The Art - Photography

1970s Analogue Photography

Analogue black-and-white and hand-tinted photos

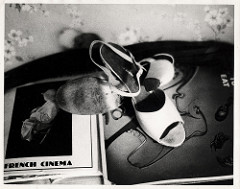

The earliest date I can fix for these photographs is about 1977, Marty and I were in college and living in our second apartment at 226 Broad Street in Augusta's Old Town (then just run down town), on the second floor above Mr. Baines, a retired taxi driver. Several of the photos are from that apartment, including the one looking over the rooftops. After that we moved into a nicer neighboring apartment, at 224 Broad Street, where I took the picture of the blinds in the bedroom, and the Hampton Grease Band "Music to Eat" album alongside the Cahiers du Cinema magazine, then over to a carriage house apartment on Heath Street, in the Sand Hills area, on Heath Street, next to the college, where the last photo date I can fix with certainty is 1979, when I captured the image of the movie theater where "The Hitter" was playing.

When Marty was briefly working at a photo equipment store, we managed to get some good deals and purchased a decent, used 8 mm cinema camera, a used Nikkormat still camera (budget Nikon), and an enlarger. The 8 mm movie camera was purchased on the maybe hope that I might one day get enough money to buy celluloid and an editor and make films on my own as I'd not been able to get up to NYU film school, but that never materialized. It was far too expensive. But for the time being we were briefly in a position where we could afford darkroom chemicals and film for the still camera, and appreciating photography as art, I started doing photographs. Photography was certainly not a new art but in the 1970s many stil didn't think of it as art. There still remains, with some, a peculiar prejudice against it, and now against computer art. I viewed art as a matter of intention and what one did and photography was just another medium for it, just as I would later view digital art.

What you are around as a child does make a difference in priming a person for possible futures, and that means access to the arts. They say, because of education and money, the middle class is the breeding ground for the arts, and I would seem to fit that bill as my father was the first in his family to attend and graduate from university, but I also came from a family that had no appreciation for the arts, and money was never made available for me to put into art. i had never had access to a camera as a child or teenager as our family was so disinterested they didn't do anything but the essential instant Kodak moments, maybe three blurry photos at Christmas, a photo of Easter baskets lined up on a formica-topped table, and those not even every year. When I was very young, I would be the one holding the camera as I was the one who sensed or cared how to frame an image, but by the time I was nine or so, even younger, there were almost no photographs taken and tossed into the single cardboard photo box stored away in the bedroom closet of my parents. A reason is we had no memories we wanted to record as we didn't make good memories. We never did anything and my parents had no appreciation for anything aesthetically, not even a simple flower, or a tree. My parents were not even vaguely astonished if I might pause to appreciate the beauty of a landscape because they were so unimpressed they couldn't fathom it, entirely without interest in the world around them. I'm quite literal when I say that not a single sunset was noted and sighed over as beautiful. Aside from my mother, who had studied piano, having a fascination with Papa Brahms (she believed they were spiritually bound together, he was sacred to her, and I'm not going to mock that fixation as it was so essential to her being), not only did they not acknowledge the arts, they had no appreciation for anything except alcohol and my parents ruled out as a place to be any place that didn't have a bar, so just as it was inconceivable we might ever visit a museum, it was as inconceivable we might ever take a trip to a State or National Park to stand in awe of the beauty of nature. The only images that ever hung from walls in our various homes were, for a couple of years, two very 1960s mass-produced prints on tiles of famed European landmarks that went in the kitchen, and one framed painting on silk of a pagoda before Mount Fuji, the latter because it was given my mother but a suitor she'd turned down, and I think it only ever went up on the wall in the living rooms of the six places I remember living in so she could tell the story attached to it, that she had been seriously courted by the red-headed rich boy with the bright red convertible and rejected him in favor of my scientist father who was her vision of romantically dark and handsome. We didn't have the usual subscriptions to photo-rich magazines like Life or Look or National Geographic. The only art book we ever had in the home was courtesy a science conference in Japan my father had attended in the 1960s, each attendee gifted with a slim volume of lovely, artistic photos--Impressions of Japan, with photos by Takeji Iwamiya--that showcased various aspects of Japanese culture, a book with which I spent many hours when I was growing up because it was a special window for me on art as a way of life and how even a single pebble could become a subject for consideration (influential enough that when I started photography, drawing upon memories of the photos in that book, one of my first staged photos would be of a black "stone" from a Japanese Go game). Nor did my parents conceive of any of the commercial arts as a potential career for anyone even outside the family; those were realms that simply didn't exist. As I grew older and became aware of people whose families had pursued any of the arts at even a hobby level, such as taking photographs--who had any hobbies for that matter--it was like brushing up against something very mysterious and foreign. My mother drank and abused me, and when my father came home at night he drank and abused me, and then they sat and watched bad television while they drank some more, and for most of my childhood years that is really all I knew about life, that was all living was, being in pain, desperately trying to escape pain, and anxiously waiting for the next session of pain. In the lives of my parents, they were the only people who mattered in the world; I only existed to do chores, babysit, and be the scapegoat. My experiences of the surrounding world were radically limited, even with food. As a teen when I began having occasional opportunities to socialise a little, friends and acquaintances would be astonished at all the things I'd never tasted. For years my husband's mother would sometimes bring up how amused they were at my response when they'd purchased me a pomegranate, how I had marveled over it--and I remember it as well, this fantastic subject of myth finally in my hands. I felt as though I had been gifted with an ancient treasure.

Despite the fact I lived in an art desert, from early childhood, on my own, I pursued writing and art, my way of speaking with the world and letting myself be known to it, that I existed and observed, that I was a part of it and it was a part of me. But it would never have occurred to me to even think of still photography--and certainly not cinema--because those demanded a camera, and cameras belonged to an unapproachable world. Cameras were near mystical with the mechanics of their capturing of light and an unimaginable acquisition considering the costs involved. Then I left home and I began to realize it was possible for me to do things, or at least dream of doing them.

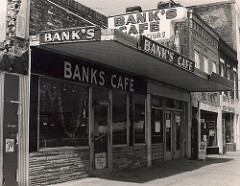

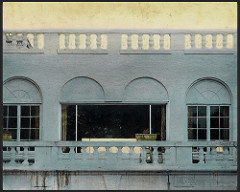

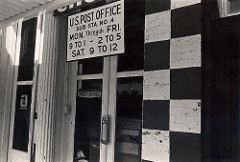

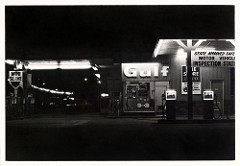

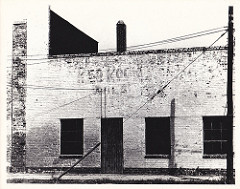

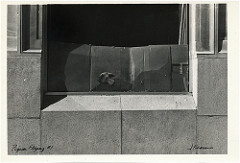

One would never guess, I suppose, from my initial portfolio of still photography, that my first effort in celluloid had been a surrealist film. Because I felt I needed cinema for relating a complex story, and because I had painting as a medium for non-realistic subjects. with still photography I concentrated on depicting what was in front of me. Having turned to still photography after being unable to get up to NYU film school, strongly influenced by Michelangelo Antonioni, my instincts were to go for things architectural, one of my favorite early photos being a very grainy, atmospheric diptych of a balustrade of the Bon Air. But such shots weren't appreciated and only seemed to confuse people as they imagined they didn't display technique. I turned to archiving the area's old buildings in a way that was one step rather than three steps askew from the straight-forward portrait shot. I favored details. I liked gas stations at night, yet satisfied myself with only one example of such as I didn't want to waste precious film and give gas stations an outsized place in the portfolio I was building. I rarely photographed humans but when I did I preferred something like a shot I took of Marty reflected in the window of a pawn shop. But I was also just starting out and trying to learn something about craft first, film and paper costing money, and so I was rather conservative with my subjects as I explored mechanics and film stocks and paper. I'm shocked now by how few shots I would take of a subject. Not wanting to waste film, I got my framing, and took one shot and no more if I was confident in it, maybe three at the most if I was exploring shutter speed and aperture. And I was thinking this was something I could turn into a career, doing professional, commercial photography parallel to my exploring photography as art. Marty had also become interested in photography, though not dedicated, his pursuit being music. He worked for a while developing film in the dark room at the newspaper, coming by the job as a friend of his was a photographer at the paper, but I knew I could never got a job like that, they wouldn't hire a woman. Marty had even picked up the random, commercial photography job, but no one was interested in independently hiring me to take photos of bike safety. Though he had only worked developing film, and selling cameras, even work such as that gave Marty photography-associated credentials that I didn't possess. However, there was a photography studio in town that was well respected, that did all kinds of work, in studio and in the field, was even nationally renowned for its photography of the Masters Golf Tournament, and I put together a portfolio (including many of the shots here) when I was 20 to 21 years of age with the idea of going down and applying for a position as an intern. I wanted to expand my knowledge and be in a position where I could learn about using different cameras, about photographing with lights, and about dealing with humans as subjects. That photography studio did everything, and so I didn't feel like taking in a portfolio of detail, street, and architectural shots was too limited. I believed my photos showed good composition and understanding of gray scale. I thought they showed that I cared about these subjects and strived to both bestow and capture personality. And what, I imagined, mattered more than showing one cared?

I arranged an appointment and in I went in with my portfolio, already an acquaintance of the family of photographers who ran the business, so I wasn't absolutely cold in that they knew my face. To some extent, our interests had led to our bumping into one another since I had been out of high school, and even before then as one of them had dated a girl I'd known. Though we'd scarcely even been acquaintances, at times I felt they somehow knew more than my face, such as when we were at some academic party associated with the college, they'd learned I was getting married, and one of them had spoken up and expressed his two cents, announcing in front of everyone that not only did they think I was too young to be marrying, they thought I was marrying the wrong person as (paraphrasing) I didn't display the expected romantic ardor in public, which had startled me that he'd have any opinion at all, and especially about people they didn't know. And even had they known I was a very private person who had never done public displays of affection because I had history that made for my own style of boundaries, that was outrageous and unacceptable on their part. I wondered, "What's it any of your business? Do you think you'd have a chance with me?" It was odd. I find this is actually embarrassing to relate, and you are perhaps thinking now, "And you went to them looking for an internship? What's wrong with you?" But that was a few years past. They had been around some when I was working on a documentary film on the Savannah River as part of a course in college and relations between us seemed to be fine. They knew I'd had aspirations to go into film, that I had taken up photography, we were aware of one another. It was a small city, small pools. You do what you can with your small pools because that's all there is. Theirs was the photo studio in town and though it was a family enterprise they had a number of people working for them from outside the family. It was a legitimate step to try to take. I imagined that, though I'd been unable to go, the fact that I'd been accepted at NYU's film school would run strongly in my favor. It showed that people beyond our pool had believed I showed promise.

No, I didn't think my photos were exceptional. I was new at this. I had books at home filled with exceptional photography created over the lifetimes of various artists, many of whom had also done commercial work. But I hoped they would see I had potential, and that I would be able to learn and become a respectable photographer through an opportunity to work in the studio and in the field. They opened my portfolio, glanced through my photos, then said, "You will never be a photographer." How many times now had I heard this before? "You will never..." But I felt the photos must show some commercial promise. I didn't understand the absoluteness of the rejection. I asked why, what could they tell, looking at my photographs, what assured them I would never be a photographer to the degree that they wouldn't even take me on as an intern and that they would say "never". The announcement that I would never be a photographer was amended to my showing (paraphrasing) an artist's eye and they could tell from these I would never learn how to be a photographer. I tried to convince them otherwise. I said that was why I wanted the opportunity to intern, so I could gain experience, so I could learn. The response was a definite no, it being added that they could tell I didn't have the right personality either. They said the right personality and the photographer's eye couldn't be learned, and polished it off with making it clear to me I had no future in photography, so there was no reason for me to work further on my portfolio and return. I was told they seriously doubted anyone else would have me either. And with that I was dismissed, the feeling communicated that I had not only overstayed my welcome but had displayed unacceptable temerity by asking for an interview at all.

One might ask, would they have taken a woman on as an intern--not ever, but at that time? I don't know if my being a woman had anything to do with it. Marty has assured me it did. But I was one of those people who didn't like to think I might be discriminated against because I was a woman. Even when I knew I was discriminated against because I was a woman, I didn't like to think it was because I was a woman.

The rejection was profound enough, solid enough, with no words of hope, no appreciation at all for anything in the portfolio, no encouragement, that I took it for fact I had no future in photography and never showed my portfolio again. There was apparently no point. My photos felt dead now. What my eye valued, others did not, and I was incapable of defining why this was so. Soon, the price of silver soared and so did the price of photography, my second-hand camera broke, and I ran out of any funds for pursuing photography. After we moved to Atlanta, for rent, we sold the enlarger, our dark room equipment, and the movie camera. I threw away all my negatives I'd amassed through my explorations of, especially, Augusta's old town and downtown, which had been difficult for me to photograph as a woman, the areas then largely abandoned but for bars and strip joints that serviced military. When we lived in old town, more than once, on my way home from photographing buildings, soldiers would follow me even into the residential area, yelling sexual threats, and I had to take an extra hour walking circles around blocks in order to lose them and keep them from seeing where I lived.

Jump many years to the introduction of the DSLR and Photoshop. I took up photography again. I actually don't qualify myself as a photographer. I have never had expensive cameras and lenses. I qualify myself as an artist who takes photos. I like to sometimes think that something among them has value. I've tried to make it so. In retrospect, I do believe, had I been given the opportunity to intern, I would have proven to be a good photographer, that I would have been able to make a career out of it, but it wasn't to be. Because, at the time, I really did imagine the studio must be right, that I had no future in it, and that what I saw as beautiful and worthy in my photos must be confined only to my eye.

I've put up my old photos of Augusta with the knowledge that there are buildings that have been torn down, places that have dramatically changed, so that they are now a time capsule and perhaps a few have value for that reason.