Return to Table of Contents for films

We could start with Charles Dodgson's preoccupation with young girls and his shooting thousands of photos of them, sometimes in the nude, girls caught in their "daughters of Eve" state, before onset of maturity, as he would write to Mrs. Liddell, the mother of Wonderland's Alice. I was in college in the mid to latter 1970s and one of my professors was studying the aka Lewis Carroll's photography. [The book I'm thinking about, is perhaps Lewis Carroll's Photographs of Nude Children, by Professor Morton Cohen, published in 1978, containing four photographic studies of nude children. It was the first publication of such works by Dodgson, such photographs believed to have been entirely lost or even non-existing as on his death Dodgson had stipulated such prints should be returned to the models or their relatives, or destroyed.] This professor was one I'd met when I was sixteen, and was the reason I'd leave college due to sexual harassment. I don't recollect any conversations we might have had on Charles Dodgson, I just remember the book, and the itch of delight on his face, which was the enjoyment of the possible shock value of the subject and the arguments to come that would involve whether Carroll was a pedophile or a Victorian innocent infatuated with the innocence of the child and thus was he able to produce The Adventures of Alice in Wonderland for Alice Liddell, in tune with her innocence and the whimsy of childhood. Charles Dodgson, the photographer, was always a foot to the side and rear of Lewis Carroll, as was his relationship with Alice Liddell, his shadow hanging over her. Were we bourgeoise heathens if we were suspicious of his obsession with photographing the "ideal beauty" that was the nude body of a prepubescent girl "of about 12"? I was a young woman and such conversations, initiated by men, would seem to want to catch me like a deer in headlights. Somehow, in such discussions, the wrong or the right of it all got lost. It felt like a litmus test. The male, who initiated the conversation, would be a bit cagey with how they felt, keeping the subject very intellectualized and largely on the side of innocent-until-proven-guilty, largely on the side of there was no way the contemporary mind could pass judgment on the past. My reaction, I knew, was being carefully examined. I was the one on trial, somehow.

As for innocence, Dodgson's relationship with Alice was complicated enough that it drew the kind of attention that questioned propriety. Complicated enough that it reminds too much of Jimmy Savile, who got away with a hell of a lot, especially in the 1970s, and everyone was surprised by it all despite many knowing or suspecting what was going on. It was rumored Dodgson had proposed marriage to Alice via Alice's parents, and if that was the rumor, despite the fact girls could marry at 12, with parental consent, it feels like that wasn't really the rumor, it was instead a polite way of saying Dodgson was a problem. Also, girls marrying at 12 was relatively unheard of, however legal. Name me an upper middle class Victorian girl who married at 12. Even Edgar Allan Poe's cousin managed to be 13, and he was anxious enough that he presented her as being 21 on the marriage certificate.

Dodgson had met the Liddell family in 1856, when he was 24 and Alice was 4, the same year he had taken up photography, and Alice and her older sister Lorina (b. 1849), and sister Edith (b. 1854) were subjects. With over 60% of his original portfolio missing, over half of what remains are images of young girls, however given as taken with a parent in attendance. In 1863, a year after the fabled Alice in Wonderland picnic that birthed the book, his association with the family was put on hiatus, and when it was begun again he was no longer a companion of the children. We don't know the reason for his exile from the nursery as his relations cut the bits out of his diaries that covered the matter. Some now assume this was due his interest in Alice, however his nieces, who it's said cut out the forbidden parts, suggested he was interested instead in courting a young woman in the Liddell's employ, a governess, or was perhaps even interested in Mrs. Liddell. Further complicating matters, his diaries from 1858 to 1862 are missing, supposed to have been disposed of by the nieces.

After whatever it was happened, Mrs. Liddell destroyed all the letters Dodgson had written Alice.

Alice's sister Lorina would later write to Alice, on the alienation,

"I said his manner became too affectionate to you as you grew older and that mother spoke to him about it, and that offended him, so he ceased coming to visit us again."

Still, it's debated that Charles might have been interested in the governess or Mrs. Liddell or even Lorina herself and Lorina was lying about the matter.

Though Alice gets all the attention, Dodgson had many such alliances with young girls, including Evelyn Hatch, who Dodgson photographed as a languid, Gypsy-like nude in 1879, when she was 8, and who he took "on trips or other outings that lasted overnight or for a weekend" (according to Wikipedia).

In 1857 Dodgson had befriended John Ruskin, who had fallen in love with Effie Gray when she was 12, had written for her the fantasy, The King of the Golden River, then married her in 1848 when she was 19 and he was 28, but he was repulsed by her mature female anatomy and when they divorced the marriage was unconsummated. Afterward, she married John Everett Millais who forever loathed Ruskin for the emotional violence he'd perpetuated on Effie and the suffering he'd caused her. There's still debate about Ruskin but he wrote a former "pet", Lady Jane Simon, in 1886,

"How little you know me, after all! As if I ever cared about marriages! The moment people marry I drop them like hot coals. Go suckle your babies and don’t bother me! I just [agreed to] let Mary Gladstone write to me still on condition she never signs her married name. I like my girls from ten to sixteen--allowing 17 or 18 as long as they're not in love with anybody but me--I've got some darlings of 8--12--14, just now, and my Pigwigginia here--12--who fetches my wood and is learning to play my bells."

As with Dodgson, it's contended that what Ruskin adored about girls was their sexual innocence and that he had no sexual interest in them. His interest in young girls was instead his way of avoiding sex, just as is said about Dodgson.

Excuse me but I keep revisiting, in amazement, the "who fetches my wood and is learning to play my bells" quote.

John Ruskin pursued Alice Liddell as well, but his attentions were dissuaded by her parents. He wrote the following of one evening spent with Alice.

"For that evening, the Dean and Mrs. Liddell dined by command at Blenheim: but the girls were not commanded; and as I had been complaining of never getting a sight of them lately, after knowing them from the nursery, Alice said that she thought, perhaps, if I would come around after papa and mamma were safe off to Blenheim, Edith, and she might give me a cup of tea and a little singing, and Rhoda show me how she was getting on with her drawing and geometry, or the like. And so it was arranged. The night was wild with snow, and no one likely to come round to the Denery after dark. I think Alice must have sent me a little note, when the eastern coast of Tom Wuad was clear. I slipped round from Corpus through Peckiwater, shook the snow off my gown, and found an armchair ready for me, and a bright fireside, and a laugh or two, and some pretty music looked out, and tea coming up.

"Well, I think Edith had got the tea made, and Alice was just bringing the muffins to perfection--I don't recollect that Rhoda was there; (I never did, that anybody else was there, if Edith was; but it is all so like a dream now, I'm not sure)--when there was a sudden sense of some stars having been blown out by the wind, round the corner; and then a crushing of the snow outside the house, and a drifting of it inside; and the children all scampered out to see what was wrong, and I followed slowly;--and there were the Dean and Mrs. Liddell standing just in the middle of the hall, and the footmen in consternation, and a silence,--and--

"How sorry you must be to see us, Mr. Ruskin!" began at last Mrs. Liddell.

Just as Dodgson went from family to family, girl to girl, so did John Ruskin. After Effie Gray, in 1858 he met and became infatuated with Rose La Touche when she was 10 years of age. When he later proposed marriage, before Rosa was of age to decide for herself, her parents said no, having been warned about Effie Gray.

In 1883 he begged of illustrator, Kate Greenaway, who sent him drawings of children,

As to those drawings of sylphs: Since we’ve got so far as taking off hats, I trust we may in time get to taking off just a little more—say, mittens—and then—perhaps—even—shoes!—and (for fairies) even—stockings—And then—

My dear Kate…it is absolutely necessary for you to be—now—sometimes, Classical. I [send back to] you—though heartbreakingly…one of those three sylph [drawings] this morning. WILL you (it’s all for your own good!) make her stand up—and then draw her for me without her hat—and without her shoes (because of the heels)—and without her mittens, and without her frock and frill? And let me see exactly how tall she is—and how—round.

It will be so good of—and for—you—and to—and for—me.

It's reported the Ruskin's caretaker got hold of the letter and added in pencil, "Do nothing of the kind." Ruskin, learning, this, wrote to pay no mind to this and that the caretaker, Joan Severn, simply didn't like the word "round". The Ruskin scholar, Rachel Dickinson, asserted, ""But the symbolic association of this fascination with waists is not necessarily sexual. Rather, the idea of waists which were allowed to be naturally ‘round’ or ‘oval’—without the unnatural constraints of corsets and stays—is representative of freedom. It is also typical of the free-flowing dresses worn by girls and boys at the time Ruskin himself was an infant." Ruskin, she asserted, was not a pedophile, he was an aesexual aesthete just wanting to share with his children "pets" a sense of the sweet childhood he'd missed.

One is either going to think, "You know, I believe that Dodgson and Ruskin and the like were misunderstood innocents, there's no evidence otherwise", or one is going to think about how then, like now, like in the 1970s, predators, when found out, were quietly dissociated from contact with the known abused, about whom none of this was publicized because no one wanted the attention, and thus were predators able to go on from situation to situation, abusing, especially as members of the middle class and upper middle class.

But what does any of this have to do with New Orleans' Storyville red light district and Ernest Joseph Bellocq, the photographer who recorded it, about whom, in 1976, was published the book, Storyville, New Orleans, Being an Authentic, Illustrated Account of the Notorious Red-Light District? Well, Barbara Steele, who had been in a relationship with Louis Malle, introduced him to the book, which resulted in Pretty Baby, but, I've searched everywhere for any references to Bellocq having photographed children in the nude and found none. Instead I only see that he recorded adult, female prostitutes. Louis Malle, himself, in an interview, stated that Violet was based on an interview he'd read with a an individual prostituted as a child in Storyville, recorded when she was an adult, in which she was entirely frank and unashamed. Malle seemed to feel that she had suffered, ultimately, no ill effects from that period in her life.

Charles Dodgson was getting attention in the mid 1970s, and so then were the photographs of Storyville's prostitutes made by Ernest Joseph Bellocq. Though I don't see it recorded that Bellocq had any kind of association with children, I see nothing about his photographs involving children, there was included in the book an interview with Violet, who was born into prostitution. Louis Malle, in interviews, speaks of this, of her as an inspiration, and seems to feel that Violet didn't feel very abused by it all, and takes her representation for granted. I thought I'd publish the entire interview here.

Warning, it is frank and rough.

I was born in 1904 in the wintertime. I was a 'trick' baby. That means my father was just one of them johns that paid my mother for a fuck. I was born upstairs, ike in the attic of Hilma Burt's house on Basin Street. A lot of kids was born in that attic and in the Arlington attic and other places like that. There was a midwife used to come...for all the girls who got caught. Why do people think whores can't have kids?

I read in a a book one time about one of the houses that was selling a mother and daughter combination for fifty collars a night. The man that wrote the book acted like that was some kind of freak act or something. Well, you can write the truth is that I remember fifty combinations like that and I was one myself, and I know two girl friends, both still living, that were in the same kind of act. I ain't ashamed of what I did, because I didn't have much to do with it. I don't blame my mother much, either. I ain't no more ashamed of that, anyway, than I am to be a member of the human race. The johns can't help it either, you know. It ain't their fault. Just seems like the good lord ain't got good sense.

Nobody never stopped me from seeing my mother and the rest of the girls turn tricks. I don't remember anytime when I didn't know what they did, or what a man's prick looked like.

One night when I was ten years old I walked into the bedroom where my mother turned her tricks. The john was in there with her and had his pants off. She was, you know, washing off his prick with a wash cloth. She said this is my kid. He said don't I think a good little girl ought to help her mother. They both laughed. My mother asked me if I wanted to help and she held up the wash cloth. I didn't think nothin' of it. You know, like I said, I seen so much of this from the time I was born. So I took the wash cloth and washed him off, and they both laughed and he gave me a dollar. Well, that routine went over so big, pretty soon all the other girls were laughing about it, and then my mother used to get me to do the wash-up act every time she turned a trick. I'd get one and two dollar tips nearly every time, and then the other girls started gettin' me to wash off their tricks, too, before and after, and Edna got the word around it sure helped business. I was takin' in maybe a hundred dollars a week myself, and the other girls was gettin' more johns.

...The first time I ever got fucked wasn't at Edna's but at Emma Johnson's--you know, they called it the Studio on Basin Street next to the firehouse. I was twelve and Edna had been sendin' me over there nights to be in the circus two or three nights a week. There was another kid my age...Liz...we used to work together. By this time we were getting a little figure and looked pretty good...and neither one of us was afraid to do them things the johns liked, so we'd get a hundred a night to be in the circus. My mother was in the circus, too. She's the one who used to fuck the pony. Emma kept a stable in the yard and a colored man, Wash, to take care of the two ponies and the horse. In the daytime me and Liz rode the ponies around the yard...Ain't that somethin'?

So this one night, Emma had some live ones in the house and she says to me she thinks I'm ready to fuck, and will I do it for half of what she gets for me. Usually I never talked anything over with my mother anymore, but this time I did. She said that since I was getting hair on my cunt, I might as well go ahead. So Emma she had a big mouth--a loud voice, made a speech about me and Liz and how everybody in the District knew we was virgins, even though we did all these other things and that if the price was right , tonight was the night and she'd have an auction. Some snotty kid bed a dollar and Emma had one of the floor men slug him and throw him out in the street. One man bid the both of us in, honest to God, for seven hundred and seventy-five dollars each! A lot of Johns bid and he wasn't gonna be satisfied with just one. He bought us both. Well, we went upstairs with him. He wanted us both together, and you know how it is, we thought he ought to be entitled to somethin' for all that money, so we came on with everything we could think of, includin' the dyke act which we been doin' anyway in the circus and we got to like it so much we'd lots of times do it when we was by ourselves. We did a dance we had worked out where we jerked ourselves and each other off and we started to play with him, but I didn't hardly touch him when he came. Well right away he went to sleep with us on the bed with him and in a little while, maybe an hour, he woke up, and the three of us fooled around until he got in shape to do something and we managed to get him into Liz. I could tell it hurt her and she bled pretty good too, but afterwards she said it wasn't so bad and she was glad it was over. But the John didn't have enough left to do nothin' with me so he arranged with me and Emma to hold me over to the next night.

The next night he came around to Edna Hamilton's and that's when I got broke in. It wasn't bad, and he really thought, all around h had his money's worth.

The next year the district closed down. I had money saved and I got a job. I was always high priced. Not because, you know, I was so pretty or nothin', but because I was a novelty, and I didn't hang around long enough to get wore out.

...I don't know if it was a good life or a bad life. I know I got a good life now, and I know how to appreciate it. But I don't know how I'd feel about it if I went through the whole life, you know, with pimps and dope and turning tricks till I was fifty.

All my three girls is older now than I was when I quit the business, and I don't see that they'r'e much better off than I was at their age. I know it'd be good if I could say how awful it was and like crime don't pay--but to me it seems just like anything else--like a kid whose father owns a grocery store. He helps him in the store. Well, my mother didn't sell groceries.

SOURCE: The Storybook Version of Storyville, Janis Kelly, "Off Our Backs", Vol. 8, No. 6, June 1978. From Al Rose's, Storyville, New Orleans, Being an Authentic, Illustrated Account of the Notorious Red-Light District .

Malle's Pretty Baby has almost nothing to do with Violet's story. Violet doesn't even begin to comprehend how she was degraded. She allows that she appreciates the good life she has outside the business, while at the same time not seeing how her daughters really have it any better than she did as a youth. She rather sounds as if she was running her own brothel, or a prostitute, she wouldn't think twice about involving her daughters. Violet's sense of boundaries have been totally wiped out except, perhaps, for making sure one gets paid.

Interesting to me is that Violet says she wasn't high priced because she was pretty but because she was a novelty, and this means, despite Violet giving the impression this was common, that she was to some degree a rarity.

There are numerous stories out there in which women could describe demoralization and abuse in prostitution. There are stories that instead would point out the necessity of the business for some women, providing them income. Malle seems to have been attracted to Violet's story because she was raised in the trade of prostitution, because she considered herself unscathed by it, and because she offers no judgment on it at all. It's no different from any other job, and is thus to be expect that one would initiate one's child into the business. He accepts this, and even, in an interview, claims everyone else but Violet becomes a victim, because she has no shame in what has happened. Rightly, Violet should have no shame over what she did as a child, or what happened to her, but there is shame to be placed, and Malle seems not to recognize trauma and how Violet has been subjected to such violence in the dissolution of boundaries she can't place blame on anyone and doesn't see how any of it is not normal.

Louis Malle: She was so matter-of-fact about it. She described it as something that was. And she had absolutely no sense of guilt, shame, of anything. She said well that's the way I was raised and I knew nothing else. And she said things like, maybe, the only thing I could say is if things went that way it's maybe because the Good Lord ain't got that much good sense. That's all she had to comment about her situation. It's about a world with a different system of values.

While in the 1970s academics and others are discussing the Victorian innocence of Charles Dodgson with the newly released book of his nude photographs, fresh scandals of "Is this abuse, is it art, if it is art can art be abusive?" were taking place in a high profile way. French photographer Irina Ionesco, who had been photographing her daughter, Eva, in provocative, fetishistic ways, Eva a subject since she was four years of age, was to gain a significant following for her photographs, the first gallery exhibition taking plac in 1974 at the Nikon Gallery in Paris. Born in 1965, Eva was then only 9 years of age. The popularity of the photographs was such that other exhibitions followed and the photographs were reproduced internationally in a variety of publications.

In an interview with Liberation.fr, Eva told Anne Diatkine that beginning at the age of 10 she was "sold to photographers, "notably" fashion photographer Jacques Bourboulon, for erotic photos, becoming purportedly his most famous model.

"Eva garde en tete qu'a 10 ans, elle a ete "vendue" a des photographes, notamment Jacques Bouroulon, pour faire des photos erotiques."

Wikipedia notes that at the age of 11 she became the youngest model to appear in a Playboy nude pictorial, featured in a set of photographs by Bourboulon in the October 1976 Italian edition. In November of 1978 photos of Eva by her mother appeared in Spanish Penthouse.

On the American side of the pond, in 1975, the fashion photographer, Gary Gross, photographed for Playboy's Sugar and Spice twelve images of Brooke Shields which Gross said were intended to "reveal the not-so-latent sexuality of the prepubescent child". As the photos appeared in Sugar and Spice, though this was a Playboy publication, they are not considered themselves to have been published "in Playboy". Brooke, who had been modeling professionally since she was 11-months-old, appears in the photos with her face heavily made-up, standing and sitting in a bath tub, and covered with oil. The images, made with Brooke's mother's permission, and for which they were paid, caught the attention of Louis Malle, for which reason she appears as "Pretty Baby". Following Brooke's success in Malle's film, and the famous/infamous Richard Avedon ad campaign for Calvin Klein Jeans, in which Brooke's declaration was that nothing came between her and her Calvins, her mother, in 1981, attempted to sue Gross, claiming his continued sale of them was damaging to Brooke's reputation.

Gross’s lawyers argued that his photographs could not further damage Shields’s reputation because, since they were taken, she had made a profitable career "as a young vamp and a harlot, a seasoned sexual veteran, a provocative child-woman, an erotic and sensual sex symbol, the Lolita of her generation". The judge concurred and, while praising the pictures’ "sultry, sensual appeal", ruled that Gross was not a pornographer: "They have no erotic appeal except to possibly perverse minds." That decision was overturned by an appeals court, but in 1983 the original verdict in Gross’s favour was upheld.

"Sugar and Spice and all things not so nice", Christopher Turner for "The Guardian", October 2009

In 1976, Eva would have a small part as the mysterious child of Madame G. in Roman Polanski's film, The Tenant, in which Madame G. protests to Roman the real or imagined abuses she says she and her daughter have suffered at the hands of the other tenants, Roman feeling also persecuted. Shelley Winters plays the concierge of the apartment building and is briefly viewed with what appears to be a Playboy style magazine featuring the photo spread of a Lolita-like Maryanne La Fille de la Mer, which recalls Shelley's turn as Lolita's mother in Kubrick's Lolita. The identity of Madame G.'s daughter is confused when it's later insisted that she has instead a son, but that Roman should ask the concierge about the matter. In 1977, Polanski, at 43, was arrested and charged with, according to Wikipedia, "six offenses against Samantha Geimer, a 13-year-old girl--unlawful sexual intercourse with a minor, rape by use of drugs, perversion, sodomy, lewd and lascivious act upon a child under 14, and furnishing a controlled substance to a minor."

While Brooke went on to appear in Pretty Baby, Eva, who has claimed her story served as inspiration for Malle's film, when 12 years of age, in 1977, was removed from her mother's care, by social services, due to her mother's persistant, problematic photography of her. Eva has asserted her mother was abusive and in 2012 she won a judgement in which her mother was ordered to pay her damages and transfer to her all negatives of the nude photos taken when she was underage.

Brooke Shields, who apparently felt loved by her mother, and loved her mother, has revealed that from a young age she was her mother's caretaker, struggling with her mother's alcoholism, attempting to rehabilitate her image. She has said she did not ever feel exploited by her work on Pretty Baby, that she was emotionally well-protected, a labor of love by everyone concerned, and what was traumatizing was leaving the cast and crew, this new family, behind at the end of production. I don't know how she feels about the photos taken by Gary Gross. If anything, as far as Terri Shields' management of Brooke's career, they were a PR coup, exposure bringing opportunity bringing more exposure, though one still wonders at the wisdom of the 1975 photo shoot, which Shields apparently doesn't address in her autobiography. And as far as if a young daughter of hers was offered a similar situation to Pretty Baby, in today's atmosphere and "just being a mom now, looking at my 11-year-old" Brooke says she would not "facilitate" it.

Eva's relationship with her mother was different, and her history was one of continual crisis relieved with some of the advantages of privileged connections. She did not have a good childhood. She was exploited. In an interview for Purple magazine, she said of her mother, "She knew she was doing something unique and that it would advance her career and earn her money, but she also knew that it was monstrous. She took on that role, assuming the consequences it would have on our relationship. She knew there was something poisonous about what she was doing...Granted, it was a more tolerant moment, but not for photographs of women showing their vaginas, with very young children. There was never any tolerance for that. Even though the images are baroque, even if you think they are artistic, these photographs were very controversial. And as soon as something is controversial, there is a risk. She knew full well what she was doing when taking that risk."

Historian Al Rose’s book Storyville, New Orleans, is one of the main inspirations for the film Pretty Baby. However, Rose claims that the film is inaccurate and although he had been paid for the rights to the book, he was "ignored." One discrepancy in the film, Rose claims, is "the presence of both black and white prostitutes in the same bordello." Also, Rose stated that Louis Malle "sensationalized" the story of child prostitute Violet, which was so brief a segment in his book. The book contains a short interview with the real Violet in which she states, "I know it’d be good if I could say how awful it was and like crime don’t pay-but to me it seems just like anything else-like a kid whose father owns a grocery store. He helps him in the store. Well, my mother didn’t sell groceries"(Flake 1978).

Source: ViaNoaVie, April 27 2012

It's a problem when the historian who wrote the book you're making a film about says, "It wasn't like that!"

There are a lot of tough questions that should have been asked Louis Malle about this movie, which drew both appreciation from an artistic perspective, but backlash for its also being possibly exploitive and a rather glamorized representation of the life of the child prostitute.

Listening to a Studs Terkl's interview with Louis Malle, dissatisfied with his answers, even when his answers seemed to say he was making an anti-exploitation film about exploitation, I began to feel that there was possibly no getting really, honestly close to Malle's relationship to the film as he was too close and identified too much with the character of Bellocq, who is wholly fictionalized, and represented as seduced by Violet. When she moves in with him, she insists they will sleep together and have sex. He says no. She applies her charming, seductive wiles, and he says yes.

Photography is an illusion too: Hattie is made to look "like an angel," which she wasn’t. Bellocq himself says he’s dealing with magic. The whole context of the film is an illusion. I took advantage of the fact that it was taking place in New Orleans, where voodoo is so important. They live in a strange world and believe in a lot of irrational things. And of course, Bellocq, "the artist," is a man who is trying to track down an illusion. Photography is an illusion, filmmaking is an illusion ... I felt extremely close to the character of Bellocq—I very much identified with him and when I directed Keith, I deliberately made him behave like a movie director. In the photography session in Hattie’s room, when he tells her those stupid things: "You’re beautiful! Perfect! Don’t move! It’s going to be great!" This scene has heavy sexual overtones. Bellocq tells Violet to leave the room and then asks Hattie: *Are you ready for me?"" It was meant to be the transposition of a sexual dream, where actual sex is replaced by . . . Definitely, for Bellocq, his art is a means to get rid of an obsession which has to do with sexual fantasy. It’s an obvious transposition of sex into something else, which supposedly creativity is all about.

Those moments that Malle remarks on struck me as odd when I was watching the film. When Bellocq said, "Are you ready for me?" I wondered about the language. It was off. It stood out as false and representing something that didn't have anything to do with the story about the child prostitute. I began, watching the film, to wonder if Malle was identifying the photographer with himself. I'm not implying that Malle had a predilection for young girls, instead I would say that the lines blurred between the photographer and himself with his making assumptions about the character that were false, that had nothing to do with the reality of a man attracted to young girls, how he perceives them, his manipulations of them, his relationships with them.

Malle decides that "supposedly" creativity is all about sex. That is not definitive. That is Malle's interpretation. It is not an absolute, as he appears to suggest with his "all about".

As it turns out, Louis Malle was of the belief that Dodgson was an innocent. He was politely obsessed and could not have done anything inappropriate because he was a polite photographer and therefore necessarily too repressed to do anything but dream erotic photos into reality.

This obsession with children, with girls, which is totally sublimated, totally transposed — God knows they’ve been trying to find all kinds of sexual perversions in Lewis Carroll but they don’t seem to be able to dig out anything really serious. Technically, it was sort of a-sexual and it seems that just talking to girls, taking them for boat trips or photographing them was enough to satisfy his fantasy. It’s very mysterious. There’s something opaque about him. This sort of double-life he led: being a very respectable clergyman on the one hand and a mathematician and teacher on the other— his odd relationships with girls, how he dealt with their parents . . .It’s very Victorian, very proper: asking the parents’ permission to photograph the girls naked . . . and being so prudent and careful about the whole thing! The result is similar to Bellocq’s photographs — it’s stunning how he managed to capture . . . Some of these Lewis Carroll photographs are very erotic, because they convey a very strong obsession.

Source: Louis Malle: An Interview from "The Lovers to Pretty Baby", Dan Yakir; Louis Malle, Film Quarterly, Vol. 31, No. 4. (Summer, 1978), pp. 2-10.

Rather than this picture being about Violet, who works in Storyville, I think Malle's interpretation of the subject matter has more to do with his feelings about Charles Dodgson. He has scripted Bellocq to be a Charles Dogson, despite the fact that Malle asserts in interviews that Dodgson didn't abuse children. I will return to this subject later.

The film opens with Violet watching her mother give birth, but at first we don't know if the noises she makes might be instead from her having sex. The child is confronting her future, this is what life has in store for her as a woman, which is also a confrontation with mortality as a woman might die during childbirth. After, when she runs down into the brothel to proclaim the birth of a boy, she first opens a door upon a prostitue having sex with a man and is obviously unabashed, this she is used to, then she descends to the social area. At the bar, she approaches a young woman, of about her height, a prostitute who is dressed up as a child with bows in her hair and a girlish lace dress, contrasting with and paralleling the real child. Violet finally informs the African American piano player who greets the birth of the child with a song for that "pretty baby" her momma has brought against his will into this cruel world.

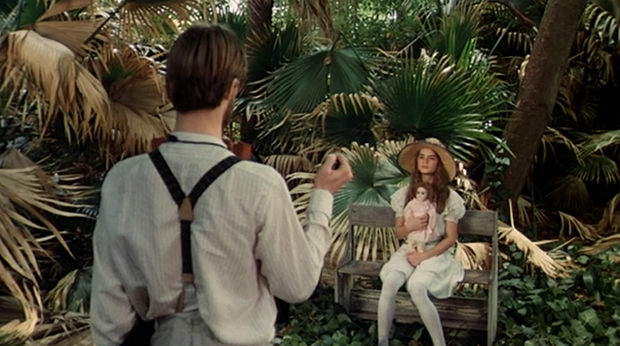

Having introduced us to the social scene of the brothel, Malle proceeds to the everyday life, Violet waking in the morning in a situation where the children room together. It is some months later, and as her little brother requires nursing, she goes to wake up her mother who is still asleep with a john. Finding her mother has, purportedly, real emerald earrings, gifted her by the man, Violet declares she wants them. We see the workings of the household so that it will become more real to us--the Black servants in the kitchen, the piano being tuned, Violet helping the elderly Madam Nell start her day, who requires absinthe. Outside, Violet plays with another girl on a horse, which is Malle referring to the Storyville's real Violet who would play with another girl on the pony that was used in sex acts with her mother in the circus, though this information is left out. We realize that a "benefit" of the lives of the prostitutes in this brothel is that they don't have to labor at normal household chores, and that they consider themselves higher in the social order than the servants. Violet's mother sitting in the kitchen with her boy, Will, Violet answers the front door to find the photographer, Bellocq, standing there. Assuming he's a peddler, she dismissively tells him he needs to use the back door. When he comes around back, she curiously answers the door, and Bellocq introduces himself to the madame who hasn't much use for him. She isn't interested in buying, and, as for the photographer as a customer, she assesses him, remarks that he's "rabbity", and says, "I don't cater to inverts." But he's willing to pay the prostitutes for his time photographing them, so he's given access.

Alice was beginning to get very tired of sitting by her sister on the bank, and of having nothing to do: once or twice she had peeped into the book her sister was reading, but it had no pictures or conversations in it, “and what is the use of a book,” thought Alice “without pictures or conversations?”

So she was considering in her own mind (as well as she could, for the hot day made her feel very sleepy and stupid), whether the pleasure of making a daisy-chain would be worth the trouble of getting up and picking the daisies, when suddenly a White Rabbit with pink eyes ran close by her.

There was nothing so very remarkable in that; nor did Alice think it so very much out of the way to hear the Rabbit say to itself, “Oh dear! Oh dear! I shall be late!” (when she thought it over afterwards, it occurred to her that she ought to have wondered at this, but at the time it all seemed quite natural); but when the Rabbit actually took a watch out of its waistcoat-pocket, and looked at it, and then hurried on, Alice started to her feet, for it flashed across her mind that she had never before seen a rabbit with either a waistcoat-pocket, or a watch to take out of it, and burning with curiosity, she ran across the field after it, and fortunately was just in time to see it pop down a large rabbit-hole under the hedge.

Source: Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

Bellocq's first venture is with Hattie, Violet watching. Though he seems initially irritated with Violet, he remarks on her beauty, and Hattie says Violet is her sister, but Violet objects and reveals she's her daughter. When Hattie's john finally wakes and storms downstairs looking for her, infuriated she has left him alone, he rips the emerald earrings from her ears. They fight it out, and Malle treats this episode of abuse as a normal amusement, even entertainment, Violet and others laughing over the brawl.

Malle is going to be interested in New Orleans for its French history and what has been absorbed into the white culture from the beliefs of Africans imported and sold as slaves. The brothel is depicted as relying upon voodoo women for certain types of medical advice, the practice of herbalism, telling the future, and spells for banishing evil and bringing good luck. One such woman applies a blue paint/ointment to Violet's left leg, red-orange to her right, and declares she'll be lucky and have many men. In the meanwhile, the photographer arrives with a photo for Hattie. He tells Violet he did it with magic, Malle thus making Bellocq the wizard of the brothel and film.

Hattie's lover, the gambler who gave her the earrings, causes trouble and is knocked out and ejected from the brothel. Hattie threatens to leave because of this, declaring her mother was a prostitute, which is why she's one, and she's sick of it. She wants to be respectable. She's told that it's the respectable people who are lying on her every night. Because Violet refuses to go with her, Hattie must stay and angrily blames Violet for her lack of freedom. In the "real life" Violet's story, the family situation was such that the mother was not given as wanting to become "respectable", or that she was sick of prostitution, and Violet even felt that it was fine for her to be involved in it as a child, as it was just a business. We were even given the impression she would have involved her own daughters if she were still a prostitute. Malle has said if there was a "message" to the film, it is this, the remark concerning those who are "respectable" and uses the scene to make it clear to the viewer that the johns, those who have daylight lives, are the ones to whom the prostitues owe their living and social degradation, and that the johns fuel the sex industry with their desires. Malle asserted he wanted the audience to absorb they are all responsible for the predicament of the prostitutes, and believed that this was most difficult for Americans. He wanted the spectator to participate and draw their own conclusions.

A discussion between Violet and the photographer reveals he only photographs the prostitutes but doesn't go upstairs to have sex with the women. She's puzzled by this. She wants to know if he thinks she's pretty. When she demands to know why he doesn't have sex with the women, he replies, "That is for me to know and you to find out", and though this seems off-handed, it is also somewhat coy. Violet informs him that the Madam thinks he's a cream puff. When he replies he doesn't want to explain himself to a child, she protests she's not a child, and he tells her that's her opinion. When she gets upset and says he hates her, he grasps her hand and soothes her, telling her he has no time for hate or love. Afterward, when a man seems to display an interest in Violet, asking Madam Nell if she's now into white slavery, Nell whispers to him a proposition concerning the girl, and he immediately backs off, saying that's not his thing.

The next scene shows that Violet is being used in the house's sex trade. She has a discussion with one of the prostitutes that reveals the hopes of many, that one of the rich johns they service will fall in love with them and marry them. Violet had earlier questioned the photographer if he was very old and might die soon, and she perceives this prostitute as associating with a very old man, which is offputting to her but not to this other woman who is interested not in him but his ability to transform her life. The prostitutes only act as if they love the men, not caring for them. After this, Hattie enters the room and shows off her daughter to a client, willingly revealing Violet is her daughter. Though she tells him she's just "friends" status as she's still a virgin, she quietly nods to Violet to follow them to her room. At the door, Violet stands and watches as they undress, then closes the door to the room behind her, signifying that she will also be involved somehow in their sexual activity as a mother-daughter team. Despite her typical bravado, she looks hesitant.

The mother and daughter theme continues with the photographer shooting Violet and Hattie together. Hattie uncovers her breasts for him, and Violet begins to become jealous when the photographer tells her to leave and he puts his attention into positioning her mother for the shot. Violet preoccupies herself with looking at his equipment, and as she begins to open a photo plate, he catches her and slaps her, yelling that she is never to do that. Violet, sobbing, throws herself on a bed, and accuses him of loving her mother. He apologizes for having struck her.

Violet is fitted for her auction dress, and while this is happening her mother sits nearby reading a book on hands (perhaps how to tell fortunes with them). A friend of Violet's, a boy her own age, Red Top, brings her the 9th bone from a tail of a black cat guaranteed to bring her luck that night. She mimicks with the other women and chlldren how she's supposed to flirt/act with a john. At the auction she 's first carried in on a stretcher, holding a sparkler, her nude form veiled. We hear, "How old is she?" Madam Nell answers, "Do you want to put me in jail? She's just old enough." Attired in her white auction dress, Violet is sent back out to be sold, barefoot, something in how she's portrayed, despite the lace dress, vaguely reminiscent of Charles Dodgson's photograph of Alice Liddell as the eroticized beggar child in a torn costume, barefoot. As bids are made on her, Malle gives us shots of men looking longingly on her, including the photographer. She is finally sold for 400 to someone they don't know, who is said to have just kind of shown up. He gives her a drink of whiskey. She tells him she can feel the steam inside her right through her dress. Hattie watches, unaffected, as he carries Violet upstairs. In the room with Violet, he becomes upset when he realizes there's no lock on the door and Violet tells him the Madam permits no locks. She asks him to be gentle, and despite her acting otherwise she is obviously nervous as he undresses. From outside we hear her scream as the other children look on at the door. Malle then shows everyone waiting, and then the man who was with Violet hurries down the steps and leaves without a word. The women go up to see Violet lying on the bed, who says nothing, and at first it even appears she may have been killed. One of them runs out yelling she has been murdered. Violet then moves and scolds them for not having arrived sooner, but she is joking. She has been, as far as they are all concerned, initiated. She moves to stand and sits back down because of the pain. She laughs about it with everyone but is obviously hurt.

In the next scene, Madam Nell leads a man upstairs telling him the girl is a virgin, asking how did he find out about her place. A friend. "Well, if you can't trust a friend..." We next view Violet in the bath, a breast exposed, examining a toe, a foot crossed over her knee. When the man enters she rises, briefly almost fully exposed, and grabs something to put around her. The Madam takes the towel from her. "Pure as the driven snow."

This is the first time that Malle shows Violet in the nude, and it is after she has lost her virginity, having supposedly become a woman. The Violet in the Storyville book had described how at 12, when she was auctioned, she had gotten a figure. It makes no difference the state of physical maturity, they are still children--but that isn't the Violet of the movie. Her body is that of an immature girl. I am personally reminded of how Brooke Shields, herself, had been heavily made up for Playboy's Sugar and Spice and photographed nude in a bath tub at the age of ten.

At a lavish dinner, a toast is made to a quick end to the war. A bird enters the room and flies about, which is bad luck, signifying death. It has to go out the same way it came in. The photographer catches the bird and carries it outside into the rain, and everyone seems pleased--but it hasn't gone out the way it came in. Hattie and a former john enter and announce they are getting married in St. Louis. She tells Violet he knows about Will but that he thinks she's her sister. She promises to send for Violet at some point later and leaves.

By now, all the women in the brothel have taken to calling the photographer pappa. They play a game called "sardines" with him. He hides. They look for him. Violet finds him in the attic where he is hidden among costumes and masks. She kisses him and asks if he liked it. He doesn't answer but his attraction to her is obvious. Immediately discovering them both there, the rest of the women pile in. We hear one exclaim, "Papa ain't no cream puff!" As they leave him, only a little disheveled, Violet calls to him, "I love you once, I love you twice, I love you more than beans and rice."

The photographer asks the madam what's going to become of Violet and she tells him Violet's made a lot of money and can do as she likes. He argues she's only 12 and completely alone. The madam observes that he's in love with her.

Outside, the photographer takes a picture of woman in a white body stocking with chickens. Jealous, Violet intrudes and stands before the woman. She wants her picture taken. "You're stupid and old!" she cries out to the photographer when she's told to go away. Girlishly, she chases after chickens. She then starts pressing herself on boys about her age who have been childhood friends, demanding them to have sex with her and prove they know how. One of them is the son of the Black cook. She comes storming in and tells Violet that white and colored can't be together and orders her to leave Nonny alone. Madam Nell has Violet whipped. "You can't beat a child. It only teaches her to beat others," the photographer tells Nell. She says she'll run her business and he can run his.

So, Malle, takes this opportunity in the script to have Bellocq object to physical violence against Violet, who he acknowledges is a child, but he has not objected to her being prostituted.

Offended at having been beaten, Violet runs away and goes to the photographer's home. Malle shows us the first floor and the photographer's dark room. The photographer then shows Violet upstairs to his bedroom which is locked. She is astonished at its being locked and asks why. He says because sometimes children break in, the neighborhood has gone bad, maybe because of the whorehouses.

Malle seems to be referring to Violet, who is from a whorehouse. But we are also reminded of how the night Violet first had intercourse, the customer who had purchased her had objected to a lock not being on the door. This is a nod to how the real life Bellocq may have had had a thing about guarding against intrusion as in some of his photos a couch is pushed up against the door and a line might be tied around the doorknob as if to secure it. He appears to be taking measures so that people can't enter a room that can't be locked. But here there seems also an intentional connection made between the customer who purchased Violet's virginity and Bellocq.

Pleased with the appearance of his apartment, Violet jumps on his bed and accidentally breaks it. Can she stay? Yes. Will he sleep with her and take care of her? No. She demands why, and he tells her he's not sure exactly .She says he's afraid of her. She wants him to be her lover and buy her stockings and clothes. He can be her fancy man. She then accuses him of loving her mother more than her, women know these theings. He says "Some men are different. I'm different. Well, maybe not after all, because...I'm all yours, Violet." She wants to know what's wrong with whores anyway--she's filling out soon, and all the men like her. Doesn't he like her? Bellocq embraces and kisses her (in such a way that it's hidden from the camera and thus need not be a real kiss between the actors)

It's intimated the pair make love.

Malle shows us VIolet's naked back as she wakes up. She finds that Bellocq has left a meal and note for her. Unable to read, she puts the note to the side. While he is gone, she looks at his books which have head portraits of glamorous women in them.

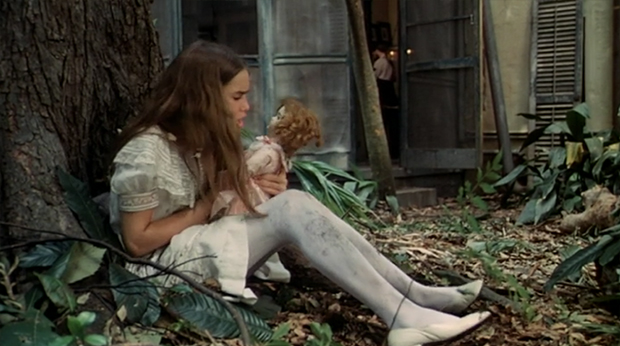

When he returns it's with a blue box, a present, which she excitedly opens. They have just slept together, and she might expect this to be a nice piece of clothing for her. Her mother once received emerald earrings! Instead, she finds a doll, and though she actually appears pleased as a child might be pleased who had never owned a doll, she is also taken aback and asks him why he brought her a doll as a present. "Every child should have a doll," he replies, asserting her childhood. She asks, surprised, "I'm a child to you?"

In the next scene he takes pictures of her as a child, in childish clothes, with the doll. Becoming bored, she chases a lizard, then petulantly takes her seat again so the photography session can continue.

In the evening, we see Violet paring her toenails. The photographer, in the dark room, calls to her but she doesn't respond. She's at the gate watching people passing by. Standing behind the bars of the gate she looks like a prisoner kept away from normal life.

I'm reminded of how Alice, in Alice in Wonderland, grows and shrinks and grows and shrinks. Sometimes she's grown so tall (as if to an adult size), her feet are alarmingly distant from her. Then she grows small again. At one point the white rabbit calls to her to get some things for him from his house. She goes into it and, upstairs, takes a drink from a bottle and grows large. The lizard, Bill, is sent in to try to deal with the situation somehow, but when he tries descending the chimney Alice kicks him away. Finding a cake she eats it, grows small again and slips out of the house.

Violet sits alone in the garden in her child's dress and white stockings and shoes, but the stockings are by now soiled with dirt. Holding the doll, she angrily berates it,"Violet what ails you? I'm talking to you!" She hits the doll. "I've got such a splitting headache. You're so selfish Violet, everyone gets to do what they want except me." The photographer comes out to ask if she knows what has happened to his silver nitrate. She confesses she poured it out in order to play with the bottles. He scolds her for wasting expensive chemicals. She cries.

Bellocq watches Violet bathe. Then in the next scene, Violet lies on a couch, posed nude for a photograph--and Malle has has elected to go with fully frontal nudity for the shot. Violet protests lying there for too long and Bellocq becomes upset with her. They argue. "I'm tired of having to deal with a child," he says. She replies that she doesn't need to be with someone who yells at her and says she's going to leave. She breaks one of his negative plates, and then scratches out the face of another, which is a nod to the mystery of how some of the real life Bellocq's plates have the face scratched out (it's known now Bellocq did this on fresh emulsion, and not his Jesuit brother). When the photographer sees what she's doing and approaches, she breaks the plate. He slaps her, and yells, "So this is how you would repay me! Get out before I kill you." She says no one cares about his pictures as she flees. He locks her out of his room, nude. She cries.

People are protesting the brothel with signs such as "Sin Stinks" as Violet walks up dressed in one of Bellocq's shirts. Inside she finds disarray. Madame Nell burns money. "Death is keeping them away," she says of the johns (which seems to anticipate the pandemic of 1918, which would likely have shut down the business anyway), but it is 1917 and what is happening is the red light district is being shut down. The day the furniture is emptied out, the denizens gather outside with their bags, each to go their own separate ways. Some are going to Chicago. Where will VIolet go, who has no address for her mother? Out of the blue, the photographer shows up and says he will marry her.

The newly married couple and some of Nell's friends from the brothel take a drive to go on a picnic, singing, "Billie Boy". "She's a young thing and cannot leave her mother." The car gets stuck in a swamp when they're turning around and the women take off their clothing in order for it not to be ruined by the mud. A barge passes by on the river, and several men leap off it to swim ashore and take part in the picnic with these women who are only in their underclothes. Alice proudly stands up and announces it's a wedding party and guess who the photographer married! The men pay no attention to the child, excited by and only attentive to the women in the party. It's a pathetic scene. She may be old enough, at 12, to have been married, but she's a little girl.

Somehow, somewhere, in this depiction of the wedding picnic, is likely something to do with Charles Dodgson's rowing trip down the river to the picnic with Alice Liddell where Alice in Wonderland purportedly had its source. It was another such trip that immediately preceded the disruption of the relationship with the Liddells, some questioning if Charles had suggested to the Liddells he wanted to marry Alice, and I wonder if Malle is referring to that story as shortly thereafter Hattie shows up, declares there is no marriage as she didn't give permission, and carries Violet away to St. Louis.

Next we see the pair, they've been married two weeks. Bellocq sits and watches Violet as she carefully lathers butter on a pastry. In a demanding manner, she rings a bell, and we see they have employed a maid. She declares she's feeling poorly today and wants hot chocolate with brandy in it. She's going to sleep all day. Either she has begun menstruating and is on her period, or she is behaving as if she has been with a john, which is work for her, and the reward is to take it easy, as would the prostitutes at the brothel, and have a servant attend to her. Bellocq asks if she knows how to prevent having children, and she insists she does, that she knows about these things. At this point, her mother, Hattie, appears, with Will and her new husband (Hattie obviously did not know how to prevent having children). She says she told the husband about Violet and he insisted they come get her and take her to St. Louis. "Papa and I are married now," Violet says, but Hattie tells her that has been fixed as it can't have been done without her consent. Bellocq objects, saying Hattie deserted Violet. But the plan now is to send Violet to school and raise her right.

"I can't live without her," Bellocq says. Violet, however, wants to go. She proposes, "Papa you can come with us," but this is, of course, impossible. Without any real sense of consternation, Violet leaves, urged not to take the time to pack her things. They will buy her all new clothes.

In the next shot, VIolet is at the train station with her family, dressed as a child with a big plaid bow in her hair. Her new father, Mr. Fuller, takes a photo of Hattie with Will and Violet. As they ready themselves for a second shot, Violet gazes into the camera held by new father and we reflect on how her association with the camera will be the photographer, Papa, and posing for provocative images. We all must know that things will be troubled for the girl in the future, in St. Louis, but...is that the message here or not? I have heard too many times, Malle, in interviews, relate how the original Violet, despite her early life in Storyville, entered respectable society and became a respectable, suburban mother, and Malle has remarked on how it's now time for the child to grow up, she's going to take her place in bourgeoise society and live a respectable life.

In the interview with Studs Terkl, Studs, based on Malle's observations, expresses how this is a film in which the child feels no shame, there is no sense of sin, that this is an anti-Puritan film, and curiously asks what happens to the Violet upon whom the film is based. Did she find respectability, which is what Hattie wanted? Malle replies yes, but what's so great about her is she didn't feel bad about it, he was touched that she has no guilt, it was a strong moral attitude, and though it might shock a lot of people he believed it was the right moral attitude.

Gene Siskel participating, asked, however, about her anger. Where was that? Didn't she have the right to feel angry about what had been done to her?

Malle, confused, asked if Siskel meant the child in the movie or the woman upon whom the story was purportedly based.

Gene said he was asking about the real woman.

"Do you mean she should be angry?" Malle asked.

Gene said, "Yes, because she didn't have a choice."

To which Malle responded, "Well, yes, but, you know, the way she's raised, there's another interesting scene and let me tell about that and that might answer your question. There's one scene later on in the picture where she's fooling around, she's kind of cross because she's trying to seduce Bellocq and Bellocq doesn't want to photograph her, and that's taking place outside in the back yard of the house, and she gets into sort of a barn, and there's a little boy there, Black, he's the son of the cook, and she starts aggressing him sexually, they play games and finally she pushes him, she tells him, I'm going to love you now and you're going to see how good it is, and then the mother of the boy, the Black woman, the cook, comes in and she teaches Violet a lesson because Violet doesn't know and Violet says why shouldn't I do it with Nonny, everybody does it with everybody, And then the cook says wait a minute, you don't know nothing about the real world, you've never seen Black people going upstairs in this house and it's not the way it works, and she has to learn the lesson, and she gets a good spanking in order to learn that lesson."

Malle, who has stressed that the original Violet went on to live a respectable life, completely avoids answering how Violet might know she has been abused and feel angry. He denies her the right to feel any trauma, by way of insisting she didn't know any better. It is interesting, because in the film, he permits her to be enraged when she is whipped. She knows it is wrong to be beaten. But Malle insists that Violet has been raised in a situation in which anything goes, so she has no idea of "sin", and has no feelings of guilt. In accord with this, he seems to be implying that Violet can't feel anger about her upbringing as she has no idea it was wrong, it was simply normal to her.

But one of the reads one can have on the scene in which Violet pressures the boy to have sex, is not just that she's not supposed to have sex with a Black individual, but that she is actually taking out her sexual abuse on others, for she behaves angrily, refusing to honor boundaries, bullying.

As the conversation moves along, Gene attempts, again, to pin down Malle and get an answer from him. Gene says we all know that child prostitution is still ongoing, Malle has made a very modern film, but says he thinks people still want to know his attitude toward it. How can he "assure people you're not part of the whole game yourself? Maybe people can only do that if they see the film themselves. But aren't you exploiting too in some way? And this is the one issue."

Malle replies, "Well, you know, it's a picture about exploitation, and I don't think it's an exploitation picture, but of course it's a thin line and I'm quite aware of it, because my point is, I certainly don't deny that I'm part of it, but I want audiences to understand that everybody's part of it. We're all part of it. We're in a society that's cheating and lying and playing with values, and pretending to be something and actually being something else, and we all know that if we try to be a little honest. But usually people don't want to cope with it, they try to pretend it has nothing to do with them. You could say it about lots of things. You could say it about the Germans after the war said they knew nothing about concentration camps. They knew everything about the concentration camps. But there was a..it's a very extreme example but still I'm interested in bringing people to feel that there's no way to be innocent, there's no such thing as integrity, the moment you're part of a society you're entirely responsible for everything that's wrong with it." He later calls it the hypocrisy of everyone.

Studs brings up the casualness of the girl and how in Lacombe Lucienne the character so easily comes to fascism. Everyone has the potential of being a monster. They discuss Murmur of the Heart and how it is about incest but is a comedy, and Malle relates how people would come out of the theater laughing and do a double-take about what they'd just seen because they were laughing about it.

Later, Malle says his comment, his interpretation, what he has to say about it is in the way he films it, that the message isn't by means of dialogue or anything rhetorical. Gene asks for an example. Malle remarks on how the piano player's face during the auction scene is a commentary on the horror of it (so he does call it a horror). Studs adds that the photographer is capturing the beauty there, the woman revealed, which one would only find in 1917 in the cat house. Malle responds, "I must tell you right away I felt very close to Bellocq, and the more I worked on the script and during the shooting I felt that Bellocq was a little bit sometimes like what we film directors are, and I was trying to portrait an artist with the obsession of grasping moments, sort of fixing moments of time, pieces, like something in the face of a woman, and that's what we're trying to do. We're trying to get some of these moments and piece them together and they're a film. And there's one scene, for instance, when Bellocq is photographing the girl's mother, Hattie, and it's the middle of the afternoon, and I've tried to suggest that it was very hot and the light is very important, and it's kind of a very sensual moment in the film. And Bellocq is just kind of transported because he's moving her, placing her, and he keeps talking to her the way we film directors talk to actors. Oh,you're beautiful, you're fine, it's great, don't move, and then he takes the shot and he says it's great, I'm so happy now. You know, RIchard Avedon saw the picture, he saw it twice actually, and he told me that he loved it, and he told me there's one line in the picture that I love, it's when the photographer says I'm so happy now. Which is just the moment when--and, of course, you're basically unhappy, but there are those moments when you know you've been catching something. And that's what it's all about, and it's the same thing being a painter."

Gene again tries to pin Malle down on his feelings about the subject matter. He says, "Are you criticizing that photographer in a way--he wants to make it seem a lot nicer than it may really have been. That's a very beautiful photograph of that woman. You might not know the abuse, the high death rate, the physical destruction, the disease in that photograph. I don't know if you can see it in his photographs. And I might ask the same of you? Do you think that you have made, like his photographs, a very sunny, lovely film about a world that may have been a lot rougher and a lot more violent. When Studs walked out of the movie theater...he said it's certainly a lovely (sunny) world. What do you think about that?"

Malle replies, "Well, i think that's just the way it works. You're always trying to catch something that's better than life. I mean, we all have that kind of idealism, but the process of making it happen, I think in the picture you have a good chance to see that there's all kinds of very grim aspects in that life. I mean, after all, Bellocq is not innocent. He's a man that's very much of a child, he's very, superficially you could think of him as being innocent, naive, sort of the artist who doesn't know about the real world, but if you think of it he's exploiting Violet." He discusses how he buys her the doll then takes photographs of her with it in costume. "Consciously or unconsciously he had in mind he would use that doll, and he had this fantasy of photographing her with the doll, so I'm trying to show that Bellocq too is part of the exploitation, and I do believe that I too am part of the same exploitation."

I'm still uncomfortable with this, though Malle has finally said Bellocq is exploiting Violet. Malle does not say, however, that Bellocq is sexually abusing Violet. He says that Bellocq has exploited her through photographing her--like he, too, Malle, exploits people by making films using their image.

Studs says many aspects come out about the degradation but it's done in such a sunny way. He asks if Bellocq romanticized the life of the prostitutes in their posh environment. Malle says there were lower class prostitutes and he could have made it a picture about them, so it was a matter of choice making it about the better brothels. "...since in the real story it was taking place in one of those (expensive) houses I chose to stay with the real story...but I want to say something, somebody came out of a screening and told me you know talking about the auction scene it would have been a lot easier if everything was not that beautiful, and the little girl is so stunning looking, so it makes it even worse. And I thought about that, I felt it's presented like something very glamorous makes the other side of it even worse. "

Gene asks, "If you show that everyone is responsible, doesn't that contain a message that maybe you should stop making films, we should stop interviewing you about your films, and that we should all get out in the streets and tear down the houses of prostitution...is that the logical extension of what you're saying?"

Malle replies, "Well, but then we have a lot more to do. We should totally change that society, and uh then you have to start a revolution right away and--a few months ago I was in France and I read a piece in a French paper about child prostitution existed in USSR, which I found terribly interesting, and they also have the same problem." Malle then goes on to speak about a documentary he made on a car factory, and how it must seem horrible to do the same repetitive thing all day, every day, for years, and that's how many people felt about it, watching the documentary, but he spoke to the workers and they were comfortable with it and their lives, making more money than they had before, so he says it's all contradictory and he himself can't sort out the contradictions.

In other words, how bad can Violet's life have been if she didn't know it was bad because she was brought up to think it was normal, and she made good money. At the same time, yeah, it's bad. But, no, it's not bad if you don't know others think it's a bad thing.

From an interview with Andrew Horton, an Assistant Professor of English at the University of New Orleans, and Peter Britton, a freelance writer-photographer in New York:

HORTON: - Your vision of a New Orleans whorehouse in 1917 is spoken of by Vincent Canby as a non-romantic kind of "romanticism." You de-emphasize sexuality and brutality in order to present "sin" as "exquisite," as you say, or simply quite ordinary. What would you say to those critics who complain that you have left out the seedy side of prostitution?

MALLE- I'm not really quite aware of that. People seem to have been totally taken by the photography. By the way, one amusing aspect of the photography is that Sven Nykvist did not actually film all of the scenes. I just read one critic who writes, "Again Nykvist takes over for the filming of the picnic scene," but Sven wasn't there to shoot the picnic scene! That is nice! Sven is such a great artist he does not even have to be near me! But the photography in this film is not flashy. For instance, Sven practically never used back-lighting in the film. Which is unusual, especially for a period film. And the set is remarkable, but it's not the usual image of a whorehouse. Usually you think of colors such as red and gold, which are richer. But we tried to tone down the colors. I don't know. I don't see that the film is so visually stylized myself. Again I would say that I didn't really mean to do it in such a way. I guess I could have shown more squalor but it just didn't happen that way. There are, however, one or two moments when you have a feeling of it. But basically I felt that, dealing with that subject and theme, it might be more disturbing if everything looked so easy and so nice. One American friend saw it before it was finished and said she found the film particularly terrible and beautiful and seductive at the same time. That's what I wanted people to feel. I don't think it would have helped to show more rats. I love to show rats because I love rats, but they didn't need to be in this film.

HORTON - ...Bellocq, he is so elusive as a character, and yet his relationship with Violet is touching.

MALLE - I must tell you something about the Bellocq-Violet relationship. When I was shooting the picture I suddenly felt the little I knew of Bellocq was me. There was a part I could identify with. And I got to identify with him very, very much. Especially as the character was played by Keith Carradine, but of course it goes both ways because I also felt close to Keith. There was something in him I responded to, and I had been considering lots of other actors. We were very much like brothers. We had a kind of intimate communication. And I felt in the middle of shooting, especially during those difficult scenes in Bellocq's house where Violet is supposed to come and stay with him - I started asking myself, if I had been Bellocq and considering that Bellocq was not terribly interested in sex, you could very well imagine the relationship without sex. Which probably would have been my attitude. After all, this child is a child. That would definitely be my interpretation. If you used your imagination you could imagine a lot of things taking place between them. But obviously this big sexual fantasy, hang-up, of the child molesters who enjoy child prostitution or child pornography has to do with the fantasy of incest and perhaps also the fantasy of rape: there's something violent about it. It's about penetration; it's brutal. And it's repressed. But it seems to be such a strong fantasy that I think that's why it's so big today in this country, for instance. But you can also imagine another kind of relationship between a child and an adult, one like Violet's and Bellocq's.

And in this relation I must tell you that I thought a lot about Lewis Carroll. He was a fascinating man who used to photograph nude little girls, pictures that have been published. He was a clergyman but I have no idea what was going through his mind! Yet he never did anything. He was just interested in little girls, and so he wrote Alice in Wonderland. But his photographs are remarkable. This fascination with children is something I certainly share. You could say that the human body starts decaying at the age of sixteen. There is nothing more moving or beautiful than the body of a child. It's one of the things I find fascinating with my own children, for instance. I always feel like hugging them and touching them because they are so .... But I have so many troubles with such a film because people talk about nudity. For me, nudity is not taboo because it is not obscene. But a lot of people bring in their own fantasies, and that's why they get so emotional and outraged. I see it completely differently.

Source: "Creating a Reality that Doesn't Exist": An Interview with Louis Malle Author(s): Andrew Horton and Louis Malle Source: Literature/Film Quarterly, Vol. 7, No. 2 (1979), pp. 86-98 Published by: Salisbury University

What in the world is Malle talking about here? He says he came to identify with Bellocq, and imagined what he would do as Bellocq, and talks about how Bellocq wasn't interested in sex, and how he can imagine the relationship without sex. He says people imagine things (sex) taking place between Violet and Bellocq, but that is fantasy and violent, about rape, "But you can can also imagine another kind of relationship between a child and an adult, one like Violet's and Bellocq's."

But in Malle's film, Bellocq is sexually interested in Violet! He has sex with her! Malle makes it look like Violet seduces him, and it seems Malle may be comfortable doing this because he can plead Violet has been taught all this, the art of seduction, by working in a brothel and so does not know any better, that she is someone without any sense of "sin" or shame. That may be why he is so insistent that Violet not feel any anger over the abuse, because he must have her absolutely unaware of any abuse taking place. Malle, actually, thus places all the responsibility on Violet for the sexual relationship with Bellocq, so that it can be said that Bellocq bears no blame, that he is ultimately sexually disinterested. Yet Bellocq is interested in Violet and has been from the beginning. Malle's excusing of Bellocq even goes into Lewis Carroll territory, he insisting that Carroll, though he was interested in girls, and took erotic photographs of them, never did anything with them. He compares Bellocq to Lewis Carroll.

Malle! Your character, the one you wrote, a person who didn't exist (no one knows anything about the real sex life or interests of the historical Bellocq, other than the fact he was a commercial photographer who took also photos of adult prostitutes) had sex with the 12-year-old girl! What are you talking about? Your character had sex with her. Aren't you aware of this? He took erotic photos of her and had sex with her!

MALLE - ...if you’re Violet who is raised in a whorehouse and knows very little about the world outside . . . Her experience of the world comes from what she sees in the house. She sees men who are like objects— she has no relationship with them because they come for something very precise, they’re completely anonymous. The Johns, the customers, don’t really exist. So, Violet is left with the men in the house with whom she can have a relationship— the two outsiders: the piano player who is black, as most of them were, who is very lucid, watching the scene with a lot of irony — his presence itself is a comment. During the auction scene, there is a very long shot of him and you can imagine all kinds of things going through his mind. Bellocq is also an outsider and is the one man the girls can relate to because he’s different— he’s not looking for sex, he’s not a John, and he becomes a friend: he’s a human being, not someone who’s going to “lie on top of you,” as one of the girls says.

Source: Louis Malle: An Interview from "The Lovers to Pretty Baby" Dan Yakir; Louis Malle. Film Quarterly, Vol. 31, No. 4. (Summer, 1978), pp. 2-10.

Again, Malle, don't you know your own film?! Bellocq has sex with Violet! When she asks him, early in the film, why he doesn't go upstairs with the other women and have sex with them, he tells her, "That's for me to know and you to find out." Bellocq has sex, he just eventually has sex with Violet, who he has groomed, who Malle makes into the child seductress who bears no guilt because she doesn't know any better, and somehow Bellocq manages to have sex with her without the director really admitted to him having sex with her.

It's exploitation. It purports not to be exploitation, but Malle shows in his interviews that his interest is in Violet being the child who can can innocently seduce because she has no sense of "sin" or shame, and Bellocq is a Lewis Carroll like character who does exploit her, like, Louis Malle, in that he takes pictures of her, but otherwise he has a good, non-sexual relationship with Violet. Despite the fact Bellocq has sex with Violet, somehow Louis Malle wants to convince himself and everyone that he doesn't. Which is the conflict I felt in the film, watching it. I felt this conflict in Keith Carradine's portrayal, and I wondered if it was coming from him, his discomfort of working with a child, or if it was instead a problem concerning Louis Malle. It appears to have been a problem with Malle, who defends Carroll's erotic portraiture of young girls, while insisting that Dodgson couldn't have done anything with young girls as he wasn't sexually interested in them, and he transfers this to his character, Bellocq, insisting he may take photographs, yes, but he has no sexual interest, therefore Violet is safe with him, therefore Violet and he have this special relationship.

This is the problem with Pretty Baby. It says it is one thing, but is another thing altogether. It is just again another tale of the victim-child made into the aggressor, seducing an "innocent" and naive man. These are not my words. This is what can absolutely be drawn from the interviews with Malle.