ONE

We may as well start with Lawrence, the first city in Kansas, which was founded in 1854 by the New England Emigrant Aid Company, which I’m sure is an immediate attention grabber

1

This will take some explaining. You may not be up to it, and that’s fine.

2

For several years I have wondered how to begin and eventually the cat volunteered itself. I’d prefer to not begin with the cat as that immediately risks sentimentalism, but I’m often moving in the realm of minor details rather than grand sweeping existential vistas, anchoring to minutiae with the building of a world, and, besides, many people like cats. Natsume Soseki wrote a comic short story from the perspective of a cat as a means to examine Japanese society, titled it, I Am a Cat, and it was so popular it became a novel by way of serialization of additional chapters, but I understand it is often required reading for Japanese school children which suggests to me the cat has led to infantilization of the work.

Don't ask me how I remember the cat. I was about a year old so I shouldn't remember the cat. Perhaps I don’t, perhaps I only believe that I do. But we had a cat in Lawrence, Kansas, and when we left Kansas and moved across country to the plutonium breeding reactors of the Hanford Nuclear Reservation, the cat was left behind. It was a large, light-colored ginger tabby, more yellow than orange, probably more cream than yellow. Several approximately 2 and 1/4 by 4 and 1/4 inch photos of the then popular Kodak variety exist of the cat courtesy of the 1888 trademark that documented twentieth century American life by means of a click of a camera’s shutter, the light of the moment exposed to silver halides that initiated their conversion to metallic silver and the formation of a latent image, the ephemerality of days that would “never come again” preserved. A great ad campaign, the power now in the hands of the general public to preserve the present for posterity, to guard against loss, and a nudge to believe that every moment was special and unique. The film developed and printed, we can see my mother is dressed for winter in a hooded duffle coat with toggle buttons, a wool jacket that became, at least for the child-me, my foundational idea of what a coat-jacket should be like, in particular the detail of the oblong wood buttons that were sculpted to terrace-taper down at each blunt end. A traditional duffle has buffalo horn toggles, but I remember from when I was a little older (which is how I know the coat was red) the visual and textural interest of the wood grain of those buttons, which I guess means her duffle wasn’t traditional. The

One - 2

hood up over her fashionably short black hair (refer to the mid-1950s style of pixie cut popularized by film stars Audrey Hepburn and Shirley MacLaine), wearing dark denim jeans with rolled cuffs and two-toned saddle shoes, in three of the black-and-white images she holds an about six-month-old me also bundled for winter in a pillowy hooded white onesie with attached feet and mittens. She appears to struggle with the winterized bulk of her child, and I look uncertain, upper body and arms leaning away from her rather than, as a primate Homo sapiens sapiens, instinctively seeking to cling to my mother. In three other photos I am no longer on display and she is instead with the cat that is collared and appears to even have a short leash attached, a slender cord with a handle loop, which means the cat was treated as a house cat, unusual for a time when cats were usually thought of as needing freedom to roam outdoors. Several inches of uneven snow mottle the ground before the dry sidewalk on which she stands in front of the apartment building in which we live. In one image she holds the cat as she had held me, in her left arm, though securely, so by comparison it's easy to see the cat was nearly as large as me but not so cumbersome and unwieldy a fit.

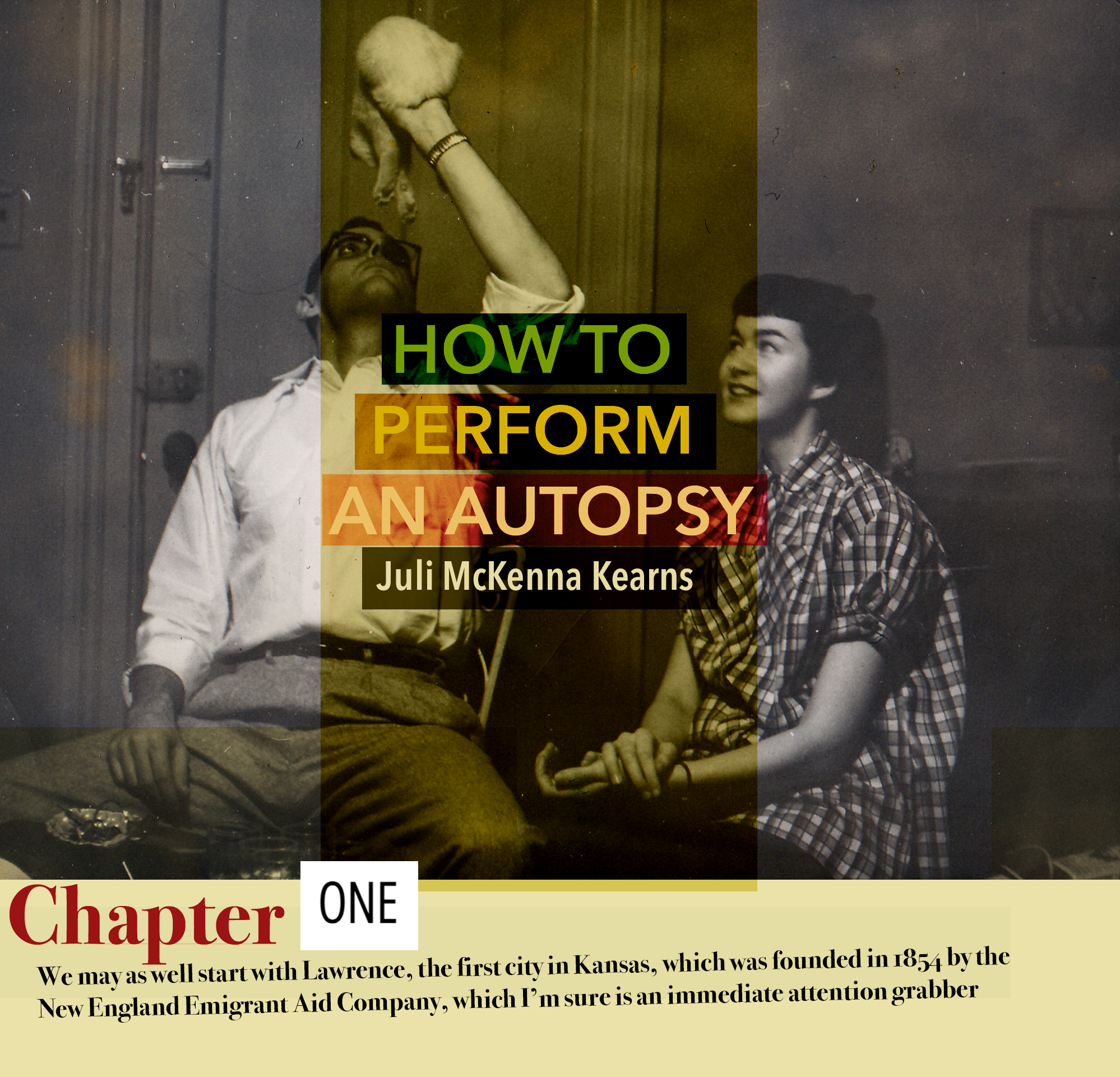

Give or take about nine months before this, in another photo from when my mother was pregnant with me, her black, coarse hair long and in a high ponytail with a bow, short fringe of bangs over her forehead (she always wore bangs), dressed in a plaid maternity blouse, short puffy sleeves, buttoned up to the collar, she sits beside my father who holds the cat in one hand raised up above his head, expressionless gazing up into its face, the cat then much smaller, a large kitten. The 4 inch by 3 inch night scene, in the room of an unknown older apartment, has been caught by a professional grade camera, and would have been hand printed, likely by novice, it shows the unmistakable splotches that may occur with time when a print’s not been properly fixed and washed. The light from an unseen ceiling lamp sets the moment in a way forgotten by color photography and never quite captured by lo-fi black-and-white Instamatics, the grays unsettled as in noir dim early Alfred Hitchcock while the white of my father's casual dress shirt is sharply highlighted. As he leans back in a metal garden chair to stare with vacant but cool intensity up at the cat, his eyes held upon the cat’s in what seems a challenge and an imprinting of his dominance over it, my mother too gazes up at the cat but she passively smiles, her cheeks brightened by the illumination of the unseen ceiling lamp directly above them, a light that quickly drops off so the room beyond fades away in shadows. The light catches the brass of an ashtray on the low table before which they sit, but so feebly brushes the rims of the seven glasses resting also on the table that they are only vaguely glimpsed at the very bottom of the photo. I can now smell the beer and realize, finally noticing the glasses, that more people were there than my parents, my fetus self, and the photographer, that this is instead the scene of a party. In the background is the apartment’s front door, which has a deadbolt and a chain that is off the hook. A small alarm clock on a bureau next the front door reads 7:26. It is early evening and they're at a gathering in this apartment because there is no drinking at the Rock Chalk Cafe or any other establishment in Lawrence because the “open saloon” is still prohibited in Kansas, a state that was dry until 1949. In the photos the cat appears so light as to be almost white rather than ginger, but it’s not from these photos that I recollect the cat.

One - 3

And when I remember the cat I don't so much as remember it as how it died.

My father is twenty-three, my mother is twenty-four, they are not quite youths but they are young in these photos, these people with whom I lived for seventeen years. Their public face was always so guarded, posed, not poised, any hint of the impetuousness of youth is already absent. Their interior lives actively recede from the camera.

My mother said they lived in two apartments in Lawrence after they were married, and perhaps this older place is their first apartment and not that of another individual. Of the few furnishings and knick-knacks captured in the photo, there is nothing familiar in the room, but there is the cat. My impression has always been that this is not their apartment as their aspects seem to be those of visiting partiers rather than the ones giving a party, but then if this wasn’t their apartment then their cat wouldn’t be there. Though, for all I know, it wasn’t yet their cat, it could have been their prospective cat, perhaps this picture was taken because it was their very new cat that had been in the care of the person to whom the apartment belonged. I don’t know. My father's face upraised in the image in which he gazes up at the cat, he appears to have a hint of a mustache, which has only been captured in one other photo, what seems an impromptu experiment at a portrait, also hand printed, from the same time period, perhaps also taken by the forever anonymous photographer who captured the image of him with the cat, but his hair is slightly disheveled in the solo portrait and he wears a jacket or heavy shirt so it was likely shot on another day. In the solo portrait photo his glasses are removed, and he has the same cool stare, looking beyond and to the screen-right of the camera. Dramatically lit from above, the screen-left half of his face is almost entirely obscured by shadow while a half-circle of glare cuts across the portrait forcing his screen-left right eye out of the dark with an effect of near pseudo solarization. The focus is only on him, the background blurred so there is no hint at the environment, but the way the light falls from above it could be the same room, the same ceiling lamp as in the beer party scene. The negative had been poorly processed and dried so that white splotch marks horizontally streak part of the print. When a young teen and I first noticed the photo in the family photo box, I asked my mother who it was. Though I thought it resembled my father, the same dark hair and complexion, the same full lips and dimple in his chin, I was thrown by the mustache and the chiaroscuro lighting, how cinematographic it was. My father seemed to be wearing the personality of a different person, one who hadn’t completely settled into being the scientist with black-rimmed glasses and wife and family. Almost bohemian. A trial identity adopted when one is contemplating shedding the person in one’s driver’s license. My mother glanced at the photo and said she didn't know who it was, then corrected and said it was perhaps someone she'd dated but she'd forgotten their name, it may have been John, but she couldn't really place the face and she wasn’t certain about the name. As she didn't associate the portrait with my father, I noted it as "John" with a question mark. It was only a few years ago that, examining the photo again, I realized it was unmistakably my father.

I never knew the story of how they came by the cat. I once asked my mother about

One - 4

the cat when I was a preteen, to confirm what I remembered having been told about the cat’s death as a child. If we’d ever looked at the photos together I might have thought to ask its name. Do other families look at old photos together? I don’t know. She only spoke of the cat as “the cat” and never said its name. She may not have remembered it.

Neither of my parents had any interest in photos, so images were rarely added to the family photo box. Their disinterest went beyond not having the easy access of at-one's-fingertips digital photography until late in life. My mother protested the few times I wanted to look at the photos, resistant to taking down the box from the upper shelf in their bedroom clothes closet, and when she did relent she would leave me alone with them behind the closed door of their bedroom, never remaining to discuss them, the places, the times, or who were the people in the images from her youth. My father never handled the dark gray box—about nineteen inches long by fourteen inches wide, about five inches deep, about the size of a bakery box for a half-sheet cake, with an attached folded lid—or looked at any of the photos contained, reminiscing. I never asked him to get down the box because it wouldn't have occurred to me to ask him. I would say there was probably no reason for my mother to be reluctant to pull out the box other than not wanting to be bothered, but that would be the lazy way out. In families that are troubled, all photos, no matter how banal, are potential silent witnesses of one lie or another that great pains have been taken to hide. In our family, not a single photo was ever framed and put on a shelf or hung on a wall, not even carried in a wallet. Indeed, when I was small, I chanced to see in my father’s billfold a lone photo portrait of a woman and wondered who it was, if it was an old girlfriend why would he still carry her photo, then when I was a little older discovered it was of the type that came with a billfold when purchased. The only portraits placed on display were of an elder white-bearded Brahms, the nineteenth-century German composer with whom my mother believed she had a beyond-the-confines-of-time spiritual relationship, and the occasional television father figure actor my mother would become too intently fixated upon in what I, even as a child, understood as her quest for a replacement father.

My father’s parents didn’t display photos. My mother’s parents didn’t display photos.

I don't display family photos either, and for various reasons I tend not to shoot photos of family. As an individual who has taken and discarded tens of thousands of photos, I deliberate for too long on this subject at this point, on what to say, considering how I should approach what is complex not only emotionally and personally, but also artistically, philosophically. The adage that a picture is worth a thousand words is not necessarily untrue but forgets the problem of viewer misinterpretation even when photos aren’t removed from historical or intimate context, and whether or not the picture itself can be relied upon, the intention of the photographer, whose story or perspective is being framed within the camera. As Homo sapiens sapiens are one large family, in the same way that photos of troubled families are potential silent witnesses of one lie or another that great pains have been taken to hide, so too is any photo a potential record of uncomfortable truths and disfigured realities. On the other hand, art can magically transcend, transform, reveal. But words are still often needed to inform and abet comprehension.

One - 5

Returning to the photos of the cat in the snow, they would have been likely courtesy of 616 film, 6.5 x 11 cm format, which was perhaps used in a Kodak Target Six-16, an amateur’s box camera dedicated to panoramic shots, viewfinders on top and side for portrait or landscape view. The type of film was probably Verichrome Pan, which was especially good for box and medium-range cameras, a general purpose film that the amateur could rely upon with its wide-exposure latitude. Or the camera may have been used in the Kodak Vigilant or Kodak Monitor, which were also 616 but had a fold-out bellows and were better-crafted and far more costly. This information may not seem of any significance, but it is to me else I’d not have researched it. These are people I don’t really know and whose history is all question marks. I’m considering the personality of the user and their pocket book, though neither may come into play if the camera was perhaps a gift or passed along when the former user acquired another camera they preferred. The clunkier, more finicky, and not-so-svelte box was sold originally for four dollars while the Kodak Vigilant sold for about forty-two dollars and the Monitor for about forty-eight dollars, the last of the Kodak 616 models, discontinued between 1948 and 1951. That’s a big price bump, and that the camera was being used in 1958 by a newly married couple who weren’t photo bugs means they didn’t purchase it, instead it may have been a hand-me-down or a pricey high school graduation gift to my father, though the lowly box camera could have been acquired as a hand-me-down, or was a personal purchase or gift when a teen.

If, in the photo of my mother holding me, I appeared to be pulling away from her as though I'd prefer to fall back into the void rather than be embraced by her, that's not speculation, that's how things were. I had trust issues with my parents. But I also remember the fear of falling back, of being carried with an arm braced under one's bottom but no support around the back, being swung around roughly (my chest reflexively tightens with an unvoiced gasp, it’s uncomfortable to imagine), the surprise and alarm of one's head snapping back and the wild reaching to attempt to grab hold of the cloth of a sleeve and hang on. When I was a child and I first saw those photos of the three of us—my mother, me, the cat—I experienced the surprise of an ancient jealousy unearthed as I looked at my mother cradling the cat in her arm. As if I could easily be replaced. The associated pain startled me and I only now realize that emotion was the mind of the infant-me. My father doesn't appear in these photos and I assume, perhaps erroneously, he was the one who took them. As I’m closely examining the photos, the question then occurs to me, where was I when he was photographing my mother with the cat? Who would have been holding me? As a child, looking at the photos, I'd the feeling of not just being out of sight when replaced by the cat but disappearing. The photos weren't processed for months, not until the following summer when we'd already relocated from Kansas to Washington State. When photos are conveniently printed with a date, I find my parents would often wait half a year to process a roll of photos, which can make narrowing the time frame to an exact month sometimes impossible, and if the photos haven’t been printed with a date there’s a ninety-nine point nine percent chance that no one has noted date or description on the rear. If the contents of that box ever turn up in a flea market, there is little chance the people represented therein will ever be identifiable. Hundreds of thousands of such anonymous photos have landed in thrift shops or in flea markets by way of estate sales because they ceased to have a context that made them matter.

One - 6

They are now curiosities. Who was this person pictured and what made that moment significant enough to be captured. What was the image intended to represent for either the photographer or the individual in the photo? When a photo of anonymous individuals is scrutinized, whole lives are reconstructed based on a hairstyle, an article of clothing, a facial expression. “Look at that scowl, they obviously don’t like standing next to that person.” “The halcyon days of youth, how happy and carefree they are.” Conjectures made with too much confidence. One of several apparently happy college girls seated on a grass lawn before their sorority house may miserably be covering up traumatic secrets she feels she dare not speak about. A person who appears angry may be discomfited by a headache or upset stomach or an article of clothing that is uncomfortable. The identification of a woman as one’s great-grandmother in the family photo record doesn’t make her so if the claim is erroneous.

To check myself, the sense of my pulling back into the void, I examine the photos again to make sure I'm getting this right, and realize the story I've just told isn't apparent, if another person were to glance through them they would only see a woman struggling a little to handle the awkward bulk of an infant snugly attired to stave off the midwestern cold and that the child’s ability to cling to the parent is hampered by the bulk of their onesie and mittens. When I revisit the photos with the intention of being as objective as possible, even I don't see anything more than that. Yet my initial immediate physical sensation upon seeing them is the fear of an unreliable embrace and the avoidance impulse that comes of learned distrust.

Almost always, there are at least two stories.

What to make of my mother not recognizing her husband in a photo? I don't believe she did recognize him, though it's possible she did. Her world was an odd one, not connected with reality, most often by choice. Or I should say that she and my father fabricated numerous false worlds they called reality. They lied as a matter of habit, with almost every breath, and also practiced gaslighting, which the American Psychological Association defines as “to manipulate another person into doubting their perceptions, experiences or understanding of events. The term once referred to manipulation so extreme as to induce mental illness or to justify commitment of the gaslighted person to a psychiatric institution but is now used more generally.” The term has its origin in George Cukor's 1944 film Gaslight, in which Charles Boyer attempted to convince Ingrid Bergman she was insane by having her believe she imagined the sound of footsteps in the attic at night, they were all in her mind, and he had her believe she was responsible for objects disappearing, such as a painting that repeatedly absented the wall, she was the one compulsively, insensibly removing and hiding it and was bewildered by its absence because she was unstable and forgetting her actions. Charles Boyer was at least after something sensible in his gaslighting of Ingrid, he was spending his nights up in the attic searching for precious jewels that had belonged to her dead aunt, who he’d murdered. His goal was theft. For a long time, not having seen the film since I was in my teens or early twenties, I misremembered it as being directed by Alfred Hitchcock, and for good reason, Gaslight was based on a 1938 play by Patrick Hamilton who in 1929 also wrote the play Rope, which served as a base for Hitchcock’s 1948 film of the same name. Ingrid

One - 7

Bergman’s turn in Gaslight was immediately followed in 1945 by her starring in her first Hitchcock film, Spellbound, in which a man struggles with phobias and dreams that with some detective-psychoanalysis turn out to be symbolically-expressed traumas he has experienced and forgotten. In Gaslight, Ingrid Bergman’s character has been convinced she is mentally unbalanced, but is proven not to be by Joseph Cotten, while in Spellbound Ingrid Bergman plays the psychoanalyst who helps Gregory Peck recover lost memories, proving he is not insane.

My parents’ lives were so much lying and gaslighting that it's often impossible to recover the truth from the false histories they created. When I was a young child, they lied. The gaslighting began in earnest when I was a preteen, but the groundwork of lies was also destabilizing.

Google Maps. 1316 Massachusetts Street, Lawrence, Kansas. Other than the biology of human reproduction that eventually evolved in consequence of the ever mysterious conception of the universe in which we precariously reside, I don’t know what I’m doing here, but worlds of a lot happened before I was born in a Kansas that already liked to think of itself as “It’s always been this god-ordained way” though it had only been a star on the flag of the United States of America for ninety-six years, which may sound like a lot of time, and it may be for a gnat, but there were then some still alive who had been born in the year of its transition from far west territory to statehood. The place where we lived my first year still stands and is easily recognizable though much has changed about it. I know we lived at this address through the agreement of a census and Google Maps with photos. A six-unit rectangle of an apartment building of two floors, oriented so the width-narrow side of the box is the facade that addresses the street, it’s configured like a motel with exterior front and rear entrances/exits to every apartment on the long sides. I have always imagined the wood siding and shingles of the original facade stained a redwood color to coordinate with a low-slung style of quasi-Frank Lloyd Wrightian architecture, intended to blend with the landscape, downgraded and redefined to communicate the unimposing aesthetic of a sleek urban cabin. The then new building likely having replaced a home such as the standard early twentieth century two- and three-story single family residences neighboring, or maybe a lingering Victorian structure, stood out as at least novel to the area pictured, as if it perhaps would prefer to be a state over in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado, but no doubt it was fashioned to appeal to young student couples graduating from the dorm to a one bedroom apartment. At some point between then and now that low-profile design must have made for problems because the roof was raised, a vented attic was constructed above the second floor, and the addition of an obtrusive enclosed gable swept away the modernist cabin-like sensibility of the facade facing the street. The minimalist windows, longer horizontally than vertically, each composed of two glass panels set side-by-side, are a contemporary rather than traditional profile for the 1950s. The original wood balcony of the second floor, the baluster of which angled out away from the building and invited one to lean against it, forearms resting on the wide cap rail, a rather romantic yet rugged detail, probably rotted and was thus replaced with the current wrought iron that seems pedestrian in comparison. The landscaping and concrete walks, once

One - 8

crisp and defined, are now uncertain as to where what begins and ends. The demarcation line announcing a street is exhausted and no longer cares.

In 1957 Dwight D. Eisenhower is president and his vice president is Richard Milhous Nixon, whose own presidency will end with the Watergate scandal and his resignation in 1974. In June of 1957, sandwiched between twenty-two-year-old Elvis Presley's "All Shook Up", "(Let Me Be Your) Teddy Bear”, and "Loving You" hits in July, the most popular song crooned over the radio was a twenty-three-year-old Pat Boone’s lamentation about writing love letters in the sand and how his girl laughed when he cried each time he saw the tide erase their love letters, the vows they made meaning nothing to her. Bitter comfort for the heartbroken. Not the best jukebox selection for a first date.

Their parents were of what is called the Greatest Generation, if you believe in generational labeling, which is simplistic and creates assumptions that categorize with too broad a brush and give a false read on cause and effect, such as much that is credited to the Boomer Generation was actually the brain child of individuals born during the years of the Greatest Generation, or even the Lost Generation that fought in WWI. The Greatest Generation, born from 1901 to 1924, was originally the G.I. Generation, Government Issue or General Issue, a moniker suggested in the 1991 book Generations, but then news anchor and journalist, Tom Brokaw, called them the Greatest Generation and it stuck, because heroes were wanted and thus forever America would know its heroes by their birth year and that they were the generation who fought the Nazis in WWII. My parents were of the Silent Generation, which means they grew up with conservative, anti-communist, blacklisting McCarthyism, which was created in part by the Greatest Generation, to which Senator Joseph McCarthy belonged. The Silent Generation was guided and fed by the Lost and Greatest Generations. My mother’s conception of the world at large, history and current events, was near non-existent. Before going to college, she had a piano teacher who she would occasionally mention to me, who she had liked, the smartest woman she'd ever met, she said, knew all about politics and was well-versed on everything. For instance, if one was trying to converse on domestic and world affairs, no matter the topic, my mother would say, "Mrs. So-and-So-My-Piano-Teacher was the most intelligent woman I ever met, she knew everything," which was the cue that the conversation on that subject would now end, that my mother would commandeer the conversation over to a self-interest because my mother had to be the center of the world. Only because of her doing this repeatedly forever, I eventually made an effort to try to dig down and learn something about the piano teacher and her opinions, a spontaneous move on my part when it one day dawned on me that despite all these mentions I knew nothing about the teacher's beliefs and opinions that made her the smartest woman in the world forever. I asked about them. What did she believe in? My mother was caught off guard, then after some mind-searching and wavering on her part, and prying insistence on mine, she said, "McCarthy". The piano teacher had loved and worshiped McCarthy and spoke often about him. Taken aback, I asked, "Joseph McCarthy?" Yes, that was it, Joseph McCarthy, my mother was pleased I recognized the name, a great man. I asked, "Do you know who Senator

One - 9

Joseph McCarthy was?" No, my mother replied, becoming defensive. I told her a little about McCarthyism and the witch hunts of the anti-communist Red Scare, and as I spoke she hardened into a posture of not hearing, though to her credit she was not herself a hater of socialists or communists, when I was ten she told me two of her uncles on her mother’s side had been communists in their youth and how her mother was ashamed of this, and she probably had been ashamed, yet she unexpectedly, very briefly, no details offered, brought it up herself a couple of years later, treating the subject as one that gave a veneer of subversive excitement to those brothers. “I don't know anything about that," my mother said about McCarthy, and shut down the conversation. The Silent Generation is described by some as being so conformist they were silent about McCarthyism, but the eldest of them was twenty-two as McCarthyism peaked, during a time when one couldn’t vote until they were twenty-one, and the youngest was five years of age. My mother’s piano teacher would have been of the Lost Generation.

They are very young marrieds in Universityville, my father less than a year from graduating with his master’s in biophysics and having his photo taken in cap and gown in procession past KU’s towering World War II Memorial Campanile & Carillon that was dedicated in 1951. My mother, a year older, was a latecomer to school after several years working to help support her family. A freshman at twenty-one years of age in 1954, older than the others in her class, she felt out of sync. Everything I know, it's all disorganized bits, their lives a blank, especially my father's. With the exception of a couple of stories related in a clipped few sentences, my father shared no personal history. We look for the who of people in what they say, what they do, how they relate to others and the world, their interests, and when these usual avenues leave us with puzzles and questions we might look to their origins. Perhaps others had stories from him, about him, but with me, his eldest child and daughter, my father had little to say about work, he didn't talk about university, he didn't talk about high school or elementary school or any of his teachers, he didn't talk about his childhood, he didn't talk about experiences had before or after I was born, such as places he'd visited or memorable foods he'd eaten, hometowns, homes, he didn't talk about one single friend he might have had in his life, he didn't talk about his parents or other members of his family, he didn't talk about my siblings, he didn't even talk about my mother, and my mother had no stories about him to relate because my mother was only interested in her own stories, which focused primarily on hates, such as her hatred for her parents, but dry on facts except for a few that served as launching pads into her grievances, not that many of them weren’t legitimate. My father did an exceptionally good job at not talking which was perhaps a reason my mother was attracted to him, he gave her the floor unconditionally, forever and ever, without question, rarely challenging her, not so much conversing as going along with her up to the point where he sometimes wouldn't, and perhaps a reason he was attracted to her was because she wouldn't be one to pry into the who of him very much. Because of the bizarreness of their relationship, as a teenager I used to look at them and wonder what brought them together, and at the same time I was a little afraid to know, as they so ostracized their children that the idea of family was absurd window dressing, they'd no room for us in any part of what bonded them, yet they'd kept

One - 10

having us. When I was about eleven, my father and mother on their side of the breakfast bar, we children on our side, having been purposefully convened for a meeting of import to us, my mother and father holding hands, she announced that they had made the decision they would never again fly apart from one another so in the case of a plane crash they would both die together, never mind leaving behind young children, they couldn't imagine life without one another. Which I believed, because our household was sick with their weird, bizarre bonding.

How did they meet? They met because they were born. He was born and grew up in Ponca City, Oklahoma, and southwestern Missouri. She grew up circulating around Chicago but with time spent in Glen Ridge, New Jersey, Wheaton, Illinois, and Cleveland, Ohio. The prestigious Glen Ridge (high median income, long list of notable people, check Wikipedia) never was mentioned, nor was Wheaton ("One of the best places to live in Illinois..."), Cleveland Heights only once or twice and so confused issues, and the story about Chicago was they had lived in Oak Park, Frank Lloyd Wright was the architect of a number of homes in Oak Park, and she had known a couple of people who lived in Frank Lloyd Wright homes. My grandmother spoke about Oak Park as well, mainly to note that it wasn't what it used to be, i.e. she would have been referring to white flight and integration, racism hinted if not spoken outright. My mother wasn't an appreciator of architecture in any form and would have never taken an opportunity to visit any Frank Lloyd Wright home as a tourist as only my mother should ever be the center of attention. I never learned whose homes these were that had been a part of her youth, it was just a rare tidbit of information to grab onto and, already an appreciator of architecture, made me feel like I had a quasi-connection to Frank Lloyd Wright history. She was born in Chicago and her family was in Chicago when her father was released from his job as comptroller and treasurer for a large retail company, something something to do with embezzlement he supposedly didn't commit, someone else did but it was pinned on him and he was forced to take the fall or something and quit or was fired something something and that's how he ended up unemployed for something years. From census records and other documents I know her father was on the low end of the upper ten percentile of earners in 1940 when in Glen Ridge, and looking up addresses I've gathered from census records and other documents, I’ve learned just how nice were the houses in which they they lived in the kind of nice upper-middle-class neighborhoods that have always made me wonder as I passed through them, on my way from not that neighborhood to another not that neighborhood, "Where and how do all these people get their money?" After the loss of his job, my mother's father unable to find another one for I don’t know how many years, my mother put off going to college and entered the workforce, the only time she ever would do so in her life, something something in a large retail store situation. When I was a youth, during one of my afternoons babysitting her in the kitchen while she drank, she told me she had been an artist in the ad department and had quickly and capably doodled a couple illustration type line drawings of children that had a very defined, well-rehearsed style (when I look for something similar they recall the drawings of Eloise Wilkin, called “the soul of Little Golden Books”), then during our last period of contact when I asked her about this she defensively objected, no, she didn’t know where I’d gotten that idea, she had

One - 11

worked in the mail department. She was expected to hand over her paycheck to help support her parents and she complied without question, but if she was ever very curious about the facts of the matter of her father's tumble from a highly desirable position she didn't display it, perhaps because she had no interest in the lives or histories of her parents (or most anyone else for that matter). As the lives of her parents directly affected her, this void of curiosity seems insensible, but this is the way she was, perhaps because she had been raised to not question her authoritarian parents, but her resolute disinterest also enabled her in the near constant construction of fictions she handed over as facts. I do know it is true that there was something something concerning embezzlement, it was once or twice even briefly mentioned around me by my grandmother in a "Don't even think of asking a single question, besides which he was innocent" way. And maybe he was innocent. I don't know. Because they always pled hardship though they were comfortably middle class in their old age, because he was the kind of asshole grandfather who would play chess with an eager first-time ten-year-old, glory in winning and thus prove to you why you should never ask to play chess with him again as you weren't up to his level (he refused to teach me the game as I was a girl, but did teach my brother, B), and because our grandmother was a frustrated social climber who, after their fall from grace, had taken labels from their older, classier Marshall Field’s coats to sew into their cheaper coats, I was inclined to be suspect because I knew that, on the competitive level, social position and money had meant everything to them. Would our grandfather be capable of embezzlement, this man who could scarcely sputter two sentences without frothing as he was such a lethal pot of barely suppressed burning rage and spite-filled resentment over the fact the brilliance of his accountant intelligence hadn't been appropriately recognized by all, the self-professed smartest person we would ever know, corroborated by my grandmother who also held he was the most moral man in the world. Was his natural acquisitiveness capable of persuading his conservative Methodist or Presbyterian ethics (news mentions show he participated in both denominations) that he should have been making more money so why not purloin it and imagine others would be too dull-minded to ever figure it out? Or was he, a Freemason, staunchly trustworthy in all dealings and as bitter as he was because he'd been wronged, wronged, wronged, not to mention he was terminally infuriated because he was so much smarter than the rest of us and we were so beneath him that we hadn't the intelligence to recognize his genius.

My siblings and I, our worlds far apart even when young, were at least in agreement on the embezzlement story as such a foundational part of the family lore, though never discussed, though nothing was known about it, that some of us would joke the reason the mahogany Mason and Hamlin parlor grand piano occupied a hallowed central role in the family was because it must have a hollowed pirate's leg in which the embezzled monies were hidden and they were still waiting the day they felt free to spend it. Almost always there are at least two stories.

We are all part fact and part fiction.

How much room is there in the world for concert pianists? When my mother lands at the University of Kansas, studying music because she's going to be a concert pianist,

One - 12

I know from a lone postcard that her parents are then living in Oak Park where their downsized lodgings would have been overwhelmed by the Mason and Hamlin on which my mother has practiced her Bach and Beethoven and Brahms for a good part of her life. This address, in the shape of an “Oh woe is me look what I’m reduced to” apartment building on North Austin Boulevard, on the very border of Oak Park, literally a couple of footsteps west of the Austin neighborhood, however nice, might be the best evidence that my mother's father had not been an embezzler. Or maybe he hadn't embezzled enough. Grandpappa (my mother's mother dictated we should call them grandmamma and grandpappa), I'm sorry if you're innocent, and I'm slandering you, however long after your death, but maybe you shouldn't have exploded on me and gone so red in the face I thought you were going to stroke out when I casually remarked that the American railway system was dying, and if memory serves I qualified that as per passenger travel. It doesn't help matters that the conversation in question was one of the few I recollect, for I only met you perhaps eight times total, and you made it more than abundantly clear that as I was female I was unworthy of ever participating in any discussion with you. Or maybe you just didn’t like me.

Home Owners’ Loan Corporation maps made about 1940 rated the borderline Oak Park area in which they were living in 1954 a downwardly trending "C", largely inhabited by white collar clerks and in decline due to "Jewish infiltration", while across the street from them the area was considered no longer lucrative due to "Italian infiltration". They had moved from a Cleveland Heights address that in 1940 had been rated as a good investment "B", populated by professional executives, junior executives, and business owners, with "some families of German, Italian, Jewish descent", also having lived in a “B” neighborhood in 1940 Glen Ridge, right across the street from the “A” class executive homes that looked exactly the same as the across the street “B” league homes but weren’t. Even with their downward mobility in status, they managed to send all three daughters to university. I could be wrong, but I trust this was because of my mother’s mother, who had been to college, as had most of her relations. She came from a family of higher education. My grandfather didn't.

My mother had attended Cleveland Heights High School. Beside her senior year photo are the clubs in which she was a member: Red Cross, Hermes (a Latin club), the Music Appreciation Club (listened to music), the Science Club, the Friendship Club. She does not appear in any photos of the members of these clubs, nor is she listed as a member who doesn’t appear in the photo. The science and latin surprise me as she had no interest in either. She never spoke of any of these clubs but then her experiences may not have been memorable or she may not have participated. Cleveland Heights had a strong, nationally recognized music department, yet she didn’t participate in the renowned choir.

The way my mother compressed her KU story I always thought she'd been there for a year when she met my father and married but I find her in a 1954 KU yearbook in a group of twenty-nine young women designated as North College I. She is third row up, third from the right. About half are dressed in light-colored sweaters, the other half in light-colored blouses, and with the exception of two who have slightly longer

One - 13

hair, it is obvious that gently curled short hair that ends a little below ear length is what they were doing in Kansas. My mother stands out because her hair is jet black and is unfailingly always the darkest, and her face shape is round. She has so unique an appearance it would be near impossible to confuse her ever with another, even standing out in her own family though she and her two siblings bear a marked resemblance to one another and their parents. She is attired in a dark short-sleeved jumper dress with a fitted waist over a blouse with a high frilled neck. To her immediate left is one of the two lone girls in the photo who have hair all the way down to their shoulders. That girl merits a mention for, though she is dressed in the conventional short-sleeved white blouse, she has differentiated herself with a beaded necklace from which hangs an unusual and dramatic palm-sized large pendant that stirs one's curiosity to want to view it more closely so one might see what it depicts, which is impossible to do with her forever in miniature. My mother's attire rouses my curiosity as well for she wears this jumper or another in a couple of other photos from earlier years, paired with different blouses, always a slim dark bow of likely velvet ribbon knotted at her neck, but in this sitting she appears to have left the usual dark neck bow untied, which is surprising as she is typically fastidious in these early presentations of self. The jumper dress is similar to one worn in the 1959 film The Wasp Woman by the female owner of a cosmetics company who takes a rejuvenating wasp royal jelly that turns her into a half-wasp, half-human killer. The dress in the film has a boat neck rather than rounded and is a sheath in shape while it may be my mother’s has a full skirt, I can’t say for certain as it’s hidden in the photo of her with her dorm mates. If the one she wears in 1954 is the same as in a 1951 photo then it would have a full skirt, but she wasn’t inclined to wear clothing for more than a year or two so the jumper dress she wears in 1954 may be a different one. In the poster for the film the woman is a giant wasp with a beautiful human face and is clasping the body of a man who is the size of a child in comparison, and as he is in white pants but shirtless the impression given is similar to an infant in a white swaddling blanket. In the movie, when she transforms she instead has the body of a human and the fuzzy face and antennae of what we are to believe is a wasp. She morphs back and forth in a Doctor Jekyll and Mr. Hyde manner, and rather than stinging her victims she drinks their blood, vampire-like.

As for North College, the name is a reminder of a building that no longer existed. North College was the first construction of KU, established in 1866, a lone structure perched atop the hill of Mount Oread, past which the wagons of the Oregon Trail had heavily trundled west, and upon which was a free state fort during the Bleeding Kansas days. Only fifteen years later, the North College building became an asylum for "feeble-minded" children throughout the 1880s, then with renovations was transformed into KU's law school for three years, but the law school must have decided the old building wasn't up to par as it then became the fine arts school, in which the music department was folded, finally to be condemned in 1917 and dismantled. So in the 1950s what is termed North College seems to refer to fine arts students who study at Strong Hall, the main administration building, where the fine arts school was then housed, the music department in the basement and first floor. KU's School of Music gained a dedicated home in the brand new Fine Arts Murphy

One - 14

Hall that was built in 1957, but by then my mother had dropped out. There are four groups of North College freshmen women pictured in the 1954 yearbook, and if I search out the page on that part of KU trusted to prepare them for a future in the arts I find, "Every day 490 students laden with music books, paint brushes, portfolios, and similar paraphernalia enter Strong Hall for classes in the School of Fine Arts. This school of the University, one of the finest in the Midwest, offers unlimited opportunities for art and music enthusiasts. Dean Thomas Gorton leads a staff of 56 instructors." Nine new teachers had been added that year. When I look up Thomas Gorton I find that he refused to allow jazz to even be played in the practice rooms at KU.

What was my mother, who lived in Chicago, doing at the University of Kansas? Was it as fine a school for the Fine Arts as stated? An attractive school for an individual supposedly preparing for a career as a concert pianist? The hometowns of the freshman students are listed next to them in the yearbook, and the vast majority are from Kansas, with a few from Missouri, often Kansas City, Missouri, which makes sense, Lawrence being so close to Kansas City, and many who live in Missouri will be connected with Kansas through relations who live there. Another yearbook reveals that the girls identified as North College I live on the first floor of their dorm building, North College II on the second floor, etcetera. Only one other student in the four North College groups is from Illinois, also in North College I. In the mid-1950s, the University of Kansas seems more a home state school rather than one that has a national appeal.

Individuals who are estranged from their families may be left without childhood photos. I was first estranged from my family when I was seventeen and experienced this. I'd the memory of childhood photos, and especially with the photos in which one appears they can feel like dislocated pieces of ourselves if one is deprived of them. When my family and I reconnected for a time, I went through the family photo box and, without telling anyone, took the few photos of which there existed copies, which weren't many but I at least had these when we were later estranged for two decades. Why would I not ask for the copies? Because to ask would have resulted in being given an excuse for why I couldn't have them, and to even be viewed with suspicion for having asked for them. If you expressed an interest in anything, you were viewed with suspicion, like they were wondering what you were looking for, what bad thing were you hunting. Then during our last period of connection, I volunteered to scan and digitally archive the family photos that a sibling had been given by our parents, which comprised the majority of what I had known to exist. Among them were several I reasoned were likely 1950s views of buildings at KU. I find one of the unidentified photos is of Strong Hall. A sister of my mother's is in the 1954 yearbook, the one closest to my mother’s age, and is identified as living at Locksley Hall. This sister never once entered my mother's few and spare stories of KU, but I discovered another one of the unidentified photos is of the long-since demolished Locksley Hall. Some other photos, obviously from the same camera and taken by the same hand, were of the visit of Queen Elizabeth II to Chicago, in July of 1959, on the Royal Yacht "HMY Britannia". My mother never took photos, and if she had she would never have thought to make notes on the back identifying any of them. The photos are different

One - 15

from those taken by a typical family photographer as they don't show any people, only buildings considered memorable and events on Lake Michigan connected with the formal opening of the New Saint Lawrence Seaway by Queen Elizabeth II and President Dwight D. Eisenhower, held in conjunction with the 1959 Chicago International Fair and Exposition. Whoever took them had a surprising, fledgling eye for photography, giving attention to framing, and would have either been my mother's mother or the sister who had been at Locksley Hall. A photo of my Locksley Hall aunt shows her with a twin reflex camera hung on a strap around her neck, which I assume means she was interested in photography. She would marry an individual who graduated from Northwestern University but he was born in Lawrence and after marrying in Seattle, Washington they would make their home in Lawrence for most of their married lives.

An uncle of theirs, brother of their mother, had a "farm" on Route 2 somewhere around Lawrence and the Palmyra-Baldwin area to the south of it, farm placed in quotes because I don't know what that means as he spent his time traveling the world as a coordinator for the Department of Interior Office of Petroleum, when he wasn't an employee of Standard Oil, also a research engineer at KU according to his obituary. I've wondered if a reason my mother and her sister landed at KU was because they had an uncle located there, though their eldest sister had gone to school in Arizona, probably to escape the reach of her parents for a year or two. My mother never discussed why she'd gone to KU or if she'd applied to any other schools, and as a child I didn't think to question her having been at KU as it seemed to me the kind of "fact" that was mandated by fate.

My mother appears in the 1956 yearbook living in Grace Pearson Hall, one of forty-seven women pictured, she's in the second row, fifth from the left. Nearly everyone wears a short-sleeved sweater with a very short necklace of beads, some in pearls, most of the women in light-colored sweaters and dark skirts. My mother's sweater is darker, appearing gray in the photo, her skirt full and a slightly darker gray. She distinguishes herself by being the only one to wear a fashionable belt, likely black, cinched around her waist, the belt cut so that it is dramatically narrower in the front than on the sides. She is stylish.

The hall is stated in the yearbook to have "spacious rooms, luxurious beds, personal services". At 1335 Louisiana Street in 1956 it was located across the street from the residence for the Phi Kappa Tau fraternity at 1332 Louisiana. My father was Phi Kappa Tau and lived in the Phi Kappa Tau residence that, as it turns out, was across the street from my mother. This was never mentioned and I only know it from learning the addresses in the yearbooks in which I've located them. According to the story that I have, this is not where they met.

Her story was that she had been living in a dorm and she was certain there were lesbians on her floor so she reported them to the house mother who told her to mind her own business and then all the bad people were against her for which reason she moved into a student boarding house that had one or two other male boarders and the landlady and her son. One morning she smelled smoke and on her way out to

One - 16

class she told the young son of the house he might want to tell someone about it but he forgot or didn't and when she returned the place was burned down and so she married my father.

"How old was the boy?" I one day thought to ask.

"I don't know. Maybe five."

Okay. That's just the person you want to tell, "I smell smoke, you better check that out." I've no reason to doubt this happened, my father always sat in silent agreement when she told the story, but the Lawrence, Kansas, census has her living in March of 1956 in a house that, according to Google Maps, is still standing, I'm looking at it right now in my browser, an old, three-story house that is one block down Louisiana Street from the Grace Pearson dorm in which she’d formerly resided. What was once a boarding house has since been converted into dark, depressing apartments, some rooms clad in pine paneling that's at least old enough to be the real deal rather than fake, the linoleum flooring so ancient it's the color of oven crud. A Hello Kitty doll (Hi, kitty!) set on the bed's pillows in apartment B is an exquisitely poignant touch, six dreamcatchers hung above to protect from the nightmares that might draft in through the window that's covered in blue plastic and sealed with gray duct tape all around. If one finds pine paneling too dark, the first floor is a little less daunting, however rundown, the flavor of pre-renovations observed in rooms that have plain plaster walls, original wood flooring, old window casements and baseboards. An enthusiastic welcome is given to university students with the dining room’s walls entirely papered in Busch Light, Corona, Bud Light Seltzer, Mojito, Magic Hat, and Coors Light cartons. At least I reason it’s the dining room because of the hutch built into the wall next a fireplace with a surround of old green ceramic tiles that extend onto the floor as part of the hearth. Built in 1925, now hosting ten bedrooms and four baths, it can be yours for between half a million and a million too much considering the fixing up it requires, plus the installation of functioning heat as portable space heaters are so frequently observed as to be a prominent feature. What can I say but that someone needs to move the space heater that's set on the stool next the bed in apartment B so that it's not touching the shirts hung on wall hooks above it or else they might end up with a fire as well.

In 1956, my mother, according to the March census, is the sole boarder and the only other residents are the landlady and her thirty-year-old son. In 1957, that household consists of the same landlady and son and three boarders, two of college age. I've no doubt the fire happened but my mother always gave me the impression the fire had burned the place down, which means it couldn’t have happened at the boarding house she was living at in March where the woman had a thirty-year-old son? My mother described the fire as happening, in July of 1956, so if it didn’t happen here this means she would have had to move between March of 1956 and July to the house where she is boarding when she will meet my father and where the fire occurred just prior their marriage. However, she never mentioned an interim boarding house. But she never mentioned a lot of things. I don't know how she meets him, that story was shaky so it never put down roots in my memory, but it was something something to do with an

One - 17

acquaintance on a sidewalk out front of somewhere and then they were forever together. As they met in July it would have been when my mother was living in the boarding house that burned. I’ve always trusted my mother’s story that the house burned, but I also know it’s unlikely that my mother would have made a move from one boarding house to another between March of 1956 and the beginning of July. Perhaps instead of the boarding house having burned down there had instead been some fire and smoke damage and it may be she’d had to move out but in March of 1957 the house was of a condition to be inhabited by the landlady and her thirty-year-old son who was not five and the three boarders. There are always two stories and I struggle to rectify believing both my mother’s story and the census’ stories. A search of the Lawrence Daily Journal-World gives no results for either a boarding house fire or a fire at that address in July of 1956, but the results may not be reliable, or it may not have been reported in the news. I wonder to where she might have moved after the fire in question as I carry out a cursory hand-combing of the paper in unindexed archives. My father never gave his version of their having met, not even to remark that when he first saw her he believed her the most ravishing creature in the world, and my mother always leaped to the end, after relating she had dated a rich boy with red hair and a red Cadillac convertible who was eager for her to marry him, she’d relate how he was devastated when she met and married my father instead after knowing him for just three weeks. Then, seated, she'd do her little supposed to be sexy jiggety jig wiggle, chickety-chick sound out the side of her mouth that meant they'd been hot to trot.

Which is why I was born less than a year later. My mother said that she had wanted to rub it in her parents’ faces that she was old enough to have sex and having it. This was why I was conceived. I was proof of sex had.

They married at the end of July 1956 so that means my parents met in early July. The long story is that her father, she said, was being a tight-wad on the amount of insurance money she was going to get for her burned belongings that she no longer possessed, he depreciated all items rather than making a claim for what they cost at time of purchase. While this was going on she either went to Chicago with my father to introduce him to her parents, or her parents went down to KU, I never got that straight, but now that I think about it the latter must have been the case, and during that visit my mother told her parents she'd decided she wasn't going to be a concert pianist, she was going to be a nurse instead, her mother's hysterical response being to threaten to throw herself down the staircase and kill herself. Indeed, I think my mother did eventually tell me her parents had come down to visit which forced me to change the mental movie I’d had for years of her mother threatening to pitch herself down the stairs in their residence, but as her parents were living in an apartment they wouldn’t have had stairs. Unless they’d moved by then. I don’t know. Anyway, it happened somewhere in Lawrence, my grandmother at the height of a staircase and her husband holding onto her to keep her from catapulting down them to her death. After the meeting with my mother’s parents, my mother only had peanut butter and crackers to eat over a weekend as her father held off a week on sending her allowance as punishment for her decision to become a nurse instead of a concert pianist, and

One - 18

my father came to the rescue and fed her and proposed and my parents eloped. I don't know where my mother was living after the fire, when she only had peanut butter and crackers for that weekend, which wasn’t the way things were as my father was buying her meals. That part was as confused in the telling as everything else. But there had never been anyone more impoverished than my mother who'd had to live on peanut butter and crackers for two days. One could be starving in front of her and she would have begged your pity with how her father's cruelty was such that she'd gone perilously hungry on a forever diet of peanut butter and crackers that lasted one weekend. No one else’s hunger mattered because of that weekend. She was the most destitute and starved person in the history of the world.

My mother was the youngest of three girls. Her eldest sister, five years older, was believed too plain, banal and graceless to possibly "catch" a husband, for which reason her parents taught her to smoke, hoping this would grant her sophistication, and still flush with money had purchased her a luxurious mink coat at twenty-two to dress up a dowdy demeanor (the census shows their next door neighbor on Scarborough in Cleveland Heights was the Hungarian proprietor of a retail furrier, ads in the paper show a nice place with merch as cheap as $268 squirrel capes and as expensive as $4000 natural wild mink, maybe they got a good deal as neighbors). It took six years after the purchase of the fur but she married in June of 1956 to a man considered beneath her station, and I'm not convinced that my mother marrying soon thereafter was entirely coincidental. The middle sister had married her first husband a little more than a year before in 1955, I believe she was the only one to have the full church bridal treatment, long white gown, no train (maybe it wasn’t fashionable, maybe it was viewed as too showy, House Beautiful’s guide for the 1955 bride shows a wedding dress with a short train), my mother and the eldest sister acting as bridesmaids in long gowns of an identical white brocade fabric but with bows that tied at a high jewel neck whereas the bride had a u-neck with an awkward lace flounce so the impression is one of demure conventionality. None of the weddings of any of the sisters were announced in the Chicago papers during an era when it was customary. The middle sister's husband soon proved to be problematic and they divorced, so we were supposed to pretend that disastrous wedding hadn't happened even though photos of it still hung around.

Three weeks after they met, my mother and father were married in gray, he in a nice neutral gray suit, she in a two piece dress, straight skirt and peplum-blouse in cool gray fabric with a pearl sheen, the blouse buttoned up the back with a white Peter Pan collar dressing up the jewel neck, white cuffs on the short sleeves, slim belt in the same fabric tightening the rather loose fit at her waist. A white headband hat adorned her hair. They had a maid of honor and a best man, and I don’t know who they were but no one else was told of the nuptials until after the fact and the choice of the best man and maid or matron of honor was last minute. The best man took two color photos of my parents, one inside the First Methodist Church of Lawrence (they didn’t regularly attend as far as I know) and one outside next to the sign so this is how I know where they were married. They were wed in days of torrid summer heat before air conditioning became the norm. They aren’t flushed or obviously sweaty in the photo, and my father’s suit is holding up beautifully, but their faces appear wan,

One - 19

wilted, and I realize it may be from the heat and look up the temperature. The high that day was 92 degrees Fahrenheit, cool in comparison to the three days preceding during which the temperatures exceeded 100 degrees, reaching 103 on July twenty-sixth. I was told they were married on July twenty-ninth but the wedding announcement sent out by my mother’s parents reads the twenty-eighth of July and that they were living at 526 California Avenue. If there was a California Avenue in Lawrence it no longer exists. Instead there is the short stretch of South California Street devoted entirely to a new development of apartments. This must be what was stated as California Avenue in the wedding announcement. Google maps shows a makeshift concrete barricade stands where there used to be more to California Street but was excised.

A spontaneous elopement—how did they have the time to find a place to live before the day of their unplanned wedding? I’m assuming my father was still living in his dorm when they decided to get married. As stated, considering the storied fire, I don’t know where my mother was then living. My mother had an engagement ring. Had my father purchased it before the wedding and taken it from his pocket and asked if she would marry him? Had he proposed spontaneously or with forethought or was it instead a mutual proposal and they purchased the engagement and wedding rings at the same time after the agreement or proposal, perhaps the day they got their license. Again, it was a quick elopement, they married immediately after agreeing they would spend the rest of their lives together, which was not long after the fire at the boarding house. If they’d managed to rent an apartment in the meanwhile, there wouldn’t have been time to furnish it. Where did they spend their first wedding night? Did they honeymoon at a motel? I never heard the story as it was never told. The story of their marriage was always the fire, the fight with her parents, that they’d eloped and there the story ended.

To a child, a week can seem an eternity, so I'd no idea how short a time were the three weeks between when my parents first met and they married. I knew, however, they'd flaunted convention, and the fact they'd eloped sweetened the lore of their rebellious romance even further. My mother’s parents didn’t want her to marry my father as he didn’t look all White, and my father had been seeing another girl who his parents preferred and thought he would marry. I don’t know who this girl was, my father never spoke of her because he never spoke of anyone. When I was eight and nine and a valiant defender of my parents, I applauded their defiance of the norm, imagining them as disrupters of the constraints of staid society because of their short romance and elopement, because my mother scorned the Leave it to Beaver (1957 to 1963 television show on how to be a good suburban) neighbors for not drinking during their morning coffee klatches, for which reason she opted out, and because my mother portrayed themselves as rebels I believed then that they were and that the elopement, the drinking, and her contempt for the world at large were all on a counterculture continuum of which I also knew they weren’t really a part. They weren’t 1950s Beatniks.

This woman I call my mother, this man I call my father, as a child I called them mom and dad. After the age of seventeen, after what they did to me, those times when we

One - 20

were in contact I never called them mom or dad, because to do so was too psychically abhorrent, the words would have stuck in my throat, I would have strangled on them. Around others, because my parents had to be called something if I had to speak of them, which I rarely did, behaving with the world as if I had no family, as if I’d simply formed out of the air we breathed, having no history, I called them mother and father as in-general, dictionary, impersonal identifiers. To even call them by their names would have been too personal. From the time I was seventeen on, the words “mom” and “dad” no longer even formed in my brain except as memories of what I’d called them. However, when later briefly in connection with my siblings, as they would have used the words mom and dad I would have as a matter of convenience in conversation.

My marriage story isn’t one to speak about. It was a low-key, an unadorned taking of vows in a church, and would have been more low-key and unadorned if my in-laws had not been religious. Without adornment, casual, it was normal if one didn’t take into account I lived with never knowing when a car would pull up and steal me away from the world, never to be seen again, as my parents promised me would one day happen, so that I was always stressed and looking over my shoulder. I didn’t speak about this with others, preferring to be a person formed from the air, with no history, but my in-laws had experience with my parents and without my knowledge had friends of theirs stand as guards outside the church in case my parents made an appearance. I didn’t elope but sometimes a part of me feels like I did as no member of my family was there.

As for my growing up believing my mother was almost a concert pianist, it took me a while to consider the plausibility of this. Doubts had surfaced before her eventual one-time confession of the injury done her when a famous something musician maybe conductor something at KU, instructor of hers of some sort, told her she would never be a concert pianist as she hadn't the strength and something something, for which reason the brief consideration of nursing, which would never have happened. The lore of her as dedicated like a vestal virgin to the divine altar of the concert stage was too strong to dead end on a few nursing classes, plus she wasn’t a caregiver by nature. When she was happy confessional drunk, she one day told me she had never wanted to be a concert pianist at all and that it was a relief to be able to let it go after the something something instructor torched that future, but the concert pianist was also the identity she kept polished and on display via her stories of this and her pianos—for we always had a piano. When we at first lived in places too small for the Mason and Hamlin that her parents kept as a maid-in-waiting wherever they were then living in Chicago, we had an ebony black upright Steinway we carried place to place to place to place to place to place, which I only later realized wasn’t a cheap toy piano, though wherever I got that notion I don’t know, perhaps from a remark she’d made when I was too young to later remember it ever having been said but had from then on defined the piano. We were daily reminded by our mother that she had been trained to be a concert pianist, the implication being that motherhood had diverted her from her genius and left her empty-handed, unable to use her fingers for their destined career. But what does it take to be a concert pianist? Performances and prizes. She had always spoken about the couple of people under

One - 21

whom she'd studied who had themselves studied under famous so-and-so names I didn't know, and it eventually occurred to me it was rather odd that none of these stories included her appearing even in a student recital, nor had she ever spoken of winning any competitions. I had been trained myself in music and one thing of which I was aware was that teachers traditionally liked to give recitals if for no other reason than parents yearly expected them as a return on their investment. I checked the Chicago and Cleveland newspapers for recitals in which she might have played, also hoping to thus dig up names of her teachers, and found reports of many recitals given by private teachers and in schools but none in which she appeared. The name of my mother, the fledgling concert pianist, didn't come up a single time. How could she be, at twenty-three years of age, seriously studying to be a concert pianist without benefit of performances or competing and placing in competitions. But I'd the image engraved in my mind of my grandmother at the height of some stairs, held back by her husband, the maybe embezzler, as she wrestles to throw herself down them crying-screaming over the prospect of my mother throwing away the brilliant destiny that had given them all meaning. Is it possible my mother might have won prizes but never mentioned them to me? No. Is it possible she performed in recital and her name never made it into the newspapers with all the other many piano students who performed in recitals? Perhaps, but I doubt this. Could she have been studying to be a concert pianist at the age of twenty-three without ever having had the benefit of any recognition or performance history whatsoever? Again, I doubt it. Could she have studied at Lawrence with the goal of eventually teaching piano or becoming a music educator? Yes, but it wasn't in her constitution to ever teach and she never considered it as an option. She held she was groomed to be a performer, not a teacher, to teach was beneath her, and she had us believe she continued to practice daily while we were at school, driven by her dedication to what had been denied her yet survived in her soul, but I would only ever hear fragments, she would never play a piece through. She never once performed for us, she never played for us.

My mother, the almost concert pianist, who always had an expensive piano, never once performed a piece of beloved music on the expensive piano for us.

We each have dreams of ourselves, conceptions of our best selves, of what we fundamentally are, and I'm not going to deny my mother her definition of self as a musician. How much this depended on her or her parents I don't know. They undeniably believed enough that they sank a not inconsiderable sum of money into the Mason and Hamlin and lessons, though I understand her sisters had lessons as well. My mother, I trust, practiced assiduously until the goal of the concert pianist evaporated, but I don't know whether all her practice was from passion or duty, whether the dream of being a concert pianist had belonged to her or if it had belonged to her parents and been absorbed by her. Even if she never had what was required to be a performing or professional musician, she was still a musician, though she had no interest in any genre of music other than the standard Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms, with a touch of Chopin and Handel. I was trained musically, and I married a musician, and she never spoke about music in the way that I’m used to musicians speaking about music. She never spoke about theory, never discussed the whole of a piece then broke it down to examine how it worked as a whole and in

One - 22

parts. She didn’t speak about differences between performers and performances and conductors except to rarely name a favored recording. She didn’t like the famed pianist Glenn Gould but never said who she did like. She never reveled in discoveries of new recordings and never shared any musical recordings for sake of their magic. She never said, “Come, listen! Listen! Isn’t this beautiful!” Rather than discussing music she would talk about how she used to have perfect pitch but a record player of ours ran a little slow and that ruined it. Her relationship to music was entirely personal and introverted, centered around her rather than her in relationship to the universe of musicianship and music.

I have a photo of her sitting at the Mason and Hamlin as a youth. It’s Christmas. She’s about fifteen or sixteen, her hair not styled yet in the bangs that she would begin to wear when she was seventeen and would keep the rest of her life. Instead, her hair is all one length, parted on her left, swept over and held back by a ribbon on the right, full-bodied and gently curled, shoulder-length. The clothing she wears resembles a school uniform but must have been the fashion of the day, a dark jacket with white piping, brass buttons, white blouse with a dark string bow tied at the neck, pleated plaid skirt, white ankle socks and what would have been teen-stylish saddle oxfords the white leather smudged with scuffs. The photo is landscape, horizontal, and takes in a fair portion of that end of the living room. On the screen right is the Mason and Hamlin, the top propped open, music books open on the music rack, a lit floor lamp beyond the piano bench upon which she sits facing three-quarter profile to screen left. Her left hand rests lightly on the corner of the piano bench, her right hand in her lap. To the screen-left in the corner of the room stands a full Christmas tree, lights aglow, regally decorated with assorted balls and shiny tinsel. Beneath it are presents, medium and large boxes wrapped and tied up with ribbons and bows. Perhaps an album of music rests among them against the base of the tree. Before the tree, against the screen-left wall of the room, is a large armchair single-piece wingback upholstered in floral tapestry with Queen Anne-style legs, before that a side table with perhaps a marble top upon which rests a small box and a glass ashtray, then before that in the very left corner of the photo a glimpse of an upholstered skirted sofa. A massive oriental rug occupies the open space of the floor between the photographer and the piano, a smaller oriental rug beneath the piano bench. The living room is quite large with four large windows spanning the wall opposite the photographer, behind the piano, plus two windows in the screen left corner, all dressed with wooden venetian blinds that are open and open floral drapes. As it is night, the effect of the open venetian blinds on these four windows, behind my mother, spanning three-quarters the length of the entire photo, is of a black field with narrow horizontal stripes, and the broad horizontal stripes of the window casement adds an interesting visual texture. I wonder if they first staged the scene for the photo with the drapes closed then opened, the blinds closed then opened and decided this would be the shot. It’s a very nicely composed image that could pass for a professional sitting. My mother neither smiles nor frowns, her face expressionless but not vacant, she gazing into the distance away from and beyond the photographer.

Perhaps because of the piano, when I was a youth this is the interior in which I imagined my mother growing up, and when I was a child it represented for me

One - 23

Chicago and the perfect apartment because my mother said they’d lived in an apartment in Chicago and I was always confused on all points of her history. At that time they would have been living in a house but I don’t know what house that might have been except that in the mid- to latter 1940s, maybe 1948 or 1949, it could have been in either Chicago or Cleveland, as they were in Chicago perhaps in 1947, but were in Cleveland by 1949.