KUBRICK'S LOLITA

A SHOT-BY-SHOT ANALYSIS

PART ONE

Go to TOC for this film ( (which has also a statement on purpose and manner of analysis and a disclaimer as to caveat emptor and my knowing anything authoritatively, which I do not, but I do try to not know earnestly, with some discretion, and considerable thought).

A NOTE ON THIS ANALYSIS. I COMPARE, SCENE BY SCENE, AT THE END OF EACH, KUBRICK'S FILM WITH NABOKOV'S SCREENPLAY. I HAVE ALSO UNDERLINED THAT DIALOGUE WHICH IS FROM THE NABOKOV SCREENPLAY BUT WHICH IS USUALLY PARAPHRASED. DIALOGUE IN THE FILM WHICH WAS IN THE BOOK, BUT NOT IN THE SCREENPLAY, MAY BE UNDERLINED BUT IS OFTEN INSTEAD OUTLINED IN THE COMPARISON SECTION OF EACH SCENE.

James Mason - Humbert Humbert

Shelley Winters - Charlotte Haze

Sue Lyon - Lolita

Peter Sellers - Clare Quilty and Dr. Zempf

Gary Cockrell - Richard T. Schiller

Jerry Stovin - John Farlow

Diana Decker - Jean Farlow

Lois Maxwell Nurse Mary Lore

Vladimir Nabokov - Screenplay and novel

Nelson Riddle - Music

Oswald Morris - Director of Photography

Anthony Harvey - Film Editing

William C. Andrews - Art Direction

USA release date 13 June 1962

For complete listing see IMDB.

This work followed two years after Spartacus, putting Kubrick at about thirty-four.

TOC and Supplemental Posts | Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Films Home

LINKS TO SECTIONS OF THE ANALYSIS ON THIS PAGE:

Prologue. Shot 1. Rachmaninoff and James Mason in The Seventh Veil.

At Long Last, Humbert Finds Quilty. Shots 2 through 63.

Shots are commented on in the section. Remarks on the entry, on comparing the entry to the end of The Shining. On ping-pong and Captain Love. Quilty as magician. Brewster. Some set changes such as replacing a Shakespeare bust with that of a woman. People as furniture and A Clockwork Orange.

Comparing Kubrick with Nabokov

The Portrait. Further elaborated on in Portrait of Lolita, an Analysis of the Shooting of the George Romney Painting

Location

Cycles. The beginnings and endings of Kubrick's films.

The Romney Portrait, the Statue of the Spartan Warrior and the Woman, the Statue with the Shoe, the Harp, that Table Tennis Game, and the Swapping of Shakespeare for the Bust of Ariadne who Provided the Clue for the Minotaur's Maze

On Quilty, Nabokov, and Vivian Darkbloom. An exmination of Quilty's and Vivian Darkbloom's names.

The Enlarged Role of Vivian Darkbloom and Fate

July 4th, Spartacus, and The Shining

On Mazes and Minotaurs

From 2000, Some Thoughts I First Wrote on Lolita. In which James Mason and Shelley Winters beat Lucy and Desi into the ground with baseball bats, then hop up and down upon their comedic graves.

Clare Quilty, The Chair

Into the New World, an Old World Refugee

The Monster Emerges

The Great Partner Swap

Don't Forget Me

A Case of the Asiatic Flu

The Mother

1 Credits (00:15)

CU. Credits with romantic music, piano rolls and orchestral crescendos highlight with syrupy, soap opera drama the painting of Lolita's toenails, wedding band on the supposed Humbert's left hand that supports and offers her fetishized foot for the camera, in its delicate professionalism also reminding of a spa technician tending a client. Fade to black from 2:03 to 2:07.

I was presented with a possible Lolita puzzle piece--one of those puzzle pieces you don't realize is a puzzle piece until you stumble onto it--when Too Young to Kiss was playing on TCM. The story concerns a 22-year-old pianist who, having been unable to meet with a promoter, learning that he will be at an event for young talent, passes herself off as a 12-year-old and finally gets a hearing. He (Van Johnson) is wowed by the 30-something June Allyson in pigtails and brightly polished Mary Janes and promises her an amazing career. When June presents herself as the 12-year-old's older sister, hoping to transfer Johnson's enthusiasm to her own skills, Johnson takes a disliking to her, an antipathy that intensifies when he later sees the 12-year-old "Molly" smoking and drinking alcohol. Molly's older sister is a bad influence! So Van whisks Molly off to his estate in the countryside where he will reform her, give her a good spanking, and prepare her for her career as a concert pianist. Van also ends in reforming himself as well through the introduction of Molly to the pleasures of bike riding and amusement parks. The stellar moment of the film occurs after Van declares his desire to adopt her, thinking of her as a daughter, then challenges her to a race to the dinner table. "Last one in is a rotten egg." It's pretty funny, actually. Then Molly goes and ruins the family vibes that night by planting a kiss on him. Van realizes he's been had just prior Molly's concert, introduces her as a great talent anyway, then stands about watching her play from different angles in the concert hall. Of course she loves him, and he realizes as he watches her play Grieg's Concerto in A minor that he loves her, but is conflicted. The film ends with them getting together, of course.

While I was watching, I don't recollect at what point, I suddenly had, for a split second, a moment of Kubrickian Lolita deja vu. One might think this kind of film would be all creepy Lolita vibes, but despite the danger zone it wasn't. Certainly, though this is a parody, we have still the trope of the mentor/guardian linking up romantically with the young protege, but June and Van handle it well. I've never cared much for either Van or June but I rather liked them in this, June doing a weirdly able job of pretending she was 12, aided by her height (very short) and the fact she has no sex appeal whatsoever in any film I've ever seen her in. Pigeon-toed and tied up in pinafores, smoking and drinking and bullying Van when he makes her give up her bad habits, she's kind of fun. Van's transition from seeing her as a child to viewing her as a woman occurs during the concert hall scene toward the end. I wondered why so many minutes were being expended on the scene, Van moving all over the hall to view her from different angles, then realized it was the film's way of providing space for Molly to transition to an adult in Van's eyes, providing time for the audience to move to viewing them as an adult couple as well. Anyway, it was at some point either during that scene or after it that I had the moment of Kubrickian deja vu.

Was it the music? I wondered if I began to feel that deja vu ping when June was playing the Grieg concerto? No, the Grieg didn't remind me of Lolita but something else about the scene did. I looked up the Grieg Piano Concerto in A Minor anyway and found that back in 1945 James Mason (yes, Humbert Humbert of Lolita) was in a film called The Seventh Veil and the Grieg piano concerto was featured in that. What was the film about? Well, it was about another child-adult romance, in this case a wealthy, young misogynist becoming ward over his young 2nd cousin and whipping her into shape to be a concert pianist. He's not like Van. He's a mean, possessive guy. As she becomes older, she falls in love with a man, and he refuses to let her marry him. Later, she falls in love with someone else, in response to which Mason threatens to break her fingers while she is playing the piano, crashing his cane on the keyboard. She flees. A too convoluted plot eventually has her dipping into her past memories, via hypnosis, to find her way to the roots of some trauma, by which process she discovers she loves her guardian, but it's by now quite all right as she's of age. The two scenes that strongly resonate between Too Young to Kiss and The Seventh Veil are the concert ones--Van watching June playing the Grieg in concert, and Mason watching his now adult 2nd cousin playing Rachmaninoff's Piano Concerto 2 in C Minor. As with Van, it's a transitional point for Mason in his relationship with his cousin, much time spent on her playing and his face as he watches her, we being informed that he is now obviously in love with her. At film's end, the pianist must choose between several men--a modern band conductor, a man who Mason commissioned to paint her portrait, or Mason. Of course we know who wins. The abusive former guardian, who was only so severe with her because he loved her. She flies to his tortured arms and the film ends with the audience believing this couple will live happily ever after.

At the end of the Rachmaninoff, James Mason looking on, the Kubrick deja vu struck, a dramatic, ascending chord progression being much the same as a central one in the Lolita Love theme by Nelson Riddle. And when I looked up Rachmaninoff and Riddle I found that others were noting the heavy Rachmaninoff influence on the piece, but none mentioning this concerto specifically or its role in The Seventh Veil film.

That this particular piece by Rachmaninoff was used in The Seventh Veil film, in which hypnosis strongly figures, likely has to do with this concerto being dedicated to Rachmaninoff's hypnotist. Yes, he had a hypnotist. He went through such a profound writer's block that he tried hypnosis, found it successful and wrote this concerto.

As it turns out, Rachmaninoff and Nabakov had an association. It's given as minor but it was a huge one relative Nabakov's career. Rachmaninoff, hearing of Nabakov, feeling an affinity to him (you're a Russian, I'm a Russian, etc.), gave him $2500 to move from France to America and start a new life. Interestingly, in Nabokov's Lolita, when Humbert gives Lolita the money to move to Alaska and begin a new life, he gives her $400 in cash and a check for $3600. In Nabakov's screenplay, he gives her $400 in cash and a check for $9600. However, in the movie, he gives her $400 cash and a check for $2500. A coincidental fluke, or an intentional reference, Kubrick having Humbert give Lolita a check for her fresh start elsewhere that is the same amount that Rachmaninoff gave Nabakov to have his fresh start in America? We will learn that Quilty, too, is preparing to move to England. In the book, he insists he has no money and will have to borrow "like the bard (Shakespeare) said"".

The chord progression between the Lolita love theme and Rachmaninoff's 2nd piano concerto--and the emotional, crescendo drama effect of it--does lead me to believe that Nelson Riddle was referencing that concerto specifically, and thus The Seventh Veil as well, in which Mason becomes a tyrant of a guardian and eventual lover to his young cousin. But, then again, this may be all simple coincidence.

At the link is a post dedicated to Portrait of "Lolita", an Analysis of the Shooting of the George Romney Painting, exploring the relationship of the painting of the toenails with the portrait of the young woman through which Humbert will shoot Quilty. The first section of the post is dedicated to discussing the above at greater length.

2 LS. Fade in on foggy road, a car traveling away from us. (02:10)

Light in color, the car almost disappears into the fog in the distance.

3 LS. Quick crossfade to the station wagon pulling up a long drive. (02:18)

We see Humbert in the driver's seat.

Shot 2 | Shot 3 |

|  |

4 Crossfade from car to an establishing shot of the interior of the mansion. (02:28)

Crossfade from the car approaching the mansion to its interior that materializes out of the trees. Later, the idea of the enchanted hunter becomes a theme in the film, and one may find perhaps a hint of an enchanted forest here. The crossfade ends at 2:29 with a harpsichord flourish. A particular outstanding tree dissolves away revealing a statue on a box with a woman's high heel shoe on its head. In the 60s, and even now, this would have signaled decadence. A careless woman left a shoe behind after a night of drunken hedonism. Somewhere, making her way home, she hobbles along with one bare foot.

In the image above, the ghostly figure exiting the frame, screen right, is said to be Kubrick making a cameo appearance. I don't know if it is Kubrick, but if it is then it's perhaps interesting he left here this ghostly trace of himself. One might watch a number of times and miss this detail, then see it and once seen it is something that is plainly visible. How could it be missed on the big screen?

Kubrick exits screen right, Humbert's shadow upon the front door in the background.

The entry is in disarray with what seems the aftermath of a party and moving preparations. An endless number of emptied bottles of alcohol lie about and overturned glasses litter the floor. Glasses and bottles fill the tops of BOELENS packing boxes. Large portraits, dissociated from the walls, wait to be packed or stored. White coverings drape the furnishings to ghostly effect.

The door opens and Humbert (James Mason) enters with more suspenseful harpsichord flourishes. He knocks over glasses and bottles as he walks, passing a white draped chair.

One could hazard that with the almost raucous array of design styles in the room, and the numerous packing boxes, we might be reminded of the mansion of Charles Foster Kane in Citizen's Kane and his obsession with collecting, his acquisitions forming a haphazard, grotesque museum of culture through the centuries.

The Addams Family, based on New Yorker cartoons, had yet to make it to television (1964) but one may also feel a certain shared DNA between the Addams mansion and this one (aided by the harpsichord), perhaps like fourth cousins meeting and noting they have the same chin, though it and the webbed toes could have come down a completely different, unshared family line.

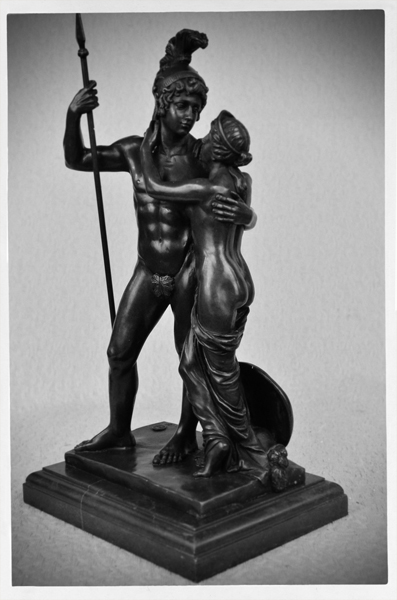

As Humbert enters the sitting area from the entry hall, the camera follows revealing even greater disarray. We see a bronze statue of a Roman/Spartan warrior with a woman clinging to him, a sandwich speared on his lance. Humbert passes a bust of Shakespeare that gazes at the camera, a harp which he strums. A ladder rests next a window. Moving along between the harp and a piano, he steps back out into the entryway. He calls for Quilty.

Note the word play--the Shakespeare bust preceded by the Spartan warrior with his spear accentuated by a sandwich.

At the film's end, Kubrick will repeat this scene and we will believe we are seeing it exactly reduplicated when it is not. Though the scene at film's end will be almost exactly as this one, it is not the same take and there will be a couple of notable differences.

Shot 4 | Shot 4 |

|  |

HUMBERT: Quilty? Quilty?!

The pavement of the hall floor is decorated with a Greek keyhole design, a meander that traditionally recalls the twists and turns of a labyrinth. We should be reminded of the last scene in The Shining in which we see the furnishings of The Overlook's lobby clothed in white drapings as the camera zooms in on the old photo in which Jack will be revealed. The Shining had also a maze.

In the background, a dark bottle falls from its balance near the top of a draped chair, knocking against a clear bottle on the seeming lap of the chair, but then Quilty (Peter Sellers) emerges from beneath the sheet and we have the effect of Quilty assuming himself out of the chair and the white sheet, as if a spirit. The bottle that had seemed to be balancing toward the chair's top instead had been precariously perched atop Quilty's head.

Quilty being a chair will relate to later dialogue about people who can be used as pieces of furniture.

QUILTY: Wha...what? What was that?

HUMBERT: Are you Quilty?

QUILTY: No, I'm Spartacus. You come to free the slaves or something?

Quilty stands, the drapery becoming a toga in keeping with this reference to Kubrick's previous film, Spartacus.

HUMBERT: Are you Quilty?

QUILTY: Yeah, I'm Quilty. Yeah, sure.

The toga becomes caught on a box and pulls it over. Quilty shakes a disapproving finger at it.

Humbert slips on his gloves.

QUILTY: Hey, you, uh, what you putting your gloves on for...?

5 MS Humbert putting on gloves. (03:58)

Cut to James Mason with a clock behind, the ping pong table net before him, separating him from the camera.

QUILTY (off screen): ...Captain, your hands cold or something?

HUMBERT: Shall we have a little chat before we start?

Quilty has called Humbert "captain". When Humbert attempts to get lodging at the Enchanted Hunters Hotel with Lolita, he is told they are full. Then it is reported that a Captain Love has cancelled his reservations, which provides a room for Humbert and Lolita. As Quilty is standing nearby at the hotel's reception desk, listening to the conversation, it seems reasonable that he calls Humbert "captain" here in reference to this. Also, during the ping-pong "game" that follows, we have a statement of "love" used in scoring. Yet in a few moments Humbert will wonder, with some surprise, that Quilty honestly doesn't appear to recollect him.

At the beginning of a tennis game the score is love-love, love meaning nil in the case of tennis scoring. No one knows how the use of "love" came about. It's theorized perhaps through the idea of something done for "the love of" it, no stakes being wagered. Others say it may have to do with l'oeuf, French for egg, and zero resembling an egg.

Humbert associated with Captain Love, and love being used for the scoring (there is no ping pong game in the book) I think it's possible this game references the idea of whether or not Humbert really does, as he protests he does, realize ultimately that he loves Lolita. I go into this elsewhere, but Nabokov's book was described by a critic named Lionel Trilling as a great love story, and Kubrick in interviews for the film would reference Trilling and reasons he gave for it being a great love story. Nabokov does have Humbert declaring that in the end he realized his love for Lolita, but Nabokov also leaves it up for us to determine whether or not he did love her, and we must take into account how Humbert's an unreliable narrator and gives only slight asides to the trauma she experiences at his hands, Lolita kept his literal prisoner. Nabokov never makes us once feel that Humbert is in love with Lolita when she is young. He makes apparent Humbert's sadism and the great harm done to Lolita.

Quilty is as an alter ego of Humbert's and in the film Quilty carries on a game of tormenting Humbert, following him, provoking him, a presence that ever threatens to reveal Humbert's abuse of her, then finally steals her away though he feels and feigns no love for her. If one can look at this as a game played by Quilty, then we find it in the ping pong game, which prefigures the story that has already ended. I cover this topic at great length in the post The Problems with Discussing Lolita.

The reason for the game of ping pong is also discussed in a section below, The Romney Portrait, the Statue of the Spartan Warrior and the Woman, the Statue with the Shoe, and the Swapping of Shakespeare for the Female Bust. Believe it or not, it involves the statue of the woman with the shoe on her head and how it relates to a game of tennis in the novel and Priapus.

6 LS Quilty from behind and right of Humbert. (04:03)

QUILTY: Before we start? Wow, all right. All righty. No, no, listen, listen, listen, let's have a game, a little lovely game of Roman ping pong (picking up paddle and ball) like two civilized senators. Roman ping.

A "little, lovely" game. We will be reminded of this later at the Enchanted Hunter's hotel when Quilty, playing the policeman, queries Humbert on the lovely little girl with him.

Quilty bats the ball toward Humbert.

Shot 6 | Shot 7 |

|  |

7 MS Humbert from beyond the net. (04:22)

QUILTY: You're supposed to say Roman pong.

8 MS Quilty from beyond the net. (04:29)

QUILTY: Okay, you serve. I don't mind. Uhm, I just don't mind. Come on.

Shot 8 | Shot 9 |

|  |

9 MS Humbert from beyond the net. (04:37)

10 MS Quilty from beyond the net. (04:39)

He produces from under the sheet another ball and waves it at Humbert.

Quilty has the air of the magician to him, producing the ping pong balls from beneath the sheet. Kubrick's works are permeated with a sense of magic. His first feature film, Fear and Desire referenced Shakespeare's The Tempest, in which Prospero, a magician, dramatically manipulates perceptions of reality with his magic. The final section of his last film, Eyes Wide Shut, began with the camera's eye passing over boxes of the Magic Circle magic set in the toy store.

Shot 10 | Shot 11 |

|  |

QUILTY: Ahhh. Bet you didn't know I had that. Roman ping pong.

He hits the ball at Humbert.

11 MS Humbert from beyond the net. (04:59)

The ball bouncing toward him, he lets it fall off the table.

12 MS Quilty from beyond the net. (04:52)

QUILTY: Hah. Kind of tricky serve to handle, heh, Captain? Kind of tricky. One of the champs taught me that.

Shot 12 | Shot 13 |

|  |

13 LS of Quilty from behind and right of Humbert. (04:59)

He pulls out another ping pong ball from beneath the sheet.

The music has slowly, unobservedly faded out.

QUILTY: My motto is be prepared.

He paddles the ball to Humbert who listlessly hits it back, the ball bouncing off the net.

14 MS Quilty from beyond the net. (05:09)

QUILTY: Say, you Jack Brewster? Are ya?

He hits yet another ball.

Later in the film, after the performance of The Enchanted Hunters, we will learn Brewster is an assistant of Quilty's whom he sends out for some Kodachrome A.

15 MS Humbert from beyond the net, swings at the ball and misses. (05:11)

HUMBERT: You know who I am.

16 MS Quilty from beyond the net. (05:13)

QUILTY: What's that? That's uh 3, 3 love. Gee, I'm really winning. You wanna get a rally going.

17 LS of Quilty from behind and right of Humbert. (05:20)

QUILTY: You know, I'm not accusing you, Captain, but it's sort of absurd the way people invade this house without even...

He paddles another ball at Humbert who again swings and misses.

18 MS Quilty from beyond net. (05:28)

...knocking. 4 1. Change service. I'll take the service again if you don't mind.

Pulling another ball out from beneath the sheet.

QUILTY: I sort of like to have it off this end. You know.

He hits the ball and Humbert hits it back.

19 LS of Quilty from behind and right of Humbert (05:41)

QUILTY: They use the telephone...

He hits the ball and it strikes a glass, PING.

Shot 14 | Shot 15 |

|  |

Shot 16 | Shot 17 |

|  |

Shot 18 | Shot 19 |

|  |

20 MS Quilty from beyond net. (05:45)

QUILTY: Geez. What's that. It must be a...gee, I'm really winning here. I'm really winning. I hope I don't get overcome with power.

He's produced another ball from beneath the sheet.

QUILTY: That's about 6 1 maybe. Let's say 6 1, no 6 2, I'll give you another point. 6 2 but I'm still winning.

Strikes the ball.

21 MCU Humbert. (06:00)

HUMBERT: You really don't remember me, do you?

Shot 20 | Shot 21 |

|  |

22 MS Quilty from beyond the net. (06:04)

QUILTY: If you haven't noticed how the champs, different champs use their bats, y'know some of them hold them like this...

He changes his grip so the thumb is on one side of the paddle and fingers the other.

QUILTY: ...and everything.

23 MS Humbert from beyond net. (06:12)

HUMBERT: Do you recall a girl called (examining his bat) Delores Haze?

24 MS Quilty from beyond net. (06:20)

QUILTY: I remember one guy, he didn't have a hand, he had a bat instead of a hand, he was a real sort of whacky...

Humbert knocks the table twice, off-screen.

25 MCU Humbert. (06:24)

HUMBERT: Lo-li-ta!

Shot 22 | Shot 23 |

|  |

Shot 24 | Shot 25 |

|  |

Shot 26 | Shot 27 |

|  |

Shot 28 | Shot 29 |

|  |

26 MS Quilty from beyond the net, pulls another ball from the pocket of his bathrobe. (06:26)

QUILTY: Eeuh. Lolita. (A look of recognition.) Yeah, yeah, yeah. I remember that name, all right. Maybe she made some telephone calls. Who cares?

He hits 4 balls at once.

QUILTY: Gee.

His eyes widen, looking at Humbert.

27 MCU of Humbert holding a gun. (06:42)

28 MS Quilty from beyond the net, eyes focused on the gun. (06:44)

QUILTY: Hey, you're a sorta bad loser, Captain. I never found a guy who pulled a gun on me when he lost a game.

29 LS Quilty from behind and right of Humbert who holds the gun on him. (06:54)

QUILTY: Didn't anyone ever tell you, it's not really who wins, it's how you play. Like the champs.

He places down the paddle.

QUILTY: Listen, I don't think I wanta play any more. I wanta get a drink.

Turns from the table.

30 MS Quilty with Humbert beyond. (07:08)

The camera pulls back as Quilty turns and advances.

QUILTY: Gee, I'm just dying for a drink. I'm just dying to have a drinky.

He collapses into a draped chair in the neighboring room, picks up a glass from next a full ashtray and drinks from it.

HUMBERT: You're dying anyway, Quilty.

Humbert sits opposite him, left 3/4 profile to the camera, switching the gun from his right hand to his left.

QUILTY (spitting out the drink): Geez, why do my friends always put their smokies out in the drink?

31 MCU Humbert, the chambers of the gun loaded. (07:28)

QUILTY (off screen): So unsanitary.

HUMBERT: Quilty, I want you to concentrate. You're going to die.

32 MCU Quilty from beyond and left of Humbert, lighting a cigarette. (07:33)

HUMBERT: Try and understand what is happening to you.

QUILTY: You are either Australian, or a German refugee, and this is a gentile's house. You better run along.

HUMBERT: Think of what you did, Quilty, and think of what is happening to you, now.

QUILTY: Hey, that's a, that's a durling little gun you got there. That's a durling little thing. How much a guy like you want for a durling little gun like that.

Humbert has produced a note from his pocket and hands it to Quilty. He was likely holding the note earlier, in shot 11.

HUMBERT: Read this.

QUILTY: What's this, a deed to...

33 MCU Humbert. (08:08)

QUILTY (off screen): ...the ranch?

HUMBERT: It's your death sentence. Read it.

Shot 30 | Shot 31 |

|  |

Shot 32 | Shot 33 |

|  |

34 MS Quilty from beyond Humbert. (08:12)

QUILTY: Can't read, mister, never did none of that there book learnin, y'know.

HUMBERT: Read it, Quilty.

QUILTY: Hmmm. Do do, do do do, do do, do do do de-do. Because you took advantage of a sinner. Because you took advantage. Because you took. Because you took advantage of my disadvantage. Say, that's a dad...

35 MCU Humbert. (08:41)

QUILTY (off screen): ...blasted durn good poem you done there.

36 MS Quilty from beyond Humbert. (08:44)

QUILTY: When I stood Adam naked...oh, Adam naked, you should be ashamed of yourself, Captain, before a federal law and all its stinging stars. Tarnation, you old horn toad, that's mighty pretty. That's a pretty poem. Because you took advantage. It's gettin a bit repetitious, isn't it? Because, another one, because you cheated me. Because you took her at an age...

37 MCU Humbert. (09:13)

QUILTY (off screen): ...when young lads...

Humbert grabs the paper.

HUMBERT: That's enough.

The implication is that Humbert had expected Quilty, a playwright, to recognize Humbert's writing as brilliant and be overwhelmed by it rather than making sport of it, which makes a joke of Humbert's very core, his excuses and fabrications. Unable to tolerate this, Humbert grabs the paper back.

There are also, however, various references to the "bard" in the film and book, and though the mind springs to Shakespeare (or Poe, considering Humbert's worship of him) we should perhaps recollect Humbert's efforts.

38 MS Quilty from beyond Humbert. (09:15)

QUILTY: Say, what you take it away for, mister. That's gettin kind of smutty there.

HUMBERT: You have any last words before you die, Quilty?

Quilty tosses away the cigarette he's been smoking and assumes another voice.

QUILTY: Listen, Mac. You're drunk, and I'm a sick man.

Quilty stands.

Shot 34 | Shot 35 |

|  |

Shot 36 | Shot 37 |

|  |

Shot 38 | Shot 39 |

|  |

39 Quilty finishes standing, MS of he and Humbert before a fireplace above which is a painting of a nude woman, more bottles and several statuettes. (09:32)

QUILTY: This pistol packing farce is becoming a sort of nuisance.

He approaches an open carton behind a bust of a woman the profile of which is 3/4 to the camera from the rear. He takes a boxing glove from the box.

QUILTY: Why don't you and I sort of uh settle this like two civilized people.

He slips on the second glove.

QUILTY: ...getting together and settling something...

40 MS of Quilty from the front, the bust to his left and the ladder by the window beyond. (09:45)

QUILTY: ...instead of, uh, all right, put em up.

41 MCU of Humbert. (09:49)

HUMBERT: Do you want to die standing up or sitting down?

Shot 40 | Shot 41 |

|  |

Shot 42 | Shot 43 |

|  |

42 MS Quilty. (09:50)

QUILTY: I want to die like a champion.

Quilty makes boxing moves.

43 MCU Humbert, closing his eyes to shoot the gun. (09:52)

44 Medium shot Quilty. Humbert shoots, hitting Quilty's glove, and two bottles on a packing crate beyond shattering. (09:52)

Quilty stops and looks at a tear from the bullet in his glove.

Before continuing on, I'd like to note that we've had a set change here. When Humbert entered and passed through this room earlier, the bust of the woman and the crate with the boxing gloves wasn't there.

The donning of the boxing gloves echoes Humbert's earlier donning of his own gloves. The boxing carries us back to Kubrick's twin boxers in Day of the Fight, and the boxer in Killer's Kiss who came to the aid of his dance hall girlfriend when she was kidnapped by her boss.

The bust of the woman is believed to be perhaps of Antonia Minor in the guise of Ariadne, who gave Theseus the clew by which to navigate the labyrinth. I cover this in the post, Portrait of Lolita, an Analysis of the Shooting of the George Romney Painting.

QUILTY: Gee.

He takes his hand out of the glove to see if it's all right.

QUILTY: Right in the boxing glove. You wanta...

45 MCU Humbert, the smoke from the gun clearing. (10:00)

QUILTY (off screen): ...be more careful with that thing.

46 MS Quilty again. (10:02)

He throws down the gloves.

QUILTY: Listen, Captain, why don't you stop trifling with life and death. I'm a playwright, you know, I know all about this sort of tragedy and comedy and fantasy and everything.

Having backed toward the piano he sits down on its bench.

QUILTY: I've got 52 successful scenarios...

Shot 45 | Shot 46 |

|  |

47 MCU Humbert form slightly above. (10:18)

QUILTY (off screen): ...to my credit. Added to which...

48 LS Quilty before the piano. (10:20)

QUILTY: ...my father's a policeman. Listen, you look like a music lover to me. Why don't you let, why don't...

Quilty is here referring to the Enchanted Hunter's Hotel where he masquerades as a policeman. He turns to the piano.

QUILTY: Why don't you let me play you a little thing I wrote last week.

He begins to play Chopin.

49 MS Humbert from slightly above. He stares in confusion as Quilty plays. (10:31)

QUILTY: Nice sort of opening, maybe?

50 MLS Quilty before the piano, turning to face Humbert. (10:35)

QUILTY: We could dream up some lyrics, maybe. You and I dream them up together? You know, share the profits?

He plays a few more bars.

QUILTY: You think it'll make the hit parade?

He begins the same piece over again.

QUILTY (manic, singing): The moon was blue, and so were you, and I tonight, she's mine tonight, yours, she's yours tonight, and...

Grabbing a bottle from the piano and drinking from it, Quilty attempts to fake Humbert out, now throwing the bottle at him and leaping and fleeing from the piano.

The lyrics Quilty comes up with end up referring to Lolita, with Quilty acknowledging Humbert's sensitivity to the issue and changing it to she being Humbert's.

Shot 47 | Shot 48 |

|  |

Shot 49 | Shot 50 |

|  |

51 LS from the foot of stairs, looking over the oval pattern of the Greek key-hole design wrapping the entry floor and the ping-pong table within as Quilty flees into the circle, Humbert firing at him. (11:00)

Humbert chases, firing another shot, then another as Quilty passes the table, another, another. Quilty purposefully knocks over the statue of the woman with the high heeled shoe on her head. Humbert dances around the boxes he pushes over, giving chase. As Humbert approaches the camera he fires another shot.

52 LS Quilty toward the height of the stairs, collapses, holding his leg. (11:08)

53 MS Humbert twice fires his gun which is now empty. (11:09)

54 LS Quilty from the foot of the stairs. (11:10)

QUILTY: Shee, you hurt me, you really hurt me.

55 Humbert at the foot of the stairs between twin statues of "nymphets", each with a forearm raised to brow, mirroring one the other. It is as if they are shielding themselves from witnessing the action. Humbert reloads his gun. (11:16)

QUILTY (off screen): Listen, if you're trying to scare me you did a pretty swell job all right. My leg will be black and blue tomorrow.

56 MLS Quilty. He attempts to pull himself up the steps. (11:22)

QUILTY: You know this house...

57 LS Humbert at the foot of the stairs. (11:25)

QUILTY (off screen): ...is roomy and cool. You can see how cool...

Shot 52 | Shot 53 |

|  |

Shot 54 | Shot 55 |

|  |

Shot 56 | Shot 57 |

|  |

58 LS of Quilty from the side on the second floor. (11:27)

The portrait that was downstairs is now upstairs resting on a tiger rug.

QUILTY: ... it is. Oh. (He grimaces in pain as he pulls himself along.) I intend on moving to England or Florence forever. You can move in.

59 MS of Quilty. (11:33)

QUILTY: I've got some nice friends, you know, who can come and keep you company here. You can use them as pieces of furniture.

Quilty was, in effect, as a piece of furniture when Humbert entered, blended with the chair, hidden under the drape and emerging from it. The idea of people as pieces of furniture was not in the book. Kubrick revisits this idea of people serving as furniture in A Clockwork Orange and Eyes Wide Shut. He also does so in 2001 with the red, Djinn furniture used in the space station. Djinns, having the ability to transform, can become anything.

When Quilty says there's a guy who looks like a bookcase, this may recall Nabokov's Laughter in the Dark in which a married art critic falls in love with a seventeen-year-old girl. She is at his house one night and he later believes he spies her still there, hiding behind a bookcase, and he approaches ready to make love to her, but the scarlet that he thought was her dress is instead a pillow. They do have an affair, his marriage is ruined, she ends up using and abusing him, in the end he decides to kill her, but she she takes the gun and kills him instead.

60 LS Humbert down the steps, reloading his gun as he ascends. (11:39)

QUILTY (off screen): This one guy looks just like a bookcase.

61 LS Quilty. (11:43)

QUILTY: I could fix for you to attend executions. How would you like that? Just you there, nobody else, just watching. Watch. You like watching, Captain. No, 'cause not many people know that haha, ow, ow, that the chair is painted yellow.

He pulls himself behind the portrait which was formerly downstairs.

QUILTY: You'd be the only guy...

62 MS Humbert ascending to the top of the steps. (12:05)

QUILTY (off screen): ...in the know. Imagine your friends, you could tell them.

Shot 59 | Shot 60 |

|  |

Shot 61 | Shot 62 |

|  |

63 MS of the portrait of the woman on the tiger rug, two other paintings leaning against it, Quilty now entirely hidden behind except for his feet. (12:08)

Humbert shoots and a bullet pierces the woman's dress.

QUILTY: Oh, that hurt!

Another bullet goes through the woman's wrist.

A bullet through her elbow (as Quilty grabs the frame from behind, exclaiming in pain).

One through her upper arm as the camera zooms in on her face.

One through her chest.

One through her cheek.

We hear Quilty collapse behind.

Fade to black at 12:16.

Note how, with Quilty behind the painting, grasping its frame, he has the appearance of being seen through and behind the painting, doubling the figure of the woman with what appears to be (but is not) his neck and the neck of his clothing. It's a great effect.

Up to the shooting of the portrait of the woman, the scene is one of disconcerting mania, Quilty's behavior seemingly bizarre and in conflict with the situation, and especially discombubulating to the viewer with their moving directly into this from the placidity of the opening credits with the soft focus painting of toenails. Quilty shifts his voice from one character portrayal to another, which is his role in the film, taking on various camouflage personas, ever the trickster and thorn in Humbert's side. The two things we concretely know about him, apart from Lolita's later troubling description, is that he is a writer and, like Humbert, sexually attracted to "nymphets". As the writer of The Nymphet, he functions as a kind of shadow for Humbert as the author of Lolita (as opposed to Nabokov). What makes him most peculiar is that, acting as Humbert's more self-aware shadow (for Humbert ever lies to himself and us as he abuses Lolita), Quilty continually threatens Humbert with his knowledge of his actions, while seemingly unconflicted as to his own predilections.

Nabokov had much of this scene--which is dark as dark can be--in his book but eviscerated it in the screenplay, which begins with the murder of Quilty. Humbert driving up to a wooden manor, the camera glides down one of its ornate turrets where it finds Quilty asleep in bed with his drug paraphernalia beside him. Humbert enters the mansion that is supposed to be as out of a "medieval fairy tale". He meets Quilty on the stairs. No words pass between them. He pursues and shoots. Plain and simple.

Now begins a silent shadowy sequence which should not last more than one minute. As Humbert levels his weapon, Quilty retreats and majestically walks upstairs. Humbert fires. Once more. We see him missing: the impact of a bullet sets a rocking chair performing on the landing. Then he hits a picture (photograph of Duk-Duk ranch which Lolita visited.) Next a large ugly vase is starred and smashed. Finally, on his fourth fire, he stops a grandfather clock in its clacking stride. The fifth bullet wounds Quilty, and the last one fells him on the upper landing.

Not quite the Lolita we know. Can you imagine Kubrick's film opening with instead a bullet smashing of the face of the grandfather clock? Kubrick moved the grandfather clock to the Haze residence and left it unscathed.

The screenplay moves on to Humbert's psychiatrist speaking about his case and Humbert's autobiography and we are instructed how to feel about it.

I have no intention to glorify Humbert. He is horrible, he is abject. He is a shining example of moral leprosy. But there are in his story depths of passion and suffering, patterns of tenderness and distress, that cannot be dismissed by his judges...here lurks a general lesson: the wayward child, the egotistic mother, the panting maniac...they warn us of dangerous trends. They point out potent evils. They should make all us of--parents, social workers, educators--apply ourselves with still greater vigilance and vision to the task of bringing up a better generation in a safer world.

Though pedophilia is a serious and terrible concern, this intro begins to sound like one of those early exploitation/educational films on marijuana.

The introduction done, Nabokov then begins the story proper. We've a number of scenes in which Humbert's youth is given an account, his passion for Annabel at fourteen (who died), his failed marriage, his torments, all annotated with narrative from the psychiatrist. Finally we arrive at a scene in which Humbert, an aficionado of Edgar Allen Poe (as was Nabokov), lecturing on him, loses it while looking for a poem that he insists begins with "n...y...m. N as in Annabel." He wishes to illustrate the nymphet, and begins to describe such and their capacity to bewitch.

Between the age limits of nine and fourteen there are certain maidens: they bewitch the traveler who is twice their age and reveal to him their true nature, which is not human but nymphic--in other words, demoniac...I am speaking of a certain fey grace, of the elusive, shifty, soul-shattering, insidious charm that separates the preteen demon from the ordinary...Oh, how horrible full-grown women are to the nymphet-lover! Don't come near me! Hands off!

He faints. He goes into a hospital for some relaxation. Afterwards he goes to Ramsdale hoping for relaxation there as well, but instead meets Lolita.

It may be that the book's version of Quilty's murder is much like the film's, but there are also significant differences.

In the book, quite drunk, Humbert wanders Quilty's house looking for him. When Quilty emerges, he pays no notice to Humbert, acting as a sleepwalker. When he does take notice of Humbert, in the "Oriental parlor", he asks if he's Brewster. Humbert replies that he is and suggests a chat before they start, to which Quilty observes he doesn't look like Jack Brewster. We have the conversation about people using the telephone and entering the house without knocking (in the film, Quilty saying Lolita may have used the phone).

Humbert demands as to whether Quilty remembers Lolita and Quilty acts or seems unsure. But when Humbert states she was his daughter, Quilty denies him fatherhood, insisting he was not. Looking for a smoke and a drink, Quilty realizes Humbert has a gun and begins his talk imitative of movie characters. Humbert demands he concentrate and Quilty eats a cigarette, not having a match. After telling Humbert to run along, that Humbert is either an Australian or German refugee and this is a gentile's house (an odd bit of dialogue that Kubrick retains, Australian being a joke as to Austrian being often confused with Australian), he warns Humbert he has a gun, a Stern-Luger, in the music room. Humbert fires at a spot near his foot. Quilty warns he should be more careful (just as Humbert will later warn Charlotte when she pulls out the gun).

Quilty's manner disorienting Humbert, Humbert attempts to make Quilty understand why he's about to die. He accuses him of kidnapping Lolita, and Quilty now rallies. He protests he'd saved her from a beastly pervert, he was not responsible for the rapes of others, and "you got her back, didn't you?" He confesses he's practically impotent and "had no fun with" Lolita. After a wrestling match over the gun, Humbert has Quilty read his poem.

Quilty attempts to convince Humbert to let him live, offering him his home. He offers him the use of exotic friends of his, such as a young lady with three breasts he could use as a house pet.

...Brewster, you will be happy here, with a magnificent cellar, and all the royalties from my next play--I have not much at the bank right now but I propose to borrow--you know, as the Bard said, with that cold in his head, to borrow and to borrow and to borrow. There are other advantages. We have here a most reliable and bribable charwoman, a Mrs. Vibrissa--curious name--who comes from the village twice a week, alas not today, she has daughters, granddaughters, a thing or two I know about the chief of police makes him my slave.

Nabokov, via Quilty, points out how peculiar is Vibrissa's name. It seems Nabokov may be pointing this out for a reason but I've not been able to make any kind of relevant associations. Vibrissae are whiskers.

Again, in the book, even though he knows who he is, Quilty calls Humbert Brewster.

Not even the promise of Quilty's arranging for him to attend executions halts Humbert who shoots again. Now, Clare the unpredictable bangs out a tune on the piano, while attempting to open a seaman's chest near it with his foot, ostensibly making for that Stern-Luger. Humbert's next shot hits him in the side. They bound through the hall. Quilty ascends the staircase, Humbert shooting him repeatedly.

...he slowed down, rolled his eyes half closing them and made a feminine "ah!" and he shivered every time a bullet hit him as if I were tickling him...

And so it goes, Quilty fleeing Humbert's bullets which keep finding him. Quilty retires to his bedroom and Humbert shoots him to a bloody pulp in his bed.

I may have lost contact with reality for a second or two...a kind of momentary shift occurred as if I were in the connubial bedroom, and Charlotte were sick in bed. Quilty was a very sick man. I held one of his slippers instead of the pistol--I was sitting on the pistol.

He sits and waits for Quilty to die.

Quilty does not unfold himself out from under a sheet, disassociating himself from a piece of furniture. There is no ping-pong game. There are no boxing gloves. Quilty does not pound out Chopin on the piano. Quilty does not needle Humbert with the accusation that he likes "to watch". Humbert does not shoot Quilty through a painting of a young woman.

Having searched periodically for it, I finally found the match of the portait in the movie, it having occurred to me to search through Gainsborough's rivals. The portrait turns out to be by George Romney, and of Frances Puleston (Mrs. Bryan Cooke). The image below is from the Metropolitan Museum of Art online, with a little color adjustment on my part. Frances lived from 1765 to 1818 and ten sittings were held for the portrait between 1787 and 1789.

Two of the bills Lady Lyndon signs in Barry Lyndon are dated 1789. Actually, the first looks like it's perhaps 1787, but the bill was for a charge from 1788 so it would have to be 1789.

Frances was a promotor of the Society for the Education of the Poor in the neighborhood of Doncaster (Yorkshire).

Col. Bryan Cooke, of Owston, Yorkshire, was a member of the Parliament for Malton. His first marriage was to Frances, with 4 children. His 2nd marriage was to Charlotte Bulstrode Cooke, daughter of Sir George Cooke.

Later in the analysis I discuss the line in Nabokov's book that states that though Humbert was able to have intercourse with Eve, his longing was for Lilith, who in legend was his first wife, so it may be significant, as to the choice of this painting, that Bryan Cooke was married first to Frances and then to Charlotte, Charlotte being Lolita's mother's name.

George Romney, the painter, separated early from his wife. After 20 years he became enamoured of a young woman named Amy Lyon. At the age of 15 she had become the mistress of Sir Henry Harry Featherstonhaugh, dancing nude at his stag parties. They had a child at 16. Then, thrown over by Harry, she became the mistress of Charles Francis Greville, and it was during this time that she met Romney, I guess about 1781 when she was 17. Romney was in love with her, she rejected him, so their relationship seems to be his paintings of her, she becoming the most painted woman in Europe. Greville, determining he needed to move his attention to marrying a rich woman, sent Emma on vacation to live with his uncle, Sir William Hamilton, in Italy. Emma went, thinking it was only a short separation, having no idea Greville had arranged with Hamilton she would be his mistress. Eventually, she and Hamilton married. While still married to Hamilton, who was far older than her, she later had a love affair with Horatio Nelson, for which they were both famous.

By coincidence or not, with Cooke's second wife, Charlotte, and the painter's muse, Ann Lyon, we have vaguely associated with the portrait the character of Charlotte, Lolita's mother, and the actress Sue Lyon who played the part of Lolita.

The manner in which the shadow of a column falls on the painting in the movie hides a curious effect of the portrait so that it carries within a resemblance to an eye with Frances' head at the center.

I'm a little reminded of Magritte's blue sky/eye painting, "The False Mirror".

Sold to the MMoA in 1943, the exhibition history of the painting is a limited one. The Met gives:

London. Royal Academy of Arts. "Winter Exhibition," January 6–March 14, 1896, no. 35 (lent by Philip B. Davies-Cooke).

New York. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. "The Bache Collection," June 16–September 30, 1943, no. 61.

Indianapolis. Herron Museum of Art. "The Romantic Era: Birth and Flowering 1750–1850," February 21–April 11, 1965, no. 13.

New York. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. "The Eighteenth-Century Woman," December 12, 1981–September 5, 1982, unnumbered cat. (p. 53).

That this was painted by George Romney takes us back to The Killing with its scene of George's bullet-ridden face. Another connection there. (See a couple of sections below for the relevant image and discussion on that.)

A post dedicated to Portrait of "Lolita", an Analysis of the Shooting of the George Romney Painting" is here. I elaborate further on the portrait in the second section.

UPDATE NOVEMBER 2020: John Cork, who knows all things James Bond (an interesting subject), sends along some humorous information on the painting that he picked up along the way. And it seems the painting that Kubrick originally had in mind ended up not being the portrait that was used. But let's let him tell the story:

I produced and directed a series of documentaries on the James Bond films for their DVD and subsequent Blu-ray releases. During that time I was able to interview Syd Cain, the Associate Art Director for Lolita. Syd told me the story of the painting in the film.

Kubrick goes to Syd and tells him he wants a particular painting for the scene that is to be shot at Elstree Studios in the decrepit house set. Cain goes off and finds the painting Kubrick named, and lo and behold, he gets it on loan from the museum! He brings it back, places it in the set, and goes back to work. Art Directors like Syd are always working on the next set while the crew shoots with the current set. other members of the art department, most notably the set dressers, work with the crew on the day of shooting for the most part.

Well, Syd decides to go and see how things are working on the Quilty House set, and he sees his set dresser (I believe) spraying down the walls to make them look dirty. This is usually done with a washable product like “Streaks and Tips” in the US, but this guy was just about to spray OVER the painting. Syd screamed. The guy stopped. Syd informed him that this was the original painting, irreplaceable. The set dresser apologizes profusely. About then the special effects man walked up and said, “You think that’s bad, I just placed two bullet charges on the backside of the canvas!”

So, Syd had to go to Kubrick and tell him that no, he could not blow a hole in the painting he wanted to use. Since they were already shooting some of the scene, there was no time to create a reproduction. Cain convinced him to use another painting, a reproduction that was already on the set…the Romney painting that was from the Elstree Studios prop warehouse. This is why you see it by the door in one shot, then later atop the stairs. It was always meant to be by the door. It was only because Syd Cain had obtained the original of the painting Kubrick wanted that the Romney painting ended up being the painting being shot in the final film. I wish I could tell you what the intended painting was, but that information is lost to my memory.

What is certain is that Kubrick didn’t get the painting he wanted. No one knew the strange connection between Romney’s muse and the surname of the lead actress or the artist’s first name and the character in The Killing. But it is just these kinds of connections that so often arise in great art, little webs of unintended connections that draw us into larger understandings of themes and help us find greater meanings.

Cork was diligent also about wanting to check Cain's own words on the subject, pursued Cain's autobiography, and added this:

Syd Cain relates a different version of this story in his autobiography, “Not Forgetting James Bond.” In that version, Sellars is hiding behind an original Constable when Syd Cain realizes that the painting is going to be harmed and he then steps in. He recalls his set dresser obtaining a number of original paintings by Constable and Hogarth for the set. He also recalls painting a reproduction of the Constable after saving the painting, but whatever the fate of that effort may have been, it is the reproduction of the George Romney painting from the Elstree prop department that was used in the final version of the film.

It's a great story, and I thank Cork for sending it along.

The location is Hilfield Castle, Hilfield Lane, Bushey, Hertfordshire, England. The interior movie set has nothing at all to do with the interior of Hilfield.

The castle was designed for George Villiers, brother of the earl of Clarendon, which suits it being the home of Clare Quilty.

After the killing of Quilty, the book follows Humbert's limpid, dreamy drive that results in an easy capture by the authorities, and then ends after a few pages of reflections. The screenplay instead begins with the murder rather than ending with it. Kubrick had told Nabokov the murder scene should begin the film as in the book people likely stuck around until Humbert bedded Lolita then began to lose interest, which would probably happen as well with the movie, so he reasoned that the murder of Quilty should begin the film so that the viewer would stick with the movie to the end to find out what happens.

That's well and good and cinematic but Kubrick is cyclical in his films and so will this one be, Lolita opening and ending with Humbert at Quilty's mansion. Fear and Desire opened with the same mountain scene that it ended upon. Killer's Kiss opened with the boxer waiting in the train station for his girlfriend, we had the flash back story, and then the movie ended with the train station again in which the boxer waits for his girlfriend. 2001 opened and closed with Thus Spake Zarathustra and a cosmic view of Earth (referring to Nietzsche's "the eternal return", see the opening section of part one of my analysis on 2001 for more on this). Kubrick has many more cycles in his films but these are very straightforward examples.

Fear and Desire Opening | Fear and Desire Closing |

|  |

Shot 2 from Lolita | Shot 538 from Lolita |

|  |

Nabokov does not have the cycle in the screenplay, the end repeating the beginning, nor does he have it in the book.

The shooting of the woman in the screen right cheek might remind of George's shooting in The Killing.

George's desperate need to be viewed as successful by his wife, Sherry, who abhors him, is what gets him in this holy mess in The Killing. He tells her about his involvement in a race track heist that will soon happen. She tells her boyfriend, who is only sexually interested in her until he learns of the race track heist and then is only interested in the money. After the heist is successfully pulled off, Val, the boyfriend, attempts to rob the race track heist conspirators of their loot. George shoots at Val. Val shoots George. Wildly shooting back, George kills Val as well as somehow accidentally managing to slaughter all else in the room, his fellow conspirators who were waiting with him for the loot to arrive (I've never quite managed to figure out how he unintentionally slaughters them all plus the boyfriend and his helper). He runs home to Sherry to find her packing. She tells him he's a loser and to get lost. He shoots her and they both die.

The man shot in the face becomes the portrait of the woman shot here. I elaborate in Portrait of "Lolita", an Analysis of the Shooting of the George Romney Painting how this relates to Humbert, how he is not only shooting Lolita, by proxy, but also himself, but will look at some other relationships here.

Earlier, in the living room of Quilty's castle, a bust of Shakespeare on a pedestal is replaced with one of Ariadne when Quilty pulls boxing gloves out of a crate which had not been initially there. A male figure replaced with a female. Another change has also taken place, the carton holding the boxing gloves is stencilled GOELENS rather than, as are the other crates, BOELENS. I don't know if the two changes relate to one another or not.

What one immediately comprehends is that the painting, behind which Quilty crawls, likely has very much to do with Lolita, which is no big stretch. In the Nabokov screenplay, Nabokov does at one point have Lolita and Humbert watching Quilty's, The Nymphet on TV. When Humbert argues it's trash, Lolita disagrees, saying it's quite exciting and that "he finds the girl and shoots her."

One has the sense that Quilty and the painting act as a proxy for Lolita, and that the shooting also represents Humbert's traumatizing of Lolita throughout her young life.

But to look more closely at the replacement of the bust of Shakespeare with Ariadne...

Let's step back to the statue of the Roman (or Spartan) warrior with the woman clasped to him. This stands opposite the statue of the woman with the shoe on her head (shot 4) and once we realize this we can see how the shoe echoes, as a headdress, the Roman helmet with the crest.

Below is a version of the Spartan statue on eBay that is slightly different from the one in the movie (I can find no attribution anywhere for the original). We see with the statue on eBay that a sheet is wrapped about the woman's legs. With the statue in Lolita, the sheet around the woman looks instead to be a serpent twined about her legs, or perhaps her legs are themselves the serpent. The spear seems to be held a little differently. The helmet seems also to be fashioned a little differently, we don't see the curls of the hair as we do in the version on eBay, and I don't think it's because those curls are obscured by what kind of looks like a transparent scuba diving mask worn by the statue at Quilty's. At present I can find no other statue resembling either of these two, but both Isobel Lilian Gloag, and John William Waterhouse painted versions of Lamia as enchantresses kissing warriors. Gloag's Lamia has a serpent tail while Waterhouse's Lamia is wrapped in the body of a serpent. At least Gloag's version is based on the John Keats' poem Lamia. Wikipedia relates that in the poem, Hermes, hearing of a nymph who is the most beautiful in the world, comes across Lamia. The serpent reveals to him the nymph, who was invisible, and he restores Lamia to human form. Lamia goes to find Lycius, a Corinthian youth she had seen during one of her spirit voyages as a serpent. At their wedding feast, Apollonius reveals Lamia's true identity. Lamia disappears and Lycius dies of grief.

Lycius is also a surname of Apollo. Knowing this, we can look to the myth of Apollo and Python and Daphne. Having killed Python, Apollo is shot with a poisoned arrow of love by Cupid, whereupon he immediately falls in love with Daphne, who Cupid shoots with a poison arrow of hatred for Apollo. Fleeing from him, she is turned into a laurel tree. By the use of the laurel in his lyre, Apollo will always have her with him.

This is why we have the harp located near the statue of the soldier (Apollo) and the being that could be either Python or Daphne, and probably represents both. I have already written of Apollo's relationship to Python and Daphne at some length in my analysis of Picnic at Hanging Rock. In brief, Python is actually a part of Apollo-Python, and Daphne, modeled upon Artemis/Diana, is a twin of Apollo's. There is a story of continual attraction and repulsion. In python's coils we can find the spirals of eternal recurrence.

The woman with the shoe-crest seems to answer this statue, as if she has become male and female merged as one--and this is a theme in Lolita, the androgyne. The shoe rather more resembles a Phrygian cap on her, which is only a convenient opportunity for me to mention the Phrygian cap, and it is worthy of mention for two reasons. With the French Revolution, it came to represent freedom, which ties in with Quilty asking if Humbert has come to free the slaves. Also, Priap is referred to in the novel Lolita, and the cap identified inhabitants of Troy and was also the head covering worn by Priapus, a Greek Garden god. If we are to believe that Nabokov suggested to Kubrick that Lolita be played by a dwarf (so I have read), and even if not, it should be noted that Priapus is often depicted as a dwarfish man with a large phallus, very like the small statues of Hermes that guarded Greek entrances. Priap is mentioned several times in the novel and twice in the screenplay. In the novel, Humbert speaks of Lolita as being dreamed up by Priap, and also recognizes Priap (in others) by virtue of Lolita. In the case below it is a man perceived as a satyr (sometimes equivalent to a priap) standing under a tree filled with dappled Priaps (the leaves).

"...it dawned upon me what I recognized him by was the reflection of my daughter's countenance--the same beatitude and grimace but made hideous by his maleness."

In this particular instance in the novel, the person Humbert at first perceives as Priap (who had been watching Lolita play tennis) then suddenly morphs into "Detective Trapp", who Humbert is convinced is the shadow tailing them--but who is actually shadowing Humbert and Lolita is, of course, Quilty. There is a confluence of tennis, Trapp, Roman noses and Champion at one point, all on the same page, all of which we find in Quilty's ramblings during the ping pong match. So that ping pong match is based on the tennis game in which Humbert perceives a Priap watching her play, who morphs into Detective Trapp but is instead Quilty. Another time, Humbert realizes all his Trapps (to be taken literally as traps) are the same person in that they are all constructs of his paranoia.

A man named Swine is the desk clerk at the Enchanted Hunters Hotel where Humbert and Lolita will stay. Algernon Charles Swinburne wrote a poem on "Dolores (Notre-Dame des Sept Douleurs)" and identified Dolores in it as a daughter of Death and Priapus. Certainly Nabokov knew about this. Dolores is Lolita's birth name.

I have a good bit more on this statue of the woman clinging to the man in section three, under Humbert Was Perfectly Capable of Intercourse with Eve, But It Was Lilith He Longed For.

The bust of Shakespeare, which is replaced with the female bust of Ariadne, when Quilty pulls out the boxing gloves, is another example of this replacing of the male with the female, or a kind of merger, as is had with the female statue with the shoe hat answering to the Roman warrior with the woman, or Apollo with Python/Daphne, who are parts of himself. Why Shakespeare? Maybe it's simply a kind of pun referring back to the Roman warrior with his spear stabbed through the sandwich. Shakespeare, some say, means a spearman in the idea of someone brandishing (shaking) a spear. Nabokov makes much use of puns. Why not Kubrick? Why analyse these things in Nabokov and not suppose they might be present in Kubrick's films as well? Plus, in the book, Quilty had spoken of the "bard".

And, of course, we have the replacement or merger of masculine and feminine with the portrait of the woman that Kubrick has plainly moved from the bottom floor to the second floor just so Quilty can crawl behind it and Humbert can shoot them both at the same time, this portrait of the girl or woman and Quilty, who uses the portrait of the girl/woman as his shield.

That portrait is placed upon the skin of a roaring but vanquished tiger, who must be none other than Charlotte, Lolita's mother, as we shall see. A cat woman, often dressing in leopard print clothing, she at least partly corresponds to the cat woman in A Clockwork Orange who is murdered by the Priapus Alex becomes when he takes up the statue of the phallus and assaults her with it.

The smile of the woman in the painting becomes nearly as enigmatic as the Mona Lisa's, a painting which some believe is based on Da Vinci's lover, Salai, who entered his household at the age of ten as an apprentice and remained with him until his death. By magically moving the portrait from the first to second floor, Kubrick makes her a mystery and demands she be examined and not ignored. Like Humbert's taking of Charlotte's queen, in the chess game, with a knight that can leap around corners, the portrait has translated itself around the corner and up the staircase, insistent upon our recognition of it.

Is it fair to assign to the girl, Lolita, a profusion of poetic symbolism that abstracts her situation so the brutality of her sexual imprisonment by Humbert is glossed and subverted by so many words and archetypes? Does it actually work as Nabokov used it, as a foil for Humbert, an attempt by him to subvert his treachery and abuse? How does this work and does it work when transferred to Kubrick's celluloid portrait? Do we lose Lolita along the way or do we awaken to civilization's repeated attempts to diminish horror with a pretty, noble face that runs counter the reality of a situation? It's something to be considered.

One may be aware that is thought by some that Shakespeare's works were written by another, probably a member of the nobility, for whom Shakespeare served as a front. This would be another reason to substitute Shakespeare's bust with that another, which would have us reflect upon a number things concerning the film and novel.

There is a town called Quilty in the county of Clare in Ireland. I've been unable to deduce anything meaningful in that regard, but one wonders if there is a connection with Quilty's full name being Clare Quilty.

Quilty's name is a play on the word guilty. There's also a kind of reversal in it with quilty becoming guilty, the right-curling tail of the q turning and becoming the tail of the left-curling g. But there is more to the name. As we will later see in the film, Quilty also refers to the quill, as in the feather/plume used for a pen, which fits with Quilty being a writer.

In the book, Vivian Darkbloom appears to only once make a physical appearance, and that one is quickly brushed over without identifying her specifically, instead one later realizes who the woman described was, but she is a character who should be in bold type, for which reason Kubrick has given her more scenes in the film. In the book, Vivian is credited as co-authoring with Quilty The Lady Who Loved Lightning. She is also stated as having authored My Cue, a biography on Quilty. Nabokov has one of Lolita's classmates named Vivian McFate, then later, while Humbert and Lolita are traveling, we have this following passage in which "fate" is again linked with Vivian.

"You've again hurt my wrist, you brute," said Lolita in a small voice as she slipped into her car seat.

"I am dreadfully sorry, my darling, my own ultraviolet darling," I said, unsuccessfully trying to catch her elbow, and I added, to change the conversation--to change the direction of fate, oh, God, Oh God: "Vivian is quite a woman. I am sure we saw her yesterday in that restaurant, in Soda pop."

"Sometimes," said Lo, "you are quite revoltingly dumb. First, Vivian is the male author, the gal author is Clare; and second, she is forty, married and has Negro blood."

"I thought," I said kidding her, "Quilty was an ancient flame of yours, in the days when you loved me, in sweet old Ramsdale."

That is the only time Vivian is mentioned by Humbert, at least by name, to Lolita.

Here's what Nabokov wrote of their meal in Soda.

We spent a grim night in a very foul cabin, under a sonorous amplitude of rain, and with a kind of prehistorically loud thunder incessantly rolling above us.

"I am not a lady and do not like lightning," said Lo, whose dread of electric storms gave me some pathetic solace.

We had breakfast in the township of Soda, pop. 1001.

This occurs when they are being followed by Quilty, their blue car "shadowed" by his red car, the driver described as one who "with his stuffed shoulders and Trappish mustache, looked like a display dummy, and his convertible seemed to move only because an invisible rope of silent silk connected it with our shabby vehicle."

Again, the Trapp, Quilty mistaken as the detective, who is more than slightly unreal.

As you can see, Lolita stating she is not a lady and doesn't like lightning, has referred to The Lady Who Loved Lightning, co-authored by Vivian and Quilty. Later, when Humbert says he believes he saw Vivian in Soda, Lolita rejoins that Vivian is instead male and that Clare (Quilty) is the female. We have with this another example of the male and female swapage. But if we dig down into it, Vivian is male, as Vivian Darkbloom is actually Nabokov's alter, for Vivian Darkbloom is an anagram of Vladamir Nabokov. So Vivian is both male and female. Nabokov said he created her when he was thinking of publishing Lolita under a pseudonym, keeping his name present in the book. In the screenplay he even has Quilty remark that her name is an anagram, having hoped to bring this to the attention of the audience.

One reason why I earlier wrote of the Roman warrior with his spear and crested helmet, to whom the woman clings, being transformed/or answered by the female statue with the shoe on her head--thinking of it as the Phrygian cap worn by Priapus (and Paris)--is because of the etymology of Cue.

Cue is, yes a stage direction, which is appropriate for Quilty being a playwright, and is an abbreviation it seems of quando, "when". I read Shakespeare had it both as "Q" and "cue". Then there is the "cue" which is the billiard stick, said to be a variant of queue. The Online Etymology Dictionary states:

late 15c., "band attached to a letter with seals dangling on the free end," from French queue "a tail," from Old French cue, coe "tail" (12c., also "penis"), from Latin coda (dialectal variant or alternative form of cauda) "tail," of unknown origin.

It seems plausible that Vivian would be writing a book on Cue with Nabokov making a play on its etymological origin in the penis, as Vivian is Vladamir Nabokov's anagram. She is female-male. It would be just like Nabokov to have Cue referring back to the old cue as a penis.

Kubrick may further allude to Quilty with the feathers (as in a quill's relationship to a feather) adorning the hat of the woman in the painting. Later in the film Kubrick does have Lolita picking up a white feather and handling it as one would a pen.

All of this is more important than it seems, for we will find Kubrick often toying with the role of the author in their works, their presence in their work and their responsibility for their creations. He would do this later with Burgess in A Clockwork Orange and, to some extent, King in The Shining. In the stories that Kubrick has chosen to frame (and how he frames them) his references to the original author sometimes hinge on the Oedipus myth of the child fated to murder his father and marry his mother, free will confronting fate and finding itself without any real self-initiative to control destiny. The characters created by the author struggle against the same conclusion while the authors deny their responsibility.

Whenever I refer to the Oedipal myth I never speak of it in the absurd Freudian sense. The Oedipal myth is a mystery of fate versus free will.

What is fate and what is free will? Kubrick presents to us that question over and over again, referring not only to real life, to every person's situation, but he also refers to these fictions, importing the author as the god of their creations, and examining their responsibility, the author's role as the hidden machine, akin to the unknowable that either is the machine or is behind the machine that drives all. Though it is impossible to approach any fiction as being "real life", this is something an audience tends often to do, they describe characters of a book, a movie etc. as being real life, as if working through real life motivations, and attempt to divine the psychology of the character when instead they are looking at a construct of the author. The author may be able to realistically represent real life in a fine and clear way that sensitizes the audience to it, but it remains representation. To my eye, Kubrick sometimes examines the author as the concealed tyrant, even confronting where they have abandoned some truth in their work and taken an easy, even hypocritical way out. For instance, King began his The Shining strong, looking at the psychology that drives abuse, and the complications of alcoholism, then abandoned all of this for action driven by hidden spirits and Jack bearing almost no responsibility for his actions. Burgess did the same with his Alex, ending with the idea that all males are by rule of nature destined to be god-awful rapists and murderous juvenile delinquents, and that they grow out of this into responsible, conservative citizens--never mind it being the elders, those with power and money, who drive the destruction of the world, because Burgess was, after all, a conservative, royalist ass.

In matters of mechanistic fate or free will, I have felt that in A Clockwork Orange and The Shining Kubrick has sometimes suggested the characters as slaves of Burgess and King, their respective authors. (Perhaps slaves of his as well.) I have also wondered this with Lolita--and it's not such a ridiculous question to contemplate as one might believe. In an interview in which Nabokov was asked if his characters ever did things he didn't expect them to, he replied certainly not, "My characters are galley slaves."

As I have shown above, Quilty's mansion with its draped furnishings may remind of the end scene of The Shining, the camera's eye gliding through the lobby of the Overlook, its seating now draped with white sheets. Quilty has mentioned the possibility of his moving and so we imagine the house is closing down. However, in the book, we haven't these draperies and crates. After Humbert kills Quilty, he goes downstairs to find Quilty's friends arriving, drinking his liquor, lounging about on divans, waiting for him as they are to go to some game.

In The Shining, the big reveal is Jack, or his doppelgänger, in the photo of a party dated July 4th, 1921. What is occurring in Lolita at Quilty's mansion isn't on July 4th, but Lolita's escape from Humbert at the hospital, when she fled with Quilty, had occurred on July 4th. In the book, Humbert made a scene at the hospital, finding her having been checked out by "Uncle Gustave", but then realized police presence and reined it in. He signed a "symbolic" receipt, and left rather than making a false move that would end in his imprisonment. Thus, he was still a free man, "free to trace the fugitive, free to destroy my brother". Not only was Lolita freed from Humbert (an Independence Day of sorts), but Humbert, too, was free. For the time being.

Again, independence is brought up in the film with Quilty immediately asking Humbert if he is there to free the slaves, Quilty having identified himself as Spartacus. In the book, Lolita states Quilty's friends are his slaves. Humbert, after killing Quilty, goes downstairs and tells the friends collecting there that he has killed Quilty, and the response is not only that somebody ought to have done it long before, but that perhaps they each should do so one day.

Kubrick has slaves only mentioned once in the film, in this section, as Quilty separates himself from the chair, arranging the drape to be as a toga, but I think there's little doubt that the end scene of The Shining refers back to this scene with its drapery and the idea of independence, freeing the slaves, July 4th.

The statue with the shoe on its head stands within the maze of the Greek Key design, and is knocked over by Quilty as he attempts to make his escape from Humbert. Outside this arena, the bust of Ariadne looks on. If we reflect on the significance of the Minotaur and its maze, and its presence in Kubrick's films from Killer's Kiss on (a Minotaur production), there's added an important layer to our comprehending Quilty's transformations, different aspects yet all the same person. Again, we have the maze that makes a regular appearance in Kubrick's films (the Troy maze, I believe, is referred to in Eyes Wide Shut, and then, of course there is the famous maze in The Shining) in which a thing is repeated many times but with variations. The matter of a perceived pattern through which one attempts to divine message and meaning is one way of looking at it.

The book, Lolita, ends with a not too oblique reference to the bull/minotaur so it is a thread worth pondering.

That I’d been directly immersed into the chaos of someone’s revealed dream is how I felt the first time I watched Humbert Humbert (James Mason) enter the black-and-white baroque/rococo, bric-a-brac, moving-day set of Quilty’s mansion, through which Humbert stumbles in dumb, amazed horror, hell as a puzzle where all the pieces have been retained but splintered so fine that to find a proper order is beyond the mind’s ability to comprehend what was once object or shadow play. What manner of disorder is this? Where have all the partyers gone, for there must have been a number of them. And the white sheets draped over the furniture wonder how long since they left, and when will they be called out of storage to play again in another Kubrick film? A brittle and stagnant energy of old offered up as novel, each time with a different twist of perception, so that when the layers archaeologically pancake together in the sediment of time there’s no distinguishing between them. Harp and harpsichord tinklings hint at heaven subverted with the orgies of rebellious angels.