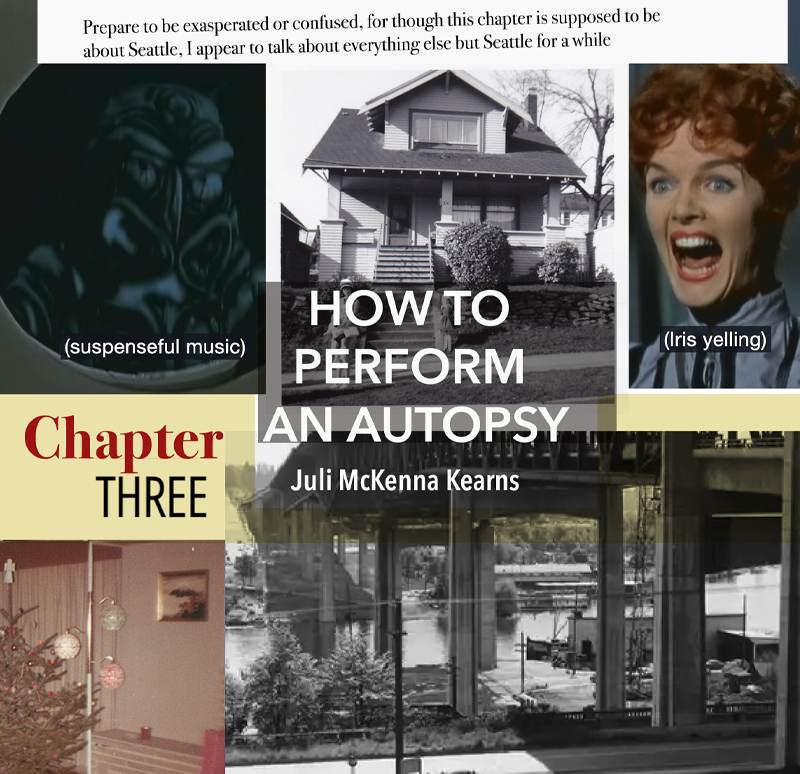

THREE

Prepare to be exasperated or confused, for though this chapter is supposed to be about Seattle, I appear to talk about everything else but Seattle for a while

1

Humans are unable to walk in a straight line. Let them loose, with nothing to guide, and they unwittingly walk in circles.

I supposed I was going to write now about Seattle (steep hills, water water everywhere, bridges, a volcano peering down on us all, there are many photos online of the different stages of old Seattle building itself, astonishing images of early Seattle regrading, cutting the tops off its hills in order to create an accessible city and still there were steep hills) and instead find myself in Augusta, Georgia, about thirteen years of age. Taking a break from auditions for the Augusta Choral Society, I stand in a hall to a side exit/entrance of the parish hall of the Episcopalian Church of the Good Shepherd where are some old photos hanging on the wall that I take an interest in and examine for their history of the church that was in 1869 first built and admitted to the Diocese as a parish, then was built better and bigger in 1879, torched itself in 1896, and was rebuilt within the still-standing salvage of its brick walls in 1898. The history of the church is unknown to me at the time, the photos divulged little, everything I now know I’ve looked up, which means digging around for news articles as the church’s current website only gives a few brief sentences. The fire, which occurred on November twenty-second, as reported in Savannah, Georgia’s The Morning News, was caused by a stove in the belfry, which the church used for spillover warmth when it was considered not sufficiently cold for the church furnace. The fire, originating in the stove pipe, burned through the neighboring rope to the bells so they couldn’t be used to sound an alarm. Located in the Sand Hills—also called Summerville—area of Augusta, the church might have benefited from the Summerville community having recently purchased a chemical engine for putting out fires, but courtesy of the burning of the Church of the Good Shepherd it was found they didn’t have the necessary chemicals for their new machine to do its job. While the slow-moving fire burned, the church furniture, pews, chancel rail, altar, pulpits, organ, hymn books, carpet, even its memorial stained glass windows were rescued, though the window back of the chancel fell to the ground and broke as it descended the ladder. If we can picture and hear anything in the organized tumult to save what could be saved, it’s the people on and around the ladder, navigating the salvage of that undoubtedly very heavy and unwieldy window, their expressions and exclamations of ire and disappointment as it escaped their grasp and crashed to the ground, shattering.

One wonders at the arguments that were either begun by or resolved by the realization the new chemical fire engine didn’t have the required chemicals to work.

Who first sensed the fire? Did a child tug on the sleeve of a parent and say she smelled smoke and was shushed? At what point during the service did they realize the destruction of their Sunday peace? If the building held memory of the fire, it never reached me.

In the autumn of 1909, in Chautauqua County, Kansas, my great-great-great-grandfather Crockett, on my father’s side of the family, was burned alive at the age of seventy-seven when the gas stove in his bedroom exploded. This will sound like

Three - 2

ancient history, but I clearly recall when I was ten years of age and told by my paternal grandfather how he was the last child born in the two-story Crockett farmhouse, he having been born there the year that it burned, and as my great-great-grandfather Crockett lived into the mid-1930s, and his wife into the mid-1940s, dying at eight-nine, my McK grandfather would have heard the story directly from them, as well as his Crockett mother and McK father, and Crockett uncles and aunts and grand-aunts who lived nearby. The fire made bold headline news in the local paper with an account of how Sarah, my great-great-grandmother, J. K. Crockett’s daughter-in-law, attempted to rescue the already bed-bound, elderly man from the burning room, but at the door he wrestled out of her arms and fled through the fire back into the bed where he rolled himself up in his bedclothes and writhed as the fire that wholly destroyed the two-story farmhouse consumed him, his “frenzied” family able to see it all. Sarah was hailed as heroic, overcome with smoke, her face, body and limbs painfully burned in her attempt to save her father-in-law. The fire had begun while her husband was at the barn tending stock. The deceased being from Columbia, Missouri, where he still had family, near two weeks after the event a letter to the Columbia Daily Tribune related it would be a while before Sarah would recover from the shock and her injuries. As the house was home to three generations one can fathom the difficulties with the loss of all their household goods and items of sentimental value. The Sedan Lance either had a taste for the disturbing hard facts or didn’t flinch from disclosing them, as it’s closing paragraph on the tragedy, stated, “Only the trunk of Mr. Crockett’s body was recovered. The head and limbs were practically all burned away.”

Onlookers believed J. K. Crockett was still conscious while burning because he was writhing, when instead it is likely he died quickly, perhaps even overcome by smoke inhalation. The writhing would have been an effect of heat shrinking the muscles, causing postmortem flexing and the pugilistic pose observed in burn victims. To ensure my facts are straight on this I’ve scanned a few websites, including the National Library of Medicine on the National Institute of Health website and was unexpectedly treated to several photos of remains that would have been something like those recovered of J. K. Crockett, I guess the NIH imagines if you're looking for information on "pugilistic attitude" and burn victims you don't need a "Warning, disturbing photos below". And I've seen, of course, the images of monks and others self-immolating, the first one being the 1966 protest of the Mahayana Buddhist monk, Thich Quang Duc, I saw that when I was nine, the whole world saw it, which was disturbing enough in the 1960s that Ingmar Bergman included footage of the event in his film, Persona, about an actress who quits talking and the at-home nurse with bad boundaries who becomes abusive with her. While she is in the hospital the actress sees the footage of the man burning and is overwhelmed by it, this event that happened thousands of miles away to someone who has nothing to do with her, yet it is traumatizing. I've seen other images of burn victims as well, but the ones on the NIH page were still surprising in their over-contrasted depictions, their starkness, perhaps surprising because I was seeing them while thinking about J. K. Crockett. And as I was thinking about J. K. Crockett they did make vivid what was left in the Crockett house, and I wondered whose duty it was to collect the remains, was it the county coroner's, and who was the county coroner in 1909. William George Jack, a husband of

Three - 3

J. K. Crockett's niece, Ermie, had been county coroner for four years, I was able to find he probably last served in 1906, and William Naughton was the coroner in 1909. J. K. Crockett's wife died a little over a year after her husband's death, her obituary stating she hadn’t been well since the fire.

When I was seven, in our small rented house on Everest in Richland, my bed was the black-and-white tweed sofa, demoted from living room privilege and stuffed in a sundries room off the kitchen with baskets of laundry waiting to be ironed. I blearily went from it one night, through the kitchen, into the living room, an immediate right turn into the short hall to the bedrooms of my brothers and parents, and to my parents’ bed to drowsily rouse them and tell them I smelled something burning in my room. “You’re imagining things, go back to bed,” my father said and I took him at his word and returned to the sofa bed and that’s the last I remember before waking in the back yard where was also the sofa bed that the fire department had carried down the rear stoop into the yard. I listened with vested interest as a firemen stressed I was lucky I wasn’t dead. The sofa bed had been situated so its back was pressed against an electric radiant wall heater, the foam in the back of the sofa had smoldered-melted and the fireman told my parents it had been near the point of exploding into flames, which was why I was lucky to be alive, because combustion would have instantly consumed it. When I had returned to bed, I had apparently been overcome by the gases or smoke, I don’t know, my parents had woken back up to the smell of something burning, had gone to the catch-all room and found me in a situation beyond their control, had removed me and called the fire department. I can still smell the thick acrid fumes given off by the burning foam. The ghost of them irritated my sinuses, throat and lungs for seeming days. Fire department calls were typically reported in Pasco’s Tri-City Herald. 6 September of 1961, a Tuesday, they responded to a 9:35 morning call to our home on Blue Street for “lint in clothes dryer, no damage”. On 29 January 1967, a Thursday, at 2:46 in the afternoon the fire department responded to a call at our 1803 Mahan Avenue home for a grease fire in the oven, no damage. No report for a sofa fire at 2024 Everest Avenue made it into the news though there was damage. The black-and-white tweed sofa that had been with my parents since they were first married, which they’d replaced in the living room with a new, sleek, dark brown upholstered Danish modern, was destroyed, the back of it burned away. After the firemen determined I was probably all right and didn’t have to go the hospital but said that my lungs would be irritated and if I had trouble breathing the next day I should see the doctor (I felt I wasn’t completely all right and should go to the hospital as I was having trouble breathing but I kept quiet as I reasoned if they couldn’t tell this I must be okay enough), having heard the description of how I was lucky because the sofa had been at the point of exploding, after the firemen left I asked my parents, just to confirm it from their lips, if I could have died, if my life had been endangered, because I wanted them to admit I had been right after all when I went to them and said I smelled something burning. They said I was never in danger, so my brain played tug of war with what I’d heard the firemen say and what my father and mother said. I asked if I’d passed out from the smoke and they said no I had just been sound asleep, and for a long time I thought well maybe that was true, I shouldn’t exaggerate and think I’d been overcome by the smoke or gasses, even though I also knew I had woken up being attended to by emergency personnel, and that I’d not simply been asleep, I had been unconscious.

Three - 4

Because we all for some reason afterward acted like this had never happened, I used to sometimes forget the fate of that sofa and wonder, “Where did that sofa go? It was such a classic piece.” I never forgot about the fire, the firemen, how the sofa being pressed up against the electric radiant heater was what caused the fire, and yet I would oddly forget about what happened to that sofa specifically. As a young adult, again forgetting, I once asked my father whatever happened to the black-and-white tweed sofa and he said he didn’t know. I would try to imagine if it had made it to the basement at Mahan, I would wonder why in the world they would have dumped it because it was such a great sofa, and then I’d recall, oh, that’s right, and I see it again sitting that night in our back yard with the giant hole in its back revealing the blackened and melted interior, and there are the firemen, and my parents tell me I was carried outside the house because I was sound asleep.

The sofa bed instilled in me a deep respect for and fear of fire. When my son was young and we lived in Midtown a serial arsonist who targeted apartment buildings somehow entered the front section of our building despite everyone being on high alert. He set fire to the stairs but the blaze was quickly discovered. He was caught not long after, having set twelve fires, and was a taxi driver who had once been a police officer and had already been in prison. Perhaps someone had propped open the front door of the building, and that’s how he’d gained entrance, which can be problem in apartment buildings with people coming and going who don’t take seriously how a secured entrance is a safety precaution for everyone in the building. I later found the building had also been through a bad fire in 1974 in which fifteen people had to be rescued. An old, vacated, wooden house across the street from our current apartment building was struck twice by an arsonist several years ago, not long after we moved in. The house, only partly destroyed, was not torn down, only boarded up. For several years afterward, when the humidity was just right, the scorched smell of the timber would be revived and drift into our apartment.

OK, I’m looking at information on polyurethane use in upholstery, its role in fires, how it behaves, about the production of cyanide fumes, trying to determine if the sofa had polyurethane, recognizing it as apparently polyurethane, it fits in the window for when began use of polyurethane in upholstery, and now I’ve restored my fire anxiety with enough fuel for a lifetime. Enough, don’t think about it.

Because we never talked about the fire, and I only knew the heater had been “radiant”, when I was older I became confused with this having been a radiant steam heater, which it wasn’t. Looking at photos, I realize and recollect we had vented heat in the other rooms, but the catch-all room had originally been a garage that had been made over into two rooms before we moved in, and for heat had radiant electric installed against the wall. For years, without thinking about it, I’d simply thought “radiant heat”, I knew from listening to the firemen that the radiant heat had been a danger and the sofa shouldn’t have been pushed up against it, radiant heat, keep everything clear from a radiant heat source, and so as an adult when living with radiant steam heat I made sure to keep nothing close to steam heaters, just as with electric space heaters. When I saw others had pushed up things next to their radiant steam heaters or were putting things like textiles on them during the winter, I told them why I worried about

Three - 5

their safety, I'd tell them about me and the sofa bed. I was greatly concerned due my own misapprehension, and while I was perhaps over-cautious, I still read it’s not recommended that objects be placed on or near radiant steam heaters as any extreme heat source can be a danger with a flammable material or can dry out “fairly inflammable” items and make them more susceptible to catching fire from other sources. Straightening out my own story, looking at photos, I find how I was wrong all these years about the heat source but what the fireman said is confirmed. Reading up on polyurethane foam in upholstery I realize the acute danger in which I’d been, that it smolders then combusts, and that it also releases hydrogen cyanide fumes and carbon monoxide, gases that are responsible for overcoming people and causing smoke inhalation deaths. Far more people currently die from being poisoned by these gases than by fire. They are overcome and never have a chance to escape.

Parents are humans are fallible beings are beings who make mistakes who make innocent and guiltless mistakes, they are people whose abilities are conditionally influenced by the environment in which the family exists. Parenting is difficult and is daily burdened with personal and circumstantial regrets. My parents perhaps felt guilty, so we didn’t discuss the fire, and my father said he didn’t know what had happened to the sofa. Or their reluctance may have had more to do with a self-centered fear of exposure of negligence or irresponsibility. There’s a difference. Because the couple of times I did ask about the fire, my mother would ask why I tried to make them out to be bad parents. All that said, I survived, I was rescued. All that said, my parents preferred I not remember.

With the Civil War, southern Episcopalians had also decided to secede. Separating from the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States for political not doctrinal reasons, they formed the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Confederate States of America, its first convention held at St. Paul’s in Augusta in 1862. The Charleston Daily Courier, on 22 October 1861, reports on the naming of the breakaway church at a convention in Columbia, South Carolina. Judge Phelan, of Alabama, argued that a name ought to be descriptive, that “Protestant expressed nothing” and should be removed, but he wasn’t in favor of instead instituting “Reformed Catholic” because “Reform could not in any just sense be predicated of Catholicity. It was an essential note of the Church, and it would be as well to talk of reformed sun or moon…” Bishop Elliott of Georgia, who had led the movement to form the breakaway church, a lawyer and alumni of Harvard and South Carolina College, argued the retention of Protestant as important because Protestantism memorialized protesting the decrees of the Council of Trent and the supremacy of the pope etcetera. A Rev. Mr. Pinckney was willing to concede “the evils associated with the term Protestant” but he felt the term Catholic was “equivalent to Romanism and just as full of evil as Protestantism.” Others wondered why anyone was arguing about this at all, they weren’t there to make radical changes such as changing the church’s name (as if breaking away from the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States wasn’t radical). Bishop Atkinson of North Carolina, also educated in the law, alumni of Yale and Hampden-Sydney College, held the word Protestant expressed a spirit, and he couldn’t condone it as a protesting spirit was one of unrest, doubt, denial and unbelief (again, as if breaking away from the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States because you wanted

Three - 6

to keep your slaves wasn’t a form of protest). A first vote for “The Episcopal Church in the Confederate States of America” failed. A second vote for “The Protestant Episcopal Church in the Confederate States of America” passed. One doesn’t know whether to think “of course” or be a little bewildered by the fact that, as the Civil War commenced, southern Episcopalian clergy and laymen and lawyers found the energy and concern to argue over whether their new church should be identified as Protestant or not. After the war, that church was dissolved at its second convention, and its errant Episcopals reunited with the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States.

Established in 1736, Augusta, Georgia, in 1861, was the second largest city in Georgia, while Richland, Washington, didn’t exist, and Seattle, a camp in 1851, not incorporated until 1869, barely existed. Seattle had no newspaper until 1863, no telegraph until 1864, in 1870 its population was about 1100, and though it was 3000 by 1880 that fell short of the city of Walla Walla, in the southeast of the state, which now has a population of about 34,000 while Seattle’s is about 750,000, and few outside the Pacific Northwest have likely heard the name Walla Walla.

Hard to believe now, but when we moved down to Augusta in 1967, most people I met had never heard of Seattle, so they certainly hadn’t heard of Richland despite its role in the Manhattan Project. The Seattle World’s Fair of 1962 was supposed to have placed the word “Seattle” on everyone’s lips, and still people in Augusta often didn’t know anything about Seattle, much less Richland, despite Elvis Presley’s appearance in the 1963 film It Happened at the World’s Fair, which was filmed in Seattle. I was elated when the television series, Here Come the Brides, debuted in 1968, because at least the idea of Seattle was home entertainment once a week, I got to hear its name, and I religiously watched the show though it didn’t mend the ache of having been removed from Washington State. The so-called Mercer Maids were the inspiration for the series, brought from New England to Seattle in 1864 because women were scarce, about nine men for every female. That Asa Mercer, first president of the Territorial University of Washington (1861-1863), went to Lowell, Massachusetts, hoping to find females who might be game for relocating to Seattle makes sense when one considers that the textile mills of Lowell had been for several decades a destination for young New England women from poor families who would send money back home, also women who were orphaned or partly orphaned. The experience of independence and bad working conditions resulted in the women becoming activists, staging strikes in an attempt to improve their situation, organizing petitions and the Lowell Female Labor Reform Association. In 1864, production at the mills was down because of the scarcity of southern cotton due the war, so Asa Mercer made his case for female immigrants at the Unitarian Church in Lowell, with the promise of a teaching job in the Pacific Northwest. Eleven women were recruited, several of whom were daughters of a mill superintendent who had been put out of work because of diminished mill production, and he would emigrate to Washington State as well. The second recruitment effort, in 1866, instead targeted women made widows by the war and daughters made orphans, teaching jobs again promised, but the main attraction was the high potential of marriage. Whereas hundreds were said to be expected, only about forty-six women were recruited, including ten widows with and without

Three - 7

children, the poor response blamed partly on newspapers fomenting distrust in Asa’s effort despite the fact he had been appointed Immigration Commissioner for Washington Territory in 1863. The grandmother of my father’s mother had been a mill girl at Pacific Mills in Lawrence, Essex, Massachusetts, not far from Lowell, but she was known to have been there in 1854, the first year Pacific Mills was in operation. Which I mention because I’ve already read up on these mills because of the family connection and so I immediately understood why this would have been considered a potential area for recruitment in cooperation with Unitarians. Had she been at the mill ten years later might she have taken the long ride on that ship to Seattle, hailed as a utopia?

As with Richland, Seattle was not a place in my childhood that was psychically fenced off after we’d left, because I was now a product of Seattle and it influenced my expectations and how I felt about other places, comparing them to it.

When one is a youth in Augusta, Georgia, and is from Washington State, one is going to feel disjointed by how different are their histories. That’s probably true for any two places located in different regions, but Augusta and Seattle were different worlds. Seattle was active and cosmopolitan, a seaport city over which hung in the sky the vision of white-capped Mount Rainier, 29,000 feet high, never mind it is still an active volcano I didn’t know that at the time and never perceived it as a threat. How it related to Seattle, presiding over it, was not unlike the silk art of Mount Fuji, a tall pagoda in the foreground, which hung over my childhood on our living room walls in Seattle, Richland, and then Augusta. When I was ten years of age, while I didn’t imagine everyone had mountains to look up to, it didn’t occur to me that our move to Georgia would change this and would mean no more mountain views. In the silk screen, in the foreground right is the slim architecture of four of five stories of the Chureito Pagoda, depicted in red and black, surrounded by the black silhouettes of cherry trees, and in the background center against the light pink wash of either a sunset or sunrise is the white cap of Fuji, the bottom of the 12,390 foot mountain hidden in cloud. I have only just now learned that it is the Chureito Pagoda depicted in the art. For years I’ve wondered what pagoda this might have been and have finally located it. This painting is a faithful depiction.

And I’m confused as the pagoda was built in 1963, but by the time I thought to question the origin of the painting, which is when we were living in Augusta, my mother said that a red-haired boyfriend who had been courting her before she met my father, one who was quite smitten with her, who was wealthy and determined to marry her, had several of these paintings that he was selling or something something, and he had given one to her as a pre-engagement gift, but then she’d met my father and had decided to marry him instead. This was a story repeated to me as an adult. The problem is that, as I have stated, the pagoda was built in 1963 as a peace memorial, and my parents were married in 1956. The first time this painting appears in a photo is on our living room wall in Seattle, Christmas of 1963. The view in the painting is one like the perspective often seen in professional photos of the Chureito Pagoda with Mt. Fuji beyond, so similar in orientation of the pagoda to Mt. Fuji, though artistically represented with some artistic license, that there’s no denying this is the same pagoda, and the finial of the pagoda in the painting is the same as on the Chureito Pagoda.

Three - 8

On eBay I find old silk embroideries and paintings for sale that show a very similar pagoda with the mountain in the background, but these typically are remote views of a pagoda next to a lake and a red bridge, sometimes a shrine or a house also shown. One piece for sale gives a circa date of 1930, which briefly throws me, and it shouldn’t, their “circa” is simply wrong. After a comparison with tourist sites, I’m inclined to believe these paintings are each a fictional conglomerate of at least two shrine sites near Mount Fuji and reoriented to give the impression of their resting on a nearby lake.

The Chureito Pagoda is part of the Arakura Sengen Shrine, and overlooks Fujiyoshida City. One website shows a photo of the Chureito Pagoda, while relating instead the history of the Fujiyoshida Sengen Shrine, also given as Kitaguchi Hong Fuji Sengen Ninja, that is on the north side of Lake Kawaguchi and was constructed after the ninth-century eruption to appease gods associated with the mountain. Another is the Kawaguchi Asahi Shrine, but the Chureito Pagoda is instead at the Arakura Sengen Shrine between the Kawaguchi Asama Shrine and the Kitaguchi Hongu Fuji Sengen Shrine and separated from each by about a thirty-minute drive. The vintage mid-1900s art I’m seeing online creates a romanticized landscape by giving the viewer everything all at once, Fuji, shrine, pagoda, cherry blossom trees, lake, sometimes one or two small Japanese sailboats, sometimes a red bridge and sometimes a natural brown wood one, sometimes a couple of women in graceful kimonos crossing said bridge. These are not faithful representations of a scene but an imaginary landscape and all are anonymous. These are images that unify in one landscape many of Japan’s touristy highlights but it is not a faithful representation. Most people are familiar with “The Great Wave of Kanagawa”, a woodblock print by the artist Hokusai. “The Great Wave of Kanagawa” is from Hokusai’s Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, published 1830-1832, and not to be found in any of those prints is a single pagoda or red bridge. The Chureito Pagoda landmark isn’t shown because it didn’t yet exist. It wasn’t part of old Japan.

In Richland, the painting became highly symbolic for me of the town’s link with Japan through Hanford’s production of the plutonium that went into the Fat Man weapon that was so horrifyingly dropped on Nagasaki, which is an association that isn’t unmoored by the discovery my mother’s origin story of the painting was fake. But—what the hell, why the fake story?

Down the same line, yet not, my husband’s grand-uncle, Harry, gave him an acoustic Harmony guitar when he was a child and told him he had played that guitar riding the railroad with the famed Woody Guthrie “This machine kills fascism” folk singer, my husband only to discover when he was about thirty and had the guitar repaired that it wasn’t made until the 1950s. He now looks on the story as having at least attached him to a cheap and unplayable instrument he might not have otherwise held onto, which when repaired turned out to be a great guitar that he loves, and he had only kept it all those years because of its historic and romantic link to Woody Guthrie. My husband grew up with this story and guitar, he told the story to me, and I knew nothing about his grand-uncle’s history and had no reason to doubt it, just as my husband had no reason to doubt it. Is it possible Harry might have ridden the rails and jammed with Guthrie? I don’t know. He lived most of his census life in Mobile, Alabama, a boilermaker in railroad shops and shipyards, also up in the District of

Three - 9

Columbia where a brother of his was also a boilermaker then opened a restaurant concession in the Treasury Building. Harry was footloose, marrying twice and fathering a couple of children, each marriage to last only a couple of years with his ex-wives immediately remarrying, so he had the freedom to roam. He had a sibling living in California in the 1930s whose husband was a railroad man. Harry’s youngest son had lived in Florida, he was a switcher on the railroad, and he died at twenty-three, several days after an accident in which his leg was crushed during the coupling of two cars, requiring amputation—a story I’m only telling because of the sad but novel peculiarity that his leg was buried by his mother in the short time before he died, when it was thought he’d survive, so he is interred in two different cemeteries in different cities, his leg in Tallahassee, where he did die, but the rest of his body in the Pensacola cemetery, where other maternal relations were buried. On the Tallahassee tombstone the remains are described as Bobbie’s leg, his epitaph revealing he was, like his dad, a musician, “God wanted a song bird in Heaven, so He took our Bobbie away.” I learned about Harry's son being buried in two places when I was trying to assess the possibility that Harry may have met Guthrie, thinking of probabilities of Harry's journeying based on what kinds of jobs he held and his lifestyle. With other stories I’ve since heard about him I can imagine his having once been a traveling man. Guthrie, born in 1912, road the rails from the mid-1930s to about 1940. All it would take was jamming with Guthrie once for Harry to be able to take pride in saying he’d played with him. We can’t not prove Harry didn’t meet and play with Guthrie, and we can’t prove that he did, just not on that guitar. Which is how things are, life doesn’t supply us evidence for every story passed along to us, not even most of them, because life doesn’t work that way. Sometimes people wildly fictionalize themselves, sometimes their lives are fictionalized by others. Harry would have had other guitars before the 1950s Harmony, musicians remember their instruments like they’re a part of their bodies, Harry wasn’t confused, he would have known when he’d acquired that particular Harmony, and he may have decided his story wouldn’t have been as good if he’d said, “I played a guitar like this with Guthrie.”

The painting of the pagoda. My mother’s fabrication is so nonsensical it’s impossible for me to process. Why attach the story of a man to whom she was pre-engaged about 1956 to a painting she didn’t acquire until 1963? Why make it a gift from this guy with the fiery red convertible when she instead would have acquired it in Seattle? Admittedly, I always thought the origin story behind the painting was a bit odd and had a vagueness to it that made it fuzzy, but it never occurred to me she was lying about it, just that maybe some of the particulars were dusty. It never occurred to me that this wasn’t a painting that she’d had when she married my father.

Except there’s that story of a fire that supposedly destroyed her belongings just before she married my father, and while working on the Lawrence chapter I came to wonder how much of the story was true. It seems if that story was true, this painting would have been destroyed as well, and it wasn’t. But of course the painting wasn’t destroyed because it didn’t exist until 1963, and the story of the fire in Lawrence may still be untrue or greatly exaggerated if a fire did happen.

Three - 10

I keep expecting to look up the Chureito Pagoda one day and every website that says the pagoda was built in 1963 will be changed to a date before 1956, proving my mother right and me wrong despite everything I’ve read.

Well, wait. After having seen it writ hundreds of times the pagoda was built in 1963, after having spent too much time looking for what month it was completed (my hope was to find a more reliable source) and only seeing “1963”, feeling it was a real close shave there with the pagoda being built in 1963 and the painting appearing on our wall in 1963, though this would not have been impossible, I’m now on the Chureito Pagoda Guide page and it states construction was completed in April 1962. When I search using this date, I find also that construction commenced April 1959, nearly three years after my parents were married. I am further rewarded with a photo of the pagoda under construction in 1960, all steel beams surrounded by wood scaffolding.

2

Back to the Church of the Good Shepherd in Augusta, Georgia, that burned up in 1896 but was kind enough to leave its brick shell in which the church was rebuilt. Logically, I ought to instead focus my lens now on Seattle, but I’m not ready yet. I’m working my way there. While I’m working my way there, I may as well mention that part of my great-great-great-grandfather McK’s family was in Seattle not early early but early enough they were called pioneers, arriving a few years before the great fire of 1889. They were several first cousins of his, Bartos/Bartows, children of his aunt Mary McK, who had settled in Minnesota for a while then moved to Seattle as adults, bringing their widower father, Samuel Bartow, with them. In Seattle, the family went immediately from grading streets to pawnbroking, loaning money, banking, real estate, then lawyering, and it seems they did well for themselves, better than their family who went to Kansas and Oklahoma or Oregon. When the great fire of 1889 burned down their pawn slash loan business, along with twenty-five blocks or 125 acres of the downtown business district and waterfront (one million rats died, loss of human life was low), they set up a tent on the ashes and continued loaning money. These were all professions and businesses alien to the other McKs. Samuel Bartow had married Mary in 1839. Samuel’s (believed) sister, another Mary, would marry Robert Eugene McK, a (believed) brother of my great-great-great-grandfather McK, in 1846. She was thirty, which in 1846 meant she would have already been considered a spinster by some. Her husband was twenty-five. They would have six children and then Robert McK would abandon her after the children were grown and lead a life of serial bigamy. They had no bankers, lawyers, or money lenders in that McK line, and none in my McK line. The Seattle branch did a class reset that took them some steps up in the world away from their McK cousins so that a descendant would become the second mayor of Mercer Island, an affluent community, I don’t know how this move up the social and economic ladder works but in this case it had some co-operation and dedication between the generations, plus, they seem to have landed on their feet running from the moment they hit Seattle and I don’t know how that happens either, but a plan was had to move into a top dog position, at least a stage above a number of the laboring working class. In Hennepin, Minnetonka, Minnesota, the population was 1069 in 1880 and 1441 in 1890, while in Seattle the population was 3553 in 1880 and 42,837 in 1890, an increase of 1112.5 percent. They’d decided Seattle was the place to be, they were part of that massive influx of people, and despite the competition they still managed to climb the ladder.

After the great fire of 6 June 1889, Hall’s Standard Safes, of San Francisco, did the same thing they did after the October 1871 great Chicago fire (about 2100 acres consumed) and took out significant newspaper ad space composed of accolades from Seattle customers on how their safes fared in the fire, and Barto & Godfrey (two of the sons changed their name from Bartow to Barto with the move to Seattle) gave a glowing report, which wasn’t only good ad copy for Hall’s but for them as well. “We had one of your 78 jeweler’s steel lined safes in the great fire of June 6, and when we opened the safe found the contents in perfect order. We gladly recommend your make of safes as affording absolute security for jewelry, papers, books, etc., and for ourselves would use none other.” Before the fire, in 1887, they regularly advertised themselves as a “Loan Office. Notes and real estate bought and sold. Money advanced on horses, cattle, wagons, buggies, pianos, household goods, watches, diamonds, and valuables at low rates. Washington st, rear of Horton’s Bank.” The person who initially

Three - 11

partnered with the Bartos in business was a jeweler, George M. Godfrey, who was from Wapello County, Iowa, his family pioneers there in the 1840s, like Bartow and McK relations of Samuel and Mary who had moved to Van Buren County, Iowa, by the 1840s, neighboring Wapello. By 1895 George Godfrey was big Seattle news as an alcoholic from whom his wife obtained a divorce when a hired detective caught him with a prostitute (not described as such but the address where he was caught is the give-away) but had many friends and was well-liked, yet in January of 1905, nine months before he succeeded in drinking himself to death in October (“final collapse due to long-continued alcoholic excess” said the paper) he was also accused by a miner named Dougherty, who he’d met at a Pike Street saloon, of getting him really drunk, taking him back to his home then not letting him go over a number of days, even employing force, keeping him in a state of intoxication, and extracting money from him by various schemes, a lot of money from him, with the help of Godfrey’s cook, Joseph Duteau, and several unnamed women who were there. The miner, near seventy years of age, had come down to the big city after seventeen years up in Alaska, one of the tens of thousands who headed to Alaska at the time of the Kenai Peninsula gold rush of 1888, or maybe he was late for the Forty-mile district gold rush of 1886, he was already positioned for the famed Klondike Gold Rush of 1896, and what the hell does he know about civilization after that kind of isolation, probably lost a few fingers and toes to frostbite, he may have boasted in the saloon about the digits he’d lost and the several good claims he’s gathered, easy to peg as a naif ripe for a “bunko game”, which was what Godfrey’s cook was arrested for as part of this, following an investigation of several days that promised more arrests to follow but I find nothing else in the news about it. By that time Godfrey appears to have been no longer associated with the Bartos and probably hadn’t been for a while. His then business partner, Lee Melleur, several days before Godfrey’s death, had applied to be appointed his guardian in order to get him help. Godfrey’s one child, a daughter, had made the request that Melleur intervene in order to save her father and the “considerable property” he stood to squander away in his state of dissipation. She would become a popular short story writer whose fiction was placed in many well-known magazines of the day. She never married, living with her mother until her mother’s death. They relocated to Los Angeles, California, which I imagine would have been for her career, and I wonder if she may have gotten uncredited work fixing dialogue in scripts. The reason I hone in on dialogue is I went to the bother to read a story of hers and she had the knack for natural dialogue.

Enough description is in the Daniel Dougherty news item that makes it sound solid true, I’m inclined to believe much of the story was true, but I wonder if he may be the same Daniel Dougherty who in June 1906 was reported as going to a doctor in Lewiston, Idaho, with the request he examine him for insanity, as “people were telling him he was crazy and he would like to know. He has some mining claims out of which he thinks friends are trying to beat him.” He may be the same Daniel Dougherty who is in the Washington State Soldiers Home by 1910, the age fits.

Dougherty had been swindled, it hadn’t been in his mind. Was he experiencing trauma from his experience? In 1905, Duteau had gone to prison for grand larceny for the swindle. He had been released in August, on his own recognizance, had gone to a bar where he’d been in a fight and broken his leg, been returned to jail, then was released to the care of his wife.

Three - 12

Duteau, not long after his release from jail, less than a month before Godfrey died, sued him and his partner for wages he felt he was owed for the extra duties he’d been pressed into as Godfrey’s French cook, which included “going to some saloon nearly every night and bringing back Godfrey, whose clothes he had to take off and care for or throw away, and who had to be bathed and nursed back to consciousness after the nightly sprees to which the plaintiff charges his employer was addicted.” Plus, when he was fired, he was locked out of his room and wanted $264.25 compensation for valuable presents and trinkets left behind. After Godfrey’s death, he painted Melleur’s house (did Melleur feel sorry for him so gave him the job?) but did such shoddy work of it that the house needed to be painted again, which made the news as he tried to put a lien on Melleur’s house as he wasn’t paid for messing up Melleur’s house. In 1907 he was sued for $10,000 for alienating the affections of another man’s wife. In 1908 he showed up at Melleur’s office claiming “to have evidence that reflected on a certain well known woman of Seattle” and Melleur drew a gun on him and ordered him out of the building. A 1903 article shows he had indeed been previously married to a “young wife” who he claimed to the police had eloped with a boarder and he wanted them to find her, then returned to say “never mind” as she was staying nearby with her mother. In 1909, don’t ask me how, but he managed to marry the daughter of a well-known lawyer from Hennepin, Minneapolis, he was forty-five, she was twenty, then in 1915, the year her father died, Duteau started his own business as a real estate broker who also did mortgage loans, which he heavily advertised in the paper. So it’s looking like Duteau had been sketchy, and he might have reformed? Not so. He lands in prison again in December 1915 sentenced to six months for real estate grand larceny.

First Robert Barto had moved to Seattle, the eldest son of Samuel, and he would have been Barto & Godfrey. In 1880, back in Minnetonka, Minnesota, he was still farming, according to the census, then in 1887 in Seattle the census says he was in real estate and then in 1889 he gave himself as a lawyer then in 1900 a money lender. I don’t think he was a lawyer like we know lawyering today. His sister, Margaret, had also moved to Seattle with her husband (a carpenter), there in 1887, but they moved on to Idaho then settled in Spokane. The father, Samuel, moved to Seattle to live with Robert and died there in 1890. Before or after the fire, I don’t know, in the year after 465 buildings were built in brick, not wood, a rather astonishing revitalization. In 1900 brother Luther was a laborer/warden still in Hennepin, Minnesota, then in 1910 he is in Seattle and his profession is “own income”. I’m not sure what he was doing and he died in 1919. Horace Barto, a son of Robert’s, in 1910 is given as the president of Barto & Sons’ bank. Between 1900 and 1910 the bank makes several appearances in the Seattle news. The first is July of 1907 in The Seattle Star. The headline is “To End Business of Loan Sharks”, and the story is about how a suit was filed to “determine the validity of salary as assignments by county employees to usurers. W. H. Borrow was employed during May as an expert in the county assessor’s office. On June 12 he assigned his salary to Barto & Sons’ bank, an institution which makes a practice of loaning money to city and county employees at considerable above the legal rate of interest, taking salary assignments as security. Barto & Sons filed their assignment and demanded a warrant for Borrow’s salary, which Deputy County Auditor Brier refused to issue, unless ordered to do so by the courts. The suit commenced today is by County Auditor James P. Agnew against Bartow & Sons’ bank and Borrow, and will determine the validity of these assignments before the salary warrants are issued. If

Three - 13

successful, it will end the business of loan sharks among county employees.” That raises eyebrows over the Bartos and how they loaned money. A 1910 article in The Seattle Star shows the problem was still ongoing, the headline reading “Will Drive Loan Sharks from Hall”. The situation is described as, “Three thousand, five hundred and forty-two persons drew salary warrants in the comptroller’s office this month, and a majority of that number will be affected by this order, as a majority of the city employees are patrons of practically two loan agencies, that of Barto & Sons bank and of Ronald C. Crawford. These firms advance money to city employees and take out at the rate of 3 per cent a month for interest, although the notes which the city employee signs read at the rate of 1 per cent, the maximum allowed under the state law.” The order was that no more assignments of wages would be accepted. Barto & Sons’ bank still appears to have been around in 1919, then Horace is down in New Mexico in 1920, he owns a farm, and that’s the last I see of Barto & Sons bank except for a lawsuit against them that continues on to 1923. I don’t know. Horace was in Jackson, Oregon, by 1930, working as a photographer, then he died.

Robert had died in 1909 but Barto & Co., which had first appeared in 1891, continued on and was still advertising in 1954, situated then at 505 Third Avenue across from the County City Building, having moved there in 1949. They were advertised as “Loans and Insurance”. Joseph, another son of Robert, had become a lawyer, admitted to the bar in 1915, and in 1918 went into partnership with Alfred H. Lundin, the county prosecutor, their firm said to be the “oldest, original law partnership” in Seattle with offices in the Alaska Building and Smith Tower. Joseph became deputy prosecutor at that time. He served on the board of governors of the Washington State Bar Association from 1937 to 1940, and in 1948 he became president of the Seattle-King County Bar Association. Thomas, another son of Robert, in the Seattle’s Jan 1936 The Veterans Review was given as “operating one of the very few legitimate loan agencies in Seattle”, which was Barto & Co. Joseph’s obituary said he had also helped run Barto Loans, Inc.

It sounds like the family was getting itself in scrapes concerning their loan and banking businesses and needed a bonafide lawyer on their side, so it was fortunate Joseph wanted to become one, and not only did he become a lawyer he became a deputy prosecutor immediately, which one could hazard positioned him to make things easier on the family, I don’t know. It may be that he raised the family business into secure legitimacy.

A last image to go with this story, like the Church of the Good Shepherd fire, the Seattle fire moved slowly enough that people were able to retrieve from offices and homes what was important to them—and think about it, where will they carry them that is assuredly safe—by hired wagon their belongings went to the harbor where they were loaded on ships before the wharves caught on fire and the ships hauled anchor and moved out into Elliot Bay to watch through the night as Seattle burned. As a result of the fire, thousands were displaced and “5000 men” lost their jobs, I don’t know if that figure includes women. A lot of people were going to be needing loans.

Three - 14

3

If the brand spanking new Church of the Good Shepherd in Augusta was built in 1879 that means some white, donor individuals were feeling prosperous and motivated, namely Margaret Gould who had been formerly a member of Augusta’s St. Paul’s. Nothing in the South (or nationally) existed in a racial vacuum, so, with reconstruction having ended in 1877, wondering about the mood of White Augusta, I look to the Augusta paper for a random bit of news that might give an idea of how they were picturing racial relationships for readers, and am surprised to be pointed West, back to Kansas. The top news left column in the Augusta, Georgia, The Evening Sentinel, 26 April 1879, was on the Forty-sixth Congress, the headline reading, “The Negro Must Go!”, Mr. Haskell of Kansas denying hostility, but that they just didn’t “consider it wise to have thousands of poor people cast upon one point destitute and homeless.”

1879 was a key year for the exodus of southern African-Americans to Kansas, promised homesteads and the right to vote, and John St. John, then governor of the state, had personally extended a welcome to southern Blacks. The Exodusters, as they were called, in 1879 numbered between 10,000 to 20,000. Between the censuses of 1870 and 1880, the population of blacks in Kansas increased by 27,000 to number over 43,000. African-American rights in ex-Confederate states having been generally abandoned by Washington, D.C., in 1877, with the end of Reconstruction, Kansas held out the promise of equality. The pros and cons of the migration were broadly and heatedly discussed in the Black community, Booker T. Washington for it while Frederick Douglass, then marshal of the District of Columbia, was among those in opposition, some feeling that the fight for liberty needed to continue in the South. Senator William Windom, of Minnesota, due the exodus, had in February brought to the Senate a petition from The Negro Union Cooperative Aid Association, and the Freedmen of Shreveport, Louisiana, seeking an investigation of the loss of civil rights that spurred the exodus. The petition read, in part, “We are a poor, friendless, dependent, defenseless, landless, ignorant class, in a state of modern feudalism, freed by a generous Government, but left to the will of the former slaveholders, a landed aristocracy, and placed at their feet, bound hand and foot.” In case you’re wondering if Seattle caught any of this exodus, in 1880 there were only 180 African-Americans in the whole state of Washington, 1000 by 1890.

In the family photo box, my father's childhood was represented by a photo of him, four years of age, with his only and elder brother, both attired in spic-and-span playclothes, hair parted on the left, combed to the side and pomaded so not a strand will escape to wave in the breeze. A note reads the image was taken “out at the farm” and the printer’s mark on the back reveals it was developed in Shreveport, Louisiana, where they would have been visiting a sister of my father’s mother who had somehow moved to Shreveport during a divorce from her first husband due unfaithfulness and cruelty, Cora was a clerk for a “big oil” company (never named in hometown Liberal, Missouri, news it’s just given as “big oil”) and then they were transferring her from Shreveport to Tulsa, Oklahoma, and several days later instead of moving to Tulsa she had become the wife of a “prominent planter and merchant” whose uncle had been mayor of Shreveport, and whose grandfather had been a plantation owner shown in the 1850 census as having had sixty-six slaves, including thirty-nine women, twenty-seven men, thirty-one children fifteen and under, in the 1860 census that grandfather

Three - 15

was worth over eight million in today dollars. The wealth and status accrued from the ownership of people before the war was still conferring wealth and status long after the Civil War. From Cora’s first marriage to the cruel philanderer, my father and his brother had a cousin, Lena, in Shreveport, but she’s not pictured in the photo, nor is anyone else, just the two boys. Cora had divorced the cotton plantation guy four years before this photo and thereafter spent several decades working as a secretary in the city electrical inspector’s office. When she retired, a photo was published in the paper of her handing over her job to her daughter. Lena, who had been hailed as a pretty blonde on the society pages during the mid-1930s, would go on to marry a divorced optometrist and had one child with him, a son, whose obituary reveals that after attending Allen Military Academy in Bryan, Texas, he went to Principia College in Illinois (a Christian Science-founded school), Centenary College in Shreveport, LSU-Shreveport, and the University of Graz in Austria. Whatever he was studying that would take him from Louisiana to Austria, something somewhere went wrong because all else that I know of him from the news is that he was “well over six feet tall, about 230 pounds” and would chase down “beer bandits” with a claw hammer when working as a night clerk at a Circle K in Shreveport, which is where he was murdered at the age of fifty, in 1991, shot to death in an apparent attempted robbery, thus having the distinction to be the fourth convenience store clerk killed in Shreveport in fifteen months. No suspects, the murder was never solved. I don’t know if my father knew any of this, but I doubt it as after my grandmother’s death in 1985, and the death of her last sibling the same year, the news from that part of the family likely dried up. The photo of my father and his brother, in Shreveport, would have been a record of the visit, sent to his parents from their aunt Cora. Fifty-four years later, Cora is already dead ten years, her husband long before, and their son is found shot in the neck behind the counter of a Circle K convenience store. Did he piss off the wrong person with his claw hammer? Some customers, the paper reported, wondered if that was the case. Maybe it’s only that he was paid by Circle K to be at the wrong place at the wrong time. There was no sign of a struggle. The police wouldn’t reveal to the press if any money was stolen. Any of the plantation privilege his grandmother had married then divorced, if it had filtered down to him, had run out. Less than a month before the murder, the paper had published a notice that real estate belonging to him would be auctioned off in five days to pay off some of his debts. He was given a Christian Scientist burial.

Had former slaves of the Louisiana ancestors of Cora's second husband made their way to Kansas?

The way America unfolded over the generations, families spread across a big country, losing sight of one another, I could have one day, on a trip, walked into that Circle K and would have had no idea I was paying a second cousin for a cup of bad Circle K coffee. Go back seven generations and many of us would be related, though seven generations doesn’t begin to involve us all enough that I am likely to find “family” in any room I enter. This second cousin, his parents deceased, perhaps inherited from his mother letters and photos that may have shown my father’s family and shared ancestors, things I’ve never seen and which became meaningless when he died so made their way into the trash or a flea market. He had a couple of half-sisters from his father’s first marriage but they weren’t acknowledged in his obituary nor in their

Three - 16

father’s obituary, which suggests a break in the family, and with that break those half-sisters were unlikely to have been interested in whatever had passed down to him from his mother’s side, their father’s second wife, a step-mother they had perhaps not welcomed, I don’t know.

Caddo Parish, the home of Shreveport, was spared in the Civil War, it even prospered, and was particularly violent after the Civil War, for which reason it earned the name “Bloody Caddo”, a stronghold for White Supremacy, known as the lynching capital of Louisiana and the second largest site of lynchings in the South. The neighboring Bossier Parish had also escaped fighting on its land, and had violently suppressed black freedman after the war, twenty-six lynchings of black men occurring there. Bossier Parish had been the first to secede and the last to surrender. The Dickson plantation had been on either side of the Red River in both Bossier and Caddo Parishes.

The South wasn’t happy to see its Black population migrate out as they needed agrarian labor. Southerners who wanted Black labor working their fields, as well as those in the North who opposed the migration, circulated counter propaganda on the misery of the migrants in Kansas. The Mr. Haskell cited above was Dudley Haskell, the Haskells a Lawrence, Kansas, family who had arrived in Kansas in 1854 as itinerant farmers from Massachusetts, members of the Second Party of the New England Emigrant Aid Company who were proponents of Kansas becoming a free state. As Chairman of the House Committee of Indian Affairs, Dudley would successfully lobby for Lawrence to be the site for the industrial training school for Native Americans which would become Haskell Indian Nations University, and is its own bag of worms, as they say, for this happened during a time of aggressive assimilation, denial of Indigenous culture, and the boarding schools to which Native children were removed were harsh in their military regimentation and their efforts to supplant the children’s families and ancestral culture with a forced adoption of White American.

In the 26 April 1879 article, The Evening Sentinel reported, “It is really refreshing to hear philanthropist Windom and his fellow saints repudiated…by the Republicans of Kansas. The men who fostered this scheme and deluded the poor blacks of Mississippi and Louisiana to inhospitable emigration, dire distress and early graves are the worst enemies of the negro…”

But, regarding Dudley Haskell, that’s not what had happened. There had been such a recent, dramatic influx of Black immigrants from the South into Kansas that Wyandotte, Kansas, by virtue of its location at the junction of the Kansas and Missouri Rivers, close to the state line, had received about 1000 immigrants in less than two weeks in March and April, equal to a quarter of the population, and they were having trouble finding housing and food for them. Haskell was worried southerners in Congress would kill any proposed resolution to supply tents and rations, so when the governor telegraphed asking him to contact the secretary of war for permission to use facilities at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, Haskell replied he was willing but that Southern congressmen were “wild over this exodus & they hope & pray (apparently) that enough of the poor creatures will come to want [in Kansas], to deter the rest from leaving.” He felt there was no hope of aid from Congress and that the proposed

Three - 17

legislation, doomed to fail, would diminish private contributions. Relief for Wyandotte came instead by deferring immigrants to Kansas City, then Topeka, Kansas, where temporary barracks were constructed. On April 26th it had been considered that an address should be made that better informed freedmen of conditions in Kansas, but this was then decided against as it was felt the southern press would rework such to their own advantage and wholly repress emigration. Which happened anyway, as we see with the Augusta paper framing Haskell as declaring, “The Negro Must Go!”

Also on the front page of The Evening Sentinel were two columns devoted to the “memorial oration” delivered that afternoon by a Mr. Gary congratulating the South on its commitment to principles rather than policy, upholding the rightness of the Confederate cause. The address, described as “patriotic”, was delivered to the first annual meeting of the Confederate Survivors’ Association. In 1878 there had been the dedication of a seventy-six-foot-high Confederate Monument on Augusta’s Broad Street. To complement the 1879 Memorial Day celebration, The Georgia Weekly Telegraph, out of Macon, Georgia, reported that in Augusta there was a military parade, the Confederate monument was decorated with garlands, and the statues of Robert E. Lee, Stonewall Jackson, Thomas R. Cobb, and William H. T. Walker were crowned with laurel wreaths. And yet Augusta managed to spare paraders for the grand Memorial Day parade that took place the same day in Atlanta. Just imagine all the young lovelies of Augusta, prompted by their busy mothers, seated around tables chatting as they wove the laurel wreaths that would dress the heads of these statues.

1879 seems like a long time ago, but less than a hundred years had passed when I landed in Augusta, and the monument still stood, there was still segregation, and the monument still stands as I write these words. The inscription, in part, reads, “…For the Honor of Georgia. For the Rights of the States. For the Liberties of the South. For the Principles of the Union, as these were handed down to them by the Fathers of Our Common Country. In Memoriam ’No nation rose so white and fair: None fell so pure of crime. Our Confederate Dead.’” Even though I was only ten years of age when we moved to Augusta, I would look at these monuments and understand they were socially oppressive acts, even acts of psychological terrorism against Black individuals, and I wondered why others didn’t see this. But the fact is they did see it, which is a reason the monuments existed.

The wife of the first rector (priest) of the church of the Good Shepherd in Augusta was a Julia McKinne Foster, niece of Margaret Gardner Gould who paid for the $18,000 1879 structure (insured for $8000). Margaret's husband, Artemas Gould, originally from Worcester, Massachusetts, was a wholesale grocer then investor in textile manufacturing in Augusta, then president of the City Bank of Augusta, incorporator of the People’s Savings Bank, director of the Planter’s and Merchant Bank, and had already footed the bill for the land upon which the earlier Victorian Gothic wood and batten building (planks of wood dressed up with, in this case, thin cedar wood strips over the seams of the panels) was constructed in 1869. These were very wealthy Episcopalians who desired to be remembered as dedicated, devoted. We weren’t from the South but as a young member of the church, studying the brass plaque memorials on the “furniture” during Sunday morning mass, I’d taken notice that a Julia McKinne was part of the church’s history. Not knowing anything about

Three - 18

her, not knowing much yet about our McKenneys, I assumed we weren’t related (we aren’t) because my McKenney family had made for the Great Plains, but in my youth it felt a little odd to have my given and family names united in the church’s history. It had the quality of a haunting that was, yes, only accidentally personal, but if a grave is passed that bears a name similar to one’s own and one feels an irrelevant chill, it is still a chill. With their lack of experience, as preteens and teens step over the threshold into a world that, in its chaotic newness, feels mysterious for too many wrong reasons, it’s no wonder the romantic distresses of Victorian Gothic literature would be popular among them. But after a year or so I did convince myself of the absurdity of that sense of haunting.

Apart from the history of its Alphabet Houses, Richland hadn’t much in the nature of architecture to impress, certainly nothing pre-WWII, but Seattle did, and ever since I had been drawn to buildings that might remind me of Seattle, which were uncommon in the Augusta. While this High Victorian Gothic church didn’t recall Seattle for me, its parish hall did, with notes of old public school dark wood wainscoting contrasted by white plaster walls. My mother had begun singing in the Augusta Choral Society after we moved to Augusta, which meant that leading up to Christmas she for months sat on the couch in the living room with the score while on our Magnavox stereo-console she played Handel’s Messiah over and over again, Hallelujah, hallelujah, for the Lord God omnipotent reigneth, Hallelujah, The kingdom of this world is become the kingdom of our Lord and of his Christ, and He shall reign for ever and ever, King of Kings, and Lord of Lords, Hallelujah, hallelujah. For Easter it was Haydn’s The Creation. Others so afflicted will understand how it is that one can come to hate the Messiah, and its “Hallelujah Chorus”, which is breathtaking the first and second time around, if performed by a good choir, then becomes a tiresome, bombastic spectacle for which one must traditionally stand, because nearly a full four decades after its 1743 premiere, it was written that King George II was so awed by the music that its magnificence pulled him to his feet, but when heard enough times the dragging of even youthful bones out of what has likely been a very uncomfortable seat for three hours of Handel feels an imposition only alleviated by the fact this means next is the intermission between Parts II and III, which is not as good as the whole business being done with for another year. Now it’s confessed by historians that King George II likely never stood for the “Hallelujah Chorus” and one wonders how the tradition started and demanded that even audiences in Augusta, Georgia, in the 1960s and 1970s should honor that never-was-action, by also standing, over two centuries distant from King George II and across the Atlantic and on the other side of the Revolutionary War. It didn’t happen out of the blue, someone decided to manufacture a tradition for a reason, one wonders why, which had less to do with the “Hallelujah Chorus” than perhaps a reminder of subjection to royalty, so that over two centuries and an ocean away if one didn’t stand, despite not even knowing who was King George II, then everyone would glance askance like you aren’t being a patriot and standing for the Pledge of Allegiance to the United States of America or the National Anthem. It took me thirty years before I was able to listen again to the Messiah, and only then due a beautiful baroque approximation performance I happened onto on the radio on a drive between Atlanta and Augusta.

Three - 19

When I look to see what information I can find on the choral society, I locate a record of their performance history and if it’s correct then in 1967 they performed the Messiah, Part I and Nos. 26 (“All We Like Sheep Have Gone Astray”), in 1968 they performed The Creation, and the Messiah, Part I and Nos. 33 (“Lift Up Your Heads, Oh Ye Gates”), in 1973 they are listed as performing the Messiah and the “Hallelujah Chorus”, in 1974 they performed Haydn’s The Creation, then in 1974 they performed the Messiah, Part I and Nos. 22 (“Behold the Lamb of God”). So, apparently, we weren’t treated to the whole Messiah ever, and we weren’t treated to the Messiah (originally written for Easter) and The Creation cycle yearly, but I can guarantee that every time the Messiah, Part I was performed, so too was the “Hallelujah Chorus” because the Messiah without the “Hallelujah Chorus” was as incomplete as green eggs without ham. Between 1967 and 1974 the choral society also performed, among other things, Anton Bruckner’s Great Mass in F Minor, Giuseppe Verdi’s Requiem, Zoltán Kodály’s Te Deum, Johannes Brahms’ Requiem, Mozart’s Requiem, and Maurice Duruflé’s Requiem, but I know my mother wasn’t in any of these performances which means it was her choice to stick with Haydn and Handel, and if I remember correctly she became upset with the society and dropped out of the 1974 season, a year before the founder and conductor, Emily Remington, born in South Carolina, graduate of Juilliard, reorganized her life with a move to Charleston, South Carolina, where she then founded the Singers Guild for the Charleston Symphony.

After having heard for years how our mother’s fantasy career as a concert pianist had been unfulfilled, she was finally up on stage, not as a pianist but as an alto in a chorus, she got to dress up in basic concert black and revel in applause. One time, early on, perhaps the earliest time I saw them perform, was at Augusta’s Bell Auditorium, the building a WPA project that opened in 1940, was split into an auditorium and a music hall, and when the main stage was combined sat about 5000 people. To my eye it was a disappointing, shabby place, the interior and exterior displaying a morbid defiance against creative architectural imagination, but a circa 1940 postcard promises it is “one of the largest, most usable and modern auditoriums in the Southeast.” My intuition was the South was against giving nice things to the public because the lower classes were undeserving. In vain, I look for photos of the old interior on the internet, and if there are none this is perhaps because it was as disappointing as I remember. What made the difference between the music hall and the auditorium I don’t know, but if we were likely on the music hall side it had balconies and a large open floor upon which had been set up portable seating. We were in one of the balconies on the right and had a good view of our mother who was on the right in the chorus. Augusta had turned out and the place was packed. I remember her as being in a new long black dress with a fitted waist and full skirt, or no it was a black sweater and less full long black skirt that she wore, the long black dress with the full skirt came later. With her jet black hair she looked elegant in all black with minor touches of costume jewelry. I was glad she had this, it was nice to see her involved. I also wondered if she actually sang during the performances or faintly exhaled the words because I swear I never heard her sing at home, at most she talked-sang with no projection, and from the audience she didn’t look like she was audibly singing she looked like she was blankly miming.

Three - 20

You can usually tell, even at a distance, if a person is singing and breathing and singing and breathing.

My mother had at first been against my auditioning for the Augusta Choral Society. She wanted this for herself, and I find it hard to blame her for looking upon it as her territory and guarding it, even then I didn't protest, but she changed her mind. As it was, I ended up not singing in the Augusta Choral Society, the director was of the school that felt to begin singing when young risked blowing out one’s vocal chords, which it can do, and she invited me to audition again when I was a couple years older. But I sang that summer at Brevard and if you really honestly sang, which we had to do, it was a relatively small a cappella chorus and there’s nowhere to hide one’s voice in an a cappella group, no room for mistakes, it was a workout. Singing in that chorus was also the best time I ever had in rehearsal and on stage because the conductor was every moment on top of and fine-turning every note out of each person’s mouth while also shaping the whole at once, which translated into my first exhilarating experience of impeccable unity in a performance. It was like leaping on an already moving train and if your time and breath failed you would go under the wheels. It was marvelous. After Remington left, my former violin instructor, Eloy Fominaya, took over the spot of conducting the Augusta Choral Society.

Attempting to loosely verify my memories of the the Augusta Choral Society and the Messiah and Good Shepherd (that I had indeed observed a nineteenth century Julia McKinne on a plaque), while combing through newspapers and other available information my attention was drawn to a video of an interview with opera greats Marilyn Horne, Joan Sutherland, and Luciano Pavarotti on bel canto singing, and from there I went on to spend a fair amount of time listening to Joan Sutherland’s high E-flats and E-naturals break the sky wide open, which reminded me of an absurd video I’d come across during my search. It was on the celebration of All Saints Day, a presentation made by a priest at the Church of the Good Shepherd, and had so much echo it’s difficult to dig through the bad recording for his words. By the magic of cheap special effects, his body is translated from standing before a black screen to a blue stairway that leads up to a great ball of light in a sky thick with blue and white cumulus billowy clouds as he talks about St. John’s revelation of the heavenly court with all the people of God in their unceasing praise of divinity singing “Worthy is the lamb that was slain”, relating St. John’s imagery to the communion of all those who have placed their trust in God who are recalled and united in All Saints Day and how though they are unseen one is in their fellowship with the eucharistic prayer at Good Shepherd as the ceiling opens (the background image changes to the angelic heavenly court with trumpets and tambourines, the painting being “Christ Glorified in the Court of Heaven “ by Fra Angelico) and the priest exclaims the whole company of Heaven is gathered with the eucharist’s celebrants, in one’s daily life one is as if at Sanford Stadium in Athens, Georgia, surrounded by the saints cheering one on to fight the fight and stay the course, attain the prize. Then he seamlessly transitions to recalling Handel’s Messiah and its good news of the existence of God and all made in God’s image, saved through Jesus’ embrace alone, the sacrificial love of the Lamb of God. He emphasizes the “alone”, which reminds me of how I was tossed out of that church at the age of seventeen, by the youth pastor, for being a heretic. I had remembered the congregation as strenuously WASP, which is an aesthetic into which

Three - 21

my family didn’t fit, yet there we were, and this priest’s bringing in Sanford Stadium of the University of Georgia and the celebrants of the Georgia Bulldogs football team as a metaphor for the gathering of the saints was right on target for representing everything they were and we weren’t.

Was I a heretic? The youth minister, who tried to act a buddy to teens like ministers in the movies, but always came off to me as being a failure of a double agent, like ministers in the movies, had one by one gone through the youth group asking what each person believed. We were meeting not in the parish hall but on the second floor of an old white wood building that had offices on the first floor, and the meeting room was quite small, barely large enough for the table around which we sat. As I’d been asked, I was honest and I said what I believed and he said I was a heretic and ordered me to leave and not return. In front of all the others I stood and walked out, age seventeen, some individuals I’d know for about six years. I thought it a weird spectacle to make of a seventeen-year-old in front of the other youth, especially as I reasoned likely a good many of the adult members of the Church of the Good Shepherd didn’t believe, many would have been agnostic, but no priest was going to ask each adult, from the Sunday podium, what they believed and then toss them out if they didn’t give the right answer, because the church needed their money. I was always in trouble for what I did or didn’t believe and so in that respect I was unfazed, but my expulsion seemed bizarre. The very uncomfortable part was the silence of my peers, but I should have learned by then that very rarely do one’s peers come to one’s defense when it involves publicly taking on authority or the majority. The priest wasn’t Father Clarkson, who served there from about 1942 to 1979. This was a younger man who arrived in the 1970s. The Church of the Good Shepherd, as with all other churches, doesn’t offer on their website a list of all their prior ministers, which strikes me as less to do with “we are about Christ, not any one minister” than “we don’t want to hear about your problems with any former ministers.” Which is too bad that I can’t find his name because I’d love to say who this was. By definition, I was an official heretic. I would have said I didn’t believe in a literal physical Jesus Christ and that I didn’t believe Christianity was the only path to God, I know I quoted a verse to back me up, it may have been 1 John 4:7, “…love is from God, and whoever loves has been born of God and knows God”, and I may have said I didn’t believe in a personal God, which I felt was covered by 1 John 4:12, “No one has ever seen God; if we love one another, God abides in us…” I probably said I believed one could be an atheist and could still be “of God” if one abided in love. That was my reasoning for church critique. I was surprised this profession got me called out as a heretic, also because this was the 1970s and what Episcopal church would kick someone out as a heretic in the 1970s? That bordered on witch trial fanaticism in the 1970s, when America’s churches were still reeling from and trying to figure out how to deal with Time magazine’s 1966 “Is God Dead?” cover.

Found him. I decided it would be unfair to me to leave him to lurk in the shadows, unidentified, so first I tried checking Episcopal sources for him and that failing I was able to came up with, in Augusta news archives, notices for Good Shepherd services in the 1970s that showed just enough info that I didn’t have to buy a subscription. He was Rev. Arthur Everett Johnson, who is reported in the 1973 Sewanee News for the Sewanee Academy of Sewanee, Tennessee, as having “completed a year’s clinical

Three - 22