PORTRAIT OF LOLITA, AN ANALYSIS OF THE FILM'S USE OF THE GEORGE ROMNEY PAINTING

Go to TOC for this film ( (which has also a statement on purpose and manner of analysis and a disclaimer as to caveat emptor and my knowing anything authoritatively, which I do not, but I do try to not know earnestly, with some discretion, and considerable thought).

I've pulled several sections from my Lolita analysis in which I examine the significance of the portrait of the woman through which Humbert Humbert guns down Quilty. This first section involves the Lolita "Love Theme" which we first hear over the credits as Humbert Humbert paints Lolita's nails. The portrait will not appear yet to be involved, but we will see how it is by the time we get to the third section.

The first section is: The Films The Seventh Veil and Too Young to Kiss, Rachmaninoff and Nelson Riddle's Lolita Love Theme

The second section is: The George Romney Portrait, The Picture of Dorian Gray, "The Vane Sisters", and Shakespeare

The third section is The Painting of the Toenails, Scarlet Street, The Woman in the Window, La Chienne, Modigliani's Elvira, Vivian Darkbloom, and the Confusion Between the Muse and the Artist

I was presented with a possible Lolita puzzle piece--one of those puzzle pieces you don't realize is a puzzle piece until you stumble onto it--when Too Young to Kiss was playing on TCM. The story concerns a 22-year-old pianist who, having been unable to meet with a promoter, learning that he will be at an event for young talent, passes herself off as a 12-year-old and finally gets a hearing. He (Van Johnson) is wowed by the 30-something June Allyson in pigtails and brightly polished Mary Janes and promises her an amazing career. When June presents herself as the 12-year-old's older sister, hoping to transfer Johnson's enthusiasm to her own skills, Johnson takes a disliking to her, an antipathy that intensifies when he later sees the 12-year-old "Molly" smoking and drinking alcohol. Molly's older sister is a bad influence! So Van whisks Molly off to his estate in the countryside where he will reform her, give her a good spanking, and prepare her for her career as a concert pianist. Van also ends in reforming himself as well through the introduction of Molly to the pleasures of bike riding and amusement parks. He enjoys himself. The stellar moment of the film occurs after Van declares his desire to adopt her, thinking of her as a daughter, then challenges her to a race to the dinner table. "Last one in is a rotten egg." It's pretty funny, actually. Then Molly goes and ruins the family vibes that night by planting a kiss on him. A perplexed Van flees. Van realizes he's been had just prior Molly's big concert, introduces her as a great talent anyway, then stands about watching her play from different angles in the concert hall. Of course she loves him, and he realizes as he watches her play Grieg's Concerto in A minor that he loves her, but is conflicted. The film ends with them getting together, of course.

While I was watching, I don't recollect at what point, I suddenly had, for a split second, a moment of Kubrickian Lolita deja vu. One might think this kind of film would be creepy Lolita vibes all over, but despite the danger zone it wasn't. Certainly, though this is a parody, we have still the trope of the mentor/guardian linking up romantically with the young protege, but June and Van handle it well. I've never cared much for either actor but I rather liked them in this, June doing a weirdly able job of pretending she was 12, aided by her height (very short) and the fact she has no sex appeal whatsoever in any film I've ever seen her in. Pigeon-toed and tied up in pinafores, smoking and drinking and bullying Van when he makes her give up her bad habits, she's kind of fun. Van's transition from seeing her as a child to viewing her as a woman occurs during the concert hall scene toward the end. I wondered why so many minutes were being expended on the scene, Van moving all over the hall to view her from different angles, then realized it was the film's way of providing space for Molly to transition to an adult in Van's eyes, providing time for the audience to move to viewing them as an adult couple as well. It was at some point either during that scene or after it that I had the moment of Kubrickian deja vu.

Was it the music? I wondered if I began to feel that deja vu ping when June was playing the Grieg concerto? No, the Grieg didn't remind me of Lolita but something else about the scene did. I looked up the Grieg Piano Concerto in A Minor anyway and found that back in 1945 James Mason (yes, Humbert Humbert of Lolita) was in a film called The Seventh Veil and the Grieg piano concerto was featured in that. What was the film about? Well, it was about another child-adult romance, in this case a wealthy, young misogynist becoming ward over his orphaned young "niece" who is instead something like his 2nd cousin, absurdly played by Ann Todd, and whipping her into shape to be a concert pianist. He's not like Van. He's a possessive, manipulative, mean, aloof guy who exhibits only two emotions: cold annoyance and, occasionally, violent rage. He does have a soft spot for cats. In a peculiar scene, upon Ann's arrival, the camera goes in for a close up of a cat Mason is fondling on his lap. "Would you like to stroke him?" he asks as the close-up moves to his face. Ann says no. He asks why not. Because, Ann says, she's afraid of cats. Mason tells her she better get used to them. That's the first and last we hear about Ann's fear of cats. Her big, crippling fear is of canes, as her fine pianist hands were caned by a teacher for a ridiculous infraction the day she was to try out for a scholarship. Due the caning, she couldn't play. Mason, by the way, has a limp and walks with a cane. As Ann becomes older, she tries to separate herself from Mason's influence. At the age of seventeen she falls in love with a musician who plays swing and hopes to marry him, whereupon Mason slaps her across the face and whisks her off to a new life on the Continent. After seven years they return to London to live when Ann is asked to play Albert Hall. She falls in love with a painter Mason has hired to do her portrait and tells Mason she's moving to Italy with him. in response, as Ann mutely plays "Moonlight Sonata", Mason pleads with her in a way that is sure to win her heart.

Franchesca, I haven't deserved this of you. I always treated you as though you're my own daughter. All the love and sympathy I've had I gave to you. My life hasn't been a happy one. I haven't told you about it and I'm not going to tell you now. But you are the one beautiful thing that's been in my life. I can't live without you. You must know that. I can't give you up. I won't give you up! You're a great artist! Great artists just don't happen they have to be made and I've made you, I've spent 10 years training you, molding you, you'll be my life's work. And now I've got to throw it all away on a man who doesn't even want to marry you. Franchesca, listen to me! You can't stand up against me. You haven't got the strength. You'll do as I say. I demand that you give up this man. I demand that you send him away. Listen, we'll go to America. They've been asking for you in New York for months. And now we can go. We'll go. You and I together, Frenchesca. This happened before once, you remmember? You came away with me then. You weren't sorry, were you. You didn't really love that boy, and you don't love Layton. I'll tell you why. You belong to me. We must always be together. You know that, don't you? Promise me you'll stay with me always! Promise! Very well, if that's the way you want it. If you won't play for me you shan't play for anyone else ever again.

Now is when Mason strikes at her hands on the keyboard with his cane. She flees. A too convoluted plot eventually has Ann dipping into her past memories, via hypnosis, to find her way to what traumatizes her so that she doesn't wish to live any longer and believes she can no longer play the piano, by which process she discovers she loves her guardian, but it's by now quite all right as she's around twenty-four years of age. She eschews the painter and the swing musician and runs into the arms of Mason.

"Promise me you'll never leave me," young Lolita pleads with Humbert after she learns her mother has died and she fears being sent to juvenile hall.

The two scenes that strongly resonate between Too Young to Kiss and The Seventh Veil are the concert ones--Van watching June playing the Grieg in concert, and Mason watching his now adult 2nd cousin playing Rachmaninoff's Piano Concerto 2 in C Minor in the Albert Hall. As with Van, it's a transitional point for Mason in his relationship with his cousin, much camera time spent on her playing and his face as he watches her, we being informed that he is now obviously in love with her and aware of it.

At the end of the Rachmaninoff, James Mason looking on, the Kubrick deja vu struck, a dramatic, ascending chord progression being much the same as a central one in the Lolita Love Theme by Nelson Riddle. And when I looked up Rachmaninoff and Riddle I found that others were noting the heavy Rachmaninoff influence on the piece, but none mentioning this concerto specifically or its role in The Seventh Veil film.

That this particular piece by Rachmaninoff was used in The Seventh Veil film, in which hypnosis strongly figures, likely has to do with this concerto being dedicated to Rachmaninoff's hypnotist. Yes, he had a hypnotist. He went through such a profound writer's block that he tried hypnosis, found it successful and wrote this concerto.

As it turns out, Rachmaninoff and Nabakov had an association. It's given as minor but it was a huge one relative Nabakov's career. Rachmaninoff, hearing of Nabakov, feeling an affinity to him (they were both Russian etc.), gave him $2500 to move from France to America and start a new life. Interestingly, in Nabokov's Lolita, when Humbert gives Lolita the money to move to Alaska and begin a new life, he gives her $400 in cash in a check for $3600. In Nabakov's screenplay, he gives her $400 in cash and a check for $9600. However, in the movie, he gives her $400 cash and a check for $2500. A coincidental fluke, or an intentional reference, Kubrick having Humbert give Lolita a check for her fresh start elsewhere that is the same amount that Rachmaninoff gave Nabakov to have his fresh start in America?

The chord progression similarities in that one section shared between the Lolita love theme and Rachmaninoff's 2nd piano concerto--the shared dramatic, emotional crescendo--does lead me to believe that Nelson Riddle was referencing that concerto specifically, and thus was Kubrick referencing The Seventh Veil as well.

The idea of a seventh veil refers to Salome's Dance of the Seven Veils, first so-called in Oscar Wilde's Salome, by way of which Richard Strauss ("Thus Spake Zarathustra") also composed a "Dance of the Seven Veils".

I have written of how the portrait in Kubrick's "Lolita turns out to be prefigured by the same portrait in the movie The Trial of Oscar Wilde in which James Mason played, and is ultimately connected with "The Portrait of Dorian Gray" and Nabokov's "The Vane Sisters", and will extract that and use it here as the second section in my examination of the portrait.

There are a couple of veil references in Lolita. One is when they are at the drive-in watching "The Curse of Frankenstein", that scene opening with the monster ripping away the bandages to reveal his grotesque face, which is an allusion to Humbert Humbert. Later, when Humbert and Lolita are on their trip out west, after the first revelation of their being followed Lolita pulls a scarf over her face in the manner of a veil as "harem" music of a sort stereotypical for old cinema plays. Humbert is only annoyed with her as he is paying attention to the car behind them. We later realize she is trying to distract him, to turn his attention away from the car.

I should probably say a little something about Oscar Wilde's Salome. Once again, we have the story a man's infatuation with a girl young enough to be his daughter. In this case, Salome's mother's husband, Herod (half-uncle to Salome), has fallen in lust with her.

Salome is initially described as having hands like butterflies. Butterflies are a prominent motif in the Nabokov novel, and though not in the Kubrick film they do make an appearance in a framed case of dead and pinned butterflies at Camp Climax.

The Princess has hidden her face behind her fan! Her little white hands are fluttering like doves that fly to their dove-cots. They are like white butterflies. They are just like white butterflies.

Salome, before visiting the prophet, who she has heard says terrible things about her mother, likening her to Babylon, has become aware of her mother's husband's lust for her.

I will not stay. I cannot stay. Why does the Tetrarch look at me all the while with his mole's eyes under his shaking eyelids? It is strange that the husband of my mother looks at me like that. I know not what it means. In truth, yes, I know it.

Salome is at first horrified by the things John the Baptist said about her mother, but when she visits him she falls in love with this man who wholly rejects her rather than pursuing her as Herod does. She finds the prophet both beautiful and horrible in his ascetic denial of the physical. Her descriptions of her love and horror of him are a play on "The Song of Songs" attributed to Solomon.

Herod now overtly pursues Salome, even in front of her mother, going so far as to promise Salome her mother's throne. He demands her attention, and that she dance for him. She denies him, and her refusal both frustrates and inflames him further. She is herself now pale as the prophet in her love for this man who has denied her. Only when Herod promises to give Salome anything she wants does she concede to dance though her mother entreats her not to do so. Then, having danced, Salome asks for the head of the prophet, a demand her mother approves. Herod begs Salome to reconsider. She will not. As the king must keep his word, the prophet's head is delivered to Salome. She kisses its mouth.

Ah! I have kissed thy mouth, Jokanaan, I have kissed thy mouth. There was a bitter taste on thy lips. Was it the taste of blood?... But perchance it is the taste of love.... They say that love hath a bitter taste.... But what of that? what of that? I have kissed thy mouth, Jokanaan.

Herod immediately demands, "Kill that woman!" And Salome is slain by his soldiers.

Is it so horrible that Salome has asked for the head of the prophet, when he is imprisoned in the same cistern where her mother's first husband was kept for twelve years before being strangled? Even she says that it is as a tomb, the horrible black pit in which he's kept. The prophet has already, in essence, been put to death by individuals who are afraid to outright kill him as he is a man of god. Instead, they place him in a situation that might eventually cause his death. The assumption is that because of her having the prophet killed is the reason for which Herod puts Salome to death. Instead, if we consider Salome's last words, might it instead be her combined refusal of Herod and her description of love's kiss.

But Salome, having danced the dance of the seven veils, when she demands the prophet's head and kisses it, is already in the underworld, as Ishtar in search of Tammuz, or Inanna who wanted the knowledge of death and rebirth, each descending through the seven gates of the underworld and at each one relinquishing more of their possessions at each gate until finally there was nothing left and they became as corpses themselves.

Even a not very rigorous examination of Kubrick's films reveals that in each there is a descent to the underworld, and so too do Humbert and Lolita descend.

Return to top

In the first section I discussed Rachmaninoff and the opening scene of Humbert painting Lolita's toenails, subjects which have to do with Lolita's "portrait" and to which I will return to in the third section of this posting. In this section, I'm going to discuss the famous portrait itself that is gunned down before we even first meet Lolita.

It took me years to finally identify this famous portrait, so often given as being a Gainsborough yet had it been one we would have known long ago the mysterious subject. Eventually I looked for the portrait among Gainsborough's contemporaries and found the artist was George Romney. His subject was a Frances Puleston, her married name being Mrs. Bryan Cooke. Ten sittings were held for the portrait between 1787 and 1789 when Frances was about 22 to 24 years of age.

Frances was Col. Bryan Cooke's first wife. His 2nd marriage would be to Charlotte Bulstrode Cooke, not a relation, which may be of interest considering Humbert's 2nd marriage is to Charlotte Haze. Humbert's first marriage is briefly referred to in the film, but his first given "love" was Annabel Leigh, whom he felt he had found again in Lolita. In Nabokov's screenplay, he even has Humbert show Lolita a photo of Annabel and it was to have been of the same actress playing Lolita, Sue Lyon. I think we are all glad Kubrick did not pick up this idea of Nabokov's and run with it. Nabokov could get heavy-handed at times and wrote a lousy screenplay of his book.

Nabokov's Annabel Leigh was to serve as a pointer to Edgar Allen Poe's "Annabel Lee", a poem Poe perhaps wrote for his wife Virginia, they having married when she was just 13.

Another first/second wife comparison to make is that of Adam who was first married to Lilith before Eve, for Lolita's plight is a desperate one on the human level, but in mythological layerings she's connected with Lilith, Nabokov even mentioning this once. We should not confuse this Lilith connection with the child who was abused by Humbert Humbert. If she was as Lilith for Humbert, this has nothing to do with innocent Lolita.

George Romney, the artist, was also enamoured with a young woman, who is not the subject of this painting, but he did many paintings of this so-called "muse" in which she represented different mythological and legendary women, and so she became a very famous muse for her time. Her history was one of misuse by men in power. Made a mistress of Sir Henry Harry Featherstonhaugh when she was 15, they had a child together when she was 16, but he threw her over when she was about 17 and she subsequently became the mistress of Charles Francis Greville. Greville, too, would throw her over, by sending her to live with his uncle, Sir William Hamilton. Unbeknownst to this young woman, Greville had promised her as a mistress to his uncle, which she only learned about upon her arrival at his house. Despite this, she and Hamilton would marry, and later she would become even more famous for a love affair with Lord Horatio Nelson, carried on while she was still married to the elder Hamilton, the three even living together. This woman met George Romney when she was 17. He fell in love with her but the attraction wasn't mutual so she remained only his muse. Her birth name? Amy Lyon.

The two portraits below are of Amy Lyon, done probably several years before the one of Frances Cooke. In the first, she wears much the same style hat as in the Frances Cooke painting, only with black ostrich feathers rather than white.

Portrait of Amy Lyon (aka Emma Hart, Lady Emma Hamilton) by George Romney

Portrait of Amy Lyon (aka Emma Hart, Lady Emma Hamilton) by George Romney

Was Kubrick attracted to the portrait of Frances Cooke partly due its history? That it was painted by an artist who provided some name connections with Charlotte, and Sue Lyon who played Lolita? Not to mention that George Romney's name may allude to George in The Killing, the clown/fool who murdered his faithless wife even as he was dying, the gunshot wounds to the portrait in Lolita recalling the bullet holes in George's face.

Now is when things get really complex.

This portrait of Mrs. Bryan Cooke, by George Romney, has had few public showings, and if you do a search for it on the internet you will not find it referenced often. Its exhibition history, up to 1960, was Jan 6--March 14 in 1896 at the London Royal Academy of Arts, then June 16 to Sept 30 in 1943 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in NY. Were there duplicates or prints of it floating all about and so Kubrick was familiar with it? I don't know, but...

Not long ago (at least at the time of my first writing this, which was a few years ago now) I was watching the 1960 movie, The Trials of Oscar Wilde, in which James Mason plays the lawyer who defends Lord Queensbury against charges of slander made by Wilde (he had called Wilde a sodomite), the proceedings ultimately leading to Wilde's ruin. Lord Queensbury's son, Alfred Douglas, had met Wilde when he was 20 or 21 and they'd begun a turbulent relationship, thus Lord Queensbury's vitriol for Wilde. Lord Queensbury was out for blood and Wilde ought not to have pursued slander charges as things turned out quite badly for him when James Mason is able to produce teenage boys who could confirm that Wilde was a sodomite. Trials followed in which Wilde was accused of gross indecency and he ultimately went to prison for a time.

Previous to Wilde's slander charge against Queensbury, there's a scene in which Lord Queensbury and his family are brought together for the funeral of his eldest son, when the elder Queensbury has it out with Alfred Douglas over Wilde, and what did I spy in the background on the wall but the very same portrait of Mrs. Bryan Cooke by George Romney.

Portrait of Mrs. Bryan Cooke, by George Romney, making an appearance in "The Trials of Oscar Wilde"

James Mason, who plays Queensbury's lawyer, of course, was also Humbert in Lolita. In the first section of this post, I discussed some possible influence that the film The Seventh Veil, in which Mason also starred, may have had on Lolita.

By the way, speaking of veils, (in the first section I discussed Oscar Wilde's Salome and the Dance of the Seven Veils), Amy Lyon was famous for a dance she did with veils called Attitudes, in which she was nude and used veils and poses to conjure mythological and legendary women. This is referred to as a Dance of the Seven Veils in the movie That Hamilton Woman that sports Vivian Leigh as Emma. In it, Sir Hamilton, a collector of art and antiquities, examines a newly a cquired Greek bust that resembles one called "Clytie" (I'll come to that later), turns and examines opposite it a newly acquired painting of Emma (Amy Lyon), and then who appears in the flesh but Emma arriving at his mansion, yet unaware that she has been shipped down there to be a an art object mistress.

How did Kubrick become aware of this portrait, which Humbert blasts away at as Sellers/Quilty crawls behind it. Was it through film The Trials of Oscar Wilde? What the portrait was doing as backdrop fodder in the Wilde movie I don't know and is unimportant. Instead, what we now need to focus upon is Oscar Wilde and his book, The Picture of Dorian Gray, which concerns a libertine who remains youthful while his aging and all his cruelties are manifested in his portrait. Dorian only is able to die when he assaults and stabs the painting. Dorian becomes aware of his complicated relationship with the portrait after he causes the suicide of a young actress named Sybil Vane. He had fallen in love with her acting and promoted her to his friends as brilliant and the most beautiful creature in the world. The manner in which he describes her is significant, for it is the description not of a personality but a spirit that moves from person to person, age to age.

Harry, imagine a girl, hardly seventeen years of age, with a little, flowerlike face, a small Greek head with plaited coils of dark-brown hair, eyes that were violet wells of passion, lips that were like the petals of a rose. She was the loveliest thing I had ever seen in my life. You said to me once that pathos left you unmoved, but that beauty, mere beauty, could fill your eyes with tears. I tell you, Harry, I could hardly see this girl for the mist of tears that came across me. And her voice—I never heard such a voice. It was very low at first, with deep mellow notes that seemed to fall singly upon one's ear. Then it became a little louder, and sounded like a flute or a distant hautboy. In the garden-scene it had all the tremulous ecstasy that one hears just before dawn when nightingales are singing. There were moments, later on, when it had the wild passion of violins. You know how a voice can stir one. Your voice and the voice of Sibyl Vane are two things that I shall never forget. When I close my eyes, I hear them, and each of them says something different. I don't know which to follow. Why should I not love her? Harry, I do love her. She is everything to me in life. Night after night I go to see her play. One evening she is Rosalind, and the next evening she is Imogen. I have seen her die in the gloom of an Italian tomb, sucking the poison from her lover's lips. I have watched her wandering through the forest of Arden, disguised as a pretty boy in hose and doublet and dainty cap. She has been mad, and has come into the presence of a guilty king, and given him rue to wear and bitter herbs to taste of. She has been innocent, and the black hands of jealousy have crushed her reedlike throat. I have seen her in every age and in every costume.

After Dorian proposes to Sybil, he takes his friends to see her perform and is horrified by how her performance is now artless. Afterward, Sybil relates to Dorian how marvelous it is that she can no longer act, her love for him being the cause, as it has made life finally more real and important to her than the stage.

The painted scenes were my world. I knew nothing but shadows, and I thought them real. You came–oh, my beautiful love!–and you freed my soul from prison. You taught me what reality really is. Tonight, for the first time in my life, I saw through the hollowness, the sham, the silliness of the empty pageant in which I had always played. Tonight, for the first time, I became conscious that the Romeo was hideous, and old, and painted, that the moonlight in the orchard was false, that the scenery was vulgar, and that the words I had to speak were unreal, were not my words, were not what I wanted to say. You had brought me something higher, something of which all art is but a reflection. You had made me understand what love really is. My love! My love! Prince Charming! Prince of life! I have grown sick of shadows…

Dorian fires back that she only disgusts him now, that she is nothing without her art, and walks out on Sybil. He goes home to find his portrait has changed, recording his ugliness. He decides to reform but when he finds that Sibyl has killed herself already he abandons himself to every vice imaginable. After 18 years, toward the novel's end he again hopes to reform, but when he checks the painting he finds that its years of accumulated ugliness haven't reversed. This is when he realizes that even his decisions to reform were only made out of vanity and pride, his desire to have the portrait to return to its former beauty. "It had been like conscience to him. Yes, it had been conscience. He would destroy it." Destroying his conscience, he dies.

It's obvious that the George Romney painting of Frances Puleston, the first wife of Bryan Cooke, serves as a proxy for Lolita, the grotesque harm Humbert has done to her, he shooting through it at Quilty (Humbert's double, of sorts) who takes refuge behind it. For Quilty, like Dorion Gray's portrait, serves as Humbert Humbert's conscience to some degree, tormenting him, mocking his professions of love for Lolita. One needs also to consider the portrait as being also a mirror of something interior to Humbert that he has projected onto Lolita, never seeing her for herself, but instead only viewing in her the fantasy he so desires that he cares nothing about taking her prisoner and ruining her life.

Sibyl Vane, so wronged by Dorion Gray, was of interest to Nabokov. In 1951, Nabokov wrote a short story called The Vane Sisters which wouldn't be published until 1958. It concerns a narrator, a French teacher at a girl's school (like Beardsley) reflecting on his relationship with a Cynthia Vane, who he has just discovered to have died. The focus in their relationship was Cynthia's younger sister, Sybil Vane, who had been a student of his. Sybil, in love with another professor and having been abandoned by him, had turned in to the narrator an exam paper foretelling her suicide. The narrator, upon noticing the suicidal footnote, contacted Cynthia, but too late, and then proceeded to grade Sybil's French grammar.

Cynthia is a painter and the narrator is attracted to her art, he's fascinated by the quality of light in her pictures, but he finds her otherwise repellent. Indeed, his description of Sybil's physical appearance reminds a little of the picture of Dorian Gray in that gives her beauty as hidden by a skin disease that marred her features and which she tried to camouflage with make-up and a veil. Cynthia, too, is described with the same attention to her features and complexion depicting her as coarse, unappealingly masculine, covered with dirty make-up/paint. If his descriptions seem arrogant, the story is, after all, about someone who corrected grammar on a suicide note. Eventually, the narrator breaks off with Cynthia when she accuses him of only seeing the gestures and disguises of people.

He initially finds curious Cynthia's preoccupation with signs, synchronicities and seances, the dead communicating even by acrostics, but is eventually repulsed by this fascination as well.

Cynthia...was sure that her existence was influenced by all sorts of dead friends each of whom took turns in directing her fate much as if she were a stray kitten which a schoolgirl in passing gathers up, and presses to her cheek, and carefully puts down again, near some suburban hedge–to be stroked presently by another transient hand or carried off to a world of doors by some hospitable lady.

For a few hours, or for several days in a row, and sometimes recurrently, in an irregular series, for months or years, anything that happened to Cynthia, after a given person had died, would be, she said, in the manner and mood of that person. The event might be extraordinary, changing the course of one's life; or it might be a string of minute incidents just sufficiently clear to stand out in relief against one's usual day and then shading off into still vaguer trivia as the aura gradually faded...

During one of those seances, Oscar Wilde visited and accused Cynthia's parents of "plagiatisme" [sic]. Why does Oscar Wilde condemn Cynthia and Sibyl's parents of plagiarism? The story doesn't say, and doesn't mention Dorian Gray, but this is Nabokov's way of informing us that the Sibyl Vane of his story is to be connected with Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray and his Sybil Vane who died for love of reality over art taught her by the lying devotion of a narcissist who could only appreciate the mimicry of the shadow.

Note that the Sibyl Vane of Nabokov's story commits suicide over a man whose name is only given as D.

The story of the Vane sisters begins like this:

I might never have heard of Cynthia's death, had I not run, that night, into D.,....and I might never have run into D. had I not got involved in a series of trivial investigations.

The day, a compunctious Sunday after a week of blizzards, had been part jewel, part mud. In the midst of my usual afternoon stroll through the small hilly town attached to the girls' college where I taught French literature, I had stopped to watch a family of brilliant icicles drip-dripping from the eaves of a frame house. So clear-cut were their pointed shadows on the white boards behind them that I was sure the shadows of the falling drops should be visible too. But they were not. The roof jutted too far out, perhaps, or the angle of vision was faulty, or again, I did not chance to be watching the right icicle when the right drop fell. There was a rhythm, an alteration in the dripping that I found as teasing as a coin trick. It led me to inspect the corners of several house blocks, and this brought me to Kelly Road, and right to the house where D. used to live when he was instructor here. And as I looked up at the eaves of the adjacent garage with its full display of transparent stalactites backed by their blue silhouettes, I was rewarded at last, upon choosing one, by the sight of what might be described as the dot of an exclamation mark leaving its ordinary position to glide down very fast–a jot faster than the thaw-drop it raced. This twinned twinkle was delightful but not completely satisfying; or rather it only sharpened my appetite for other tidbits of light and shade, and I walked on in a state of raw awareness that seemed to transform the whole of my being into one big eyeball rolling in the world's socket.

D. was the professor with whom Sybil had had the affair. He happened to be passing through town and he and the narrator ran into each other later that evening. After learning of Cynthia's death from D., the narrator becomes anxious that Cynthia might attempt to communicate with him. He both fights against this while also looking for signs sent him by the dead Cynthia.

I plunged into Shakespeare's sonnets--and found myself idiotically checking the first letters of the lines to see what sacramental words they might form...Every now and then I would glance around to see how objects in the room were behaving...my heart would burst if a certain suspiciously tense-looking little bottle on yonder shelf moved a fraction of an inch to one side...presently a crackle (due, I hoped, to a discarded and crushed sheet of paper opening like a mean, stubborn, night flower) started and stopped in the wastepaper basket, and my bed table responded with a little click. It would have been just like Cynthia to put on right then a cheap poltergeist show...

That night he dreams of her, and upon waking he tries to divine any message in the dream.

I lay in bed, thinking my dream over and listening to the sparrows outside: Who knows, if recorded and then run backward, those bird sounds might not become human speech, voiced words, just as the latter become a twitter when reversed? I set myself to reread my dream–backward, diagonally, up, down–trying hard to unravel something Cynthia-like in it, something strange and suggestive that must be there.

I could isolate, consciously, little. Everything seemed blurred, yellow-clouded, yielding nothing tangible. Her inept acrostics, maudlin evasions, theophanies–every recollection formed ripples of mysterious meaning. Everything seemed yellowly blurred, illusive, lost.

The narrator did indeed receive a message. The trick is that the first letter in each word of the above, final paragraph composes an acrostic that reads: Icicles by Cynthia. Meter from me, Sybil. This message refers back to the beginning of the story, the icicles that had so captivated the narrator, and the rhythm of the dripping water that had led him to D's old house and illumined the day for him with a hyper-real awareness. The meter is the parking meter the narrator is standing by when D. comes rolling by in his car.

Christine Raguet-Bouvart writes in Cycnos:

Obviously, at that time Nabokov was preoccupied with the relation between the world of dreams, the unconscious and creation. This is where he comes close to Joyce. Dreams are the manifestation of uncontrolled brain-activity. They escape command and may be felt as links between the realm of the conscious and of the unconscious. They may also encourage some to establish contact between the tangible and the spiritual — an unacceptable inclination in Nabokov's eyes: "I am sorry to say that not content with these ingenious fancies Cynthia showed a ridiculous fondness for spiritualism." Nevertheless Nabokov built this leaning into his story from its very beginning, and illustrated it with a host of allusions to signs, shadows, ghosts and messages, so as to demonstrate how his characters were trying to set up communication with the hereafter. Sybil, whose name recalls the prophetesses of antiquity who could decipher coded messages for human beings, has "a rainbow edge" which reinforces her function as a link, or bridge, between the terrestrial and the celestial worlds, and her bridge is made of words. This obviously recalls Issy's rainbow consort who appears a number of times in Finnegans Wake, but most obviously in Book II, chapter 1: "R is Rubretta and A is Arancia, Y is for Yilla and N for greeneriN. B is Boyblue with odalisque O while W waters the fleurettes of novembrance." Sybil Vane brings men to inaccessible regions, just as the Cumean Sibyl conducted Virgil to the infernal regions (Æneid, vi); therefore she is the guide, the essence of translation. Her presence in these intermediate regions reinforces Benjamin's theory of the presence of auras in works of art as developed by Raymond Court, because divine creation comes to an end when things receive their names from man, thanks to God's gift of language to man. Consequently naming reifies what is named and from then on the name is the symbol of the thing which communicates itself to its environment. In this communication process, man is enlightened and the name, then radiating from the thing, becomes the aura of the thing. This definition can be compared to what Vladimir Alexandrov describes as "Nabokov's epiphanies." Altogether, it would amount to experiencing the essence of absolute communication — within and without, a priviledged moment when self and universal self meet. Besides this may be read as an epitome of the relation between perception, vision and impression found in "The Vane Sisters," which should lead to the knowledge of the universal soul.

If we look at Sybil's name we also find a connection with Dies Irae, a work Kubrick refers to time and again:

Dies irae, dies illa

Solvet saeclum in favilla

Teste David cum Sibylla

The day of wrath, that day

Will dissolve the world in ashes

As foretold by David and the Sibyl!

The narrator of the Vane sisters story is understood as being a double of D., and Cynthia as being a double of Sybil. D. may have not only a connection with Dorian Gray but perhaps David. And what of Cynthia? Rough as this may seem, we need to ignore the true etymology of Cynthia's name and look back to Sybil's description of her love, Dorian Gray, in light of Dies Irae and the world dissolving in ashes. Oscar Wilde's Sybil describes the narcissistic Dorian as her "Prince Charming", language suitable for a fairy tale Cinderella, in which we find our cinders and ash. Cindy is, after all, a nick for both Cynthia and Cinderella.

Our narrator is a professor who teaches French and both Sybil and Oscar Wilde had spoken in garbled French. Icicle (IMHO) is ici - clé or "here key". (Remember this when considering the Clavius portions of 2001.)

Wikipedia notes:

The word "acrostic" was first applied to the prophecies of the Erythraean Sibyl, which were written on leaves and arranged so that the initial letters of the leaves always formed a word.

The narrator in the story is guided all along by Sybil and Cynthia without conscious awareness, and so too are the readers. Nabokov wrote of the story, “My difficulty was to smuggle in the acrostic without the narrator’s being aware that it was there, inspired to him by the phantoms.” He had also to do the same thing with the reader, relying on the inspiration (and acute attention) to conversely bring the reader to awareness. And it's difficult to read Sibyl, to understand her communication. As the story relates:

I plunged into their chaos of scripts and came prematurely to Valesky and Vane, whose books I had somehow misplaced. The first was dressed up for the occasion in a semblance of legibility, but Sybil's work displayed her usual combination of several demon hands. She had begun in very pale, very hard pencil which had conspicuously embossed the black verso, but had produced little of permanent value on the upper side of the page. Happily, the tip soon broke, and Sybil continued in another darker lead, gradually lapsing into the blurred thickness of what looked almost like charcoal, to which, by sucking the blunt point, she had contributed some traces of lipstick. Her work, although even poorer than I had expected, bore all the signs of a kind of desperate conscientiousness with underscores, transposes, unnecessary footnotes, as if she were intent upon rounding up things in the most respectable manner possible. Then she had borrowed Mary Valesky's fountain pen and added: "Cette examin est finie ainsi que ma vie. Adieu, jeunes filles! Please, Monsieur, le Professeur, contact ma soeur and tell her that Death was not better than D Minus, but definitely better than Life minus D."

Nabokov described some of his writing as being such "wherein a second (main) story is woven into, or placed behind, the superficial semitransparent one." In "The Vane Sisters", the description of reading Valesky and Sibyl's papers alludes to this. Valesky is legible. Sybil is very difficult to decipher except for when she borrows Mary's fountain pen.

When The New Yorker rejected the story, Nabokov wrote them:

First of all, I do not understand what you mean by ''overwhelming style,'' ''light story'' and ''elaboration.'' All my stories are webs of style and none seems at first blush to contain much kinetic matter. . . . For me ''style'' is matter.

I feel that the New Yorker has not understood ''The Vane Sisters'' at all. Let me explain a few things: the whole point of the story is that my French professor, a somewhat obtuse scholar and a rather callous observer of the superficial planes of life, unwittingly passes (in the first pages) through the enchanting and touching ''aura'' of dead Cynthia, whom he continues to see (when talking about her) in terms of skin, hair, manners etc. The only nice thing he deigns to see about her is his condescending reference to a favorite picture of his that she painted - frost, sun, glass - and from this stems the icicle-bright aura through which he rather ridiculously passes in the beginning of the story when a sunny ghost leads him, as it were, to the place where he meets D. and learns of Cynthia's death. At the end of the story he seeks her spirit in vulgar table-rapping phenomena, in acrostics and then he sees a vague dream (permeated by the broken sun of their last meeting), and now comes the last paragraph which, if read straight, should convey that vague and sunny rebuke, but which for a more attentive reader contains the additional delight of a solved acrostic; I C-ould I-solate, C-onsciously, L-ittle. E-verything S-eemed B-lurred, Y-ellow-C-louded, Y-ielding N-othing T-angible. H-er I-nept A-crostics, M-audlin E-vasions, T-heopathies - E-very R-ecollection F-ormed R-ipples O-f M-ysterious M-eaning. Everything S-eemed Y-ellowly B-lurred, I-llusive, L-ost. The ''icicles by Cynthia'' refers of course to the setting at the beginning of the story and is a message, as it were, from her forgiving, gentle, doe-soul that had made him this gift of an iridescent day (giving him something akin to the picture he had liked, to the only small thing he had liked about her); and to this, in eager, pathetic haste, Sybil - a little ghost close to the larger one -adds ''meter from me, Sybil,'' alluding of course to the red shadow of the parking meter near which the French professor meets D. You may argue that reading downwards, or upwards, or diagonally is not what an editor can be expected to do; but by means of various allusions to trick-reading I have arranged matters so that the reader almost automatically slips into this discovery, especially because of the abrupt change in style. . . .I am really very disappointed that you, such a subtle and loving reader, should not have seen the inner scheme of my story. I do not mean the acrostic - but the coincidence of Cynthia's spirit with the atmosphere of the beginning of the story. . . .

That's some remarkably acute attention demanded of the reader. I hate acrostics, and as an author I would never do that to a reader, but I well comprehend the attempt to get a reader to divine what is not plainly spoken. Also, the problem with any art is that what one composes is going to be received and interpreted in a very individual way by every reader. So, how to get beyond this, to a degree, and communicate deeply, subtextually, by experience, by (shall we say) style that is matter?

When the narrator of the story sees Cynthia after Sybil's death, and gives her Sibyl's notebook, she held it "as if it were a kind of passport to a casual Elysium". The passport to Elysium is had in Kubrick's work from the beginning, even with Fear and Desire in which lessons learned from The Tempest are used as a gateway, and are invoked in nearly every film of his.

Kubrick borrows from Cocteau's Orpheus in Killer's Kiss with Davey crossing over into the underworld (which I write about in my analysis on the film but may make a separate posting on it). This is all a matter of crossing into the underworld, the place of mysteries, where one receives information in a different and deeper manner. Cocteau had his Orpheus receiving this information as strange radio transmissions in his car. In his play, the transmissions came by way of a horse. They became the source of his poetry, but then he is accused of plagiarism and is killed (refer back to Nabokov having a ghostly Oscar Wilde accusing, in bad French, Sibyl and Cynthia Vane's parents of plagiarism). Some readers think unless the underworld is explicitly mentioned then it's not there. The myth of Orpheus is obviously a trip to the underworld, telling us this is what happening. Nabokov was telling people in "The Vane Sisters" quite plainly there was an underworld current, more than meets the eye. But the story within the story is not always announced. Which is something one could say all about all art, and one's daily life, which is one of the points to the story of "The Vane Sisters".

I'm going to back up a little and return to Shakespeare, how the narrator of the story of Sibyl and Cynthia Vane had endeavored to find a connection with Cynthia by looking at Shakespeare's sonnets for acrostics but had come up with nothing meaningful.

Nabokov liked to talk about how he shared Shakespeare's birthday and he transferred some of this over to the playwright, Quilty. Two license plates that Quilty has on his cars that follow Humbert Humbert have the birth and death years of Shakespeare. Quilty is thus associated with Shakespeare in the novel, and Kubrick satisfies that association by placing the Shakespeare bust in Quilty's mansion in the movie.

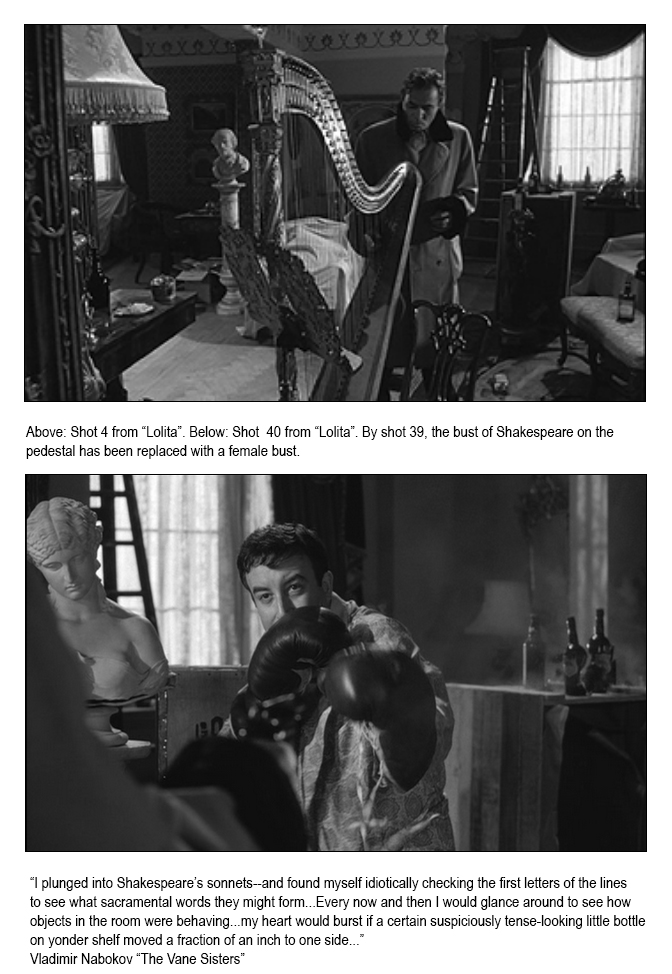

Kubrick moves things around in his films, exchanges out objects, and does other subsurface tricks that I look upon this as a kind of dialogue with the viewer, just as the narrator of "The Vane Sisters" describes when wondering if an object has moved and if it was a communication from Cynthia or Sybil--Nabokov's story within a story. In the opening section of Lolita, there is quite a bit of movement of objects that plays in with the chaotic energy of Quilty. The portrait through which Humbert guns down Quilty, at the height of the second story stairs, is so anxious to get in on the action that it moves from its original placement, near the front door, to the height of the stairs as Quilty finishes ascending them. It refuses to stay in its original place on the first story. It ascends to the second. And, yes, I am emphasizing the idea of the portrait's participation in two stories. Another notable change is a bust of Shakespeare is traded out with another, which is a reason I brought up Shakespeare and Quilty's license plates and have written so much on "The Vane Sisters" , due the narrator (futilely) researching Shakespeare's sonnets for messages. And yet he was looking for an acrostic, and it is a hidden acrostic that finishes out the story.

I'm of the camp that believes no one knows what "Shakespeare" really looked like, but the bust of him used is from the 18th or early 19th century, done after Louis Francois Roubilliac, based on the Chandos portrait. That bust is replaced with what is known as the bust of "Clytie", due to a Charles Townley having named her as such, but is believed to be perhaps of Antonia Minor in the guise of Ariadne. This bust was very popularly copied during the 19th century, but it's still interesting to me that Kubrick chose this particular one to replace Shakespeare, and that we seem, in a way, to have her opposing the Romney portrait, separated by the area in which the ping-pong table is situated that is surrounded by a Greek Key design, a meander border associated with the labyrinth. Ariadne? She is the one who provided Theseus the clew by which to navigate the labyrinth.

Humbert claims in the novel, his memoir, that he uses Lolita's real first name, but that he has veiled her identity with her last name being fake. Haze. He states, however, that the last name rhymes with her real name. Though never explicitly stated, we are able to tease out of the book that this last name would be the equivalent of maze (maybe Mayes).

I think it's unlikely that Kubrick selected Romney's portrait for no reason at all other than having found it attractive.

In the next section and last section of this post I'll explore several other movies that tie in with the painting and a significant other one that is only partially disclosed in the film but to which Kubrick returns in Eyes Wide Shut, displaying in full.

Return to top

Kubrick, throughout his work, insists upon the viewer being confronted with the problem of the creator versus the created, the artist and the muse, this implied in the very opening scene of the man's hands painting a young woman's toenails, he being her painter, Humbert being the painter of Lolita, Nabokov being the painter of Humbert and Lolita, which underlies the significance of the Romney portrait in the film.

Though the movie begins with a toe nail painting scene, and we have another one at Beardsley which is a different scene than the opening one, Humbert Humbert doesn't paint Lolita's toenails in either Nabokov's book or screenplay. The painting of the toenails would then be all Kubrick, and something which he considers to be of importance enough that he begins the movie with the toenails being painted, but those shots don't belong to the action at Beardsley. We can't even be certain that the opening scene of the painting of the toenails is of Humbert and Lolita. It may well be instead another older man and another young girl, another painter and his young muse. That young muse tends, throughout history, to be gloriously, romantically sung about and represented, but is often the subject of abuse. A book I was reading about Barrie, the problematic author of Peter Pan, highlighted the abuse of young models by their painters in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. How the women were prostituted, taken advantage of. How there was, at the time, a trend for hypnotizing them so they might sit for long stretches as they were painted, and the harsh physical and mental tolls this exacted. How painters became rich off their paintings of their muses, who they had left behind, who did not benefit from these profits and would die penniless, before their time. The portraits that Romney did of Amy Lyon as different mythological beings were calculated to bring wealth, but none of that wealth would benefit the muse. Society accepted these muses as vacant mediums having no value in and of themselves but for what was impressed upon them by the artist. These were women who were made to be possessed for a time then let back into the wild when inspiration was done with them.

The opening scene of the toenail painting is overlaid with thick romantic music, and has a soft glamor. The second scene of the painting of the toenails has an adolescent teen, who is virtually imprisoned by her abuser, ping-ponging back and forth between behaving as a teen stretching for some independence in a grotesque situation that masquerades as a father-daughter relationship, and resorting to seduction as a persuasive technique, which doesn't work. It's not a glamorous, romantic situation. Love has no play here. Possession, isolation and secrecy is all.

The toenail painting was a not-yet puzzle piece that became a resolved one when I happened to be watching Fritz Lang's Scarlet Street starring Edward G. Robinson and Joan Bennett. In the film, there's a scene in which Robinson was painting Bennett's toenails, and the temperament of it is such that I went, "A-ha!"

Robinson plays a cashier who is also an unsung artist whose works have never been seen by anyone other than himself and a wife who is presented as your classic harpy figure. He's a passive, reticent man in whom some jealousy is stirred when, after twenty-five years of service to his employer, he's given a gold watch, but then the employer leaves with a young woman, which is what Robinson really wants, the love of a young girl. Opportunity strikes when on his way home he runs into a woman (Joan) who is being attacked by a man. He comes to her aid, helps her home, she gets the idea he's wealthy, and she opportunistically becomes his mistress. He sets her up in a nice household, even stealing from his employer to keep her in style. As it turns out, the man who was beating Joan was her boyfriend, and remains her boyfriend, essentially a pimp, and they both mock Robinson's love for her. When Robinson wants to paint her, she offers him her foot instead, and as he devotedly paints her toenails she says each one will be a masterpiece. Money starts to dry up so the boyfriend sells some of Robinson's paintings for a few dollars, but then a critic notices them and Joan is convinced by the boyfriend to pretend she is the painter. Robinson has no problem with this, as it turns out. He's fine with letting Joan serve as his face, he says it's all like a dream. Joan parrots Robinson's words about painting so that she is believable as a painter, though she is also said to be like two people due the conflict of the words with her personality, and rakes in the money and recognition. She now agrees to Robinson painting her. He says it will be called a "self portrait". In the meanwhile, Robinson's wife's first husband, who was believed to be dead, shows up. Robinson runs to Joan to tell her he can be with her as his marriage is invalid, discovers her with her boyfriend, and ends up killing her. The boyfriend is accused and no one believes any of his stories about Robinson and how he is the one who was the painter. The boyfriend is convicted. After he is put to death, Robinson attempts to hang himself. He's rescued but his life is now in ruins. The last scene has him as a bum sleeping on a bench. Police rouse him, and as he walks down the street he sees a portrait he'd painted of Joan in a window. It's Christmas and "Oh come all ye faithful" is playing. It's a "masterpiece" that was just sold for $10,000.

Scarlet Street is Lang's redo of Jean Renoir's film La Chienne. In Renoir's film, the woman with whom the painter becomes involved is a prostitute and her boyfriend is a pimp. At the end of that film, the painter is without money, a bum, but isn't tormented like Robinson. The "masterpiece" in the window is his own self-portrait, not of the woman. When it's carried out to a car, having been sold, he follows to look at it, and is given a few francs. He happily tells a friend life is beautiful and will treat him to dinner.

Scarlet Street is a follow-up to Lang's The Woman in the Window in which Robinson played a psychology professor whose wife goes on vacation, he becomes enamored of a portrait of a woman in a window, talks with some men at a club about mid-life crisis and the tragedy that can follow a dalliance, sits down to read "The Song of Songs" at the club, meets the woman in the painting, gets in a lot of trouble, overdoses, and just when you think he is dying he wakes up to find it was all a dream and he is still in his chair at the club. Dream or reality is the question in Eyes Wide Shut.

There's an important sliver of a painting viewed in this nail painting scene that actually reappears in Eyes Wide Shut.

You can barely make out Modigliani's famous painting of Elvira hanging above the bed..

Kubrick revisits the painting, showing it in full, in Eyes Wide Shut.

Information about Elvira is difficult to come by and conflicting. She was a dancer, I guess also a prostitute, daughter of a prostitute. She ran away from home at 15. I don't know at what age she was hooked up with Modigliani but from what I've read it must have been after she was 20. Her nickname was "Quique". Quique means Enrique which is Henry? Some wonder if Quique wasn't supposed to be for "chica". If Kubrick knew of the nickname, Quique, may we have had in that nickname another reference to Quilty, whose nick is Cue/Que. Elvira is a name of perhaps Spanish origin that may have meant "white" but is most frequently given as meaning "true". In a cigarette ad showing Quilty in Lolita's bedroom, the text reads, "DROME for real true taste".

Elvira's appearance in Eyes Wide Shut occurs between Bill's visit to the Rainbow costume shop where he sees the Lolita-like daughter of the shopkeeper a second time, and the two Japanese men with whom she had been the previous evening. He suspects she has been prostituted by her father, and it seems that her father offers the girl up to Bill though this is only implied. Bill goes to his office after this, then cancels his appointments and heads out again to Somerton where he will be told to cease his quest to learn what happened to the woman who took his place the previous night. By redeeming Bill, Amanda has become his proxy. In Lolita, examining the film we can see how when Humbert shoots Quilty through the portrait of the young woman, though it would seem he is shooting a symbol of Lolita behind which Quilty takes refuge, he is also symbolically shooting himself. Quilty's taking refuge behind the painting also enables us to make an association between himself and her, the woman's face becoming as a mask over his own or vice versa. It doesn't matter which. They are all parts of Humbert and signify some primal damage to Humbert that has to do with his uncle, Gustave. We are never told what this is. We only know he is haunted by this uncle, a relative of his father's, who was once married to his mother's older sister, Sybil. After the death of his mother, Sybil stepped up and helped Humbert's father to care for him.

My mother’s sister, Sybil, whom a cousin of my father’s had married and then neglected, served in my immediate family as a kind of unpaid governess and housekeeper. Somebody told me later that she had been in love with my father, and that he had lightheartedly taken advantage of it one rainy day and forgotten it by the time the weather cleared.

The hands of Elvira, in the Modigliani painting, are the only part shown in Lolita, and thus provide an easy link to the subsequent scene in which Quilty poses as the psychologist who presents himself as colluding with Humbert to keep the school psychologist from investigating Lolita's home situation as long as Humbert allows her the freedom to be involved in what will turn out to be a play by Quilty. Unknown to Humbert, Quilty is waiting for him in the sitting room. When Humbert opens the door on it, all that we at first see of Quilty are his hands.

After this, we view Lolita in the theatrical, and if one considers her heavy stage make-up it may seem she has become as a painting, so it is significant that we were recently shown Humbert painting her toenails. He is the portrait artist, and what has he created?

Vivian Darkbloom is mentioned by Lolita in the toe-nail painting scene, and though we see her several times in the film I believe this is the only time her name is revealed. She is given as an author of the play being presented, along with Quilty. Her name is an anagram for Vladamir Nabokov, so we have the author's feminization of himself, which fits with the young muse, in Scarlet Street and La Chienne, taking on the artist's identity, becoming his public face.

The repeated factor with most of these movies and stories of artists and their muses is the young woman or girl who either comes under the dominating figure of an older man who sets out to mold her, or who enters prostitution at a young age and is used and abused. The pianist in The Seventh Veil has skill but Mason claims that he created her and will not let her go. In the end, she supposedly having graduated into being her own person, his domination is rewarded by the movie interpreting this as love, her recognizing it as such, and choosing him as her partner. The women in Scarlet Street and La Chienne are presented as thanklessly refusing absolute rescue from their pimp by this passive but jealous cashier who is given as dominated and used by his mistress. Their stories are of individuals who at first one might have sympathy for as we are introduced to them when they are beaten, but when the audience is shown the women only have love for their pimps and are using the painter at the behest of their pimps, the audience loses sympathy. They become femme fatales who are murdered for using and laughing at the poor sap who, supposedly, truly loves and cares for them (yet he is the murderer). The movies make it hard to have sympathy for these femme fatales, despite the power differential and the fact we first see them when they are beaten, and then end with their supposed rescuer murdering them. Consider how Humbert perceives and presents the young Lolita as a femme fatale, but he is an untrustworthy narrator, and it's always easy, in the novel, to read between the lines that what he imagines is not reality and what he enjoys is his power over the child, to ruthlessly make her do whatever he desires. The problem we encounter is the portrayals of women, these muses, have throughout history been done by men, women considered as nothing more than sex objects, breeders and caretakers in patriarchal society, so how much are we actually seeing of the muses, aren't we instead viewing the men and how they see the women.

Kubrick, with Humbert painting Lolita's toenails, makes him the painter of her portrait, of her, but Humbert is also doing his own self-portrait in how he paints and represents the girl. We know this in the book, but it was another thing to communicate it in the movie. Lolita can't even properly see herself. She apologizes to Humbert at the end, says she's sorry for having "cheated" on him, and sprightly offers to "keep in touch" with this man who daily raped her. Not even Lolita has any idea what was done to her and looks upon herself as having "ruined too many things in my life". Lolita has never even told her husband, Bill, about Humbert. Humbert's abuse is instead her stain and a secret she must burden. It is both poignant and pathetic, that at film's end Lolita reaches out to Humbert for help, because this rapist is the only family she has left, not even comprehending she should be owed anything from her mother's estate. Poignant and pathetic that she would want to keep in touch, because he is the only family from childhood she has left, and is grateful to him for simply giving her what's her legal due.

UPDATE NOVEMBER 2020: John Cork, who knows all things James Bond (an interesting subject), sends along some humorous information on the painting that he picked up along the way. And it seems the painting that Kubrick originally had in mind ended up not being the portrait that was used. I've placed it under the subject heading of the portait in the first page of the analysis.

April 2018 extracted from analysis and expanded upon. Approx 9600 words or 20 single-spaced pages. A 72 minute read at 130 wpm.

Go to Table of Contents of the analysis (and supplemental posts)

Link to the main TOC page for all the analyses