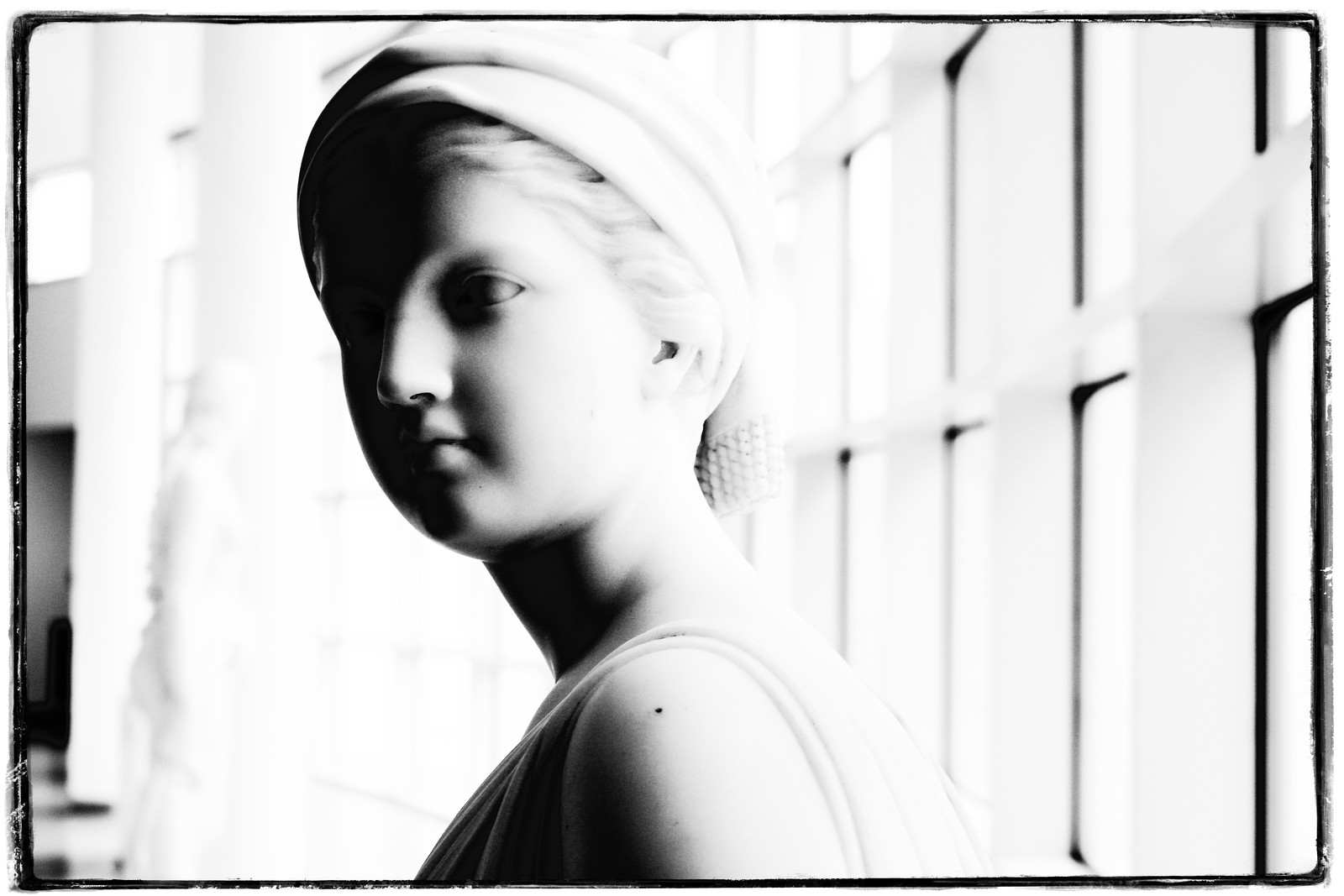

Portrait of Chauncey Bradley Ives' "Bust of Rebecca" of 1855. High Museum. Sept 2015

15_sept_IMG_1223

Charles Bradley Ives' full-figure "Rebecca at the Well", first sculpted in 1854, was so popular that 25 copies were made, and numerous bust versions sold as well. Striations in the marble will be different in each, and the bust of "Rebecca" at the High has relatively dark stripes on Rebecca's right cheek, which are obvious in my photos but not in the High's photo catalogue.

The Met Museum's page on their "Rebecca at the Well" erroneously states that "Rebecca was chosen to be the bride of Isaac, the son of Abraham, after offering him water from her pitcher drawn from a well." Instead, Abraham had entrusted a servant with the job of going to Abraham's homeland and selecting a bride for Isaac from among his relatives. The servant asked, should the woman be unwilling, if he should take Isaac to her (in order to convince her), and Abraham expressly said no, that Isaac was not to leave Canaan. He assured the servant that an Angel of the Lord was preceding him to ensure his endeavor would be a success, but if it wasn't then he would be released from his oath of finding the bride. So, the servant went, bearing many gifts for the prospective bride's family, and reached Nahor, Abraham's homeland, toward evening, which was the time when women visited the town's well. Stopping there, praying for god's help, he devised a test for Isaac's wife. He would ask for water, and the woman who also offered to water his camels would be the chosen one. A niece of Abraham's appeared, a virgin who was old enough to be married, and satisfied the test. The servant related his story to her family and the synchronicity (and wealth) satisfied them so that they approved the marriage. They wished to have Rebecca stay with them ten days before leaving for her new home, but the servant said he must leave immediately, to which Rebecca consented.

Another story of Rebecca that's prime for artistic expression is her aiding her son, Jacob, in deceiving Abraham and receiving the birthright blessing intended for his older twin, Esau. Before their birth, Rebecca had inquired of god, apparently by oracle, why they struggled within her, and was told this was the struggle of their two nations and that the elder would serve the younger, which was in conflict with the rule of inheritance. Jacob became Rebecca's favorite but then he was privileged by the oracle's promise, and when Abraham was near death Rebecca helped Jacob to camouflage himself so that he'd receive the blessing of the firstborn.

Rebecca's deceit is accepted as approved as it was god's will, but it remains a more difficult story ethically, alright for ancient, biblical times when oracle had god directly involved in issuing clear directives, but did the Victorians really want parlor art approaching such difficulties as a woman betraying an elderly husband who has poor eyesight?

Better to stick with the popular story of Rebecca at the well. Though the bible encouraged treating strangers well, with the story of Rebecca I don't believe that's the principle message. Rebecca, as represented by Ives, is obviously a child-woman, very young, her face much more child than adult. The full statue shows her as being possibly about twelve years of age, breasts just forming. I think we are supposed to ignore the fact that the servant obviously represents someone who is wealthy, having many camels. Instead, we are to think of Rebecca simply welcoming the stanger and going the extra step to tend his camels as well, attentive to their need. She is the picture of enthusiastic hospitality and kindness. She's good to animals. But we need to consider her in relationship to Ives' depiction of "Jephthah's Daughter". Under my photos of that statue I have already discussed how her story resembles that of Isaac's, only Isaac was saved from being sacrificed whereas Jephthah was not saved by a substitute ram and was compliant with her being sacrificed due her father's vow to god and was thus honored for this obedience. Her story resemble's Rebecca's, the wife of Isaac, in that they both involve oracle concerning a woman who first approaches. With Jephthah, he vowed to sacrifice the first living thing that emerged from his house upon his returning victorious from war. Jephthah's daughter only mourned because she would die a virgin, not having married, and she was given time to roam the hills for two months, with her friends, bewailing her dying a virgin. In the case of Rebecca, the honor of wife will be given the woman who gives water not only to the servant but the camels, and she is also the first woman that the servant encounters, but in this case she is receiving the husband deprived Jephthah's daughter. The story of the binding of Isaac and his replaced by a substitute is also connected with marriage, for immediately after this was when Abraham determined, Isaac being thirty-seven, that it was time he marry, and sent the servent to see a bride.

Just as obedient compliance is what is treasured of Jephthah's daughter in her submitting to being sacrificed, just as Abraham's obedience was tested but his son was saved, the lesson of Rebecca is likely obedience over kindness. She is so obedient that she does more than what is expected or asked of her, and then when her family wants her to stay with them for ten days before leaving she instead is obedient to the wishes of her new family that she depart immediately, to enter into a marriage with a man she has never met. Even the servant had believed it would be unlikely he would find a girl so agreeable, which is why he asked if he could return with Isaac. But the story of Rebecca at the Well is one of a girl-woman who does everything and more for others, and absolutely submits to her new family and husband. Some point out that the servant didn't ask to meet the most beautiful woman, prizing kindness over physical attributes, but, again, I think we're looking at a story extolling obedience, which actually needed to be immediately proven with Rebecca if she is to be forgiven for later deceiving her husband for sake of being obedient to an oracle of god. Jephthah's daughter, too, took so seriously Jephthah's vow to god that she didn't beg for him to break it.

Nicolas Poussin's painting of Rebecca at the well I think shows signs of cynism, at least among the audience in the painting observing Rebecca with the servant, for they are depicted as surrounded by the women of the village congregating around the well. All the women are well into adulthood, as is Rebecca a woman rather than a child, and in most artistic renderings of this story Rebecca is a young woman. Some of the women who stand to the side watching Rebecca's interaction have a kind of insouciance that might find them cynically considering Rebecca's compliance. One has to wonder if a few think Rebecca is so agreeable as she is obviously serving wealth and thus expects a significant award.

Whatever Ives would have been personally communicating with his Rebecca, I don't know. He chose to show her closer to childhood than adulthood, which is appropriate. I don't know if the Victorian audience found this startling or approved. Maybe there is a slight circumspection in her bearing, sometimes I instead see diligence. Striations of marble can often have little effect on a sculpture, but as these stripes cut down her forehead, over her eye, down her cheek, they give the impression that she has been slashed, which only in the photos might add some air of mystery. Her gaze is a complete blank, communicating nothing, revealing nothing of any inner feeling. She is a curious sculpture to photograph for this reason. She has no personality. Her direct gaze is almost as of one hypnotized, or an oracular well admitting the oblivion of an unknowable future, cause and consequence entirely dissociated from human endeavor and only a matter of the machine. She does not question, and perhaps that is the point. The servant arranges with god that the appropriate bride will act in a particular way, and she does so. She does not question. She does not question the synchronicity of her action. She does not question the marriage arrangement. She does not question the servant's demand to return to Isaac immediately. She does ask, when arriving at Abraham's home, and seeing the first man who approaches, "Who is that?" Then when told it is Issac, her husband, she veils herself. Much as her emotions are veiled here. Then she next questions why her twins war within her, and receiving an answer she works in the oracle's favor, unresisting. She is not as an Oedipus or other Greek characters who do all they can to defeat fate, to express their own will. Fate says, "This is how it will be" and she serves.

The High Museum's catalogue photo of "Rebecca"

My other photo of "Rebecca"

The bust of "Rebecca" was a gift of the West Foundation in honor of Gudmund Vigtel, director of the High Museum from 1963 thru 1991, and Michael E. Shapiro, director at the High Museum from 2000 to 2015.

Go to this gallery's index/description

Return to Photography Galleries