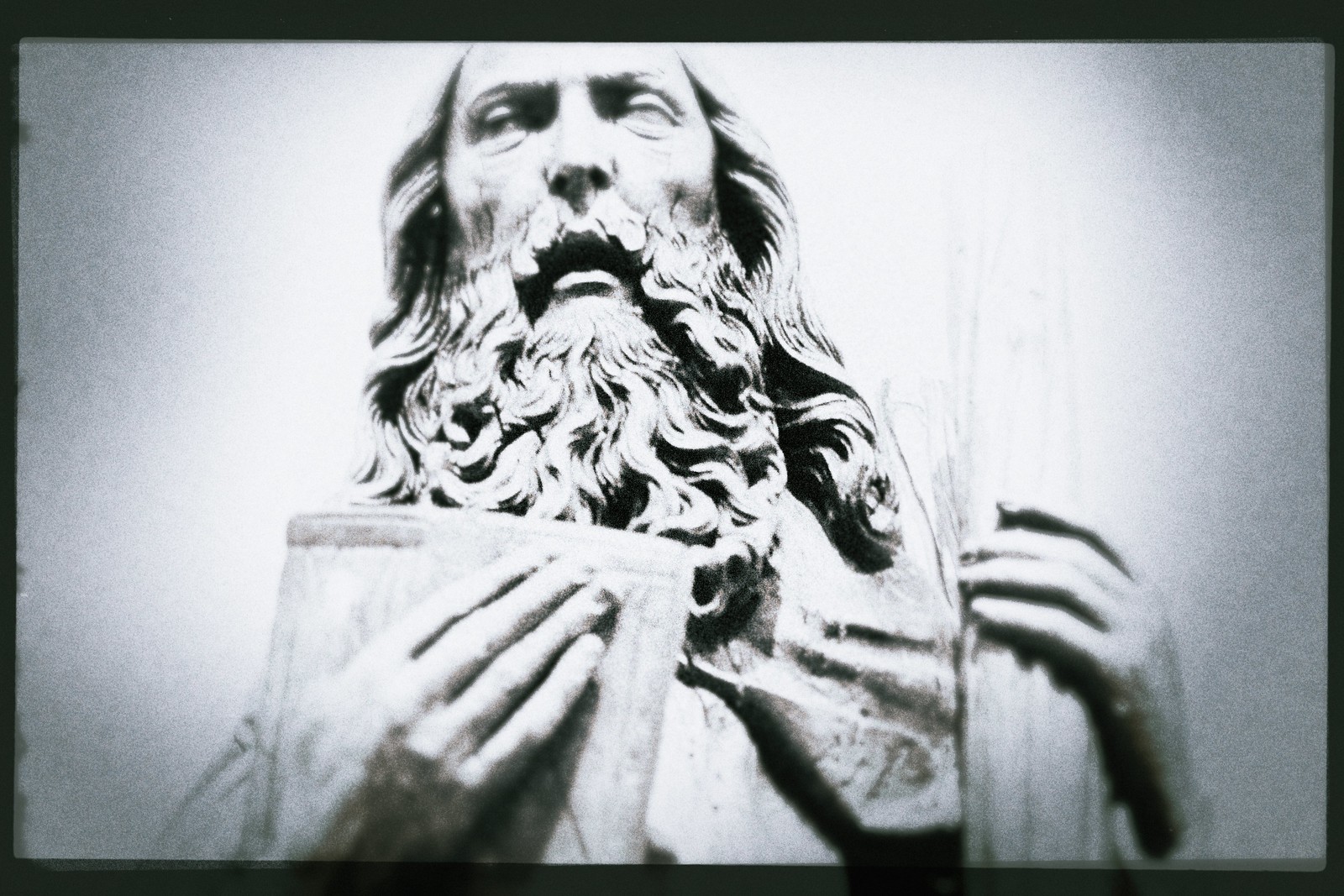

Portrait of "St. Andrew", Linden Wood Carving, ca. 1505, photo from 2015

img_1403a, 15_sept_IMG_1403

On the High Museum's website, the sculptor of the portrait of St. Andrew is given as the "Master of the Bibra Annunciation". Google Arts and Culture relates this is Tillman Riemenschneider, or the workshop of (research has determined it to be from his workshop), that the piece was donated to the High in 1958 by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation (Kress dime stores), and that research of the carving has focused on the "uncertain attribution" and the question as to whether the carving had been colored originally. The museum's website states at some point the figure was stained brown, simulating aged oak, but may have been originally painted in lifelike colors. They also have another work by the same, St. Elizabeth, which I've never seen and is beautiful. The question of whether or not "St. Andrew" was painted is significant as Riemenschneider was one of the first sculptors to not have all of his sculpture painted, whereas before this was the style. His work is described as in the late Gothic style, later showing mannerist characteristics (less focused on realism than pushing certain eccentricities of style), and because some of his wood pieces are not very well handled, it's believed he likely learned stone carving before turning to wood as well.

What is this about the "Master of the Bibra Annunciation"? In other words, this work is by the sculptor who carved also "The Annunciation" for the Bibra family. They were patrons of Riemenschneider, and according to Wikipedia were a leading Uradel (ancient noble) family in Franconia, the northern part of Bavaria, and Thuringia, from the mid 1400s to about 1600. "Later on the family rose from Reichsritter (Imperial Knights) to Reichsfreiherr (Barons of the Holy Roman Empire)".

Born in present-day Thuringia in 1495, Riemenschneider settled in Wurzburg in 1483, where he joined St. Luke's Guild of painters, sculptors, and glass workers. Upon marrying Anna Schmidt in 1485, a widow of a master goldsmith with three sons, with his newly acquired wealth he was able to move from his apprenticeship as a painter to a master craftsman, opening a workshop in his wife's home in Franziskanergasse. The considerable wealth and prestige he gained over the years was obliterated by the German Peasants' War of 1524-1525 when in 1525 he was among those of the town council members who refused the order of the Prince-Bishop of Wurzburg, Konrad von Thungen, to fight the peasants. After the peasant's army was destroyed (100,000 to 300,000 in total, about 8000 outside Wurzburg), and the town surrendered, Riemenschneider was imprisoned for two months, his career was ended, his status was leveled, he lost most of his property, and though a son, Jorg, continued his workshop after his death, Riemenschneider was forgotten.

100,000 to 300,000 killed. That's a lot of people. They weren't just killed, they were butchered. Descriptions of slaughter are near impossible to envision. Poor peasants and farmers, ill-armed with not much in the way of funds, no cavalry, gathered together democratically in the largest European revolt of the people before the French Revolution. Though some of the rhetoric of the revolt came from the Protestant Reformation, Martin Luther's schism with the Roman Church having occurred in 1521, four years after his publication of Ninety-five Theses, Luther was enough in the pocket of the elite that he believed the social system against which the peasants were rebelling was ordained by god, that the peasants had their place working the earth, the elite had their place keeping the peace, and when the peasants rebelled he advocated a swift suppression by the ruling class.

"[The peasants] must be sliced, choked, stabbed, secretly and publicly, by those who can, like one must kill a rabid dog."

Martin Luther by Lucas Cranach the Elder, 1533

That's brutal. That's fiery and fearful determination to maintain the status quo. Some criticized him afterward but Luther maintained his stance, though he allowed that the nobles were too severe in their suppression of the rebellion. One wonders what could be more severe than to be sliced, choked and stabbed like a rabid dog. Martin Luther was no friend of the working class.

But then, after his excommunication from the Catholic Church, Martin Luther was protected by the German princes, notably Frederick the III, Elector of Saxony from 1486 to 1525, 1525 being the year the Peasants' War ended, which was the year of his death.

When "St. Andrew" was carved, Riemenschneider was about 45, his downfall some 20 years in the future.

Did Riemenschneider expect the peasants to win? Did he anticipate they may lose and that he would suffer for his refusal to fight them? Was he a fervent believer in the revolt? The exact "why" of the Peasants' War is still argued, but the uprising wasn't only composed of peasants, it included what could be termed as the middle class that wanted to hold onto the prosperity they'd gained since the Black Death of the 14th century, the nobility grasping at this through high taxes. Riemenschneider may have been among those in revolt as he was part of this artisan middle class. He depended on the elite for their commissions, but he had property, land. He had a lot to lose if the Peasants' War failed, but a social revolution was worth the risk. As it turned out, the war was lost and Riemenschneider paid for it with such anonymity that his name was divorced from his work. He only regained fame in 1822 with the discovery of his gravestone. Three hundred years had to pass.

St. Andrew, whose name means "man", brother of Peter, both said to be apostles of Christ, Peter becoming the "rock upon which the church was founded, the Holy Roman Empire from which Martin Luther split, will be understood as carrying, in this sculpture, the distinctive cross upon which he was martyred, rather like the Vitruvian man pinned to the shape of a diagonal X, or saltire. The most salient point of his legend is that he refused martyrdom on a cross of the shape associated with Christ as he deemed himself unworthy of that honor, thus humility is his virtue. The book he carries represents a gospel. These are traditional attributes of his, as well as long hair and a beard, and a fishing net, for he was a fisherman, but this statue shows no net. All that is known about him is apocryphal, legends with certain facts agreed upon, concern over the apostles only beginning about the fourth century, and there being no contemporary accounts of him outside of the gospels. He is said to have been martyred at Patras during the time of Nero. He became the patron saint of singers, spinsters, maidens, fishmongers, fishermen, women wanting to be mothers, gout and sore throats. One can easily comprehend how those in the fishing industry might beg Andrew's intercession, but I don't know why his relationship to the throat, singers, and concerns of women.

I suggest viewing the sculpture at the below links to see how different my capture is from what the statue seems to initially present at eye level. At eye level, with his eye's downcast, not looking directly at one, his mouth hanging open, Andrew appears as a figure worn down by suffering, humbly shouldered. I remember approaching the statue from a number of angles until I decided on a close-up capture of his face from below, where the long-suffering Andrew, the crucified Andrew, looking down at us, meeting our gaze, gains something of the fervency of devotion usually equated with the old testament prophets. Or maybe he is only weary, his face etched with deep lines, toward the end of his life. He reminds me a little of Dreyer's "Joan of Arc", at least that's what I saw from below. It is from below that shadows capture his cheekbones as prominent, his cheeks as sunken, and we get the feel of waves of hair that might remind of the ocean, important to a port such as Patros where Poseidon, among others, was worshiped.

Ashley Laverock's 2012 research report on Tilman Riemenschneider notes that one of the things that most distinguishes a Riemenschneider [workshop] sculpture are the eyes.

As Baxandall notes, one can identify Riemenschneider works by the presence of the so-called "Riemenschneider eyes" which are large, down-turned and symmetrical. The lower lid is sharply marked and underscored by S-shaped grooves that vary in number according to age.

As was my instinct for the sculpture, which is why I photographed it as I did, Laverock's research notes that the sculpture was intended to be seen from below, for which reason the distortion of the upper head when looked at straight on, but it's also acknowledged to be intended to likely be seen from a distance, which means the considerable drama of the close-up experience of the face viewed from below would be lost.

Intended to be seen from below--which means a position of some intimacy. Such as, imagine one is in the church and standing directly under St. Andrew, begging his help, what is it one feels in the statue and sees in its gaze? In a museum, this is art, and removes the aspect of the sacred, of a true believer looking for St. Andrew in this representation of him. He is patriarchal, severe, a character that has known pain. To me, he looks like a saint that expects suffering and urges one to comprehend that suffering is life. At the end, as the sun descends, if you've lived true to yourself, expect still to suffer. The question that pestered me--was this aspect of Andrew a St. Paul? Did he demand suffering in the manner of the self-flagellants? I don't think so. I don't see St. Andrew leading self-flagellants down plague roads, inviting people to thrash themselves as in Bergman's The Seventh Seal. This depiction of St. Andrew by the "Master of the Bibra Annunciation" has a certain ambiguity so that it can transform from seeming severely, single-minded devotion to humbly philosophical.

The position of the cross to Andrew's side confused me, rather being in front, and the cross necessarily compressed as if to suit an essential narrow depth. The research determines that the sculpture would have only been viewed on three sides, not standing independently, and was likely a part of a larger body of work. The cross was placed as it was for conservation of space.

If the viewer is disappointed that the carving is either not of or exclusive to Riemenschneider's hand, we shouldn't be, as Laverocks's research paper relates features of the carving that enable this identification are that the face of Andrew is more expressive than is typical for Riemenschneider and the hair more three-dimensional. And the face and hair are beautiful.

A final detail on the sculpture, in Laverock's research, is its provenance, which is notable for it having been looted by the Nazis. Acquired, from an unnamed dealer, by Riemenschneider scholar Justus Bier, at an unspecified date, it was confiscated by the Nazis during he 1930s, Bier fleeing to the US in 1937. The carving was later purchased by the Hamburg Museum of Arts and Crafts at an auction in Hamburg, then returned to Bier after the war. He sold it to the Paul Drey Gallery in New York, then in 1955 it was acquired by Samuel H. Kress, the sculpture gifted three years later to the High.

The statue can be seen here in Google street view at the High, and also the photo of it on the High's website.

Written Feb 2020

Go to this gallery's index/description

Return to Photography Galleries