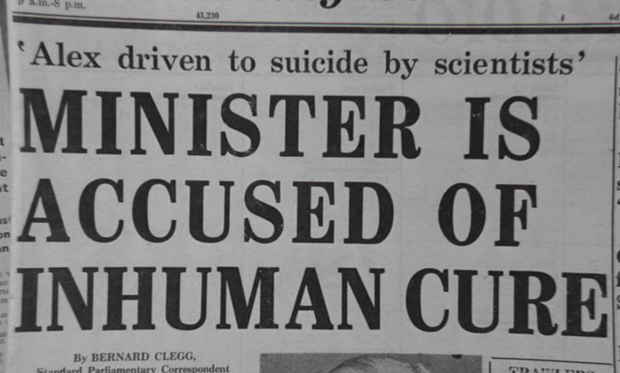

601 CU "Alex Driven to Suicide by Scientists - Minister is Accused of Inhuman Cure" headline in another paper, the article by Bernard Clegg (2:02:23)

602 CU "Government is Murderer - Doctors Charge as Alex Recovers" headline of article by Frank Beck, above the brainwashing story of shot 595. (2:02:28)

"Brainwashing techniques were responsible for the suicide bid of Alex Burgess, the 'wonder cure' boy murderer..."

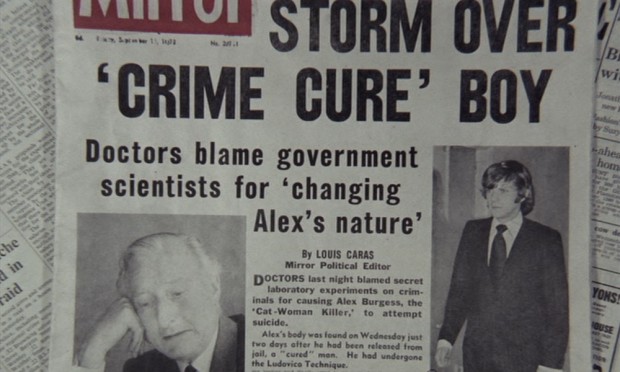

603 CU the MIRROR paper which had been in shot 594. "Storm Over 'Crime Cure' Boy" (2:02:31)

The month is September but the date is otherwise difficult to read. The previous paper had shown "Weather: warm, dry, sunny".

"Doctors blame government scientists for 'changing Alex's nature', by Louis Carras, Mirror Political Editor. "Doctors last night blamed secret laboratory experiments on criminals for causing Alex Burgess, the Cat-Woman Killer, to attempt suicide. Alex's body was found on Wednesday just two days after he had been released from jail, a 'cured' man. He had undergone the Ludovico Technique."

604 CU Another paper with the headline "Alex's death bid blamed on brain men - Minister under attack" with the byline of John Anscombe. (2:02:36)

Under a "Comment" section to the side is "Give Us All the Facts" and then, "All together now, children ... two sixpences..."

To look at the papers. When I see "Storm Over" I take it as meaning the storm is over rather than continuing, especially as we then view the papers forecasting sunny and clear weather, which will fit with Alex telling the Minister of the Interior that his understanding is as clear as an azure sky.

Next, the word "invent" attracts attention. Alex has previously noted his operating by inspiration, such as the inspiration he received from the music at the marina when he took leadership of his gang again, and he also received inspiration, via brainwashing, to leap from the window. Now the word "invent" appears which can be taken as discovery, though some accounts give it as original thought. Original thought would be a break from clockwork programming.

The story below one of the headlines on Alex's brainwashing is instead about art lovers being now offered membership in clubs with names like the Frothblowers Association and The Striptease Lover's Association. Because one of the significant themes of Alex's hospital stay has to do with reconciliation (he is about to reconcile with his parents, then with the government, and finally with society at large, not to mention himself), and because of the film ending with Alex in a jubilant and joyful sex scene, I'm going to suggest what we have here is a reference to Temperance, the "Daughter of the Reconcilers, the Bringer Forth of Life", sometimes the Art card in the Tarot. As with the Lovers card it has to do with the mystical alchemical marriage, of duality and the mixing and rectifying of opposites. Some express its journey as being through a tunnel of the dark night of the soul towards the light. This would fit with Alex's waking after a long black, black interval. Rebirth and the bearing of the divine child, also associated with Temperance, suit well what is happening at this stage in the film.

605 LS Alex's bed from an opposing view. (2:02:40)

Cut to Alex in his bed, alone on a hospital ward. His mother and dad are visiting, she dressed in a bright red vinyl coat and hat. They have brought a fruit basket which they've set on his bed. They greet him as he wakes and ask how he is, if he's feeling better.

DAD: Hello, lad.

MUM: Hello, son. How are ya?

DAD: Are you feeling better?

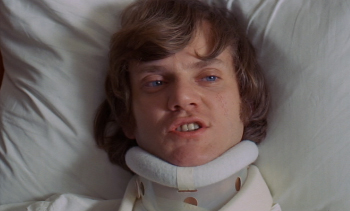

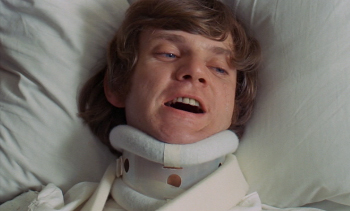

606 MCU Alex's head in a cast. (2:02:58)

Shot of Alex, his head cradled in a cast, his face stitched to either side of his mouth, the blood stain still over his heart.

ALEX (struggling to speak): What gives old man, Pee and Em? What makes...

607 MCU Alex's parents from his POV. (2:02:10)

ALEX: ...you think you are welcome?

A shot of his parents from his perspective reveals his mother in a pink wig. In the basket are grapes, oranges, bananas and a package of something that reads, "...AT ME".

Alex's mother breaks down in tears, his father consoling.

DAD: There, there, now, mother, it's all right. He doesn't mean it. (To Alex.) You were in the papers again, son. They said they had done great wrong to you. They said how the government drove you to try and do yourself in. And when you think about it son, maybe it was our fault, too, in a way. Your home's your home, when all's said and done, son.

Prominently, Alex's father wears a purple paisley tie. It is so prominent I thought it might be wise to look up exactly what paisley means. As it turns out it's the name of the town where the cloth was originally made, and comes from the Latin "basilica", which seems to come from "basileus", or king. The etymological dictionary then refers one to basil.

Wait, wasn't Alex's snake named Basel? Or Basil?

The basil plant was confused with "basiliscus" (a royal plant from the word king) because, I read, it was supposed to be an antidote to the venom of the basilisk.

Basilisk comes from the Latin "basiiliscus", from the Greek "basiliskos",meaning little king, diminutive of "basileus", king.

Thus the basilisk as the king of snakes, its glare instantly murderous as was its foul, venomous breath. It too was linked with transmutations into gold in alchemy.

Maybe only a fluke, this paisley tie, but we do have Basil/Basel/Bazel, the snake, which wasn't in the book, and I think it all ties in again with Leviathan which, in the world to come, was to serve as food for the righteous. I won't go into this too much here as I've already discussed it at length in earlier sections.

Oranges. What do we have here but Alex's dad and mum apparently presenting him with a basket of fruit wrapped in cellophane, presenting oranges and bananas and grapes in the box which likely reads EAT ME but we are only able to see AT ME, so acronyms could be, MEAT, TAME. It would seem odd that while being deconditioned, he is provided oranges to eat and from now on will be drinking orange fluids.

Alexander, the writer, has also been represented as being a dual Alex, a father figure, a brother, and he, we will learn, is...gone. The newspapers show "Author's last words" which is suggestive, and when Alex later asks what happened to him the only reply is that he was put away where he can do him no harm. Kubrick likes to deal with dual natures, dual personas. The newspapers multiple times describe the "body" of Alex having been found, and as we see we can also infer a death of the writer as well.

Alex's body was found.

Rather like Alex had died and yet he lives.

THE PSYCHIATRIST

THE DUKE OF YORK PUB AND THE PSYCHIATRIST - HUMBERT HUMBERT'S DIVINE EDGAR's "ULALUME" AND PSYCHE - A COMPARISON OF THE SUBJECT OF DEJA VU IN A CLOCKWORK ORANGE AND DEJA VU IN THE SHINING - MEMORY AND FORGETFULNESS

608 LS Hospital corridor. (2:03:57)

Cut to a doctor rolling a cart down a hallway, past a nurse's desk, past an officer to whom she says "Good morning" as she enters the ward which Alex has all to himself, he now sitting up against a pile of pillows, still wrapped in casts, but his head now out of the head cast, propped by a neck brace. He has a tabloid on his lap.

PSYCHIATRIST: Good morning.

ALEX: Good morning, missus.

PSYCHIATRIST: How are you feeling today?

ALEX: Fine, fine.

PSYCHIATRIST: Good. (She removes the paper from his lap.) May I?

609 MS Alex's bed, 3/4 view. (2:04:19)

The psychiatrist places the paper on the stand beside his bed on which is fruit and the package of "(E)AT ME". There is also a bottle of orange colored drink.

She is dressed in a deep indigo wig. Her dress is red and orange with a print of diamond shapes across the chest.

DR. TAYLOR: I'm Dr. Taylor.

ALEX: I haven't seen you before.

DR. TAYLOR: I'm your psychiatrist.

ALEX: Psychiatrist? Do I need one?

DR. TAYLOR: Just part of hospital routine.

ALEX: What are we going to do? Talk about me sex life?

610 MCU Dr. Taylor. (2:04:30)

DR. TAYLOR: No. I'm going to show you some slides, and you're going to tell me what you think about them. All right?

611 MCU Alex. (2:04:37)

On his left cheek is a a nasty scar complete with stitch holes.

ALEX: Oh, jolly good!

612 MCU Dr. Taylor. (2:04:39)

613 MCU Alex. (02:04:41)

ALEX: Do you know anything about dreams?

614 MS 3/4 view of Alex's bed. (2:04:42)

DR. TAYLOR (setting up the viewing apparatus): Something, yes.

ALEX: Do you know what they mean?

DR. TAYLOR (pulling out a clipboard and pen): Perhaps. You concerned about something?

615 MCU Alex. (2:04:47)

ALEX: No, no, no, not concerned really, but, uh, I've been having this really nasty dream. Very nasty.

616 MCU Dr. Taylor. (2:04:55)

ALEX: It's like, uhm, well...

617 MCU Alex. (2:04:59)

ALEX: When I was all smashed up, you know, and half awake and unconscious like, I kept having this dream, like all these doctors were playing around with me gulliver. You know, like the inside of my brain. I seem to have this dream...

Shot 610 | Shot 611 |

|  |

Shot 612 | Shot 613 |

|  |

Shot 614 | Shot 615 |

|  |

Shot 616 | Shot 617 |

|  |

618 MCU Dr. Taylor. (2:05:12)

ALEX: ...over and over again. Do you think it means anything?

DR. TAYLOR (smiling and laughing after a look of discomfort): Patients who have sustained the kind of brain injuries you have often have dreams of this sort. It's all part of the recovery process.

619 MCU Alex. (2:05:24)

ALEX: Ah.

620 MCU Dr. Taylor. (2:05:25)

DR. TAYLOR: Now then. Each of these slides needs a reply from one of the people in the picture. You tell me what you think the person would say. All right?

ALEX: Righty right.

621 MCU Slide of a peacock and two men. (2:05:37)

DR. TAYLOR (reading off the slide): Isn't the plumage beautiful?

622 MCU Alex. (2:05:42)

ALEX (struggling for an answer): I just say what the other person would say?

DR. TAYLOR: Yes.

ALEX: Isn't the plumage beautiful...

623 MCU Dr. Taylor. (2:05:48)

DR. TAYLOR: Yes, well, don't think about it too long. Just say the first thing that pops into your mind.

624 MCU Alex. (2:05:53)

ALEX: Cabbages, knickers, uh, it's not got a...a beak!

DR. TAYLOR: Good.

Though the peacock does indeed appear to have a beak.

Alex laughs.

625 MCU switching to the next slide of a woman facing two men. The woman is the one speaking. (2:06:06)

DR. TAYLOR: The boy you always quarreled with...

626 MCU Dr. Taylor. (2:06:08)

DR. TAYLOR: ...is seriously ill?

627 MCU Alex. (2:06:12)

ALEX: My mind's a blank...uh, the boy...And I'll smash your face for you, you blockos. (He laughs.)

DR. TAYLOR: Good.

628 MCU Switching to the next slide on the viewer which is a nude woman in bed asking "What do you want" of a man on a ladder at her open window. (2:06:20)

DR. TAYLOR: What do you want?

629 MCU Alex. (2:06:24)

ALEX: Uh, no time for the old in and out, love. I've just come to read the meter.

630 MCU Dr. Taylor. (2:06:29)

DR. TAYLOR: Good!

631 MCU Switching to the next slide on the viewer, two men in a clock shop, one behind a counter, another holding a watch. The clocks all read 3:00 or 12:15. (2:06:33)

DR. TAYLOR: You sold me a crummy watch, I want my money back.

632 MCU Alex. (2:06:38)

ALEX: You know what you can do with that watch? Stick it up your ass!

DR. TAYLOR: Good.

He cackles with delight.

633 MCU Switching to the next slide which is of a woman holding a nest of speckled eggs up to a man and saying "You can do whatever you like with these". (2:06:45)

DR. TAYLOR: You can do whatever you like with these.

634 MCU Alex. (2:06:48)

ALEX: Eggy wegs. I would like to smash em. And pick em all up and throw...OW! (He's accidentally pounded his thigh, preventing him from saying more.) Fucking hell.

635 MCU Dr. Taylor. (2:07:03)

DR. TAYLOR: Well, there. That's all there is to it.

636 MCU Alex. (2:07:05)

DR. TAYLOR: Are you all right?

ALEX: Hope so. Is that the end, then?

DR. TAYLOR: Yes.

ALEX: I was quite enjoying that.

637 MCU Dr. Taylor. (2:07:13)

DR. TAYLOR: I'm glad.

638 MCU Alex. (2:07:14)

ALEX: How many did I get right?

639 MCU Dr. TAYLOR. (2:07:15)

DR. TAYLOR: Oh, it's not that kind of a test. But you seem well on the way to making a complete recovery.

Shot 619 | Shot 620 |

|  |

Shot 621 | Shot 622 |

|  |

Shot 623 | Shot 624 |

|  |

Shot 625 | Shot 626 |

|  |

Shot 627 | Shot 628 |

|  |

Shot 629 | Shot 630 |

|  |

Shot 631 | Shot 632 |

|  |

Shot 633 | Shot 634 |

|  |

Shot 635 | Shot 636 |

|  |

Shot 637 | Shot 638 |

|  |

Shot 639 | Shot 640 |

|  |

640 MCU Alex. (2:07:20)

ALEX: When do I get out of here, then?

DR. TAYLOR: I'm sure it won't be long now.

ALEX (VO): So, I waited. And, oh, my brothers...

I'm pretty well convinced that Dr. Taylor, the psychiatrist, is a dual character. I don't see in the credits where the waitress at the Duke of York club is identified. Perhaps she is and I just haven't caught it. Three uncredited women characters are identified at IMDB as being at the Duke of York but they are all given as "old lady". To me, the psychiatrist looks much like the waitress in the Duke of York. The waitress was serving an orange drink to another table at the pub, and here we see on Alex's nightstand a bottle of orange drink, orange drink being all that he has to drink from now on. I could be completely wrong.

In section seven I wrote on the action at the Duke of York being placed in Edgware, where we saw a diamond design, and the house where Alex makes his suicide leap, also showing a diamond design, being Edgwarebury. I had noted how Edgware comes from Edgi weir (weir being pond) and how it had a correspondance to a scene in Lolita (action only in the movie, not in the book) in which Humbert tells Lo a poem by the "divine Edgar" (edge), one which is on "weir" and "dim" and then is "egged" on by her to hungrily consume an egg she teasingly holds over his head, the words edge and egg (in the sense of goaded, incited) being related. For a little lengthier discussion on this go to section seven.

Here, as I've stated, I think the psychiatrist is played by the same woman who was the waitress at the Duke of York. The last question of her test has to do with eggs, and Alex's response is the most emphatic and violent of any reaction he's given, and yet he ends in hurting himself. He speaks of doing violence to the eggs, wanting to pick them up and smash them, but instead he hits and hurts himself and that shuts him up. Which is when Dr. Taylor finishes the test.

Alex can be violent again without becoming ill.

In the book the test instead began with the picture of the eggs and Alex simply said he'd like to smash them against a wall or cliff then viddy them smashed up, after which they went on to other questions. There was the peacock and to that he said he'd like to pull out its feathers for being so boastful. He was shown a number of other images, his responses not related, and finally a picture of the prison chaplain carrying a cross up the hill and he said he'd like to have the hammer and nails. At which point the interview ended and he was frankly told it was "deep hypnopaedia" that had been performed on him.

Pauline Taylor is the actress who plays the psychiatrist, and Kubrick has also given her character the name Taylor. This doctor character is a unification of two minor and unnamed characters in the book who have very little page time despite giving Alex the tests. Not only is she made a more significant character than in the book, whereas in the book Alex is told about the hypnopaedia, Taylor instead becomes withdrawn when Alex asks about his dreams and demures from saying anything other than what he's experiencing is part of his recovery process and due the nature of his brain injuries. She is thus a somewhat suspicious character, in that for some reason Kubrick has elected to have her not reveal to Alex anything about procedures performed on him, only telling him that he was dreaming when he said he felt people were playing with his brain.

Kubrick is also the one who represents Taylor as a psychiatrist, giving her a name, whereas in the book they were only "doctor vecks".

If we return to the "divine Edgar" and his poem "Ulalume" which Humbert had partially recited to Lolita, we see that psyche (soul, mind) is a prominent player, and thus perhaps Dr. Taylor as the psychiatrist. In Lolita, Humbert promised Lolita during the divine Edgar scene that he would never reveal any of her secrets, which is when she offered him the reward of the egg. Here, the psychiatrist (psyche) has a secret concerning Alex and his dreams she wishes not to divulge. In "Ulalume", the poem that Humbert had partly read to Lo, Poe's psyche attempts repeatedly to prevent him from following a path he will later discover leads to the tomb of his lost Ulalume. Along the way he spies the star of Astarte which his psyche mistrusts.

And now, as the night was senescent

And star-dials pointed to morn -

As the star-dials hinted of morn -

At the end of our path a liquescent

And nebulous lustre was born,

Out of which a miraculous crescent

Arose with a duplicate horn -

Astarte's bediamonded crescent

Distinct with its duplicate horn.

And I said: "She is warmer than Dian;

She rolls through an ether of sighs -

She revels in a region of sighs:

She has seen that the tears are not dry on

These cheeks, where the worm never dies,

And has come past the stars of the Lion

To point us the path to the skies -

To the Lethean peace of the skies -

Come up, in despite of the Lion,

To shine on us with her bright eyes -

Come up through the lair of the Lion,

With love in her luminous eyes."

Astarte is a fertility goddess, her name coming from a word for "womb" (so I read). Her symbols include the sphinx, hinted at above with the lion.

The Duke of York pub scene occurred prior Alex's invasion of the Cat Woman's home which had the sphinxes sitting outside on the stoop where Alex was blinded.

So, in "Ulalume", which Kubrick has quoted in Lolita--and we find is obliquely referenced here and at Edgwarebury, where Alex attempts suicide--Poe's Psyche attempts to keep him from taking a path which turns out to be one he had taken the previous year, of which he was unconscious, and thus he experiences deja vu and comes again on the tomb of Ulalume.

We find the same in The Shining, again connected with eggs, Wendy serving Jack a breakfast of eggs and as he eats it he recounts how when he'd arrived he'd experienced such deja vu he felt he knew what would be around every corner, and fell in love with it immediately. Then, later, with the Advocaat incident (Advocaat being made of eggs) he had a collision with the past, and retiring to the bathroom with the waiter is goaded and "egged on" to come to no uncertain terms with the so-called rebelliousness of his wife and son.

The main crux of the matter here is the deja vu and repetition.

Alex, when released from prison, had found himself accidentally visiting scenes from his former life. Deja vu.

We've then the same formula in The Shining of eggs/Edgar/edge experienced with deja vu and eventually a collision with the past.

Why eggs? Kubrick carries the theme from one film to the next. The eggs and deja vu in Lolita. Deja vu and Alex and eggs in A Clockwork Orange. Deja vu and Jack and eggs in The Shining.

The past repeating itself is the subject of the "Uncanny Tales" comic in Alex's prison cell, the one of the developing photo of the train running into a wagon on a track and the dialogue balloon of "Holy smoke! I've photographed something that happened a century ago!"

We've had a version of this with Alex meeting again the Irish bum, only this time he was abused, and his returning to HOME, though not recognizing it at first, just as he at first didn't recognize the bum. A cycling about into same territory though experience within it alters. My notes on Rememberance and Repetition in Kubrick's "The Shining" deal with this especially concerning Room 237.

The psychiatrist, Dr. Taylor, who appears to be the same waitress serving at the Duke of York pub, draws our attention again to Alex's cycling of experience, only here it involves a doubled woman with whom Alex didn't appear to have any interaction the first time around--if she is indeed the actress who plays the doctor also played the waitress--and appears here in an entirely different capacity as a different person. Our only information on her concerning the Duke of York pub was that she was wearing a red jumper, white shirt, and a style of wig that is recalled in the attire of Alex's mother when he returns home after his imprisonment, a style anticipated (though different) when his mother awakens him earlier in the film.

Memory and forgetfulness play a large part in the movie. When Alex meets again the Irish bum and then the writer, both times there is the initial time of non-recognition, then the realization he has met a person before or been in a certain place before. When Alex protests to his droogs, calling them to remember the old days, Dim says he doesn't recollect them though Georgie Boy says "enough" is remembered. Leviathan has been described as the "accuser", and, very simply, accusation requires memory. If there is no memory, accusation can't be made.

Alex, as we shall see, is not being returned to exactly as he was before, there is a change.

AN UNDERSTANDING BETWEEN FRIENDS

HE HIDDEN LINES OF LIGHT IN THE FLASHES - ALEX'S TOES BEHIND THE WHITE LINES - A ROUND OF APPLAUSE

641 MS Front view of an attractive nurse in blue feeding Alex from a tray over his bed. (2:07:31)

We see oranges to the side on the bedside table.

ALEX (VO): ...I got a lot better, munching away at eggie wegs and lomticks of toast, and lovely steakie wakes. And then one day they said I was going to have a very special visitor.

The nurse and Alex look to the corridor.

642 LS The corridor from Alex's room. (2:07:47)

The Minister of the Interior and a doctor and nurse enter the ward, stopping to discharge an attending officer.

DOCTOR: Just wait outside for a moment, would you, officer?

OFFICER: Yes, sir. (He exits.)

MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR: I'm afraid my change of schedule has rather thrown you. I seem to have arrived when the patient's in the middle of supper.

DOCTOR: Oh, that's quite all right, Minister, no trouble at all.

From Alex's perspective as the Minister of the Interior enters the room with a doctor and nurse.

MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR: Good evening, my boy.

ALEX: Hi, hi, hi there, my little droogies.

DOCTOR: Well, how you getting on today, young man?

643 MS The Nurse feeding Alex. (2:08:11)

ALEX (with his mouth full): Great, sir! Just great!

Shot 641 | Shot 642 |

|  |

Shot 643 | Shot 644 |

|  |

644 MS Alex's POV, the head nurse, Minister of the Interior and the doctor. (2:0:13)

DOCTOR: Can I do anything more for you, Minister?

MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR: I don't think so, Sir Leslie, thank you very much.

DOCTOR: Then, I'll leave you to it. (To the nurse feeding Alex.) Nurse?

The doctor and the two nurses exit.

MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR: Well, you seem to have a whole ward to yourself, my boy.

645 MS Alex chewing away. (2:08:26)

ALEX: Yes, sir. And a very lonely place it is, too, sir, when I wake up in the middle of the night with me pain.

646 MS Alex and the Minister of the Interior from the side of Alex's bed. (2:08:33)

MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR: Yes, well, anyway, good to see you on the mend. I kept in constant touch with the hospital, of course, and now I've come down to see you personally, to see how you're getting along.

647 MS Alex from the right of the Minister. (2:08:43)

Alex has continued to try to eat, struggling to pick up a fork, hampered by his casts.

ALEX: Ive suffered the tortures of the damned, sir, the tortures of the damned.

MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR: Yes, I can appreciate that you've had an extremely difficult...

Food drops from Alex's fork onto his bed before it can reach his mouth.

MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR: Oh, look, let me help you with that, shall I? (He takes the fork from Alex and picks up the spilled food.)

ALEX: Thank you, sir, thank you.

MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR: I can tell you with all sincerity that I, and the government of which I am a member, are deeply sorry about this my boy.

Alex pops open his mouth like a baby bird, waiting for food.

MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR: Deeply sorry. (Feeds Alex.) We tried to help you. We followed recommendations which were...

648 MCU Minister of the Interior. (2:09:09)

Dressed in a gold and black shirt and gold tie, the Minister's black suit disappears into the dark of the room behind him.

MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR: ...made to us that turned out to be wrong. An inquiry will place the responsibility where it belongs.

649 MS Alex from beyond the Minister's right. (2:09:13)

Alex pops his mouth open to be fed again.

MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR (feeding him): We want you to regard us as friends.

Just as Dr. Branom had assured Alex she wanted to be friends.

MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR: We put you right...

650 MCU Minister of the Interior. (2:09:20)

MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR: ...you're getting the best of treatment. We never wished you harm, but there are some who did, and do...

651 MS Alex from the Minister's right. (2:09:28)

His mouth pops open again for food.

MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR (feeding him): ...and I think you know who those are. There were certain people who wanted to use you for...

652 MCU Minister of the Interior. (2:09:35)

MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR: ...political ends. They would have be glad to have you dead, for they thought they could then blame it all on the government.

The minister is referring to the writer and his friends, of course.

653 MS Alex from the Minister's right. (2:09:41)

MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR: There is also a certain man...

654 MCU Minister of the Interior. (2:09:45)

MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR: ...a writer of subversive literature (feeds Alex) who has been howling for your blood. He's been mad with desire to stick a knife into you, but you're safe...

655 MS Alex from the Minister's right. (2:09:54)

MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR: ...from him now. We put him away. (Feeds Alex.) He found out that you had done wrong to him.

656 MCU Minister. (2:10:03)

MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR: At least he believed you had done wrong. He formed this idea in his head that you had been responsible for the death of someone near and dear to him.

657 MS Side view of Alex's bed. (2:10:14)

MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR: He was a menace. We put him away for his own protection, and also for yours.

658 MS Alex from the Minister's right. (2:10:20)

ALEX: Where is he now, sir?

MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR: We put him away where he can do you no harm. (Alex pops open his mouth and the Minister feeds him.) You see, we are looking after your interests. We are interested in you and when you...

659 MCU The Minister. (2:10:32)

MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR: ...leave here you will have no worries. We shall see to everything. A good job...

660 MS Alex from the Minister's right. (2:10:36)

MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR: ...on a good salary.

ALEX: What job and how much?

661 MCU Minister of the Interior. (2:10:39)

MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR: You must have an interesting job, at a salary which you would regard as adequate, not only for the job that you're going to do and in compensation for what you believe you have suffered, but also because you are helping us.

662 MS Alex from the Minister's right. (2:10:55)

ALEX: Helping you, sir?

MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR: We always help our friends, don't we?

Alex opens his mouth wide for the minister to continue feeding him.

MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR: It is no secret that this government...

663 MCU Minister of the Interior. (2:11:09)

MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR: ...has lost a lot of popularity because of you, my boy. There are some who think that at the next election we shall be out. The press has chosen to take a very unfavorable view of what we tried to do.

Shot 645 | Shot 646 |

|  |

Shot 647 | Shot 648 |

|  |

Shot 649 | Shot 650 |

|  |

Shot 651 | Shot 652 |

|  |

Shot 653 | Shot 654 |

|  |

Shot 655 | Shot 656 |

|  |

Shot 657 | Shot 658 |

|  |

Shot 659 | Shot 660 |

|  |

Shot 661 | Shot 662 |

|  |

Shot 663 | Shot 664 |

|  |

664 MS Side view of Alex's bed. (2:11:21)

MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR: But public opinion has a way of changing, and you, Alex--if I may call you Alex? (He feeds him.)

ALEX: Certainly, sir. What do they call you at home?

MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR (quelling his indignation): My name is Frederick.

665 MCU Minister of the Interior. (2:11:35)

MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR: As I was saying, Alex, you can be instrumental in changing the public's verdict.

666 MS Alex from the Minister's right. (2:16:27)

Alex has stopped eating and stares at the Minister with a knowing expression.

MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR: Do you understand, Alex?

667 MS Minister of the Interior. (2:11:49)

MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR: Do I make myself clear?

668 MS Alex from the Minister's right. (2:11:52)

Deltoid had asked earlier if he had made himself clear on Alex staying out of trouble, and Alex replies as he had to Deltoid.

ALEX: As an unmuddied lake, Fred. As clear as an azure sky of deepest summer. You can rely on me, Fred.

669 MCU Minister of the Interior. (2:12:02)

MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR: Good, good, boy. Oh yes, I understand you're fond of music. I have arranged a little surprise for you.

670 MS Alex from the Minister's right. (2:12:11)

ALEX: Surprise?

MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR: One that I hope that you will like. As a uhm...

671 MCU Minister of the Interior. (2:12:17)

MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR: ...how shall we put it, as a symbol of our new understanding. An understanding between two friends.

Shot 665 | Shot 666 |

|  |

Shot 667 | Shot 668 |

|  |

Shot 669 | Shot 670 |

|  |

Shot 671 | Shot 672 |

|  |

672 LS POV The door opposite Alex's bed, obscured by a tall speaker being pushed in and a man running through with two huge baskets of flowers. (2:12:27)

Begin Beethoven's 9th, two large speakers are rolled in and positioned opposite Alex's bed as two men with large baskets of flowers also rush in and place them left and right of his bed. Behind them enters a flood of photographers scurrying into position to take pictures, their flashes strobing and popping.

The flowers might remind us of the painting of the flowers in the vase above the stage of the derelict casino.

673 MS Alex and the Minister of the Interior from the foot of Alex's bed. (2:12:44)

They shake hands, Alex giving the thumbs up for the cameras. The Minister happily waves for the cameras.

674 MS The photographers at the foot of Alex's bed. (2:12:53)

675 MCU Alex smiling, giving the thumbs up, in the embrace of the Minister of the Interior. (2:12:57)

676 MCU The Minister of the Interior. (2:13:02)

Shot 675 | Shot 676 |

|  |

677 MCU Alex. (2:13:06)

Then the rapture that comes with the music becoming a grimace, Alex's eyes roll back in his head, the music bringing their pictures again.

678 LS Alex having intercourse with a woman in what appears to be snow or confetti. (2:13:31)

A line of men and women clothed in Edwardian costume stand to either side, the men in gray suits and top hats, suggestive of a wedding, applauding the couple.

ALEX (VO): I was cured all right.

Final credits as Gene Kelly sings "I'm Singing in the Rain".

The White Bars of Light

One will note that with the photographs I pay special attention to three flashes in particular. They happen so quickly that one barely is conscious of these bars of light flashing on the screen. Are they possibly caused by the strobes or were they inserted? (We have established elsewhere that Kubrick will slide in some quirks.) Whether or not they are possibly caused by the strobes is inconsequential to me. I'm going to work with the idea they may have meaning as white bars have significance in this film.

The white bars figured prominently in prison as a line of demarcation which he wasn't to cross.

The white bars in prison were external barriers represented symbolically by a simple line. Kubrick is drawing a correspondence between the white bars of light positioned above Alex's toes, and the white bars behind which Alex had always to keep his toes in prison. Here, I think they represent an internal such barrier that has been established, perhaps to do with Alex's reprogramming. Things seem to have been returned to the way they were, but not exactly. There is a difference. And Alex is not going to be a problem any longer.

What About That Ending?

We come to the end and the audience believes that Alex is back to his old ways but also a discordant note is struck with the final image of Alex and the woman as there is no violence in it, so the viewer may rationalize that the wildness of having sex in front of an audience is what marks this scene as the depraved mind of Alex reasserting itself unhampered by his brainwashing.

In the book, this was instead a violent scene.

There are, of course, other differences between the book and the movie concerning the end (ignoring for the moment Burgess' final chapter). First, the Minister has, in the film, an extended period during which he spoke with Alex in isolation, even feeding Alex, and when they reached their agreement, when Alex said the understanding was clear as an unmuddied lake, as an azure sky of deepest summer (this language only used with Deltoid in the novel), then the minister announced he had for Alex a surprise that was a symbol of the new understanding between two friends, at which time the press rushed in with the flowers and stereo.

In the book, the press instead enters with the Minister who several times iterates how they have put things right for Alex, that they are friends, and cajoles Alex that in exchange for his helping them he will have everything he needs and a good job. Then the present of the stereo was made to him and all left Alex alone to listen to the music.

Oh, it was gorgeosity and yumyumyum. When it came to the Scherzo I could viddy myself very clear running and running on like every light and mysterious nogas, carving the whole litso of the creeching world with my cut-throat britva. And there was the slow movement and the lovely last singing movement still to come. I was cured all right.

In the film, Kubrick cuts to the frolic and there is no violence in it at all despite what we take as a demented expression overtaking Alex's face directly preceding his fantasy, during which he announces he is cured.

We have two other scenes in the film in which we are able to see Alex's fantasies. One of these is in prison and in it he is flogging Christ, cutting throats in war, and being attended to by concubines. The other time is with the playing of the 9th's scherzo in his bedroom.

The twin lines of people applauding strikes me as curious enough that I figure why not look up the word "applaud". It comes from the Latin "plaudite", "to clap, applaud, approve", and as we see here is a response of approval, and one of course with which we're all familiar. And what is the word for the response of a disapproving audience? Explode. From the Latin "explodere", to drive out or off by clapping, hiss off, hoot off. It was originally theatrical, just as applaude, and in English later came to mean to "drive off with violence and sudden noise", then "to burst with destructive force".

With the first fantasy we see of Alex's, we have a lengthy sequence of the music animating the dance of Christ first. Only after this do we have insight into his imagination. We see a woman (a stuntman) in wedding white falling through the trap door of a gallows, which we imagine is a hanging but it is the non-hanging of Cat Ballou, unused footage from a film in which Cat Ballou has her Hollywood escape at the very last minute. Rather than being treated to rapes and killings, though we see Alex with bloodied vampiric fangs, we then have explosions. Because we have these two scenes in which we are able to view Alex's imaginings, and both orchestrated by his mind in response to Beethoven, I'm looking at them as being connected and that we can better understand one the other by comparing them.

Some are of the opinion that it's intended we believe Alex to be masturbating during the bedroom scene, orgasm being symbolized in the explosions, but the subtext of the fantasy explosions is instead, I believe, what it was originally theatrically.

Explode, 1530s, "to reject with scorn," from L. explodere "drive out or off by clapping, hiss off, hoot off," originally theatrical, "to drive an actor off the stage by making noise," hence "drive out, reject" (a sense surviving in an exploded theory), from ex- "out" (see ex-) + plaudere "to clap the hands, applaud," of uncertain origin. Athenian audiences were highly demonstrative. clapping and shouting approval, stamping, hissing, and hooting for disapproval. The Romans seem to have done likewise.

At the close of the performance of a comedy in the Roman theatre one of the actors dismissed the audience, with a request for their approbation, the expression being usually plaudite, vos plaudite, or vos valete et plaudite. [William Smith, "A First Latin Reading Book," 1890]

English used it to mean "drive out with violence and sudden noise" (1650s), later, "go off with a loud noise" (Amer.Eng. 1790); sense of "to burst with destructive force" is first recorded 1882; of population, 1959. Related: Exploded; exploding.

From the Online etymology Dictionary

My view is that the explosions in that earlier fantasy scene are rephrased here as approving applause. One thing seems quite unlike the other and yet they are related. Another reason I feel comfortable drawing a link between those explosions and the end applause, is the appearance of the woman in the dress of wedding white (Cat Ballou's stuntman) in the bedroom fantasy, and the end Victorian/Edwardian scene looking very much like a post wedding conjugal romp in a big bed of snow-like confetti. And, OK, yeah, its spiritually, psychically orgasmic.

The setting of this final scene and Alex's introductory expression suggest we look at the end of The Shining, Jack frozen in a mound of snow, a very similar expression on his face. It's confusing, is Alex surrounded by wedding confetti or snow? Whichever or both, Alex, frozen in his casts, frolicking in that snowy confetti bed of white, can be found in Jack frozen up to his armpits in snow, his eyes rolled back in the same expression that had come over him upon abandoning the wagon for a phantasmic hit of Jack Daniel which was so real it was as an eucharistic anamnesis event.

Alex is, I think, actually cured. His expression is deceptive, this isn't a violent scene. One could look on it as a spiritual transformation, male and female united.

Kubrick has rather set it up for the audience's interpretation of the end scene to reveal quite a bit about them and their reactions to violent as versus sexual imagery. The audience sees the crazed look cross Alex's face, his eyes rolling up, mouth twisting, and then see him frolicking nude with a willing woman, surrounded by applause. There's nothing violent to it, but the majority of the audience is likely to interpret this fantasy of sex before a Victorian/Edwardian audience as an indication of Alex's perverse nature back in full force.

Dušan Makavejev's 1965 film Man is Not a Bird

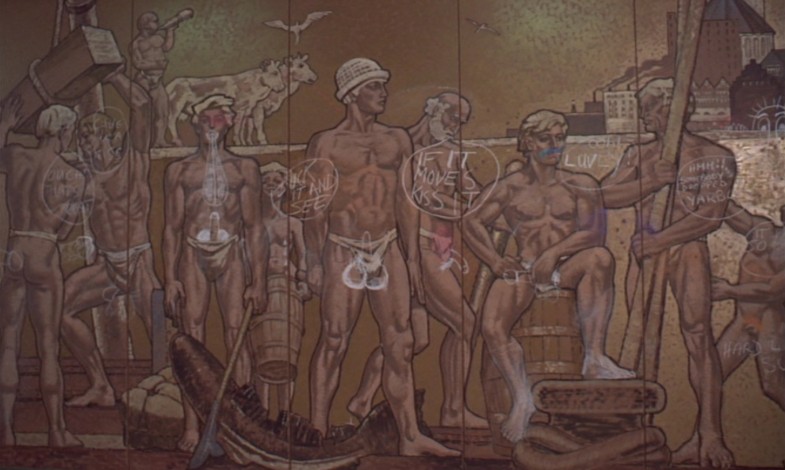

Now to look at a film I hadn't seen before 2019 and which I think was an influence on A Clockwork Orange. We will return to the communal entry wall of the building in which Alex's family lives, at 18-A Linear North, and the mural that is obviously government propaganda designed to extol the virtues of the working class, to the working class, as a means to cementing their position in and responsibility to the state through their acceptance of their situation and subjection to the class system. It isn't a mural in which the working class speaks of its own situation, instead it is intended to inform the working class that they are where they belong, that this is their value to society. The painting glorifies the labor of the worker with the antique glow of a golden age, just as we find the wall in Alex's apartment claustrophobically coated with gold paint. Those who recognize the truth of their oppression have defaced the mural, in which we observe dock workers backed by an industrial landscape. "Suck it and see" reads one word balloon.

Just prior this scene, after a night of rape and pillage, Alex and his droogs had stopped by a bar for their favorite mind-altering milk beverage, wherein they hear a woman singing the "Ode to Joy" portion of Beethoven's 9th Symphony. Alex describes the woman singing as being like a great bird having flown into the milk bar, the music having a profound effect on him, but inspiring violence rather than promoting the peace expected of the lyric, "Alle Menschen werden Brüder." But then this has been a problem with the 9th, which was inspired by the French Revolution, and was also used by Hitler--it is an exciting, stirring work, the grandeur of which can be used for good and for ill, the concept of what is a universal "brotherhood" being not, well, universal.

After Alex's Ludovico treatment, unable to act upon violent urges, Alex returns home to find he has been replaced. He goes to the riverfront, where we see a view of factories and smokestacks that reminds of the mural at the apartment building. We hear the seagulls that we'd viewed in the mural. The Dawn section from the William Tell Overture plays. The manner in which Alex gazes at the water, it's to be wondered if he is contemplating suicide. We learn that, unable to behave violently, means that Alex is also rendered helpless to protect himself. He has no choice but to be passive, the Christ who turns the other cheek.

Burgess is sometimes given as a socialist, but he was in fact a monarchist and believed socialism ridiculous, even leaving Britain in order to avoid paying high taxes on his wealth. He believed in wealth as good for its awakening and satisfying the senses. As for socialism and communism, he thought they were based on the "heresy" that man is good, can become better, and ultimately build a just society. Burgess instead held that man was born in original sin and is more likely to choose the bad. In one interview, conversation on his denunciation of humanism directly follows his statement that wealth is good and that he didn't begrudge the wealthy for their material comforts.

In A Clockwork Orange, the political picture Burgess presents appears to have Alex living in a socialist society, but if it is then it is a society that is highly classist regardless. A group that is against the Ludovico technique, which considers it to be state violence, is also influenced by Alex having previously harmed one of its members in a home invasion, and by means of effects of the Ludovico technique provokes Alex to attempt suicide, he flinging himself from a window. The supposed aim, that would deny any vengeance, is to vividly turn the public eye to Alex's treatment in sympathy with how he has been brutalized by the state, the Ludovico treatment leading to an act of suicide. Kubrick clearly presents the group in elitest terms, their privilege separating them from class struggle, most pointedly illustrating the author's hypocrisy with his wife functioning on as his servant.

Alex is, himself, no socialist. He's a petty tyrant, which is one reason he lands in prison. The mural backs a scene in which Alex's droogs rebel against how he had physically assaulted Dim while the worman was singing "Ode to Joy" at the milk bar. They insist that the power in the group be split between its members, rather than Alex always telling them what to do. They also have the feeling that Alex is keeping the bulk of the spoils to himself, and he probably is. Alex appears to submit but then later brutally seizes power over the group again. The droogs arrange for him to be seized by the police during a robbery that turns into a murder. Later, the droogs become police.

Now to skip over to Dušan Makavejev's 1965 film Man is Not a Bird. In it, an engineer, spurred by the government, for sake of an export deal, drives his fellow workers to finish a demanding job ahead of schedule, the installation of equipment at a factory. One can tell he knows this is wrong, but the idea is as it's for the communal good of the state they should be able to press themselves as hard as possible (a kind of self-sacrifice) and achieve this victory for the people. There is a certain amount of self pride involved for the engineer, and he receives a medal for his service at a big affair that celebrates not only the work but, supposedly, the worker.

What has this to do with A Clockwork Orange? The Makavegev film opens with a journalist calling in a report to his paper. We know it has to do with a performance of Beethoven's "Ode to Joy", and we hear how he first says the exalted words fell on the somber faces of the workers, and then he changes this to radiant faces. We have no idea what this has to do with until near the film's end. After this scene, the film goes to a flash back and will work its way back up to the present. Beyond the journalist, in the background, through a window, we see the smokestacks of the factory. As he speaks, the journalist moves to screen right and we see the exact same scene of the factory again but it is instead a giant photograph.

This, I think, must have been the initial inspiration for the mural in Alex's building that partly replicates the industrial waterfront of the Thames.

An important subplot to the Makavegev film concerns hypnosis. At the film's beginning, as the credits run, a hypnotist appears on screen, and makes "opening remarks".

A girl gell in love with a boy and couldn't live without him. Her parents forebade her to see him as the boy wasn't suitable for their family, and asked if I could help. I hypnotized the girl with her permission and asked why she ran after this boy. You see, a person under hypnosis tells all and keeps no secrets. She said he'd knotted together a hair from her head and one from his and placed them under her as she sat in a park.And that was that--she went crazy over him. I used indirect suggestion to free her of that delusion. They later thanked me and said the girl was finished with the boy.

He gives many more examples of superstitions, including those that are harming buildings and frescoes with people taking materials from them that they use in their folk cures. He finishes with saying,

So, you see some people are eating mortar, while others are preparing to fly to the moon. The moral is: Magic is absolute nonsense. You must fight it.

We later are shown his doing a demonstration of hypnosis with people taken from the audience, convincing them they are birds, lovers, cosmonauts floating free of gravity, and confronted with tigers and terrible, cold snakes.

A woman, whose husband is abusive, when another says it's all lies, disagrees. She says it's the same with the husband, great lord and master. That this is how they live. They believe everything. "He says to shut up and right away you shut up. And there you are, the man's got the power. You shut up and do everything he tells you. That's hypnosis. You look, but you've got no eyes. You go where his thoughts order you."

The other woman asks, "So what will you do now?"

The woman replies, "No more hypnosis."

We should be reminded of the newspaper headline, after Alex's release, that reads, "What will he do now?"

At the film's end we have a view of the factory with the voiceover of the hypnotist giving way to Beethoven's "Ode to Joy"".

I ask you to listen to my brief explanation so you won't go around saying that Roko uses accomplices, or evil spirts, or potions, or such. Hypnosis was already known to the ancient Romans, Egyptians, and Greeks. The word itself comes from the Greek hypnos, meaning sleep. But hypnosis is not ordinary sleep, but an induced sleep, artificial sleep. For a man asleep can do nothing, but under hypnosis he can carry out the most complex commands, including murder.

Dušan Makavejev's film is concerned with societal programming from top to bottom, throughout history, on all its levels, people not questioning why they act as they do, locked in place by a kind of mass hypnosis that denies free will.

As for the engineer, who is celebrated for his having finished the job ahead of schedule, and for twenty years of service, the event mounted is a performance of Beethoven's "Ode to Joy". We see a photographer taking shots of the event at the beginning of it, and I am reminded of the media rushing in to photograph Alex's reward of the sound system. The engineer is distracted. He had come to this factory for this job but also had become intensely involved in a romantic relationship. During the performance, the expression on the engineer's face betrays all he can think about is where is the young woman who says she has fallen in love with him despite his being old, who convinced him to fall in love with her, who he promised to take away from this dismal environment? The movie cuts back and forth between the performance and the woman making love to a young man in his truck, an individual who had been pursuing her and they have now gotten together while the engineer is at the celebration. Back and forth the film cuts, between the performance and their ecstacy, the "Ode to Joy" playing. It is this performance that the journalist was calling in his report about at the film's beginning, the one in which he altered his content from the truth, that the workers were somber, to instead saying they were radiant. The workers hadn't enjoyed the performance, they didn't appreciate the music that proclaims their brotherhood, they are disgruntled, and they didn't show up for a more personal celebration later for the engineer, they all instead went to the circus to see what was promised to them as "no illusions, truth plain and simple", a Snake Woman contorting her body into a circle, people with snakes crawling out of their mouths and twining about their heads, a high wire artist. The engineer--who had been hypnotized to slave as he had, pushing his workers to their limits, hypnotized as well to fall in love with a woman who had, for a time, hypnotized herself into falling in love with him, hoping he would marry her and take her away--dejected, disillusioned, at film's end is pictured wandering alone over scab lands down by a river that blazes with the reflected light of the sun.

This is where I think Kubrick got the idea for the worker's mural, impressed with its doppelganger function in the Makavegev movie, that the photograph so closely simulated reality that the viewer may be fooled for a second into thinking it was, too, a window, even though this was impossible as it was at a diagonal yet presenting the exact same scene. If accepted as "reality", it's an example of the kind of hypnosis that removes the ability to question. Also, I think Kubrick perhaps got from this film the idea for the headline, "What will he do now?", and for ending A Clockwork Orange as he did, Alex and the woman frolicking while Beethoven plays, photographers snapping away in his hospital room. Indeed, I imagine the headline, "What will he do now?", was added to cement his referring to Man is Not a Bird.

Recollect that I mentioned earlier in the analysis how Kubrick places Alex near where Antonioni filmed the party for Blow-up, where Thomas attempts to tell his manager what he has seen, but the manager is incapacitated by drink and drugs and unable to make any sense of it. At the end of that film, Thomas participates in an illusory, mimed tennis game that becomes auditory, real, and he vanishes.

A Clockwork Orange has less to do with Alex, his programming and reprogramming, than with an audience which has been repeatedly acknowledged throughout the film as participants. We can return to Killer's Kiss and see how Kubrick chose to import ideas of the magician's art, cinema interacting with stage and with audience, from the film Orson Welles did for Himberama. We can jump ahead to The Shining and see how Kubrick dissects the film and its set before our eyes and still the audience persists in their suspension of disbelief in pursuit of a coherent story. We can go to Eyes Wide Shut which questions what is dream and what is reality and decides life is a mix of both. What concerns Kubrick is the ability of the audience to cling to the story despite the insensibilities that threaten to corrupt a traditional storyline, that they submit themselves to being hypnotized by the unexamined, he exploring as well how certain stories and theatrics can disrupt the hypnosis.

Probably, then, the most critical few seconds of A Clockwork Orange is the footage of thousands of Nazis in a sort of mass hypnosis walking in goose step, parading for Hitler, and choosing to keep believing, to stay enthrall of murderous deception, at the expense of millions of lives.

How it All Plays Together

The essential dilemma, as with all Kubrick's films, is whether it is a free will universe for humans or a predetermined one into which the protagonist and all players fit into their allotted roles and pursue their lives believing themselves to be autonomous, free-thinking creatures. Problems enter when deja-vu creeps in, as again happens in all Kubrick's films, and old territory begins to be retrod. In the case of Alex, he is ready and willing to sacrifice some part of his free will for his get-out-of-prison-in-a-fortnight card. He may not believe that sacrifice will be absolutely effective, he may think that he might be able to slip-slide on the blurry edges and accidentally fall into delightful thuggery, not unlike a teen who never needs carry a sinful condom as their sex is always innocently accidental, but he is aware from the beginning he is giving up something and doesn't mind what until he's in the chair and learns he's lost Beethoven, but by then it's too late. He doesn't scream over the forfeiture of violence and sex, but he does over the estrangement from his beloved symphonies.

Some people lose it slightly if one even begins to suggest that Kubrick inclines the playing field to a slightly more difficult angle with plot points and symbols derived from antique and long-enduring stories, despite the fact Western culture is infused with the detritus of such things as the Greek and Egyptian sphinxes, tragic cult heroes like Oedipus, and the buggaboos that have driven various societies to believe that, hey, the gods will have our hides if we don't find a way to redeem ourselves for our crimes, even if the extent of one's sin is simply having had the mortal temerity to draw breath (and, really, who doesn't daily wish for some kind of redemption in their lives, a way to turn back time or excuse and cover over even the most minor of nagging actions and concerns that keep one from falling asleep). Maybe it is beyond the scope of their imagination that their world is actually constructed, every timber and nail and hewn stone, with meaning sluicing down the mixed cultural arteries from numerous ancient sources, the old symbols and stories remixed with the intervening generations but still very much concerned with the foundational questions that inspired them. This is the great garbage heap in which artists find the tools with which to ply their trade. Some fly by the seat of their pants and know-not-what-they-do but do it anyway. Others utilize those tools consciously.

But rather than further discuss Kubrick's use of myth and symbols and attempt to ferret out his personal thoughts upon them, which is impossible for me to do, it seems more prudent to discuss how all this plays together in respect to Kubrick's relationship to his audience.

The "how" of the manner in which Kubrick employees these tools is different from your straightforward retelling which may involve nothing more than dressing an old story up in modern clothes and updating the language with street slang. Actually, the "how" of his doing it is pretty damn intricate and fueled by ideas he played around with a long time, because he carries them from film to film, such as his concern with dualities that was expressed in his first movie with twins as subjects (you don't get much older than stories of divine twins and ancient dualities). Some people's imaginations only allow them to comprehend old stories and symbols as informing an artist's work if it's plainly stated on the cover. Suggest that a film has the hardware of myth and symbol in the screws and nails that hold the timbers of the stage together and they begin to be suspicious of over-rigging and/or the ability of any artist to handle the complex relationships of anything more intricate than a simple two by four lying in an open field. To explore visuals and musical choices as being more than emotional agitators and sensory snacks is alien to them as what isn't cleanly stated on the surface offends the law of paths of least resistance.

Kubrick employees all resources available to the cinema artist to relate a story--visuals, sound, choice dialogue--and he doesn't look upon that story as being a simple narrative. Perhaps one reason Kubrick has been thought of by many as a cold director is because those resources aren't devoted only to arousing different emotions. People try to psychoanalyse his work, and he really wasn't that interested in the psychology of a character informing all his or her actions. Psychoanalysis of fictional characters is pretty well impossible. Ask any honest artist and they'll tell you that, because they have made the characters up. They aren't real. You can't trace their behaviors and pathology back to some unknown root cause if that root cause is not overtly stated and a part of the story, because they aren't real people, and the audience has a tendency to really not well comprehend what this means. In Kubrick's case it means never supplying a back story for the characters because root cause for current behavior isn't to be found in the personal sphere. He knows that presentation is all and the audience is going to read a character's emotional state based on how he chooses to edit performance. Kubrick makes no pretense of his films being and encompassing biographies of his fictional characters. In place of personal back story for his characters, Kubrick creates stages filled with references and puzzles that are all to do with a kind of philosophical and conceptual back story driving the action, which plants the character in the universal rather than in the particulars of any unique place and time and circumstance having brewed them. You can't look to Alex's past and try to uncover if and how he might have been abused and how that motivates him. Instead, he and his context are a collection of myths and symbols and concepts. He breaks down their existing components to glyphs that become the supporting impetus for the overall narrative. We may not know exactly what he meant by the use of certain symbols and those components, but sometimes even the fairly obscure can be sensibly guessed at being used. There is no personal "Rosebud" for Alex. If there was a personal Rosebud then the character must always be a mystery as a fiction. Instead, Kubrick asks you to step back as far as the origin of the Ourobourus, Leviathan, and to attempt to comprehend archetypes as living forces that consume the narrative and transform it into a kind of real, living creature. This creature you can examine for discreet and hidden meanings and drives as, for instance, that which the myth of Leviathan describes is at least a real, clockwork function in the solar system that rules the solstices and equinoxes, and Kubrick's pyramids, trapezoids, vanishing points and single point photography are descriptive of a real but deceptive phenomena of perception.

Kubrick is also unconcerned with back stories for his characters as he is not at all interested in telling a standard story. He is instead concerned with how the story develops as a real dialogue, not a fiction, between what's on the screen and the audience member. He doesn't build in-depth relationships usually between his characters because he is instead constructing a relationship between them and the audience. He wants the audience to not relate to the character and its back story, to sympathize or empathize, but to instead be an active participant in as much as the concepts as living forces that consume the narrative and transform it into a living creature are thus in active dialogue with the audience. And the audience need not at all understand this intellectually, or what it means, because myths and symbols are ultimately indecipherable mystery stories. One may peel back different layers of meaning but none of those layers can give absolute insight to what is as mysterious as the blank walls which outline our mortality.

At least, that's how I've come to rationalize Kubrick's methodology.

Approx 12,900 words or 24 single-spaced pages. A 92 minute read at 130 wpm.

Go to Table of Contents of the analysis

Link to the main TOC page for all the analyses