EIGHT

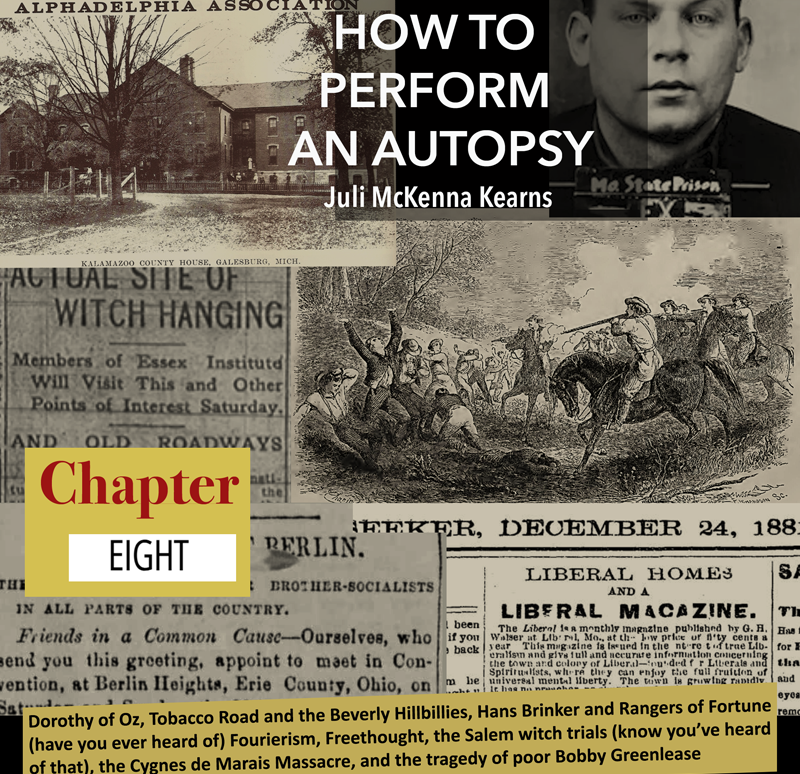

Dorothy of Oz, Tobacco Road and the Beverly Hillbillies, Hans Brinker and Rangers of Fortune, (have you ever heard of) Fourierism, Freethought, the Salem witch trials (know you’ve heard of that), the Cygnes de Marais Massacre and poor Bobby Greenlease

1

Because of Dorothy of Kansas who, with Toto too, tripped to Oz in the swirling, whirling vortex of a tornado (called a cyclone in Frank Baum’s book, I was taught to call the North American phenomena a tornado, having learned as a child that cyclones have to do with tropical areas out past the west coast of America in the Pacific Ocean, that’s where one encounters cyclones, which form over water), for me to have been born in Kansas to a woman named Dorothy, and both my grandmothers named Dorothy, for which reason my mother went by her middle name as her mother was the Dorothy in her family (no nicknames like Dot or Dottie) always struck me as a minor joke neither funny nor bad enough to elicit a modest laugh, but I was amused. Also, it seemed to me there might be a connection between the book and the proliferation of Dorothys. Time now to finally look it up, and I find that Dorothy had not figured in the top 126 U.S. girl names in 1880-1890, then in the decade following 1900, the year The Wizard of Oz was published, Dorothy jumped from fifty-seventh place to seventh (the decade in which my grandmothers were born), then in 1910 to 1919 it moved from seventh place to third, from 1920 to 1929 it was a second place name, moved down to sixth in 1930 to 1939 (the decade in which my mother was born), then after 1939, the year The Wizard of Oz sprang up out of the book, transformed into a Hollywood musical and sang and danced down the yellow brick road on movie screens around the globe, Dorothy fell off the Top 10 chart forever, or at least to the present day, despite the fact The Wizard of Oz was infinitely better as a musical, despite Dorothy’s heartfelt encouragement that somewhere over the rainbow bluebirds fly and troubles melt like lemon drops, because there were too many Dorothys, the U.S. was saturated with them, it had its fill of Dorothy and was canceling the name, except for a woman named Judy who, in blue-and-white checked pinafore, her shoes each shimmering with 2300 ruby red sparkling sequins, would become as a monument to all Dorothys, whether they liked it or not. Both of them born in Missouri, though about 275 miles apart, my mother’s mother in north-central Missouri and my father’s mother in the southwest, my grandmothers would have shivered their shoulders and shaken their heads dismissively if I had ever brought up The Wizard of Oz to them, they would have been offended by the indignity of their names so famously usurped by a children’s book then Hollywood. I did bring this up to my father’s mother and she frowned and wrinkled her nose in the way that let me know I was not to bring this up to her ever again. They were serious adult Dorothys who consumed their television with a mixed drink. Neither of them had anything to do with the choice of their names, their parents instead were the ones who tagged

Eight - 2

into the trend. None of us have anything to do with names given us at birth that become a part of our identity, the familial and cultural baggage they a priori import into their relationship with us, as if we might be thus intrinsically known by a name, like some might hope to describe a person’s psychology by the shape of a nose, the height and breadth of a forehead. Our names are more often than not bestowed on us by our parents and ultimately refer to them, which is perhaps the point. Do we each of us labor to make our names belong to us, rather than we belonging to our names, consciously or unconsciously? Our names can be so much a part of us that they are as our skin, and for some they wear just right, while for others their names are such a deformation of their essential beings that they legally change them in adamant protest. “No, that’s not me.” The responsibility of bestowing a name on someone is perhaps not taken seriously enough. People keep dropping on us names with which we have nothing to do and we may feel we must bear them as an anointing from Mother and Father Cosmos. Many acquire a nickname, but it may be unsatisfying, perhaps especially if assumed while one is a child, it may feel infantilizing, or it may be even derogatory. My spouse’s mother’s paternal line received not only official given names, first and middle and surname, but also an unofficial name by which they were known by family and friends, so that a person named Ezra William Last Name would instead be called Jodi, and Desera Wilber Last Name was known as George. There are cultures in which, as one becomes older, second and even third names are given, or chosen by the individual. Had I remained in the Roman Catholic Church or the Episcopalian, eventually I might have received another name had I elected to go through the process of confirmation. When one is baptized as a child, one is brought into the church’s body by one’s parents, and godparents are chosen who are supposed to guide and support the child on their Christian road. When one is confirmed, one is personally electing to reaffirm one’s attachment to the church as an adult, on their own two feet now, often in adolescence, about the age of thirteen, which is too young for a true personal assessment of what one has been taught about God and the universe but the right age to be convinced everything is just as one’s been told and that confirmation is the natural conclusion. But I was never confirmed as the wheels for that were never set into motion and I never initiated them as I had no desire to be confirmed, it was meaningless to me. Somehow my siblings were confirmed but I was not, and when I was sixteen or seventeen I was ejected from the church as a heretic.

In case one isn’t familiar, the reason one takes a saint’s name is you decide upon which saint you’d like to emulate, who has virtues that resonate with you, some holding the belief this saint will intercede for you with a very-distant-God, they are your personal patron if you are Roman Catholic, whereas if you’re Episcopalian the saints are just members of the body known as the communion of saints, which is all the believers in Christ, including you, but they have been formally recognized as better than you. As for what makes a saint, in the Roman Catholic Church the candidate for sainthood has to perform at least two miracles post-death in order to be canonized and get their own medals and recognition on the church calendar, while in the Episcopal Church, which started out with many of the pre-Reformation Roman Catholic saints, one just has to be exceptionally good in some way, you are an example of life lived in a holy manner, like Saint Sarah Hale who is responsible for the rhyme “Mary Had a Little Lamb”. She’s a saint because she is credited with laboring hard to

Eight - 3

make Thanksgiving a national American holiday. Harriet Tubman, who made thirteen trips to lead slaves to freedom is an Episcopal saint, and abolitionist Frederick Douglass and Dr. Martin Luther King are also among the Episcopalian Black saints, all good people to emulate. Among the few Episcopal American Indian saints is Enmegahbowh, an Ojibwe Episcopal missionary. The Roman Catholic Church has over 10,000 saints while the Episcopal Church has I don’t know how many and I’m not going to find a listing of all the Roman Catholic saints either. Excluding the Virgin Mary, the Vatican website sells medals of St. Francis of Assisi, St. Benedict, St. Patrick, St. Peregrine, St. Gerard Majella, St. John the Baptist, St. Stephen, St. Thomas the Apostle, St. Peter, St. Barbara, St. Agate, St. Nicholas, St. John Bosco, St. Matthew, St. Andrew the Apostle, St. Jude, St. Mark the Evangelist., St. Escriva, St. George, St. Rosalia, St. Paul, St. Rita of Cascia, St. Therese of Lisieux, St. Clare, St. Joseph, St. Anthony, St. Christopher, Archangel St. Raphael, Archangel St. Michael, for some reason there’s no Archangel St. Gabriel medal listed. I’m looking at a website that sells votive saint candles that look like designer candles.

Saints make money. They are a business.

The Harry Potter book universe didn’t work the same magic for the name Harry as Oz did for Dorothy of Kansas. In the United States, Harry was in the top ten from 1888 to 1894, never rising above the position of eighth place, was in the top twenty from 1895 to 1916, then went on a steady downward slide so that by 1957 it was no longer in the top 100 and in 2018 was positioned at 620. In the United States, the name Harry wasn’t rescued by either Harry Potter or American Anglophiles who might have been influenced by the birth of Britain’s royal prince Harry (however, a nickname for Harold) in 1984. The Dorothy that was my mother’s mother was married to a Harry, not a Harold, at least his middle name was Harry, a name he received in 1900 while Harry was in the top twenty and I don’t even know what anyone called him outside the family because my mother only called him “Daddy”, her mother only called him “Daddy” and “Mac”, it was our duty to call him “Grandpappa”, and my father only called him “Mac” if he called him anything. So, maybe he was called “Mac” by everyone except for those who called him “Mr”.

When I, as an adult, visited Sedan, Kansas, county seat to Chautauqua County, Kansas, home to several generations of my father's father’s line, my hope being to dig up a little sound information on my elusive family, I found that one of the town’s attempts to pull in tourism had been to wrap around the downtown Main Street area the longest Wizard of Oz yellow brick sidewalk of a path in America. Not so much a yellow path, a little less gray than the sidewalk in which it’s embedded, over 11,500 bricks have been inscribed with the names of people from around the world who have donated to the cause. If you're so inclined you can probably still donate one, and you will be confident your brick is a good thing as the project has the Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval. “We test it, so you can trust it,” Good Housekeeping avers, which means if you donate money for a brick it will be formed and baked and placed in the ground and you’ll be remembered in Sedan for however long the not-so-yellow brick path sidewalk lasts, or whomever’s name you have inscribed on the brick, which was a point of the project, to use the proceeds to fix and maintain the town’s sidewalks.

Eight - 4

Some parts of my paternal family arrived in the area in the early 1870s, before what was Howard County (named for General Oliver Howard, a Union officer at Bull Run) would be renamed and divided into Elk (the Elk River runs through it, maybe there were a lot of elk around) and Chautauqua Counties (named for Chautauqua County, New York) in 1875. A little over 11,000 people resided in Chautauqua County in 1880, now there are a little under 3400. The population of Sedan (named for Sedan, France, which a native from Sedan, France, thought it looked like and it kind of does but wilder) is now about 1000, which is near what it was in 1900. As of the 2000 census, less than one percent of the population was black, about ninety-four percent was white, and only about three and a half percent was indigenous, despite bordering both the Osage and Kaw Reservations. I imagine it wasn’t far different in 1900 though my family was often living amongst Osage “half-breeds” who often identified themselves as white when not living on Osage lands but were identified as Osage on the federal census when living on the reservation. To the east, Montgomery County had about 18,000 people in 1880 and in 2020 had 31,000. To the west, Cowley County had about 21,000 people in 1880 and in 2020 had about 34,000. To the south, Osage County, Oklahoma, had about 20,000 people in 1910 and in 2020 had about 45,000. To the north, Elk County, Chautauqua’s other half of the Howard County of which the two were formed, had about 10,600 people in 1880 and 2400 in 2020. While the surrounding counties increased in population, with the exception of its twin to the north, from 1920 on the life’s blood of its future was either suctioned out of Chautauqua County, or fled, or both, my grandfather included and both of his siblings, they all left. Though my father’s father circulated around Chautauqua County, never moving far from it, engaged with family who remained, he and his sisters had absented the adopted home of their predecessors, and their children and grandchildren would not return. The top contributor to Chautauqua County’s economy is currently beef cattle ranching and farming. Seventy-eight percent of its farmland was used for pasture in 2017, and sixty-seven percent of its sales were almost all cattle and calves. Maybe Chautauqua County decided it just didn’t need many people hanging around because it belonged to cows.

Many relations were ranch hands, but if my grandfather was ever a ranch hand, he never mentioned it. He did have a horse as a youth, I don’t know what color or type, but I never thought of him as a horse person or having been one in the past, though the way he brought up the horse I knew this was a significant feature of his childhood, that he was proud of having had a horse. I have the feeling that after going off to high school, once out of the daily saddle he may have never gotten back in it. From the way he told his story of having had a horse, I don’t believe his two sisters would have been given horses as well, but I could be wrong on this. My cousins on my father’s side, with whom I’ve no contact (no contact with any cousins), some of them became horse people. I’ve no clue if my father ever sat in a saddle.

The Chautauqua County courthouse is two stories of 1918 red brick set upon a bottom story of limestone, a portico staged with four Ionic columns embellishing the front entrance. The slender Ionic columns, these without flutes, each has a capital composed of volutes or scrolls, which is the ornament said to form the basis of the Ionic order. The embellishments are however decidedly middle American, the

Eight - 5

dressing up dressed down enough that you will not forget you are in a small town in southern Kansas and mistake yourself for being in the Mediterranean that delights with olives and azure seas. George Putnam Washburn, eventually George Putnam Washburn and Son, was the architect for the Kansas State Board of Charities, and designed thirteen courthouses across the state, dipping down into Oklahoma for at least one, and glancing around at them I’m surprised that I find the courthouse in Chautauqua, exceptional for its flat roof, the most pleasing in its confident neoclassical revival simplicity. That flat roof, a rarity for Washburn, really does something for the building’s bona fides. Set into the “basement” or first story limestone is a ceremonial marble cornerstone that on one side gives the names of those associated with the design and construction of the building, on the neighboring side of the cornerstone the engraving informs it was laid by Vesper Lodge No. 136, A.F.A.M., A.L. 5917 to A.D. 1917. The A.F.A.M. means Ancient Free and Accepted Masons. The Symbolic Lodge uses a reckoning of time called Anno Lucis, “in the year of Light”, that fixes The Beginning at 4000 years before the Common Era thus A.L. 5917. This was calculated by the Masoretic text and was a date supported by Isaac Newton, who contemplated an apple’s fall and came up with gravity as a force of nature but was about 13.7 billion years shy on the age of the universe, however I don’t know if he personally held the belief the universe was only as old as that set in the Masoretic text or if he was only stating this was the Masoretic text’s calculation. A Standard History of Kansas and Kansans, published 1918, gives a Dr. George Jack as a member of Sedan’s Vesper Lodge remembered in the cornerstone of the courthouse. Dr. Jack would have been a member at the time the cornerstone was laid. His name is familiar to me through his marriage to Ermie, a daughter of relation Martha “Mattie” Crockett. A physician, Dr. Jack served as county coroner and was on the board of education. His father-in-law, William Lemmon, who made it into William G. Cutler’s History of the State of Kansas, published in 1883, was an attorney and register of deeds in Chautauqua. None of my direct line was so notable as to make it into either book, and for some reason only my paternal family’s Crockett side made it into The History of Chautauqua County, Kansas, Volume I, published 1987, which gave them as having been there five generations, but the cemeteries of Chautauqua hold other lines of family who made their mark on that prairie in some way or another for a century, some dying after only a few hours, and some producing descendants who were bound to eventually leave and not donate to the land the testament of their bones.

The choice to have the facade of the courthouse ornamented with Ionic columns perhaps refers to one of the three pillars of Freemasonry being the Ionic which is connected with wisdom and is the Master’s pillar. If you were aware of this then as you approached the building you could assure yourself that beyond those Ionic columns wisdom would prevail, yet one knows there are going to have been more than a few who were justifiably upset with rulings handed down within.

I climbed the outer then inner stairs of the courthouse to reach the appropriate office, accompanied by husband and child (who was enthusiastic for the adventure), looked for possible angles wanting a photo taken but the building’s interior resisted my eye, and met more resistance at a nondescript counter where I lodged my request for family wills. Though several lines of my paternal family had lived in Chautauqua

Eight - 6

County, I’d already found the few people I encountered in this conspicuously underpopulated town were unfamiliar with any of the primary family names I mentioned, not that I expected anyone to remember them but a small part of me hoped there might be a small reciprocity between a town member and a person whose family had lived there for over a century, but the woman who assisted me in looking up wills at the courthouse seemed vexed that I’d come seeking information and suggested I return later. I explained I was from hundreds of miles away, passing through on my way elsewhere, and I couldn’t return the next day or next week as I again would be hundreds and hundreds of miles away. There would be no camaraderie of sharing a same origin of place, for though I wasn’t born in Chautauqua County I felt a heritage affiliation with this area via all the family who had worked and died there, my paternal great-grandfather had run a feed store on the main street, another relative had run an ice cream shop, an affiliation with all the family who had labored on keeping the roads in traveling order, the Crockett ancestor who had been burned to death in their own burning down home that made big news in the papers for days due the horrifying drama of Samuel vividly witnessed as conscious while burning alive in his bed, and his daughter-in-law badly scorched in her attempt to rescue him. Even with ancestors and relations occupying the town’s cemeteries, there was no “Welcome home!” Kansas was not so inviting, though Sedan greeted one with an artistic mural of a bison in full race over the range and, wanting money spent there, attempted to appear receptive, such as with the yellow brick walk. I had visited Chautauqua County a few times in my youth and I felt no connection then either, my paternal great-grandfather just as disinterested in my presence, not the kind to share a story, he had no desire to converse with or be around great-grandchildren, but my step-great-grandmother, who used to run a little beauty salon on Sedan, was friendlier and showed me their root cellar that was stocked with jars of vegetables and fruits and I worried about accidental food poisoning lurking in those jars and wondered if they’d ever taken refuge in the cellar from a tornado and if it was safe to do so when surrounded by all that glass. We had basements in Richland and in Seattle but it was my time in the Midwest that greatly impressed on me the necessity of a basement or root cellar, so I was astonished that in Augusta, Georgia, basements were rare. The wet clay and high-water table in much of the South resists them. I was told there was no need to worry about it as the South never had tornadoes, but the South has tornadoes, of course. My husband’s family has a picture of the Louisiana home of his maternal great-great-grandparents that was so leveled by a tornado nothing was left except blown apart lumber and children reflecting on the wreckage, gathered for the camera, some in pairs under shared umbrellas, others wore huge straw hats the size of pails, with shoulder wide brims, which oddly don’t look like sombreros while looking exactly like them.

Of course I can’t penalize the town of Sedan for not appreciating I’d history there, certainly for not intuiting that I did, for not caring that, “My family lived here for several generations”, because what’s past is past, I was a stranger, I am not the center of the world, and I can understand a clerk’s annoyance at someone not of the town’s population of 1000 walking up and imagining they might get help without an appointment. That said, what I felt was resisted as the obvious outsider, as is the way of many places, as with the South, which vigorously prides itself on a hospitality that

Eight - 7

can be a veneer of passive-aggressive graciousness if extended at all. An environment where I instead felt surprising humane community was in New York, we were visitors exiting a neighborhood diner where I had insisted we eat our breakfasts as it was everything I wanted of a diner in New York, not a showplace for tourists, I could relax and feel there like it was home territory, and as we were walking down the frigid cold December sidewalk away from the diner my son, then about nine or ten years of age, became suddenly ill (no fault of the diner), and instantaneously from a couple of different sides we had people rush forward with generous assistance, no exclamations, no drama, just immediate, practical help, expecting no thanks. They weren’t shaming, not judging, not asking what we might need, they just had in their hands what would be helpful and gave it to us, their attitudes demanding we not be embarrassed or obligated. They were quick to assist and then vanished.

One will was dug up that I quickly perused as there wasn’t much to it. The clerk found no more, which wasn’t much of a surprise, and I don’t know what I’d hoped to discover in any older wills, had there been such, except that I’ve seen a few from other families, not mine, in which the testator grows loquacious and remarks on their history and spouses and you don’t know for certain your ancestors wouldn’t have done the same until you check out the evidence, but from what I can tell that line of family generally preferred not to leave wills at all. The clerk was so reluctant I felt both harried and imposing-upon with the few minutes I took from her. Futility quickly overcame me, what was I doing there, what did I hope to achieve, the woman was right that I was wasting her time. She pointed me in the direction of the Chautauqua County Historical Society, but they closed promptly at 3:00 p.m., which it already was, and there was no convincing them to stay open for an out-of-towner, my little story of not being able to return didn’t touch their hearts, or they had business elsewhere, and I understand that as well though I was disappointed, so I peered in the window then went away, now anxious for a glimpse of other places where my forebears and relations lived, Pawhuska then Ponca City, and we’d have to rush to briefly set our eyes on them, leaving out all the small towns, before the sun went down. Maybe I would return one day, I told myself, but I never had the opportunity, and Chautauqua County wasn’t exactly beckoning me to return, despite all that familial DNA lying about. A few minutes were taken to wander the empty streets of Sedan and no spirits nudged at me beckoning recognition. Was that the building where my great-grandfather had his feed store? Or was it another store two doors down? I didn’t know. Before moving into town, they’d lived on a place next to the Oklahoma border called Limestone Prairie, where I’ve been told was a large boulder inscribed with that name. This limestone prairie, part of the southern Flint Hills, has evolved a unique tallgrass ecosystem as there is little top soil atop the rock and what there is of it is dry. What I remember of visiting one relative, when I was a teenager, was walking the path to her front door was like wading through a veritable ocean of grass and how disorienting it was not to see above it in parts, I’d never been fully immersed in such an environment before. Much of the tallgrass prairie of the so-called Great American Desert is fertile and good for farming, thus its tallgrass ecosystem was quickly destroyed by settlers. Limestone prairie was instead good for bison and antelope and cattle ranching, not for farming. My family didn’t have cattle ranches and it doesn’t seem they’d have chosen to live there with serious farming in mind as they were

Eight - 8

mostly tradespeople, carpenters, stonemasons. But then I read in old newspapers that while some sections of limestone prairie were only good for tall grasses, others supported wheat farms, and there’s a mention of an ancestor getting in his hay. So what do I know except I do know that hay isn’t wheat.

The United States once had about 142 million acres of tallgrass prairie. Only four percent is now left. When I was a teen, in the early 1970s, my grandmother still had acres of pristine, native, original, genuine tallgrass prairie that had been left her by her parents. I don’t know how many acres my grandmother held but it wasn’t one or ten, it was of a sizable enough portion that the government desired to purchase it for preservation, but my grandparents were looking at other offers. How special was it that my grandparents (A) possessed virgin tallgrass prairie and (B) were in the position of playing a part in its preservation?—well, I thought part A was cool and part B was an amazing opportunity they couldn’t possibly turn down. I knew the importance of the preservation of virgin grasslands, and I implored my grandparents to sell to the government. My grandparents cooly stuck to their argument that if the government really wanted to preserve virgin tallgrass prairie that badly then they would increase their offer to match the highest bidder. They didn’t. I don’t know where their tallgrass acreage was located, whether it was in Kansas or Missouri or both, so I can’t go look at it on Google Maps and see what it became that is no longer tallgrass. Maybe it’s concrete, maybe it’s soybeans or alfalfa. And, no, I didn’t benefit from their selling to the highest bidder, I received nothing from either when they died.

Chautauqua County is at the southern border of the state, inclining a little to the western side of what is southeastern Kansas. I read that the family of L. Frank Baum, author of The Wizard of Oz, has erased conjecture for what inspired the yellow brick road with their knowledge it was based on cobblestone roads in Holland, Michigan, where Baum spent summers as a child vacationing with his affluent New York family. Baum’s descriptions of Kansas came not of a familiarity with Kansas but of his time in Aberdeen, Dakota Territory, so I needn’t feel odd about beginning this chapter, which deals with my father’s mother’s side of the family, in Kansas, for though my father’s paternal line was in Kansas, his mother grew up in a Missouri county bordering Kansas, but they were at least Kansas connected, and part of her family had lived in Kansas on their way to eventually settling in Missouri after the Civil War. Relations of my grandmother were still living in Chautauqua County when I stopped by the courthouse, I hadn’t notified them I’d be driving through as we would only be there briefly and didn’t know when we’d arrive, so my plan had been to just drop by the establishment where they worked, the Emmett Kelly Historical Museum (he was born there) and say “Surprise! Hi!” but when I went to the door I found they were closed on Mondays and it was of course a Monday.

Wikipedia’s entry on the Yellow Brick Road doesn’t mention Sedan but notes there’s a Yellow Brick Road in Wamego, Kansas, in the northeastern part of the state, in Pottawatomie County, where there is a Wizard of Oz museum. And that a part of Route 54 in Kansas has been officially designated as the Yellow Brick Road. Looking it up I find in the 2009 Kansas Code, Chapter 68, Roads and Bridges, Article 10, Naming and Marking of Highways and Bridges, Designation of part of U.S. 54 as the Yellow Brick Road; designation of the city of Liberal as the Land of Oz and the Home of

Eight - 9

Dorothy of the Wizard of Oz. (a) The portion of United States highway 54 from the west city limits of the city of Greensburg then in a southwesterly direction to the Kansas-Oklahoma border, is hereby designated as “The Yellow Brick Road.” The secretary of transportation shall place signs along the highway right-of-way at proper intervals to indicate that the highway is “The Yellow Brick Road,” except that any additional signs shall not be placed until the secretary has received sufficient moneys from gifts and donations to reimburse the secretary for the cost of placing such signs. The secretary of transportation may accept and administer gifts and donations to aid in obtaining suitable highway signs bearing the proper approved inscription. (b) The city of Liberal is hereby designated as “The Land of Oz” and “The Home of Dorothy of the Wizard of Oz.” This sounds very possessive and maybe a little distressing for Sedan with how their Yellow Brick Road appears to be coldly snubbed, perhaps for no other reason than it was a sidewalk. Greensburg, Kansas, is in Kiowa County, in the middle to west part of the state, while Liberal, Kansas, is down in the southwest portion of the state neighboring Oklahoma, in Seward County. In Liberal, Kansas, is a museum that’s stated to have been made to look like Dorothy’s home, and it has its own Yellow Brick Road. The house doesn’t look like Dorothy’s house in the movie but I suppose that’s all right because the house is a real Kansas house that was built in 1907 and Dorothy’s house as described in the book is a little shack and looks nothing like the houses in the movie. There is also a Land of Oz park in Beech Mountain, North Carolina, because Jack Pentes, the designer who was tasked with coming up with an idea for a summer tourist attraction, believed Beech Mountain looked like Oz.

Kansas is a place but Oz is a fairy tale that transforms the Depression Era dust bowl into everyone’s back yard in which, promises the movie, so beautifully filmed, the quest for one’s heart’s lost desire will be fulfilled, “Because if it isn’t there, I never really lost it to begin with,” Dorothy philosophizes. Which sounds the kind of sentimental bell that will pour tears from eyes with the truth that all you need is right where you are, but on second glance makes no sense.

Medium close-up on Dorothy from the front as she sits on her bed clasping her dog, Toto, to her breast. Aunt Em is also seated on the bed, the rear of her left shoulder and gray-haired head in the frame screen right between Dorothy and the camera but not obstructing our view of Judy Garland who will one day die of an accidental drug overdose. “There’s no place like home,” Dorothy says, ecstatic, tearing up, eyes bright, as the film ends and quick fade out immediately as Em rises from the bed. The ending is odd in its abruptness, in the way the film closes as Aunt Em rises from the bed. I’ve rewound it and considered their decision to cut it right there, at that exact moment, not a split second sooner or later. A moment interrupted, unresolved.

As a child, I loved the wise but not overbearing Scarecrow as much as anyone, and as an adult I don’t know whether or not to be surprised that the scarecrow’s origin was in nightmares Baum had as a child in which the scarecrow was chasing him, and that Dorothy was named after a beloved niece of his wife who had died as an infant of five months. Baum would likely say that in the interest of forming a modernized fairy tale he had excised the heartaches and nightmares of his inspirations, retaining instead the wonder and joy. Both wise clown and fool, with his being vulnerably stuffed with

Eight - 10

straw, the primary caretaker and friend of Dorothy, working on emotional memories of the most cherished of one’s childhood toy friends the scarecrow was fashioned to be the favorite of most everyone, just as he was the one Dorothy would miss the most, but he was also insistent on their releasing one another after their time together that was most significantly Dorothy’s journey. I was terrified by Almira Gulch on her bike, in the film, transforming into the Wicked Witch of the East outside Dorothy Gale’s (her very name heralds strong winds) window in the tornado. I was even more terrified by, after the red ruby slippers were translated to Dorothy’s feet from the dead feet of the Wicked Witch of the East, the red-and-white striped stockinged toes of that witch curling up like a fiddlehead fern and withdrawing under Dorothy’s house that had fallen on her—bump—when it landed in Oz. And even more terrorized when Dorothy is in the castle of the Wicked Witch of the West and views in the large crystal ball Aunt Em’s anguished face replaced with that of the Witch who mocks Dorothy calling out for Em in distress. This scene makes perhaps worth noting that though telephone usage had then been expanding, it would be some years before that revolutionary tool of communication was broadly realized in rural America. The movie shows utility poles lining with punctual regularity the dirt road outside Dorothy’s home, the interior of which is comfortably outfitted, but it’s closer to absolutely certain than doubtful that the Gales wouldn’t have had a telephone with a party line on which nosy neighbors could listen in on conversations.

As with many children in the 1950s through 1960s, through most of my childhood I never saw Dorothy’s Kansas transform from a sepia-toned dustbowl to a veritable explosion of color when she opened her door on Oz. Instead, The Wizard of Oz was a black-and-white world on our television screens, and still it worked magic. The film was first broadcast on television in 1956, before I was born, then was broadcast yearly, with the exception of 1963, from 1959 through 1991. The 1959 broadcast was Sunday, the thirteenth of December, from 6:00 p.m. to 8:00 p.m., followed by Ed Sullivan. The 1960 broadcast was on Sunday, December eleventh. The 1961 broadcast was on Sunday December tenth. The 1962 showing was on December ninth. 1964 to 1966 it was broadcast in January, moved to February in 1967, to April in 1968 and for at least a few years was in March and April, I’ve not checked the schedule beyond that. So it was shifted from late autumn, almost a pre-Christmas scheduling, to an early New Year’s spot then to late winter as everyone looked forward to Easter spring. I was checking when The Wizard of Oz came to the television screen because the first dream I recollect was from the summer of 1959 and after a certain point in my life I came to believe it must have been influenced by The Wizard of Oz. I didn’t realize I was dreaming, but having been put down for a nap when my father’s parents and his father’s sister Allena were visiting us in Washington State, my first time to see them beyond infancy, I was startled awake by the frightening laugh of the Wicked Witch, as in The Wizard of Oz. I was convinced what I’d heard was a witch then realized it must have been a strange waking dream, that I’d probably heard my grandmother or grand-aunt Allena laughing in the back yard outside my high bedroom window and it had been translated into the witch’s laugh in the dream. But it wasn’t the laugh from The Wizard of Oz as I wouldn’t have the opportunity to hear it until December thirteenth. It seems that the laugh I’d heard and half-dreamed would have been similar to it. I do know at the age of two I didn’t associate it with The Wizard of Oz, that came later, I

Eight - 10

just was frightened by the witch outside the window. The fact I later associated it with The Wizard of Oz shows the memory being altered after the fact.

After living in the Midwest when I was ten and then having moved to Georgia, I explored the school library in an effort to deepen my connection to Kansas and to try to expand on it and comprehend it better, the purpose for which I turned to The Wizard of Oz, I thought the book might elaborate more, and was excited when I found it was a series, as this meant that much more opportunity to read about Kansas. What I hadn’t expected was that the period of time devoted to Kansas is given more impact and time in the film than in the book. The first four pages of The Wizard of Oz describe the harsh, gray territory of Dorothy’s existence, the four walls of the cabin and its meager furnishings, how her Aunt Em and Uncle have been so brutalized by prairie life that they never laugh and the only companion Dorothy has to brighten her day is her dog. Then the tornado whisks her away to Oz, and I no longer care about Dorothy and her adventures because, whereas in the film what happened in Oz felt emotionally real, in the book I no longer feel anything authentic.

As a child, I didn’t like Frank Baum’s books.

Frank Baum’s remoteness from the midwestern prairie life of Kansas begins with his having been born in New York into a family of considerable wealth built upon barrel-making, oil drilling in Pennsylvania and real estate. He is sent to military school, which he deplores, and when he’s an adult his father attempts to set him up in various businesses such as fancy poultry, but Frank’s not very good at business and instead wants to be in theater, which is fine and good, I’m certainly not going to be critical over anyone wanting to tell stories and go into theater, I used to write for the theater. But Frank’s father dies and the family business essentially collapses. Frank has responsibilities and must earn a living. He takes off for boomtown South Dakota to which relatives have moved and opens a store, but the store fails and he turns to newspapering. His mother-in-law is a much respected feminist who perhaps sometimes ghostwrites for him on the paper. His mother-in-law, who he admired, is concerned with indigenous affairs, in 1878 wrote about treaty rights, in 1893 about the rights of women in Iroquois society, and was reportedly admitted into the Iroquois Council of Matrons. But in 1890, Frank appears to call for the destruction of Native Americans when in an opinion piece he calls them “whining curs”. Frank Baum’s opinion was, “The whites, by law of conquest, by justice of civilization, are masters of the American continent, and the best safety of the frontier settlements will be secured by the total annihilation of the few remaining Indians. Why not annihilation? Their glory has fled, their spirit broken, their manhood effaced, better that they die than live as the miserable wretches that they are.” That’s brutal. Frank’s way of dealing with whites not honoring the treaties they’ve made is to erase those with whom they’ve broken their promises. Nine days later, on December 29, 1890, at Wounded Knee Creek between 250 and 300 Sioux—elders, women and children—were massacred. To this horror, Baum responded, “The Pioneer has before declared that our safety depends upon the total extermination of the Indians. Having wronged them for centuries we had better, in order to protect our civilization, follow it up by one more wrong and wipe these untamed and untamable creatures from the face of the

Eight - 11

earth. In this lies future safety for our settlers and the soldiers who are under incompetent commands. Otherwise, we may expect future years to be as full of trouble with these redskins as those have been in the past.” Baum does lay considerable and cynical blame on the American government and whites in their mistreatment of indigenous peoples, but he still places the indigenous on the side of “other”, and determines the best of what he believes is an unsalvageable situation is their erasure, whereas Dorothy and Aunt Em and Uncle Henry, no matter how gray their sorry lives on the unforgiving plains, are a part of settler occupation to be preserved at all costs, despite the fact that the three eventually, in the book series, elect to abandon Kansas altogether for the better fantasy of Oz.

If I appear to place considerable emphasis on Baum, this has only to do with my three Dorothys, and Kansas, and because The Wizard of Oz proved to be so influential on some artists, and dug so deeply into American pop culture.

In order to refresh my memory, and compare my childhood and adult comprehensions, I tried rereading some of the Oz books, but was unable to do it, they were too frustrating and left me not wanting to waste my time on trying to find in them the purely agrarian heartland “American” fairy tale voice that some tout as part of their intrinsic beauty. I got further with the books when I was ten years of age and was even then dismayed by what I interpreted as colonialist Beyond-the-Atlantic inheritance. The fundamental impetus of Baum’s Oz books ends in seeming an effort to build a white settler fairy tale to lay over the plains landscape obliterating all pre-existing indigenous lore and legends.

In order to refresh my memory I also read, in its entirety, the Laura Ingalls Wilder book in which the Ingalls move into Osage territory, which left me with questions about pa and ma. A reason that people might love this book they’d read as children is that it’s pretty reassuring, despite Laura’s occasional fears, because, as Ma says, everything that works out fine is fine. As children the readers might not hear how Ma is denying very reasonable anxieties on the parts of the Ingalls children, instead what the readers, as children, perhaps absorb is a sense of adventure, most everything appears to them to turn out fine, they might not comprehend how stressed is the Ingalls family and how in peril the children often feel. Also reassuring are the detailed descriptions of how the Ingalls set up camp, then the building of the cabin and barn, the stress is on Pa being competent in all that he does, and for me as an adult it’s interesting, considering the first steps my ancestors who settled about thirty miles away would have taken. But I keep thinking about what’s really going on, what Laura doesn’t know about as a child, which the parents keep saying isn’t for the children to consider, which Laura Ingalls Wilder wasn’t game to confront in her books as an adult.

Laura Ingalls Wilder, whose books I also never bought into as a child, at least lived in Kansas (briefly), the family progressing there by way of New York and Wisconsin. Often, in early published histories of the states and their counties, note was made from place to place of who was the first white person in the territory (I take it for granted usually erroneously recorded), the first white settler, who was the first white woman, whose was the first white marriage and who was the first white child born there. This is why Frank Baum’s books about Kansas life are instead about Oz, a

Eight - 12

fantasy to which Dorothy escapes from a world deadly to white settlers who were killing themselves and their children trying to learn how to live in a place hostile to European practices and sensibilities. No white person was initially “of” Kansas or South Dakota or Iowa, the continent was flooded with people who were not “of”, who having escaped the colonized east coast were on the move until they obtained the Pacific. Then they became possessive and territorial and determined themselves “of”. If their descendants bristle at losing the status of “of” when reminded they are “of” settlers, it’s because the vast majority of the whites who flooded the continent were simply bodies directed out there to occupy and establish colonialist American interests with the aim of displacing American Indians. Wealthy people were amongst them, who had the wherewithals to snatch up mineral rights and other prime resources, but the majority were existentially lost and seeking a home here then there then perhaps over there. They were, yes, Onward Christian Soldiers, for those who thought of themselves as God-ordained rescuers of the new Jerusalems from heathen hands (and not all felt this way), but what they were principally, or became, was the must of the American self-made individual, self-reliant, independent, supposed proof that anyone could start with “nothing” and, by the clever opportunistic virtues of capitalism, make fortunes. The late nineteenth century power housing of this mythology was in the name of one Horatio Alger, son of a Unitarian minister, descended from Puritan aristocracy but by his generation not aristocratic enough to join in the posh clubs at Harvard where he matriculated. Following in his father’s footsteps, he too became a Unitarian minister, with a special interest in moral entertainments for boys, but then he turned out to be a pedophile and was forced out of the church and out of town. Elsewhere, Alger continued his “rehabilitation” efforts centered on boys and birthed Ragged Dick novels about wastrel youth who through hard work and self-sacrifice, gaining the attention of helpful elders, were rewarded with upward mobility, stories written for boys (Alger couldn’t break into a successful living in writing for adults). Laura Ingalls Wilder, too, developed her books for children, as with Frank Baum. One could hazard, influential myths of the American West that informed the tastes of later generations were centered on the indiscriminate receptivity of youthful ears.

But it’s more complex than this because the “not of” white settlers had children and they did become “of” because they were born there, and when you are born somewhere you grow up “of” there. They were no longer English or Scottish or Irish or German or Spanish or French. They were descending of people from across the Atlantic Ocean but they were now disconnected from the place from which they descended, and as the colonies began to intermix after several generations then those of Dutch descent began to marry with English and Irish and who they were initially of was increasingly no longer so simple. They were still not “of” America in the manner of the indigenous American Indian, but they were of the place where they were born, an American landscape, albeit one to which their forbears had imported and imposed upon lifestyles from where they’d hatched. The threat that transpired and remains is of their not really belonging to anything but an abstract concept of “America” as they are descended of imports, but they can’t go back to the old homeland, regardless of whether or not their ancestors left their old homeland because it wasn’t hospitable to them for one reason or another, and while they are “of” they no longer belong, and

Eight - 13

the threat that they might not really belong on the American continent, where they are, creates an existential instability. It’s not masochistic or self-punishing to examine this, instead the anxieties of prior settler generations demand examination, their hopes of becoming “of”, their descendants becoming “of the USA” by reason of their birth here, what they felt they were owed, what they felt they owned, how they looked for places where they might fit, and the needling fears that would arise of how they were, most significantly, psychically vulnerable to being exposed as thieves, despite their rationalizations that to the victors go the spoils, that they were god blessed with the Better Homes and Gardens Seal of Approval.

2

I used to try to comprehend my paternal grandmother through her father’s side of the family, the Noyes, and now I think perhaps a proper understanding can be had only through also acknowledging the family of her mother, the influence of which I’d previously ignored. Perhaps I’d ignored it because my father’s mother ignored it. The Noyes were prosperous farmers, the Brewers were not. Other than the fact she was attractive, I don’t know how my grandmother’s mother caught the eye of my grandmother’s father or vice versa. I don’t know how my paternal grandmother met my grandfather either. My grandmother had ample opportunity to tell me how she came to know and decide to marry my grandfather, and my grandfather had ample opportunity to tell me his side of the story, but neither ever did, and I never got the feeling it was a big romance anyway. It occurs to me to look up whether there was a wedding announcement and I find the 1915 announcement of my paternal grandmother’s eldest sister reads, “This wedding was a surprise to the relatives and friends.” A wedding dinner was given the day following by the bride’s maternal grandmother. My grandmother’s second eldest sister’s 1915 wedding announcement reads, “This wedding was a surprise to the many friends of the contracting parties. It was also a surprise to the bride’s parents. [The groom’s] father knew that their marriage was contemplated but did not know when it was to be.” They had a supper afterward at the house of the eldest sister who had married several months earlier. My grandmother’s only brother was married in 1926 and again it was a surprise to nearly all. “The young pair let it be known to the bride’s mother that the wedding was close at hand but gave no indication of the exact date.” The announcement for the 1928 marriage of my paternal grandparents which, as with the others, takes place away from the old home town, in this case not too distant from where they had been attending school in Kansas at what is now Emporia State University, makes no mention of the family of either except that my grandmother’s youngest sister was an attendant as was a man who that youngest sister would marry the following year in Indiana, a marriage that I don’t find announced in the papers. My grandmother’s father’s family wasn’t religious so it’s not surprising that none of the marriages took place in a church, but one might wonder why my paternal grandmother’s parents weren’t included in any of the marriages of their children, not even informed they would take place. What I know about my paternal grandmother’s father is that he had a glass eye (fireworks accident), he was diminutive in build, and though photos from

Eight - 14

his youth give him the appearance of having light hair his WWI draft registration states he had black hair and brown eyes. I was told the fireworks accident was in his youth but on 7 July 1905 the Liberal Enterprise reports the “lamentable” accident occurred when he was teaching his children how to use fireworks. He had lit the fuse and had thought it had gone out as the outside wrapper on it stopped burning, but it hadn’t, and when it exploded part of the clay packing struck his eye. He was thirty-one, it was three years before my grandmother was born, but her oldest sibling and sister would have been ten. My grandmother’s three elder siblings would have witnessed the accident. My grandmother and father believed fireworks were best left to professionals. A healthy fear of fireworks was passed along to me, that accidents happen, and I’ve passed on that avoidance to my son. Anyone I’ve ever known who likes fireworks has looked upon my fear of them with condescending scorn. “Oh, they’re safe.” I once caught a ride home, in a car in which everyone was smoking pot and cigarettes, from North Carolina to Georgia, and no one told me that under my seat was a stash of fireworks. When I found out, I was, “What the hell!” and they were, “It’s perfectly safe!”

My grandmother’s father was “severe” enough in laying down the law in his family that because he didn’t believe in women wearing pants my grandmother didn’t wear pants until in her sixties, decades after his death, but he also spent lavishly on her clothes so that she prided herself as being, she said, the best dressed girl in the county. It didn’t occur to me until years down the road that the only thing my father’s mother ever said about her mother was that she was always impeccably groomed and that she blued her hair, like it was high art to do so. That this might be considered to be the most remarkable information on her suggests something, though I’m not sure what, even more so as this was how her daughter elected to describe her. And the significance of the bluing of her hair escaped me as when I was growing up it seemed all older women with graying hair “blued” it, which is a method to remove a yellow cast that can occur with gray hair. As far as I was then aware, nearly all older women visited the hairdresser once a week for their hair to be washed and set and their color corrected as needed. I didn’t know this kind of bluing wasn’t popularized or available until the 1930s, which is the decade when my grandmother’s mother was in her 50s, so she was utilizing what was then a new cosmetic treatment, though the dying of hair in shades of blue, green, and purple had briefly entered the high fashion world early in the century immediately before and during WWI. As with men visiting barber shops for a trim, some men for their daily shave, the ritual of the weekly visit to the hairdresser was a significant part of the culture, these visits being also an important part of their social world. They were, many of them, women who didn’t work outside the home and had their appointment scheduled for the same day and time weekly, just as with the other women they might see at the beauty shop that wasn’t a chain but run by a local individual. Rather than the blue rinse my grandmother had her hair dyed a muted auburn, similar to my grand-aunt Allena. My paternal grandfather’s stepmother (his mother died when he was twenty-four), rather than being among the women who only frequented the salon as a consumer, advertised in the 1930s as being then proprietor of a beauty shop that provided shampoos, finger waves, manicures and facials two doors down from the National Bank in Sedan. This wasn’t a minor part of their culture, it was an important part of the observable fabric of their lives in

Eight - 15

which they were trusting another to not only groom them, to ensure they might present themselves at their best, but also required that they submit to grooming in a semi-public environment in which they were viewed in a vulnerable state without their optimal public masks. It means a kind of social compartmentalization in which they were mutually forgiven that hour, more or less, of vulnerability for the maintenance and enhancement of their public face, the self projected on the town’s stage. “Does she or doesn’t she? Only her hairdresser knows for sure,” was a popular mid-twentieth century ad campaign that assured the public wouldn’t be able to tell if one’s hair color was natural or by choice, but a trip to the beauty shop, unless one had perfect privacy, typically meant one being exposed for at least the communal hair dryer line-up, and many had only open beauty stations so every step of the process was exposed.

My paternal grandmother’s mother took a step up on the economic ladder when she married. This meant a certain privilege in keeping up appearances. This great-grandmother was predominately Dutch. If I could speak with my Dutch line of ancestors, I’d say something like:

ME: OK, so you were slime for stealing New York from the Lenape for the price of a few beads and some trade goods—they thought you were leasing hunting rights and you muscled the deal into a real estate bonanza.

THEM: ....

ME: Never mind that. You were in New York for two centuries. Two centuries! And then you get it in your heads to up and leave for Kentucky, where you must have gotten a bum deal, so you promptly picked up and went to where? Kansas and then immediately Missouri. The Ozarks. And there you stopped. Where several generations later you'd sit and chuckle over Petticoat Junction and claim it as your cultural heritage.

THEM: Let’s back this up. Your accusations about New York are flat out wrong. We were little people and didn’t make that land deal. And we weren’t in the Ozarks. Get your facts right.

ME: You were almost in the Ozarks.

THEM: You know, they made an episode of The Beverly Hillbillies at Silver Dollar City.

ME: I’m aware. I was told that many times.

THEM: Petticoat Junction was good. It was based on a real hotel in Eldon, Missouri. But Green Acres, well, Eddie Albert got a bit full of himself with his left-wing views. Got it into his head he had important opinions when he was just an actor. He was no Ronald Reagan.

ME: You were Vanderbilts.

Eight - 16

THEM: Not since 1699.

ME: How did the Vanderbilts become the wealthiest family in the United States, while you made for the Ozarks and poverty.

THEM: We weren’t in the Ozarks.

ME: If you had stayed in New York then maybe your descendants would have grown up enjoying the Museum of Modern Art instead of Sam Butcher’s Precious Moments Chapel in Carthage, Missouri.

THEM: There’s nothing wrong with Sam Butcher’s art. Sam Butcher is a fine artist. He made a good living ministering for God through it, too.

ME: Sam Butcher is neither a fine arts artist nor a fine artist. He’s sentimental kitsch. Art can appear to be kitsch but if it’s exploring and commenting on kitsch it’s not kitsch, it’s struggling for self-awareness, to examine the nature of kitsch, what buttons it’s pushing, how it manipulates the viewer. Butcher doesn’t care about self-awareness, he cares about hitting all those right buttons that bring up an automatic hard-wired response to all the feels that are supposed to be generated by sentimentality. Like the phrase “mom and apple pie” is a button that’s intended to associate the good mom cares for me with good smelling tasting pie it’s my responsibility to give my life in exchange for that sacrificing myself for mom, apple pie, god, and country.

THEM: What are you talking about?

ME: You wouldn’t say that in a real conversation. In a real conversation you’d shut down the conversation with the reply, “I know what I like and that’s all I need to know.” You left Manhattan and MOMA for Silver Dollar City. This makes me bitter.

THEM: We left New York for New Jersey first.

ME: Point taken.

This internal dialogue is tongue-in-cheek. I make an uneducated joke about New Jersey, I’m obnoxious and rude but these are the feelings that happen when your interests and dreams are scorned by people who think, for example, Sam Butcher is the best, they are determined you should think Sam Butcher is the best, they want you to become just like them, they don’t want to consider your views. One gets defensive. Still, I went to YouTube to reacquaint myself with Petticoat Junction, and I took a look at Eldon, Missouri, twelve miles north of the Lake of the Ozarks, and I browsed newspapers. The Shady Rest Hotel of Petticoat Junction was inspired by the Burris Hotel, located near the Rock Island railroad tracks in what was then a three hotel town, and was a plain, two-story, rectangular, unadorned box of a building with unassuming porches spanning both floors in front, no architectural flounce, a standard build for hotels like this from the mid-late 1800s into the early 1900s, in

Eight - 17

exploring places different branches of my family were at I’ve seen many old illustrations of such hotels. It was originally called the Rock Island Hotel, opened in 1889, which means it had been part of the Rock Island Hotel chain kept by the Rock Island Railroad. In the series, the hotel is instead an isolated, sprawling Second Empire Victorian with a Mansard roof, such as was the Bates residence in Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, built on a railroad line about twenty-five miles from Hooterville that has the small general store where Kate, the hotel’s widowed matron, does all her shopping for supplies. The show opens with the three beautiful daughters of Kate who, upon hearing the train whistle, pop up out of a big water tower where they supposedly take recreational baths, it’s a head-and-shoulders shot that does more than give the impression they are nude, so one can associate “hooter” with either the hoot of the train or something other, wink wink nudge nudge. The plots of the episodes I viewed online from the first season are homespun Americana wisdom up against the corporate greed of big city folk, the down home people being for the most part gentle oddball caricatures mixed up with a very few smart ones, like Kate, who look after trying to keep their down home way of life viable. The branch of railroad the Shady Rest sits on is long forgotten and exists solely to connect the struggling Shady Rest to Hooterville, much like a personal taxi. The hotel’s matron lures traveling salesmen to her hotel with the promise of great home cooking and the attractions of her three lovely and curvaceous daughters. If you live in a small town that’s been murdered by the Interstate having bypassed you, much like small towns that had been earlier killed off by railroads choosing to not honor them with a depot, then you’re going to feel a connection with the Shady Rest trying to convince the big city people to not close their little twig of a RR branch. Or if your family was one of those who left behind the farm and small town and settled in the city then the show may feel like it’s providing a glimpse of the small town America in which your grandparents dwelt.

The Burris family took over the Rock Island Hotel in 1910, soon purchasing it, and also operated a livery stable, which suggests they had some measure of wealth. One of the Burris daughters, who had married in 1909 and lived in St. Louis, had a daughter, Ruth, who moved to Kansas City and went into radio, then she married Paul Henning, who had grown up in Independence, Missouri, and also worked for the radio station KMBZ. In 1938 they relocated to the West Coast where they wrote for movies and television. He created The Beverly Hillbillies, said on Wikipedia to be based on “his experiences while camping in the Ozarks near Branson, Missouri”, and while he and his wife eventually purchased over a thousand acres of land there, newspaper accounts and an in-depth interview with him instead name the location of the Boy Scout camp he frequented as being in southwestern Missouri in Noel and that it was by way of camping excursions there he’d become aware of people in remote places who resisted modernization. He described the setting as like Tobacco Road, referring to the stage play he’d once seen in Kansas City, which was based on the book, a combination of social realism and dark comedy about sharecroppers outside of Augusta, Georgia, who are trapped in a vicious cycle of poverty. The play retained enough of the book that it was banned in some cities as immoral. Henning recalled, “and what I wanted to do was escape the week to week depressive setting of the back woods…you wouldn’t want to see it very often because it was depressing, the seeing, the surroundings.” He had previously played around with the idea of what would it be

Eight - 18

like if a person from the time of the Civil War found themselves translated to the present, zipping down the road in an automobile. (And someone probably asked, “But won’t we have to deal with slavery having been abolished? Do we want to go there? Do we want the essential comedic element to be their getting used to no one owning slaves?”) These ideas morphed and combined to become Henning’s hillbillies who he initially conceived as being transplanted to New York as the Manhattan Hillbillies then decided instead on Beverly Hills as it would be too expensive to occasionally film in New York. The Shady Rest first appeared in The Beverly Hillbillies in 1962 then spun off to become its own show in 1963, a Henning daughter starring in the show as one of the three daughters of Kate. In 1965, Henning was executive producer and casting director of Green Acres, which also took place in Hooterville, but with wealthy New Yorkers giving up their sophisticated lifestyle to become rural farmers. I didn’t pay much attention to any of these rural comedies until I was in Missouri in 1967, seated on the carpet in my paternal grandparents’ living room, watching television with them, they were in charge of viewing fare, and with some surprise I realized where I was, southwestern Missouri, was almost the vicinity of the down-home territory of these comedies. I didn’t watch them earlier, in Washington, as I didn’t care for them, they were too corny, and I had assumed the Beverly Hillbillies hailed from Texas because as far as I was aware that’s the state that was known for black gold oil, and I’d believed Green Acres happened in rural New York.

Ruth Henning grew up in St. Louis, Missouri, but as a child she spent summers at the Burris Hotel. Petticoat Junction was intended to nostalgically extol what were imagined to be old time, small town values, based not on an isolated hotel twenty-five miles from the nearest small town of Hooterville, which had a population of about forty, but a hotel in a small town that grew from a population of 2000 to over 3000 between 1910 and 1930. Admittedly, it’s funnier to have the hotel in the middle of nowhere, built where the train dropped the lumber, but it might be argued that the root story has little to nothing to do with Ozark hillbillies. As for the Burris hotel, Paul remarked that the grandchildren were warned to stay away from the traveling salesmen.

Henning’s view on the Ozarks, at least the more remote pockets, was of an oppressive place into which he didn’t want to immerse the television-viewing public, from which he was giving his hillbillies the opportunity to escape into cathode ray tubes all across America, Wednesday nights on the Columbia Broadcasting System, the number one show in the Nielson Ratings for its first two seasons. Paul Henning had also written a couple of episodes for The Real McCoys, introduced in 1957 by the American Broadcasting System, done with by 1962, the first of the rural comedies, and its premise was similar. Looking up their first episode, I find it opened with a car much like the Clampett’s a-kilter Ozarkmobile, only it’s piloted by the McCoys, an Appalachian family from West Virginia who have come to California because they’ve inherited a ranch from a relative, the difference was the Clampetts had a more extreme transplanting from insulated Ozark hillbilly culture into fantastic wealth.

John Ford’s 1941 movie adaptation of Erskin Caldwell’s 1932 novel, Tobacco Road,

Eight - 19

opens with scenes of a ruined plantation mansion followed by Jeeter Lester’s old jalopy rambling down the road supposedly outside Augusta, Georgia, but Augusta’s terrain has changed so it would be unrecognizable to Caldwell’s Tobacco Road resident, we are in Appalachia or the Ozarks, Augusta transformed to have rolling hills that are instead California mountains, and one may say, “Of course, it’s a movie,” but a choice was made as to what type of landscape in which to place the family of Jeeter Lester. Actually, the movie opens with the notice, seemingly inscribed in earth, that the stage play opened 4 December 1933 in New York “and has played continuously since then, breaking all records for length of run in the history of the American theater”. The play shut down in May of 1941 after a run of 3182 performances, three months after the release of the movie, and has briefly returned to Broadway several times. In the list of longest-running broadway shows, its position is now twentieth place, the first eighteen all being musicals with the exception of one musical revue, nineteenth place belonging to the play Life With Father that ran 1939 to 1947 and was a comical and sentimental tale of family life in the New York upper crust during the Victorian years. That Tobacco Road was popular as a play is mind-boggling, also that the novel has sold over ten million copies, because Caldwell’s depiction of the Lesters is the damning bleakest of representations of an American family, their utter ruination associated with the Great Depression and the absentee landowner of the land on which they sharecrop. having abandoned their own farm, but the boundaries and expectations that compose the rudiments of a humane and civilized life are so alien as to have been lost for generations. As with Jeeter’s car, nothing functions any longer. The only boundary left to break is the oppression of poverty. Because Jeeter refuses to move to Augusta to work in a mill, insistent that God has made man to till the land, he and his family spend every moment of their lives starving to death on a diet of corn meal and fat back rind. He lives with his wife, Ada, a daughter with a cleft lip, Ellie May, and a sixteen-year-old half-wit son, Dude, the rest of their children who hadn’t died revealed to have fled for the city, with no love lost as they will have nothing to do with the family they left behind. Jeeter and Ada married off Pearl, their twelve-year-old blond-curled and blue-eyed daughter, for about seven dollars, and we learn that if she looks mysteriously different from the rest of the family it’s because she’s not Jeeter’s, but Jeeter has fathered numerous children outside his marriage, and is acknowledged as so perverse that he’s told by Bessie, a preacher woman friend, the reason God gave Ellie May a cleft lip was to protect her from Jeeter’s lust and he agrees this has likely prevented him from having sex with his own daughter, an aversion that wanes as the novel progresses. The first chapters are concerned with Lov, the husband of Pearl, on his way home from fetching turnips, he has stopped to complain to Jeeter about how Pearl hasn’t slept with him yet, she won’t even speak with him, no matter how he treats her, whether he gives her small gifts or beats her, and he hopes her father will help him with this matter, he even considers having Jeeter help tie Pearl up so he can rape her. While Lov complains, Ellie May scoots her sex-starved rump across the sandy ground toward him until she is seated on his legs. The rest watch in hypnotized anticipation that the two may have sex right then and there, but are preoccupied as well with the prospect of stealing Lov’s turnips. Which they do, they attack him while he’s distracted by Ellie May and rather than sharing the turnips Jeeter runs off to hide and eat them by himself. A widow, Bessie, also hungry

Eight - 20

for sex, afflicted with a birth defect that has deprived her of a full-fledged nose, decides that God has ordained she and Dude should marry so she may turn him into a preacher man, like her deceased husband. She convinces Dude to marry her in exchange for the privilege of driving a new car she purchases with insurance money from her husband’s death, and though Dude is underage Jeeter gives his consent as he hopes to also use the car. After the marriage, Bessie moves in with the family and while she and Dude retire to consummate the marriage the rest of the family attempts to look in through the window, and Jeeter thereafter becomes preoccupied with having sex with Bessie as well. Dude treats the brand new car so carelessly it immediately begins to fall apart, plus it was low on oil before they even left the show room. He runs into a wagon, killing its black driver, and if one is disconcerted by everyone’s lack of concern for the man’s death, and determines this must be racism, by the book’s end one has an opportunity to reconsider their callousness when Jeeter’s mother, who has been starved by the family, is not once but twice run over by Dude, then left by all to lie where she was crushed into the earth. When they check her after a couple of hours they find she managed to roll over and crawl a couple of feet toward the house before breathing her last. What they have positive to say about her is that at least she never complained. Pearl runs off to Augusta after Lov attempts to tie her up and rape her. In consolation, he’s given Ellie May to take home with him. The novel ends with Jeeter setting fire to the broom sedge to burn it off, as his father and grandfather did, even though burning the broom sedge never killed the boll weevils, even though he will be planting no crop, but the wind turns during the night and he and Ada are burned up in their shack.

The story is told in a repetitive style, as if it had been serialized and the reader must be reminded at the beginning of each chapter of what is happening. Caldwell makes the reader aware of how these illiterate and insensible individuals have been taken advantage of by every capitalistic cog and wheel of a predatory society, but their treatment of one another is no more sympathetic, and that he takes up three chapters with Ellie May dragging her rump across the sandy soil to sit on Lov’s legs, while the rest of the family watches transfixed, leaves the reader to question where Caldwell’s use of dark comedy becomes instead exploitative pulp fiction titillation at the expense of his desperate characters. Though it can be argued what the initial three chapters accomplishes is to wholly immerse the reader in a life that has no moral compass, Caldwell’s dark comedy is so relentlessly bleak, it seems a crippling onslaught of lethargic misery that leeches from the novel to consume a horrified audience, so by the book’s end the reader feels as emptied of initiative to do anything as Jeeter’s family, one can scarce imagine being able to move to help the dying grandmother, one is even amazed Jeeter has the energy to bury her (we’re not even confident she’s actually breathed her last), one wonders how anyone could muster the scant iota of energy left in their starved souls and bodies to do anything but lie down and wait for exhaustion to complete the job of transforming their flesh into dust. It may be we find it difficult to imagine the conjuring of energy because anyone with a moral compass has been excised from the book’s pages, they’ve already fled Tobacco Road. As for Jeeter, who accepts the rationalization that his daughter was given the cleft lip so that his disgust of it would prevent him from raping her, it’s near impossible to feel any

Eight - 21

sympathy for his desire to one day till the soil again, he and Ada burning up in the shack while they sleep would seem a cleansing blessing for all concerned, if the reader wasn’t left a scorched witness.

On the way to becoming a movie, the play injects some humanity and energy by having Ada become concerned for Pearl, who is only a subject of conversation in the book but appears in the play, running home away from Lov. When Jeeter takes her captive for Lov, Ada takes up for her daughter, attempts to save her, and is the one run over by the car. Pearl sobs over Ada as she dies, then flees for Augusta, Ellie May takes off to live with Lov, and Jeeter reprimands Ada’s body for dying for nothing other than helping Pearl. Pearl doesn’t physically make it into Ford’s film, in which Ellie May loses her cleft lip, becomes a beautiful “older” woman of twenty-three, and joins Lov when Pearl runs off. In the play, the “Captain” has died, who owned the land on which Jeeter is a tenant farmer, and with the Great Depression the Captain’s son has fallen into his own financial problems so that the land is possessed by the bank and will be converted into a research farm. In the movie, the bank gives Jeeter the option of renting his land, and as Jeeter can’t pay for it, the Captain’s son pays his rent for six months and stakes him the money to plant a crop. So Jeeter and Ada are left with a measure of golden hope, but the audience doesn’t know if Jeeter will mend his slothful ways and muster the energy to separate himself from his porch to work.

It’s barely a hop, skip and gulley jump from the movie to The Beverly Hillbillies, in which Ellie May is fused with golden-haired Pearl, and amuses television audiences with how she is ever disappointed when she must release the men she comically, innocently takes captive as potential husbands. Dude becomes the good-natured simpleton Jethro, and Ada and the grandmother are blended to become Granny, both further transformed so they may be genially compared to the comic Li’l Abner, which entered publication in 1934. A little of the movie’s passive, daydreaming Jeeter survives in Jed, who as the wise family patriarch mediates the family’s introduction to the wealth and conveniences of Beverly Hills.

The Tobacco Road Lesters wouldn’t have counted themselves as kin of Appalachian mountain folk, or the Beverly Hillbillies, separated from Missouri by near half a continent. Georgians despised Erskine Caldwell for Tobacco Road but when the play toured, despite efforts to ban it, Georgians filled the theaters in which it was performed, and a 22 November 1938 review in Atlanta reported there was much appreciative laughter and applause though the audience was disappointed by some of the punch having been taken out of the play by the actors stepping around lines that might be found objectionable, that the characters could not be accurately portrayed without the expected profanity, and that the original script was less objectionable than the current form that called attention to the deletions. Dr. M. Ashby Jones, a Baptist minister, said he had no desire to see the play but that he was fundamentally opposed to censorship. A 1987 article revealed that Caldwell’s books weren’t on display in the town of Wrens, Georgia, where he’d spent part of his youth, they were kept by the librarian in a box in a small room behind her desk so they were available to “teachers and students” who asked for them.

Eight - 22