STANLEY KUBRICK'S BARRY LYNDON

Shot-by-Shot Analysis

Part Four

Go to TOC for this film ( (which has also a statement on purpose and manner of analysis and a disclaimer as to caveat emptor and my knowing anything authoritatively, which I do not, but I do try to not know earnestly, with some discretion, and considerable thought).

TOC and Supplemental Posts | Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Films Home

LINKS TO SECTIONS OF THE ANALYSIS ON THIS PAGE:

Lord Ludd, Shots 426 through 458

Notes on Lord Ludd. Book versus film. Location.

Subtle Flips and Dualities

Ludd

The Barber of Seville and Harlequin

Enter Lady Lyndon, Shots 459 through 493

Notes on Enter Lady Lyndon. Book versus film. Who is this guy

Reclaiming, Deja Vu, and The Shining

The Love Triangle of Pierrot, Columbine and Harlequin

The Kiss

Doubling

Callisto and Arcadia

The Red Sail

Locations and Statues

426 LS of a castle at night. Again Il Barbiere di Siviglia which played during the scene with the Prince. (1:27:48)

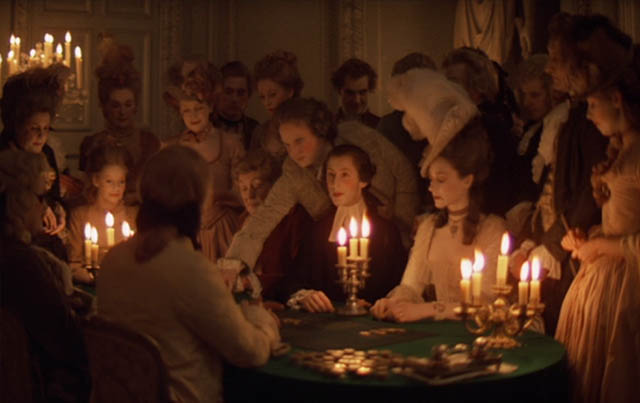

427 LS of gaming table. (1:27:54)

NARRATION:And by these wonderful circumstances, Barry was once more free again, and began his professional work...

428 From behind and to the left of Barry, Lord Ludd playing cards. (1:28:03)

NARRATION: ...as a gamester, resolving, thenceforward and forever, to live the life of a gentleman.

At this, everyone "Ah's" appreciatively as the Lord wins.

429 MS Barry and the Chevalier. (1:28:11)

CHEVALIER: Four wins.

Sung part of the aria begins.

NARRATION: Soon there was no court in Europe where he and the Chevalier were not received...

430 Return to shot 428. (1:28:22)

NARRATION: ...and they were speedily in the very best society where play was patronized and professors of that science always welcome.

431 Return to shot 429 of Barry and the Chevalier. (1:28:30)

LUDD (off screen): Pourquoi pas?

432 CU Ludd and two women. (1:28:35)

LUDD: Tout, tout, oui.

CHEVALIER: Rien ne va plus.

433 Return to shot 431 of Barry and the Chevalier. (1:28:44)

CHEVALIER (turning over a card): Numero sept.

434 Ludd and the two women dismayed. (1:28:49)

CHEVALIER: Perdant.

435 Return to Barry and the Chevalier. (1:28:55)

CHEVALIER: Faites vos jeaux.

436 Ludd. (1:29:00)

LUDD: Chevalier, will you give me credit for 5000 louis d'or please?

CHEVALIER: Of course, Lord Ludd.

437 Barry and Chevalier. (1:29:17)

BARRY: Cinq mille.

438 Ludd. (1:29:22)

LUDD: Maintenant, tout sur le quatre.

439 Barry and Chevalier. (1:29:31)

440 Ludd. (1:29:35)

441 CU of 4 of clubs dropping out of the Chevalier's sleeve into his hand. (1:29:40)

442 Barry and the Chevalier. The Chevalier's left arm is not on the table. (1:29:41)

CHEVALIER: Rien ne va plus.

The card is flipped and Ludd loses.

443 Ludd disappointed. (1:29:48)

CHEVALIER: Le quatre est perdant.

444 The Chevalier rakes in the money. (1:29:52)

445 Ludd. (1:29:56)

CHEVALIER: Faites vos jeaux.

LUDD: Ce n'est pas important. Maintenant, je suis fatigue. Je desire diner. Allons-nous?

446 Barry and Chevalier. (1:30:15)

Barry reaches for a paper.

447 Ludd. Barry laying down the paper for him to sign. (1:30:17)

BARRY:

Excuse me, Lord Ludd. If you don't mind.

LUDD (signing): Not at all.

NARRATION: They always played on credit with any person of honour or noble lineage. They never pressed for their winnings or declined to receive promissory notes in lieu of gold. But woe to the man who did not pay when the note became due. Redmond Barry was sure to wait upon him with his bill.

428 |

429 |

430 |

431 |

432 |

433 |

434 |

435 |

436 |

437 |

438 |

439 |

440 |

441 |

442 |

443 |

444 |

445 |

446 |

447 |

448 LS Fencing duel between Barry and Ludd. (1:30:42)

NARRATION: And there were very few bad debts. It was his great skill with the sword, and readiness to use it, that maintained the reputation of the firm, so to speak.

REFEREE (or whatever you call it): En garde!

449 Ludd from Barry's right. (1:30:55)

450 Barry from behind and left of Ludd. (1:31:04)

451 Ludd from Barry's right. (1:31:08)

452 LS of the duel, the pair circling. (1:31:11)

453 Ludd from Barry's left. (1:31:17)

454 Barry from Ludd's right. (1:31:21)

455 Barry from Ludd's left. (1:31:26)

456 Ludd from Barry's right. (1:31:30)

LUDD:

I will pay you today, sir.

NARRATION: Thus, it will be seen, that their life...

457 Barry from Ludd's left. (1:31:45)

NARRATION: ...for all its splendour, was not without some danger and difficulty, requiring talent and determination for success...

449 |

450 |

451 |

452 |

453 |

454 |

455 |

456 |

457 |

|

458 LS of Castle. (1:31:53)

NARRATION: ...and one which required them to live a wandering and disconnected life. And, if the truth be told, though they were swimming upon the high tide of fortune, and prospering with the cards, they had little to show for their labour but some fine clothes and a few trinkets.

Luxury and danger. Cards, cheating (magic) and swords. Even though the Chevalier and Barry win (at cheating), even though Barry has the skill at arms to back them up, still they are represented as fleeing a shadowy mountain-top castle as if from an evil, fairy tale kingdom. The book contains many stories of Barry's adventures with the Chevalier, often darkly, bitterly comic. In the novel, as in the film, we are intended to not feel much sympathy for the nobility, even though Barry and the Chevalier are cheaters, as the nobility are also liars and thieves. Barry and the Chevalier may not take from the rich and give to the poor, but we have the feeling that they are at least practicing a profession that requires skill, rather than living idly off the work and tears of commoners. I don't believe there's a single royal or member of the upper class in the film for whom we're not supposed to have some antipathy--and yet here is the Irish Barry, an adventurer who counts himself as descended from nobility and is determined to regain that elevated status. He may be the picture of the classic American who is never "lower class" but only momentarily inconvenienced.

My first affair of honour with a man of undoubted fashion was on the score of my nobility, with young Sir Rumford Bumford of the English embassy; my uncle at the same time sending a cartel to the Minister, who declined to come. I shot Sir Rumford in the leg, amidst the tears of joy of my uncle, who accompanied me to the ground; and I promise you that none of the young gentlemen questioned the authenticity of my pedigree, or laughed at my Irish crown again.

What a delightful life did we now lead! I knew I was born a gentleman, from the kindly way in which I took to the business: as business it certainly is. For though it SEEMS all pleasure, yet I assure any low-bred persons who may chance to read this, that we, their betters, have to work as well as they: though I did not rise until noon, yet had I not been up at play until long past midnight? Many a time have we come home to bed as the troops were marching out to early parade; and oh! it did my heart good to hear the bugles blowing the reveille before daybreak, or to see the regiments marching out to exercise, and think that I was no longer bound to that disgusting discipline, but restored to my natural station.

I came into it at once, and as if I had never done anything else all my life. I had a gentleman to wait upon me, a French friseur to dress my hair of a morning; I knew the taste of chocolate as by intuition almost, and could distinguish between the right Spanish and the French before I had been a week in my new position; I had rings on all my fingers, watches in both my fobs, canes, trinkets, and snuffboxes of all sorts, and each outvying the other in elegance. I had the finest natural taste for lace and china of any man I ever knew; I could judge a horse as well as any Jew dealer in Germany; in shooting and athletic exercises I was unrivalled; I could not spell, but I could speak German and French cleverly. I had at the least twelve suits of clothes; three richly embroidered with gold, two laced with silver, a garnet-coloured velvet pelisse lined with sable; one of French grey, silver-laced, and lined with chinchilla. I had damask morning robes. I took lessons on the guitar, and sang French catches exquisitely. Where, in fact, was there a more accomplished gentleman than Redmond de Balibari? All the luxuries becoming my station could not, of course, be purchased without credit and money: to procure which, as our patrimony had been wasted by our ancestors, and we were above the vulgarity and slow returns and doubtful chances of trade, my uncle kept a faro-bank. We were in partnership with a Florentine, well known in all the Courts of Europe, the Count Alessandro Pippi, as skilful a player as ever was seen; but he turned out a sad knave latterly, and I have discovered that his countship was a mere imposture. My uncle was maimed, as I have said; Pippi, like all impostors, was a coward; it was my unrivalled skill with the sword, and readiness to use it, that maintained the reputation of the firm, so to speak, and silenced many a timid gambler who might have hesitated to pay his losings. We always played on parole with anybody: any person, that is, of honour and noble lineage. We never pressed for our winnings or declined to receive promissory notes in lieu of gold. But woe to the man who did not pay when the note became due! Redmond de Balibari was sure to wait upon him with his bill, and I promise you there were very few bad debts: on the contrary, gentlemen were grateful to us for our forbearance, and our character for honour stood unimpeached. In later times, a vulgar national prejudice has chosen to cast a slur upon the character of men of honour engaged in the profession of play; but I speak of the good old days in Europe, before the cowardice of the French aristocracy (in the shameful Revolution, which served them right) brought discredit and ruin upon our order. They cry fie now upon men engaged in play; but I should like to know how much more honourable THEIR modes of livelihood are than ours. The broker of the Exchange who bulls and bears, and buys and sells, and dabbles with lying loans, and trades on State secrets, what is he but a gamester? The merchant who deals in teas and tallow, is he any better? His bales of dirty indigo are his dice, his cards come up every year instead of every ten minutes, and the sea is his green table. You call the profession of the law an honourable one, where a man will lie for any bidder; lie down poverty for the sake of a fee from wealth, lie down right because wrong is in his brief. You call a doctor an honourable man, a swindling quack, who does not believe in the nostrums which he prescribes, and takes your guinea for whispering in your ear that it is a fine morning; and yet, forsooth, a gallant man who sits him down before the baize and challenges all comers, his money against theirs, his fortune against theirs, is proscribed by your modern moral world. It is a conspiracy of the middle classes against gentlemen: it is only the shopkeeper cant which is to go down nowadays. I say that play was an institution of chivalry: it has been wrecked, along with other privileges of men of birth. When Seingalt engaged a man for six-and-thirty hours without leaving the table, do you think he showed no courage? How have we had the best blood, and the brightest eyes, too, of Europe throbbing round the table, as I and my uncle have held the cards and the bank against some terrible player, who was matching some thousands out of his millions against our all which was there on the baize! when we engaged that daring Alexis Kossloffsky, and won seven thousand louis in a single coup, had we lost, we should have been beggars the next day; when HE lost, he was only a village and a few hundred serfs in pawn the worse. When, at Toeplitz, the Duke of Courland brought fourteen lacqueys, each with four bags of florins, and challenged our bank to play against the sealed bags, what did we ask? 'Sir,' said we, 'we have but eighty thousand florins in bank, or two hundred thousand at three months. If your Highness's bags do not contain more than eighty thousand, we will meet you.' And we did, and after eleven hours' play, in which our bank was at one time reduced to two hundred and three ducats, we won seventeen thousand florins of him. Is THIS not something like boldness? does THIS profession not require skill, and perseverance, and bravery? Four crowned heads looked on at the game, and an Imperial princess, when I turned up the ace of hearts and made Paroli, burst into tears. No man on the European Continent held a higher position than Redmond Barry then; and when the Duke of Courland lost, he was pleased to say that we had won nobly; and so we had, and spent nobly what we won.

... In those great days of our fortune, I calculate that we lost no less than fourteen thousand louis by such failures of payment. A princess of a ducal house gave us paste instead of diamonds, which she had solemnly pledged to us; another organised a robbery of the Crown jewels, and would have charged the theft upon us, but for Pippi's caution, who had kept back a note of hand 'her High Transparency' gave us, and sent it to his ambassador; by which precaution I do believe our necks were saved. A third lady of high (but not princely) rank, after I had won a considerable sum in diamonds and pearls from her, sent her lover with a band of cut-throats to waylay me; and it was only by extraordinary courage, skill, and good luck, that I escaped from these villains, wounded myself, but leaving the chief aggressor dead on the ground: my sword entered his eye and broke there, and the villains who were with him fled, seeing their chief fall. They might have finished me else, for I had no weapon of defence.

Thus it will be seen that our life, for all its splendour, was one of extreme danger and difficulty, requiring high talents and courage for success; and often, when we were in a full vein of success, we were suddenly driven from our ground on account of some freak of a reigning prince, some intrigue of a disappointed mistress, or some quarrel with the police minister. If the latter personage were not bribed or won over, nothing was more common than for us to receive a sudden order of departure; and so, perforce, we lived a wandering and desultory life.

In Kubrick's early script, Ludd would be the character Dascher, which accounts for the beauty spot in the middle of his forehead. They dueled with pistols, Barry (Roderick) allowing Dascher to try a second shot after first missing him. Dascher missed again. Barry confidently discharged his first shot into the air and then took aim and hit Dascher in the center of the forehead. In the film, it's as if Ludd retains the mark of this, a reincarnation of Dascher and his beauty mark as a momento from his former life.

The location, according to many sources, is Hohenzollern Castle, dating back to 1061. The original castle was destroyed in 1423, rebuilt, then during the Thirty Years War was converted into a fortress and turned into ruins, not to be rebuilt again until after 1850 by King Frederick William IV. Hidden in Kubrick's films are usually subterranean realms, the underworld, and this castle, is as one of them. In photos it is a tan color, but Kubrick gives it as dark and forbidding, in shadow even during the day.

If we look at the two women who sit to either side of Ludd it becomes apparent they may be twins or are so similar in appearance they are to be perhaps taken as twins.

A flip is had with the dealing of the cards. In shot 441 we are shown a close-up of the Chevalier dropping a 4 of clubs into his right hand beneath the table edge, so his arm would be off the table. Then in the next shot we see instead the Chevalier's left hand is off the table. He raises it onto the table, and the drop then would be made of the card onto the pile over which he holds his left hand. He then draws from that pile, with his right, the four of clubs.

The name Ludd is neither in the novel nor the early script. Aren't Barry and the Chevalier still in Europe? Who is this Lord Ludd? I've wondered if it's connected with the mythical Irish king, Nuada (Alregtlam, meaning silver hand/arm), the Welsh name being Nudd or Lludd. He was king of the Tuatha De Danann, people of an Otherworld domain (pre-Christian deities) who displaced the Fir Bolg of Ireland, a battle during which he lost his arm. As he was no longer physically whole, he was no longer considered suitable for kingship and was replaced by a half-Fomorian prince. Later his arm was replaced with a silver one over which he grew flesh, and he became king again. So why Ludd? Is there any connection at all to Nuada? I don't know.

It may be that Kubrick may have been making a play on the name Lyndon in Ludd. For though Lyndon derives from Hill of Linden (Lime) Trees, London is an alternative spelling, and an origin for London was until recently thought to have been perhaps derived from King Lud who was likely connected with King Ludd. This would make sense as we go from the dark kingdom of Ludd, and his owing them considerable money, to the bright, white castle where Barry meets Lady Lyndon.

The four of clubs by which they win the last hand, can mean marriage, the Rider-Waite card showing a couple near a wreath of canopy of flowers and fruits binding together four wands situated like the poles of a marriage canopy. Beyond them is a large, light gray castle. It is also noted as being more like a sukkah for a harvest festival, which suits the card's meaning of harmony, prosperity, peace, domestic harvest-home. Peace and harmony will not be found with Lady Lyndon, but then Lord Lyndon will warn Barry to instead marry someone who will be a lifelong friend and helpmate, and Barry from the beginning of their marriage does all that he can to insult Lady Lyndon.

The Barber of Seville debuted in 1816 under the title "The Futile Precaution". It begins with deception, the Count Almaviva masquerading as a young student, Lindoro, in order that he may win the love of a woman named Rosina for himself and be assured she is not simply attracted to his money. Rosina is the ward of a man named Bartolo who plans himself to marry her when she comes of age. Figaro, the barber, who was once a servant of the Count's, is hired to help Alamviva meet Rosina. Figaro advises him to dress as a drunken soldier and request housing for the night at Bartolo's. Alamviva meets Rosina but Bartolo is suspicious and ejects him. In Act 2, Almaviva tries to gain access to Rosina as a singing tutor. He again ends up being driven out. Now Bartolo decides to marry Rosina that evening, and convinces her that Lindoro is just a "flunky" of Almaviva. There's a thunderstorm. The Count and Figaro gain access to Rosina by a ladder to her balcony and Almaviva reveals to her his true identity. When they try to leave together, the ladder is found to have been removed. Rosina and Almaviva manage to be married right there before Bartolo can force Rosina to marry him, but Bartolo is allowed to keep her dowry.

I'm less interested in the Barber of Seville than in its sequel, The Marriage of Figaro, which was a denunciation of aristocratic privilege and has been viewed as "foreshadowing the French Revolution" (Wikipedia). A part of Figaro's monologue from it follows:

No, my lord Count, you shan't have her... you shall not have her! Just because you are a great nobleman, you think you are a great genius—Nobility, fortune, rank, position! How proud they make a man feel! What have you done to deserve such advantages? Put yourself to the trouble of being born—nothing more. For the rest—a very ordinary man! Whereas I, lost among the obscure crowd, have had to deploy more knowledge, more calculation and skill merely to survive than has sufficed to rule all the provinces of Spain for a century...

This is the audience. Barry, as one lost in the obscure crowd, desires to be royalty and must reply knowledge, calculation and skill. So the audience sympathizes with his determination to gain status by other means when it's not availed him by birth. Despite his eventual elevation in status through marriage, he again represents the populace as he is unable to keep his noble home and lifestyle and falls back into a commoner status of anonymous poverty.

The figure of Figaro is that of a Harlequin. Kubrick had, with The Killing imposed on it the story of Pagliacci, in which we have the clowns Pierrot and Harlequin and Columbine, Harlequin deceiving the tragic and jealous Pierrot with his wife, Columbine. Later, when Barry is informed that his son has snuck out, possibly to ride his new horse, he is shaving, and I would imagine we have there one of the reasons for this choice of music, or for Barry to be shaving which connects back with Figaro. Harlequin is a trickster figure, but over time has blended with the sad (sometimes grotesque) Pierrot. Creatures of tragedy. When Barry is shaving, his face is soaped in part, as a clown's face. And while he is shaving, his son has fallen from his horse, shattering all of Barry's dreams.

Thackeray even has Sir Charles compare Barry to a barber. Perhaps that is the reason for Kubrick's use of The Barber of Seville.

Barbers were once associated with prostitution, and it seems sensible that a little of this is retained in The Barber of Seville. Kubrick, in Killer's Kiss, associates the Pleasure Land dance hall where Gloria works with a barber shop. I explore the peculiar way he does so in the analysis of that film.

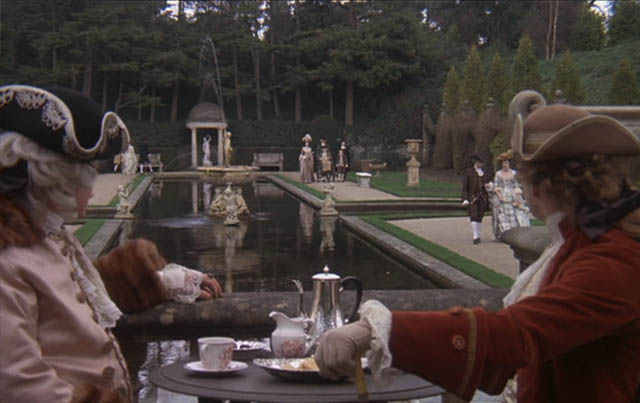

459 LS of white castle and gardens before. (1:32:17)

Begin music. Piano Trio in E Flat. Opus 100. Schubert.

460 People walking about the gardens beside a reflecting pool. (1:32:24)

NARRATION: Five years in the Army, and considerable experience of the world had by now dispelled any of those romantic notions regarding love with which Barry commenced life. And he began to have it in mind, as many gentlemen had done before him, to marry a woman of fortune and condition.

Zoom in on the Lyndons.

NARRATION: And, as such things so often happen, these thoughts mostly coincided with his setting sight upon a lady who will henceforth play a considerable part

in the drama of his life.

This is, in a way, a several part zoom, speeding up at the end, and reminds of shot 252 in this way.

NARRATION: The Countess of Lyndon, Viscountess Bullingdon of England, Baroness Castle Lyndon of the kingdom of lreland. A woman of vast wealth and great beauty.

461 CU of Barry. (1:33:29)

NARRATION: She was the wife of the right honorable Sir Charles...

462 Another view of the Lyndons strolling the garden. (1:33:37)

NARRATION: ...Reginald Lyndon, Knight of the Bath, and Minister to George the III at several of the smaller Courts of Europe, a cripple, wheeled about in a chair, worn out by gout and a myriad of diseases. Her Ladyship's Chaplain, Mr. Runt, acted in the capacity of tutor to her son, the little Viscount Bullingdon, a melancholy little boy much attached to his mother.

461 |

462 |

463 The gaming table, Lady Lyndon from Barry's right. (1:34:14)

464 Barry and the Chevalier. (1:34:41)

465 The Lady Lyndon and Runt. (1:34:48)

466 CU Barry. (1:35:08)

467 Lady Lyndon and Runt. (1:35:16)

Runt notices her occasional glances at Barry.

468 CU Barry. (1:36:32)

469 Lady Lyndon and Runt. (1:35:57)

470 CU Barry. (1:35:43)

471 CU of Lady Lyndon. (1:35:50)

472 CU of Barry. (1:35:58)

473 CU of Lady Lyndon. (1:36:03)

474 Lady Lyndon and Runt. (1:36:19)

LADY LYNDON: Samuel, I'm going outside for a breath of air.

RUNT: Yes, My Lady.

475 CU of Barry. (1:36:34)

464 |

465 |

466 |

467 |

468 |

469 |

470 |

471 |

472 |

473 |

474 |

475 |

476 MLS of Lady Lyndon strolling onto an exterior porch. (1:36:36)

477 MS of Lady Lyndon. We view Barry passing down an interior hall behind. (1:36:45)

478 Side view of Barry approaching Lady Lyndon. She turns and faces him and they kiss. (1:37:11)

479 LS of the pair boating, another boat with red sails passing. (1:38:10)

NARRATION: To make a long story short, six hours after they met, her Ladyship was in love. And once Barry got into her company he found innumerable occasions

to improve his intimacy and was scarcely out of her Ladyship's sight.

480 Barry and Lady Lyndon strolling in a garden past a pool with fountain. (1:38:40)

The shot pans right to look over a pool and river.

481 A gaming table of 4, Barry approaching and addressing. (1:39:35)

BARRY: Good evening, gentlemen. Sir Charles.

482 MS Sir Charles. (1:39:40)

SIR CHARLES:

Good evening, Mr. Barry. Have you done with my Lady?

483 Barry from beyond a 3/4 view of the table. (1:39:47)

BARRY: I beg your pardon?

SIR CHARLES: Come, come, sir. I'm a man who would rather

be known as a cuckold than a fool.

The loud ticking of a clock can be heard in the background.

BARRY: I think, Sir Charles Lyndon,

that you've had too much to drink.

484 MCU Sir Charles. (1:40:00)

SIR CHARLES (laughing): What?

BARRY: As it happens, your Chaplain, Mr. Runt,

introduced me into the company of your Lady to advise me on a religious matter, of which she is a considerable expert.

485 LS of the table, Sir Charles guffawing then coughing. (1:40:12)

SIR CHARLES: He wants...to step into my shoes. He wants to step into my shoes!!

486 CU of Barry. (1:40:25)

SIR CHARLES: Is it not a pleasure, gentlemen, for me, as I am drawing near the goal...

487 The table from 3/4 left. (1:40:31)

SIR CHARLES: ...to find my home such a happy one, my wife so fond of me, that she is even now thinking of appointing a successor?

488 Sir Charles. (1:40:38)

SIR CHARLES: Isn't it a comfort to see her like a prudent housewife getting everything ready for her husband's departure?

489 The table from 3/4 right. (1:40:44)

BARRY: I hope you're not thinking of leaving us soon, Sir Charles?

490 MCU Sir Charles. (1:40:48)

SIR CHARLES: Not so soon, my dear, as you may fancy, perhaps. Why, man, I've been given over many times these four years. And there was always a candidate or two waiting to apply for the situation. I'm sorry for you, Mr. Barry. It grieves me to keep you or any gentleman waiting. Had you not better arrange with my doctor or have the cook flavour my omelette with arsenic, eh? What are the odds, gentlemen, that I live to see Mr. Barry hang yet?

491 Shot of the table from 3/4 right. (1:41:21)

BARRY: Sir, let those laugh that win. Gentlemen.

492 LS of Barry turning and exiting. (1:41:31)

Sir Charles chokes.

493 MS of Sir Charles becoming ill. (1:41:36)

Trying to open a bottle he spills pills everywhere as he has a heart attack.

GENTLEMAN: I'll get a surgeon.

GENTLEMAN 2: Have some brandy, Sir Charles.

NARRATION: From a report in The Saint James' Chronicle: "Died at Spa in the kingdom of Belgium, the Right Honorable Sir Charles Reginald Lyndon, Knight of the Bath, Member of Parliament, and for many years His Majesty's Representative at various European Courts. He has left behind him a name which is endeared to all his friends."

482 |

483 |

484 |

485 |

486 |

487 |

488 |

489 |

490 |

491 |

492 |

493 |

Black screen about 1:42:21

494 INTERMISSION (1:42:24)

1:42:30 Piano.

I will quote at some length from the book to show that in the novel the courtship of Lady Lyndon was a protracted affair and that the relationship between Barry and Sir Charles was not so immediately antagonistic as in the film, if even bitter at all. For Sir Charles certainly came to recognize Barry's opportunistic hopes, but even before then, as well as after this realization, he complained about Lady Lyndon as having deprived him of life, and that she would certainly do the same to his successor.

Discussion will be later had on what happens with Kubrick's altering Lady Lyndon so that she is not only a noble, she is also a noble woman, for in the book she was less so and it seems perhaps not solely due Barry's not-so-trustworthy perspective.

As for the reader having always to see through Barry's distortions in order to divine the true story, the majority of his account must be reliable or reading the book would be a futile enterprise, and would have been a pointless vehicle for Thackeray to address the horrors of war and the parasitic nature of the aristocracy.

Five years in the army, long experience of the world, had ere now dispelled any of those romantic notions regarding love with which I commenced life; and I had determined, as is proper with gentlemen (it is only your low people who marry for mere affection), to consolidate my fortunes by marriage.

...

In evoking the recollection of these kind and fair creatures I have nothing but pleasure. I would I could say as much of the memory of another lady, who will henceforth play a considerable part in the drama of my life,—I mean the Countess of Lyndon; whose fatal acquaintance I made at Spa, very soon after the events described in the last chapter had caused me to quit Germany.

Honoria, Countess of Lyndon, Viscountess Bullingdon in England, Baroness Castle Lyndon of the kingdom of Ireland, was so well known to the great world in her day, that I have little need to enter into her family history; which is to be had in any peerage that the reader may lay his hand on. She was, as I need not say, a countess, viscountess, and baroness in her own right. Her estates in Devon and Cornwall were among the most extensive in those parts; her Irish possessions not less magnificent; and they have been alluded to, in a very early part of these Memoirs, as lying near to my own paternal property in the kingdom of Ireland: indeed, unjust confiscations in the time of Elizabeth and her father went to diminish my acres, while they added to the already vast possessions of the Lyndon family.

The Countess, when I first saw her at the assembly at Spa, was the wife of her cousin, the Right Honourable Sir Charles Reginald Lyndon, Knight of the Bath, and Minister to George II. and George III. at several of the smaller Courts of Europe. Sir Charles Lyndon was celebrated as a wit and bon vivant: he could write love-verses against Hanbury Williams, and make jokes with George Selwyn; he was a man of vertu like Harry Walpole, with whom and Mr. Grey he had made a part of the grand tour; and was cited, in a word, as one of the most elegant and accomplished men of his time.

I made this gentleman's acquaintance as usual at the play-table, of which he was a constant frequenter. Indeed, one could not but admire the spirit and gallantry with which he pursued his favourite pastime; for, though worn out by gout and a myriad of diseases, a cripple wheeled about in a chair, and suffering pangs of agony, yet you would see him every morning and every evening at his post behind the delightful green cloth: and if, as it would often happen, his own hands were too feeble or inflamed to hold the box, he would call the mains, nevertheless, and have his valet or a friend to throw for him. I like this courageous spirit in a man; the greatest successes in life have been won by such indomitable perseverance.

...

He was a very free-spoken man (the gentry of those days were much prouder than at present), and used to say to me in his haughty easy way, 'Hang it, Mr. Barry, you have no more manners than a barber, and I think my black footman has been better educated than you; but you are a young fellow of originality and pluck, and I like you, sir, because you seem determined to go to the deuce by a way of your own.'

...

'Stick to the trumps, however, my lad,' he would say, when I told him of my misfortunes in the conjugal line, and how near I had been winning the greatest fortune in Germany. 'Do anything but marry, my artless Irish rustic' (he called me by a multiplicity of queer names). 'Cultivate your great talents in the gambling line; but mind this, that a woman will beat you.'

...

'They will beat you in the long run, my Tipperary Alcibiades. As soon as you are married, take my word of it, you are conquered. Look at me. I married my cousin, the noblest and greatest heiress in England—married her in spite of herself almost' (here a dark shade passed over Sir Charles Lyndon's countenance). 'She is a weak woman. You shall see her, sir, HOW weak she is; but she is my mistress. She has embittered my whole life. She is a fool; but she has got the better of one of the best heads in Christendom. She is enormously rich; but somehow I have never been so poor as since I married her. I thought to better myself; and she has made me miserable and killed me. And she will do as much for my successor, when I am gone.'

'Has her Ladyship a very large income?' said I. At which Sir Charles burst out into a yelling laugh, and made me blush not a little at my gaucherie; for the fact is, seeing him in the condition in which he was, I could not help speculating upon the chance a man of spirit might have with his widow.

'No, no!' said he, laughing. 'Waugh hawk, Mr. Barry; don't think, if you value your peace of mind, to stand in my shoes when they are vacant.

...

Lady Lyndon wrote poems in English and Italian, which still may be read by the curious in the pages of the magazines of the day. She entertained a correspondence with several of the European savans upon history, science, and ancient languages, and especially theology. Her pleasure was to dispute controversial points with abbes and bishops; and her flatterers said she rivalled Madam Dacier in learning. Every adventurer who had a discovery in chemistry, a new antique bust, or a plan for discovering the philosopher's stone, was sure to find a patroness in her. She had numberless works dedicated to her, and sonnets without end addressed to her by all the poetasters of Europe, under the name of Lindonira or Calista. Her rooms were crowded with hideous China magots, and all sorts of objects of VERTU.

No woman piqued herself more upon her principles, or allowed love to be made to her more profusely.

...

Lady Lyndon moved about with a little court of her own. She had half-a-dozen carriages in her progresses. In her own she would travel with her companion (some shabby lady of quality), her birds, and poodles, and the favourite savant for the time being. In another would be her female secretary and her waiting-women; who, in spite of their care, never could make their mistress look much better than a slattern. Sir Charles Lyndon had his own chariot, and the domestics of the establishment would follow in other vehicles.

Also must be mentioned the carriage in which rode her Ladyship's chaplain, Mr. Runt, who acted in capacity of governor to her son, the little Viscount Bullingdon,— a melancholy deserted little boy, about whom his father was more than indifferent, and whom his mother never saw, except for two minutes at her levee, when she would put to him a few questions of history or Latin grammar; after which he was consigned to his own amusements, or the care of his governor, for the rest of the day.

...

My uncle and I talked the matter over, and speedily settled upon a method for making our approaches upon this stately lady of Castle Lyndon. Mr. Runt, young Lord Bullingdon's governor, was fond of pleasure, of a glass of Rhenish in the garden-houses in the summer evenings, and of a sly throw of the dice when the occasion offered; and I took care to make friends with this person, who, being a college tutor and an Englishman, was ready to go on his knees to any one who resembled a man of fashion. Seeing me with my retinue of servants, my vis-a-vis and chariots, my valets, my hussar, and horses, dressed in gold, and velvet, and sables, saluting the greatest people in Europe as we met on the course, or at the Spas, Runt was dazzled by my advances, and was mine by a beckoning of the finger. I shall never forget the poor wretch's astonishment when I asked him to dine, with two counts, off gold plate, at the little room in the casino: he was made happy by being allowed to win a few pieces of us, became exceedingly tipsy, sang Cambridge songs, and recreated the company by telling us, in his horrid Yorkshire French, stories about the gyps, and all the lords that had ever been in his college. I encouraged him to come and see me oftener, and bring with him his little viscount; for whom, though the boy always detested me, I took care to have a good stock of sweetmeats, toys, and picture-books when he came.

I then began to enter into a controversy with Mr. Runt, and confided to him some doubts which I had, and a very very earnest leaning towards the Church of Rome. I made a certain abbe whom I knew write me letters upon transubstantiation, &c., which the honest tutor was rather puzzled to answer. I knew that they would be communicated to his lady, as they were; for, asking leave to attend the English service which was celebrated in her apartments, and frequented by the best English then at the Spa, on the second Sunday she condescended to look at me; on the third she was pleased to reply to my profound bow by a curtsey; the next day I followed up the acquaintance by another obeisance in the public walk; and, to make a long story short, her Ladyship and I were in full correspondence on transubstantiation before six weeks were over.

...

I joined Sir Charles at the casino, he received me with a yell of laughter, as his wont was, and introduced me to all the company as Lady Lyndon's interesting young convert. This was his way. He laughed and sneered at everything. He laughed when he was in a paroxysm of pain; he laughed when he won money, or when he lost it: his laugh was not jovial or agreeable, but rather painful and sardonic.

'Gentlemen,' said he to Punter, Colonel Loder, Count du Carreau, and several jovial fellows with whom he used to discuss a flask of champagne and a Rhenish trout or two after play, 'see this amiable youth! He has been troubled by religious scruples, and has flown for refuge to my chaplain, Mr. Runt, who has asked for advice from my wife, Lady Lyndon; and, between them both, they are confirming my ingenious young friend in his faith. Did you ever hear of such doctors, and such a disciple?'

''Faith, sir,' said I, 'if I want to learn good principles, it's surely better I should apply for them to your lady and your chaplain than to you!'

'He wants to step into my shoes!' continued the knight.

'The man would be happy who did so,' responded I, 'provided there were no chalk-stones included!' At which reply Sir Charles was not very well pleased, and went on with increased rancour. He was always free-spoken in his cups; and, to say the truth, he was in his cups many more times in a week than his doctors allowed.

'Is it not a pleasure, gentlemen,' said he, 'for me, as I am drawing near the goal, to find my home such a happy one; my wife so fond of me, that she is even now thinking of appointing a successor? (I don't mean you precisely, Mr. Barry; you are only taking your chance with a score of others whom I could mention.) Isn't it a comfort to see her, like a prudent housewife, getting everything ready for her husband's departure?'

'I hope you are not thinking of leaving us soon, knight?' said I, with perfect sincerity; for I liked him, as a most amusing companion. 'Not so soon, my dear, as you may fancy, perhaps,' continued he. 'Why, man, I have been given over any time these four years; and there was always a candidate or two waiting to apply for the situation. Who knows how long I may keep you waiting?' and he DID keep me waiting some little time longer than at that period there was any reason to suspect.

...

After I once got into the house on the transubstantiation dispute, I found a dozen more occasions to improve my intimacy, and was scarcely ever out of her Ladyship's doors. The world talked and blustered; but what cared I?

...

In fact, the doctors tinkered him up for a year.

...

I shall pass over the events of the year that ensued before I again saw her. She wrote to me according to promise; with much regularity at first, with somewhat less frequency afterwards. My affairs, meanwhile, at the play-table went on not unprosperously, and I was just on the point of marrying the widow Cornu (we were at Brussels by this time, and the poor soul was madly in love with me,) when the London Gazette was put into my hands, and I read the following announcement:—

'Died at Castle-Lyndon, in the kingdom of Ireland, the Right Honourable Sir Charles Lyndon, Knight of the Bath, member of Parliament for Lyndon in Devonshire, and many years His Majesty's representative at various European Courts. He hath left behind him a name which is endeared to all his friends for his manifold virtues and talents, a reputation justly acquired in the service of His Majesty, and an inconsolable widow to deplore his loss. Her Ladyship, the bereaved Countess of Lyndon, was at the Bath when the horrid intelligence reached her of her husband's demise, and hastened to Ireland immediately in order to pay her last sad duties to his beloved remains.'

Most telling, in the novel, when Sir Charles realized Barry's laying a foundation for courtship of Lady Lyndon, he instead encouraged Barry to find and marry a friend. This is not the kind of advice one would expect from an enemy. Sir Charles is even Thackeray's oracular voice attempting to guide Barry onto a road where he might find a measure of happiness and fulfillment.

When Lady Lyndon leaves the gaming table to meet Barry outside, the man who takes her place looks much like one of the men who is with Sir Charles when he has his fatal attack. The actor who takes her place is George Holdcroft. I wonder if however the man who is with Sir Charles is Hans Meyer.

We shouldn't forget how Barry's love interest is coincidentally a Lyndon, and that the Lyndons were said to have come into possession of the old Barry estate by both marriage and violence, an upset still felt very keenly by Barry descendants. Sir Charles was a distant relative of Barry. So, too, was Lord Bullingdon. Is it coincidence that places Lady Lyndon in Barry's path so that he not only uses her to establish his place among the upper class, he also regains the ancestral estate, or is he drawn to her only through cold calculation and self will? Though Kubrick doesn't give this angle, his films have repeating cycles, deja vu, and we may even find in Barry a predecessor of Jack in The Shining, someone who, through his ancestral claim, when he wanders the Lyndon estate, may have the feeling of having been there before, of knowing what was to be found around every corner. All that Lady Lyndon possessed he would conceive of as being his and that he was repatriating it.

The below passage was already given in the first section, but it's good to refresh one's memory as Barry engages in his pursuit.

That very estate which the Lyndons now possess in Ireland was once the property of my race. Rory Barry of Barryogue owned it in Elizabeth's time, and half Munster beside. The Barry was always in feud with the O'Mahonys in those times; and, as it happened, a certain English colonel passed through the former's country with a body of men-at-arms, on the very day when the O'Mahonys had made an inroad upon our territories, and carried off a frightful plunder of our flocks and herds.

This young Englishman, whose name was Roger Lyndon, Linden, or Lyndaine, having been most hospitably received by the Barry, and finding him just on the point of carrying an inroad into the O'Mahonys' land, offered the aid of himself and his lances, and behaved himself so well, as it appeared, that the O'Mahonys were entirely overcome, all the Barrys' property restored, and with it, says the old chronicle, twice as much of the O'Mahonys' goods and cattle.

It was the setting in of the winter season, and the young soldier was pressed by the Barry not to quit his house of Barryogue, and remained there during several months, his men being quartered with Barry's own gallowglasses, man by man in the cottages round about. They conducted themselves, as is their wont, with the most intolerable insolence towards the Irish; so much so, that fights and murders continually ensued, and the people vowed to destroy them.

The Barry's son (from whom I descend) was as hostile to the English as any other man on his domain; and, as they would not go when bidden, he and his friends consulted together and determined on destroying these English to a man.

But they had let a woman into their plot, and this was the Barry's daughter. She was in love with the English Lyndon, and broke the whole secret to him; and the dastardly English prevented the just massacre of themselves by falling on the Irish, and destroying Phaudrig Barry, my ancestor, and many hundreds of his men. The cross at Barrycross near Carrignadihioul is the spot where the odious butchery took place.

Lyndon married the daughter of Roderick Barry, and claimed the estate which he left: and though the descendants of Phaudrig were alive, as indeed they are in my person,[Footnote: As we have never been able to find proofs of the marriage of my ancestor Phaudrig with his wife, I make no doubt that Lyndon destroyed the contract, and murdered the priest and witnesses of the marriage.—B. L.] on appealing to the English courts, the estate was awarded to the Englishman, as has ever been the case where English and Irish were concerned.

Thus, had it not been for the weakness of a woman, I should have been born to the possession of those very estates which afterwards came to me by merit, as you shall hear. But to proceed with my family, history...

The love triangle of Pierrot, Columbine and Harlequin is realized in Pierrot as the grotesque, jealous Sir Charles, who acknowledges himself as the cuckold. The heavy make-up is supposed to be read as only factual for the time, but effects the distancing demeanor of the mask. (The flesh and blood Lady Lyndon, observed beside the dying Bryan's bed, and when she attempts suicide, becomes all the more vulnerable and personable due being without her makeup, her wigs, her elaborate dresses.) We can look upon the confrontation between Barry and Sir Charles as a duel, Barry quite literally killing Sir Charles through knowledge of his character and frailties, aware that a highly antagonized Sir Charles was one in a position to die from a heart attack. We know this, watching the film, during the event, but afterward, the story continuing, we are likely to forget.

In Eyes Wide Shut, a scene at the orgy is reminiscent of Barry and Lady Lyndon's kiss.

The Eyes Wide Shut encounter in the hall is a little like the shadow version of the fairy tale Barry and Lady Lyndon. It always seemed peculiar to me the manner in which Bill holds the hands of the black feather woman, but makes sense if we look back to Barry Lyndon and how Barry holds Lady Lyndon's hands.

Though I've read that Bill's mask was supposedly modelled on Ryan O'Neal's face circa Barry Lyndon, I've never been quite able to see this. But I do see how Barry Lyndon might be compared to another character in Eyes Wide Shut vis-a-vis a mask-like appearance.

This is the little Pierrette, as she is described in the book upon which Eyes Wide Shut is based. The one who encourages Bill to rent, rather than a regular cloak, one lined with ermine, as if he is a noble or aspires to be one. When Bill returns a second time, her doll-like appearance emphasized, she seems almost to be a mocking, taunting puppet. But she is also, alternatively, a blank, a riddle, her exterior offering no clue to what thoughts are harbored behind her gaze, just as Barry is a throughly unsearchable creature in many respects, especially when in paint but also when not in makeup. He bluffs well. The final confrontation with Sir Charles happens in the same setting as when Potzdorf and his uncle press Barry into serving as a spy for them. His disposition there displays nothing of his interior, no emotion, no personality, only the response expected of him, which is that which will best serve him and his self-preservational instincts.

Having earlier noted the seeming twins to either side of Lord Ludd, it has occurred to me that Kubrick's selection of Murray Melvin to play Lord Runt seems to provide a masculine counterpart for Lady Lyndon. In the book, Runt disappears after the marriage, but before it he is described as being wholly won over by Barry. In the film, Runt begins skeptical and stays skeptical. When he notices the Lady's subdued response to Barry at the gaming table, he immediately stiffens, examining Barry as a foe. Jealousy? We take for granted that he is likely gay, and as Lady Lyndon's spiritual advisor he seems wholly devoted to her, and she in turn provides a frame for his life. But the look he gives Barry is also a knowing one, as if he is aware of what drives Barry and that he isn't to be trusted.

Murray Melvin, in the 1961 film A Taste of Honey, plays a gay man, Jeffrey, who befriends Jo, a teenager who has been ousted from her home by her neglectful mother's new romantic attachment. The two meet and as outcasts befriend one another, moving in together. When Jo learns she is pregnant he excitedly devotes himself to caring for her when she will not care for herself, making plans for her child when she will not. He feeds her. He makes the apartment into a home. He's a marvelous character, creating their future as a family. But Jo is so despondent that he reasons she must need her mother as well. Though he's aware Jo's mother, Helen, is problematic, in the hope she may lend Jo support, he visits and lets her know that Jo is pregnant. The mother consents to see Jo. When mother and daughter meet again, they furiously argue but reconcile after a fashion. And just in time, because the mother's lover leaves her, and, assured of a home, she suddenly shows up to live with Jo.

Jo's mother tells her how she has ordered a "beautiful cart" for the baby. Jo points out that Jeffrey has already got a cart for the baby. The mother's only response is, "It's old fashioned, isn't it?"

Jealous of Jeffrey, Helen makes it only too obvious he isn't welcome now that she is here. Jeffrey, having put Jo in contact with her mother, has worked himself out of a family. He packs and leaves a note for Jo rather than telling her personally he is going. Jo's mother hands him the crib and tells him to take it with him, a terrifically cruel gesture.

I've wondered if Murray's wonderful turn as Jo's helpmate was an influence in his becoming Lady Lyndon's reverend, for though we are at times suspicious of him, he is protective of her and it's obvious that if she is likely to confide in anyone it will be Runt.

Curiously, in Eyes Wide Shut, when Bill and Alice go Christmas shopping with Helena, she picks out a baby carriage as perfect for "Sabrina". Alice's response is, "It's old fashioned." Just as Helen said in A Taste of Honey.

One of the names by which Lady Lyndon is addressed in the novel is Callisto. Callisto, in myth, was a virgin devotee of Artemis. Wikipedia has it that Zeus "disguised himself as Artemis herself, in order to lure her into his embrace". When Artemis discovered that Callisto was pregnant, she turned her into a bear and she gave birth to Arcas. How she died is up for grabs, but she and her son were placed in the sky as Ursa Major and Ursa Minor. One story is that her son, not knowing his mother in her bear form, happened upon her at age 16 and was about to kill her when Zeus placed them both in the sky as a means of avoiding the matricide. She's also a nymph of Lycaon, a king of Arcadia, which makes them wolves rather than bear shape-shifters. When Zeus, disguised as a human, visited Lycaon, Lycaon served him the flesh of his own son to test his omniscience. For this crime, Zeus changed Lycaon into a wolf, and all his offspring, thus the wolf was a tribal totem animal. Sometimes the sacrificial victim is instead Arcas who was subsequently brought back to life, and he later accidentally hunted his mother. In any case, she is associated with the motif of the sacrificed child, to be compared with Isaac. The Greeks and Romans typically had the gods abjuring such sacrifices in horror, such as eventually with the story of Idomeneo, the opera that plays when Barry receives his reward for saving Potzdorf, and again when he exits Prussia in the disguise of the Chevalier. That story also has the promise of a child sacrifice similar to the story of Iphigenia (who is also associated with the bear cult of Artemis, Artemis, Brauronia). Instead it's Idomeneo, saved from ship-wreck and drowning, who promises to sacrifice the first thing he sees to Neptune, which of course turns out to be his son. As I relate at the end of the previous section, Idomeneo commands his son to leave and never return, instead of making the sacrifice. The bewildered son eventually learns the reason for this when a sea-dragon bothers the area due Idomeneo not keeping his promise. The son, Idamante, offers himself up for sacrifice, at which point Neptune intervenes and instead transfers the throne from Idomeneo to Idamante and his lover Ilia.

We have in The Shining references to the sacrifice of Isaac and I discuss them there and their significance. So do we also have them here, embellishing a story in which Barry and the Lady lose their son. She would also lose her first son, Bullingdon, to a duel with Barry, but for the fact that Barry refuses to shoot Bullingdon. Ironically, it is this act of compassion that ushers in his complete downfall.

I've earlier related how Barry, at this spa, enters into a kind of fairy tale kingdom. Even his ancestral home. Via Arcas and Lycaon we enter the realm of Arcadia, which has become known as a utopia, but is also associated with Et Arcadia ego, Even in Arcadia, there am I. The persistance and inevitability of death. Inescapable.

Most frequently in myth we read that Theseus, on his way to fight the Minotaur, outfitted his ship with a black sail. In the event that he was successful, his father, Aegeus, would know by his ship returning with a white sail. But Theseus forgot to change the sail and his father threw himself off a cliff. I also read that instead of the white sail, he was instead to fly a red sail. In this case, however, the red sail is due to a proofing coat that was put on sails after several years.

Dunrobin Castle in Scotland is the exterior, which looks like the good fairy tale counterpart to Hohenzollern Castle, taking us from the one in the shadows to this gleaming white edifice. The reflecting pool is the Italian Garden at Compton Acres, 164 Canford Cliffs Road, Poole, Dorset. The gardens in which Barry courts Lady Lyndon are the gardens of Blenheim Palace.

Just so you know, the statue before which Lady Lyndon and Sir Charles pass immediately before Barry turns to look at them is one of Bacchus as a youth.

The statue of the male nude that's in the foreground as they walk through the Blenheim water terrace is of a male gladiator. An Alamy photo shows it is certainly this statue though the one now on display has a shield and sword, whereas in the film we see neither shield nor sword. Was it later replaced?

Approx 10,100 words or 21 single-spaced pages. A 77 minute read at 130 wpm.

Next: Barry Lyndon Analysis - Part 5

Go to Table of Contents for Analysis of Barry Lyndon

Link to the main TOC page for all the analyses