TWIN PEAKS: THE RETURN

Go to Twin Peaks Table of Contents for a note on the analysis.

PART EIGHTEEN

TOC and Supplemental Posts | Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Part 8 | Part 9 | Part 10 | Part 11 | Part 12 | Part 13 | Part 14 | Part 15 | Part 16 | Part 17 | Part 18 | Films Home

LINKS TO SECTIONS OF THE ANALYSIS ON THIS PAGE:

HOME

FIND LAURA

The curtain call

4-3-0

RICHARD AND LINDA

COFFEE AT JUDY's

#6 TELEPHONE POLE

THE LONG DRIVE

WHAT YEAR IS IT?

NOTE: The structure of the analysis is simplified as we move into the last few chapters, blending commentary with description of the shots in a looser manner.

HOME

It's the last Part of Twin Peaks: The Return, and it seems there is so much to wrap up, so many mysteries unresolved, and we should realize by now, with the manner in which some of those questions have been answered, frequently birthing only new mysteries, that Lynch's only formula is to obliterate routine formula. Which is why you like him. We've no way of anticipating what will happen. This is art. We can only roll with it and accept the Lynch-Frost vision as it is as long as we feel it is authentic and not disingenuous.

In Part 17, after Mr. C had been shot by Lucy, and Freddie had defeated Bob, Cooper had slipped the jade ring onto Mr. C's hand, but we had not seen him returned to the Red Room, we had only seen Mr. C's body disappear in a haze of white smoke, then a shot in the Red Room had revealed the jade ring dropping to the floor, sounding with the distinctive, singing resonance of the metallic ringing tone we've come to associate with the ring. Part 18 opens with Mr. C flaming in the transformation chair, black smoke pouring from him. He looks like he might be doomed, forever, to walk with fire, as it were.

Through the darkness of future past, the magician longs to see. One chants out between two worlds "Fire walk with me".

But then the chair is empty and Gerard places upon it strands of Cooper's hair with the "another" golden seed Cooper had asked him to make when he'd woken in the hospital.

GERARD: Electricity. (He stands back.)

DOUGIE (appearing and looking about happily): Where am I?

We leave the Red Room and zoom in on Janey's door. From inside, then, we hear the doorbell ring.

JANEY: Just a second.

Janey opens the door to find Dougie. Sonny Jim comes running and they all embrace.

JANEY: Dougie!

SONNY JIM: Dad? Dad!

DOUGIE: Home!

A cheery, "Where am I?" This is not the same fairly normal Dougie who was transported from Las Vegas to the transformation chair when Mr. C escaped being returned to the Black Lodge. This is not the Dougie-Cooper who took his place, the classic fool whose behavior becomes as a koan inviting enlightenment in those who try to understand the riddle of his actions and words. This is not the preternaturally capable FBI agent who took the fool's place and promised Janey E. he would be returning. He is a new configuration, whose seeming immediate tendency is for wide-open awe and joy. He smiles upon formation, when confronted with the unknown. He doesn't return to Janey E. as a blank slate, he knows his home in Las Vegas, but whether or not his full history as Cooper has been returned to him, and accompanies him home, is left up to the viewer to ponder, the intimation being that he will not have whole access to Cooper's knowlege and experience. A number of the viewers dearly wanted some kind of good end for Dougie, who was and was not Cooper. Back in Part 13, with all the dreams coming true for Dougie's family, when Tchaikovsky's "Dance of the Swans" played as Sonny Jim played on his new swing set beyond a golden arch, there'd been the fear, as Janey told Dougie that she loved him, that all this would collapse, that it wasn't real. Whether or not it is "real" (peculiar to demand of a fictional story) no longer much matters. Whatever alternative world this is, Janey and Sonny Jim have been reunited with Dougie, and one of the versions of Cooper has a wonderful life.

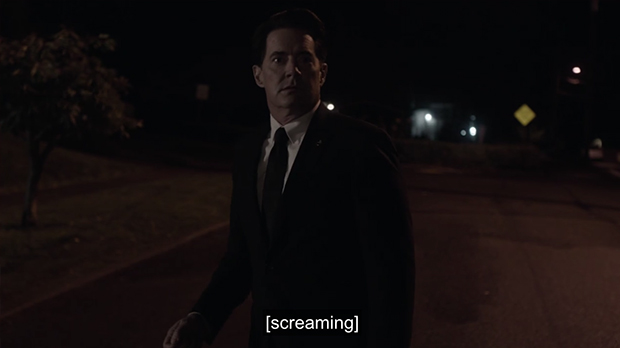

From the reunited Dougie, Sonny Jim and Janey, we then jump back to the end of Part 17, when Cooper had found Laura Palmer on the night of her murder, his plan being to change the future and save her. Recognizing him as a man she had dreamed about (we don't know if she speaks of the man who told her not to accept the jade ring, or the man to whom she whispered a secret) she had the trust to take his hand, though he wouldn't tell her who he was, and when she asked where they were going he had answered, "We're going home". Then, as they had walked, the "future-past" had changed, her plastic-wrapped corpse disappearing from the river's shore the following morning. Laura's immediate future no longer was a life cut short by her father and BOB. But as their clasped hands had passed an angled tree, Laura had disappeared. Shocked, hearing a scratching sound, Cooper had turned to hear a whooshing, then Laura screaming.

This time, he hears a clicking sound following, and we find him again in the Red Room.

In Part 16, near a slot machine showing a sphinx and a scarab (a rebirth symbol), we had the promise of Cooper returning to Janey and Sonny Jim in tulpa form, Cooper telling them that he would be returning home to them--and there may have been a sense of disappointment to this promise for the viewer, that Janey and Sonny Jim were not geting the "real deal", that the Dougie-Cooper who returned wouldn't be the one who was making the promise, that instead the father and partner that would walk through the red door would be manufactured. We might have felt a sense of their being cheated, but then we have no idea what the "real deal" concerning Janey and Sonny Jim actually is, how "real" they are. We only know that Cooper has had the opportunity to experience a family through them, but is now leaving it and sending to them a substitute as he continues on his quest. In Part 18, after all that has happened, with all the uncertainties, the viewer may simply be grateful that there is a version of Cooper that experiences a happy ending. But Cooper has relegated this family experience to a tulpa so that he may continue on his personal odyssey.

Lynch links together the "home" that Cooper sends his tulpa to enjoy with his telling Laura, "We're going home." Which requests that we examine what is "home". Cooper doesn't say to Laura, "I'm taking you home", he instead says, "We're going home." He self-identifies, this is personal, though he has never experienced Laura's world before her death.

But to what has he thought he's returning her? Life with Janey E. and Sonny Jim, the viewer anticipates as one full of love and hopeful promise. In Laura's case, for anyone who's been abused, their immediate response would be to cringe at this idea of Laura's home being even a remotely desirable space for her. She hasn't been safe there for years. Perhaps she was never safe there. Why would Laura want to go home? Why wouldn't she scream in horror at the prospect of returning home? Not that we're given the feeling that this is why she screams, for she follows him as one in thrall, not contemplating her future, only being in the moment, led by Cooper, trusting him. Instead, the feeling is that she is kidnapped by forces beyond their control, as in the Red Room, in Part 2, when she was spirited away, screaming, after revealing to Cooper she was alive yet dead, then whispering to him their secret when he had asked her, "When can I go?"

Return to the top of the page.

FIND LAURA

THE CURTAIN CALL

In Part 2, after Margaret had called Hawk and they had spoken about how something was happening that night, for which reason Hawk was out walking in the forest at Glastonbury Grove, then cut to Gerard with Cooper in the Red Room. Gerard had asked, Is it future or is it past?, then had said, Someone is here, and, Gerard disappearing, Laura had appeared in the chair next to his. She'd told Cooper he could go out now, then their conversation had partly recreated one in the original series in which Cooper had been artificially aged. She'd asked Cooper if he recognized her, had spoken of her arms sometimes bending back, then saying she was dead, yet alive, she had shown him the light behind her face. She had then kissed him and whispered in his ear, after which there was a violent whooshing sound and she was spirited violently away, screaming. A white horse had appeared in the distance, then Gerard had appeared again, and, again he had asked Cooper, Is it future or is it past? After this, Cooper was taken to see the evolution of the arm as the tree, which asked Cooper if he remembered his doppelganger. The show had returned to Buckhorn and Mr. C killing Darya, then had gone back to the Red Room in which the tree had said, 2-5-3. Time and time again, had spoken of BOB, then told Cooper to go now. Cooper came upon Leland who told him to find Laura, and one had to wonder why, when Laura was dead. Why should he find a dead woman? After this, Mr. C fighting being returned to the Black Lodge, rather than switching places with Mr. C in his car, Cooper had transitioned to New York, then to a lavender-purple world, and finally through an outlet into the life of Dougie.

This time, things occur a little differently.

Gerard had asked his question.

GERARD: Is it future, or is it past?

Gerard had then disappeared and, hearing a soft whooshing sound, Cooper looked at the chair where Laura had originally appeared. She does not appear, however, and the viewer may wonder if it is because she wasn't murdered. The viewer has expected her to appear, but does Cooper? Does he remember that this is a repeated event?

Because Gerard had previously said to Cooper, Someone is here, we should likely think back to Part 17 and Jeffries having said to Cooper, when he was sending him to where he would find Judy, There may be someone...did you ask me this? In response, Gerard had shaken his head both yes and no, which may suggest actually that, if we go by Gerard's response, this had happened before and both responses were appropriate.

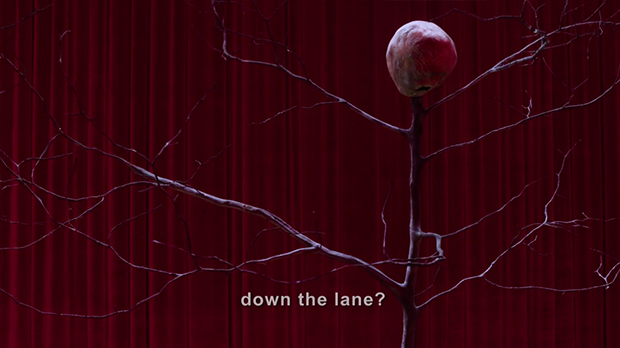

Gerard reappears and Cooper follows him to the Arm. Rather than The Arm asking if Cooper remembers his doppelganger, and telling him the doppel must go in for him to be able to go out, The Arm instead repeats a line Audrey had said in Part 13, when her husband had so bizarrely threatened to end her story, breaking the fourth wall to remind us Audrey is only a fiction and Audrey's "life" depends upon art.

THE ARM: I am the arm and I sound like this. (Electric static.) Is it the story of the little girl who lived down the lane? Is it?

In response to this, Cooper's expression is near identical the aspect of the transparent "double" that, in Part 17, had layered over much of the activity after BOB's defeat, beginning when Cooper's attention had been drawn to Naido, finally disappearing when Cooper had gone to the basement of the lodge and entered the room from which a ringing sound emanated.

Now we find Cooper again in his chair and Laura leaning down to his ear to whisper into it what has become less her secret than their secret. But was she not there when we earlier expected her to be there--because she hadn't died? Why is she in the Red Room now, whispering a secret that originally (at least supposedly) had to do with her father murdering her? Then she screams violently, as she had in Part 2, and is swept away. Cooper stares up in amazement. Then he looks across the room and we appear to see him enter. Instead, Cooper is "exiting" and as he exits he comes across Leland.

LELAND: Find Laura.

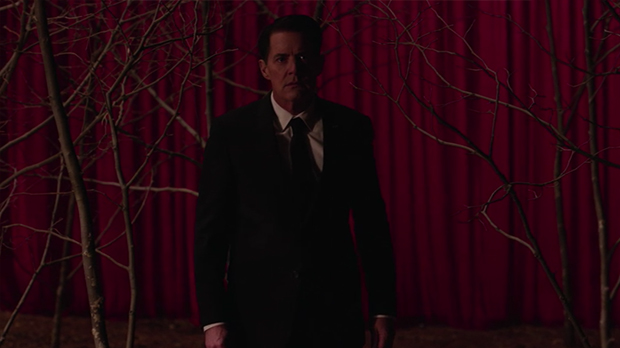

There is no problem with Cooper exiting the Red Room any longer. As he walks down its curtained hall, he reaches out, waving the fingers of his right hand, a curtain flutters, he passes through it and out into Glastonbury Grove.

Improbably, Diane awaits him there.

DIANE: Is it you? Is it really you?

COOPER: Yes. It's really me, Diane. Is it really you?

DIANE: Yes.

This is the curtain call, and we're in completely uncharted territory. What is Diane doing there? How had she known to be there? How does this link to the night when Hawk went to the forest, expecting something to happen? Diane and Cooper confront each other as meeting now the authentic self of the other. We are still bewildered by this relationship between Diane and Cooper, which is somewhat explained in Frost's book, but is an explanation that has little to do with what is happening here. The explanation in the Frost book is to provide some kind of history that purports to make sense of what happens between the lines but doesn't. The passion with which Diane and Cooper exhibited in Part 17 had nothing to do with the first two seasons of Twin Peaks. It had nothing to do with the woman we never saw in those seasons, who was only a tape recorder.

The red curtain fades.

WHO'S AFRAID OF VIRGINIA WOOLF AND THE LITTLE GIRL AT THE END OF THE LANE

I watched again, The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane, considering the reference possibly made to it in Part 13, when Charlie threatened to end Audrey's story and she had replied, "What story is that, Charlie? Is that the story of the little girl who lived down the lane?" I had read the book as well, and was ruminating not only on relevance to the series, but also how coping with anti-semitism and American brand white supremacy is a fundamental and critical part of the novel that seems to have become lost in the 1976 film adaptation, how the child is set up to be in peril due anti-semitism, and coping mechanisms that have gone awry. In the meanwhile, I watched Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf again, a film I've seen a number of times, and had considered previously that Audrey's character in The Return, and her relationship with Charlie, had some similarity to the fraught relationship of Martha and George. But this time, watching the film, it hit me that Martha and George's fictitious son was called "Sonny Jim", and that when George decides to end Sonny Jim's story, as it were, it's by the agent of "crazy Billy" delivering a telegram.

If one is unfamiliar with Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf, Martha is the middle-aged daughter of the president of a New England college, and George is her middle-aged professor spouse. Martha is loud, bold, audacious, and George is the seeming passive component of the pair, abused by Martha's assaults on his manhood. They drink. A lot. After one of Martha's father's faculty parties, Martha invites a new, young professor, and his wife, over to their home to continue drinking and partying. Nick and Honey. Over the course of the night there are stories, given as fact, that are eventually revealed to be fiction.

Martha is an intelligent mid-twentieth century woman whose live has been structured by sexism and the status quo so that her role is to be the wife of a professor who it's supposed will eventually take her father's place at the college. She would have been expected to have children with George, but apparently they've been unable to have a child. Instead, we find Martha and George have conjured a secret fantasy child. This particular night, Martha moves that fantasy child into their social life, so he is no longer secret, and George decides this violation signals the necessity of the child being killed off. An author who has not attempted to be published because of his controlling father-in-law, we also learn George had years before written a book in which a boy accidentally kills his mother by gun, then later accidentally causes the death of his father in a car crash, after which he is hospitalized and never speaks again. George initially tells Nick this story as a matter of fact rather than the subject of his novel. He tells Nick he knew the person to whom this happened. A question emerges of intentionality, that these were not accidents, when Martha reveals that this was the plot of George's novel, and that he'd said it was his own experience when his father-in-law described the fiction as mocking him and demanded he not publish it. Whether or not these events were part of George's experience is left unanswered, but we get perhaps a better grasp on the reality of the pair when, at evening's end, George "kills" their child by telling a story of Billy having delivered a telegram stating their son, whose birthday was the next day, had died in the same type of car accident that had killed the father in the novel. In the book, the boy, driving the car, had swerved to avoid hitting a porcupine and had wrecked the car, and the father, a passenger, had been killed. Many years later, Sonny Jim, swerving to avoid hitting a porcupine, wrecks his car and dies.

Martha claims that George has no right to kill their child, the fantasy. He is not god. But, as an author of Sonny Jim's existence, he is as a god, determining the life of the character. The problem is that Martha has a share in this, being also the creator of Sonny Jim, but she has succumbed to the fantasy and revealed it to others.

There's even a trip to a roadhouse in Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf. George and Martha end up at a roadhouse with Nick and Honey, where Honey does her interpretive dance ("I dance like the wind") until she's policed by her husband and drunkenly, petulantly, furiously plants herself at a table, after which Nick and Martha seduce one another as they dance and Martha spills the story about George's novel, prompting George to choke her. "Violence!" Honey exclaims. And it is a terrifyingly violent scene, the horror of which is nearly lost in the prickliness of their relationship coming close to dangerously normalizing the abuse for the viewer.

The roadhouse has been a liminal place of music and violence throughout The Return, and one could compare the Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf play/film with Audrey's trip to the roadhouse with Charlie where, as she dances, a man attacks another, yelling, "Monique! That's my wife, asshole!" Which is when, fleeing the violence of two men fighting over a woman, she entreats Charlie to get her out of there.

Sonny Jim, of course, is the name of Dougie and Janey E's son, which has caused some perplexity among viewers, that he is "Sonny Jim" though his father is not a Jim. The development of the story of Dougie's family has a too-good-to-be-true aspect that is, at times, even alarming, the fear arising that Sonny Jim is at risk, perhaps Janey-E as well, and that they will eventually be dissolved because their impossible good luck reveals them to be impossible characters. But the viewer is invested in them and this pains, so one is relieved when, in Part 16, Cooper-Dougie assures Sonny Jim that he is indeed his father and that he will return. And he does. The family hugs and their story line ends with a preservation of Home.

Sonny Jim, I think, very possibly can be found in the imaginary child in Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf, which in the hands of Edward Albee has a God/Madonna/Christ aspect to it as well, the son sacrificed by the god-father as the mother wails. A counterpart story is echoed with Honey having a sensitive stomach and running to the bathroom to vomit with every crisis. As it turns out, she and Nick had married because she believed she was pregnant, but Nick's belief is it was a "hysterical" pregnancy as it then simply disappeared. As it turns out, it seems Honey, terrified of having children, had an abortion. What is most salient to Twin Peaks is the dream child who becomes too real and George kills with a car accident when Virginia betrays the fantasy to Nick and Honey.

Audrey, who terrorizes Charlie, much in the same way that Virginia terrorizes George, lives in an obviously impossible situation, stuck, seemingly unable to leave her house, and is trying to find "Billy", who she believes is in danger, who she loves, who we never see but seems to be mentioned in the world of the Roadhouse and is thus real there. Audrey is threatened by Charlie with his ending her story (which reveals his control over her)--to which she responds, what story is that, the story of the little girl who lived down the lane? This is a line repeated by The Arm before Cooper successfully leaves the Red Room in Part 18.

Indeed, Audrey's story does end, in response to the violence that awakens her from the dream of her impossible dance, which she'd initially performed when enthralled by Cooper. A fight between two men over a woman so terrifies Audrey that she flees to Charlie and pleads with him to get her out of the roadhouse. But she doesn't disappear. Instead, Audrey wakes up staring at herself in a mirror in what may be a blank slate state. There is no story around her. Her room is all white and she's dressed in white. She and her mirror are all that's left, providing a peculiar feeling of circularity with the pilot episode of Twin Peaks when we see Josie sitting before her mirror just before Laura's body is found on the shore. and, again, in Part 17, when we see Josie sitting before her mirror after Laura's body vanishes from the shore. Then we see Sarah Palmer repeatedly stabbing Laura's homecoming queen photo, because her daughter will not die, she will not die, the picture and the glass protecting it repeatedly reforming.

Richard, Audrey's violent psycho of a son with Mr. C, had already been annihilated at the beginning of Part 16. I've the feeling that when Cooper-Dougie sticks the fork in the electric outlet is an event concurrent with Richard sparking out on the hill and Audrey waking to the bright white room. Sonny Jim is preserved. The nightmare of psycho Richard ends.

In Part 13, when Audrey's husband had threatened her with cutting her story short, she had asked what story was it, the little girl who lived down the lane? For which reason, I'll return to the 1976 movie, which I've already briefly discussed in Part 13.

What of the little girl who lives down the lane? I can't imagine it's a reference to the 1976 film that was a Jodie Foster vehicle. I am more reminded of Grace Zabriskie showing up at Laura Dern's doorstep in Inland Empire, announcing herself as a "new neighbor" who lives "just down the street", and then telling her of the little boy who saw the world when he opened the door, but as he passed through the doorway he caused a reflection, and evil was born. And then another tale of a little girl who went out to play and was lost in the marketplace, as if half born, but not through the marketplace after all but the alley behind. She'd said, "But it isn't something you remember. Forgetfulness, it happens to us all." She can't remember if it's today, two days from now or yesterday. "If today was tomorrow, you wouldn't even remember that you owed on an unpaid bill. Actions do have consequences. And yet there is magic. If it was tomorrow you'd be sitting over there."

I have since rethought whether or not we need to also consider the movie, The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane. The story involves a girl, Rynn Jacobs, just turned thirteen, who is living on her own as her father had, from when she was three years of age, raised her apart from an emotionally and physically abusive mother. According to the girl, when her poet father learned he was terminally ill, he had set the daughter up so that she would financially be able to survive on her own, explained to her that she was different and must do whatever it takes to survive apart from others, had kissed her goodbye, then had disappeared down the lane and supposedly committed suicide by drowning himself in the ocean. We are inclined to think of only the mother as abusive, though the father was abusive, certainly, for he had done nothing to socialize the girl, he had put her in a position of being removed from society, he had told her society wouldn't understand her and she must make herself very small so as not to be noticed. He had put her in a postion of being necessarily secretive, and, moreover, had instructed her to give her mother a certain sedative if she should ever appear. He had not told the girl it would kill her mother, which it did. One could consider that everything the father did never was in the interest of protecting the girl but instead was an intentional setting up of her to murder her mother. First, she had to hide her father's suicide, which separated her further from society, and then she had to hide how she had, however without premeditation, murdered her mother. At that point, for all intents and purposes, and in that era, the girl would have been considered by society beyond redemption. It's unlikely the abuse of her, by her father, would have been understood, though she was only thirteen. Certainly, when her suspicious landlady, Cora Hallet, finds her mother's body, though the landlady's subsequent death is accidental (the trap door to the basement, in which the mother's body is hidden, hits her on the head, killing her), she would likely be considered accountable if only through covering that death up.

It should be noted that in the book the girl intentionally kills her mother, by poison, and that when the landlady discovers the body she intentionally kills her by gassing her. The girl is softened up for the film, but her guilt in the novel is qualified by her father's grooming her to live an absolutely isolated life. She's an intelligent girl, but immature, and in a sense she's carrying out her father's directive. Also, she is Jewish and has no family to help her as her father's family is dead. Did they die in The Holocaust? This isn't stated, but that the girl expresses fear of a gas heater in the novel, presumably because a neighbor in London committed suicide by gas, and her choice to kill the landlady is by gassing her in the basement, raises this grim possibility. When the girl kills the landlady, who is a virulent anti-semite, she does so believing she is saving herself, that she has no other choice, and the gas seems not an expression of revenge but the author making an overt connection to The Holocaust being a cause of this isolation and survival by any means. Regardless, the girl has been emotionally abused by her father who, if he carries the trauma of The Holocaust, has transferred it onto the girl in such a way that she has no chance at all, he has raised her to be alone and fearful of others. What she learns, over the course of the novel, as well as in the film, is that she can't live as her father directed her. She needs others. She can't survive on her own.

She learns she can't survive without others when she falls in love with Mario, an older boy.

He's a magician complete with cape, top hat and cane (the cane disguises his lameness, caused by polio) who befriends her, wins her trust, and witnesses how Frank Hallett (played by Charlie Sheen), the landlady's pedophile son, is threatening her, Frank bullying him as well. He is a witness to Frank killing her hamster, Gordon (a white rat in the book). Rynn reveals to Mario all that has happened--her mother's death, her father's suicide--and he scarcely flinches, understanding her victimization. He comes down with pneumonia after helping her bury the bodies of her mother and the landlady, is hospitalized, and Rynn's despair at her solitude increases, compounded with the threatened loss of Mario. With the hospitalization of the boy, Frank shows back up, discovers what she's done, and tries to blackmail her into being his sex slave. The movie ends with her successfully, intentionally poisoning him.

Rynn and Mario's relationship develops into a romance and they sleep together. At one point, he masquerades as the girl's father in order to make it appear that the girl is not living alone. Then when Mario is hospitalized, the predator surprises the girl by emerging from her basement dressed as the magician, so at first she thinks it's the boy and is excited and relieved, but then realizes it's Frank. Rynn had just gone through an evening of realizing how she can't live by herself, she needs others, she loves Mario, and as Frank presents to her his plans for their future it is again one of isolation, just as had been planned by her father. And I do wonder at this, if the girl had not been only emotionally abused by her father, but sexually as well. In the novel, after Mario and Rynn sleep together, which she initiates, Mario cries and withdraws, which may only be due his apparent failure on the initial attempt, but there are peculiar undertones. Rynn, just turned thirteen, is unabashed. Both incidents are preceded by Mario's wearing Rynn's father's robe...and perhaps I'm reading too much into all this, but the author seems to be signalling something, but what?

Without a doubt, we are being referred to the scene I've already discussed in Inland Empire, all of Lynch's work woven together. But I think we have also an allusion to the multiple realities of Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf, in which Sonny Jim's story is ended by George, this connected initially with Audrey, the threat of ending her story, which she compares to The Little Girl who Lives Down the Lane, changed to "the little girl who lived down the lane". It's even spoken of by The Arm. The question is why. Why compare Audrey's story to that fiction?

Mario is a magician and we have the magician(s) in Twin Peaks. Frank is a pedophile predator, comparing with Laura's situation. The girl, in isolation, has others believe her father is still alive, when instead he is dead. The magician makes him appear to be alive. Frank also adopts the magician's costume so Rynn is initially fooled and thinks he's Mario.

I also briefly consider that the girl was played in the movie by Jodie Foster, and that I find, in a Slate article on the name Jodie, alternative spellings include, "Jody, Jodi, Jodie, Jodee, Jodey, Joedee, Joedey, Joedi, Joedie, Joedey, Jodea, Jodiha, Johdea, Johdee, Johdi, Johdey, Jowde, Jowdey, Jowdi, Jowdie. Its origins are Hebrew. Jody is a diminutive of Judith, which means, simply, woman of Judea or Jewish woman.'' Some of these spellings come too close to the Jouday that had eventually become Judy. Besides which, Judy is itself a diminutive of Judith.

If I return to Audrey and focus so much on her here, it's because Audrey is the single primary character who questions her reality, though it's discounted as "existentialism 101" when she does so. She's the one who says she doesn't feel like herself, that she feels like she is others, that she can't trust her own identity. She's the one who finally screams, "Get me out of here!" and wakes up. As we progress, we will realize how even Cooper finally is working on a kind of automatic pilot, not questioning his surroundings, no matter how bizarre, not questioning why he does what he does. But Audrey wakes and is faced with herself. Alone. With nothing around to give the audience a sense of place, and we sense that she too is in the same predicament. Just who am I? What has been happening? Where am I? It is Audrey who wakes after looking for the missing Billy who she dreamed was in trouble. But who is the individual who has been missing throughout The Return? Audrey. Her mother and father exist in the town of Twin Peaks. Her brother exists in the town of Twin Peaks. Her son exists. Her uncle exists. But no one talks about Audrey, except for, briefly, Doc Hayward, remembering that he saw Cooper exiting the intensive care unit where was the comatose Audrey. Frost's book fills in that she had her child, had broken completely with her father and not reunited, had her own beauty salon, eventually married her accountant, did some heavy drinking and ended up in a private care facility. But Frost's story doesn't feel like Audrey. She's missing from that as well, and it doesn't begin to account for her name not even being mentioned by Ben when he speaks to Sheriff Frank Truman about Richard in Part 12, the same episode in which Audrey finally first appears with Charlie. Obviously, that Audrey wasn't spoken about was supposed to heighten tension and keep the viewer wondering just where is she, what's happened to her, was she perhaps even dead? But, dead or alive, in normal conversation her existence wouldn't have completely erased. And then even after we finally see her, she isn't referred to except for Richard's telling Mr. C she had his (Dale's) picture. If she isn't spoken of even after we see her, Frost's story is meaningless. The viewer is intended to not know what has happened to Audrey and to ever question her peculiar circumstances and the fact she is missing.

4-3-0

In a 1963 automobile, Diane and Cooper travel down a desert road, coming upon a stretch of great electrical transmission towers.

DIANE: You sure you want to do this? You don't know what it's gonna be like once we...

COOPER: I know that. We're at that point now. I can feel it. (Referring to the odometer.) Look. Almost exactly 430 miles. (They pull over.) Exactly 430 miles.

DIANE: Just think about it Cooper.

He gets out of the car and walks toward the pylons. We hear electric static. He looks at his watch.

In Part 1, Cooper had been told to remember 4-3-0, Richard and Linda, and two birds with one stone. The viewer has been alert throughout the episodes looking for these things.

Cooper used to wonder, to question, but now he knows. Again, we are in uncharted territory. Cooper has somehow come to understand what 4-3-0 meant and that it was a place.

I return to Part 11 in which we see the nude body of Ruth arranged in a manner that reminds of Duchamp's Etant Donnes, my thinking of this because of the address where Duchamp created the art, at least in part, being #403.

"Peep Show", an article by Morgan Meis on the art work, states of it,

When you walk into the room where “Étant donnés” is housed, all you see is a wooden door on the opposite wall. You have to walk up to the door and examine it. That’s when you notice the two little holes at roughly eye level. When you look through the holes you see the scene in the park, the naked woman, etc. It is impossible to “look around.” The placement of the holes prevents this. You will never see the face of the woman in the grass. You will never understand anything more about her situation than what you see through those little holes.

If we consider again that etant donne is "the given knowledge with which you begin to play a game or the initial situation a detective finds himself in", that inability to peer around speaks to not only the detective's knowledge that is initially blind to all but the portion of the scene presented, we can of course relate this to Cooper's situation as a detective, but even more so w the audience relative the many open-ended questions Lynch's The Return leaves us. Whether or not 4-3-0 has anything to do with the Duchamp work, the comparison still is relevant. Also, The Return opened with the mystery of the discovery of Ruth's head upon the body of Major Briggs, her body not discovered until Part 11 in which Gordon (Lynch) was himself threatened with being pulled into the vortex. As with so many other mysteries, the rational behind anything regarding the storyline of Ruth and Bill and Gordon is never approached--how Ruth is murdered but Bill is initially not, how and why Gordon's body is placed in Ruth's bed with her head and Ruth's body is left in the small field. We eventually almost forget that Ruth was even a part of the story, by the time we reach the end, and yet she is present as she is thematically linked with Naido/Diane/Linda.

COOPER (returning to the car): This is the place, all right. Kiss me. Once we cross, it could all be different.

They kiss.

DIANE:

Let's go.

Cooper releases the brake on the car, slowly rolling it forward past the transmission tower.

And then they are suddenly driving, silent, through the dark of night. They say nothing to one another, nor do they look at one another.

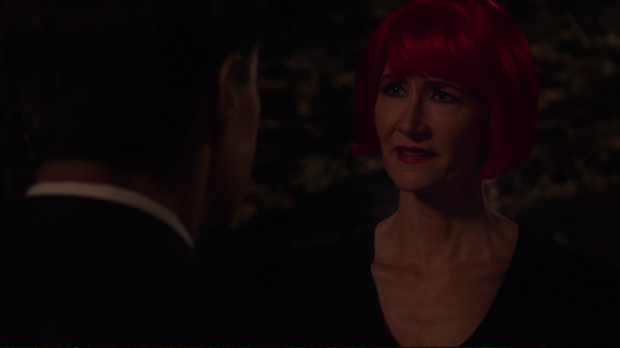

They come to a motel. Cooper parks. He doesn't glance at Diane as he climbs out of the car and walks to the office, Diane watching from the car. He goes in, and Diane sees herself step from behind a brick column. She and her doppelganger stare at one another.

Cut to Cooper exiting the office and going to stand before room #7, before which they are parked. Diane gets out of the car and joins him.

At this point, we can't even be sure which Diane is with Cooper, the one who was in the car or the one who was glimpsed standing near the office. We may be intended to parse the doppelganger's appearance as signalling that they have done this before, which appears to be the explanation for certain repetitions in The Return that are out of joint with each other. Perhaps, in another version of their stopping at the hotel, Diane had not stayed in the car, she had gotten out and stood near the motel's office waiting for Cooper.

They enter the motel room and Diane cuts on the light.

COOPER: Turn off the light.

DIANE (turning off the light): What do we do now?

COOPER: You come over here to me.

Diane does as Cooper tells her. He says, Diane, and they kiss. They make love to the "My Prayer" song by The Platters that had played in Part 8 when several people in a small town in New Mexico had fainted into a sound sleep, including a young girl who had been walked home by a boy who said he was no longer seeing a girl named Mary and asked to kiss her. A DJ and secretary at a radio station had been murdered, and a shadow man, who looked like Lincoln, had intoned over the radio, T"his is the water, and this is the well. Drink full and descend. The horse is the white of the eyes and dark within."

Diane keeps her hands over Cooper's face, as if she can't tolerate seeing, as they have sex, the same face that had raped her, that of Mr. C.

The picture of the desert on the wall reminds of the New Mexico desert observed in Part 8.

When the twilight is gone and no songbirds are singing

When the twilight is gone you come into my heart

And here in my heart you will stay while I pray

My prayer is to linger with you

At the end of the day in a dream that's divine

My prayer is a rapture in blue

With the world far away and your lips close to mine

Tonight while our hearts are aglow

Oh tell me the words that I'm longing to know

My prayer and the answer you give

May they still be the same for as long as we live

That you'll always be there at the end of my prayer

Following up on the little that is explored in Frost's work on the magician/rocket scientist Jack Parsons, his acquaintanceship with Aleister Crowley, the Working of Babalon, and Parson's attempt to produce, with Marjorie Cameron, Crowley's "Moonchild", now would be the place to discuss this and Frost's fictional additions that bring Parsons into the extended world of Twin Peaks. Diane's bright red hair may even remind many of Marjorie Cameron, a woman who Parsons imagined to be as Babalon, the Scarlet Woman. I just wanted to note all this, and that I've read a good bit on these individuals, and have read Crowley's Moonchild book, and I understand why many would interpret this scene as a form of sex magic--but to what end? And how much attention should be given this rather than approaching the magic in other ways? In the Crowley book, the woman used to produce the Moonchild is an example of a person who seems to give consent but is in reality used and abused. The sex Diane has with Cooper may be "consensual" but she was raped by Cooper's double and throughout she is pained and tormented, despite her consent, covering Cooper's face, while he is more or less present only as a physical body. This magical Diane, who manifested out of the vessel of the limbo vessel of Naido, had entreated Cooper not to make this "crossing", which has taken them into this darkest of nights, to this mysterious motel. But Cooper has given up everything but his quest, and here converts Diane into a part of the process.that musically connects them to that desert night, in 1956, when, listening to the Woodsman's message broadcast within this song, a waitress at POP's diner had fallen into an unnatural deep sleep, as had a mechanic (as if variations on Norma and Ed), and Sarah as well, after having been coaxed into her first kiss, the frog-bug then entering her mouth as she slept.

Return to the top of the page.

RICHARD AND LINDA

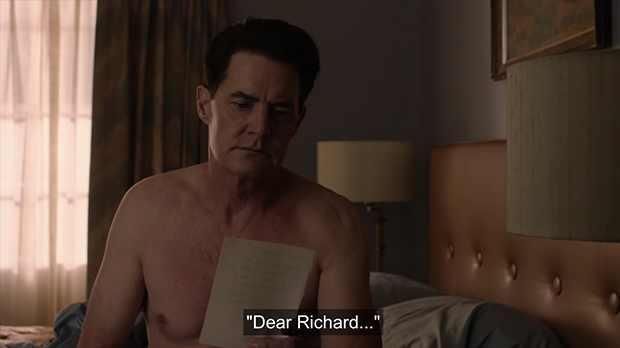

In the morning, Cooper wakes expecting to fine Diane with him, but the bed looks like he is the only one to have slept in it. He calls out a couple of times, Diane? Diane? He then sees on the bedside table a note that has been left for him.

COOPER: "Dear Richard" (He stops reading for a moment, looking puzzled.) Richard? (He continues.) "When you read this, I'll be gone. Please don't try to find me. I don't recognize you anymore. Whatever it was we had together is over. Linda."" (Finished, he reflects a moment longer.) Richard. Linda.

When Cooper exits the motel room, he pauses, expecting to see the car in front of the door, but then sees it across the lot. This is a different car than the one he arrived in, just as this is a different motel, but he recognizes the car as his own.

He crosses to the car and opens its door. He stops and stares back at the motel, as if to puzzle out what is happening. As he exits the parking lot we see a lamp and tree that remind of The Arm, a rephrasing of it.

Cooper is puzzled by his situation. Something isn't right. But he doesn't remember how this is so.

We had just been taken back to Part 1 and the Fire Man telling Cooper to remember 4-3-0, Richard and Linda, and two birds with one stone. We've had 4-3-0, and now we have had Richard and Linda. But who are Richard and Linda?

Was he supposed to remember Richard, the son of Mr. C and Audrey? The only Linda encountered in the episodes was a veteran living at the trailer park who had finally gotten her wheel chair. 430 is finally revealed in this part as a specific place where there will be a transition as Cooper continues his quest to find Laura, as well as Judy. Now Richard and Linda are revealed to be Cooper himself and seemingly Diane in an alternate reality? Linda says she doesn't recognize him any longer, just as Audrey had, in Part 15, found Charlie to be a different person, she felt she was seeing him for the first time. When Cooper had emerged from the Black Lodge/ Red Room into the forest, Diane had asked if it was really him and he had asked if it was really her. He had called her by name, Diane. Before the transition, she had called him by name. He had also called her Diane at the motel, before they had sex, so we can be confident this change has occurred at some point after that.

This is yet another variation of Cooper and the quality of his self-assuredness has changed. He doesn't appear to lack confidence, but he does seem not to question, almost as if he has one driving raison d'etre and his focus is so much on it that there's no room left for observing what is happening. Diane was there. Now she is gone. Continue moving forward. It's as though, as he moves along, he forgets about everything but returning Laura Palmer to Washington. He hasn't the enthusiasm or the joy of the old Cooper. He is not Dougie-Cooper, but he seems only partly conscious.

On the day that Phillip Jeffries had appeared at the Philadelphia home bureau, Cooper had dipped into his office and noted how something had changed, then realized Diane had moved the clock. In this way she would challenge his powers of observation. That ability to note differences and consider them is gone. He had said, when crossing over, that things could be different, but he can no longer assess and ponder the peculiar.

On a purely practical level, Diane must leave the story at this point. Cooper must continue alone in his odyssey. He can't be with Diane any further than this. He can't be with Diane when he meets up with Laura Palmer/Carrie Page. Diane couldn't have ridden in the car with them back to Twin Peaks. With the way that Cooper now is, for these scenes to work, Diane couldn't have been with him, he must journey alone.

Return to the top of the page.

COFFEE AT JUDY'S

Cooper drives the same 2003 model of Lincoln Car as Mr. C had wrecked, and in which Gordon had ridden through South Dakota to the penitentiary to meet Mr. C the first time. As Cooper heads down the road, we see he is in Odessa, Texas. The car has Texas plates. The viewer is going to rightfully wonder how Cooper has suddenly ended up in Texas.

There is also a small town by the name of Odessa in the semi-arid, central region of Washington State, in Lincoln County.

He sees a restaurant, Eat at Judy's, before a shipping container holding area. A train whistle blows. After a moment's thoughtful pause, he turns into the parking lot.

Inside the restaurant there are only two tables of customers--an older man and woman at a table, and three men in cowboy hats at a booth. A waitress asks the elder couple if they would like coffee. She pours some for the man but the woman declines. Cooper enters and takes a seat at a booth in the expansive room that feels too large for a diner, that hasn't the intimacy and the humanity we associate with the Double R. As the server approaches the table, the atmosphere already feels toxic.

KRISTI (the server approaches with a menu and coffee pot): Coffee?

COOPER (as she pours him coffee): Is there another waitress that works here?

KRISTI: Yeah. It's her day off. Actually, it's her third day off.

This is not the Cooper we knew in the first two seasons. He would never behave in this manner. There is nothing of his love of coffee, his easy and convivial rapport with individuals.

The waitress approaches the cowboys. She can be heard asking if they want coffee. They manhandle her, and Cooper notices. In Part 5, Richard had abused a woman, Charlotte, at the roadhouse when she asked for a light, and no one had stepped in to stop it--or, no one had been able to effectively stop it. One of Charlotte's friends had called out for Richard to leave her alone but he'd only laughed at her and continued. The same happens here. Cooper calls out for them to leave the server alone, but this time the abuse is stopped.

KRISTI: More coffee? (Protesting their pulling on her.) Stop it.

Stop it! Stop. Stop!

COOPER: Leave her alone.

The cowboys stand and approach Cooper.

COWBOY IN TAN SHIRT:

What the fuck you doing?

COOPER: What?

COWBOY IN TAN SHIRT (pulling a gun on him): Get the fuck out of that booth.

Cooper slams the man's hand, holding the gun, down to the table and kicks him in the groin. Another cowboy goes to pull his gun and Cooper shoots his foot.

Oh, fuck! Oh, shit! Oh.

Oh, shit. The elder couple stares on, amazed, but they don't move. The third cowboy freezes.

COOPER (to the third cowboy): Put your gun on the ground.

COWBOY IN DARK SHIRT:

I don't have a gun.

COOPER:

Put your gun on the ground.

The cowboy complies. Cooper tells him to sit down on the ground. He collects two guns, the elder couple querying one another who he is. On his guard, he goes behind the counter.

COOPER (to Kristi): Write the address on a piece of paper.

KRISTI:

What?

COOPER: Write the address of the other waitress on a piece of paper.

We hear bubbling oil and see a fryer basin behind him. He takes out of the vat a basket of french fries.

COOPER: Where does this go?

KRISTI: What?

COOPER: Where do you hang this?

KRISTI: Above, in the slot.

Cooper hangs the basket of french fries up and drops three guns in the oil.

COOPER (to the cook): I don't know if the oil's hot enough to set off those bullets, but I'd move away. (To Kristi.)

Did you write down her address for me?

KRISTI: Yeah, but, um...

COOPER: It's okay. I'm with the FBI.

Cooper's voice sounds flat, dream-like. He exits, leaving the cowboys to wonder, What the fuck just happened?

What just happened? Good question. It echos the puzzlement of Frank, Bobby and Hawk at Jack Rabbit's Palace. Odessa might bring to mind Homer's Odyssey but Odessa, Texas has as a symbol (so says Wikipedia) the Jack rabbit and for a long while had a Jack rabbit rodeo. Are we intended to think back to Jack Rabbit Palace? Despite the majority of viewers not being aware of Odessa's connection to Jack Rabbits?

There's a certain discomfort with Judy being now associated with a restaurant beside a RR yard, considering the Double R (railroad) diner back in Twin Peaks where we've seen Cooper so joyfully sip his coffee in a way that he doesn't here. But there had already been the RR associated with the diner in Part 2 at which Mr. C eats with Darya, Ray, and the mute Jack, Mr. C stressing he needed nothing, he instead wanted. One may also be reminded of how, in The Return, the roadhouse is not only a stage for music but violence, most notably Richard's attack on the woman who asked for a light.

The Twin Peaks viewer has wondered for years who Judy might be--first referred to by Jeffries who adamantly said Judy wouldn't be talked about "at all". Who/what is Judy, which Gordon eventually reveals is an ancient malevolent force, which Mr. C himself seems clueless about when he asks Jeffries if Judy wants something from him and demands to know who Judy is, Jeffries telling him he's already met Judy and then giving him the coordinates. We know Mr. C received two sets of coordinates that took him to the hill where Richard was killed, and another set that took him to the place near

Jack Rabbit's Palace, where was a golden-colored oily well, which would seem a counterpart of the oily well at the Glastonbury entrance to the Red Room. At Judy's, Cooper deals with the oil of a fryer and I think this is a reframing of the oily wells only now in a realistic rather than fantastical situation.

The Frost elaboration in his The Final Dossier is that Judy (Jouday) was the same as a Sumerian demon, and that if the female and male forms had an earthly child the result would be to hasten the end of the world. I could very well be wrong, but this strikes me as Frost attempting to explain in his own way what Lynch would describe in another, and that the Frost explanation would be considered to be more satisfying to the audience as it gives them something concrete. However, what comes with the end times in the Christian religion but the idea of the Judgment Day, the Day of Wrath, Dies Irae, and I have considered that Frost and Lynch may be using the town of Odessa not only to communicate a long voyage (such as Cooper's) but this Day of Wrath, of Judgment, as some believe that Odysseus is associated with "odussomai", which is to be wrathful, to feel anger, rage, hate. Suffering by implication is also suggested.

How did Cooper end up at Eat at Judy's? Was this his destination? Was the find an accident? We have the sense of both occurring--as if he leaves the motel with a determination of blindly going somewhere and it's when he sees the restaurant that he realizes what his destination was while also not consciously comprehending he did not know. But he is certainly there knowing what he is looking for unless he would not ask for the other waitress--the one who has been out for three days, the term of Good Friday to Easter death and rebirth.

A very interesting find, on Steven Miller's Twin Peaks Blog, is the revelation that the scene of Cooper waking up at the motel was apparently filmed at the restaurant. His night with Diane was shot at a real motel location, then the room was rebuilt in the middle of the restaurant, which was said to have been closed for three days for this shoot, the same amount of time the other waitress had been absent.

Return to the top of the page.

THE THIRD APPEARANCE OF THE #6 TELEPHONE POLE

Cooper drives to the address and as he pulls up in front he looks, disbelieving, at the deteriorating house and its wreck of a yard. A bird flies overhead, as had happened with the establishing shots of Dougie's home in Las Vegas.

He notes, before the house, a telephone pole nearby marked "6" and the transformer above. This is the same pole that was at the Fat Trout Trailer Park where was the trailer of Teresa Banks, who was murdered, and where Chet Desmond disappeared after finding the green ring atop a pile of earth beneath the Chalfont trailer. The utility pole was seen at the intersection where Richard Horne hit and killed a young boy. Andy was shown the utility pole during his vision in the company of the Fireman.

He parks, and as he approaches the front door we see, among other things, a noose in the yard.

He knocks on the door and inside we see a woman who looks like Laura Palmer approach the door.

CARRIE: Who is it?

COOPER: FBI

Without hesitation, she flings open the door, as if she had been expecting the FBI.

CARRIE:

Did you find him?

COOPER: Laura.

CARRIE:

You didn't find him?

COOPER: Laura.

CARRIE:

You got the wrong house, mister.

COOPER:

You're saying you're not Laura Palmer?

CARRIE: Laura who? No, I'm not her.

Now...

COOPER: What's your name?

CARRIE (after a moment): Carrie Page.

COOPER:

Carrie Page?

CARRIE: That's right.

Now, I got to go, so...

COOPER: Wait.

So the name Laura Palmer means nothing to you?

CARRIE: Look. I don't know what you want, but I'm not her.

COOPER:

Your father's name was Leland.

CARRIE:

Okay?

COOPER:

Your mother's name is Sarah.

CARRIE (hesitantly, bewildered):

S-Sarah?

COOPER: Yes, Sarah.

CARRIE:

What's going on?

COOPER: It's difficult to explain. As strange as it sounds, I think you're a girl named Laura Palmer. I want to take you to your mother's home, your home at one time.

It's very important.

CARRIE: Um...Listen, normally, somebody like you comes around, and I tell him to fuck off. This door would be slammed in their face. Right now, I got to get out of Dodge anyway. It's a long story. So riding with the FBI just might save my ass. Where we going?

COOPER: Twin Peaks, Washington.

CARRIE: DC?

COOPER: No, state. Washington State.

CARRIE:

It's a long way?

COOPER: It's a ways away.

CARRIE:

Let me get my things. Come on in.

Carrie didn't shy from opening the door when she heard it was FBI. She flung it open as if she was expecting someone, and perhaps it was FBI. She even demanded, "Did you find him?" A person is missing and she was expecting news on the missing person. Or this person is perhaps why she needs to get "out of Dodge", they are dangerous to her. But Cooper doesn't ask about this. He doesn't ask about who might be missing, who she hoping had been found. His focus is narrow, only on finding Laura, and his only response initially is, "Laura."

Carrie doesn't even seem to know that a Washington State exists. She must ask if it's a long way away. This would seem impossible for an adult to not know about Washington State.

These above things are even more curious than Laura Palmer suddenly entering the story again as Carrie Page.

Carrie invites Cooper in,

offering no explanation for what he finds inside, nor does he inquire, even though there is a dead man seated in a chair, shot through the forehead, blood splattered on the wall behind him, and a gun on the ground nearby.

Near the front door is the kind of chair that is set over a toilet seat for someone who needs to be higher and have arm rest assistance, a bucket and a packet of toilet tissue placed in it.

CARRIE (exiting to get her things): Give me a minute.

On the mantle is a white ceramic horse before a blue plate.

Are there a couple of open packets of Devil's Food Cookies on the fireplace below?

"My Prayer" had played while Diana and Cooper had sex in the motel. In New Mexico, the playing of the song had been coincident with the Lincoln Woodsman reciting into the DJ's microphone at the radio station, "This is the water, and this is the well. Drink full and descend. The horse is the white of the eyes and dark within." the horse had thus re-entered the conversation. Then outside Eat at Judy's we'd observed a children's mechanical horse that was white. The viewer will notice these things, while at the same time trying to comprehend why Cooper says nothing about the dead man in the chair. He's so focused on carrying Laura back to Twin Peaks, that everything else has ceased to matter.

The dead man, we may notice sits in a chair that's oversized, making him look peculiarly small. One might be reminded of the transformation chair in which we've observed tulpas created and extinguished, in which Dougie shrank. We may be reminded of Lucy's preferring a beige chair for redecorating Wally Brando's room, but getting the red chair that Andy liked. We may be reminded then of "This is the chair" and Major Briggs' wife removing from the wood trim at the back of a chair the pod in which was hidden the information concerning Jack Rabbit Palace.

We can find in this scene a certain amount of reframing of elements from Eat at Judy's. Outside there was the noose and within the house is the man with a bullet through his head. At the restaurant, Cooper had asked where to hang the fry basket, had then dropped the guns in the oil and advised everyone to watch out as he didn't know if the oil was hot enough to set off the bullets. To me, at least, this is a reframing of those elements. The hanging of the basket is expressed in the noose. The potential of the bullets being set off had been expressed, and here is a man who's been shot, though it looks like he's been dead a while.

The noose may also remind us of the agoraphobic man who had kept Laura's diary, how he had hung himself and torn her diary to pieces.

I think back to Andy in the chair where he'd had his vision, which ended with the #6 utility pole, and how he'd held a vessel that emitted a mist/cloud, precipitating the vision. After the vision the vessel had seemed to be reabsorbed into his stomach, and the dead man's stomach is bloated.

I also think back to how Mr. C had shot at Sheriff Truman, and Truman's cowboy hat had comically, briefly sprung off his head, as if popped up by the bullet, but Truman was unharmed. Then Lucy appeared at the door, killed Mr. C., and announced to Andy that she now understood cell phones. The only other time we'd had that cartoon-like incident was when Lucy was speaking to Sheriff Truman on the phone, on his way back from his fishing trip, and when she saw him standing before her, her chair jerked back in a very exaggerated, comic manner. It was then we learned she didn't understand how cell phones worked, apparently unable to comprehend the mobility of a person while on a cell phone. How she could come to understand cell phones when she shot Mr. C seems bound up with confronting the doppelganger of Cooper while Cooper is on the phone with Frank.

Whatever has happened, the scene is a disaster, and Dale says nothing about it. It's an impossible situation. Chaos reigns. Cooper and Carrie act, to a degree, naturalistically, in a completely irrational situation, for just as it is incomprehensible that Cooper doesn't question the body, it is also irrational that Carrie seems to expect Cooper not to say anything about the body. Carrie behaves as if it's not even there.

CARRIE (entering again as a phone begins to ring): Washington. Is that, like, up north? Do I need a coat?

COOPER: Take a coat, if you've got one.

CARRIE: I've got a couple. I'll grab one. (She exits then enters again with her coat.) Listen I don't have any food here.

COOPER:

I'll get us some food on the way.

CARRIE:

All right.

Let's go.

They exit.

As they drive out of Odessa, Carrie questions the veracity of what she's been told, as must the audience question Cooper's identity at least existentially.

CARRIE: Are you really an FBI agent?

COOPER (showing her his badge): Yes.

CARRIE: Well, at least we're getting out of this fucking town of Odessa.

Return to the top of the page.

THE LONG DRIVE

From 39:20 to 40:00 they drive through the dark night. At 40:00, headlights appear behind them, unnerving Carrie.

CARRIE (at 41:10): Is someone following us?

Cooper glances in the mirror but doesn't respond. At 41:50 the car passes and Carrie relaxes.

They continue driving through the night, in silence. Carrie finally speaks.

CARRIE (42:40): Odessa. I tried to keep a clean house, keep everything organized. It's a long way. (Drowsily.) In those days I was too young to know any better.

At 44:18 they stop at a gas station called Vallero. Two police cars pass on the road, then a third car. They pull out onto the road, heading in the same direction.

We see pines and realize they must be approaching Twin Peaks.

Anyone who has seen Lynch's Lost Highway will draw an immediate parallel between that film and this scene, and there are other comparisons to be made as well.

At the beginning of Lost Highway a man, Fred Madison, receives a message on the house intercome that "Dick Laurent is dead." After this he and his wife receive VHS tapes that reveals someone has done a recording in their house. At a party, Fred meets a strange man, one he had dreamed about, who it turns out is a friend of Dick Laurent. The man tells him not only had they met before but he is at that moment at Fred's house. Fred calls his house and the man, who is also at the party, answers the phone. Later, Fred's wife is killed, and Fred receives a tape showing him with her dead body. He has no memory of having murdered her but is sentenced to death for her murder. In prison he begins having headaches, then one night he is switched out with an innocent man named Pete. Fred is simply gone and Pete and is in his cell. No one can explain how this has happened, though apparently Pete's parents witnessed something very unpleasant. As Pete didn't commit the murder, he is released.

With the stranger being in Fred's house, one might be reminded of the Fireman telling Cooper that "it" is "in our house now".

Disequilibreated, Pete has a difficult time finding his bearings after the incident. He falls into having an affair with a mobster's mistress, Alice (who looks the same as Renee). Alice presents herself as desperate to get away from the mobster, who as a porn producer goes under the alias of Dick Laurent, and enlists Pete's help in robbing a man named Andy. During the course of the robbery, the man they rob is accidentally killed, so now Pete is a murderer. Pete and Alice go to a cabin in the desert. When Alice enters it, Pete turns back into Fred. He enters the cabin to find the stranger he had met at the party who pursues him with a video camera. Fred drives to the Lost Highway Hotel where he discovers his wife, seemingly still alive, with Dick Laurent. He kidnaps Dick and slits his throat. The stranger appears and also shoots Dick then disappears. Fred drives to his house where, at about dawn, he leaves the message on the intercom, "Dick Laurent is dead." Detectives arrive, having identified Fred's wife in a photo found at Andy's murder scene, and Fred flees. We see then several police cars pursuing Fred in the desert. The highway is suddenly engulfed in darkness and, the police cars still pursuing, Fred begins to shake back and forth, screaming, distorting, as had happened to Pete before he was replaced by Fred.

Fred, trapped in a kind of loop, on the lost highway is pursued by both his past, present and future. If one is familiar with this film, as we watch the car following Carrie and Cooper, we have the same anxiety, and Carrie questions if they are being followed. The car passes them, but then when they stop for gas police cars pass by and we are reminded once again of Lost Highway.

This is no ordinary drive between Odessa and Twin Peaks. In real life it has a Google estimation of 28 hours. If one pushes it and has good luck then one could perhaps make it in 2 days, but 3 is more like it. The viewer should be aware that this isn't a normal drive to make all in one day and night and may be somewhat discombobulated by it even if they aren't wondering what's going on, experiencing a complete suspension of disbelief.

The twin lights of the car that causes so much anxiety, Carrie wondering if they are being followed, may also remind of the twin lights in the scene with Naido in the presence of the #15 outlet. From behind the lights comes a chaotic banging from which Naido steers Cooper, as well as the outlet, to the exterior of the room where she throws a switch and is thrown into space. When Cooper returns to the room he finds there The American Girl who tells him, "When you get there, you will already be there." As I've already pointed out above, the twin lights remind as well of Duchamp's Etant Donnes, which may be referred to in Part 11, the art work through which one views, via twin peep holes in a door, the body of a woman, she holding a gas lamp, a waterfall viewed in the background.

Return to the top of the page.

WHAT YEAR IS IT?

At 46:32 they cross the bridge into Twin Peaks. They pass by the RR Cafe.

COOPER: You recognize anything?

CARRIE: No.

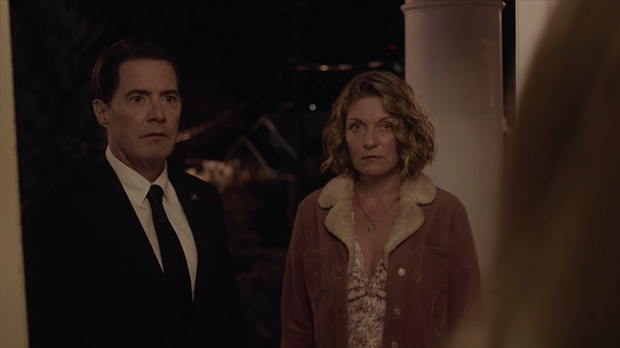

They pull up before the Palmer house and Cooper cuts off the car.

COOPER: You recognize that house?

CARRIE: No.

They climb out of the car and stand for a moment before the house before approaching. Cooper holds out his hand and Carrie takes it.

COOPER: Come on.

Cooper leads her up the stairs to the house and knocks on the door 7 times. We see, from inside a repeated knock of six. Then out on the porch Cooper and Carrie still wait. Finally, a woman comes and answers the door.

TREMOND: Yes?

COOPER (looking startled as it isn't Sarah Palmer): FBI.

COOPER: I'm Special Agent Dale Cooper. Is Sarah Palmer here?

TREMOND: Who?

COOPER: Sarah Palmer.

TREMOND: No, there's no one here by that name.

COOPER: Do you know Sarah Palmer?

TREMOND: No.

COOPER:

Is this your house? Do you own this house, or do you rent this house?

TREMOND: Yes, we own this house.

COOPER:

Who did you buy it from?

TREMOND (speaking to another off screen): Honey, what was the name of the woman who sold us the house? Chalfont, a Mrs.Chalfont.

COOPER:

Do you happen to know who she bought it from?

TREMOND: No, I don't, but...Honey, do you know who owned it before Mrs. Chalfont? No.

COOPER:

What is your name?

TREMOND: Alice. Alice Tremond.

COOPER: Okay. Sorry to bother you so late at night.

TREMOND:

That's okay.

COOPER:

Good night.

TREMOND:

Good night.

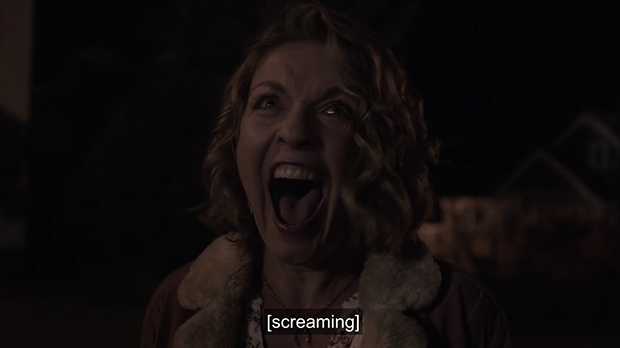

Tremond closes the door and Cooper and Carrie return to the road where they stare back up at the house. Haltingly bending forward, as if near incapacitated by beffuddlement, Cooper says, What year is this?

Carrie, staring at the house, hears a voice, Sarah's, faintly calling, Laura! Laura! Carrie screams as the lights of the house first go out then flare brightly, for an instant, as with a surge of electricity. Then all goes dark.

The end credits play over a still of Laura whispering in Cooper's ear in the Red Room.

Cooper is lost. Entirely lost. Which the audience would likely have never expected to happen to him, but seems destined since he woke and wondered over the Richard and Linda letter. He had forgotten things that he must remember. He stepped out the door of the motel room and was momentarily taken aback by the car not being immediately out front of the room, but he quickly adjusted to the fact that he was at a different motel and the car was across the parking lot, and crossed to it with a kind of suspension of disbelief that could be compared to a viewer's perhaps willingness to believe that the drive from Odessa to Twin Peaks could be made in a night.

The woman who plays Mrs. Tremond is the owner of the house at the time The Return was filmed, which some have construed to be Twin Peaks encountering the real world. This aspect may be there, but she is still named Tremond. Mrs. Tremond first entered the series when Donna took on Laura's Meals on Wheels route. Thus she met Mrs. Tremond, and her grandson, Pierre, the magician--a relationship that will always remind me of Lynch's early short, The Grandmother, in which a boy, abused by his parents, conjures a sympathetic grandmother who belongs to him alone. Donna's encounter was one in which reality was obviously altered outside the Red Room, and thus was unique in the world of Twin Peaks. Mrs. Tremond had become upset when she saw the meal delivered by Donna, and demanded if Donna saw creamed corn on the plate. She did. Mrs. Tremond said she had not ordered any creamed corn, and demanded again if Donna saw any on her plate. She didn't, it was instead in Pierre's hands, and then suddenly not. This was explained away as a matter of magic and Donna absorbed it as such, having no other way to explain it. Laura's second diary became known as it was the Tremonds who directed Donna to Harold. Pierre also addressed Donna with the phrase, "Je suis une ame solitaire", which is what Harold would leave in his suicide note. The second time Donna returned, with Cooper, after Harold's death, another woman named Mrs. Tremond was there, who was middle-aged. She said she had no children and her mother had died several years beforehand (her mother would not have been a Tremond, her mother-in-law would be a Tremond, but never mind). She did have for Donna an envelope from Harold, which turned out to contain a missing page from Laura's diary on her dream in which she whispered to Cooper. Again, reality had been obviously altered outside the Red Room. Cooper doesn't address this, and Cooper is usually drawn to little mysteries. He treats this instead like it must be a simple misunderstanding.

In Fire Walk With Me, Mrs. Tremond and her grandson were living at the Fat Trout Trailer Park when Teresa Banks was killed. Chet Desmond found the jade ring under their trailer and disappeared. At that time they were going by the name Chalfont, and someone else by the name Chalfont had previously lived in the same spot. Later, it was shown in Fire Walk With Me that Mrs. Tremond and Pierre had given Laura a painting to hang on her wall, which was associated with the room above the convenience store. Laura did so and dreamed of her and the room, the painting acting as a kind of portal. In that dream Cooper told her not to put on the green ring.

One of the unifying factors of interactions with Mrs. Tremond/Chalfont is the revelation of Laura's two dreams about Cooper in the Red Room, both his telling her not to take the ring (though the ring, which she took from Mike/Gerard, has been identified by some as the reason that BOB was not able to enter and control her body, for which reason BOB/Leland killed her), and the dream of her encounter with Cooper twenty-five years in the future. A unifying factor between the Tremond and Chalfont incarnations is the seeming ability to take the place of others, or appearing to do so, which fits in with their taking Sarah Palmer's place at the end of The Return. Should we be asking when Tremond/Chalfont entered the Palmer home--as in perhaps when Laura hung the painting Mrs. Tremond gave her on her bedroom wall, or was it after Sarah freaked out in the grocery store when she said it was different, focusing on the Albatross Jerky, worrying about "the men" who were coming (presumably The Woodsmen), and Hawk subsequently overheard a commotion in her kitchen which the audience sensed was perhaps what Sarah had feared, that it had entered and taken over her home? Or does the "when" even matter? Is it more, as the boy magician told Donna, that things can change "just like that"? Just as Sarah complained at the grocery store that, "Things can happen!" Just as things changed for Cooper the morning he woke up in Odessa and he seemed to briefly realize he was no longer where he had fallen asleep then entered the suspension of disbelief that carried him through the rest of the Odessa scenes and into the present?

It's been postulated that Carrie Page actually means "carry page" as in carrying what would seem to be the last missing page of Laura's diary. Considering the Tremond/Chalfont relationship to the diary, it could make sense that Carrie Page is indeed a reference to the diary. Also, back at the house in Odessa there were articles for the toilet in the living room, and the diary pages found by Hawk in Part 6 were hidden in a toilet stall door.

We can make association after association within the episodes. But what sticks? What matters in this 25 year long journey?

Return to the top of the page.

THERE IS NO DEFINITELY WRAPPING UP THE UNWRAPPABLE

I keep returning to Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf, the magical, imaginary child who comes too close to being accepted as real, and The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane who has been trapped in an isolated world created by her father, her only friend being a magician who assists her in camouflaging the reality of her situation, such as when he pretends to be her deceased father.

How would the audience have felt, at the beginning of The Return, if they knew that instead of having all the mysteries solved, some of them had to do with multiple rides down the same road, events repeated and slightly altering, which in Frost's follow-up book was explained away by everything changing when Laura didn't die? There are repeated inferences that what the viewer is dealing with are multiple timelines, of this road being traveled many times in the attempt to get a right resolution. I don't know about everyone else, but I wouldn't have been too pleased. In fact, at the beginning of The Return I imagined we might be on our way to such a resolution and wasn't happy about it, so I ignored that possible end and went along for the ride, which is what one does with Lynch anyway, you're there for the journey, I was present for the art.

Then, again, I wasn't too pleased when Sarah appeared to become a self-aware character and said to Hawk, when he visited her to make sure she was all right, "It's a goddamn bad story, isn't it, Hawk?" But when we got around to Audrey freaking out over feeling like everything was wrong, my relationship to this changed and I felt more at ease with her questioning their existence, which Sonny Jim never does in Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? as he never manifests, he is only ever a fantasy that Martha dangerously endeavors to make a part of the real world, for which reason her husband kills him, and in the manner in which he does so he curiously kills off a part of himself that he sometimes says experienced things that he otherwise represents as having occurred to other people and has also fictionalized.

Perhaps I was more comfortable with Audrey questioning her reality as her circumstances were so bizarre. I know that those scenes with Audrey changed how I felt about Sarah questioning the story. What I had initially thought of as a bit of a weary authorial trick--breaking the fourth wall with a character questioning their reality--was fleshed out with Audrey's confusion and became interesting. in Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, the fiction of the child, as the story of his death is told, becomes wrapped up with the Christ--a myth to some, a miraculous reality to others.

GEORGE: He is dead. Kyrie, eleison. Christe, eleison. Kyrie, eleison...Requiescat in pace...Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine...Et lux perpetus luceat eis.

One of the more wonderful things about Lynch, which is found with very few authors/scriptwriters (and Frost in conjunction with Lynch) is that it really is all about the ride rather than a plot that eventually ties everything up, all mysteries solved, all parts of the puzzle locked into place. Lynch not giving concrete answers means the viewer has to take the story as it comes, all the bits and pieces that are melded together by means of the conceit of a story that people expect to eventually be resolved--and so the ride becomes a story that fluctuates wildly but is bound to earth with these chapters concerning very believable characters and situations that explore emotional terrain in a unique way, that take on meaningful issues, as well as chapters and aspects that are entirely mythic yet so deftly handled that they feel real and are just as exploratory of the human condition rather than being only fantasy entertainment. Always, what is prompted is the viewer's continual exploration of "what is what" and "what if". So the terrain becomes less about the characters and Twin Peaks and more about the viewer's relationship to story being altered, and with that change in their relationship to "story" the audience is more directly impacted. This is something I've touched upon at several points earlier in the analysis, the manner in which the series teaches the audience to view it, and how the audience member, from the beginning, becomes a highly observant participant, having to pay close attention rather than relax back while the story rolls past. These demands made upon the viewer are not eased by the defeat of the doppelganger and BOB, which in another series, under another hand, would be climactic. In The Return, those two events are skated through, however dramatically, in an almost perfunctory manner. Cooper arrives after the doppelganger's death, and so doesn't confront him, and the doppelganger's death is remarkably abrupt. Cooper also isn't involved in the fight with BOB except to yell out encouragement to Freddie. The viewer waited through parts 1 through 17, expecting some great battle involving Cooper, and it doesn't happen. Then that pseudo-climax is promptly discarded, nothing is explained, and we're right back to wrestling with Lynch's mysteries as Cooper continues on with trying to save Laura from death and take her home, while Gordon instead describes Cooper as having been on a mission to find the negative force known as Judy.