TWO

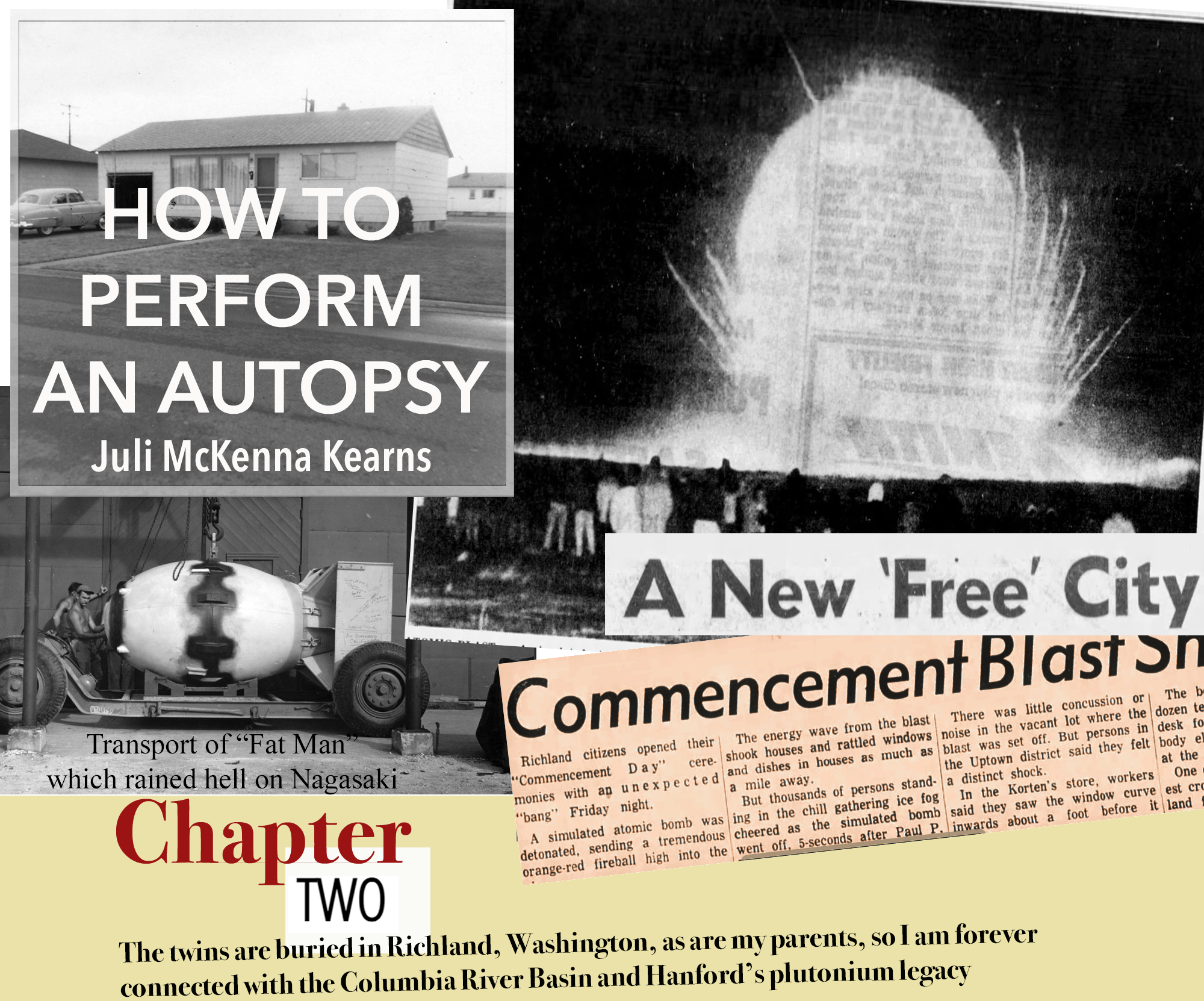

The twins are buried in Richland, Washington, as are my parents, so I am forever connected with the Columbia River Basin and Hanford’s plutonium legacy

1

Green sea turtles, after hatching from the eggs their mothers have buried in Atlantic coast beaches, are pulled across the sand by a magnetic attraction to the ocean, their little green sea turtle brains hardwired to respond to its siren song, and upon reaching the briny slosh and pulse of its waves make their way to a region of the Atlantic known as the Sargasso Sea, an area rich with brown algae upon which the turtles float, safe from predators, until years in the future another internal clock pings and they venture from the security of their seaweed womb into the ocean world at large. A number of videos are available online of the phenomenon because humans like to be witnesses to what is to us remarkable, even better if inexplicable, which the hatching of the turtles classifies as for a species such as ourselves that is born helpless and spends years being prepared for adulthood by family and society. En masse, sea turtle mothers having laid about a hundred eggs at a time then leaving them to their own devices supplied by their green sea turtle biology, the abandoned siblings bubble up out of the sand and flap flap flap their clumsy but effective front flippers pulling themselves and their portable keratin shell houses down the beach to the water that is their natural home environment. As I watch them in several of the online videos, the flippers act so much like wings that I find myself thinking of them as birds. Left only to our imaginations, we might picture them sedately swimming into the waves, when as they each reach its grip, in several videos I watch, the ocean instead seizes and tumbles them in. From a human point of view the reception can seem a violent welcome, but then life is hard, and though I read that close to ninety-two percent of the hatchlings will make it from egg to ocean, only one in a thousand will survive to adulthood, the bulk of that death toll due a predator higher up the food chain comprehending them as dinner. Even humans. Which is why the sea turtle is now protected under the U.S. Endangered Species Act, and their international trade is prohibited under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora. If I were stranded on a desert isle that happened to be host to a sea turtle hatchery, and I needed food and knew enough about sea turtle eggs to know when to watch for their hatching, as they bloomed out of the sands I would be amazed by the spectacle even as I caught and clubbed their cuteness for a meal. One needn’t worry about this prospective, however, as I know almost nothing about sea turtles and would only witness their glorious entry into the world en masse gallop to the ocean by pure dumb luck. Or, for instance, on YouTube.

Viewing the sea turtle’s emergence, what we can’t see is how, with a temporary “milk tooth” (so called to make comparison to the appearance of a human infant’s deciduous teeth when of an age to still be nursing), a carbuncle that will soon fall out after it fulfills its singular purpose, the buried baby turtles break out of their aragonite eggs (aragonite is like calcite but has a different crystal structure), then they must dig their way to the surface of the sand with which their mother had covered them, a task that takes three to seven days. A hundred million years ago they began their existence

Two - 2

as land creatures, that terrestrial heritage observed in their eggs being laid on land, as well their evolutionary migration to the sea evidenced in their scramble for the ocean the moment they surface the sands in which those eggs were buried. If this were a novel, one might now have a character mulling over how such births exemplify the struggle with the task master that is life beating one up from the beginning with the fact that life is hard, but just as you were programmed to be born, you are programmed for giving that life the old college try.

I don’t know when exactly I became aware of growing up, that I would not always be the same, because the “I” of myself seemed always the same to me, what was in me that made me wonder about the world, to want to know it, that examined my experience. In the eyes of a child, adults are such a different breed, it’s difficult to comprehend becoming one, even when you know you will, when I was three I would put on an old pair of high-heel shoes of my mother’s that she kept in my closet and would play at being grown up in them, but I also thought of myself as grown up but in a small body. If one has older siblings, or even cousins hanging about, perhaps it’s easier to comprehend growing up because you see them doing it, and you can anticipate becoming what they are. It may be very psychologically different looking to your older siblings on what it is to grow up, on how to or how not to grow up, than if one is the eldest and has only the adult world with which to compare oneself.

While we inherit instinctual compulsions that would seem as oddly unique to survival and insensible in their specificity as what drives infant green sea turtles into the ocean waves, we are so entrenched in culture and separated from such natural knowledge that for all intents and purposes we are born foreigners to this world and must learn everything either by the casual osmosis of observation or by applied study. Also, we are born utterly and naturally helpless, so that whereas a baby sea turtle follows the command of instinct in its immediate mobility, we are just as naturally intended to depend upon and bond with our caregivers, naturally built to trust them, to share sympathy and compassion, emotions that are fundamental to and part and parcel of the many intricacies of communication and bondedness we are taught and which we seek, and seek as well the rewards of approval that encourage our efforts at mimicry. We come to know what we know by our many ways of being taught, by both personal caregivers and by the broader community, concertedly, and casually, even unwittingly. By the like nature of their own infantile schooling, all these humans share with us the behaviors of what is commerce in the broadest social sense of the word, and the complex histories that are intended to tell us the whys and wherefores before we can form the most innocent and childish questions of context, so that before we know it the world simply is what it is and always has been. And despite and because of this, we learn to make comparisons and judgments that all arise from our most primitive demonstration of selfhood when we one day feel an injustice has transpired, we have been treated unfairly. Eventually we must, or should, determine the real function and utility of all we’ve been taught, and whether it was right and sane. Some feel so at home in their instruction they are comfortable where they are and by and

Two - 3

large accept it with perhaps some personal adjustments. Others may be compelled to, piece by piece, break it down, pry the machine apart, and examine the cogs and wheels of what seemed like truth, when they espie perhaps what might be the slightest tell that there’s a break in the system. We may realize something is wrong but then not have a right thing with which to replace it. We may not be able to trust what is right according to our own experience, because beliefs based on incomplete personal observation can often be in error, but we will know that something is wrong, the machine is not working as we’ve been told it should. Something in the machine itself tells us that it’s not working as it should.

Perhaps one of our most fundamental, perhaps even one of our first introductions to the machinery of the universe, that it works around us regardless of anything we or anyone does, is that the sun daily rises and sets. And so we learn to count our lives by days.

The sun does not revolve around the earth. Galileo, who supported what was then a theory of heliocentrism, rather than a proven fact, in 1633 was found guilty of heresy and placed under house arrest for the remainder of his life, under the reign of Pope Urban VIII. The truth was criminalized, but not necessarily because it was believed to be so wrong that Galileo should be imprisoned for it. It could be argued that Urban VIII knew that Earth was not the center of our universe, but to replace Earth with the sun was, at the time, on par with shoving humans off the pedestal that bore the congratulatory identification of Reason for Which Everything Exists. Pope Urban VIII’s rejection was less a matter of failing to understand how the universe works than selecting the model more beneficial to his situation as Pope. As early as 270 B.C.E. Aristarchus of Samos had proposed a heliocentric system. But even Martin Luther, former Augustinian friar (the emblem of the Augustinian Order is a fiery heart pierced by an arrow, reposed on an open book, suggestive of the search for both divine and earthly knowledge) and father of the Protestant Reformation, excommunicated from the RCC in 1521, was in agreement with Rome and took exception to Nicolaus Copernicus’ theories on a heliocentric system when in 1539 he reportedly said, while at dinner, that Holy Scripture attests Joshua, doing battle with the Amorite kings at Gibeon, told the sun to stand still, not the earth, and that’s that, proof positive the sun revolves around the earth and not the earth around the sun, or else Holy Scripture would have told us the earth was ordered to stand still. One wonders why this bit of history is attached to Martin Luther dining. What is the significance of this that makes it part of the story. But some hold that the Roman Catholic Church early on accepted the heliocentric system theoretically, however feeling the pressure of the Protestant Reformation they backtracked and so banned Copernicus’ 1543 “De Revolutionibus” from 1610 to 1835. It’s now difficult to imagine that in the early seventeenth century the common knowledge was still that Earth was the center of all things. Shakespearean audiences believed that the sun circled them as they sat in the Globe theater. As the sun revolved around him, Hamlet wondered over the philosophical question of to be or not to be. Difficult to imagine that when

Two - 4

Meriweather Lewis and William Clark were conducting reconnaissance in the Northwest Territory for America’s expansion to the west, “De Revolutionibus” was still banned, though the RCC in 1758 had made the determination it wasn’t heretical to teach heliocentrism. As our ancestors moved from the geocentric to the heliocentric model, perhaps there were some who couldn’t take easy passage on that ship and sailed off on their raft into a madness that was their abandonment by God, yet here we are, descendants of the survivors.

Did any of the ancients ever really imagine the sun was Apollo in his chariot with racing steeds or was this only always poetry? I readily confess that though I was early educated on the fact that the earth revolves around the sun, when I gaze up at the blue sky I see the sun as mobile, traveling from east to west throughout the day. That does not make it so. What my perception does reflect is my very self-centered human belief that where I live is the center of all things, but then when I view a night sky unvarnished by light pollution from cities, depending on which way the wind blows, I am either crushed or breathless with wonder at the grand panorama my human brain hasn’t the wherewithal to comprehend. The daylight sky anchors us to Earth as the main stage on which we conduct our lives and business. The night sky, away from street lamps and the gaudy brilliance of LED (light emitting diode) signs, tears away our protective walls and replaces confidence with questions. Even those generations who viewed the fixed stars as light entering through holes in the firmament, revealing the divine beyond, felt the disorientation of grand mystery.

We are not green sea turtles whose biologies can trust that the magnetic pull of instinct is carrying them to where they should be if they are to survive. Humans get ideas in their heads and construct worlds of supposed evidence to support them, which means that the essential instinct of humans is to believe that what they imagine to be true is right.

Humans can’t walk in a straight line. We believe we walk in a straight line but, without a point of reference, if there’s no sun or horizon to anchor us, we begin to circle and become lost. We place one foot in front of another and believe we know where we are going but don’t. If migratory birds have an inner compass that enables them to use the earth’s magnetic field to guide their flights north and south, we don’t have that. Maybe this is why a compass can be so peculiarly fascinating. Underlying our belief that we can walk a straight line if pointed in the right direction is a stronger belief in the little moving magnetic pointer of the compass. We are compelled to trust its arrow even if we know nothing about how a compass works, even if we don’t know what a compass is. There’s an arrow. Follow it. We trust that arrows always know where to go. We are constructed to instinctively believe in arrows.

A great portion of our lives is erroneous information, which is often nothing more than an innocent failure for someone to disseminate correct information, which is incorrect information that is spread about, and even one true account then creates a conflict of information, nothing nefarious about it, but without concrete firsthand

Two - 5

knowledge or sound documentation it becomes almost impossible to sort through varying accounts and conclude what information is correct. Or information may not be in error but different incomplete accounts give different descriptions that break up a thing and make it into something other than what it is. If the accounts are too spare they can generate different stories when people try to fill in the blanks, which is what humans often do, they attempt to make a fulfilling story out of one that has too few words, they try to force out of too few facts a history. And yet humans tend to also not like stories to be too involved. Most prefer a simple story and can take two facts and conjure a whole story in their mind that supplies everything they need to know about who did what and why and what should be done about it.

The great Columbia River begins in British Columbia, Canada. A website, which should know the facts, says the river’s origin is in Columbia Lake in British Columbia, but another website states that the Columbia River begins up at British Columbia’s Kinbasket Lake, when instead at Kinbasket Lake the Columbia River takes a dramatic turn to the southeast and travels 138 miles down to Columbia Lake. Tracing the Columbia River’s path on Google Maps, I find that where the river passes over the border from Canada into the USA, no town has cropped up to celebrate this transition. Despite this, nearby on Google Maps there is supposedly a Loblaw Pharmacy, which is odd as physical pharmacies invariably belong to towns. Loblaw Pharmacy turns out to be a little wood building, painted green, one door, no windows unless there is one on the riverside of the building which can’t be seen on Google Maps. The building is of a size to resemble a little railroad crossing shanty, but it doesn’t have windows looking out on the railroad that’s across the two-lane highway from it, and there’s no railroad crossing besides. There is no corporate sign observable from the road. This little wood building does have what seems a little white slip of perhaps signage by the door, the type that when you get close enough to read will either say “Closed for the Holidays” or may provide, as may be in this case, a small print official reassurance, for those who have perhaps been instructed to come here to pick up their drugs, that they’re at the right place, for I check also a map of “all pharmacies registered with the College of Pharmacists of British Columbia” and this little green closet of a shack is listed and given an address, which is right where this little green shack is. Next to its front door are wooden stairs that lead down to the river, maybe to a place where a boat can dock and a person can climb up from that assumed-to-be but unseen dock and either deliver to the shack or pick up from it medication. I don’t know. The story that the Columbia River began at Kinbasket Lake was wrong but appears to be right if you find it too preposterous that the Columbia River begins south of it, flows north, then turns south again. Where do you think you’re going, river? Why do you behave like a human who’s lost in the forest, but we know you’re not human as you do eventually make your way to the ocean. The little wood shack that is identified as a pharmacy looks like erroneous information, or maybe it is a Google glitch. Or maybe this little green building services the British Columbia side of the Canadian border as an outpost legitimately used by a pharmacy elsewhere to drop off drugs for people who live in the area. I don’t know. This tiny

Two - 6

little thing is a mystery. I made up a story to try to explain a mystery and I have no idea if I could possibly be right, and I could very well be wrong. Nevertheless, there is Loblaw Pharmacy.

Something something happened sometime somewhere. This may have happened but it may have been something else that happened. It looks like such and such happened according to this account, which differs from that account, and even if there’s a working camera in the vicinity feverishly documenting all activity that enters its field of vision we may or may not absolutely know anything.

Yet there are things we know to be true, and there are things we absolutely individually know to be true that perhaps no one else knows the truth about.

What is a thing we know that is true?

We know what the element of oxygen is atomic mass 15.999 u, atomic number 8, discovered in the eighteenth century, we know it is a gas, the most common element on Earth, and the third-most common element in the universe, beaten out by hydrogen and helium. Helium, though the third-most abundant element in the universe, is rare on Earth. Hydrogen, which the universe loves, is only 0.14 percent of the Earth’s crust by weight, but it is common in compounds, such as water, which is made of two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom, chemical formula H2O, hydrogen buddies up with carbon and is thus in all animal and vegetable tissues. These things we know are true and many truths about them have been discovered since they were first introduced as facts. While only elements up to the atomic number 94 exist in nature, plutonium being that 94th, many are synthesized so the periodic table of elements has 118 elements, with more still to come.

We know that the earth revolves around the sun and that the G-type main-sequence (G2V) yellow dwarf star which is our very own personal sun is about eighty-five percent hydrogen and fifteen percent helium and that it spends its time, every second of it, manically engaged in a process of hydrogen fusion that every second (“the duration of 9,192,631,770 periods of radiation corresponding to the transition between the two hyperfine levels of the ground state of the caseium-133 atom”, according to Wikipedia) converts four million tons of matter into energy, yet children interpret the sun as a happy, jolly Earth partner and draw it smiling down on them from above, because we are just distant enough from its blinding orb (“Don’t look at it! You can’t stare at the sun!”) to not be burned to a crisp by the largesse of its fire. I was one of those children who sometimes styled the sun with a smiling face, and I still rather think of the sun as a jolly partner for Earth. I have learned to not be too distressed by the fact that one day it will no longer be our smiling buddy, it will become an out-of-control red giant star and then fizzle away into a white dwarf star. These are things adults typically do not tell children out of the fear that a child’s mind would not be able to cope with the knowledge that their very own personal star is destined to burn itself out. At least I didn’t tell my son, as a very young child, that the sun will one day die.

Two - 7

I don’t remember being told, as a child, not to stare directly at the sun, yet I must instinctively not have done so because my retinas aren’t burned out, just as the retinas of most adults aren’t burned out though they were all once children out and about in nature, under the great ceiling of the sky, and they too must have instinctively not stared directly at the sun, for I know parents don’t universally, every one of them, tell their children not to stare at it else there wouldn’t be public service announcements yelling, with every solar eclipse, “Don’t stare at the sun! Wear special glasses!” One way or another we know that staring at the sun is a bad thing.

We know that a rose is a rose is a rose but the appearance of roses varies as there are three hundred species of them and tens of thousands of cultivars, which means that humans, loving roses, have greatly elaborated on them.

We love novelty.

Oh, that’s a pretty drinking glass. Oh, I like the sound of that band. Oh, I love the color of that sunrise. Has someone made it into a rose?

We think we know what a color is until someone who knows Pantone sidles up next to us and lets us know otherwise, or until we try to make sense of the color we’re told turquoise is versus its appearance as turquoise stone. I think I know what the color orange is, in so many shades and tones, but then my son or my husband will look at what I think is red and call it orange. I believe I see the same color they do but interpret it differently.

We grow up knowing that tomatoes are vegetables because that’s what we’re taught—right now go look up “pictorial vegetables chart” on Google and I guarantee you that the tomato will be included, it’s not on fruit charts—then one day a “fun fact!” crosses your eye that informs, “Tomatoes are a fruit!” Which they botanically are. And if you’re young enough your mind is blown. Wow.

In our apartment right now I hear a minor storm that has begun outside, perhaps becoming less minor by the instant, thunder coming closer, the rain beating on the metal of the air conditioner lodged in a window behind me and against the glass above it, now beating harder, and that my son, working on an animation, has just turned to look toward the window. His back is to me and he doesn’t know I’m writing about him. One of the people who lives upstairs is walking about. These are things I know as true until I call to my son and realize as he moves away from his drawing he’s not working on his animation after all, he’s deep into another project.

It is true that there are certain exact things sitting on my desk. I can see them, and as far as things not immediately seen on my desk I think I know what is there because this desk is mine, others don’t normally touch anything on it, we are proprietary in this household about our desks, and I believe I know what I’ve placed on it. But if someone removed one of these things to which I’ve not paid any attention in a while, I

Two - 8

may never notice it’s gone unless I need it. Ask me where it is and I will say it’s on my desk, though it’s not, because as far as I knew it was. My assumptions, in this respect, can’t be trusted, just like I can’t be trusted to walk a straight line due anywhere, point me down a sidewalk and within six feet I’m already starting to turn and walk into the person beside me or a telephone pole. To the best of my knowledge, I’ve always done this. If it’s because I’m neurologically off-kilter in ways that I don’t already know about then I’m fine with not knowing because I manage. I’ve sometimes attributed it to my having the same genetically wonky, off-kilter feet as my mother, though even worse than hers, a characteristic I passed along to my son, and I’m sorry about that though I’d no control over what genes he got.

As for me, I will also know something to be true but sometimes will replace that truth with erroneous information, as many will. I vacuum the floor but if someone calls and asks me what I’ve been doing I may say “nothing” because the vacuuming of the floor wouldn’t matter to them, it’s a household task that doesn’t merit mentioning. If I stand looking out the window and you ask me what I’m looking at I may reply “nothing”, when instead I’m taking in a lot of information everywhere I set my attention, I may be even taking in exceptional information and not know this, which is reduced to “nothing” because nothing may seem worthy of remarking upon, and I might be thinking about something other than what I’m looking at and that’s either not worth remarking upon or I don’t feel like remarking upon it.

I also outright lie, as many will. “How are you doing?” I’m fine. I also know when my opinion isn’t fact, it’s just my opinion, and sometimes my opinion doesn’t matter, I know it can change, and if someone asks me if I like, for instance, a new item of clothing they are wearing that they love, I might say, “It’s great,” because I need instead to look at it through their eyes and see what they see, which is also how one broadens one’s world a little, or by leaps and bounds, understanding it’s not all about your preferences. That’s not the kind of lying that is a harmful breaking of trust.

We compartmentalize and may lie for sake of privacy. Children lie as a process of developing independence, boundaries, a sense of self. We may lie because we comprehend that the person we’re speaking with isn’t trustworthy, they have ulterior motives that aren’t worthy of the truth.

Inadvertently passing along misinformation isn’t lying. I know I might very well hand out erroneous information if I don’t check my facts first, so I enjoy the technology of my little computer-phone in a pocket upon which I can look up available facts and maybe the facts I find are right and maybe they’re wrong, maybe they’re in good faith mistakenly wrong and maybe they’re carelessly wrong.

During my life, I’ve been told a lot of things were true, and to the best of their knowledge they may have been true to the person who told them, they were not lying. I’ve been told a lot of things were true that were also intentional lies or half-truths, and I have no way of knowing all the times this has happened but I trust people do

Two - 9

this a lot, out of a matter of convenience, because it’s less difficult, because they are protecting how they portray themselves, in order to sway opinion, in order to avoid a conversation about how things really are, to preserve one’s natural privacy.

The truth is sometimes what one or another, many or a few, might want not to know, and so people lie about it. And people deliberately manipulate the truth to conceal facts deserved by others.

There are people who whenever they open their mouths they lie, and they are not deluded, they are just liars.

I’ve been told things were true that were misremembered and not true. I misremember things as well. I end up thinking of a lot of things as being true when I can only actually say that much of what I’ve believed to be factual is only true to the best of my knowledge. Sometimes it doesn’t really matter what was true, though one ends up believing an untruth, because it doesn’t impact one’s life. Other times it does matter, but telling the truth, or the truth that one knows, takes time, and that can be very boring to people. It’s too much information. They want the world compressed into a single easily consumable bite. They don’t want a history even though the truth takes time. One condenses and the truth becomes anemic and open to interpretation.

Because I don’t know with certainty some of the basic facts about my life or the lives of my parents, what I’ve been told, today I’m searching the internet hoping to learn how 1950s child safety locks for car doors were installed and how they worked. I come across one that is being sold on eBay, a museum piece still in its packaging, a 1950s child safety lock for AMC, Chevrolet, Pontiac, Ford, Mercury, Dodge, and Chrysler models. Pictures of the packaging are supplied, and on the back are instructions in blue print that tell me little about how these locks, which require no drill, only a screwdriver, are installed. Slightly more informative is a blue and red illustration on the front of the white packaging that pictures the mechanism as attaching to the main gutter of the door in seconds, the device shown on the outside of the car where the door meets the roof. One locks the door by turning the instrument from a horizontal position to a vertical one. Thus positioned, crossing where the door meets the roof, the item prevents the door from being opened from the inside. I will assume that a part of the mechanism on the interior has also turned horizontally. Above and to the left side of this is an illustration of a child of maybe seven to ten years of age lying face down on a street while the car from which the child has fallen speeds on, the driver and passengers apparently oblivious, or perhaps a faded portion of the illustration shows a passenger in the car who looks back in astonishment. I can’t say with perfect knowledge one way or another because the visual information has deteriorated.

A black-and-white photo from June 1958, in Lawrence, Kansas, shows my father on the left, and my mother holding me, standing beside him on the sidewalk before their car. I’ve always assumed they were standing before the apartment building in which

Two - 10

they lived, facing it, and that the house behind them, as seen in the photo, was directly across the street from the building. I’ve always pictured them facing the apartment building for the photo and the person who took the photo thus capturing the other side of the street. I’ve always connected the photo with our being about ready to leave Lawrence and this is like a “so long” shot. However, when I check Google Maps, I find that the background is not, as I’d supposed, the house opposite the apartment building. This large white house with a front porch, across the street from where they stand, is on a significant enough rise that it’s approached by three tiers of concrete stairs overgrown with grass. A Google Maps view of the side of the street across from the apartment building in which we lived in Lawrence, Kansas, shows an old house with a front porch but it is level with the street, as are the neighboring houses. So, I don’t know where the photo was taken after all. My father is dressed in an immaculate white shirt, the sleeves rolled up, and wears light-colored trousers, probably a light beige, held with a narrow belt. His shirt and pants are perfectly ironed, permanent press not yet available, which testifies to the truth of my mother’s expertise at ironing, of which she sometimes spoke with some pride, especially in the case of a company of famous flamenco dancers whose costumes she ironed, which were difficult, and she was precise as a surgeon. I’m in a little sun suit, both my socks stretched out at the toes by about three inches, and I lean away from my mother to look up with an open-mouthed smile at the photographer, recognizing our photo is being taken and responding. My mother’s hair is growing out from her pixie cut she got after my birth. She wears an awkward-looking pair of dark shorts and a long, loose short-sleeve shirt buttoned up to the neck. I am almost a year old and don’t know she is about five months pregnant. This pregnancy follows my birth so closely that one might wonder if it was accidental, but she never indicated that it was.

The rear door of the car doesn’t appear to show a safety lock, but the door is also partially blocked by my parents.

I now turn to a black-and-white photo of the car in the driveway of our first Richland home, developed in April of 1960. I stand beside a girl who is about three years older than me and she embraces a box of Cracker Jack caramel-coated popcorn and peanuts from which she shares about two bits of popcorn with me. Near us is her toy baby carriage she has wheeled into the yard. I’m in a light-colored short-sleeved dress, and she’s in a striped dress with a thick sweater over it, so there’s vaguery about the weather. Her little brother, about my age, is a blur rushing into the picture’s frame from the lower left corner, and I know he’s eager to get some Cracker Jack as well because a second picture depicts her doling out a little to him and grinning big for the camera as she does so. I remember this incident probably because it involved Cracker Jack, and I felt as though she was a little stingy with the candy, the way she parcelled out just a couple of bits for me and her brother, but then it was very easy to want the treasured box of Cracker Jack all to oneself. I wasn’t yet three years of age and she was a little too old to play with a younger child without being bossy, which could be off-putting, but I considered her a good friend. Her little brother I thought

Two - 11

of as infantile as he only communicated with grunts and hand gestures, wore what I looked upon as childish overalls, and I was irritated with children my age who behaved as though they were children. He once walloped me in the mouth with a toy gun, not accidentally but intentionally, because it was the kind of thing he would sometimes unexpectedly do, as if he was unable to control his emotions yet, and when I went crying to my mother about it she told me I was a crybaby, she wasn’t going to fight my fights for me and demanded I go back out and whack him, then was mad with me when I instead went out and, having found he’d calmed down, returned to playing with him because I didn’t want to hit him, I wanted to be friends. Not long before we moved to Seattle he gave me something he’d found in the back yard, the kind of mysterious little thing one finds by chance, a discovered thing, which becomes a prize, and when he handed it to me I realized he liked me, he wanted to please me with a gift of a thing that was special, and I thought of this as my first boyfriend-girlfriend interaction. Whoever took the several photos of us sharing Cracker Jack surprises me with the third photo as they have taken the picture from above, which means they have climbed up to stand on the front stoop in order to get this perspective. They were trying for a photo that told a story about the three children with the Cracker Jack. They had made an attempt to be creative and I would wonder if it was my mother but she hated taking photos, she didn’t like working the camera, she didn’t like framing up a picture.

The reason I looked at these several photos was to see if there was a child’s safety lock on the car door, and there’s not.

2

Everyone needs a crisis within their first year of life, and mine was one that became confusing as there were at least three very different versions of it and I will never know which of those versions is true.

That we move from Lawrence as soon as my father graduates from the University of Kansas means that he would have been applying for jobs before his graduation, and landed one with the pockets to pay for a moving van to carry their apartment’s belongings across the Kansas plain, over the Rocky Mountains, to Richland, Washington, nearly seventeen hundred miles away, a place at the confluence of the Columbia and Yakima Rivers, far removed from any large cities, such as Seattle to the northwest, Portland to the west, Spokane to the north, and Boise, Idaho, to the east. In the semiarid desert way down in the southeastern part of Washington State are the “tri-cities” of Richland, Pasco, and Kennewick. Richland is on the west side of the Columbia River and above the delta formed by its conjunction with the Yakima River, the source of which is the Keechelus Lake in the Cascade Range near Snoqualmie Pass, the Yakima flowing down from the northwest to join with the Columbia slightly below Richland. Pasco and Kennewick are below the delta. A little further below Pasco

Two - 12

and Kennewick is where the Snake River also flows into the Columbia, its path having taken it from Jackson Lake in Wyoming through the Grand Tetons and Idaho. With the contributions of these two major tributaries the Columbia begins its gentle curve to the west so as to create the border between Washington and Oregon States in its grand push to the Pacific Ocean.

If I now describe the rivers and their geographic relationship to the towns that sprang up around them, it’s because when I lived among these rivers I thought of them as vital forces that shaped everything about our lives, and greatly impressed with them forever moving on to elsewhere, far away.

Above Richland, about nineteen miles to the northwest, is the Hanford Project, which is also called the Hanford Site, and during WWII went by Hanford Engineer Works (HEW). A reason that area was selected for the Hanford arm of the Manhattan Project, during WWII, is because they needed plentiful hydroelectric power, and a lot of cold water was going to be to cool the reactors. Also, they needed to be located far away from major population centers.

After WWII, though everyone knew about the Manhattan Project, The Bomb, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, very few people knew about Richland. When we later moved far away from Richland to Georgia and I told others about Richland they would look at me askance, not believing. They might even say, “No, that can’t be,” but it was, they simply hadn’t heard about Richland and its role in the Manhattan Project and they believed they would have heard about such a place if it really existed. When I told them about the whole-body counter through which Hanford ran the schoolchildren of Richland, gathering information on radiation accumulation, I wasn’t believed. When I related that my father had conducted radiation experiments on miniature pigs, and that we had reason to worry about Hanford not being forthcoming about radiation leaks, adults would tell me, “You’re making that up.” They didn’t want to believe because they wanted a simpler world than what Richland was, they wanted to think there weren’t secrets as big as towns. They didn’t even know Washington State held a semi-arid desert and found that almost as impossible to accept. It gets tiresome being told, “You’re making that up.”

Richland began as a secret place, and its origins in secrecy stayed with it even when it purportedly became not secret, but was still secret enough that decades would pass before important information about Richland and Hanford began to be declassified and released, facts that caused the part of the public that was attentive to recoil in horror.

Richland isn’t exceptional in that everywhere has its own pockets of secrets. People will accept that their workplace has its own behind-the-scenes secrets but don’t understand how everywhere people gather there will be the formal facade for public consumption that covers up what’s under the counter. This doesn’t mean that what’s under the counter is toxic, but there are many situations in which it is. In the case of

Two - 13

Hanford, the behind-the-scenes facts were toxic, endangering the Columbia River Basin with nuclear waste leaking into the groundwater from tanks that had been built to last only ten to twenty-five years.

Between 1940 and 1950 the population of Kennewick grew from 1918 people to 10,106, a 427 percent increase. Between 1940 and 1950 the population of Pasco grew by about 161 percent, from 3913 people to 10,228. Between 1940 and 1950 the population of Richland grew from 247 people to 21,809, an increase of nearly 8730 percent.

Richland and Hanford, built far away from civilization, in 1945 was the second-most populated city in Washington State with 50,000 people who had gathered to labor for the war effort. It was a secret place, despite the Hanford site occupying roughly 600 square miles, and what everyone was doing there was a secret, even to the majority of the people who lived and worked there.

That kind of dramatic increase in population immediately tells you a lot about Richland and Hanford. In the old west, gold rush towns exploded in population because the secret got out that here was gold and people came flooding in hoping to get there in time to grab a piece. Richland was a secret and still it exploded in growth, with people drawn there for the singular purpose of manufacturing the plutonium that was needed for Fat Man, the bomb dropped on Nagasaki on August 9th, 1945 at 11:02 a.m., immediately killing 35,000 to 40,000 people, ultimately 60,000 to 80,000. Because of Little Boy, dropped on Hiroshima on August 6th, Nagasaki became a kind of afterthought in history as it hadn’t the privilege of being the groundbreaking first. John Hersey wrote a book about Hiroshima, called Hiroshima, which is a great book, I highly recommend it, and Nagasaki retired further into the shadows because humans are taught to think of everything as a contest and if you don’t get first place you’re a loser. Nagasaki hadn’t even been the destination of Bockscar, the plane that delivered Fat Man. Nagasaki was the second option in the case that the primary target, the city of Kokura, wasn’t accessible. Nagasaki was almost not accessible because of cloud cover, but then a hole opened in the clouds and the crew of Bockscar would have felt they were lucky.

Up to the end of WWII the majority of those who worked at Hanford were only aware they were laboring on something for the war effort, not knowing what. People had cover stories. A stranger might ask you on the bus what you did for work and your cover story was that you made shoes. If you didn’t tell your cover story and you were talking to the wrong person then you were in trouble and out of work. Signs were posted everywhere reminding one of the importance of secrecy. At the end of WWII, the people of Richland learned they had built the plutonium for Nagasaki, which became the identity of the town. In the summers they had an Atomic Frontier Days festival and parade in which they portrayed themselves as pioneers of the atomic age. A 1954 photo shows a float upon which the GE (General Electric) Plastic Man, in his radiation protection suit, shakes hands over a fence with the male representative of two twentieth-century settlers in western farmer-cowboy attire. Plastic Man, looking

Two - 14

much like an alien visitor from a 1950s sci-fi film, stands on a black-and-white checked floor, the pioneers on turf backed by two tumbleweed bushes. Well, wait, I need to make a correction. When I look at the photo again I remember it doesn’t show them shaking hands, but one knows from the dynamics and messaging that they did shake hands and that the photographer didn’t catch that moment. The float reads “Where the Old West Meets the New” and “10th Anniversary Start-Up of the First Hanford Reactor”. After WWII there now came to Hanford people who knew what had been worked on and had other work with plutonium to do and other secrets to maintain during the era that was the Cold War.

Sometimes I have the feeling that my father gravitated to Richland and Hanford because it was a secretive place and he knew how to keep secrets. A manageable life was one in which everyone trusted in secrecy. He may have intuited that where secrecy is prized, it may be acceptable in all areas of one’s life. Secrecy was his basic mode of operation because he never talked about anything, and that need for secrecy was imparted to me, so that eventually when I wanted to tell even a little bit about things that shouldn’t be secret, I tried to do so in a coded way if it was personal, because if I said even the littlest truth about our lives the internal psychic slapback was so profound that I’d feel ill.

My father would have had, of course, security clearance to work at Hanford, everyone had some degree of security clearance, but I don’t know what level of security clearance his was, whatever was appropriate for his radiation research.

I look at a website that has one of the secrecy signs, an example that would have been put up after WWII, because there were still things to be secret about but that the area’s business was one of plutonium production wasn’t one of them else the billboards wouldn’t reference “chain reaction”. The text on the roadside billboard is “LOOSE TALK, a chain reaction, for ESPIONAGE.” The accompanying image is a diagram of what is called an uncontrolled nuclear chain reaction, the type that happens in nuclear bombs. The sign reads like attention-grabbing tips were drawn from advertising for Hitchcock films. Immediately below the sign on the web page is the header “Manhattan Project Locations: Oak Ridge, TN.” The page concerns an interview with a counter-intelligence agent who worked at Hanford and a woman who worked in classified files at Oak Ridge. The website is run by the Atomic Heritage Foundation whose business it is to collect and frame information on the Manhattan Project for the public. The sign, which appears to be identified as in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, was instead, as pictured in the photo, located at Hanford. When information was first being declassified about Hanford and put online on an unnecessarily unwieldy government website with almost no search functionality, I spent some intensive time trying out search terms to learn what was likely to yield interesting results and collected about 850 pictures from Hanford and Richland that were human interest rather than the construction of the reactors. I gathered pictures of parades, safety and fire prevention campaigns, the Hanford trailer city and environment, the secrecy signs, Hanford at work, Hanford celebrating Christmas, the numerous prizes and awards that were dispensed in an effort to build community

Two - 15

spirit, vaudeville entertainments, talent shows, the building of Richland, Atomic Frontier Days festivals, Tony the Atomic Clown and his miniature circus, the artists of Richland, not just wartime but early Cold War life in Richland. The photo of the “LOOSE TALK, a chain reaction, for ESPIONAGE” sign was one I dug out of the repository and posted, along with all these other images, on my photography site on Flickr along with DDRS (Defense Data Repository System) details, because identification matters. The document date for this image was 11 February 1954. The description was “Security Billboard on Area Highway.” Its document number was 7653-2-NEG, and its accession number N1D0027007. The picture shows the tumbleweed semiarid desert of Richland partly covered in snow. It is obviously not Oak Ridge, Tennessee. Oak Ridge is not in the desert.

A place is classed as a desert if it receives fewer than ten inches of rain a year. The yearly average for Richland is eight inches of rain whereas the yearly average for the United States is thirty inches a year. While looking at photos of how Richland currently appears, taking in how it currently sees itself, I came across one website that has described Richland as getting a lot of snow and one has to wonder what their definition of “a lot” could be.

A project my father would have been working on in the late 1950s would result in the paper “Zinc-65 Metabolism and Dosimetry,” authored by my father and Roger O. McClellan, introduced by Leo K. Bustad, out of Hanford Laboratories, presented at the 8th annual meeting of the Radiation Research Society in San Francisco, California, May 9th through the 11th in 1960. Six rams (you know, as in male sheep) were used to “determine gastrointestinal absorption, rates of uptake and turnover in the major tissues”. The National Isotope Development Center states that because of its gamma- and positron-emitting properties, zinc-65 is an isotope “commonly used as a tracer in physical and metabolic studies”. A 1959 paper by R. W. Perkins and J. M. Nielsen explores the absorption of zinc-65 in foods and people, the abstract of the paper noting that trace amounts of zinc-65 were disposed of in the Columbia River via Hanford reactor effluent water. This water, used for irrigation, meant a concentration of the radioisotope in humans via farm produce. Both authors were with the Hanford Laboratories Operation, General Electric Company, in Richland.

At Shechem is where the Biblical Abram came to the great tree of Moreh and received the prophecy that the land would be given his offspring, for which reason he built an altar there. The land was then ruled by a king named Abimelech, who took Abram’s wife, Sarah, for his own harem, unaware that Sarah was married to Abram as Abram represented her as his sister. Abram is excused for handing Sarah over to Abimelech as he thought if he didn’t he might be killed for her, but because Sarah was destined to only have a child by Abram, Abimelech’s house was thus cursed and he was temporarily made barren. When Abimelech rebuked Abram for having lied to him, Abram asserted he hadn’t as Sarah was his half-sister, they having the same father but a different mother. Abram’s grandson, Jacob, settled at Shechem and purified his house from “strange gods” by burying their idols under the oak. In the Biblical Book of

Two - 16

Judges, 9:45, is recorded the destruction of Shechem by yet another Abimelech. “And Abimelech fought against the city all that day; and he took the city, and slew the people that was therein, and beat down the city, and sowed it with salt.” The sowing with salt devastates land so that it becomes unusable for farming. Sowing with salt can also be considered a purification rite. A “salted” nuclear bomb is one that is designed to be a radiological weapon with an enhanced level of radioactive fallout that would make a large area uninhabitable. Zinc has been proposed for such a device. Wikipedia states that “A jacket of isotopically enriched zinc-64, irradiated by the intense high-energy neutron flux from an exploding thermonuclear weapon, would transmute into the radioactive isotope zinc-65 with a half-life of 244 days and produce approximately 1.115 MeV (maximal extractable value) of gamma radiation, significantly increasing the radioactivity of the weapon’s fallout for several years. Such a weapon is not known to have ever been built, tested, or used.”

Some of the other projects my father worked on produced papers with such names as, “Plutonium Metabolism in Miniature Swine”, “Preliminary Observations on the Biological Effects of Strontium-90 in Miniature Swine”, “Metabolism of Strontium-90 in Miniature Swine,” “Bone-seeking Radionuclides in Miniature Swine”,“Dosimetry of Cæsium-137 in Sheep”, and “Effects of Dietary Calcium on the Metabolism of Strontium-90 and Calcium-45 in Ewes and Suckling Lambs”.

Sinclair Bio Resources produces miniature swine for scientists. It currently lists four “options” of miniature swine: the Sinclair, the Hanford, the Yucatan, and the Micro-Yucatan. I’m going to assume that the “Hanford” swine is named for Hanford and is the kind upon which my father experimented. Exploring the Sinclair Bio Resources website further I find that my assumption is correct, the background on the breed is that the development of this swine began at Hanford Labs in 1958, the year we arrived there, beginning with two Palouse gilts and one Pittman-Moore boar, later adding more Pittman-Moore and a Louisiana Swamp hog that further reduced their size. The animals are guaranteed to be socialized.

We arrived at Richland—from where my father would Monday through Friday take the work bus out through the desert to Hanford to conduct experiments with radioisotopes on creatures such as miniature swine—in a 1952 Chevrolet Deluxe Styleline 4-door sedan (see Wikimedia Commons for a picture of the exact model). It took me forever, or a day’s research, to pinpoint the make of our car, which I remember as we still had the car in Seattle, and though I well recollected the chrome divider down the center of the windshield, and how it was a beautiful Twilight Blue (code 477), I had to rely on the Cracker Jack photos of it for identification via those photos showing chrome gravel guard accents next its front and rear wheel wells and its five-tooth grillwork.

Or rather, I should say we arrived at Pasco, living for a short while in a furnished rental where my first birthday was celebrated. Five photographs document that June event. The kitchen and dining room form one large room in a furnished apartment

Two - 17

that would have been modern for the time. In the dining room is a built-in bookshelf with various shelf arrangements, including cabinets, one into which the heater for the room is set. In one of the photos we’re granted a view to the left of the hall that interrupts the wall where the dining area shelving stops and we see the kitchen begins on the other side with white cabinetry at bottom and shelves above, a roll of paper towels on display on the counter, the dish towel rack empty. The dining room table is the style with a Formica top and steel tubing legs, the vinyl cushioned chairs also having steel tubing for legs. Seated in a child’s booster seat that has been tied to the chair with string, attired in a little dress and baby shoes, gesturing toward the kitchen, in the first photo I start out happy enough; in the second photo I face the camera looking a little confused about either the prospect of a cake or the concept of celebrating a birthday; my mother helps me cut the small cake with a large cake knife in the third photo; in the fourth photo, seated the length of the table from me, she leans forward to guide a forkful of cake to my mouth, two tall half-glasses of milk now on the table; by the fifth photo I’m sobbing, the camera person’s thumb accidentally, partly blocking the scene. Which would be my father. My mother, looking good, is increasingly heavy with the pregnancy with the twins as indicated by her maternity shirt. Otherwise she remains slender. She elects to wear shorts and slip-on sandals, which was standard summer fashion for her.

This is the apartment where, as I remember it, I learned the left-behind cat had starved to death in the apartment in Lawrence, Kansas. When we arrived in Richland, we would have temporarily stayed at a motel or hotel before living in Pasco while we waited for housing in Richland.

Driving into Richland from the south one crosses the bridge over the Yakima River, and going north on George Washington Highway it used to be that one of the first signs of Richland civilization was The Desert Inn on the right side of the highway, the inn composed of a central two-story building with two long two-story wings extending left and right from it at maybe a fifteen-degree angle in a V formation. Its first incarnation in 1944 was transient housing for Hanford workers, then several years later became what was still Richland’s only hotel in 1958.

The Desert Inn was one of the places where my parents went drinking, the posh place in town, though it used to be government housing, and it bears some remarking upon due its social place in the community. To my memory, I never was inside The Desert Inn so can’t say what it looked like, but one of the Hanford Declassified photos I came across shows a woman in a form-fitting, glittery evening gown, shoulderless, the bust bedecked with “flames”, glittery mask over the upper part of her face, head crowned with a tall “flaming” cap of material that matches the dress (we should imagine this fabric is fiery red), and I’ve always assumed that the room Miss Flame of Fire Prevention Week 1950 is shown entering, guided by a man in a suit who holds her hand, must be at The Desert Inn, because part of a servers’ station, and a couple of round bar tables make it into the photo, and there stretches across a wall beyond

Two - 18

them a desert mural, which oddly enough doesn’t depict the Richland desert, they’ve chosen to make The Desert Inn’s patrons feel they are in the desert southwest of Arizona, the area’s hills and monumental rocks similar to Apache Junction, saguaro and yucca cactus featured, the story focus of the mural being a number of cowboys gathered around a corral fence to watch the battle between a bronco buster and a writhing, bucking horse. What other establishment in Richland during that era will have a mural but The Desert Inn? I turn to the Tri-City Herald and find in 1949 a picture showing a portion of what appears to be the mural, identified as in the dining room where the manager of The Desert Inn, Wally Bowen, is seated with a woman at a table before it, where they discuss plans for “Hello Neighbor Day”. Why “Hello Neighbor Day”? Because Richland was made up of people pulled in from all parts of the country to work at Hanford and there was no natural, home-grown neighbor and family network. The article is on how the hotel is the “crossroads for civic and social functions” and one of the most modern transit hotels in that part of the country since renovations and redecorating performed in 1948 when its 112 rooms ceased to be housing quarters for General Electric and the Atomic Energy Commission, Vance Properties taking it over, which still needed approval from General Electric for their plans. Telephones were added to the rooms, and the hotel was equipped with banquet rooms, a cocktail lounge, Art Williams Barber Shop, Dent’s Candy Store, and a terrace that overlooked the Columbia River at its rear. Another 1949 article is on the opening of the “Corral Room”, Richland’s first public cocktail room, and the adjoining banquet room called “The Round-up Room”, both decorated by Richard Lytel and Associates of Seattle, so we know who was responsible for the saguaro cactus mural. On the ceiling was painted a cloud with a silver lining, the floor was covered with a “dandelion speckled” carpet (as if an in-joke, as Richlanders fought to exorcise from their lawns this wildflower that in the middle of a grassy green carpet became a weed), leather and copper craft was used throughout, the bar chairs and tables were of hickory wood, and “cowboys perched on a genuine corral fence”. A 1958 advertisement relates the hotel has a cafe, dining and banquet rooms, cocktail lounge, and swimming pool. In 1961 the facade was given a new brick, stone and stucco facade, balconies were added to the second-story rooms and outside entrances given the first-floor rooms. Pool-side cabanas were soon added. All of this is precisely the kind of news that should be reported in every community, plus coverage of every meeting and event, no matter how minor, who decorated what, even the 8 May 1949 opening of the thirty-seat cocktail lounge was reported in-depth, every person who was there, what each woman wore, if a dress was designed by a Richlander, who played in the small lounge act that night, and the fact impromptu entertainment was supplied in the form of a bellman performing a tap dance routine. There was also a new exhibit of art in the lobby. If it happened it was there in the Tri-City Herald of that era, and The Desert Inn, billed as one of the best hotels in the Pacific Northwest, was where a lot of it was going to happen, from fashion shows, wedding receptions, church breakfasts, and meetings of local organizations, to regional conventions and conferences. In 1948, the Arctic Fur Company even opened a store in the hotel’s lobby, pending construction of a permanent location, hours “12 Noon Until 8 P.M.”. In May of 1949 General Electric

Two - 19

authorized Vance Properties Incorporated to sublet that space to the Kennewick Flower Shop. I think it was when I was about to turn eight that my mother promised my treat for that birthday would be a visit to the cocktail lounge at The Desert Inn where I would get to drink a virgin strawberry daiquiri, which I thought sounded extra magical birthday special, I loved strawberries, which we perhaps had as a once-a-year treat, and it had never occurred to me before I’d be able to do anything like visit The Desert Inn, much less experience the thrill of its cocktail lounge. I waited, excitedly anticipating the visit to The Desert Inn’s cocktail lounge, but my birthday came and went and nothing happened, the excursion wasn’t mentioned, there was no visit to the cocktail lounge. My mother brought it up again before my ninth birthday, again promising I’d be taken to the lounge at The Desert Inn where I would have a virgin strawberry daiquiri, she said she loved strawberry daiquiris, that I would love the strawberry daiquiri too, it was the best drink in the world. And I waited and waited and it didn’t happen, I think she was in the hospital again, which sounds like a good excuse for the promise not to have happened, but it was more a matter of very few things ever being promised, and the very few things that were promised never happening. I waited two years for that frozen strawberry daiquiri and when we left Richland in 1967 I had yet to visit the lounge at The Desert Inn or have a virgin strawberry daiquiri or ever step inside The Desert Inn at all (obviously this was a huge disappointment to me as I still remember it so well). The old hotel was torn down in 1968 and replaced by Vance Properties with a modern hotel, Joseph Vance had made his money off the Vance Lumber Company, sold the lumber company in 1918 and moved over into investing in real estate and developing commercial properties, he was still alive in 1948 when Vance Properties bet on Richland, the plan had been since 1948 to turn Richland into a resort area, a sunny vacation spot easily accessible to people from coastal Washington, presumably they would want a break from all that rain. And if you were going from eastern Washington to western Washington, as part of their friendly customer service, The Desert Inn advertised an easy experience booking rooms in Seattle from its desk, no doubt at one of the hotels owned by Vance Properties.

I’d say that I think The Desert Inn was named as it was to make you feel you were in Las Vegas, though without the gambling, except Las Vegas’ Desert Inn Hotel didn’t open until 1950. But ground for it was broken in 1948. Or maybe they wanted to call to mind the Desert Inn resort in Palm Springs, California.

As for the mystery woman who played Miss Flame in 1950, during the week of the beware-of-fire festivities, which involved her participation in fire prevention presentations at schools and other venues, the citizens were supposed to guess who she might be, the newspaper supplying clues and the rules for submitting guesses. The full clue given in the paper for Miss Flame’s identity had been, “A tree plus three is part of me. A star then blew the heaven. A step, a stop a beaming light, waste not, plus type 11. The bears, and buoys, my teenage toys, a life of quick gyrations. Grace and poise, a woman’s joys made lucerne my relation. With music’s beat we place our

Two - 20

feet with training and talent in our possession. We enchant them all, short and tall, I and ire Prussian.” On October twelfth, Dr. Stop Fire had been the master of ceremonies for a fire prevention program given by third and fifth graders, at the end of which “the mysterious Miss Flame” appeared, the riddle was read, and I’m sure that the children enjoyed the fact they had no chance of winning as they had no chance at all of making sense of the clues. On October thirteenth, the Lady from Safetyland (a founding member of the Richland Players and Richland Light Opera) announced their radio show would have its own Fire Prevention Week contest, the winnings of which, donated by Richland merchants, would be: a little black cocker spaniel puppy; five one-year subscriptions to comic books; five crayon sets; five cartons of candy bars; five gift certificates good for twenty-five ice cream cones each; ten automatic lead pencils; and three leather zipper loose-leaf binders.

Of everything that went on in Richland, I’m unclear as to what was “official” Hanford, as in government planned community relations, and what was purely public sector. For instance, the Lady from Safetyland is mentioned in a Hanford Works monthly report from January 1951, in the part on Employee and Community Relations Divisions, it being noted that amongst the many news releases made to local and regional news on various activities, press on the show had been sent out. Also, under Employee Information - Women’s Activities, content of the women’s pages for Hanford Works News during January 1951 included, “The story of Bette Szulinski and how she creates her songs and stories for youngsters as The Lady from Safetyland was featured January 12 along with the General Electric Consumers Institute recommendations for cleaner washes.”

Bette’s husband, Milton J. Szulinski was an engineer with the Chemical Technical Division at Hanford. The Lady from Safetyland stories were reproduced by the National Safety Council and aired on more than 480 stations. In the Hanford Works Monthly Report for July 1950, under Employee and Community Relations Divisions, Public Information, Radio Programs, appears the note that “Lady from Safetyland, a Public Functions and Services production, is now a weekly feature of radio station KALE on Saturday afternoons at 5:30 PDT, and is providing real interest for children ages 4 to 9.” A 1951 January news story states they were produced by the Richland Safety Council. A September 1950 report is a little clearer on provenance, giving the shows as produced by the General Electric Public Relations and Services Group, and sponsored by the Richland Safety Council. Since 1946, taking over for DuPont that had administered Hanford for the Manhattan Project, General Electric had been administering Hanford and Richland for the Atomic Energy Commission. The Hanford Works Monthly Reports had on their front page, “Hanford Works, Richland, Washington, Operated for the Atomic Energy Commission by the General Electric Company under Contract #W-31-109-eng-52.” The town did not become self-governing until 1958.

Not at all intending to diminish Bette Szulinski’s achievements, but I would imagine

Two - 21

that having General Electric and the Atomic Energy Commission behind the show aided in the success of Lady from Safetyland and its ability to make the leap from Richland listeners to stations all over the nation.

In 1950, the novelist, Kurt Vonnegut, was employed by General Electric (see census) as a writer, and the Hanford Works Monthly Report for June 1950 notes, under Employee and Community Relations Divisions, that “A very light compliment considered especially noteworthy was paid to the staff of Public Functions and Services by Mr. Kurt Vonnegut, Project Supervisor of 1950 Island Camps for the photography and art work prepared for the presentation of Dr. W. I. Patnode.” I wonder if the “Island Camps” concern the Marshall Islands, maybe Bikini Atoll where nuclear testing, under Operation Crossroads, had begun in 1946, lasting until 1958, the most significant event being the detonation of Bravo in 1954, but I could be wrong. Kurt Vonnegut would not have his first novel published until 1952, but in February of 1950 had his first short story published in Collier’s magazine, “Report on the Barnhouse Effect”, for $750, which would be close to $10,000 today. The story is about a man who discovers he has the power to affect physical objects and events through the force of his mind, which he calls “dynamopsychism”, and when the US government learns of this it tries to make him into a weapon, for which reason he goes into hiding. While in hiding, he destroys all nuclear and conventional weapons stockpiles and military technologies. Kurt Vonnegut quit General Electric in January of 1951.

Miss Flame’s identity was revealed at a variety show at the end of Fire Prevention Week. In the paper, a photo (which also appears in the Hanford Declassified archive) from a performance capping Fire Prevention Week’s activities accompanies the statement that Thelma Hays is the mysterious Miss Flame, who holds a pitchfork and with several firemen prods a costumed devil off the variety show stage. Front page news of that issue of the Tri-City Herald is the tragedy of four children, between the ages of fourteen months and five, having burned to death in a house fire in Colville, Washington, two children escaping to safety by themselves, and two others rescued by the fourteen-year-old babysitter who had been severely burned. The cause of the fire was unknown. The babysitter, hospitalized, too weakened to undergo further questioning yet, had said she heard an explosion. Lest we forget the United States was then engaged in another war, at the bottom of the front page was the news that American casualties in Korea stood at 26,084, including 4036 dead. 1950 being the year McCarthy and the Red Scare grabbed national headline attention, next the Korean casualties is an article by David Baxter informing Americans on how Communism attempts to recruit the impoverished working class and middle class through parent associations and their struggles for medical and dental care, relief for needy children, and the fight against fascism, so be forewarned. The Colville babysitter would later be described as rescuing four children rather than two, and honored with a trust fund for her welfare and education, she had entered the burning house three times in her rescue attempts, and been forced to leap from a second story window on her third trip, not only sustaining burns but her shoulder broken by the fall.

Two - 22

While we’re on the subject of stuff burning down, what Fire Prevention Week is worth its salt without a big blaze presented as entertainment. The newspaper reported that on Friday night there would be a “spectacular fire demonstration”, a promise given of “flames and smoke” that would roar in the vacant lot across Lee Boulevard from Riverside Park, where Richland’s firemen would demonstrate their ability to put out a big fire quickly and safely. General Electric was at that time in charge of Richland’s fire department, so we can look upon the blaze as a theatrical staged by General Electric at the behest of the Atomic Energy Commission. General Electric, for the Atomic Energy Commission, also was responsible for the Richland Police Department. The Hanford Works Monthly Report for June 1950 informed that seventy-three persons were assisted by the police, twenty-five doors and windows were found open, there were two lost children, six ambulance runs, zero lost dogs reported, three complaints about dogs, cats or loose stock, one person was injured by a dog, there were four bank escorts, seven fires investigated, five miscellaneous police escorts, and two complaints investigated. There were zero murders, rapes, robberies and aggravated assaults, four burglaries, six cases of larceny over $50, twenty-three cases of larceny under $50, nineteen bicycle thefts, three auto thefts, one case of “other” assaults, two cases of forgery and counterfeit, eleven “Offenses Ag Fam. & Child.” (i.e. domestic violence), zero offenses concerning drug and alcohol laws, nine cases of drunkenness, ten cases of disorderly conduct, zero cases of vagrancy or gambling, one case of driving while intoxicated, thirteen speeders, six cases of running a stop sign, two reckless driving, eleven negligent driving, one case of driving defective equipment, twenty-four parking offenses and twenty-two other traffic violations, eleven cases of public nuisance, twenty-three prowlers, seven cases of destruction of personal property, eleven cases of malicious mischief, thirteen of vandalism, twelve of dog nuisance, seven of “suspicion”. There were nine missing persons, four lost persons, seven lost animals, eight lost property cases, five found persons, five found animals, twenty-three cases of found property, three cases of persons injured in a traffic accident, thirteen of property damage in a traffic accident, one firearm accident, seven dog bites, and one “mental case”.

The Hanford Works Monthly Report kept track of everything you couldn’t possibly begin to imagine. Jumping around the 385 page January 1951 report summary, I see that the distribution of the Hanford Works NEWS through local barber and beauty shops had been arranged. Something called the HOBSO had been discussed with Kiwanis, Rotary and Lions Presidents to get them interested in jointly presenting the program on the community level, and talks held with a high school principle. The Chamber of Commerce annual banquet was promoted. A report of the Ministers-Educators-Management Meeting was made to Hanford and sent also to New York. The North Richland Chaplain had booked the Atomic Energy Commission film, Bikini Survey, for troop showings (which would be about Bikini Atoll). Two-color art was completed for the hospital patient’s booklet Let’s Get Acquainted. The publication, Our Relations at Hanford Works, was revamped. There had been a lack of nurses at Kadlec hospital in January that resulted in potentially poor relations with the public,

Two - 23

and Hanford’s Special Programs’, for Kadlec Hospital public relations, was engaged in the resolution for new hires and to have several nurses in process at all times so to take care of normal hospital turnover. There were 5710 house leases processed including 78 new leases. There are construction reports, including a private construction progress report for all buildings in Richland. A list of all commercial leases made. Work orders concerning housing were listed, such as replacement of hot water tanks, the number of bathtubs installed, trash and weed removal from the city after windstorms. A condensate tank was installed at Thrifty Drug. Stainless steel soap dishes were installed over the laundry tubs in the women’s dormitories. Matrons were required to give an unusual amount of attention and care to twelve residents of the women’s dormitories who were ill in January. Three dormitory residents died during the month and their personal effects were packed and stored or shipped as required (three dormitory residents dying sounds concerning). 122 pieces of furniture were exchanged during the month between dormitories and warehouses. 7261 dormitory sheets were washed, 3874 pillow cases, 236 spreads, 35 pads and 201 shower curtains. 500 light bulbs were replaced. A spectrochemical analysis was made at 300 Area, Building 3706, relative “to larcenie that were committed in the Trailer Camp bath houses”. C. R. Brewer entertained the Columbia High School Photo Club with a lecture on Flash Photography. B. Widenbaum delivered his “Removal of Radioactive Articulate Matter from Air Streams” to the North California Section of AIChE (American Institute of Chemical Engineers) in San Francisco.

Richland was a place operated for the Atomic Energy Commission by the General Electric Company, and everything that happened in Richland, if it involved the authorities, possibly even if it didn’t involve the authorities, was going to come to the attention of General Electric, operating for the Atomic Energy Commission, which was nearly everyone’s boss. In the 1950 census, if you lived in Richland and worked for Hanford you had this noted next to your declaration of employment. For instance, a fireman was given as working for General Electric, “H”, while his wife was simply a teacher. A “patrolman” was given as working for General Electric, “H”. I am going through page after page of the Richland census in which nearly every male head of household was employed at Hanford Works.

The Hanford Works Monthly Report for September 1950 reported, “At the invitation of the Chamber of Commerce Fire Prevention Week Committee, the Community Relations Supervisor attended an evening meeting of the group and accepted a position on its publicity committee.” And, under The Public Safety Division, “The final Fire Prevention Committee plans have been formulated and a complete outline prepared. The Fire Prevention Committee is made of a group of men from the Richland Safety Council, headed by D. F. McGuire. Coordinators of the program are Bert L. Sellin, P. O. Crowder, and W. Haltoman. The outline is inclusive of the entire week starting October the eighth through the fourteenth. Bill Boards declaring the above date as Fire Prevention Week have been posted. The publicity committee has definite material ready for release. Practically all portions of the program have been

Two - 24

approved. The school program, approved in its entirety, is underway. The Employee and Community Relations Division have given full cooperation to the program and are doing extensive work.” Checking the census, I find McGuire was in the private sector, owning his own shoe repair shop. Indeed, all of the men listed above were in the private sector, not employed by Hanford, and while the Community Relations Supervisor was also in the private sector, there was another more clarifying statement made that month under Program Development concerning several programs that had required “careful planning and utilization of all the services that Public Functions comprises, in addition to considerable time and effort spent by other groups of this division to successfully launch these worthwhile projects”. Under Employee and Community Relations Divisions it was reported, “Fire Prevention Week in Richland will unleash one of the most ambitious community programs ever undertaken in this area, and more especially the most complete ever sponsored by the Richland Safety Council. The Supervisor of Public Functions was selected by the latter group to develop and prepare a program of week-long events both for Richland and Hanford Works. Considerable time and effort was consumed in planning the entire schedule, conducting meetings, developing a theme radio guessing contest, recorded radio quiz shows at schools, organizations and clubs, publicity and photography, parade arrangements and general coordination of all activities.” This Supervisor of Public Functions, who developed and prepared the programs for Fire Prevention Week, was Hanford. Among other things, Public Functions developed the Hanford Works NEWS column, and The Lady from Safetyland was produced by Public Functions for the Community Safety Division. Public Functions had also produced for the Richland Health Council a “Hi, Neighbor!” mental health series program.