Return to Table of Contents for films

If one didn't grow up in mid-twentieth century America, I'd question if one would have some essential deprivation of material that Anna Biller's films examines, or if it's enough to experience those eras alone through the analysis of her lens, except that Anna Biller herself isn't of a generation to have been ingesting mid-20th century America with the intimacy of her morning cereal--which brings up one of the aspects of Biller's cinema that marks it as decidedly different from many others, and this is that each one of her films is not only a stand-alone work that may be viewed as a thing unto itself, they are also a cinematic analysis of not only the messages purveyed by earlier media and their language of style, but also their influence on contemporary views. Though every thoughtful piece of art is arguably a commentary on society and culture, Biller's method is peculiarly deceptive, unlike any I've viewed previously. One may have the feeling of being dropped back in time for an immediate and direct experience of the media being examined, but the critical lens removes us just enough, due Biller's peeling away all that distracts from the authentic core, so it is as an alternative fever dream. Among her influences, Biller has listed Fassbinder, who I mention now as his method of critically analyzing culture and cinema in his own films is as close a comparison I can make to Biller's work, and I'm not sure I would have considered Fassbinder as an obvious influence had I not read Biller giving him as such, among others. Then one sees how it is undeniably so. However different Biller's cinema is from Fassbinder's, it is removed from naturalism in a way very like Fassbinder's, such as in The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant or The American Soldier. In naturalism, the goal is to be as close to reality as possible. It may seem odd to speak of "naturalism" and Viva in the same breath but Biller's portrayal is authentic, and with Biller, as with Fassbinder, there is always a gap between action and scene and what it's intended to invoke. The space between belongs to emotionally filling in what standard film language can't typically handle, which strategically belongs to poetry. Biller, as with Fassbinder, is a poet.

Viva opens with an ariel view of a suburban neighborhood very like what one might have seen in a 1972 film, with a voice-over setting up the story as being about a housewife during the sexual revolution, just as might have been had in the 1970s. We have the feeling of a time-capsule being opened so that the scene that liquidly spills out is not only verbatim but original. From the aerial view we have an immediate and jarring cut to a woman (Biller as Barbi) in a bathtub. The appointments are of the time--the green tile surrounding the tub, the burnt orange towels with their abstracted floral design and fringe, the gently crescent shape of the pink bar of soap. The woman is relaxing with a glass of wine, reading a hardcover book, Decorating with Crochet. Would your everyday woman have been reading this book in her bathtub? No. But, the crochet book is essential to the zeitgeist of that era and yet would never have been in a 1970s film. We would have seen the product of the book, crocheted clothing, much of it for young women, or afghans, but the fantasy involved in the crochet literature and its images is very different, belonging to the world of make-believe, the idealized costumes and settings by which one might craft the future perfect in which one finds true life and love, and we know that love is important to Barbi for we observe one of the pillows in the book has the word "love" crocheted on it.

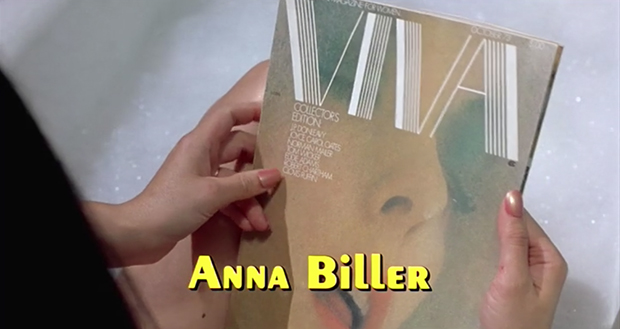

Barbi puts down the crochet book and picks up a magazine, Viva, the 1st edition from October 1973 (though the movie is set in 1972) which features the famous author Joyce Carol Oates, but on the cover is a close-up of a woman with her mouth seductively parted. Viva was a magazine for women that was supposed to be to them what Playboy was to men, combining soft-core porn with intellectually stimulating material.

She turns to a story of Victorian soft-core porn (the Victorian era already recalled through the crochet, however modernized), and when Barbi does so her body is artlessly exposed so that we see her breasts, but this isn't the nonchalance and artlessness of naturalism. The maneuver replicates artifices of film and photography that are a means to reveal the body, but also manages to defuse them because the move is blatant yet innocent. It acknowledges by mimicry but is also thus an observation on sexploitation genres.

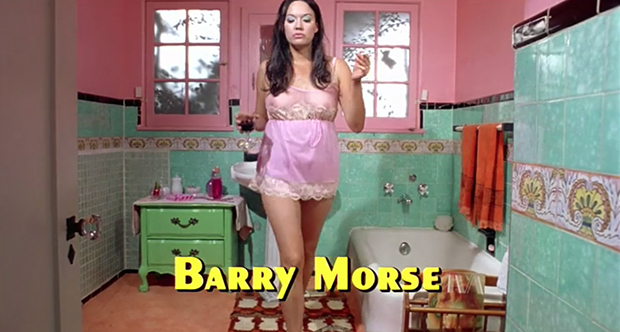

Cut to Barbi standing outside the tub on a hand-tufted rug on wall-to-wall shag carpet, her feet already in high-heeled mules, she picking up the lacy froth of a pink baby-doll negligee. Then we've a full-body view of her dressed in the negligee in a bathroom that is decidedly the fruit of the 70s but would hever have been filmed or photographed as the 1972 dream bathroom. The dream bathroom would never have had two types of mismatched green tile. The orange carpet on the floor attempts to match with the burnt-orange towels, but conflicts with the hot pink paint that Pepto-Bismal swathes the walls above the green tile. The scene makes for a far more interesting Barbi-as-Venus on the half-shell of her bathroom than would ever have been commercially envisioned in that time, for it's instead the bathroom where the desires of the heart, inflamed by the commercial vision, meet and produce an off-kilter child that must always be denied in the hindsight that soft-focuses all imperfections.

Barbi at her make-up table, we can taste the lipstick she applies, and Biller mindfully embellishes with the succulent "Mmmm" of a comma to the action as she purses her lips with satisfaction. Next we see her, she is upon her stoop, having just exited her home. She poses just long enough for us to appreciate the trappings of her facade--the make-up, the clothing--before proceeding to her dreamy bright red convertible, with a veritable hop skip and a jump, and from there she drives off into the supposedly real world.

All of this happens under the credits, which is a creative tour-de-force, the amount of content flung at us already massive. This is a very different kind of film. The kind of film that remolds brains.

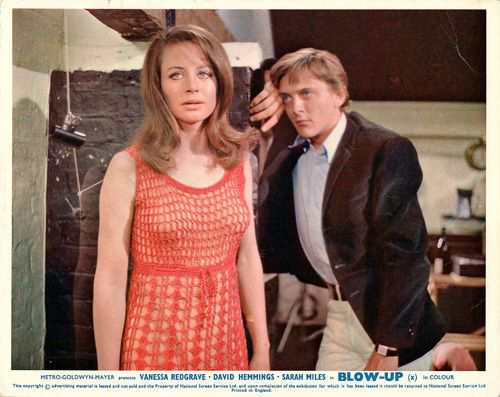

Cut to a backyard-with-pool set that reminds of the Sunny Dunes Estates advertising in Antonioni's 1970 Zabriskie Point with its stilted mannequin attempt to project commercial fantasy tropes into a charade of real life satisfaction.

Biller's Viva may fit into the comedy genre, and be conceived of as parody, but it's not parody, it's not satire, and there's no trace of the sardonic or even mockery. The intentional self-consciousness of language and timing remove us from the stage to the interior dialogue of an era and culture mimicking a collectively-commercially sold fantasy that was desperate to be adult and refined but is instead infantile and puerile in the manner of one whose attempts to hide a fear of inferiority exposes it. The first big joke is the Dewar's 2-liter jug of whisky, worth about $300 in today's currency, which is brandished as breakfast between a blonde woman's "jugs", garnering a broad, fake, smiling, open-mouthed laugh from both her and her husband, and is an anti-joke, as are most of the jokes in the movie, which are of the class of Playboy humor that was decidedly unfunny and presented here with a crystal clear authenticity scathing in its critique. The owners of this home are Mark, a television actor, and Sheila, a housewife, and they are Barbi's destination on a day when her husband, Rick, has abandoned previously made plans with her and gone in to work.

Sheila picks up a July 1971 issue of Playboy which featured an interview with John Cassavetes. One of the tired jokes about Playboy that is actually true is that it could be worth reading as it offered good, complex interviews with interesting individuals. In this issue's interview, Cassavetes discussed sex and nudity on the screen.

Cassavetes: ...I don't think there's anything morally wrong with seeing a nude body on the screen...I don't think I've ever seen a good picture heled or hurt by nudity, but I've seen lots of pictures where nudity was self-conscious, where it was apparent that the actors were uncomfortable. Maybe I just can't handle the idea of seeing something on screen that's so personal--and dirty.

Playboy: Dirty?

Cassavetes: I think sex is dirty. I like it dirty. And the thing that makes it dirty is to grab something clean and defile it. Yeah. Most movies can't convey that illicit kind of thing, even though they try...

Playboy: Why do you think nude scenes have become almost obligatory?

Cassavetes: The reason there's so much nudity in movies today is that we're becoming a voyeuristic society, and producers are responding to that demand with a great big supply. Not only are we becoming more voyeuristic, but I also think we're starting to lose faith in the idea that one man and one woman can totally pease each other in bed. Sex is becoming something of a community activity; more and more people have to hop into the sack together in order for all of them to achieve sexual satisfaction. I wouldn't want to interfere with anyone's right to conduct orgies, you understand, but I personally think that kind of thing finally robs sex of all its delicious and very private pleasures. When sex becomes commonplace, when the girl you want is trying out half your suburban community and the same is true of you, where are the romantic and secret pleasures you need out of sex? I don't like sex to be ordinary and rational and organized and sane. But I don't like sex in groups and I believe in--and practice--fidelity in marriage...

I've no idea how Biller might feel about Cassavetes, a director who could seem very male-oriented in his choice of material, but I love his realism and his depictions of women, such as in the gut-wrenching A Woman Under The Influence, and Opening Night, both featuring the inimitable Gena Rowlands. As there's a good deal of nudity in Viva, and Viva explores sex outside of marriage, it's interesting to consider Cassavetes' remarks on these subjects and realize how anti-voyeuristic and uncomplicated the nudity in Viva feels. It simply is, as it is a great part of the subject being examined, rather than slipped in as extraneous, illicit candy, or a dark alley side entrance to an "art movie". Biller attacks the subject straight away with the cursory revealing of Barbi's breasts in the bath, and will now through the subject of the camera's relationship to sex. The conflict is always between what Barbi feels as opposed to how male-oriented culture and entertainment depict a woman. Unlike in a realistic film, the exposure of Barbi's breasts in the bath wasn't entirely naturalistic, it was self-conscious in the knowledge such a shot would be in many films voyeuristic and titillating, but Barbi was herself not self-conscious, she was only a woman in her bath looking at crochet and soft porn and the real subject for consideration was how she could go from the one magazine to the other as if the subjects naturally blended together and how this might be so.

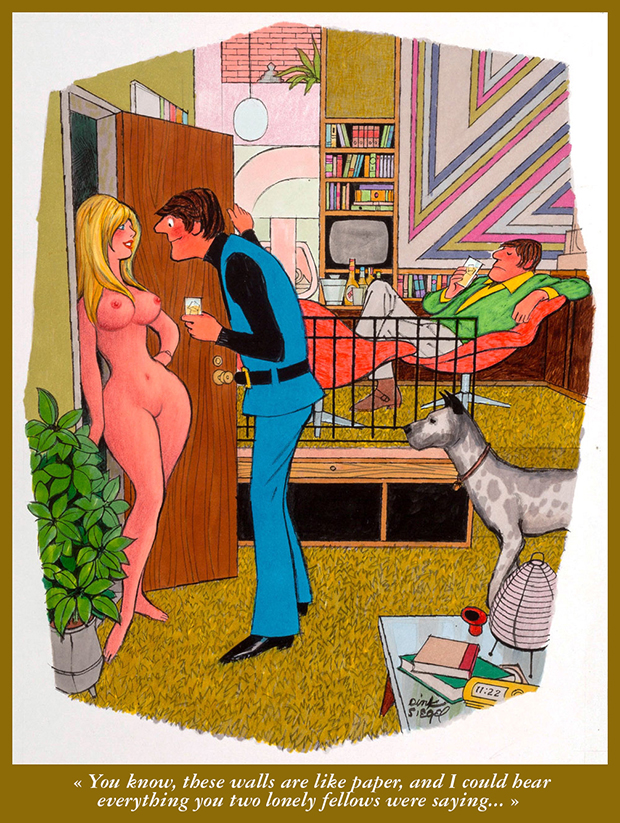

Mark has gotten a camera and is eager to finally use it. The literature on the patio is Playboy, and when he does now use his camera it's to take photos of Sheila and Barbi with open-mouthed awe at his wild, good fortune of filling his film with such babes. One may be reminded of the photo spread in the Viva magazine in which the Victorian photographer eventually dropped his camera down so that it was suggestively on the level of his pelvis. But it was Sheila and Barbi who initially compared themselves to the women in Playboy and they enjoy Mark taking their photos in their swimsuits as if they are models and could appear in Playboy's pages.

Mark, however, having mistaken taking photos of Barbi for taking possession of her, transgresses boundaries by grabbing and squeezing Barbi's buttock, and she backs away, astonished, while also trying to not draw Sheila's attention to what her husband has done. Made uncomfortable, she slips back on her shirt when she sits by the pool, and when Mark questions her about how her life is going she complains about her work, that it's always the same, "A little dictation, a little pinch on the behind. You know, the life of a secretary." When he responds it sounds fascinating she dryly replies, "You think so? You should try it sometime." Still, Mark presses on, telling her how she's a beautiful woman and men "can't help it" if they respond to that. He then even goes so far as to tell her that he now prefers brunettes over blondes (Sheila is blonde, Barbi a brunette), as brunettes are more intense and sensual.

After a swim, they sit down for lunch, which Biller uses as an opportunity for a change in costume to chiffon dresses. Indeed, there are four full costume changes in this section, which has a disjointing, chaotic effect that compounds the purposefully stilted sensibility of the film. Biller so loads the eye with clashing and complimentary mixes of color and texture that, however pleasing the artistry involved, the senses jangle trying to interpret what's happening. This isn't a criticism. She makes one aware how simplistic and invisible is typical set design, how it doesn't communicate emotionally and thus not faithfully or evocatively.

Sheila, jealously sensing Mark is too interested in Barbi, reminds him of how great their sex life is, which shuts Barbi out of the conversation. In response to her discomfort, Mark calls her a baby and takes away her cigarette and drink of whiskey. He and Sheila laugh uproariously.

Suddenly we are inside, Mark dressed in a suit, Sheila in a red babydoll nightie, and Barbi in a towel, she perhaps having bathed after their hot day by the pool. Mark and Sheila both drinking, as Barbi enters she asks if she can have one as well and it's obvious her desire to be accepted, to be a part of the group, bored and alienated with her husband working all the time, which she had earlier complained about.

Taunting Barbi with their coupledom, Shelia and Mark intimately cuddle. Mark teases Barbi that she's all undressed with no place to go. When Sheila exits to get Barbi a dress to wear, Barbi stands and, eyes fixed on Mark, drops her towel, showing her breasts. Why? To thrill him? But it seems more Barbi determining in this way she'll meet their challenge as to her being childish and not as worldly as them, for if this had been to thrill Mark she would have attempted to cover herself before Sheila returns with a dress, which she does not. This was Barbi's effort to show that she isn't a child, that she is as worldly as they are. She puts on the gown Sheila has brought her, Sheila slipping on a long black gown, and Mark picks up the huge jug of Dewar's and positions himself between them. The two women draped over his shoulders, Sheila says, "Now, how about that movie?", and the three laugh as though she has just told the funniest in-joke ever, Mark brandishing the bottle as if they are being photographed for a Dewar's ad.

I'm going to be periodically discussing things that may seem extraneous but aren't. Notice the white culottes that Sheila wears in the scene beside the pool. By culottes, I'm not talking about the split skirt that was essentially very wide leg short trousers, usually hitting about the knee or below in order to be fashionable and sometimes called gauchos. Instead, she wears the type that were very short and had a flap in front, so from behind one appeared to be wearing shorts, while the flap in the front camouflaged with the unsuccessful pretense of a skirt, not very effective as the front flap would often end up sticking up awkwardly. These were popular not so much around 1972 but in the late 1960s when pants on women were still absolutely forbidden in a majority of settings. In 1969 pants were still not allowed in schools. They were rarely permitted at work. In any occasion that required a woman to be even moderately dressed up, pants were still looked down upon if they weren't strictly forbidden. Modesty had nothing to do with it, as if they might be more revealing with outlining the buttocks. Pants certainly weren't as revealing as most skirts. They were instead considered masculine. Sheila and Barbi never wear trousers; they are almost always in either the popular short dress, short skirt-dress combo that had the appearance of a blouse and skirt, a dress that had the appearance of a jumper and blouse, or the long gown. At one point Sheila says she's 29, which would place her as born in 1943. Sheila and Barbi--as well Mark and Rick--belong to a generation prior the Baby Boomers, and though Sheila and Barbi's attire is definitely "sexy", it is conservative in respect of honoring what styles belonged to men and what belonged to women. There are no jeans--which even conservative or moderately conservative Baby Boomers might not have then worn even though jeans are considered synonymous with the late 60s, their explosion in popularity such that they eventually became almost a uniform. That was a little later and for youth, when jeans were considered egalitarian and had yet to go through the designer mill. One could wear jeans every day whereas if one repeated the use of a dress then it was noticeable, and the way the fashion industry worked in concert with the middle class, women and girls were expected to not repeat clothes too often, certainly not on special occasions, and were still pretty much required to have new wardrobes every season and certainly every year.

That these individuals belonged to the Silent Generation is important. They were too young to have fought in WWII and too old to be children of the counter-culture. They were "between", Sheila and Barbi being the younger siblings of the parents of the Boomers. Hugh Hefner was born in 1926, and so preceded the Silent Generation by only 2 years. Timothy Leary was born in 1920. These cultural vanguards were exceptions to the conservative rule, and despite the Beats coming out of the Great Generation, and younger members of the Silent Generation of an age to be early Hippies, however positioned this generation to lead in feminism and civil rights, entrenched in conservative, almost exclusively family-oriented suburbs they seemed often having to continually stretch to keep up with the times. Though Beats and Hippies were often depicted in entertainment, they were never any more than a minority. Consumerism and advertising ruled supreme.

Barbi works as a secretary. In 1970, 43 percent of women worked, but the job offerings were limited. The 9 to 5 reliable queen of women's employment in the white collar class was that of the secretary, which was a respectable career if one was older, and vaguely respectable if one was younger, because the secretarial job, however essential, was also seen by some as an opportunistic gateway by which a woman might luck into marriage with the boss or one of his associates. While feminists wanted a world of opportunities for women, antifeminist conservatives reviled such progress as destroying the nuclear home of patriarchal breadwinning father and the wife whose sacred office was to bear and tend children and keep the hearth fires burning. The working woman was taking jobs away from men who needed to support their families. The career woman who didn't want to be the stay-at-home mother was also viewed as masculine, anti-feminine, and, horrors, likely a closet lesbian, which threatened the sacred institution of the nuclear home fiercely protected by the ironically subservient wife. If the working woman wasn't "masculine", her working days were seen as a temporary state on the way to her marrying and having children, which was a reason to not take her seriously, or, if she was a divorcee, remarrying by insidiously stealing away the gullible, vulnerable boss from his honest housewife.

Women characters in film had jobs, and even interesting careers that bordered on the then exotic (by this I mean upper tier professional), especially before post World War II America had shifted the woman out of employment she'd occupied while men were at war and positioned her back in the home with her Baby Boomer children, but a woman seeking work in the newspaper's employment section in the 1960s and 1970s was confronted with pages of receptionist, clerk, secretarial and stenographer ads. The greater portion of the working world was closed to the mercurial, non-intellectual woman who was still comprehended as a creature guided by her feelings, intuition, and other weaknesses of her sex (Biller has, on Twitter, complained her films have been discredited by men as interesting by way of the intuitive accident, which fits in with this Nietzschean, misogynist view of women). The woman's role was to be the helpmate to the boss, rather than the boss herself, and it's interesting that Biller introduces this helpmate aspect in the film before exploring Barbi's relationship with her husband. The secretary's standard office duties included making coffee and tidying up, serving as the office wife as it were. She was even expected to be so intuitive as to understand what her boss needed before he was aware of it. Boundaries collapsed with sexual harassment when the boss expected more, as the working woman could not escape the stereotypical role of her gender as submissive to and owned by her more powerful male boss (except in the case of those who saw her as the temptress attempting to steal the boss from his home).

For some reason the ship was a sometimes popular masculine theme, and Biller has picked up on this and focused on the nautical to decorate this office that would be, aside from the preponderance of flowers, fairly standard, the furnishings all dark leather and wood, dark leather and dark wood being considered masculine. Photos of the boss' family are displayed so to showcase him as the proper family man with a wife and children at home.

As Barbi takes a letter, a long-haired "hippie" with a peace symbol about his neck bursts in asking if it's the welfare office, and the boss angrily directs him to Room 222--which may or may not bring in one of the other few jobs available to women, that of the school teacher, "Room 222" having been a television series on teachers at a high school that ran in the early 1970s. The confrontation between the hippie and establishment was probably in all the entertainment of the day, but for some reason I'm reminded of the 1973 film Blume in Love in which a divorce attorney is discovered by his wife sleeping with his secretary, and after their divorce he attempts to befriend and win her back though she's entered into a relationship with an unemployed musician she met at the welfare office where she is a social worker. Via the musician, the former husband and wife both seek to escape the middle class mold, and learn about themselves. The hippie, representing spiritual exploration, was also tied up with the sexual revolution, and both chaffed against and colluded with the sexual revolution values of the corporate, establishment Playboy world. Rather than either revolutionizing society for women, they each had different frameworks for the woman as sex object and caretaker.

Barbi is positioned as a character in a Playboy comic, unwitting and innocent, her skirt accidentally hiked up to reveal her thigh and the garter holding up her stocking. After the intrusion of the hippie, the boss gives into his lust for Barbi, grabbing her and beginning to undress her. The Playboy type fantasy has her wide-eyed with surprise, the boss making an infantile joke about his liking her for being on top of things as he fondles her breasts while holding her on his lap. When she attempts to leave, he declares he's not through "promoting" her yet, and Barbi sighs,, frustrated and dejected, but Biller cuts away before we can tell if that dejection includes resignation. The joke meets reality when in the next scene we find Barbi was fired, presumably because she refused to be "promoted", her boss learning she is married.

Women had no protections against sexual harassment in the working world. The phrase "sexual harassment" didn't come into use until 1975, and was considered an interpersonal problem. A woman who was harassed had no choice but to put up with it or quit and find another job, then had to rely upon her harasser for a good recommendation.

Dressed in a transparent, light pink peignoir, Barbi prepares martinis with olives, the large topaz color jewel on a ring she wears flashing bright in the camera. She announces she's ready, the doorbell rings, and she answers it, exclaiming with spritely surprise, "Rick!", though this is her husband, and he exclaims in return that it's been too long. As it later turns out her husband seems often to be away on business trips, but at first it's difficult to tell if they might be role-playing, for books of the time were published for housewives that suggested different scenarios for spicing up one's marriage. However, when she asks him how his day was the scene tumbles into the awkward and decidedly intentional feel of fantasy role play that is part of the exceptional and dream-like nature of the film.

This curious introduction of Barbi's husband actually is suited to and aptly describes the world of the Barbie doll. Like Barbi, the Barbie doll is middle class. It could be argued that Barbi is even toward the upper tier of middle class, having a good deal of disposable income, a nice home, pool, and sports car, as did Barbie have also a potentially nice home and pool and sports car if one could afford to purchase them. Though it's been argued that Barbie wasn't a sexist toy, and it's true little girls loved her for not restricting them to the perpetual mother of the baby doll, she was inspired by the German doll, Lilli, which was a physical representation of a comic strip call girl. Lilli had not been fabricated for little girls, instead she was for men, sold in such places as adult-themed stores, an ornament for the car, a party favor at a bachelor's party, a suggestive tease of a gift for one's sexual partner. Though she was a sexual mascot, Lilli didn't have to be hidden in brown wrapping paper, and little girls discovered Lilli and adored her. In the hands of Mattel, Lilli was transformed from a prostitute into the middle class Barbie, a vehicle whereby a girl could fantasize her future as a women without the baby, but her Lilli origins still sizzled in her seductive form (though not in Midge, her cute friend with freckles) and just what was Barbie to do as a woman if she didn't get pregnant and have babies and was too emotional to be an astronaut? She wore clothes, lots of clothes, an outfit for every occasion, because an outfit made one's life. As a single woman, Barbie could be--well, since she was beautiful and sexy and had a lot of high fashion clothes, how about a high fashion model? As a single woman, Barbie needed a boyfriend, thus the Ken doll, whose early incarnation resembled Barbi's husband, Rick. But Barbie was also supposed to be equipped ultimately for marriage, which meant Ken was also potentially the husband doll. Though Barbie would be provided a little sister, she had no parents. She was out in the world on her own, with her friend Midge, and Ken, and that relationship with Ken was an awkward one in the hands of an elementary school or preteen girl. They were male and Barbie. They didn't know each other, not really, just as Playboy cartoons depicted marital and partner relationships so as to only have one commonality and basis for a relationship, the ability to have sex. Barbie could get married. The requisite wedding dress was sold. What happened after the wedding? It depended on the child handling the doll, but Ken arriving home might very well ring the doorbell if in some play sessions he was the boyfriend and in others he was the husband.

There is no back story for Barbi and Rick, and how Ken communicates with Barbi is intentionally as slim and flat as any stereotypical interaction between a Playboy cartoon couple who have not much to say to one another before and after sex, the difference being that Barbi is always internally reflecting on her situation, trying to make sense of it within the conventions of the time.

After a long hard day at work, Barbi's husband expects to come home to a woman who will fix his drinks, light his cigarettes, exchange his street shoes for comfortable slippers, prepare his meals, and be the desert, the trappings only varying based on whether one was using, say, a conservative or Playboy model. Where the two differed, in respect of the home, was a matter of aesthetics. Rick tells Barbi she's the perfect little woman. When she asks how his day went he relates since he started working overtime sales have gone up and they'll soon be able to afford a cabin and fishing boat. She tells him she was fired as her boss discovered she was married and Rick assures her that her job is being his lovely girl. Barbi smiles and welcomes this flattery but she'd also like to have a job so that Rick didn't have to work overtime. Rick says his business trips are his way of unwinding--skiing, drag racing, playing golf. When Barbi asks if he thinks she'd be a good model, he says her she could do anything she put her mind to, then tells her it's time for her to put her mind into giving him some good lovin', which they do on a white fake fur rug before their fireplace.

"All my men wear English Leather. Every one of them."

I've no idea how colognes and perfumes are marketed today or their popularity, but a standard mid-20th century gift for men, when you didn't know what to give, was cologne. Dads got Old Spice. English Leather was marketed to women for the men in their lives, "every one of them", who wore English Leather "or nothing at all". A 1960s commercial for English Leather shows a woman on the night deck of a ship, discussing how she thinks men are beautiful, even those who have been unkind to her, and they all need what women can give them--love, understanding and English Leather.

The sales hook for English Leather was the sexual revolution woman who had more than one man and didn't mind being abused because she understood that's how men were.

If I go into this it's because this scene has Sheila in a red gown, Mark in a red dress shirt, insensibly dressed for their outing in nature, but here they are, Sheila advancing from the trees with a tray holding Crown Royal and a birthday present for Mark that is, I believe, a bottle of English Leather cologne.

Advertising is almost always full of absurdities that go unnoticed in the viewer's uncritical purchase of the fantasy presented. Biller ensures we mark the bizarre by having Mark in only his dress shirt, and the nature landscape not fantasy picturesque with painted green grass.

Shelia having presented her gift to Mark, she says she needs a new outfit to a barbecue that Barbi and Rick are having, and Mark complains about how expensive she is.

The book he's reading at the beginning of the scene is Doctor Cobb's Game, partly based on the Profumo scandal that involved Britain's Secretary of State for War, John Profumo, a 19-year-old showgirl-would-be model named Christine Keeler, and maybe some exchange of sensitive government secrets that fell into the hands of the Soviets, or maybe not. From what I understand, Doctor Cobb's Game, which involves reviving the health of England with a sex magic revolution, could be best described as a book ripe for the Playboy era, and yet the author's work never made it into Playboy.

Ritz crackers with mustard, pickle, and a spritz of white Cheese-whiz topped with rolled lunch meat. Deviled eggs sprinkled with paprika. A salad of greens topped with bright sections of green and red bell peppers. Potato or macaroni salad heavy on the mayonnaise. Swedish meat balls. A lime green jello mold. A cheese board with chopped cheddar, pepper jack and possibly Gruyere surrounded by toasted triangles of bread and a sliced baguette. A bowl of diced cooked carrots and green peas. Cheese and potato puffs. Potato chips. Mixed nuts. A great bowl of pale green and pink melon balls and bright red strawberries surrounded by shrimp-like sections of orange poised upon the bowl's lip. A bowl of shrimp next to a dish of shrimp sauce. Pineapple slices topped with a square of ham and a green olive. 1970s magazine photos of cocktail food never looked as vivid as Biller's presentation of the offerings at Barbi and Rick's party--the one for which Sheila needed a new dress, so when Mark compliments Barbi on her outfit and she remarks it's an old thing she only wears around the house we know Sheila will be paying attention, she already flirting with Rick as he mixes her a Pussycat, complimenting him on his physique and ruefully comparing it with Mark's beer belly. If Barbi's problem is that she never gets to see Rick because of his working all the time, Mark has been laid off from his television show and is at always at home, which Sheila doesn't like. To occupy herself, Barbi says she's thinking of getting meaningful work, like being a model. Over on the sofa, the two men discuss Rick's new TEAC (a big name in the 1970s) while Mark sexualizes his Panosonic, saying that not everything that makes nice sounds has to be expensive, as he glances over at Sheila. It's a bit of a shock when Rick announces that after he trades in his car for a Camaro he's thinking of getting a color television, for the hyper-saturated colors of Biller's film make it difficult to imagine that people were watching a black-and-white tube in the 1960s and 1970s (by 1972, however, half of America's households had color television and I'd imagine that Mark and Barbi would have had one already, though I should note that I don't believe we ever see a television set in their home). Mark's philosophy is that one lives and loves today and pays tomorrow, why worry about money, which is the American Way. Rick says Mark takes the "live and love" stuff too far, like his cologne (which would be the English Leather he was given for his birthday). When Mark says women love it and Rick should consider wearing it for Barbi, Rick responds that Barbi likes him as he is.

At the scene's end, Mark sits on a lawn chair behind Barbi and is so sexual with her, gripping her waist, that Barbi, obviously uncomfortable, looks pleadingly up at Rick, and he tells Mark to back off. Sheila pulls Rick down on top of her, telling him to ignore Barbi and Mark, which defuses the situation as it is treated comically. But Mark's manhandling of Barbi isn't a joking matter. He routinely and cavalierly oversteps boundaries, as do most of the men in the film, and Barbi often ends in doing little to defend herself in order to not cause a crisis. Besides which, her sexual rights are ambiguous as she is expected to be submissive and thus has little in her arsenal for self defense.

Barbi finds the life of the housewife unfulfilling. Having expected her desire for meaning to be satisfied in her relationship with Rick, her husband as the center of her life, when he ends up being an absentee husband, working from early in the morning until late at night, she is unmoored. She has let go the housekeeper and cleans and learns to cook but these activities aren't enough. We aren't shown the television and magazine ads that reassure Barbi that spotless floors, dishes, glassware, windows, and clothes, are her path to happiness, the admiration of friends and neighbors, and the adoration of her spouse, but the message is clear enough, as well her boredom, with Barbi vacuuming carpets that are already vacuumed, polishing furniture that already gleams, and finally settled on the kitchen floor with a bucket and can of Easy-Off degreaser.

Sheila having encouraged Barbi when she said she wanted to find something meaningful to do, such as being a model, Barbi has a glass of wine, takes and bath, dresses for success in white go-go boots and a dress with a red top and red-and-white checked skirt, and goes looking for work. When she arrives at the entrance to the Gladstone Modeling Agency, the sailors outside, ogling her and remarking on how she's classy, may make Barbi feel that she is on the right path.

But Miss Marker, Gladstone's assistant, dampens Barbi's hopes with her not being a young girl any longer. Still, with the right hairstyle and make-up, she might get work as a catalogue model and an actress in "art movies". Marker advises Barbi to return with a photo portfolio and then offers to do the photographs herself. Sexual harassment is equal opportunity, and Barbi, who had been assaulted by her male boss at the insurance company, is propositioned by not even a prospective boss but his assistant. Barbi draws away from her kiss and one wonders if her refusal to reciprocate has blown Barbi's chances at the Gladstone Modeling Agency, not that this would be a bad thing. We have been given a glimpse, behind the scenes, of a model having her "lawn" manicured for a photo shoot (primed for this already by Barbie having told Sheila, at the party, that the look of her manicured lawn was very "in" that year)--but then we are not entirely sure what Barbi expects from a career as a model, whether or not she would be happy with soft porn. She is, after all, an appreciator of the magazine Viva. But it is difficult to imagine her comfortable working as a soft porn model.

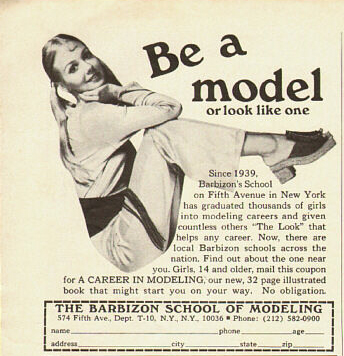

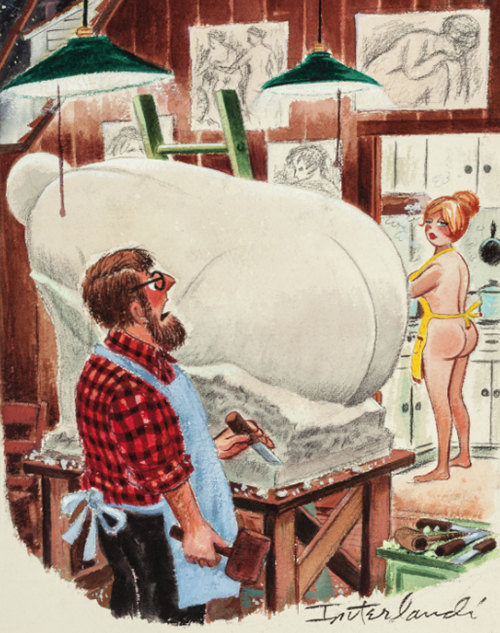

If secretarial work was a mainstay, the dream job for many young women was that of the model, which was not a new career path for women--the artists of earlier centuries had their models but they also often were expected to be prostitutes and typically ended their lives in destitution, used up and abused, if they hadn't the fortune to become a mistress to men in the upper class. With the super models of mid-twentieth century fashion photography, modeling had become not only acceptable but held out the promise of adventure and entry into glamorous society. Even in small towns, modeling schools introduced girls to runway modeling in local fashion shows, and prepped them for beauty contests. The Barbizon School of Modeling advertised in magazines marketed to teen girls. It was entirely sensible that a young woman would hope to be a model when she was taught from the cradle her looks and body were her primary assets, her investment in her future, while her intellect discounted as inferior, a great majority of careers were closed to her as she was considered incapable by virtue of her sex. Though a young woman understood she shouldn't be vain, and the selfless life was promoted with the example of Florence Nightingale heroes held out to her in school (not to mention nuns, if one was Roman Catholic), a woman's value as intrinsically linked to her desirability as a sex object was inescapable, as well her in-general value as a person. If Barbi could plead that a "meaningful" life was to be found in modeling, it was because a model was not just selling commodities, her world was interpreted as having access to all that was sold as providing a means to love and self-acceptance. "If I had this then my life would be perfect" involved not only the object but all that was associated with it, and how much better to be the model who not only helped invite that desire, but may be the Helen whose face launched a thousand ships.

But, again, we shouldn't forget that modeling was a career, and that women were sold a very few career options as being available to them.

A brief note about Barbi's attire in this scene. She seems to associate checks with "job", as she was wearing a checked shirt with a solid skirt at her secretarial job, and with her visit to the modeling agency she wears a red checked skirt and a solid color shirt. The photo spread in the Viva magazine we'd seen her looking at during the credits may also be associated with her attire as that involved the fantasy of a picnic and photo shoot on a large red-checked cloth.

On the advice that she needs a new look, Barbi visits Sherman of Hollywood (Sherman happens to be the original town name of what became West Hollywood) which she had seen advertised outside the Gladstone Modeling Agency. Sherman's is a home beauty salon done in bold red, navy blue and white, his kitchen a trustworthy sunny yellow, and Barbi appears to immediately feel comfortable, perhaps also because Sherman is obviously gay. Barbi takes a seat before a painting of a mouth with a lipstick before it, which may remind of Barbi applying lipstick before her vanity mirror and her satisfaction in doing so, as if she has each time taken on a new lease on life. Just as the stylist begins to cut her hair, a neighbor, Reeves, arrives asking for a cup of sugar. Sherman reads Reeves as gay, and so might the viewer, but Reeves, who has much the same hairstyle as Rick, flirts with Barbi, complimentary of her appearance, and she is flattered and a little flustered with the attention.

Reeves, as he sits and watches Barbi's hair being styled, absurdly eats the sugar in the cup, sticking his moist fingers in the sugar so the tips are coated with it and sucking the sugar off with increasingly sensual excitement.

Both Barbi and Sherman, captivated, become excited as well. But Barbi, when her hair is done, puts the brakes on and says it's time for her to go, which Sherman isn't having. His plan is to seduce Reeves, and his best bet is through Barbi. So he convinces her to stay a little while longer and have a shake to take the edge off the heat. What Barbi doesn't know is that the shakes contain a liberal dosage of "Magic Dust". As she and Reeves talk, she now makes it clear that she's married, and he reacts as if she's led him on. Sherman says that all women are like that, doing anything to get a ring on their finger, then playing around. Barbi should take offense but she instead laughs, the drug already having begun to affect her. She passes out and Reeves carries her to the bedroom, undresses her and presumably has sex with her, or attempts to, and is left unsatisfied. Sherman then seduces him in the same bed as the unconscious Barbi. When she wakes up, befuddled, finding the two men next to her, asleep in one another's arms, it's unclear if she understands what has happened, other than being aware she is only in her underwear.

Unsettled, left with presumably a disquieting hole in her life so that she's unable to make full sense of her experience, Barbi returns home, where we get our first good look at her dining room. The kitchen, as well the living room, are fairly rigorously co-ordinated with the exception of bold green flowered curtains and a few other touches. The dining room is less so, verging on chaotic. The carpet is tan and the walls are an aqua blue. An orange tablecloth matches up with the orange floral print of the chairs, the orange flowers, and a floral painting that is predominately orange, but the window is dressed in green drapes over white lace sheers, and a purple, brown, and green modern abstract painting further disjoints the scene. On the dining room table, beside an orange lace doily, she finds a note from Rick.

Barbi -- Am very sick. Have gone to the hospital --

Barbi retires to her bath, then to what we now realize is her private inner sanctum of the home she shares with Rick. The room that is her own.

In that room is the pink vanity where she daily examines herself in the mirror as she applies her face and considers what will give her life meaning. There are even gold sconces with pink candles on the wall to either side of the vanity. This is undoubtedly Barbi's sacred space.

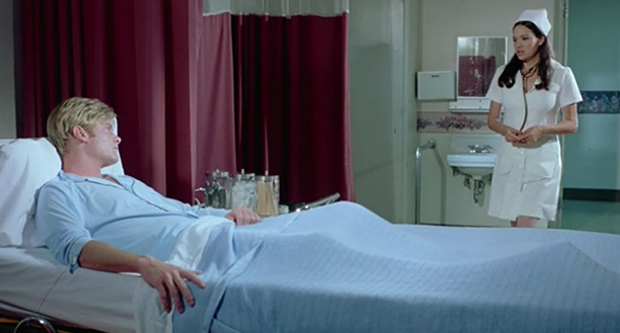

We then see Barbi in the bedroom she shares with Rick, dressing in a nurse's outfit.

Whatever she has planned, she needs a fair amount of preparatory wine to cement her resolution.

And she had a very bad night.

Another career for a woman was that of a nurse. From 1930 to 1970, in a space of 40 years, only 14,000 women graduated from medical school as doctors, so in the 1960s and early 1970s she couldn't yet be a doctor as the doctor role was for men. As the nurse, she was viewed as the secretary to the boss. The helpmate. The wife of the medical world. And, as with a secretarial career, going into nursing was also thought of as a means for women to meet marriageable male doctors, one of several reasons so many soap operas initially relied on hospital storylines as a mainstay.

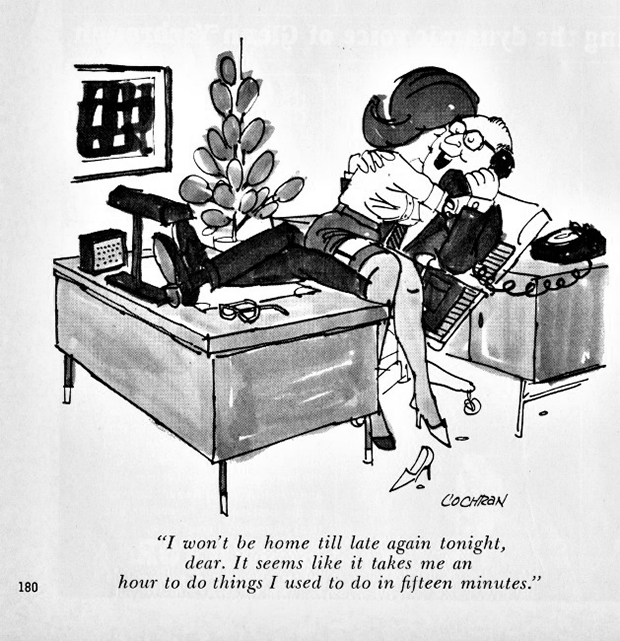

The doctor had career authority, whereas the nurse fell into the same madonna/whore complex that routinely, in whatever she did, divided women as selfless or predatory yet always subservient to men's needs. Teenage girls might be encouraged to be Candy Stripers, who volunteered at hospitals, and thus be introduced to the selflessness of the nurse. But as the flip side of the selfless Madonna is the whore, the nurse was a favorite naughty sexual partner in risque cartoons.

Barbi understands that as a wife she must also be the nurse, her husband's caregiver, and dresses for the role. At the hospital, she learns that Rick, upset over her not having come home the previous night, "worked himself into a state of hysteria...had a seizure which led to a high fever, followed by pneumonia." This is pretty much a classic mid-20th century, afternoon soap opera illness with only a smidgen of hyperbole. The doctor more than implies Barbi is at fault, but she leaps in and accepts blame before he can get the words fully out of his mouth.

Both the doctor and Rick are a little surprised and perplexed by Barbi's nurse costume, the film itself unwilling to accept the absurdity--but Barbi is oblivious and not at all the butt end of a joke. This is serious business for her.

Barbi was drugged and molested--perhaps raped--the previous night, but this doesn't matter. She accepts Rick's illness as entirely her fault. She doesn't even tell Rick where she was as she accepts what happened to her as being all her own fault, promising not to be bad anymore. She's going to nurse Rick back to health, doing everything he wants her to do. Which he is happy to hear. Barbi's payment is Rick telling her that she is good to him.

A woman who was raped, molested, or harassed, was blamed by simple virtue of her sex, and also by choices she'd made. What was she wearing? Lacy underwear? A short skirt? (And yet she couldn't wear trousers as they were masculine.) What was she doing in the wrong place at the wrong time? How had she provoked the situation? Why hadn't she fought to the death? Barbi, without her husband's approval, had sought a job as a model and gone to have her hair done. Her acting autonomously and wanting some adventure in her life has made her a bad girl. Barbi understands she is at fault for being in the wrong place where she was drugged (if she realizes she was drugged) and abused. Even worse, Barbi had been initially attracted to the man who molested her, and asked for his help before passing out. Even in 2007, the exaggerated sexual arousal during the absurd sugar-eating scene risked having Barbi judged as partly to blame for her assault, even though she attempts to leave and tells Reeves she's married. Of course it makes no difference whether Barbi was married or not, it is inconsequential, no woman is free game to be assaulted, just as Barbi's attraction to Reeves doesn't factor. Biller not only taps into the misogyny of the 1970s, but as it is in the present. The viewer may not even register how Biller has scripted the episode so that Barbi is first seen as complicit through her exaggerated heavy breathing in response to Reeves eating the sugar (the scene tempered by this absurdity), then is further condemned by her only being excused as victimized because she attempted to leave and revealed she was married. The ridiculousness of this seems too much to write, but these are little reflexive responses of sexism that people can have that they don't even consider, and may only appreciate how grotesque they are if they imagine Barbi being interrogated on a witness stand. Were you attracted to him? Were you sexually excited? Did you tell him you were married? If she answered yes to the first two questions, and no to the third, would Reeves have been found guilty in certain eras, certain places, with certain juries? Barbi, as her own judge and jury, passes sentence on herself and determines she was the one who was bad.

Biller now approaches how men did things, while the woman's role was to watch men doing things. As Rick and Mark play tennis, Barbi and Sheila stand to the side watching. They also hold rackets, so may also play, but their conversation spells out their role. Sheila remarks she loves watching men play tennis--so we do have her taking pleasure from it, but the statement is an in to realizing that the role of the woman is to watch. Barbi comments that Rick loves tennis and that from now on everything is for him, and Sheila shrugs, either out of incredulity of Barbi's wholly acquiescent announcement, or some bafflement as she has never considered her own relationship to being the woman who watches, but she doesn't question what Barbi has said.

Barbi, who has promised to give all her support and attention to Rick, presumably might likely feel compelled to never be in competition with him. Even in the 1970s, women were advised to not be too smart, and to let the man win, so his ego would be preserved, the woman having to take care to not cause a man to feel emasculated. Cradling a drink, she watches as Rick plays pool. Sheila, on the other hand, holds both a pool stick and a drink, so she does participate, which may be part of her role as the friend who is more worldly than Barbi. Pool was a man's game, and if she played well at all she would have some cache as being the woman who could play pool, but she wouldn't be expected to play pool seriously, either as a hobby or professionally, and she too would be expected to stand back by not playing her best. Though we have here a different situation, perhaps a party in someone's home, or a clubhouse, the mid-century America pool hall wasn't considered an acceptable environment for women, and they might not even have been admitted. In 1976, when the Women's Professional Billiard Association was founded, women were still not permitted to wear trousers in competition--their femininity had to be confirmed and culturally protected by the rule that they wear either skirts or culottes, despite the problems this would cause in negotiating a pool table.

With the Viva title, because of Viva Las Vegas, though I don't believe there's any relationship between the two films, I stil would have been disappointed if Biller hadn't included a car racing scene, and now, in this section about how women watched men doing things, Biller positions Barbi with binoculars to be the watcher of her man at play on the race course.

The Indianapolis 500 didn't even allow reporters in the pit area until 1971. The first woman to attempt to qualify to race there didn't occur until 1976, and didn't qualify until 1977. The racing of cars was a decidedly masculine sport even though it depended upon skill rather than brute strength. With tennis and other sports that depended in part or fully on strength, people could excuse women as not being able to compete in the same leagues as men, thus women's sports associations which weren't taken as seriously as men's and didn't receive the financial support, they weren't considered fully representative of the sport whereas an association that excluded women didn't have to be called a man's association, it was simply dignified as representing everyone.

Women watched. Watching was not only their place, but their duty. For instance, women were the cheerleaders, and even then they might have a male leading the squad.

There's a curious little bit where after Rick finishes on the course and gets out of the car he pulls out his cigarettes and looks up at Barbi.

He purposefully-accidentally drops his cigarettes.

He picks them back up, lights one, Barbi realizes he's expecting her to go down from the bleachers to him, which she does, and he throws his cigarettes away as she approaches.

They kiss.

We'll return to this later.

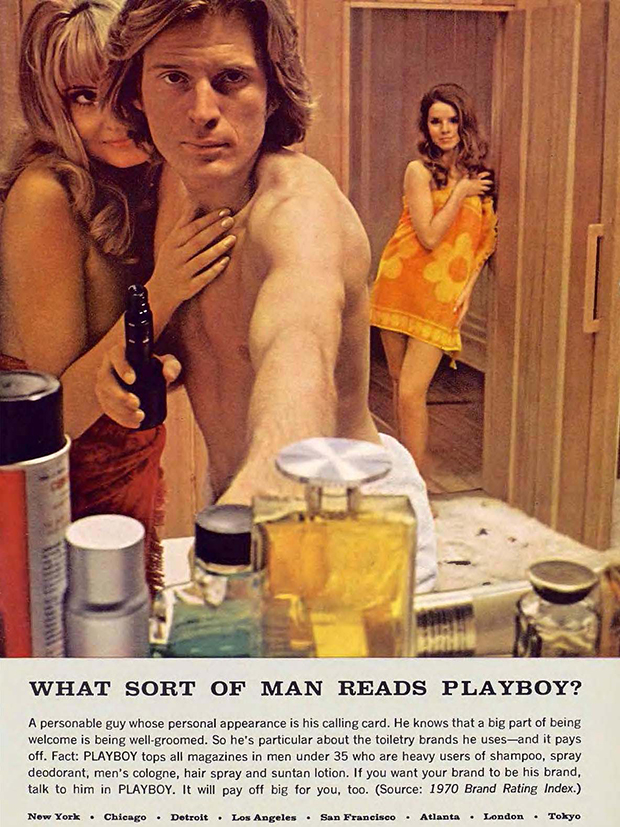

During the billiards scene, an older woman, holding a Playboy magazine, asks, "What sort of man reads Playboy?" A man takes out a card and hands it to her in response, replying, "A personable guy whose personal appearance is his calling card." Another man approaches and adds, "He knows that a big part of being welcome is being well-groomed."

Though the Playboy shown is from August, 1971, the dialogue refers back to the July 1971 issue observed in the scene were we first meet Sheila and Mark, and the below page that was in the July 1971 issue.

Biller highlights, without the viewer's knowing the source of the dialogue, the marketing aspect of Playboy, its platform the largest in the business for men under 35 in respect of toiletries.

Such as cologne. English Leather.

Copy for the "What Sort of Man Reads Playboy" ad in a 1966 issue related that Playboy leaded all magazines in percentage of households purchasing a new TV in the last 12 months. Refer back to Rick talking about how he wanted to get a new television.

Copy for another "What Sort of Man Reads Playboy" ad in a 1958 issue related that a larger percentage of Playboy families drank and served alcohol than those receiving any other magazine, nearly 70% of those homes consumers of whiskey, gin, rum or vodka. 1965 copy related that readers of Playboy purchased double the national average of movie tickets. Refer back to Sheila and Mark's 2 liter jug of Dewar's and brandishing it for the camera as they spoke about going to the movies.

Copy for a 1962 "What Sort of Man Reads Playboy" ad stated that over 75% of Playboy readers had one or more record players, the highest figure of all the men's magazines surveyed, that nearly 15% had two or more record players, and 11% "amplified their enjoyment with purchases of new record=playing equipment during the last 12 months. Refer back to Rick purchasing a TEAC.

1966 copy in another issue stated over 22% of the readers were members of country clubs, over 31% played tennis, over 42% played golf, and over 56% boated or took part in other water sports.

Playboy vigorously marketed lifestyle in conjunction with the sexual revolution. The men who read it had disposable income and were big consumers, influenced by Playboy's ads. Biller highlights this consumer aspect throughout Viva. Playboy wasn't just about the nudes, and the articles, it was about being a successful vehicle for advertisers.

One can look upon the nudes as being nothing but bait.

Note the man in the "What Sort of Man Reads Playboy" photo has one woman clinging adoringly to his shoulder while another woman waits for her turn in the background. Playboy sold itself as progressive and intellectual and a natural advocate for women's rights and their ability to enjoy sexual freedom along with men. But in actuality?

As Nathan J. Robinson wrote for Current Affairs:

The feminist criticism of Playboy has always been obviously correct. Hefner literally reduced women to little bunnies who existed entirely to suck his penis. Of course, there’s plenty of mention in the obituaries of Hefner’s “highbrow” aspirations. In his words “We enjoy mixing up cocktails and an hors d’oeuvre or two, putting a little mood music on the phonograph and inviting in a female acquaintance for a quiet discussion on Picasso, Nietzsche, jazz, sex.” But it was always clear that the intellectual side of Playboy was strictly for men: he refused to discuss politics or literature with any of his girlfriends. They were there for him to have joyless unprotected sex with whenever he pleased.

Hefner’s Playboy was committed to destroying the idea that women were people. As the Times quotes, Hefner demanded his writers go after feminism in the magazine’s pages:

“These chicks are our natural enemy. What I want is a devastating piece that takes the militant feminists apart. They are unalterably opposed to the romantic boy-girl society that Playboy promotes.”

That “romantic boy-girl society” was the “dream” Hefner frequently said he lived. It was little more than the dream of tyrannizing over women while wearing a bathrobe.

The world of Playboy was a profoundly sad one. In photos, Hefner never looks particularly happy, and he was a recluse who didn’t even seem to enjoy the copious amounts of sex he had. (“There was zero intimacy involved… No kissing, nothing.”) Hefner’s fantasy lifestyle was inhuman in every way. It was sex as something mechanical and lifeless, something one did because it was the thing that made you a Playboy, rather than because of true passion. That’s the dark secret about Hefner: he wasn’t even a hedonist. A hedonist pursues pleasure. Hefner didn’t even care about pleasure. He cared about the taming and conquest of women.

There’s an important critique of libertarian morality to the Hefner story, too. Hefner was an advocate for freedom from all kinds of government restraint, a champion of the First Amendment and abortion rights (as every obituary has reminded us repeatedly). He was a “passionate libertarian.” Hefner also believed he was changing American morality, saying: “What it really comes down to is an attempt to establish what has been called a new morality… really think that’s what this thing called the ‘American sexual revolution’ is really all about.” (This is taken from the NYT’s charming compilation of Hefner’s “Most Memorable Interview Moments.”) Here we see exactly what happens when “freedom” is taken to be a moral philosophy in itself. Like many libertarians, Hefner wanted to be free, but he wanted to be free from government tyranny only so he could exercise a kind of unaccountable private tyranny. As with libertarianism always, “freedom to be a dick” seems to be the goal. He wanted to establish a “new morality” that would simply let him do as he pleased to women, without any ethical constraints. “Liberty,” while essential, is meaningless unless it is also coupled with a set of standards for how people should actually behave toward one another.

I know someone who in the late 70s briefly worked developing film at a newspaper. One of the several photographers employed had, for his kink, the habit of blowing up pictures of a glimpse of women's undies that he'd catch on different shoots. The majority were the costumed rears of cheerleaders revealed under their short skirts, but any assignment was fodder. I recollect the photo of a woman who had been in a car accident, which he'd blown-up, highlighting her underwear. He was proprietary, taping these on the wall in the coffee niche of the photographer's area, where he also placed copies of Hustler magazine he brought from home. He was a senior photographer, both in station and years, and no one was going to take him to task as they would have been fired. He "owned" the space. During a time when I was trying to get a start in film and photography, and was unsuccessfully looking for photographic work that would give me practical intern experience, in spaces that were entirely male because that's all that existed in my area (I was told I wouldn't make it), visiting at about the age of nineteen and seeing how professional newspaper photography was being predatorily misused was mind-boggling to me as I had this idea of journalistic photography as a profession that dealt with the mundane but also nobly labored to uncover societal injustices. Needless to say, there were no women in the department because it was broadly thought back then that women couldn't be photographers, and there was also the matter of simply not wanting to make room for women in aggressively male spaces that were sexist, the men not wanting to have to curb their behavior. What kind of man read Playboy? There would have been crossover between the Playboy reader and the Hustler reader, but Playboy sold a "progressive" lifestyle and a veneer of respectability, whereas Hustler was aggressively only about sex. Playboy aimed to make one feel that this was what a woman wanted in a man, that this was where male and female could co-operatively meet and get what they wanted from one another. But, as shown in the above quotes from articles, men were being granted freedom to use women in a sexual revolution that only gave the impression women were equals ahd had equal opportunity.

Barbi brings Rick breakfast and tells him his bags are packed for his business trip, including his skis, but she wonders how he'll have time to ski with all his business meetings. Rick blithely announces that's why he'll be away for a month, so that he'll be able to enjoy business and leisure. Barbi reminds him they had a trip of their own planned in two weeks, and he tells her if he doesn't ski now he won't be able to do so for another year. Barbi suggests that maybe she could come along then, but Rick adamantly tells her no, she'd only be bored. Barbi suggests that Rick is perhaps fooling around, and he scoffs. When Barbi says she's only disappointed, Rick blows up. He just needs to have some fun every once and a while, to go outdoors and express himself. He says she's being a ball and chain. Barbi tells him he can go away forever if he wants, and Rick replies he just might do that. He tells her she's really blown it, that before he wanted to come back and now he's not sure. He's going to need time to think. He'll call her when he's good and ready, and she may be just left waiting a long time.

Barbi was supposed to commit her life to seeing only to Rick's needs and interests, this was what Rick wanted, and still she fails with Rick because he decides she's always on his back and he needs time away from her for self-expression on the ski slopes.

Barbi calls Sheila to tell her of her misfortune. Sheila has the August 1971 issue of Playboy in hand. Perhaps she's just been reading Morton Hunt's piece in that issue on "The Future of Marriage". Marriage, Hunt had determined, was not in decline, but evolving, and for the better, shifting away from patriarchal monogamy into new forms. Divorce, he said, was a healthful adaptation, "enabling monogamy to survive in a time when patriarchal powers, privileges and marital systems have become unworkable." While this all sounds well and good, and Horton stated this likely meant in the future alternative families (gay and lesbian) which was then far outside cultural discourse and acceptability, Horton in an earlier piece had, according to Carrie Pitzulo's Bachelors and Bunnies: The Sexual Politics of Playboy, affirmed that "men rule the public domain; women, the private", that it was "only reasonable" men "should be the heads of families and their primary breadwinners, and that women, as the primary caregivers should accept 'a secondary part in the world of work and achievement in order to have a primary part in the world of love and the home.'"

So, what happens when, as with Barbi, having wholly accepted that as a primary caregiver she should devote herself to love and home, she is abandoned by the husband for whom she made the home?

As it turns out, Sheila has separated from Mark, who has moved out and in with his brother. She tells Barbi to put on a sexy outfit. They're going to exercise their new-found freedom. Shelia's choice? A see-through crochet dress. She determines Barbi's choice of attire isn't sexy enough and redoes it so that Barbi's breasts are completely revealed in a transparent blouse. When Barbi protests that they can't go out like this, Sheila protests that it's the 70s and they are liberated women, free in the city, and without husbands.

Is this what it meant to be liberated in the early 1970s? I would hazard that the pages of Playboy often enough gave that impression. In the same July 1971 issue as the interview with Cassavetes was also a Woody Allen feature, "I'll Put Your Name in Lights, Natividad Abascal", in which he boosted his newest film Bananas via his then girlfriend, model Natividad Abascal, who appeared in the film. Some photos show her lying nude on the beach, while a couple show her in a shawl wrapped around her pelvis as a barely-there skirt, and another shawl draped around her neck, its long fringe covering her breasts in the ineffective way that a beaded curtain covers a doorway. And she wears many strings as beads as well. Allen joked, "“Before Naty signed her movie contract, I told her about the sexual obligation that was a part of the job of any actress who worked with me...Aware of my position as a father figure on the set, I let her come to me with her problems as often as she wished. When she never showed up, I came to her with mine."

We will think back to when Barbi went to the Gladstone Modeling Agency and was ogled outside as "classy" (regardless of attire women then and now are continually subject to street harassment which they are told they should even appreciate). Now, Barbi is uncomfortable with the attention they attract, and so does Sheila even seem to be. Her adventure isn't going as planned. But then a madam spies them and, mistaking them as prostitutes, approaches Sheila and Barbi with the intention of getting them to work for her. In disbelief, she learns that they work as housewives. "Dressed like that?" Sheila responds that they want to have adventures. The madam asks what they want. Sheila's dream is to find a rich man who will buy her a fur coat and diamonds and isn't a cheapskate like her husband. As for Barbi? She wants to meet someone who is kind, sensitive and loving. Mrs. James tells them that she can arrange all that, and if they come up to her parlor they can discuss it.

Up in Mrs. James' parlor we've a costume change into chokers and nighties, as Biller dips back into her film A Visit from the Incubus for an illogical Victorian setting in 1972 America. To cement the point, she even leaves in view a dressmaker's dummy in a Victorian dress.

We're also treated to one of a number of purely lovely shots in the film, Sheila in sea-foam green and Barbi in pink seated on a flaming red couch against a pink background.

Mrs. James initially presents her business as being a single's agency whereby people can meet up casually, the man paying her a commission fee. But one can make a little money on the side as a call girl, she adds, dropping a cube of sugar in her tea, which should remind us of Reeves literally eating his cup of sugar.

Barbi is taken aback at the idea of being a sex worker, but Sheila is all in for it, saying she has always wanted to be one and that it sounds romantic. When Barbi wonders if it's morally wrong, Sheila explains it's part of the sexual revolution, taking advantage of one's newfound sexual freedom. Phrased that way, Barbi can accept it as a process of self-exploration concerning her sexuality. For her new job, her alternate identity, Sheila takes the name of Candy. Barbi takes the Italian word, "Viva", which means to live, because that's what she wants to do, to live, to be a new woman. In fact, she insists she will never be Barbi again.

"Viva" is connected both with the magazine Barbi had been reading as well as with a fascination she has with Italy. Appropriately, Biller's soundtrack is filled with clips from Piero Piccioni's soundtrack for Camille 2000, C'era Una Volta, and Il Medico Della Mutua. Many other pieces are used as well but I remark on these because of Piccinoi's featuring among the composers of Italian jazz scores who created distinctive, vividly emotional and all-encompassing music for such directors as Roberto Rosselini, Lina Wertmuller, Elio Petri, Frederico Fellini and Michelangelo Antonioni. Biller's choices, however, don't depend on being evocative of those films in such a way that would disrupt the world she has created.

Biller continues with the Victorian theme, costuming Viva and Candy in Victorian corsets. Viva and Candy's first client is Dr. Collins, and as they're expecting a doctor they're briefly taken aback when he arrives and he obviously is not. Instead, he's role playing, just as they also are using fake names. He boldly, excitedly calls them whores, tells them they look sick, fondles their breasts, then prostrates himself for the good spanking he deserves for assaulting them. The readiness with which Barbi and Sheila fall into being prostitutes is almost disconcerting, and one wonders does it fit the characterizations thus far constructed. The answer can't be simply in Barbi having changed her name to Viva and adopting a new persona. Instead, we should perhaps view it in comparison with Barbi's secretarial job, which was unrewarding and came along with sexual harassment. At least, here, she is playacting the boss, spanking the man, in control, she's protected by being in the company of a friend, which also normalizes the work, and both of them enjoy being handed the cash and feeling in control of their money. Everything is jovial and as Collins puts on his tie afterward he even has somewhat the aspect of an exaggeratedly comic character in a Norman Rockwell painting. And their boss is a friendly woman who has quickly won their trust, even promising to fulfill their desires--but we will eventually learn she is as willing as many other bosses to sacrifice her employees.

This is sex work as cleaned up and predominately playful as depicted in such films as The Owl and the Pussycat, featuring Barbara Streisand, and Irma La Douce, featuring Shirley MacLaine.

Rick, in the meanwhile, is angsting over his split with Barbi. As Viva and Candy play "whores" in a playful, idealized situation in which they don't have to deal with the burden of feelings, he is at the ski resort bar, turing away a blonde and brunette team who approach him, flatter him, and ask him to buy them drinks. He turns them down, as well another woman, and goes to call Barbi who is not at home. Viva is giving Mrs. James her cut for the night, and Mrs. James is promising to set Viva and Candy up with their dream men.

Candy's dream was for a millionaire who would give her riches Mark can't afford. The millionaire is an ancient man who prefers that she is an "older" woman at twenty-nine. They go to a restaurant where the hostess scathingly remarks that though Candy's fur coat does a lot for her, she's sure Candy has done a lot for it, but Candy permits herself to be only a little bothered--she has her "date" to entertain and must keep on a happy face, which seems to not be too hard for Candy as she is more than content when she has a fur and diamonds from Cartier. This is, for Candy, a fair and equitable exchange.

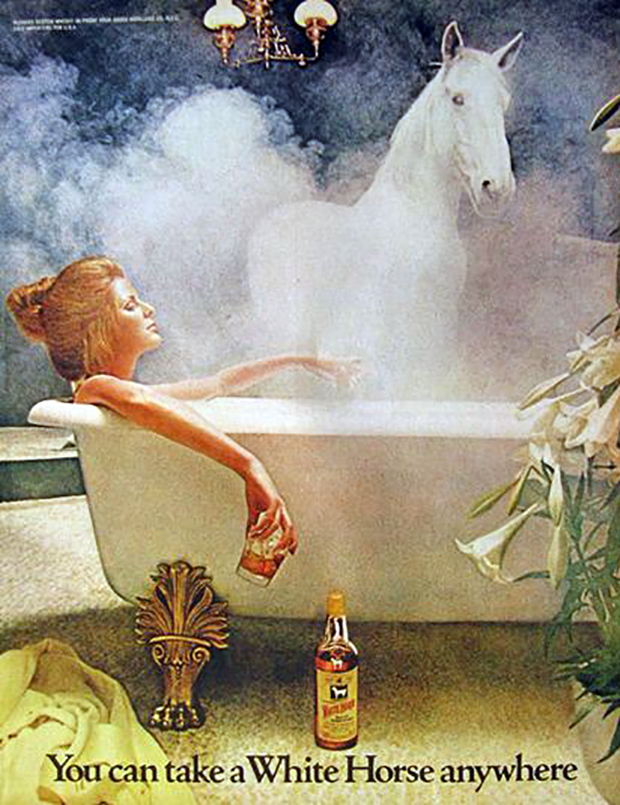

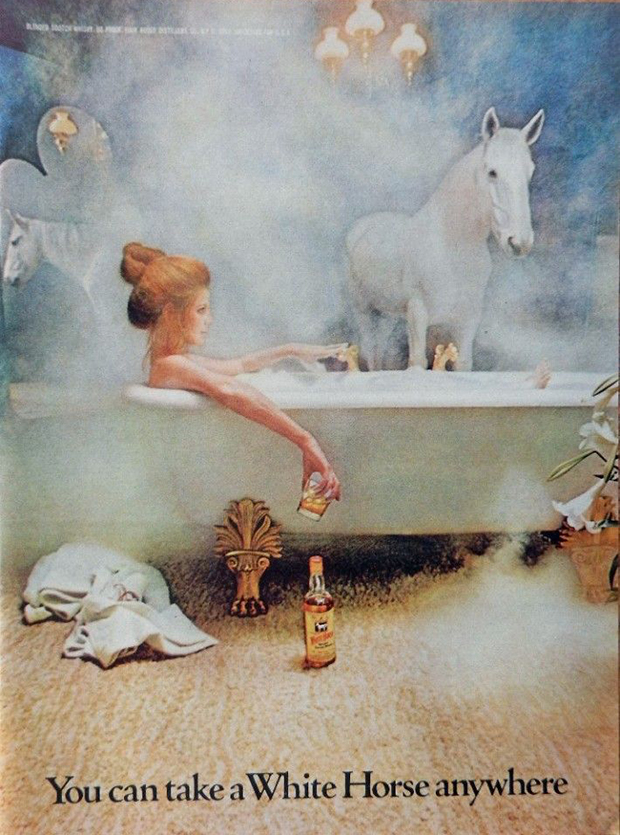

Candy has something else she has always wanted, and this seems to be where Candy's true dream comes in. She wants a white horse in the mist. Google "white horse in mist". This seems to be a thing, and I know nothing about it other than when I was a pre-teen I had friends who were crazy about horses, and the fact that sex and romance have often been depicted in film with carefree horse rides along beaches. The white horse is close in spirit to the wild unicorn that could only be captured by the pure-hearted virgin.

I'm going to take it for granted that Candy's musical number in the dream bath with its gold fixtures is expressing what she truly feels, and that a sexual relationship based on a man giving her gifts is just fine with her. This is her psychology. The romance for her is in the things that she receives, a luxurious lifestyle is her romantic fantasy in which she feels herself treated as a goddess. The man doesn't much enter the picture except as the provider. Biller's version of what would have been at one time called a "gold digger", though Candy is in it for the money, doesn't have the cynicism of many films. At this point it accepts Candy as she is.

In the bath, the white horse in the mist has been exchanged for a bottle of White Horse scotch. She pours herself a glass--not like an ad at all but the White Horse made prominent and reminding of the importance of associating lifestyle/fantasy + brands + sex in advertising and Playboy's content, not to mention how in most advertising the selling of a commodity involves the fantasy of how it will make one's life better.

The musical number in the bath with the White Horse scotch would seem to have been inspired by the below ad for White Horse that ran in Playboy. Though the lead copy line for these was, "You Can Take a White Horse Anywhere", other ads for White Horse stated that, "The Good Guys are Always on the White Horse."

In another version of the ad the horse is less immersed in steam and the woman's extended left hand is clearly resting on a hot water tap. I may be wrong, but I would think the initial ad had been of the woman with her hand on the tap. There is also a mirror to the left reflecting the horse. In the above version of the ad, the mirror is gone, the taps have been removed so her hand is nonsensically adrift in the air, and elements have been moved so her hand is poised in front of the horse. In the version without the taps, the horse certainly more dominates the scene and is more dream-like, almost aggressively so.

There are probably a number of people who appear as extras in different scenes in the film. If we go back up to Rick at the ski resort bar, we see next to him a man in a red jacket. I think this is the same man who Biller has chosen to sit in the booth behind Candy at the restaurant. Just a fun bit to notice.

Following the promise of a sincere man, Viva is sent to meet Elmer, and finds herself at the Healthy Valley Nudist Resort, the screen filled with male and female bodies of all sizes, none of them having the perfect form that usually is all that's permitted in film and advertising. Though her green and pink flowered dress is short, from the waist up Viva looks almost prim, the dress giving the appearance of a jumper over a long-sleeved green blouse with a pleated bodice and high Victorian lace neck decorated with a green velvet bow. And Viva is prim, to the extent that when she is told she needs to remove her clothing to be permitted on the grounds, she refuses, insisting she is only there to meet Elmer. After she's directed to where she might find Elmer, a man remarks, "Marcuse's Foundation is Freud's principle that our instincts are founded in the pleasure principle of Eros, or libidinal energy. Too often we sublimate this energy into a work impulse, which is what makes civilization possible." The statement would be just out of Barbi's hearing, but in a less succinct distillation of Marcuse's philosophy we may find some ideas that address Viva's life and journey. I shall resort to Wikipedia for some only slightly less succinct exposition.

Marcuse's analysis of capitalism derives partially from one of Karl Marx's main concepts: Objectification, which under capitalism becomes Alienation. Marx believed that capitalism was exploiting humans; that by producing objects of a certain character, laborers became alienated and this ultimately dehumanized them into functional objects themselves. Marcuse took this belief and expanded it. He argued that capitalism and industrialization pushed laborers so hard that they began to see themselves as extensions of the objects they were producing. At the beginning of One-Dimensional Man Marcuse writes, "The The people recognize themselves in their commodities; they find their soul in their automobile, hi-fi set, split-level home, kitchen equipment," meaning that under capitalism (in consumer society) humans become extensions of the commodities that they buy, thus making commodities extensions of people's minds and bodies. Affluent mass technological societies, he argues, are totally controlled and manipulated. In societies based upon mass production and mass distribution, the individual worker has become merely a consumer of its commodities and entire commodified way of life. Modern capitalism has created false needs and false consciousness geared to consumption of commodities: it locks one-dimensional man into the one-dimensional society which produced the need for people to recognize themselves in their commodities.

Rick is driven by business, which separates him from Viva. We already have seen how materialistic their lives are in Rick's pursuit of the best stereo system, wanting the new Camaro, working toward the goal of being able to eventually purchase the cabin and fishing boat that will provide relaxation, an escape from his job--and we realize that earlier discussions of these things were a set-up for addressing Marcuse. In Viva> we see individuals who recognizes themselves in the commodities that style their existence, seeking self-definition in them.

Viva finds Elmer, who is a guitarist, and is harangued by his friends for not feeling comfortable enough to remove her clothing. She's told clothing sets up arbitrary social codes, and is derided as uptight. Elmer, the guitar effectively clothing his genitals, tells everyone to live and let live and sings about love, how its good for you, me, trees, and all humanity. He takes her back to his place where, clothed now, he tells Viva how he wants to get to know all about her, and Viva confides in him about her fight with her husband and how she realized she could be having adventures rather than being the house wife. But though Elmer says he wants to pull out the real Viva, and loves her, his interest is sexual, and Viva insists that she wants to get to know him first. Elmer persists, and when she won't undress so he can see her body he becomes petulant. Using the paintings of the nudes on the walls to remind her of having sex with Rick, Viva gives in, and she and Elmer have sex on a veritable sea of crochet. Elmer's place is the crochet heart of the film.

In the morning, Viva tells Elmer that rather than hating herself for sleeping with him, she hates him. That's a step in the right direction.

She returns to the madam at the agency and complains that the sincere and natural man was too natural and focused on the physical.

Viva is sent to meet Clyde, an artist, who Mrs. James as assured her is just the man for her. Sherman of Hollywood's space was dominated on one side by bright red, and on the other by navy blue. Clyde's space dispenses with the blue for an ultra-bold statement of red and white. As with Elmer's, nudes bedeck the walls, as well as abstracts representing nudes. In case we might wonder what Clyde wants, he spells it out in a sign on his bar. SEX. There is no crochet in evidence.