Return to Table of Contents for films

The watery world of all the sub-texts that inform reality, are the under-pinnings of our reality, which are actively denied, unspoken, or simply not known--Altman wafted into that territory with opium-fueled escapism at the end of McCabe and Mrs. Miller, suggesting that Mrs. Miller, having chosen to submerge herself in a smoky opium haze, is on some level even unconsciously aware that Mr. McCabe, her business partner and lover (despite the fact he pays her for sex) has been murdered, his body left to be submerged and freeze in piling snow. It is no condemnation of her. Reality is ugly for everyone in the isolated 19th century, Pacific Northwest mining town, stuck deep in the woods, and Mrs. Miller had aided McCabe in making it a little more civilized and pleasant via a brothel that enforced some measure of self-care, attended to hygiene, offered baths, music, and work. It wasn't perfect, but it was better than what had been. Though business people, they are a gentler sort, humanists at heart, and thus have no refuge when corporate interests take notice of their success and arrive, in the form of the ruthless Harrison Shaughnessy Mining Company, determined to steal what they've built, around which the individuals in the area have cohered to become a town that with unified effort will save the neglected but soaring architecture of the town's church from fire in the very hour that McCabe is murdered by assassins hired by Harrison Shaughnessy. How had the fire started? McCabe had hidden in the church, but the pastor had stolen his shotgun and forced him out, even knowing that McCabe needed the gun for his survival. The pastor later mistaken for McCabe and killed by one of the assassins, the rifle blast had shattered the lamp he held so its flame escaped into the church. The town celebrates their victory even as they unknowingly stand on the cusp of a different future, one managed by Harrison Shaughnessy. Also on that cusp, Mrs. Miller, in the opium den, examines the crackle glaze on a ceramic bottle and, diving into the particular, rises above the world. The vase becomes Earth, its atmosphere glowing blue-white, excited by the sun. What at first seemed escapism becomes a religious moment in which a measure of peace is found, and perhaps some resolution in loss through a refined transcendence that brings her in contact with the whole.

The world of 3 Women may be less overtly violent, but the psychological content of its dreamy sub-texts is such that their waves churn up only nightmares. How ably they reflect the reality of the time is remarkable, as Hollywood almost always, in its method of manufacturing stories, distorts places, eras, cultures and people in its efforts to anchor us, stabilize and create connection for the viewer. This is done by setting us outside the tableaux in that we are typically afforded multiple streams of information and back story manufacturing an artificial sense of omniscience while also depriving us of knowledge in the interest of the creation of "plot" and suspence, the action of moving us from one stage of unfolding action to the next, everything relevant to and leading into expectations that are in concert with and justify the final reveal, even if it is intended to surprise. Of course, Altman must do a certain amount of the same, but he distances and destabilizes enough that the strangeness of the culture is set in high relief, our familiarity with all aspects of it severed.

We ride the peculiar bow-tails of Pinky Rose into the film, who is situated to be the protagonist to whom we adhere and depend upon for point-of-view and revelation of information, and yet we feel no connection to her. Millie is often interpreted as the protagonist because her realized life is the one impacted by Pinky, whose life is unrealized. Millie is relatable, whereas Pinky is a mystery. Even Altman, in his commentary, gives Millie as the protagonist, but it's Pinky who is the observer of the life in the film. In dreams, we typically lose the power to reflect on our histories, so that we just very simply "are", coping with situations as they unfold and require almost no initiating agency on our parts. Something about our nature trusts itself to having some kind of back story, only parts of which may be made accessible, so that we keep moving forward instead of plopping down and demanding, "Where am I? What am I doing here? What's going on?" If the dream informs we are moving into a new home, and we look out the rear and see it is set impossibly on the edge of a river with its water level at mid-window, we typically haven't the power to be a waking-watchful sleeper who says, "No, this isn't right, I am in a dream." We may have curiosity in our dreams. We make associations. We imagine reasons for things, though it more often seems reasons for things simply come to us as part of the story we are living. We may not like what is happening, and feel an array of emotional responses. We may try to negotiate. But there is something about our dreaming nature, which may reflect something most basic in ourselves, in which we essentially accept the story that is handed us, that this is who we are, this is the way things are, no matter its strangeness, and keep going. We try to work with the dream inside its rules, its sense of order. Altman's film captures this in the way we wake within it to its world and its characters, especially Pinky. This is the mid 1970s in which we find ourselves when we open our eyes and It is a strange world that boils down to several who become connected in their attempts to survive and negotiate the terrain, while most parts are non-negotiable constructions that are indelible and guide their fates and ours.

I'm going to skip, for the present, a description of the murals that frame the film, with which the film began, except to note how Altman gives them the appearance of being partly submerged in water, consequently moving us to a place of water. Despite Pinky being our protagonist, our first vision of the Desert Springs Rehabilitation and Geriatric Center is a perspective not available to Pinky from her situation beyond a separating window where she stands on the other side gazing on the indoor pools. In close-up, we are shown the taut backs of a younger pair of female knees guiding a much older and flaccid pair into an indoor pool. We are shown how, viewed from above, the water physically distorts what it encompasses with its density slowing light and causing it to change direction. The camera then shows us the dull, institutional pool room, lacking in any beauty, filled with elderly patients, as it pans about to Pinky (Sissy Spacek) who, in her pink dress with its short eyelet sleeves and collar and its long bow in the back, seems so very childlike and wide-eyed with fresh amazement. And perhaps she has already noticed and fixated upon Millie Lammoueaux (Shelley Duvall) who is one of the young female caretakers occasionally paired with an elder patient in the pool.

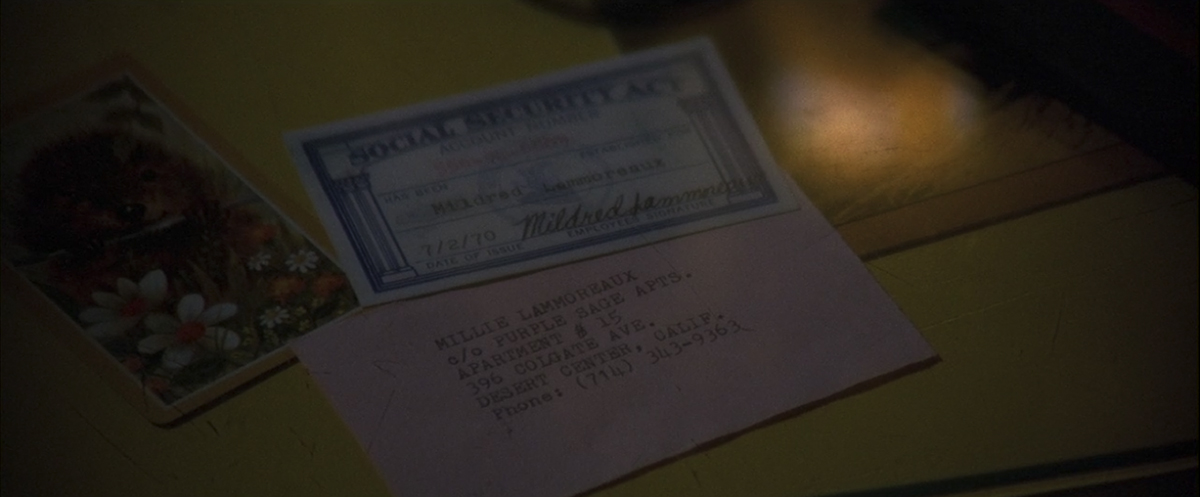

All the key women who play the therapists (except for the twins, who may have only acted in this one film and for whom there is no biographical data) were born in 1949, so about 28 when the film was released in 1977, and though Sissy Spacek presents as much younger, a certain uniformity is created despite their differences. The work, which requires only a little on-the-job training, is of a sort that was then most availed young women for whom opportunities were opening up but had still largely been brought up to be subordinate servers. Millie is one of those who views the job as a way to meet potential, professional suitors, the doctors (all male) who dine at the cafeteria in a neighboring hospital. Though we will learn that she is treated by all as if she is largely invisible, her continual stream of chatter spoken over and ignored, we shouldn't imagine that she isn't a capable and meticulous worker, more than competent enough so that she is recruited to train Pinky. But young women, as a class, are lower, and are infantilized, even when hyper-sexualized. And here they are partnered with the elderly who are presented, however sympathetically, as a non-individualized class of people who are also infantilized, and over whom some of the young women, such as Millie, even feel some control, elevated above them, having to cajole them like children into doing what is right for them. In this environment, the "real people" are the man and woman who manage the facility. We are shown that the woman hides they are intimate with one another, she refraining from touching the man as soon as they may be observed by others. And eventually we learn that they are beyond irritated by discrepancies that might draw attention to their books, and you can't blame them for that, really, except that they are assholes who cheat their workers out of every penny of their time that they can, demanding they not punch the clock until after they've dressed for work, and before they've changed out of their institutional cotton swimsuits to go home. These are the individuals who control experience in this place, Pinky and Millie working within their dream rules with no cognizance of the cogs and wheels of the gods. What are the controllers most worried by? When it's learned that Pinky gave Millie's social security number as her own, and they rake Millie over the coals for it as if she is responsible, because that's what assholes do. In the dream language of the movie, they are afraid of a confrontation with questions of identity.

By way of we, as dreamers, not belonging in this world, we experience the not-belonging of Pinky and Millie. While we are hyper-aware of the strangenesses of the environment, those who belong to it instead concentrate on those who are outliers, distancing them. Millie, we learn, hasn't seen her mother since she was eleven. Whether she died is never made clear, but it may be abandonment, for she states that she was left in the care of uncles and aunts. Her father isn't part of the picture either. As she will tell Pinky, she has no one. She's looking for her place of belonging, and her social skills show that she was likely ignored by her extended family as a child, that there was no intimacy, and that she fills in the gaps with instructions from magazines. This assessment isn't my imagining a back story or doing the drudge business of manufacturing a psychological profile for a fictional character. This is all plainly there in the film, and is worth noting for Millie's relationship to women in the broader culture who were (and ever are) continually being instructed on how to behave, how to dress from season to season, how to apply make-up, how to take off make-up, how to cook, how to have a party, what to talk about in general conversation, how to make a man like you, how to make people like you. One article says to shower, another says to bathe. One article says to walk for exercise, another to run. If you do these things then you will be accepted and part of a group. If you don't participate with others in doing these things then there's the threat of being ostracized. During that era, there were a number of magazines advising teen girls and women on every aspect of their lives--even the mothers and grandmothers having also been schooled by etiquette books and columns as they made the move from rural to a more urban culture--and much of this was branded, oriented to sell commercial products. For a woman like Millie, these magazines would be a haven of instruction, and if Altman didn't fill her apartment with them it's because we already knew how much a part of Millie's life they were as she talks incessantly about what she has learned from them. Millie, as with so many, is an avid consumer, and one who would believe she was being self-reliant and educating herself. If she follows the instructions, if she color matches and co-ordinates, if she makes herself and her environment achieve magazine picture perfection, then she can have the confidence of one who is prepared, whose due diligence to these details creates a space of inclusion. Advertising not only feeds on fears of not belonging but creates them, and promises that one will be not just presentable but even desired if instructions are followed, products are purchased. None of this is news, we are all familiar with how this works, but in respect of Millie's character it warrants stressing that all she's had for intimate family is advertising. During Millie's training of Pinky, when Pinky dives in for an appreciative hug, Millie is so thrown off balance that after glancing about to make sure no one has seen this all she can think to do is pretend nothing has happened, check the mirror and plump her curls.

We are concerned with these details, the meaning of them within the dream of this film, because the movie is concerned with how these women are demeaned, how they perceive and demean one another, and how they struggle to perceive themselves.

Millie's apartment overwhelms in memory of the movie, but it's significant, in our orientation to the characters, that the first "home" we are shown is Pinky's room at the hotel, for we have, after all, been originally united with Pinky as the central protagonist. After being introduced to Pinky's dreary room that, with the exception of the television, hasn't been updated since the 1940s, and realizing she has nothing but a suitcase with a couple of changes of clothing and a sewing machine, one can comprehend then how thrilled she would be with Millie's apartment. It's easy to find ways to mock Millie, but Pinky will see the apartment as beautiful and appreciate its comforts and the sense of stability that comes with the months of care Millie has put into decorating. She has furniture and framed things on the walls. There are matching plates, cups, and cutlery, and real ashtrays, and lamps with lampshades, and clean sheets and towels. Millie is a nester and wasn't Pinky lucky to find her.

Yes, Millie's apartment is all yellow, and her clothing is all shades of yellow and marigold, and she cooks crap, but she passionately cares about making a home for herself. Yes, she would probably make me want to scream after five minutes, but I wouldn't want to be around any of the people she attempts to ingratiate herself with either. It's actually very easy to understand Millie, and despite all the lies she tells about prospective dates and disappointments, she's likely going to be the one who is most truthful about whatever personal history she divulges. When she talks about her mother visiting her in her dreams, she's speaking truth. When she says she hasn't seen her mother since she was eleven and that she was farmed out to aunts and uncles, she's speaking truth. She doesn't say much about her past, but what she says about it is from the heart. She's not trying to impress in those moments. She's still trying to figure it out for herself, who those people were, what was true about what she was told, and who she is relative to all of it. Millie has had to fabricate herself from the bottom up out of whatever dreams she's managed to grasp as guiding stars and nurture. She is happy to have made it to this little corner of the universe and she's going to make the best of it.

In all the ways that Millie is painfully transparent in her invisibility, Pinky is obtuse in her invisibility. She originates from such a place of invisibility that Millie, while Pinky is in a coma, has difficulty finding her parents, and when they arrive it's not so much that they are old but are alien in their rural antiquity that makes them invisible to her when she goes to the bus stop to pick them up and doesn't "see" them, though they are only the individuals there. Then Pinky even denies them. She had already hedged on her circumstances, only allowing that she had been staying with "a family" in Texas and had left her things with them. However it is that Pinky has come to land in this place, she is not bringing that past with her, she wants nothing to do with it. And her parents, though they have a few stories about her, seem to have such a minimal connection with their daughter that it's startling when her mother looks at her, comatose, lying helpless in bed, and remarks that she's pretty as ever. Millie, who doesn't have parents, and is bewildered by Pinky's, unable to comprehend their behaviors, still accepts and honors them as her family, seeing to their needs. When Pinky wakes up and says she doesn't know them, and Millie reproves her for not appreciating their coming to visit, the character is less judging Pinky than speaking from her own sense of need as an orphan. As we consider this, we realize why Altman had Millie visited in dreams by a mother who brought her presents she didn't understand, just as she doesn't understand the bizarre gift Pinky's mother brings her comatose daughter--a plaque for the kitchen wall.

We can feel for Millie, and we especially do when Pinky robs her of her identity, but there's also a dark side to her. At first, she's not unhappy with having Pinky move in, for Pinky dotes upon Millie, attending to everything she says, praising all she does. In Pinky she's found an admirer who declares her perfect.

Pinky is more self-aware and attuned to the world than she appears. She behaves impishly but she does so in private, first making sure that no one is looking. When Millie returns to her apartment and looks about as she opens the door, it's to see who might be watching and hopefully admiring her. When Pinky returns to her hotel room and checks behind her as she opens the door, she's checking her back, making sure that she's not being watched, that she's safe. Around Millie, she imitates her preferences in order to win her approval, to show how they are alike, to fabricate links between them, such as sharing a dislike of tomatoes after having heard Millie tell a story about how in her dreams her mother has brought her tomatoes, which Millie doesn't understand as she doesn't like them. But Pinky doesn't wear blinders. Studying Millie, she isn't without perception of how others treat her, and when Millie's former roommate casually blows off a dinner party for which Millie has spent a day preparing, and it becomes Pinky's job to deliver the news, she is hesitant with care for how Millie will be hurt. Millie has shared her world with Pinky, but, other than her adulation, Pinky has nothing to give back to Millie. When the truth of Millie's life begins to be revealed, when she sees it becoming apparent to Pinky, Millie's language turns to degrading Pinky and blaming her as the cause for her disappointments in life. In this way Millie rejects what threatens to become pity.

Millie rejects pity because she has herself been cataloguing all the injuries, the sleights, while seeming to ignore and skate over them. She later lambasts those at the rehabilitation center for their lack of caring for Pinky during her hospitalization, declaring it a miserable place to work. So she too, all the while that she behaves with a sunny disposition, ignoring how she is ignored, is aware and hiding it.

When we begin to look at the doubles in the film, we need to be aware that Pinky is the one who catalyzes Millie into a certain degree of honesty between herself and the world. During an early one-sided conversation, Millie reveals she'd learned a new word, orator, which she didn't know existed. Eventually, she takes her employers to task and turns orator in her defense of Pinky, as well as herself. She begins to find her voice. Sure, she quits her job and loses all the stability she's worked to accrue, and this isn't the kind of film where she's rewarded, in the end, for saying what she honestly sees and thinks instead of desperately trying to fit in, but this isn't a feel-good film about how one's carefully staged life being blown up just clears the ground for one's best future to magically materialize.

Though we think of this as a film that is intolerably heated by the searing southwest sun, and infused with the intentionally cheery sunshine lemon yellows of Millie's apartment, my screengrabs startle me with how dark the cinematography of the film actually is. It seems to labor under the weight of all that light and sunny yellow that stirs up a dim grainy dust, subtly adding to the film's anxiety.

The three primary locations of action in the film are the pools of the Desert Springs rehabilitation center, the Purple Sage Apartments (we perhaps need to consider that Purple Sage--Salvia dorrii, Ute tobacco sage--is purported to have the effect of a mild hallucinogen when smoked, suiting the dreamy character of the film), and Dodge City, which, partly previously existed and was partly constructed for the film, and has the appearance of what may have once been a family road stop, Wild West themed park, complete with a miniature golf course, but it also once had a pool and so perhaps it was once a club. Being originally a family-styled road stop would fit with the ostensible real location that we see on Millie's address card, which shows the Purple Sage Apartments as being in Desert Center, California, a town midway between Phoenix and Los Angeles that was started in 1921 by a person who might be labeled a desert eccentric and largely served travelers. It also became home to workers of a large open-pit iron mine until its closure in 1982, languished to non-subsistence, and is now being resurrected as a resort. This is 1976 (filming for the bar didn't take place far from Desert center, just west of Coachella Valley) and the miniature golf course has closed, along with the pool, and there is a run-down aspect to the property that now profits mostly from dirt bike riding, a shooting range, and a bar. Apparently owned by Edgar and Willie Hart, who also own the Purple Sage Apartments, Dodge City takes its bona-fides from Edgar having been a stunt double for the actor Hugh O'Brien on the The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp television show, 229 episodes of which ran from 1955 to 1961, about 16 years before the film's action.

With no historical accuracy what-soever, just borrowing the suggested ambience of the name, Dodge city is a "double" of the original, in Kansas, where Wyatt Earp acted as an assistant marshal to his brother, Virgil, in 1876-1877, several years after the brief Wild West period that made Dodge City famous. What Wyatt Earp was initially best known for was his involvement in the gunfight at the O.K. Corral in Tombstone, Arizona. There's no reason to look at his life except to note that in his final years he went to Hollywood, where he served as a consultant for western silents, and made friends with a then well-known cowboy actor by the name of William S. Hart--and I have a difficult time believing that Altman's Dodge City Harts don't have some connection to William. Earp wanted Hart to make a movie about him, one that would tell the real story of his life, and Hart urged Earp to have his life-story written first. A friend, John Flood, took on the task, and it seems that Earp's wife, Josephine, sat in on the project and insisted on his being presented as a "church-going saint" and action hero, which Earp is said not to have wanted, but that's what happened and the poorly written, highly adulterated bio never found a publisher though Hart tried to sell it. Whatever has transpired subsequently in the telling of the tale of Wyatt Earp, there is the reality and then there are the worlds of doubles that he and others created of him, as well as his third (common law) wife, Josephine. Dying in 1944, 15 years after Earp, left penniless by her addiction to gambling, William Hart paid for Josephine's funeral and burial, along with Sid Grauman of Grauman's Theater. So the relationship between Earp and Hart was an enduring one.

He may have been a friend to Earp, but William S. Hart wasn't without his enemies. He had a rather too-close relationship with a sister, which led to his one and only wife, Winifred Westover, 35 years his junior, divorcing him after he had ordered her, then pregnant, to leave his home after six months of marriage. She was an actress, and they had met on a film in which they both starred, but she had entered the marriage agreeing to his demand she quit acting. Such was Hart's power that as part of receiving $100,000 in her divorce settlement she was forbidden to ever return to acting and required to never have her photo published. She later won a lawsuit overturning this, but that she was forced to go to court leads one to wonder why if not only due an ex-husband's cruelty. It was 1922 and that same year Buster Keaton made a film that openly parodied Hart, who some in the industry believed was "prone to domestic violence". Plus, Hart, without knowing or working with Fatty Arbuckle, had gone after Arbuckle in his troubles, publicly promoting his guilt. Keaton co-wrote, with Arbuckle, the script for "The Frozen North", produced, and directed it. The end has Keaton-as-Hart being shot by his wife in the back, then as he weakly raises himself on an elbow to take a shot at either the woman he had just tried to rape (or had actually raped), or her husband with whom he'd been fighting, he's roused in the theater by a janitor who tells him to wake up, the movie's over, and brandishing a newspaper as a gun he realizes he'd been dreaming.

It's a damn peculiar film for Keaton, and as a parody of Hart it's more than brutal. It's devastating in its rancor.

At work, Millie hopes to be courted by interns. At the apartment building, she hopes to be courted by the tenant male singles who congregate around the pool with other tenant women. At Dodge City, she hopes to be courted by the cops who hang out at the shooting range and bar--and Edgar, eager for customers, and adoring female attention, is a person who doesn't ignore her.

To introduce Pinky to Dodge City is to open up to her what is a rather sacred part of Millie's life, a place where she feels at home and accepted. Embarrassed by Pinky, rather than rejecting her new roommate outright, she tries to school her to behave with what Millie considers sophisticated decorum, even in this testosterone-fueled fantasy of the Wild West that was made by bad good guys and good bad guys. When Pinky sticks her head in a theatrical noose, Millie scolds that there are cops here, as if she must behave in a certain way for them, to gain their approval or to keep from attracting the wrong kind of attention, like a parent might threaten, but it also reveals Millie's relationship to the myths of the bad good guy/good bad guy deputy marshal that was Wyatt Earp, to these men who define law and order for her, who she imagines are her ultimate protectors. Whereas Pinky will be drawn to Willie, Millie ignores her much as she's been ignored, her focus always being on the men. A reason her fellow female workers resent her is because Millie passes them over in order to eat with the male interns. When Millie describes things she loves to Pinky--irises and romantic dinners--Pinky's expression falls and she becomes disinterested when Milly finishes by orienting these pleasures to being ways to capture a man. Pinky's resistance to Millie's focus on men highlights how much of Millie's life is ruled by men, how she shapes her identity around them, even while she admits that if she ever marries it's the man who is going to have to move into her world.

Instead of a man moving into Millie's apartment, it's Pinky. The night that everything falls apart and Millie humiliates Pinky, telling her no one wants to be around her and to move out if she's going to judge how Millie lives, we associate with Edgar Hart, because Pinky pleads for Willie, for Millie to not go to bed with Edgar because of Willie's pregnancy. But it is also, perhaps even more saliently, the night of the day Pinky finally met Millie's former roommate, who doesn't look much like Millie but resembles her just enough, with her brown somewhat bouffant hair with its flip of a curl at the ends, and her straight cut helmet of bangs. She can be recognized as Millie's double, the woman she'd like to be. With this reveal, we are left to wonder what Millie might have been like before she met her former roommate, and how much of herself was modeled on this woman who wears Millie's colors, who has the brunette flip with bangs, and who hangs with men who like to party at Dodge City.

We are intended to wonder about this, Millie's relationship with her roommate who had Millie pushed out of the bedroom and sleeping much of the time on the roll-away bed, just as Pinky will completely take over the bedroom after surviving her dive into the pool.

Though Millie ignores Willie's paintings, they are what Pinky responds to at Dodge City. She is wholly absorbed by them. Millie doesn't take her to the apartment for the first time until after an outing at Dodge City, and so Pinky is astonished to recognize in the apartment's pool the same art. Millie tells her that was a painting that Willie had done years before. However, while Pinky sleeps, we have a scene of Willie painting the pool, as if this is occurring in the present, but it is also a scene separated from us by the same dreamy fluidity with which the film opens. Altman creates some intentional ambiguity for later we see Willie step down into the pool and retrieve what she treats like a paintbrush, shaking it off.

When Millie wakes Pinky to have her leave the bedroom for the sofa-bed Millie has already set up for her, Pinky reminds of a powerless child moved about by circumstances engineered by adults, When she realizes Millie's going to bed with Edgar, she's beyond troubled, and Edgar makes even more problematic the scene by the way he infantilizes Pinky. "Pinky baby," he calls her, asking if they have thrown her out of her "beddie-bye"", then suggests she join them. "Two is fun" but three, he imagines, would be superlative. Later, when Pinky's parents come to see her, Millie gives up her bedroom to them. When she attempts to sneak in late at night, to get something she needs, presuming them to be asleep, she instead is stopped cold when she finds the couple twined together, having sex. It's disturbing because Pinky's father is so little present when awake, though he is aware and occasionally inquires what's going on. There's something about it all that reminds of Goya's "Saturn" devouring youth. When Pinky dives into the pool, she interrupts Millie's having sex with Edgar, perhaps even prevents it from happening, and now here is Millie, who pines to be sexually attractive and active, shocked by the elder couple having sex when to her they should be too old, whereas she is alone. The viewer may stop there, but we need to connect this back to Millie and Edgar pushing Pinky out of the same bedroom, and Edgar beckoning Pinky to join them. In the dreamy language of the film, these two events are connected, and one can begin to get a sense of how the unit formed by Pinky's parents might be so profound in its insularity that she was scarcely recognized as an individual.

More disturbingly, considering the dream language of the film, how these events are tied together--Pinky's disinterest in men, and her horror at Dodge City's crone head of Gertie that spits mockingly at her, which is later overlaid with the face of her mother in the dream she has--one may wonder at what kind of abuse she might have suffered above and beyond alienation. Her mother's only other story about this child is that Pinky was prone to falling, such as one night when leaping on her bed she fell into a wall and required stitches. In the film, that event is connected with Pinky who, in a profoundly disoriented state, transfixed by the pool, climbs the balcony, and "falls" in. What is she reliving?

As Pinky stands on the second floor rail overlooking the pool, at first she seems to fixate on the raging figure of the male character painted in the pool, raising her arms in a manner seemingly similar to his.

However, she then focuses on the pregnant belly of one of the three women who always accompany the man.

Altman then shifts the camera to the surface of the pool, made dark, so it reflects Pinky as she plunges into it.

Is she committing suicide? At least sacrificing her character as Pinky? It seems on one level she is diving into Willie's art, the world she is depicting. She enters the water and is thus born into what she couldn't fully comprehend consciously.

Appropriately, it is Willie who hears and saves Pinky, as if she is hyper-connected with the world of her painting in the pool and so immediately responds when Pinky dives into it. Heavy in her pregnancy, she enters to rescue her, calling out for help. She stands shivering in the water, stunned, as Pinky is pulled out and tended. Later, when Willie's child is stillborn, cold, we might think back to this night and wonder if there is a connection if only in the dream language of the movie.

What marks the difference between this pool painting and the others in the film is that the three women figures are banded together in the forefront while the man, who aggressively overwhelms in the pool painting at Dodge City, is smaller here, in the upper left background, still raging but it's as though he's being distanced, even driven away. When Willie is giving birth, Edgar protests she doesn't need him there. These three women, Willie, Millie, and Pinky, have constellated as a group through the relationship of each to Edgar, and, as depicted by Robert Altman, they will end in forming their own family.

Pinky is already imitating Millie before her suicide attempt, but without becoming like her. She's an acolyte, a fan, who first goes so far as to take Millie's first name as her own, Mildred, saying Pinky is just her nickname, but we later learn from her mother that her father had named her Pinky. She wears Millie's clothing without permission. She reads her diary. Then she supplies Millie's social security number as her own at work, which makes no sense for of course this was going to be discovered. Using Millie's social security number shows she's no con artist. One has to wonder if Pinky herself does not have a social security card and doesn't know exactly how they work. Eventually absorbed into Millie--or so it seems--becoming the woman that Millie would like to be rather than Millie herself, perhaps more like her first roommate, Diedre, in the way she attracts male interest, she is almost parasitic. Having taken over Millie's apartment and life, leaving it in shambles, she then deliberates on how to oust Millie. But had she planned this from the beginning, or is it Pinky seriously being ill, as Millie insists, and having moved into this twin personality?

In the film, Pinky has a fascination with doubles that is explored from her first day at the rehabilitation center. When she meets a woman who seems later to show no knowledge of her, Pinky is confused, then learns that twins are employed at the facility. She even discusses this with Millie, pondering if the twins switch places, or if they can even tell themselves apart, a topic that unsettles Millie so that she asks to change the subject. Millie, though she models herself on magazines, prizes her sense of individuality, and when she hears Pinky tell Edgar that her real name is Mildred, that Pinky is only a nickname, is at first taken aback then frustrated and displeased that her roommate shares a name that she apparently dislikes.

This is, however, called 3 Women. When Pinky follows the twins, she is a third, imitating, but she soon wearies of that game, breaks the imitative stride with a skip, and quits her pursuit.

Complementing this, Altman immediately after shows Millie following two of her fellow workers who have formed their own sort of twinship--though they disdain the twins for caring only about themselves and seem near as disinterested in others. Millie, like Pinky, is the excluded third.

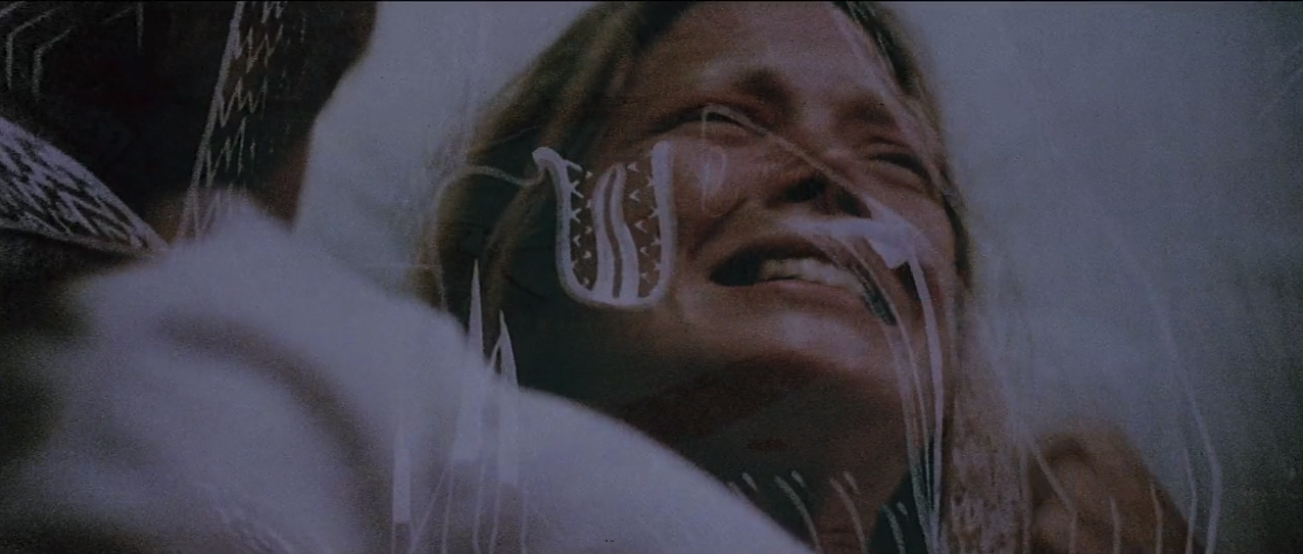

When Pinky lies comatose in the hospital after her perhaps attempted suicide, having struck her head on the bottom of the pool, Altman shows Willie alongside her doubled reflection as she gazes in Pinky's room. Though Willie doesn't know the young woman, she appears torn apart, and of course this would be from her having saved her. An intense personal connection has been forged, and this was a person who had complimented her on her art, drawn to it.

Altman shows Millie as well alongside her doubled reflection. What no one knows, save Edgar, is how she must feel responsible, Pinky having been found in the pool almost immediately after Millie told her to get out of her life if she didn't like how she was living. The irony of Pinky's action is that the manner in which she gets out of Millie's life plants her more deeply into it and alters Millie's behaviors. Her affair with Edgar is over.

Yes, becoming Mildred, Pinky starts her own affair with Edgar, but it's to be noted she has taken the name Mildred, rather than Millie, which Pinky has said she hates. Even if Pinky had only said she hated the name in order to originally make herself closer to Millie, to cause Millie to feel they had a deep connection, it remains associated with a banished identity, an original self that Millie shunned with the adoption of a nickname.

People tend to say that Pinky becomes Millie but, as I've pointed out, that's not the case. Pinky gives up wearing Millie's clothing, showing her own new style. She parties and exhibits no interest in taking up her share of the responsibility for the apartment when she's well enough. She does not behave like the responsible Millie.

Altman's film was based on a dream he'd had on identity theft, to which there was no plot, only these two actresses involved, but he also admits Bergman's Persona as an influence. There are things in common between these films, but they are also very different in the treatment of the subject of an unhealthy relationship, Bergman's film presenting certain mysteries (the reality vs poetic expression) that aren't part of the package with Altman. Altman's film has its own mysteries, and 3 Women has a very American 1970s flavor as its bedrock which is as critical to the film as the relationship between the women. Bergman's dark and brooding film mostly takes place in an isolated setting, whereas community/social context is essential to 3 Women, and for this reason alone they couldn't be more different. To me, there isn't a single misstep in Persona, while the end of Altman's 3 Women can seem a little clumsy, as if Altman wasn't confident how to wrap up the catastrophe of Millie rushing to help Willie and becoming midwife to a stillborn child. Being a writer and artist, when I make an analysis of a film, I try to accept it on the director's terms, looking for why a director felt something that might seem out-of-sorts to me was considered essential, why it had to be this way. Persona presents no such problems, whereas the ending of Altman's film does.

3 Women and Persona are movies I first viewed on the big screen. I saw 3 Women when it came out in 1977 and have always loved it and counted it as a film with impact though it was scarcely noticed at the time. Persona I would have seen no later than about 1978 or 1979. So, as things happened, I saw 3 Women before Persona, and thus I didn't link the two as Persona wasn't yet in my lexicon.

How alike are the two films?

Persona concerns an actress who suffers from, one coud say, an existential crisis, falling silent on stage one night during a production of Electra, recovering for the remainder of the play, but the next day taking to her bed and refusing to talk. She rejects even her husband and young son and is hospitalized. Her doctor has recognized this as a decision rather than mental illness when, after several months, she is paired with a young nurse, Alma, twenty-five years of age, who will act as her companion. Alma already admits she might not be an appropriate caretaker, that the actress, Elizabeth, may be too strong for her psychically, that she doesn't have enough life experience. As Elizabeth's residence in the hospital will useless, believing that she will eventually simply tire of her silence, the doctor sends them to live together in restful isolation on the coast. It starts out well enough, and though Elizabeth doesn't talk she does become a participant, doing things with Alma, even writing letters, which is on the way to finding her voice again. As things progress and Alma becomes more comfortable with the silent Elizabeth, she begins to disclose things to her that reveal her as confused by her openness to being impulsively influenced by others. One day, tipsy, she tells her of a sexual experience she had with a man other than her boyfriend, taking encouragement from another woman with whom she'd been sunbathing on a beach. The two had only just met, and when the woman had sex with two strangers who had approached them, Alma readily behaved in a like manner, excited by the situation, not out of a feeling of enforced compulsion. She became pregnant and had an abortion. Alma also tells Elizabeth she imagines that they look like, that she is even like her, and as Elizabeth is an actress she'd have no trouble becoming her. She imagines she hears Elizabeth speaking to her, rather like a mother, telling her to go to bed before she drunkenly falls asleep at the table. That night it seems that Elizabeth might have even gone to Alma's room where they stood and held one another, but Elizabeth, when questioned, denies either of these things happened. She did not speak. She did not go to Alma's room. Elizabeth discloses in a letter to her doctor that Alma is fond of her and divulges secrets to her, relaying Alma's story about the abortion, and that she is an interesting study. Alma, secretly reading the letter, already disequilibreated by her vulnerable disclosures, her deep sense of intimacy with Elizabeth, crumbles and becomes hostile. She responds by injuring Elizabeth intentionally by leaving on the ground a shard from a glass she'd dropped so that Elizabeth will step on it. She scolds that she's learning from Elizabeth that artists aren't more compassionate than others and divulges she'd read the letter. They have an altercation that turns into a physical fight when Alma grabs Elizabeth and starts shaking her, trying to force her to speak. Alma is so out of control as to grab a pot of boiling water and almost throw it at Elizabeth. She stops just in time when Elizabeth screams, but she prides herself on having made Elizabeth feel a fear of death. Afterward, she begs Elizabeth's forgiveness for that and other cruelties, excusing her behavior on Elizabeth having cajoled her into talking and it feeling so good to reveal herself, only to be injured when she felt used. That night, Elizabeth examines the WWII photo of a young boy holding his hands in the air, terrified, a gun held on him, taken prisoner by Nazis. After this, the level of enmeshment becomes so impossible as to be dream-like with Elizabeth's husband appearing to visit, confusing Alma for his wife, and Alma accepting the role and becoming involved with him. Then Alma says she will reveal the truth to Elizabeth about herself--that Elizabeth never really wanted to be a mother and hoped that her child would be stillborn, for which reason she has virtually abandoned her son, feeling nothing for him but disgust and her own shame of the child loving her and she not loving in return, giving him up to others to raise so she can return to the theater. With this story, Alma now protests she's not like Elizabeth at all, that she doesn't feel like her, but the cruelties continue with Alma clawing open a vein of her arm and Elizabeth appearing to drink from it, after which Alma so physically and relentlessly beats her that in the following scene Elizabeth is again in the hospital, completely unresponsive, which is what Alma wants, for her to be speechless except to repeat the one word she demands she speaks, "Nothing". Elizabeth has been battered into true, mute obedience, incapable of betraying a secret, only a body lying in a bed. Alma had made the silent Elizabeth into her confessional mirror of sorts, lulled by her silence, knowing very little about her as a person, and it is a mirror that she is bound to hate and want to destroy. At this point, Alma wakes from what we realize is a dream. If we examine what came before, we realize the last action before the dream was the evening after Alma begged to be forgiven, the night Elizabeth sat and examined the photo of the young boy in the Warsaw Ghetto. The film ends with both packing, preparing to leave the island. They behave as if nothing has happened except that they are not friendly with one another. The film is finished. They part.

Bergman has said that the Liv Ullman character, Elizabeth, was experiencing a crisis of truth, how does one stay true to one's self in the daily business of relationships, speaking, interacting, and is it essential? He had considered this in his own life, experiencing his own crisis of truth, and decided a way to escape this would be to be silent, but then realized that too becomes a mask. This idea of the crisis of truth is divulged in the film itself, but by Elizabeth's doctor, and in context of the film we have no idea if she is forcing this reading upon the situation or not, but Bergman makes it clear this is Elizabeth's motivation.

Elizabeth and Alma are not Millie and Pinky, but there are likenesses. Millie does take on a maternal role, even that of a nurse, but it's Pinky who is like Alma and takes over Millie's life. What begins with a kind of idol worship, on both the parts of Alma and Pinky, becomes cruel and controlling as they attempt to possess the identities of the idols who they also seek to destroy, feeling rejected by these women who've disappointed them. What I'm almost more interested in ends up concerning the child in both films. Alma accuses Elizabeth of having wanted a stillborn child, and Willie's child is stillborn, there is that similarity. One could also consider Millie and Pinky most resemble Persona in Millie having been abandoned by her parents, then Pinky also adopting that role, as Mildred, and wanting to find out who she is. In this way, they are the child in Alma's tale of Elizabeth's son who instinctively loves his mother, for which she resents him.

Bergman leads the viewer to see Alma and Elizabeth as doubles by highlighting physical similarities, but though many look on Bergman as revealing the masks women wear and stripping them away, Liv Ullman has stated she believed the film was about Bergman, himself and his double. She has said she felt that, as Elizabeth, she was the Bergman who wanted to turn away from the world, and that, as Alma, Bibi was the part that wanted to understand and draw back in--but she allows that when the film was made neither she nor Bibi understood it. They were, however, fascinated, when Bergman merged their faces, making them look as one.

Bergman had relationships with many of his actresses, and had been in a relationship with Bibi Andersson, who played Alma, before becoming involved with Liv Ullmann, who played Elizabeth. In Persona, he explores with making them one woman, and his blending their faces makes this so for the viewer. Alma, in her dream, even accepts Elizabeth's husband as her own when he confuses her with Elizabeth. They also end in reacting forcefully against this, trying to individuate themselves in each their own way, but the viewer is left to believe there is something in women that makes them susceptible to a permeability that is erotic, maternal, and childlike.

Bergman had little use for the nine children he had with his wives and lovers. He self-admitted that he saw no reason to spend time with them until his final wife insisted on having summer get-togethers, which he found he enjoyed. Only three of those eight children, still surviving when he died, thought it was worth making the effort to attend his funeral.

I'm not faulting Bergman for using his life as a basis for this film. This is what artists do. They use their experiences and find commonalities that make them able to synthesize the experiences of others. They put themselves in the place of another and attempt to comprehend their perspective. This doesn't mean that their art is about themselves, but artists necessarily create through making resource of their own experience. But people watch Persona as a film about women, without realizing how Bergman is very much there, a part of this movie, despite the fact he directed it, despite the fact he wrote it during a stay in the hospital (perhaps thus Alma, the nurse, he would be well aware of the controlling nature sometimes found in medical professionals), and Altman, in a way, makes the mostly absent man of Persona a part of 3 Women through the character of Edgar, through the cops, through the male figure in the murals, and through a society that has molded these women so that Millie's aspirations have all to do with making herself pleasing to a man. The male, in Persona, is made less a character than a question mark by being expressed as the boy who tries to touch the faces of the film's women via the screen.

When did Alma's dream begin? The night Elizabeth opened a book she was reading to find stuck in its pages the photo of Nazis taking prisoners in the Warsaw Ghetto, a boy figuring most prominently. Bergman several times inserts reality into the fiction of Alma and Elizabeth, which is even treated sometimes as a film. Perhaps he does so to briefly break the fiction and reorient the viewer to real life catastrophe, the monstrous ways humans treat one another. Elizabeth is obviously puzzled to find the photo in her book. Either she had once slipped it between the pages and forgotten about it, or Alma has placed it there. After getting over her surprise, she studies the image.

Bergman was, as a teen, impressed by the Nazis, their speeches, feeling them charismatic, and attended a rally he found fun, then was shocked as Nazi atrocities were revealed and was reluctant at first to believe they happened. There's going to be some guilt there, and the boy that Elizabeth has willingly abandoned, refusing to see her family or communicate with them, becomes a primary subject of his film. However perceptively Bergman paints these two women through two brilliant actresses, they are also a portrait of himself, and the bewildered and rejected boy is a primary subject, trying to connect with and reach a distant mother. This is plainly portrayed in the film. A boy appears toward the beginning, lying on a bed in a hospital like setting that we first mistake for a mortuary, his image intercut with those of elderly people who appear to be dead but are instead asleep. A bell rings, waking up one of these individuals, and the boy stirs as well. He sits up, puts on his glasses and begins to read Var Tids Hjalte, Swedish for A Hero of Our Time by Mikhail Lermontov. He then approaches what to the viewer seems the lens of the camera, then we are behind the boy and see he is touching a film screen that keeps switching between the faces of Elizabeth and Alma. The film ends also with this action of the child striving to touch the face of the woman.

When Alma had first met Elizabeth she had examined a photo of Elizabeth's son that was included with a letter her husband had written her. When Alma had remarked on what a cute child he was, Elizabeth had taken the photo and torn it in half. Elizabeth later being confronted with and examining the photo of the boy in the Warsaw Ghetto, as her next action is to pack up and leave the beach house, one wonders if with the examination of the photo she had decided to return home. But recollect, it is after this photo we have what we later realize is Alma's dream sequence, or it could even be partly Elizabeth's dream. If we compare this photo with what Pinky sees and does before she dives into the pool, we realize that she looks at the figure of the man-beast in the pool's mural with his arms upraised, he looking more boyish than man in that art. She looks at the belly of the pregnant woman. She raises her arms in a gesture not unlike the man's, then plummets into the pool.

I wouldn't begin to suggest that Altman has drawn a connection between the upraised arms of the boy in the Warsaw Ghetto photo, and the upraised arms in this pool-side scene, if not for the fact that in Bergman's film the photo is the point where the dream begins, and in Altman's film Pinky's dive into the pool, her arms upraised, precedes also a sort of dream sequence with Pinky going into a coma and emerging from it as Mildred. For all intents and purposes, she doesn't "wake up" until the nightmare toward the end of the film, in which she sees moments from the past, things she didn't personally observe, as well as the future, including Millie's horror over having delivered the dead child. When she wakes up from the dream she tells Millie she's had a nightmare and asks if she can sleep with her. Edgar, letting himself in the apartment, mistakes what is going on for sexual and wants to join in, then reveals Willie is giving birth. Millie rushes with Pinky to help and tells Pinky to go get a doctor. But Pinky doesn't. She watches as the nightmare of her dream unfolds, already aware of what is going to transpire. Nothing she does could possibly make any difference in the outcome for Willie and her baby, so she stands there, transfixed.

Wikipedia notes:

Albert Camus' novel "The Fall" begins with an excerpt from Lermontov's foreword to "A Hero of Our Time"": "Some were dreadfully insulted, and quite seriously, to have held up as a model such an immoral character as A Hero of Our Time; others shrewdly noticed that the author had portrayed himself and his acquaintances. A Hero of Our Time, gentlemen, is in fact a portrait, but not of an individual; it is the aggregate of the vices of our whole generation in their fullest expression."

Whereas Bergman occasionally lifts the audience out of the fiction to remind them of the trauma of reality, the horrors of which people are capable, Altman instead, with the murals, repeatedly drops the audience into the world of myth. Altman doesn't draw a perfect correspondence between the boy-man in the pool's painting and Pinky's plunge into the pool, he doesn't even make them emotionally similar, but what he does is bookmark this scene so that it directs to the photo in Bergman's film. By the end of Persona, so much else has happened, so much cruelty, we will have forgotten the picture of the boy in the Warsaw Ghetto, even though Bergman returns to the child touching the blurred image of the woman's changing face on the screen. We haven't even begun to understand why the picture of the boy in the Warsaw Ghetto was shown, except perhaps to remind, in the midst of this fiction, of the very real, heartless cruelty of people, how they are empowered by making others fear. By the end of 3 Women one isn't likely thinking back to Pinky's dive into the pool, for on the surface we may feel we pretty well understand it.

Early in Bergman's film we see a person being seemingly nailed to a cross, a large nail hammered through their palm. I've thought the boy in the Warsaw Ghetto photo may be tied with the crucifixion, his arms upraised. Before watching Persona again, after many years, I had wondered if Pinky's raised arms might carry a hint of crucifixion.

I may seem to have wandered off course, dipping so deeply into Persona, lingering on the relationship of the alienated boy to the two women whose faces he attempts to reach--Elizabeth and Alma. This certainly isn't a detour I had seen myself taking before acquainting myself with Persona again after many years, and I have spent days wondering if it's best left out. But though Altman's is a film that is ostensibly about three women, just as Bergman's was about Elizabeth and Alma, the more one reflects upon the stories the more one sees how crucial is the child in both films. Bergman's Elizabeth has her husband reminding her, in the letter that accompanies the photo of their son, how she had once told him that the best way to consider marriage was the partnership of two anxious children ruled by powers "that we can only partially control." In Alma's dream, the husband speaks of this again, that they are both children, tormented, helpless, lonely children.

Before I began this analysis, I had watched the 1960 Hollywood version of Kerouac's The Subterraneans. I'm not a great fan of Kerouac because of the sexism but I appreciate some of his writing. The movie was worse than I imagined it would be. It's love lost in the book, Kerouac's girl leaving him (and he pushing her to leave him), while in the film, after George Peppard nearly ruins a relationship with Leslie Caron--and is lectured by his one-night stand that he will never really love anything except for his writing--he and the now pregnant Caron scrape together a happy we're-getting-married-now-and-will-be-a-family ending, rescuing one another from the dead end, Dionysian world of the Beats.

A surprise was to realize Janice Rule was playing the part of the "man-hater", Roxanne, who completely turned around after her one night stand with Peppard-Kerouac, purchased the first skirt she had worn in years, and decided to leave San Francisco and seek an un-Beat life elsewhere, like maybe on some farm. Her eyes had been always deeply rimmed with kohl, which she said was to keep away demons (according to some tribe) and she wiped all this off as well, having previously been scolded for it being a mask. An artist, she also rips apart and burns her paintings as part of preparing to leave this bad Beat life.

Janice again an artist in Altman's film, I was reminded that the character Willie has smokey eyes throughout, and that when identities shift at the end, Pinky now identified as Millie and Millie is simply the mother, Shelley takes on the smokey eyes. Note, too, how Shelley has lost her bangs so either she's had months to grow them out or we're not exactly where we think we are in the multiverses. There have been considerable changes made to the tavern, all the Wild West and dirt bike stuff removed outside, all the Wild West things removed inside, tables put in place for dining, and flowers, such as the yellow flowers we see on the jukebox now, which remind of Shelley's former existence as the woman who loved yellow.

In real life, The Subterraneans character, Roxanne, was based on the artist, Iris Brody (also sometimes spelled Iris Brodie), who leaped from a five story building in 1961 after having a child, the father abandoning them, and returning to live with her mother, with whom she had a profoundly dysfunctional relationship.

I had an eerie feeling. Like Janice's Roxanne had moved out to the desert, ended up with Edgar, and continued painting. As if Iris had rather come back to life after her five floor dive off a building in New York, and was being given an ending in which she might rest in peace. Contributing to this eeriness, perhaps a primary reason for it, is that, like Roxanne, Willie's eyes are darkly framed with eyeliner. We recognize this, but at the end of the film we are made aware that it is a fundamental identifier with her when Millie takes her place and now her eyes are darkly lined with eyeliner, as had been Willie's...as had been Roxanne's. This led me to wonder if there was something in Janie Rule's experience with her character in The Subterraneans that was imported from that film.

Iris Brodie was known, I read, as one of the "Three Graces", the other two being the artist/writer/muse Sheri Martinelli (alias Sheri Donatti), and Ruth Goldenberg

Along with the psychological and sociological levels of approaching the multiplicities of personas, there is also the mythic aspect, these women being caught up in something outside themselves, so fundamental that it functions as an archetype. Which is why Altman begins the film with Willie working on the maze mural, showing the maze first of all. Even if someone doesn't know about Knossos and the difference between labyrinths and mazes, they know the thing Willie is working on depicts a construction of halls and rooms in which one can easily become lost and unable to find their way out. The maze walls off the left of the painting, representing that if the figures are to escape the desert they must pass through the maze, which means they also live within it.

Pinky is at first excited when introduced to Dodge City, but is anxious around the guns. What she is drawn to is what Millie ignores--Willie and her art. The paintings are the one thing that command, from Pinky, a level of awe that demands respectful attention. When she tells Willie she likes her art, Willie stares then walks off as she seems to conceal a secret smile, and Millie reproves Pinky for being so embarrassing. But who has Pinky embarrassed and how? Willie appears to welcome at least a certain degree of isolation. She doesn't seek attention. She isn't shown communing with others. While she paints her murals, the men ride in endless circles on their dirt bikes in the background. She doesn't shoot on the range with them, as Millie does, but waits until she is alone to pepper with bullets the snake paintings with which she adorns the walls of the bar. Willie doesn't say anything in response to Pinky, and it may instead be Millie who's embarrassed as she has encouraged Pinky to pay no attention to Willie.

"Bodhi Wind" (Charles "Chip" Kuklis) painted the murals for 3 Women, assisted by Geary Holst who appears to have acted as an assistant for decades. There are three large murals in total--the one in the Dodge City pool that shows the maze with the three women and man, the Dodge City patio maze that shows the same group excitedly reacting to a spiral in the sky, and then the pool mural at the Purple Sage Apartments. Millie happens to have a fish tank in her bedroom window that is filled with water but has no fish in it, and sometimes we are positioned so we see outside the window, the pool, through the water in the tank, and this tells us something about the film. We never see Millie herself interact with the aquarium that's set on the desk where she has her Social Security card and address card kept under a protective glass surface. Pinky however does once view Willie, down by the pool, through the water of the aquarium, and her dream/nightmare seems connected with the aquarium.

Though interest in Bodhi Wind has been niche, there's enough that it's confusing so little is known about an individual who people speak of as having been very personable, if complicated, and perhaps was able to live as an artist all his life.

He was born 9 Oct 1950, Charles A. Kuklis, in Pennsylvania, and died 27 November 1991 in Marin County, California. His burial is recorded on Find-a-grave and gives no indication of the "who" of him in the Find-a-grave description. His gravemarker gives his nickname as "Chip", with no mention of Bodhi Wind. His obituary in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette simply reads, "Suddenly, on Nov. 27, 1991, at San Rafael, CA, Charles A. (Chip); beloved son of John and Jean Kuklis....", provides the names of a few other family members and gives the time and place of the service.

Altman says in his commentary on 3 Women that Bodhi Wind stepped off a curb in England and was hit by a vehicle, and that he didn't know him well. A 2013 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette article states he was "struck and killed while walking along a Los Angeles freeway". On 29 Nov 1991 the San Francisco Examiner reported Bodhi Wind had been identified as an individual who was waiting for a bus, on U.S. Highway 101 at the Golden Gate Transit bus stop near the North San Pedro Road exit, when he was killed by a hit-and-run accident.

An artist can work in multiple styles, and of course their art will likely change throughout their life, but when I look at what there is of Bodhi Wind's other art, what has been preserved on the internet, I wonder at the exact creative process concerning the murals for 3 Women, and am fairly certain that though Altman chose Bodhi Wind because of his style, Altman had the plan. One article from the time of the film gives the impression the murals were conceptually a communal product and that Altman had Bodhi Wind tone down his style. The creatures in the murals are described most often as reptilian, but they are more simian, with reptilian embellishments, and Bodhi Wind gave himself as greatly influenced by Navajo art, especially with the coloring. Even though, when I first saw the film the year it came out, I didn't know anything about the artist who had done the murals, there was something about the depiction of masculine and feminine that strongly communicated to me these were painted by a man, and while I was able to overlook this it still itched that Willie was painting murals done by a man. That may sound petty. That may sound like I think art can be recognized and categorized by sex or gender. I swear that's not it. There was however something about the musculature that made me feel it was a male interpretation, not that of Willie's. I grew used to and eventually accepted the art as being Willie's, so that now I would have a difficult time imagining the murals as being anything other than what they are--and yet I remain conscious that it's not a woman who was the artist. I suppose I remain conscious of this as it seems so important that the murals in the film be the expressions of a woman.

It took me far too long to make a connection between these murals with the blue monkey frescoes of Akrotiri on the Aegean island of Thera (Santorini), circa 17th century BCE, part of the Minoan civilization with which is associated the labyrinth. In this fresco below, the monkeys, given as chased by dogs (I see no dogs), climb rocks in an attempt to escape them. In Minoan art, I read that the monkeys sometimes accompany priests.

Uploaded by Mark Cartwright, published on 24 March 2014. The copyright holder has published this content under the following license: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike.

Another brief side trip, I also realized that a screen painting I had done back in the 1980s, which I'd based on Minoan art, was of one of these blue monkeys that had been mistakenly "restored" as a blue boy. Back when I had worked on the painting, he had been given in the description as a blue boy saffron collector, but it's since been revealed that the restorer had completely reimagined the face as human, ignoring the remnants of the simian tail in the fresco. I mention this because I remember my perplexity, when I was working on the mural, not doing an exact copy but a reconfiguration, how perplexed I had been by the body when I was painting it. I felt like this was human but not, and so I was confused. I knew, painting it, which gives one a different familiarity, that this wasn't a body built to walk upright 100 percent of the time, that there was something off about it. It felt like the original painter had been somehow confused about the lower limbs, and emphasized the upper. And it was wrong. It wasn't right. So, that's what I had recognized, that the restorer had misinterpreted the figure as human when instead it was a monkey. It was the same way I felt about the murals in the pool, the wrongness in the way that they were painted that didn't feel like they came from Willie's hand.

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike.

We can see the influence of the Minoan simian bodies and faces on the "creatures" in the 3 Women murals who seem like mystic communications of an embedded, ancient, psychic space rather than any alternative and alien landscape. That they are very prominently accompanied by a maze in the first mural we see confirms the connection for me, and the last we see of the murals, after Edgar's death, Shelley is out washing down the mural that has the circular labyrinth style image of the sun or moon.

The heavily pregnant woman is in each of the three murals, so when Millie says that Willie had painted the one in the pool a long time before then either she was mistaken or Willie had been painting the pregnant woman prior her pregnancy. The most masculine aggressive of the three is the one that includes the maze. The woman seems to be at her most pregnant here and perhaps she has begun to give birth, bending back, supported by one of the other women. The first time Pinky sees Willie she is working on the maze showing the spiral in the sky. The way the creatures react to the spiral in the sky, they seem to view it as a sign, something different that has excited their attention. In the mural at the apartments the two non-pregnant women appear to grasp one another, the pregnant woman a little behind them, while in the distance the man either is walking away or simply separated from them.

The figures are all feral, defensive, scowling, fierce, raging. Even if they weren't they couldn't help but appear to be with their fangs and sharp, long talons on hands and feet. They give the impression of belonging to a cruel world, a harsh world, one in which they have evolved as they are in order to survive.

On a whim, trying a search engine other than Google to see if I could find more on Bodhi, though I was done with this section, I came across this piece of art on eBay that is purported to be a first draft sketch for the murals for 3 Women.

This looks a bit more like a few other things I've seen of Bodhi's, and are evidence of a major shift in direction between Bodhi's initial concept and the later Minoan influenced work. The aggressive aspects are gone here. The women are less physically like the men, and all are simply highly stylized humans rather than being part ape, part reptile. The style leans toward the late 19th-early 20th century style of the fantasies of Kay Nielsen. One can see that what later became reptilian and snake-like started off more like body painting resembling the ripples of the sands on which the figures rest. They are romantic pairs of three women and men resting beside a pool in an Arizona-like landscape. Due their coloring, one could imagine the women as being creatures that emerged from the sand, the men as arising from the waters of the pool. Perhaps the ripples on their flesh is intended to remind of the dreamy quality of a mirage. No gnashings of piranha-like teeth, no claws, no monkey tails, the torso musculature is not radically emphasized. These pairs range from playful to reflective, the overall aspect being peaceful. Had these characters been given the same text, the same story, as the other murals, however with modifications to express aggression and tension and a simian-reptilian nature, I wouldn't have questioned the gender/sex of who had done this piece, accepting it as done by Willie. So...one has to wonder how much Altman had a hand in not just the story aspects of the art, but the design of what would become the nearly alien creatures.

I also found the below detail from some Bodhi Wind art that originally was on eBay but there is no page for it left. This was perhaps art that he later did based on his original idea for 3 Women? They are the same horses, the same people, more hyper-stylized, and saturated with color.

We can see much the same in a couple of details of Bodhi's art works on the Rutheh.com blog.

Looking further I find this album art by Bodhi Wind for Les Dudek's "Ghost Town Parade". by Bodhi Wind. The album's release date was 1978 but a 1978 Catalog of Copyright Entries seems to indicate the design was from 1972. It reads: "Dudek ; [cover ill. Bodhi Wind ; design 1972; PUB 10ec72; REG 14Jun78."

There is a hint of maze-work in this painting, between the natural landscape and the city, though it isn't the literal maze as in 3 Women.

Bodhi Wind was also the illustrator for Sun Ra's 1972 release of Fate in a Pleasant Mood, Sun Ra's 1975 release of Pathways to Unknown Worlds, and Pharoah Sanders' 1974 release of Elevation.

The distance between initial concept and final stage can be great, but the difference between the first draft art and the murals in 3 Women is rather astonishing, not only in physical style but emotionally. The impact of what the 3 Women murals became is dramatic, because they are so alien and primal. Maybe they were painted just as they should have been. Maybe I am only used to them now. I have no idea.

The fact the film focuses on three women rather than two, and that at the end of the film we have Pinky reverting to the child, who identifies her "mother" as Millie, and then we interpret Willie as the grandmother (her hair has gone partly gray), aligns them with the Triple Goddess that embodies the virgin, the mother, and the crone, and Altman confirms this in his commentary without describing them as the Triple Goddess. He states Sissy is the child, Shelley has taken Willie's place in becoming the mother, and Willie is like a grandmother. This is where Altman takes us in the end, though it's a little confused. Though the film is named 3 Women, Altman has kept us occupied with doubles, through Pinky's "identify theft", through focusing on the women who appear to naturally gravitate to a relationship of two, through the twins, and when the third was shown (as in the double reflections opposite the source of the reflection) it seemed more that the pairs were manifestations and parts of the one. Then at the end we are faced with the child, mother and crone. Unless he's showing how each aspect cut off from the other is incomplete (for each of these women is incomplete at the end) then it doesn't work for me, but the rest of the film is brilliant so I let it be as it is.

Though the film discloses that Edgar had an accident with his gun, in the commentary Altman ponders what happened to him and imagines he is probably hidden under a hill of tires out front of the house behind the tavern, in which we understand Pinky, Millie and Willie now live together. Which to me suggests that Altman was himself conflicted on the ending, had several ideas, and the one that personally was strongest for him was Edgar having simply disappeared. He says he doesn't want to discuss it too much, that he feels these things should remain mysteries that are "felt", but submits it seems Edgar has been pushed off the rock by the three women. As I mentioned earlier, the tavern and its environment have been also pretty well cleansed of Edgar's influence. Even the big Welcome to Dodge City sign at the entrance is gone.

Gone also are Shelley's bangs, as I've mentioned before, which is a mystery.

From the nightmare to not exactly the sublime. Though Edgar and the dirt bikers and the gun shooters are history, Shelley doesn't look very happy and Sissy is simply complacent. The only vaguely contented one appears to be Willie though she is now submissive to Shelley, as if her days of activity are done as she settles into cronehood. As I noted earlier, these women are each incomplete at this stage. Often enough a film brings a fulfilling resolution, and that means fulfillment for the characters. Despite the women having gotten rid of Edgar, this isn't a satisfactory resolution for them at all. But one feels that this part isn't real. That it is instead a kind of parable.

Willie says that she had a beautiful dream that she can't remember, which ties us back to the dreamy beginning.

I was wondering what could that beautiful dream be and was drawn back to a scene in Pinky's nightmare. Pinky's lying on the floor, covered in shrimp cocktail that appears to be blood, looking like a knife has been plunged in her chest. Altman says that were he to do it over again he'd leave out the nightmare scene, but I think it works, if only for this image, which needed some cushioning around it. Altman, in his commentary, relates a story about how some footage that didn't make it into the film was subsequent Pinky's making a mess with the shrimp, dumping it over her dress. When Millie goes out, Pinky lies on the floor with a knife tucked into her armpit like she's been stabbed, but when Millie returns she ignores this game. Part of this footage did actually make it into the film, but in the nightmare sequence, as if to communicate that Pinky felt like she'd been stabbed through the heart by Millie's attitude toward her that day. For Pinky, this is real blood, she has been stabbed, and one might wonder about the accident being with the shrimp cocktail, if the shrimp might be alluding to Willie's baby, the foetus. It's when Millie returns that she finds out the party she had prepared for was cancelled and she leaves the apartment to go to Dodge City and have some fun. In the nightmare, as Pinky lies on the floor, the knife seemingly lodged in her heart, we have what appears to be a scene of the tavern from that night, couples dancing to music on the jukebox. We may see Millie, as well as Diedre, both dancing with men. The most prominent couple who are having fun, dancing cheek to cheek, are Willie and Edgar. Willie is smiling.The pair look in love. This section of the nightmare follows after a shot of Willie asleep in the dry pool at Dodge City, but a different shot than Millie she goes to the shooting range to look for Pinky who has "borrowed" her car and sees Willie sleeping in the pool. Millie was surprised, and it seems to me that scene was filmed for this nightmare sequence, so that we go from Willie sleeping in the pool to she and Edgar dancing in the tavern, as if we've entered her dream, She's not only smiling, Willie joyfully reaches up and gently cups Edgar's face in her hands. As they dance, the image of the stabbed Pinky appears and grows to fill the screen as Edgar twirls Willie and he spins about. Then cut to Millie at the shooting range. This is also a different perspective than when we saw her shooting the gun earlier in the film; Edgar isn't with her, and she fires at the camera, a white cloud of smoke emerging from the gun.

Willie sleeps in the pool.

Willie and Edgar dance.

Edgar spins Willie as the "stabbed" Pinky appears.

Edgar spins about with his arms raised.

Layered over Edgar, Millie begins to appear with the gun.

Millie shoots.

Pinky and Millie look out again over Willie working on a mural.

Pinky fires the gun on the shooting range, overlaid on the pool as it was when being painted.

Pinky, unconscious, overlaid on the pool as it was when being painted.