Return to Table of Contents for films

The past few days I decided to give a closer reading of Joan Lindsay's Picnic at Hanging Rock. Though my focus will be on the book, I'm placing this under film analysis as, by now, the book and film have become hardbound companion pieces. Not that it isn't easy to ignore the film and focus entirely on the book, but I consider the book to be essential reading in respect of the film.

To compare the book with the film and what they have produced separately and together is complicated by the fact that there exist actually two books. One is the book that Joan originally wrote, and then there is the book that was published, the editor having concluded it was best to excise the last chapter. The 18th chapter.

We run into problems when we take Lindsay's omitted 18th chapter into consideration, which was only released after her death. Do we include it in our study or are we also to omit it?

Below are the main section links of the analysis:

The 18th Chapter--How it is Both Essential and Not

The Problem of Hesperus and the Confusion of Longfellow's "The Wreck of the Hesperus" with Hemans' "Casabianca"

The Frenzied Attack on Irma Leopold

The Puzzle of the Pythagorean Theorem

and the Hypotenuse as a Way Home

Nietzsche's Monolith and the Eternal Recurrence

The Walkabout

Weir's Depiction of the Ascents of the Rock Compared with the Book, and the Wounding of Michael and Irma

The Problem of Irma

Miranda and Metamorphosis, The Butterfly and the Crab, The Beautiful and the Absurd

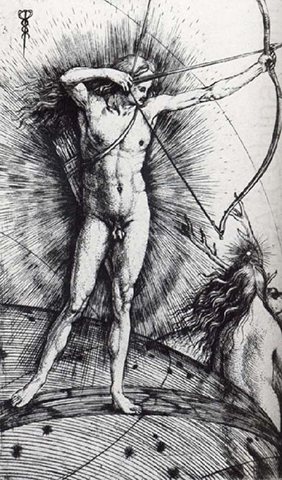

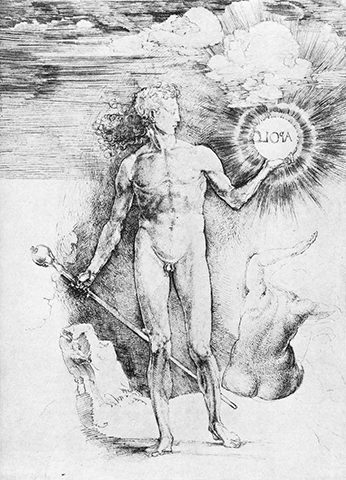

Daphne and Apollo-Python

On Spelling and Emeralds and the Demand to Forget

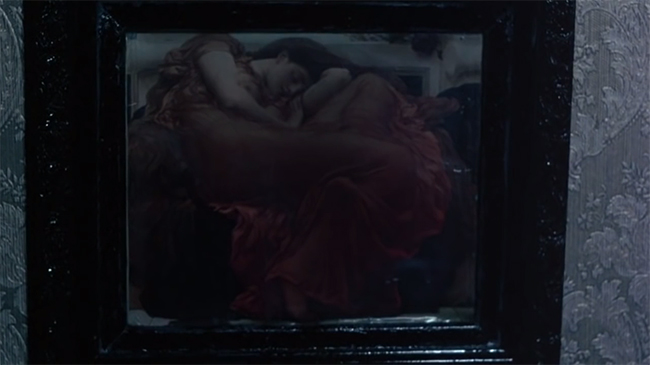

The Connection of Appleyard to Hanging Rock -- Ascents, The Watcher on the Hill, Flaming June, Sara Waybourne and Bournemouth, the Hanged Man

The Marie Celeste, The Spider and its Web,

and the Clever Embroidery of Irma

Leda and the Swan and The Marquise of O

The Plot of The Marquise of O

Possible Relationship to Picnic at Hanging Rock

In brief, the plot concerns a group of Victorian teenage girls, Miranda, Marion, Irma and Edith, students at Appleyard, an Australian boarding school, who climb a great ancient rock during a Valentine's Day school outing, their schoolmates preferring to rest at its base. As they ascend, Edith, the only girl who has complained with the exertion, begins to consider her friends are behaving peculiarly. She becomes so alarmed she runs, screaming, back down the rock. The rest of the group disappears, never to be seen again, except for Irma, who is found unconscious days later. Lindsay's book, and Weir's film, explore the happenings preceding the ascent, the desperate search for the girls, and the effect of the mysterious disappearance on the school, two teen boys who had seen the girls as they began their ascent, and Sara, a girl who had not been permitted to go on the outing, and who we may interpret as having been in love with Miranda and/or profoundly attached to her as she is an orphan and Miranda has been her refuge of kindness in an otherwise bitter world. In the published book, as with the film, we never learn what has happened to the girls or a math teacher, Miss. McCraw, who had also climbed the rock.

The unpublished 18th chapter of Lindsay's book concerns what occurs after Edith runs away. The girls are all, with the exception of Irma, affected by a natural "monolith" they find on the rock, which so powerfully, magnetically attracts them that it causes them to feel they are turned "inside out". They pass behind the monolith and fall into their deep sleep. When Miranda wakes she sees a brown snake. Miss McCraw now clambers up. She is unrecognizable to them, just as they are to her, but no doubt she has pursued them because of her concern for them, she was their teacher and she will be their teacher to the end, through this transition from one state of being to another, instructing them on what is occurring. She has already stripped down to her core essence in a way that her pupils are still yet moving toward perhaps because the girls traveled up the rock together rather than making a solitary journey, as has Miss McCraw. Though each retains the essence of their personality, their connections to culture and past have entirely evaporated, they wholly concerned with the present moment. They throw their inhibiting corsets over the cliff and see them "stuck" in time. The group is now forever at high noon, a place of no shadows, of all light. They realize that they will "arrive in the light", and though they don't say where they will be arriving you know it won't be on the wagon heading back to Appleyard with the other girls. McCraw sees then what she has sought for all her life in a hole that is positive space rather than a void.

It wasn't a hole in the rocks, nor a hole in the ground. It was a hole in space. About the size of a fully rounded summer moon, coming and going. She saw it as painters and sculptors saw a hole, as a thing in itself, giving shape and significance to other shapes. As a presence, not an absence--a concrete affirmation of truth. She felt that she could go on looking at it forever in wonder and delight, from above, from below, from the other side. It was as solid as the globe, as transparent as an air-bubble. An opening, easily passed through, and yet not concave at all.

A snake appears, lying next a crack in the ground beside two enormous boulders, one balanced atop the other. Miranda touches the "exquisitely patterned" scales of the snake and it slithers away behind some vines. Tearing away the vines they find a hole in the ground and understand they are to follow. McCraw does so first, she saying that when she is inside and the girls hear a rap in the rock then the next is to follow. Becoming a crab, she flattens herself upon the ground and is thus able to slip through the narrow opening in the rock. When a rap is heard, Marion follows next, similarly flattening herself. With the next rap, Miranda enters. No rap follows for Irma, which is something I will write upon later, the reason for why this is. The hanging rock tumbles over the hole into which the three have disappeared. This doesn't answer as to why no tracks or clothing are found on the rock (perhaps because these things are all stuck in "time" as are the corsets) but it does explain why the girls and McCraw are never found.

My thoughts on the excised 18th chapter are that, though Lindsay was a proponent of letting people draw their own conclusions on the mystery presented in the book as it was published--and I don't imagine this was only a matter of not wanting to conflict with editor's choice and the film's mystery Lindsay--she also did intend the 18th chapter to be eventually leaked, that she didn't want her original ideas lost, but also that the book came, for her, to have two endings. The 18th chapter does not, as some state, lessen the mystery of what happens to Miranda, Marion and Miss McCraw, but it does limit the grounds of the mystery to the interaction of these individuals with the rock, which actually should be the conclusion reached in both the book, as it was published, and the film. Albert and Michael, the two boys who had seen the girls and briefly followed them, are quickly cleared of playing any part in the disappearances. This is not a murder mystery. It is partly an exploration of cultural conflict and the impact of Australia on the children of England imported there. The rock is indigenous Australia as versus Victorian colonialism and Victorian spirituality, and the effects of that time nearly three-quarters of a century on, for this was certainly a book and film of the 1960s and 1970s. The 18th chapter does formally weaken the book, at least as it was released. The writing is not as good. It wasn't finessed. What we have is probably an early draft. But the 18th chapter, so jarring as to be untenable for most readers, is also an important addendum that even further transports the material away from a romance. In support of her editor's decision, and then the mystery as established by the film, Lindsay probably didn't mind becoming a proponent of letting people draw their own conclusions as she believed without that chapter there was enough in the book, and film, to point people toward some version of a mystical conclusion, if not exactly. Not at all exactly (for who would imagine Greta McCraw metamorphosing into a crab). But it didn't need to be exact. Still, she did not destroy that chapter and room was made for it to emerge after her death, in all its seeming ridiculousness, the fantastic absurdity of the fates of the disappeared being so unanticipated by the sensibilities of the majority that the 18th chapter in itself would be even more mysterious for them than the book as it stands. In turn, Joan, the writer, appears absurd, even comical, with her conclusion as most receive it as beyond bizarre. Would Joan have minded appearing absurd? I doubt it. She certainly didn't mind appearing absurd after her death when she would be unable to defend the chapter. Joan didn't want what had happened to her characters to be lost; she desired those who searched to have something to find and ponder. But I imagine she also didn't want that 18th chapter to detract from what was most important, that the Victorian empire was no match for the rock, that not everything was explainable according to Victorian or contemporary Anglican perceptions, and that the ripples from the occurrence at the rock reached in all directions with unforeseen consequences. And by the occurrence at the rock, I think this also came to mean the book and the film. Inarguably, one of the mysteries of the rock was that Joan's fiction of what occurred there to all these characters became "real", many believing the story was based on a real happening, such was the strength and truth of the myth.

Now I know.

What do you know?

I know that Miranda is a Botticelli angel.

The French governess remarks on Miranda being a Botticelli angel, but instead we're very aware she's referring to the birth of Botticelli's Venus. This occurs as Miranda turns to wave good-bye as she goes to ascend the rock with the other girls, and even though she has promised they will not be gone long exploring the rock, as the audience who is aware the girls will disappear we see finality in that wave. In the book, the governess doesn't voice out loud what she now "knows" as she does in the film, which is love, for she sees in Miranda not death but the birth of Venus as she rides upon the waves onto the beach, emerging from the ocean. This birth or solidification of love occurs for several characters as a result of the disappearance, while for Sara the disappearance of Miranda is disastrous, as well for the cruelly unempathetic Mrs. Appleyard, the school's owner and director, her institution appropriately destroyed.

In the opening chapter, it's Sara Waybourne's failure to learn Longfellow's "The Wreck of the Hesperus" that causes her, of all the girls, to be denied, at the last minute, participating in the trip to Hanging Rock (location 165 in the Kindle version). This makes one wonder, also, what would have happened if she had been permitted to go, and Joan perhaps had ideas about that.

Hesperus is the evening star, the half-brother of Phosphorus, the morning star--these brothers conceived of by the Greeks when it was believed that the two planets were distinct from one another, then when understood they were one in the same they were dedicated to Venus.

While Miranda and her fellows are at Hanging Rock, back at Appleyard College Mrs. Appleyard tests Sara, expecting her to have learned her lines by heart by now. Sara protests she can't learn the poem as it's silly.

Appleyard. The name conjures visions of Eden, its serpent, the tree of knowledge, and the ejection from the garden, does it not?

"...You little ignoramus! Evidently you don't know that Mrs. Felicia Hemans is considered one of the finest of our English poets."

Sara scowled her disbelief of Mrs. Hemans' genius. An obstinate difficult child. "I know another bit of poetry by heart. It has ever so many verses. Much more than 'The Hesperus'. Would that do?"

"Hhm...What is this poem called?"

"An Ode to Saint Valentine". For a moment the little pointed face brightened; looked almost pretty.

"I am not acquainted with it," said the Headmistress, with due caution. (One couldn't in her position be too careful; so many quotations turned out to be Tennyson or Shakespeare.) "Where did you find it, Sara--this, er, Ode?"

"I didn't find it. I wrote it."

"You wrote it? No, I don't wish to hear it, thank you. Strange as it may seem, I prefer Mrs. Hemans'."

Location 558 in the Kindle version.

Joan, of course, knows that Hesperus is Venus. While the College, that evening, awaits the return of the girls from the rock, Joan even includes "Venus" in the action, pairing the happening at the rock with the only specific mention of "Venus" in the book.

...Minnie had lighted the lamps on the cedar staircase where Venus, with one hand strategically placed upon her marble belly, gazed through the landing window at her namesake pendant above the dim lawns.

It is just after 8 o'clock, when the carriage was to return from Hanging Rock, but it hasn't.

Some take it that Mrs. Appleyard's inadequate knowledge of English literature is being betrayed here and becomes the focus, she confusing Felicia Hemans' "Casabianca" with "The Wreck of the Hesperus". But, in the meanwhile, Felicia Hemans' "Casabianca" is spoken of during the climb up Hanging Rock (location 490 in the Kindle version). Miranda, Marion, Irma and Edith are resting in preparation for walking back down to the luncheon--they still plan on returning to their friends and the college, the dream time of the rock has yet to capture them. While they rest, Edith critically divulges that Sara writes poetry about Miranda. Irma replies, "Poor little Sara, I don't believe she loves anyone in the world except you, Miranda." To which Miranda defends Sara's love for her, informing the others Sara's an orphan, a revelation we later learn is a betrayal of Sara's trust, for Sara had only informed Miranda of this fact as she seems to be ashamed of her time spent in an orphanage and being unlike the other girls in not having a family. When Irma compares Sara to a "doomed" deer she'd once tended, and Edith questions her what she means, Irma replies with the first line from Hemans' "Casabianca".

"Doomed to die, of course! Like that boy who stood on the burning deck, whence all but he had fled, tra...la la...I forget the rest of it."

Like Sara, Irma has difficulty remembering poetry. That she here voices she "forgets" the rest of that poem is to be remembered later when she is unable to recover any memory at all of what happened upon the rock.

So the story of the memorization of a poem becomes a little more complicated than at first glance. We know from the exposition that Sara (and likely her classmates) was supposed to learn Longfellow's "The Wreck of the Hesperus", a poem about a girl doomed to die on a sinking ship, tied to the mast by her father in order to preserve her during a storm, then her father perishes before her and is unable to release her from the bonds which may or may not have destroyed her. It is a story of the father's hubris, for he was warned against taking his daughter on the ship, he was warned about the storm, but he had faith in himself as the sure captain of his ship, his destiny, and his daughter's life. It is also a poem that was inspired by a real life event, an 1839 blizzard in New England that destroyed 20 ships. One of those was the Favorite on which all hands perished, as well as a woman who was afterwards found tied to a mast. There was also a different ship called Hesperus that was damaged in the same storm though docked in Boston.

During the climb up the rock, Irma compares, however, Sara to the boy who dies on the burning wreck of a warship in the Hemans' poem "Casabianca". That child was also bound to a ship, this time through loyalty to his father who dies below deck during the night and thus never releases the child from his duty. Probably about the same time as this, back at the Appleyard College, Mrs. Appleyard quizzes Sara on if she has learned the verses but misstates and says Hemans rather than Longfellow. Sara doesn't catch this, and Hemans becomes linked with "The Hesperus" for the remainder of the conversation.

And, yet, back at Hanging Rock, Irma had trouble remembering "Casabianca", so the reader must remain confused as to what poem was intended to be learned, despite Joan stating at the beginning it was "The Wreck of the Hesperus", when Appleyard remembers it as by Hemans and Irma recalls "Casabianca" in connection with Sara, whom they had just been discussing as being herself a writer of poetry.

These events and confusions are connected in an intricate way that demands more than superfluous examination.

Mrs. Appleyard, fresh to Australia, is described as a galleon, another doomed ship, and represents English colonial imposition on Australia and its tragic disregard for the native people, the land, and its history. Alienated from nature, she embodies colonialism's companion cultural mores that infected the globe like a highly contagious virus, so that photographs from 1880 Australia are, in attire, demeanor, and sensibility, indistinguishable from photos of America's Kansans. The environment is expected to be subject to colonial culture rather than the individual being subject to the environment. She is both the empire that demands loyalty to the death and the child who has wholly trusted the empire and is unable to escape it. The requirement that the girls memorize these poems (one is English, one is American) in remote Australia, all the way around the world, speaks to empire and the fierceness of its preservation so that, as if hypnotized, instructors and children around the world learned such verses by heart, carving their brains with them into a kind of English countryside and attitude that they would carry with them everywhere, an attitude expected to preserve them from contamination by their alien new home and its indigenous inhabitants.

It may be that Sara has the surname Waybourne due the saying, "He who would all England win, should at Weybourne hope begin." In other words, Waybourne was a highly vulnerable site and was thus a place of concern and peril to the entire nation if not closely safeguarded. Is it any wonder that Mrs. Appleyard then has it in for Sara and that Miss Waybourne is so imposed upon to learn her verses. Poor Sara, in her contrariness, is as the vulnerability that could destroy a world. And so even though it's the disappearances of Miranda, Marion and Miss McCraw that sink the school, that the trip to Hanging Rock is balanced with Sara's being held back at the school, she having not learned her verses, plays also a part.

There are layers upon layers, and more to the poems than this. I checked to see if Hemans had written a poem on Hesperus. And she didn't. But she did. In the poem "The Voice of Spring", she writes of the hint of spring's arrival "In the groves of the soft Hesperian clime, to the swan's wild notes by the Iceland lakes..." But as spring arrives it finds things have changed. "I see not here, all whom I saw in the vanished year. There were graceful heads with their ringlets bright...are they gone? Ye have looked on death since we last met." Spring mourns that "they have gone from amongst you, the young and fair" and goes to join those missing, abandoning those left behind as they "...are marked by care, ye are mine no more, I go where the loved who have left you dwell..."

By the time Easter arrives, disaster will be fully upon Appleyard College due the disappearance and presumed deaths of the girls and Miss McCraw. My contention is "The Voice of Spring" is referred to with the confusion of Hemans and Longfellow, Hemans becoming the writer of "The Hesperus", for "The Voice of Spring" foreshadows the disappearance of the girls and Miss McCraw. Also, in the poem the mention of Hesperus is directly followed by the image of the swan, and Miranda is consistently associated with a swan in both the book and the film. When Michael, also fresh to Australia, sees Miranda crossing a stream, she seems as through a graceful swan. Repeatedly in the novel she returns to him as a swan, which was sacred to both Aphrodite and Apollo, Aphrodite sometimes depicted as riding a swan-chariot.

Curiously, a book of poetry published in 1904 unites Hemans and Longfellow. The World's Best Poetry, edited by Carmen Bliss, has on page 184-186 Hemans' poem "Casabianca". The author's name is at the end of the poem, then directly following the name "Felicia Hemans", on page 186, is "The Wreck of the Hesperus". Just a fun little coincidence I enjoyed coming across and made me wonder if Joan's hands had ever come across the same volume.

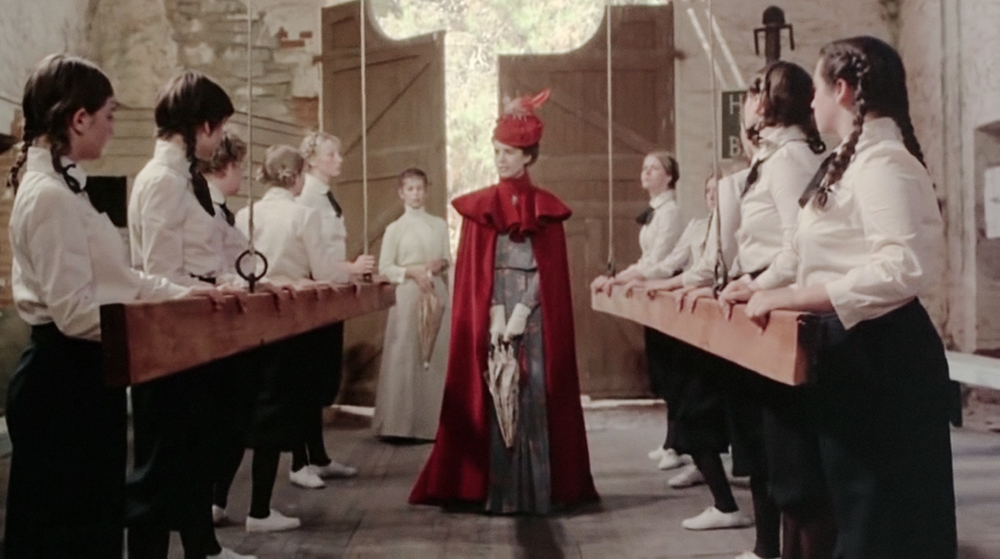

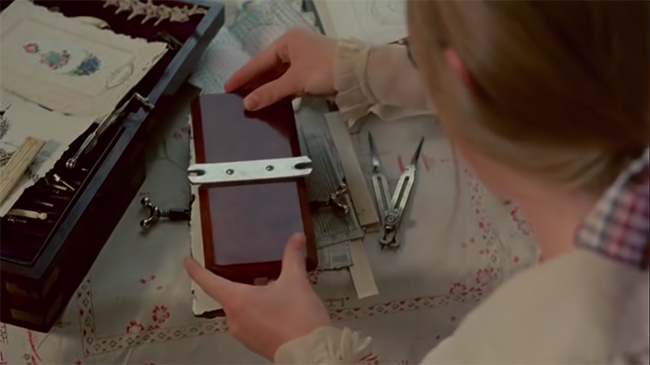

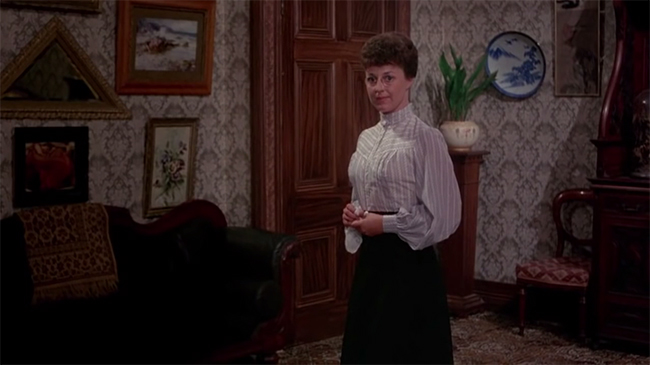

"The Wreck of the Hesperus" and "Casabianca" appear again in Lindsay's book (and Weir's film) in the gymnasium scene when the girls attack Irma. Having been found alive, and recovered, she returns to the school to visit her classmates, but instead of their being happy to see her they turn violent. For whatever reason--perhaps only because she wears red during her visit--I've found that many people look upon Irma as being vain, haughty, even malevolent, when in the book (and in the movie as well) she is anything but. She had been devoted to Miranda, was gentle, a confused victim of fate but also a survivor. Repeatedly, she is given as overcome with feelings of love for all, and later will become a philanthropist. When she returns to the school to say her goodbyes, Mrs. Appleyard, furious with being deprived of such a highly profitable, wealthy student, harshly reprimands her for leaving the college, telling her she's unprepared, that she doesn't know how to spell. Strengthened by her experience in that the world is quite larger to her now than the small college, amazed especially by the pettiness of the reproof over her spelling, Irma declares the only good things she learned from the school were through Miranda, which would be the importance of love and compassion. When Irma goes down to the gymnasium, the girls are doing their exercises to a battle hymn, "The March of the Men of Harlech". Irma representing the unknown, which they can't abide, and the loss of Miranda as well as the destruction of their previously stable lives at the school, the girls storm her. After Mademoiselle rescues Irma and calms the situation, she finds Sara bound by leather straps to a long board, a sadistic punishment disguised as a treatment intended to cure her stooping. She had been forgotten in the storm, forgotten in the dim of the building, and as the building had emptied she had been about to be forgotten completely, left there in her prison. She is the girl bound to the mast in "The Wreck of the Hesperus", while her schoolmates, exercising to a battle hymn, remind more of the boy in "Casabianca" whose trained loyalty and subservience binds to the battle ship. Irma had recalled him on the rock and understood he was doomed, but Edith had no comprehension of this. Edith was an example of one who may have learned poems by rote memorization but harbored no understanding of them, which was actually a problem of that style of instruction.

The hysterical attack on Irma also takes on disturbing connotations when we consider that Irma is likely Jewish. Her last name is Leopold and her mother was a Rothschild. It's not only that Irma represents the mysterious, unable to remember what happened, that draws their ire. After all, though Edith did not disappear, she too ascended the mountain and emerged from her ordeal with no memory of what had frightened her, and was unable to recount her story with any sensibility. Still, Edith had been brought back into the fold and perhaps even better accepted than before. But Irma? What was her crime? That she couldn't remember? A girl so traumatized that she spent weeks recuperating? It was Miranda they had wanted to return, but it was Irma who had risen from the dead, a news they first welcomed, but is a joy that collapses by the time she enters their midst to say goodbye. One could even look upon Irma as becoming a Judas figure, a betrayer. But to whom? Those who disappeared, who were left behind on the rock? Or the girls at the school, who have paid for the disappearance not only by being deprived of Miranda, but are now living under much harsher rule than before, the book disclosing that they are now banned from even talking together when not in the presence of a governess.

Irma is reviled by the girls who are as ferocious as Bacchantes.

In the movie, in her red cloak and hat Irma does by all appearances become a mix of Red Riding Hood overtaken by wolves, and perhaps a symbol of a full-fledged, fully initiated, menstruating womanhood. During her recuperation, away from the sexual segregation of the girl's college, she even developed an intimate friendship with one of the boys who had found her, Michael. By virtue of this little experience, she has advanced beyond the girls, leaving them behind, as she is now doing physically, going to Europe. Irma could not, even if she wanted, return to the college. Her experience has made her no longer subject to its laws and sensibility.

Irma is not, however, the only one who has worn scarlet. In the book, when Edith is interviewed after the disappearance, she wears a red cashmere dressing gown. Again, one of the things that distinguishes Irma from Edith is that for her recovery she was taken to live at a cottage on the estate of Michael Fitzhubert's uncle. She was separated from them. She was removed from the miserable school. And the girls have no doubt heard rumors of a romance with Michael.

Edith, heavier than the other girls and rather stereotypically presented as clumsy and unattractive in both personality and appearance, is in fact one of Irma's most vociferous attackers. All accuse Irma of knowing and not telling what happened. Blanche accuses her of having always possessed adult secrets. Finally, Edith declares she will tell them what Irma won't. "They're dead...dead! Miranda and Marion and Miss McCraw. All dead as doornails in a nasty old cave full of bats on the Hanging Rock." Now, for all they are aware, this is the truth, so perhaps it is Edith's spite that causes the governess to slap her, telling her, "You are a liar and a fool." At which point a girl named Rosamund, in the book, begins praying to St. Valentine, for the intervention of love, so that the others will leave Irma alone and the girls will love one another. Genial Tom then enters, one of the workers, and the fight is over. Almost. The French governess, Dianne de Poitiers, sends the girls to get ready for dinner then threatens fellow teacher and governess, Dora Lumley, with bashing her with an Indian club unless she promises not to tell Mrs. Appleyard about the incident. "I am perfectly serious Miss Lumley. Though I don't intend to give you my reasons."

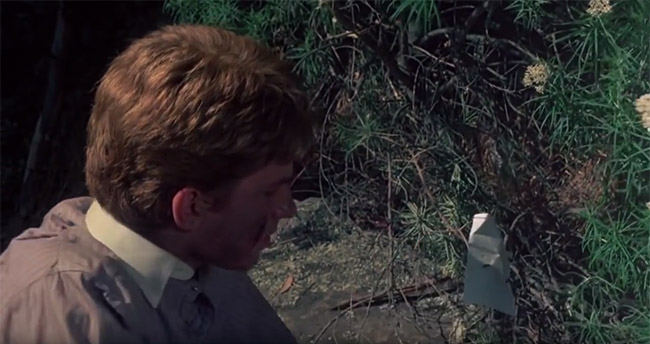

To me it's curious that Poitiers would call Edith a liar when she states that those disappeared are all dead in a cave, because this is the most logical end. Even in the 18th chapter we have the two girls and Miss McCraw disappearing into a hole in the ground and a boulder covering the hole over. But the 18th chapter provides also a metamorphosis so that McCraw, Miranda and Marion are not as they once were when this occurs, and are in a state of paranormal transition. The opportunity for a resurrection of sorts is denied the three with Edith's version, and we are nearing Easter, which is all about resurrection. The book making clear that all of the children have actually envisioned what Edith chooses to speak aloud, one of the girls remembers how the Bible speaks of the dead as crawling with worms and vomits, which sets them full into hysteria. Only one other reference to worms is in the book, also coincidental to Irma, and that is when Michael has been found delirious on the rock after searching for the missing. In the movie, Albert, after discovering Michael and bringing him help, is given by the mute Michael a bit of torn cloth from a woman's dress. After Michael is carried away, Albert desperately climbs up the rock and finds Irma. Instead, in the book, after Michael is found he is taken home and Irma is left to languish for another day. It is only realized Michael had come across something when, that night, Albert goes through the same notebook from which Albert was tearing pages for "flags" he left on bushes on the rock to mark his path. Opposite a page with the statement "worm powders", Albert finds the notation, "ALBERT ABOVE BUSH MY FLAGS HURRY RING OF HIGH UP HIGH HURRY FOUN". In the book, Albert then rouses help and returns to the rock to begin the search again.

The bible verse the vomiting girl recalls in the book would likely be one of two below.

And they shall go out and look on the dead bodies of the men who have rebelled against me. For their worm shall not die, their fire shall not be quenched, and they shall be an abhorrence to all flesh.

Isaiah 66:24

And whosoever shall offend one of these little ones that believe in me, it is better for him that a millstone were hanged about his neck, and he were cast into the sea. And if thy hand offend thee, cut it off: it is better for thee to enter into life maimed, than having two hands to go into hell, into the fire that never shall be quenched: where their worm dieth not, and the fire is not quenched.

Mark 9

As Tom, whose appearance stops the hysteria, has just had his teeth removed and is now toothless, arriving from the dentist, I'm inclined to think that Joan put some considerable thought into this and that toothless Tom's quelling the howling of the girls, following the vision of the worms, has to do with the word for worm in the Old Testament, coming from a word that means also "to blurt or utter inconsiderately". (For instance, Ginsberg's "Howl" made use of this.) The word is one used often with the ellipsis of 'shaniy', as a crimson grub worm, ShNI meaning crimson.

ShN means tooth and is associated with fire, ASh, which is why it is interesting that this episode begins with the worm, followed by descriptions of gaping mouths exposing the teeth and tongues of the girls, overwhelming poor Irma, and ends with the appearance of toothless Tom assuaging all, he described as an angelic messenger sent from heaven in response to Rosamund's prayer for love and kindness.

I may be completely off base in these associations in the above paragraph (and am prepared to be, I'm not bound to them) but present them because there is also the appearance of Manassa, a town, in the book. The "hell" of Mark's verse is Gehenna, which was considered especially cursed as it was said some of the kings of Judah sacrificed their children there by fire. Two names associated with the sacrifice are the kings Ahaz and Manasseh. I will return to this idea of Manasseh later, for "Manassa" is present in the book, and the idea of forgetting (Manasseh means to forget) is repeated often.

Wikipedia states in Jewish folklore the valley had a "gate" which led down to a molten lake of fire.

What is Hanging Rock but a violent outcropping of lava rock (to be equated with the fires of Gehenna), and how do the children access it on St. Valentine's day but by a gate. It was Miranda, an "experienced gate opener on the family property at home" who had climbed down from their carriage to open the gate to Hanging Rock, and as she did so a flock of parrots came out screeching overhead, startling the horses.

The 18th chapter version of the disappearance of the ecstatic girls and McCraw contrasts greatly with what seems to be represented here, the hell of a place associated with the sacrifice of children fitting in well with the necessity of the children committing to memory the poems of the boy who loyally burns to death on the ship and the girl lashed to a mast, both virtually sacrificed by their elders. The poetic choices that communicate British imperialism and the crushing of its own children in its traditions and obligations, the "Voice of Spring" of Hemans that so mourns the disappearance/death of children that spring abandons the living, become connected with the stories of the sacrifice of children during the reign of Manasseh, visions aroused of the place that was accursed due to those sacrifices, Gehenna. In the presence of Irma, as Easter approaches, a time of crucifixion, death, and hope for renewal, the girls are reminded of a celebration of love and freedom at Hanging Rock that turned into horror and continues to terrify, their companions ascended into the unknown, they vanished entirely, with no viable explanation from adults, and the girls sense now a spirit of sacrifice in the silent mysteries and the threat of worms, they betrayed by elders and gods, for Miranda and Marion must certainly be dead, and they too shall die as well some day.

There are many things that separate Irma from the rest of the girls. She is fabulously rich. She is one of the more beautiful. Before, she was one of their number. Now she is not. She was a child but has freshly moved into the secret world of adults. Easter quickly approaches and those who disappeared have not been returned. If Irma is Jewish then the girls may also be turning on her as representation of a failed Christ. In the poem, "The Wreck of the Hesperus", the girl tied to the mast prays to "Christ, who stilled the wave on the Lake of Galilee". But she is not saved. Irma was rescued but Miranda and Marion were not. Irma returned, but they are not rescued, still caught in the prison of the school they despise. With no answers from the adults as to what happened, they beg of Irma in their hysteria for her to tell them the truth, for not only did she survive, though she is newly crossed over into the adult realm she can possibly reveal to them the secrets of the adult world. But she can't help them in their despair. And this girl who was closest to the mysteries, to death and the eternal, is then one on whom they turn in serious and dangerous rage.

Which articulates one of the despairs of the Angle-European Christian, the Jew who is not a Jew. Though the Anglo-European Christian has received the promise of Christ, Christ has yet to return. And they will never be as close to god as the Jews for the Jews were first chosen, the first children of their god. They will never be as close to god as the Jews as they will always be the adopted ones, grafted into the tree of life. Working from a traditional church stance rather than a mystical one, they will never be at the "family" table.

It's telling that in both book and film Christianity is largely absent, however assumed to be the defacto religion, which it would be, and that Rosamund can only think to pray to St. Valentine, not an all-encompassing monotheistic god, not the sacrificed son of the monotheistic god who has either failed them or is dormant. Valentine seems less to be built on the church version and the Roman then a syncretization with Dionysus and the predominately feminine Bacchantes who in their revels are depicted as wild, unbridled. As Dionysus rules unbridled passions, then it is the Dionysus-Valentine who Rosamund believes has also the power to quell the passions and reunite with love.

In the next section, I compare the three who descend into the hole, the hanging rock then covering them over, with the three Marys who go to the tomb on Easter morning to find the rock of the tomb rolled away. Irma, as one who is in a sense rejected as she wasn't allowed into the hole, has as her principle injury some damage to her hands that shows she had been desperately scratching or digging at something. She might be separated out as the non-Christian, the Jew who didn't participate in the mystery of the open tomb, in as much as it was shut to her. If this is there, this is not Joan condemning her for indeed Joan ultimately provides a beautiful reason in the book for Irma being left behind and it is one of a couple of things that end in linking the character of Irma with Joan. Instead, I am examining why Joan would have chosen to have Irma be perhaps Jewish, and the reason for the hysteria against her. One thing that comes to mind is the holocaust. Joan's sister, Mim, had married a philologist named Hans Pollak and in 1938 Joan visited her in Austria, which was the year he was "suddenly retired by the Nazis in consideration of my Jewish blood". In 1939 they migrated to Australia to take refuge there, but first made their way, penniless, to London. Hans had siblings and nieces and nephews. I'm unaware if any died in the holocaust.

Hans Pollak's uncle on his mother's side was Leopold Pessl. His sister, Margarethe Grete married Dr. Rudolf Bum who had a sister named Leopoldine Lowenthal. Margarethe and Rudolf seemingly also fled to London in 1938. I'm not suggesting that the name Leopold might have been borrowed by Joan from this family, for Irma, but it was in the family and this seemed notable.

I had the feeling there might have been an intimate reason that Joan crafted Irma to be someone who was possibly Jewish, so wasn't surprised to find she had a Jewish brother-in-law.

Here we have the horrifying side of Hanging Rock as its shadows stretch long and threatening over Appleyard College. Now, for another version, which is instead a perspective of universal harmony.

It's clear from not only the 18th chapter, but the attitude of the girls as they ascend Hanging Rock, divesting themselves of shoes and stockings as they go, that Joan has made, in her story, an attempt to bring the disappeared ones into her comprehension of Australian Aboriginal dream time (or a version of it), but as a means of doing so she also utilizes classical mythology, in which metamorphosis played strongly. Ancient Christians and Jews weren't turned into deer, cows and swans in their myths, but Greek and Roman mythology has many such examples. Joan also relies on a combination of philosophy and esoteric mysticism for a kind of scientific validation, for if the vanguard of science is always "magic" to the uninitiated, whereas Miranda is the voice of love, Greta McCraw and Marion represent ancient philosophy or logic opening itself to the possibles availed by the dream time of the rock. Or that is my best way of putting it at the moment.

The indigenous landscape is dangerous to the non-indigenous through its conquering of the foreigners by conforming them to the landscape's spirit or destroying them.

Initially, it seems peculiar that McCraw and Marion would be seduced by the magic of Hanging Rock, that their mathematical minds don't react in horror, as with Edith who is distinguished as being irrational, their very opposite. Instead, a devotion to curiosity drives them. Plus, math, numbers, figures, are a universal language and so Joan represents them as being able to enter a dialogue with the rock and dream time. But their transformation isn't without its difficulties, especially so for McCraw who becomes close to a medium for the rock, such is the extent to which she leaves behind the trappings of her self which must be inessential to her core. In the 18th chapter, by the time we see her she is already much changed and struggling her way uphill to the girls, gasping, "Through", as if fighting with all her strength into this new atmosphere as she leaves behind the old. Even she says, realizing how she has stripped down, that the pressure on her physical body must have been "very severe". The extreme effort required of her, to reach her pupils, is to be compared with Michael's in his struggle to find Miranda (instead discovering Irma), his only conscious thought as he crawled over the boulders being, "Go on!". He has a dream on the rock, and in his dream his legs become useless as he swims through a viscous green water that threatens to choke him. He realizes when he comes to that it is his own blood he has tasted from a new and inexplicable head wound, but he almost has no comprehension of the wound as he has had simultaneously an all-consuming realization that drives him on, he "knows" someone is there, and believing it is Miranda he forces himself to continue climbing, assured of a breakthrough. Immediately injuring one of his legs, it becomes as useless as in the dream, just as Greta McCraw has no use of her legs in the end which become a kind of tail as she vanishes into the ground in the 18th chapter. Even Mrs. Appleyard has a similar dream of easily cutting through the water like a fish with her late husband, using neither legs nor arms, at approximately the time of the happenings on Hanging Rock, but she is woken by the sound of a lawn mower and then checks with Sara to see if she has yet learned her poetry.

Christianity and Judaism have the snake that invites one to taste of the fruit of knowledge in the garden. Australian Aboriginal myth has its own snake, the rainbow serpent. The girls had been warned by Mrs. Appleyard to beware of the dangerous snakes on Hanging Rock, and of course a snake must enter the picture as a guide. In the 18th chapter, a snake reveals to Miss McCraw, Marion and Miranda the hole into which they will disappear. There is no question about it, they must follow the snake, which Appleyard had warned them about, and that it was dangerous. Associated with water, the rainbow serpent of Australian myth may have a relationship with Miranda as she is later described as a "rainbow" and is also the embodiment of Venus. We may also have a connection with Marion, whose name in Hebrew means "bitter waters". The significance of water in association with the rainbow serpent may account for the watery dreams of Michael and Mrs. Appleyard, and, at the end of the 18th chapter, Miss McCraw's transformation into a crab-like creature, the kind that "inhabits mud-caked billabongs", which is the form by which she enters the hole. Again, concerning the waters, it is interesting that the three who go down the hole are known best by their names that begin with M: Miranda (despite her importance in the book she is never provided a last name), Marion Quade (who has, in a way, a mathematical last name, "quade" meaining "four"), and Greta McCraw. When McCraw appears, in the 18th chapter, she is only known as McCraw. M in the Hebrew is Mem, the letter of water, of the divine wisdom. The three Mems of Miranda, Marion and McCraw remind of Mary, Mary of Clopas and Mary Madgalene, the three women at the biblical crucifixion, all women whose names are watery. Again, there are traditionally three Marys at the tomb to whom Christ is first revealed upon the resurrection. Just as the three Marys appeared at the tomb to find the stone covering it rolled away, so too do these three enter the hole beneath the hanging rock which then descends and covers again the hole that had been revealed them. If Joan had a taste for the tarot, mem is the letter of the 23rd path, the 12th card, that of the Hanged Man, the mystic or traitor. The Judas or the one who is in the quiet repose of the reception of a great awakening. If only by their names would Edith Horton and Irma Leopold have not been candidates for the three Mems, though Irma made a close swipe with her name, coming from Emma, a Germanic name meaning "world". It at least had a mem in it. The letters of the name Irma are also contained in both Miranda and Marion. In Irma, Miranda and Marion we find Mari.

When Greta McCraw turns into a crab, she still is McCraw, if Joan was thinking of "craw" as in a "crayfish", from the Frankish krebitja, similar to to the Old High German krebiz, crab. This may explain why Appleyard dreams she is a fish swimming with her husband, for Appleyard's relationship with Greta McCraw is revealed as being, if not romantic and sexual, psychologically and emotionally marital. And they may be indeed romantically involved.

Aboriginal Australians are absent in Joan's story, exempting the one tracker who is brought in but fails to be any help in finding Miss McCraw, Marion and Miranda. But rather than being non-entities, it is by their absence they loom large throughout the novel. Weir, in his film, communicates an enduring Aboriginal possession of the land through capturing gigantic "faces" sculpted in the rock, which were even spoken about in interviews on the film and taken seriously as an overwhelming presence. The standard European concept of a linear timeline upon which one only incessantly moves forward is foreign to the Aboriginal conception of time that is bound up with the ever-present Dreamtime in which the past is ever ongoing. I'll not go into detail on the different conceptions of time, but this was a subject that fascinated Joan, and she likely felt that subject calling to her. She spoke of how her mere presence stopped watches, she couldn't wear one, and she didn't care for keeping time, thus her autobiography Time Without Clocks. (Those who do stop watches perhaps are inclined toward certain mystical conceptions of time.) In the novel time is literally stopped in its tracks by Hanging Rock. First Hussey, their driver, realizes his watch has stopped at high noon. McCraw realizes the same and suggests it has something to do with magnetism. Miranda no longer wears her "pretty little diamond watch" over her heart, while Irma states if she had Miranda's diamond watch she would wear it always, "even in the bath" and embarrasses Hussey by forwardly inquiring of him if he wouldn't do the same. Irma is not asked if she has a watch, and her remarks make it sound as though she doesn't have a diamond watch else she'd not envy Miranda her own, but later, after her rescue, when she is invited to lunch at Michael's uncle's home, she wears a tiny diamond watch. Mike warns her she must be punctual, but he purposefully misses the luncheon and excuses himself with a note stating that he had forgotten to consult his watch.

Luncheon at Lake View was at one o'clock sharp. Irma, warned by the nephew that unpunctuality was a cardinal sin in a visitor, smoothed out her scarlet sash in the porch and glanced at her tiny diamond watch...

Irma had, the day before the dinner, told Michael that Miranda used to say everything began and ended at exactly the right time. However his fascination with Miranda, he was certainly falling in love with Irma, the two bound by their experience on the rock, but this reminder of "the right time" seems a spur for his rejection of her. One wonders if Joan, in her own imagination, had Michael watching from afar to see if Irma would arrive punctually or be delinquent. Had she been delinquent, would he have not abandoned the romance? As two who neglected their watches, who weren't trapped in the Anglo-European prison of obligation to time, would they have remained together?

In the 18th chapter, Miranda remarks that they will arrive in "the light" as they are now perpetually at high noon, a place of no shadows. This is perhaps Joan's version of an Australian Aboriginal rainbow snake receiving the three wholly back into the fluid dream time, for which Irma is not ready. Not that she hasn't felt an ecstacy like that of the others, for she has and was even compelled to dance, and not that she isn't prepared to enter the rock, for Irma is, like the children of the Pied Piper, one who will follow the trusted Miranda even into the ground though out of the four she is the only one to be overcome with fear. She must finally keep asking what it is that the others are experiencing that she isn't, which began when she didn't feel the same pull of the "monolith" that so profoundly attracted the others. As they enter the rock, she begs for them all to stop so they may return home, yet it is obvious that if she was permitted to enter the rock, to follow, she would. But she is not permitted, for after the others disappear into the hole in the ground, the hanging boulder above falls down and covers the hole, Irma adamantly denied access.

We know none of this through the movie. The book, as it was published, doesn't let us in on the knowledge of a snake leading Miranda, McCraw and Marion to the hole down which they will disappear. But we do know enough to make a guess that their disappearance is mystical, because of their dream-like attitude, because of the stopped watches, and because of Pythagorean's Theorem.

Miss McCraw, on the way to Hanging Rock, notes that theoretically there should be no reason for them to return late back to the college. She points out that their journey thus far had been composed of two sides of a triangle, they having made a sharp right angle turn outside Woodend (where the girls were finally permitted to remove their gloves, only as they drew away from civilization), which meant the sums of those sides would be greater than the hypotenuse. She posits that instead of returning the way by which they came, they should travel home by way of the third side of the triangle in order to get there the more quickly.

Rather than have this conversation in the film, Weir instead supplies a visual of a triangle while they are picnicking (and also while they are traveling to the rock, for they pass a triangular watering hole at the beginning). After Marion, Miranda, Irma and Edith have left to climb the rock, when all the girls who remained at its base eventually take their afternoon naps, McCraw, with an air of either curiosity or uneae, looks from a page of her math book to the rock. We have the visual of her eyes moving to the rock via a mathematical theorem concerning a triangle and circle. It is a problem on page 221 of Sidney Luxton Loney's 1893, Plane Trigonometry, An Elementary Course, Excluding the Use of Imaginary Quantities.

Below are some of Weir's other triangles.

Near the beginning, he pairs Marion, cleaning the circlets of her glasses, with an equilateral triangle enclosing a shell shape in her window.

Mrs. Appleyard, in her study, is observed with a red equilateral triangle behind her that serves as a frame for a picture. We are never given a good close-up of it, but there appears to be a woman on the left and perhaps a child on the right. The triangle also can be thought of as framing a circle. This frame remains on her mantle throughout the film.

Weir has the flaps for the very vehicle in which the girls will travel to Hanging Rock manifest a triangle. It travels a circular path.

The triangular waterhole at the beginning of their journey to Hanging Rock rests apart from but alongside a sharp bend in the road.

There are other triangles as well, such as the pediments above the windows at Appleyard College. Do we include those? And there is a most notable triangle that I've not included in this section but will get to later.

Joan describes Miss McCraw as being angular, shaped like a flat iron, and when she is fully divested of all but her underwear in the end she is revealed as being triangular in shape. She is essentially math. On the other hand, when Irma leaps over the stream on her walk up to Hanging Rock with the others, Albert remarks that she has an "hourglass" shape, which again aligns her with time. That this comment was in the film but not in the book suggests Weir perhaps understanding that Irma's lack of antipathy for keeping time separated her from the others who disappeared.

A Mason of Queensland, Australia writes on the sacred geometry of Pythagorean's Theorem, which is important to freemasonry:

According to Plutarch (46 - 120 C.E.), the Egyptians attributed the sides of the triangle in this fashion. The vertical line was of 3 units and attributed to Osiris. The horizontal line was of 4 units and attributed to Isis. And the hypotenuse was, of course, 5 units and attributed to Horus, the son of Osiris and Isis. It is noteworthy that Plutarch studied in the Academy at Athens and was a priest at Apollo's temple at Delphi for 20 years. In the myth of Osiris and Isis, Osiris is killed which makes Horus the Son of a Widow and links him with Hiram!!

The units of the triangle's side are significant. The three units of the Osiris vertical have been attributed to the three Alchemical principles of Salt, Sulphur and Mercury. All things are manifestations of these three principles according to Alchemical doctrine. The four units of the horizontal line of Isis relate to the so-called four elements: earth, air, water, and fire. These are of course the four Ancients. The ascending Horus line with its five units represents the five kingdoms: mineral, plant, animal, human, and the Fifth Kingdom. This is the Path of Return. The ascending line finally connects back up with the Osirian line. The Fifth Kingdom symbolizes the Adept as one who has consciously reunited with the Source of all Being.

Source: http://www.freemasons-freemasonry.com/geometry_masonry.html

This is the Path of Return. And such is the path of return that Miss McCraw had suggested they take, mystifying the others, then followed up with some quip about how the mountain had come to Mohammed and now the mountain had come to Mr. Hussey, the driver of their wagon.

When Mr. Hussey realizes his watch has stopped, the French governess is unable to check her own as it is being repaired at a shop in (drumroll) Golden Square. Again, Pythagoras, math, the golden ratio. Later, when she realizes Miranda is a Botticelli angel, she announces, "Now I know!" Greta asks her, "What do you know?" Rather than answering, Dianne privately muses it would be "impossible to explain or even think clearly on a summer afternoon of things that really mattered. Love for instance, when only a few minutes ago the thought of Louis' hand expertly turning the key of the little Sivres clock had made her feel almost ready to faint..."

Greta would have understood if Mademoiselle's entrancement had been described in terms of math. In fact, Tom, the handyman, crafted a joke valentine for her of squared paper covered with sums. "She had received it with dry approval, figures in the eyes of Greta McCraw being a good deal more acceptable than roses and forget-me-nots. The very sight of a sheet of paper dotted over with numerals gave her a secret joy...they could be sorted out, divided, multiplied, re-arranged to miraculous new conclusions." One has the sense that Dianne de Poitiers' heart is being fixed by the repairman whom she will marry on Easter, their romance spurred by the drama of the disappearance of the girls, it likely their engagement would have been a protracted one if not for their disappearance. So, too, the housemaid, Minnie, and her lover, Tom. It's after the disappearances that they as well become engaged to be married on Easter (Minnie soon realizes she is pregnant) and leave the service of Appleyard College. The short route home for these two couples begins that day, a physical one bound to romantic, worldly love. Whereas Greta, Marion and Miranda enter into the eternal light of noon, their loves being abstract.

If at first it is difficult to comprehend why McCraw and Marion are the ones found by this dream time and so fully acquiesce, with only a little consideration it should become even more difficult to understand how Miranda might be so easily swept away. She is loving and beautiful almost to a fault in that she is conspicuously so in both book and film, but especially in the book. She is compassionate, engaged and involved with others. And yet she appears to willingly abandon herself to a mystery that has catastrophic ripples, at least in human eyes--the ensuing miseries of the families of Miranda and Marion, the death of poor Sara, as well as the deaths of unsavory characters such as Mrs. Appleyard, Miss Lumley, and her brother. With or without the 18th chapter, the impression is had of Miss McCraw, Marion and Miranda permitting themselves to cross or be carried across a boundary of no return, Marion and McCraw the two most intellectual of the characters, while Miranda represents love, the heart as one's spiritual guide. Miranda does warn Sara, beforehand, that she (Miranda) will be gone soon and so Sara must learn to love others. This assumes premonitory dimensions in the film even before the disappearances occur, while in the book this bit of history isn't disclosed until much later, but Miranda is also a senior who would, indeed, soon be leaving school, and the younger Sara was going to have to learn to live without her. Though the movie sets up a possible sexual context for their affection, and the book allows that there are no possible (male) suitors for the girls until they go into the world, the book makes clear that Sara is the youngest student at Appleyard, being only thirteen, and her relationship to Miranda, though intense, is that of a young orphan who has placed all their trust in one individual. Had Sara heeded Miranda's warning, she would have survived the prospect of being returned to the orphanage when her guardian failed to pay her tuition on time. She was no sooner dead than her guardian wrote that he would be picking her up for Easter vacation, and had that not occurred the arts teacher had previously written Sara insisting that she take refuge in her own home. Though the arts teacher's letter didn't reach Sara in a timely fashion (delays drive much of her sorrow), it would have eventually. Joan seems to want to have shown that Sara had loving, caring recourses to which she closed herself by responding principally to Appleyard's hatred rather than to the love expressed by others.

But she too ends up arriving "in the light", as with Marion, Miranda and McCraw. When Sara dies she visits her brother in a vision or dream that makes his dark room bright as day. However, she has had to come a "long way". Perhaps she has had to come the long way because the "short route", her return home, had already been taken and she had to travel the longer sides of the triangle to reach Bertie.

Stepping back to the relationship of Sara and Irma, and the lesbianism that seems to be in the film, less so in the book, Weir says he was shocked when these relationships between the girls and Mrs. Appleyard and McCraw were interpreted as lesbianism, that this hadn't been on his mind. Perhaps this is so. But he also has Sara as being on level ground with Miranda age wise and Sara's pining appears to be something other than in the book.

All [the Valentines] were madly romantic and strictly anonymous--supposedly the silent tributes of lovesick admirers; although Mr. Whitehead the elderly English gardener and Tom the Irish groom were almost the only two males to be so much as smiled at during the term.

Either the Valentines were crafted by Santa or the girls were expressing affection and even crushes, the sexuality fluid, some purely platonic and others not. Joan makes room for speculation but the fact they're all anonymous may be her way of limiting things with no directly expressed avowals. But this isn't the case in the film. Miranda reads her valentine that is given her by Sara, while Sara sits eagerly and devotedly by, seeming pretty clearly lovesick. The other girls read valentines that also seem to have been given them by those who rest nearby silently listening. The school is steeped in sensual feeling. Whatever will happen when the girls are unleashed into a mixed sex world, as represented in the film and book they are all vestal "virgins" of love who are apart from the "masculine" world, protected from the masculine world with their being housed at a girl's college where they are somewhat ironically being educated for marriage, to fill a particular kind of Victorian role in marriage, and are expected to enter marriage with their "virtue" intact. Rather than expressing an interest in Michael or Albert, who are nearby at the picnic area, the girls retire among themselves. An exception is Irma, who with some gentle forwardness plays with exercising her sexuality on the elder (and quite safe) Hussey, embarrassing him when she states she would wear such a watch as Miranda's always, even in the bath, then asking if Hussey would, which is to invite Hussey to imagine her in the bath and placing herself in the position of imagining him in his bath, and so he becomes uncomfortable.

Irma was unable to follow Miranda into the ground because of Michael. In the book it's eventually divulged that as soon as she saw him on the plain, she realized he was the love of her life. She is thus too attached to the world. And Michael reminds, though his fate is different, of Sara, whom Miranda had said should learn to love others. He too becomes fixated on Miranda. Seeking Miranda on the rock, he instead discovers Irma, which is almost a disappointment for him. Miranda is "love" personified but is also abstract in that she is a spirit. "Love", in the form of Miranda, was indeed leading Michael to Irma, but though he and Irma are attracted to one another he is unable to transfer that "love" to her and drops her in his rude way on a day that seems to answer his rejection with a furious, angry storm. They will never meet again.

When reading Picnic at Hanging Rock, considering the time I've spent analyzing Kubrick, it struck me how similar in tone was Joan's language respecting "Hanging Rock", the power of the transformative "monolith" on it, to Kubrick's monoliths, specifically the one in 2001: A Space Odyssey. There were also similarities in their treatment of time, especially in Weir's interpretation of Joan's circularities, and his attempt to express them in the film. These were similar to Kubrick's deja vu's and what I've written concerning his use of anamnesis. Kubrick's films are infused with such.

This would be due Nietzsche, for Joan's conception of Hanging Rock's monolith must have been greatly inspired by Nietzsche, she perhaps finding in his conception of circular time something similar to her own and even perhaps her understanding of Australian Aboriginal concepts of time which are cyclical. Which is not to say that she might not have developed/felt these concepts for herself apart from Nietzsche. She likely had spontaneous realizations. But due the significance of the "monolith" I assume a connection to Nietzsche.

The moment we read in the 18th chapter that, at the monolith, the girls enter a state of perpetual noon, we know Nietzsche's influence, his experience at a natural "monolith" in the mountains giving rise to his philosophy on time.

And in every one of these cycles of human life there will be one hour where, for the first time one man, and then many, will perceive the mighty thought of the eternal recurrence of all things:- and for mankind this is always the hour of Noon.

The reason I say Joan's "understanding" of Aboriginal time, qualifying this as regards her perception, is we don't know her exact beliefs and we have no assurance that they would have been in accordance with Aboriginal conceptions.

Before going on to Nietzsche and his monolith, I'm going to copy whole an entire page "plus" from The Natural Mysticism of Indigenous Australian Traditions by Joan Hendriks and Gerald Hall, a paper intended to show that "What we call a natural mysticism of embodied knowledge of place is very different to the mysticism of the romantic or theistic traditions--or even to the non-theistic traditions of the East...Indigenous Australians are not only inheritors of a spiritual tradition that reaches back to the very beginnings of human life and culture, but...the insights of that tradition are crucial for reconnecting us to nature, the earth, the cosmos and, ultimately, to God. This is not the experience of God in, above or of nature; but the experience of a Presence in which humans know in a bodily and profound way their connection to the cosmic rhythms...and the divine mystery..."

The Australian Aboriginal way of being-in-the-world is not--or, at least, prior to the experience of Western colonization, was not--centred on temporality, but spatiality. According to Tony Swain, the failure of Europeans to appreciate--and enter into effective dialogue with--Aboriginal Australians has much to do with this disparity of world-horizons which centre on space (Aboriginal) and time (European). Aboriginal attachment to a particular place, land, country or sacred site belongs to another order of experience, a different type of consciousness--indeed what we can reasonably call a mystical experience of place. This requires some explanation.

The notion of Alcheringa or Dreaming, admittedly often (mis)translated Dreamtime, expresses a specific ontology that inextricably links all life to land, place and country. With reference to the Pintupi people [an Aboriginal people of the Western Desert region of Australia], "individuals come from the country, and this relationship provides a primary basis for owning a sacred site and for living in the area". Tony Swain elucidates this relationship between individual and land with reference to Ancestral beings and human conception.

As Ancestral beings gave extension to place they imbued it with their own being, and it is this stuff of existence, this life potential of land, which is lodged within a woman who thence is pregnant. The mother does not contribute to the ontological substance of the child, but rather 'carries' a life whose essence belongs, and belongs alone, to a site. The child's core identity is determined by his or her place of derivation. ... Life is annexation of place.

Consequently, a child's identity is derived from a particular place marked by a spiritual and totemic ancestry. So important is this tie of Aboriginal people to a specific place that they perceive the land around them as everywhere filled with marks of individual and ancestral origins as it is dense with story and myth. For Aboriginals to be removed from that country to which they belong is for them to be deprived of their very soul. It is their spiritual and physical homeland. It is no wonder then that the institutionalized practice of forced separation of children from their families, country and places of origin--the so-called 'Stolen Generation'--resulted in such profound psychic and spiritual displacement.

When we say that spatiality--the sacred sense of place--is the distinguishing feature of Aboriginal ontology, we are not suggesting a world devoid of past, present and future. However, such a world does not privilege temporality or history in the way of most other cultures. The abiding place of the Ancestors in Aboriginal cosmology, for example, is not understood in terms of a lineal genealogy. Time does not link the Ancestors to the present; it is through place or country that the rhythmic events of life are co-joined through the Dreaming to the time before time. In the words of one commentator:

The shallowness of genealogical memory is not a form of cultural amnesia but rather a way of focusing on the basis of all relationships--that is, the Jukurrpa and the land. By not naming deceased relatives, people are able to stress a relationship directly to the land. It is not necessary to trace back through many generations to a founding ancestor to make a claim.

According to Swain, there are two types of events which circumscribe Aboriginal life which he terms Abiding events and rhythmic events. Abiding events are in one sense linked to the past--and in that sense to the 'time' of the Dreaming; but the Dreaming is also now. If we are to use temporal metaphors to speak of Abiding Events mediated through the Dreaming, we are immediately led to an atemporal realm elsewhere described as "Everywhen", "Eternal Now" or "Ancestral Present". All this is to suggest that Abiding events are beyond change; history and time are irrelevant.

Aboriginals also construct their world according to rhythmic events. Again, one is mistaken to suggest that Aboriginals live according to 'cyclical time'--sometimes stated to make a distinction with 'linear time'. Rather, says Swain, they live a "sophisticated pattern of events in accordance with their rhythms". The manner in which rhythmic life events are co-joined to Ancestral Abiding events is not through memory, genealogy, history or time (linear or cyclical), but through place.

Now to return to Nietzsche, and here I shall quote myself, from my analysis on 2001.

We can't overlook the significance of the use of Richard Strauss' Also Spake Zarathustra, which was inspired by Nietzsche's Thus Spake Zarathustra, the "Sunrise" section here playing. A central idea was the eternal recurrence, had by Nietzsche during a walk when he saw a pyramidal block of stone in the alps. Another is that of humans as a transitional phase between apes and superhumans--the notion of the superhuman, of course, becoming an influence on Nazism, though Nietzche (d. 1890) was himself said not to be anti-Semitic, and was a critic of German nationalism.

The cyclical, recurring nature of life that Nietzche proposed appears to have been one locked into a perpetual reconstitution of things such as there is no deviation.

What, if some day or night a demon were to steal after you into your loneliest loneliness and say to you: 'This life as you now live it and have lived it, you will have to live once more and innumerable times more' ... Would you not throw yourself down and gnash your teeth and curse the demon who spoke thus? Or have you once experienced a tremendous moment when you would have answered him: 'You are a god and never have I heard anything more divine.'

Also...

"Whoever thou mayest be, beloved stranger, whom I meet here for the first time, avail thyself of this happy hour and of the stillness around us, and above us, and let me tell thee something of the thought which has suddenly risen before me like a star which would fain shed down its rays upon thee and every one, as befits the nature of light. - Fellow man! Your whole life, like a sandglass, will always be reversed and will ever run out again, - a long minute of time will elapse until all those conditions out of which you were evolved return in the wheel of the cosmic process. And then you will find every pain and every pleasure, every friend and every enemy, every hope and every error, every blade of grass and every ray of sunshine once more, and the whole fabric of things which make up your life. This ring in which you are but a grain will glitter afresh forever. And in every one of these cycles of human life there will be one hour where, for the first time one man, and then many, will perceive the mighty thought of the eternal recurrence of all things:- and for mankind this is always the hour of Noon".

I'm less concerned with Nietzche's conception of what all this exactly meant for him than Kubrick's intentions in use and repurposing, for Kubrick's works are all about the conflict of predeterminism (the oracle) and free will, and repetition as found in ideas concerning anemnesis and ZKR (which I've written at length on elsewhere, consult the links). His recurrent usage of deja vu and characters revisiting situations is all an expression of this, the traversing of the duplicate or similar patterns of a maze or labyrinth in the journey to the center. So, though Nietzche writes of a locked-in life, and we need to have an understanding of Kubrick's references, Kubrick's use of these ideas must be considered in context of his expression of certain themes throughout his oeuvre and how he played them out.

Nietzsche's emotional experience of his own monolith which he encountered (a pyramid in the mountains) was that it was "6000 feet beyond man and time". Joan's "monolith" is also beyond man and time, the book and film making clear how confounding it is to most of the schoolgirls that Hanging Rock, as described by McCraw, was not thousands of years old but one million years old and formed of lava that was many millions of years old. The idea of this millions and millions was so perplexing to Edith as to horrify her. She couldn't begin to conceive of millions and millions though Irma tried to give context with her father having made millions from his mine in Brazil, and Marion pointed out that Edith herself was made of millions of cells. Joan's Hanging Rock is also clearly intended to embody Aboriginal ancestors/spirits tied to this particular place, and there is had a transformative collision of the present and the past's perpetual enduring.

It would be difficult to discuss particulars of Joan's ideology in respect of Nietzsche and Aboriginal concepts. Instead, it is enough to know that Joan must have felt correspondences with both, and that she perhaps interpreted both according to her own impositions/perspectives, as do we all tend to do.

I've done my own comparison of movie dialogue with the book, but then I was looking at an online version of the script and found something I'd not heard. Following the dialogue between Michael and Albert in which Albert talks about how at the picnic grounds the Fitzhuberts "never go for a walk or nothing", an online script says that as the buggy (drag) pulls up to the rock's gate, Hussey says to the girls, "Take your hats. Let's go walk about now."

I'd not heard this, but it makes complete sense--and not as if we might not have already picked up on hints at a version of the Australian Aboriginal walkabout.

Wilderutopia helpfully has the following:

Walkabout refers to a rite of passage during which male Australian Aborigines would undergo a journey during adolescence and live in the wilderness for a period as long as six months.

In this practice they would trace the paths, or "songlines," that their ancestors took, and imitate, in a fashion, their heroic deeds. Also called a dreaming track or footprints of the ancestors, one of the paths across the land (or sometimes the sky) which mark the route followed by localized "creator-beings" during the Dreaming. In the Aboriginal world view, every event leaves a record in the land. Everything in the natural world is a result of the actions of the archetypal beings, whose actions created the world. The paths of the songlines are recorded in traditional songs, stories, dance, and painting.

The Australian Aborigines speak of jiva or guruwari, a seed power deposited in the earth. In the Aboriginal world view, every meaningful activity, event, or life process that occurs at a particular place leaves behind a vibrational residue in the earth, as plants leave an image of themselves as seeds. The shape of the land -- its mountains, rocks, riverbeds, and water holes -- and its unseen vibrations echo the events that brought that place into creation. Everything in the natural world is a symbolic footprint of the metaphysical beings whose actions created our world. As with a seed, the potency of an earthly location is wedded to the memory of its origin.

A knowledgeable person is able to navigate across the land by repeating the words of the song, which describe the location of landmarks, waterholes, and other natural phenomena. In some cases, the paths of the creator-beings are said to be evident from their marks, or petrosomatoglyphs, on the land, such as large depressions in the land which are said to be their footprints.

"Aboriginal Creation myths tell of the legendary totemic being who wandered over the continent in the Dreamtime, singing out the name of everything that crossed their path -- birds, animals, plants, rocks, waterholes -- and so singing the world into existence." -- Bruce Chatwin in "Songlines"

In the book, at the end Michael goes on his own walkabout. It's not phrased as such but this is what it means when he leaves to familiarize himself with North Queensland. He invites Albert to go along with him and at first it seems Albert will not have the means to do so, but then he receives a good bit of money from Irma's parents, thanks for his role in saving Irma, and he is able to go.

Joan weaves into her story hints of Walkabout and Aboriginal myth along with Roman-Greco mythology and biblical mythology, Victorian sensibilities, and such things (it would seem) as Nietzsche's eternal recurrence, so keep this in mind as one negotiates the terrain. It is not all one or the other. We have a complex multi-layered combination.

For instance, Joan brings in Anglo-Euro ancestral heritage, making a comparison, when she has Michael musing, "He reminded himself he was in Australia now: Australia, where anything might happen. In England everything had been done before: quite often by one's own ancestors, over and over again. He sat down on a fallen log, heard Albert calling him through the trees, and knew that this was the country where he, Michael Fitzhubert, was going to live." Michael knows of the walkings in those ancestral echoes in England, but we can't stop there, for later Michael does experience those echoes at the rock, in the "Go on!" passage.

There was only one conscious thought in his head: Go on. A Fitzhubert ancestor hacking his way through bloody barricades of Agincourt had felt much the same way; and had, in fact, incorporated those very words. In Latin, in the family crest: Go on. Mike, some five centuries later, went on climbing.

In the book, Hussey asks Edith why she is called Edith (she had inquired why he called his horse Duchess) and she responds it was her grandmother's name, then adds, "Only horses don't have grandmothers like we do." Hussey replies, "Oh don't they just!", Joan has all life affected by the ancestors.

Joan certainly makes use of Australian "place" with the heavy sense of ancient Aboriginal presence at the rock, but she is also looking for parallels that transcend place.

Weir certainly has sympathy for Aboriginal spirituality, going on to make The Last Wave after Picnic at Hanging Rock. In the manner in which Weir subtly communicated in Picnic at Hanging Rock the eternal round and a sense of deja vu, I'm not, however, certain that he was sharing his interpretation of Joan's conceptions (which are never articulated in depth) or his interpretation of Nietzsche's or his interpretation of what he understood of Aboriginal time. As I said previously, it would be difficult to sort out and discuss the particulars of Joan's concepts, just as here it would be difficult to discuss exactly whose lead Weir was following, but it can easily be shown that he was attempting to visually communicate the eternal round through a disruption of strict chronology.

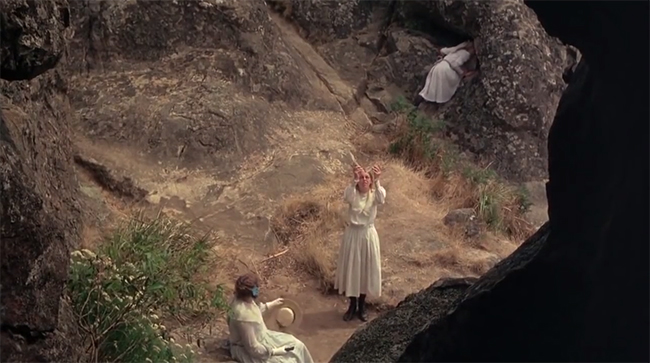

So let's look at his depiction of the ascents up the rock.