ROCK EAGLE, PUTNAM COUNTY, GEORGIA

PART ONE

Traveling east on I-20, a little over an hour away from the millions of souls that constitute the metropolis of Atlanta--which we rightfully pride as the "cradle of the Civil Rights Movement", home of Martin Luther King--an otherwise unassuming emerald green sign carries the vaguely tantalizing reward of "Rock Eagle" off exit 114 and highway 441. The sign doesn't tell you what "Rock Eagle" is, and the name may seem somehow out of place among other nearby destinations, like Madison (incorporated in 1809 and named for President James, a slave holder who had negotiated a treaty with the Creek Indians), Monticello (named after slave holder Thomas Jefferson's plantation), and Eatonton (honoring diplomat and "undercover agent", General William Eaton, who had fought against the Creek indians in Georgia, and was U.S. consul at Tunis, his far-flung exploits recalled in the opening stanza of the Marine's Hymn). The promise of Rock Eagle is alongside a marker for the "Antebellum Trail", the latter a call for tourists interested in viewing Georgia's plantation history that for too long was only romanticized as gracious, mannered, and noble. While one concerns white supremacy and fortunes built on the misery of enslaved Africans, both ultimately relate to white supremacy and white settlers and the government divesting indigenous Americans of their homes, forcing them on a long walk to reservations across the Mississippi River. What came before and happened alongside several centuries of early white colonization always seems to dissolve into a mysterious, veritable anti-history of not-much-here-nor-there indigenous peoples who inhabited maybe this-or-that place for an undetermined amount of time in the remote past, these peoples always seeming to abandon their homes, to be replaced by other indigenous peoples who wandered in from somewhere else, wherever, the only verifiable links between place and place and people and people being traces of trade and tattered remnants that hint at sharing of culture.

Rock Eagle is in Putnam County, Georgia. Look up Putnam County, Georgia, located center to center-north in the state, and the earliest history given on Wikipedia is the naming of it, in 1807, for Israel Putnam, a "hero of the French and Indian War and a general in the American Revolutionary War". If we go by Wikipedia, nothing In Putnam County apparently existed before Israel who perhaps never stepped foot in Georgia, born and dying in Connecticut, but the French and Indian War led to France ceding to Great Britain all its claims east of the Mississippi River, for which reason the veneration of Israel Putnam. Putnam County and other territory in western Georgia was a part of those French cessions, land that as far as Indians were concerned wasn't the property of Europeans, but Europeans were staking out their present and future territorial rights, taking their eventual rule for granted. As of 2020, the percentage of population that was Native American in Putnam was 0.15%, or 33 individuals. In the early 19th century, this area was on the edge of Creek territory, who are given as oblivious to what had come before them, which in the 16th and 17th centuries was the Oconee province (the Oconee River runs through Putnam), also known as the Muskogean speaking Ocute, or Altamaha or La Tama, which came out of the Mississippian culture of the 1100s, which emerged after the late, middle and early Woodlands cultures. An 1814 map shows Putnam Georgia separated from Middle Creek Indian Lands by Jasper County to the west. A map of 1748 shows the area populated by the Yamacraw, relatives of the Creek. A map of 1732 shows the Okojee Nation. Archaeologists will have this all sorted, with shifts and nudges and reappraisals as needed, but for the layperson Georgia is often not even a matter of what was before and after the 1838 Trail of Tears but what's seen from the modern road, urban skyscrapers, shopping centers, residential suburbs, struggling small towns, farmland and woods, and it's in this--a map in which ancient history is what happened at most one generation prior--that the so-called "Rock Eagle" is located, a bird effigy mound which may have been constructed 2000 years ago, during the Middle Woodlands Period. 2000 years ago in Europe is also near incomprehensible if one isn't standing on a Roman road. For Europeans who, for generations, made the center of their timeline the birth of the legendary Christ, that imaginary point would be in the proximity of the time of the construction of this mound. Maybe. Dates are uncertain. The area is said to have been inhabited for at least 12,000 to 14,000 years. In Europe, the last ice age was ending, and some hunter-gatherers were giving up their nomadic lifestyle for a new stone age in which they began to settle down and farm, domesticating grain. In the Americas, squash, so important as a three sisters plant, wouldn't be cultivated in Mexico until 10,000 years ago, and corn not until 8700 years ago. The Nile River valley wouldn't be inhabited until 6000 BCE. This kind of deep history is difficult to comprehend.

A map of the cultures that constituted the "Woodlands" Indians shows everything in the United States of America east of the Mississippi River, though before stars-and-stripes 1776 there was no USA. Typically, maps absurdly impose on and dissect the past with contemporary political boundaries.

As far as many are concerned, even amongst children raised in its school systems, the history of Georgia is nothing much more than at some point in time it appeared on a map before that dividing line in time called Gone with the Wind. On different maps, Georgia will be a different color and If the map they are looking at shows Georgia as green then its history was a green something. Not a "green space". Just green. If the map of Georgia is orange then Georgia was that orange situation. As for Indians, they existed in an alternate universe where and when Georgia was some big hunting ground and Indians kind of lived here and didn't and those who did live here were probably Cherokee because all southeastern Indians have been absorbed by the Cherokee, as far as the general public is concerned, by reason of the popularity of the Cherokee in white storytelling, and as they left behind New Echota in north Georgia, with their expulsion to the west, they are most readily comprehensible as a people that were in Georgia and composed a nation recognizable by Europeans. But, honestly, the history feels so unwieldy that it's difficult to pick up and carry and absorb as one is able. As with any subject, the more one learns, the more one realizes what one doesn't know, and there is considerable Indian history in Georgia (and elsewhere) that is so little known that its remains are near invisible. We are the crust dwellers atop not simply lost worlds but worlds intentionally buried so that European occupation of "New World" wilderness would seem a predestined certainty.

I've spoken with more than several people acquainted with the interstates of America who say that I-20 between Atlanta and Augusta, Georgia is perhaps the most boring stretch of road ever. One breaks it into sections of landmarks achieved. Heading east, after Covington, the easternmost limit of metropolitan Atlanta, there is Rock Eagle, then the manmade Lake Oconee is always disappointingly not quite half-way through the 145 approximate miles, and finally, about thirty minutes outside of Augusta, there are the two exits to Thomson (not Thompson), Georgia, one of which promises the Laurel and Hardy Museum of Harlem, Georgia, and whenever I think "Harlem" I always imagine first Harlem, New York, because that's how the mind works. No matter the dozens of times I've passed the Harlem, Georgia exit, the initial association for me is the African-American cultural center of Harlem, New York, and basketball, not even the Dutch Haarlem, capital of North Holland, after which it is named. But first I always wonder, "How did that ever happen? How did a museum devoted to Laurel and Hardy decide to materialize in Harlem?"

There were well-traversed Indian trails here, touted as "famous", but about which one rarely to never hears. Highway 16, the "historic Piedmont scenic byway" runs, in Putnam and Hancock counties, alongside what was the Okfuskee Trail that connected Charleston, South Carolina to the Mississippi River and are given as having been used by the Creek, Cherokee, Chahta, Seminole, and white settlers. Six historic loops are promised, one of which will take one by the "Shoulderbone Mounds" site, between and above Eatonton and Sparta, but far off the beaten path, one seems to just pass in the maybe general vicinity of what was in the 18th century better known than the Ocmulgee mounds and recognized as having been once the home of a major settlement and Indian fort with a conical pyramid. As for the three-story Dyar Mound, now understood as used ceremonially up to the 18th century, there's no exploring it and its environs as the creation of the Lake Oconee reservoir submerged it in 1975. Rock Eagle is above Highway 16, while its sister site, Rock Hawk, greatly disturbed and not reconstructed, is just off Highway 16. Scenicbyway dot org says Rock Eagle and Rock Hawk are 5000 years old, seemingly going by a number once thought to be correct and who knows maybe one day it will become correct again. It's just been proven one mount on the Louisiana State University campus is 11,000 years old and another is about 7500.

How many tourists visit Rock Eagle a year, I don't know, but it can't be very many, not the kind of tourism one gets out west at old Indian sites, and to my knowledge none of the truck stops/gas stations/eateries at I-20 and 441 yet capitalize on or promote it.There are no "I've been to Rock Eagle" bumper stickers, no "Rock Eagle" magnets, no fake turquoise pendants of "Rock Eagle", no granuals of white quartzite sold in cellophane packets as souvenirs. Situated on a 4-H conference/summer camp center, opened in 1955, and operated by the University of Georgia, the tower is unmanned, no one to sell slim books on Rock Eagle or the Woodlands culture responsible for this mound and Woodlands mounds in other areas, no wood racks with slips of paper advertising resorts, the Etowah mound complex to the north, the nearby Booth Western Art Museum, or the Ocmulgee mounds to the south. If Georgia was desert, at least one individual would have comprehended the necessity of planting the fun landmark of a giant concrete dinosaur or two along the roadside, pointing the way to a modern Creek or Cherokee Indian trading post opened by an enterprising family, with a good frybread recipe, who didn't mind leaving Oklahoma for the East that compelled them to walk nearly 600 miles away, away.

The impression given of colonial-contact Indians of Georgia has tended to be that they were themselves only itinerant newcomers, invaders who held no real historical claims, dissociated as they always were from earlier populations.

When I was a child, not long after we first moved to Georgia, my maternal grandfather, who was always a hair's breadth from a rage-induced stroking out over any imagined offense against the patriarchy, took my male siblings down into the crawl space beneath the suburban house where he'd left on the red clay surface a couple of arrowheads for them to find, which he'd purchased somewhere and attempted to pass off as real. My brothers were excited with the find. I immediately comprehended the farce and ruined the moment by asserting the arrowheads had been planted there. My grandfather, who had also taught my brothers chess but refused to teach me as I was a girl and hadn't the gray matter to understand, choked beet red, arguing the find was real, but I refused to budge as I thought the ruse was destructive. If I was a little embittered that I was always excluded because I wasn't a boy, that wasn't the reason I stood my ground. Instead, I thought it bizarre to create this pointless myth of a discovery, denying real history. Finally my grandfather argued the arrowheads could have been there, but that wasn't good enough for me. It was still erasure, a cover-up by means of a fairy tale find that was also an odd prank intended to secure a bond with grandchildren with whom he'd elected to have no contact previously, never fostering any communication with us, never visiting us in Washington State despite the fact he was raised in Chelan and still had family there. But then he cared nothing about real history and our family was all fake so in that way the ruse fit. Mine wasn't deep knowledge, but I had grown up learning about Indians in Washington State and on the nearby Yakima Reservation, and had recently become conscious of Indian history in the family, so the fairy tales seemed bad faith impertinence. I won't try to describe those emotions here, and what constellated them, why I would be offended. When my son was young I instead took him to places like Etowah, hoping to impress on him the reality of Indian presence. We have a short video of our exploring a building in New Echota, what was the capital of the Cherokee Nation in Georgia, in which I can be heard enthusing about history amongst reconstructed buildings. My son is paying no attention, joyously running about talking about all the ghosts that are there. "There's a ghost, I see a ghost," he declares while I try to focus him on facts.

PART TWO

It used to be said--and still is--that Rock Eagle was one of two bird effigy mounds east of the Mississippi. But there are other such bird effigy mounds (River Glen subdivision site on Cabin Creek Road north of Athens and Nicholson in Jackson county), which archaeologists used to discount as rock piles made by farmers clearing their fields. And I wonder if this is to be partly, or greatly, blamed on white settlers anxiously wanting any claims exerted by Indian history to disappear so that white civilization could progress unchecked, archaeologists having absorbed these same tendencies to discount and deny.

The city of Cahokia is one of many large earthen mound complexes that dot the landscapes of the Ohio and Mississippi River Valleys and across the Southeast. Despite the preponderance of archaeological evidence that these mound complexes were the work of sophisticated Native American civilizations, this rich history was obscured by the Myth of the Mound Builders, a narrative that arose ostensibly to explain the existence of the mounds. Examining both the history of Cahokia and the historic myths that were created to explain it reveals the troubling role that early archaeologists played in diminishing, or even eradicating, the achievements of pre-Columbian civilizations on the North American continent, just as the U.S. government was expanding westward by taking control of Native American lands...

... landscapes and the mounds built upon them quickly became places of fantasy, where speculation as to their origins rose from the grassy prairies and vast floodplains, just like the mounds themselves. According to Gordon Sayre (The Mound Builders and the Imagination of American Antiquity in Jefferson, Bartram, and Chateaubriand), the tales of the origins of the mounds were often based in a “fascination with antiquity and architecture,” as “ruins of a distant past,” or as “natural” manifestations of the landscape.

When William Bartram and others recorded local Native American narratives of the mounds, they seemingly corroborated these mythical origins of the mounds. According to Bartram’s early journals (Travels, originally published in 1791) the Creek and the Cherokee who lived around mounds attributed their construction to “the ancients, many ages prior to their arrival and possessing of this country.” Bartram’s account of Creek and Cherokee histories led to the view that these Native Americans were colonizers, just like Euro-Americans. This served as one more way to justify the removal of Native Americans from their ancestral lands: If Native Americans were early colonizers, too, the logic went, then white Americans had just as much right to the land as indigenous peoples.

The creation of the Myth of the Mounds parallels early American expansionist practices like the state-sanctioned removal of Native peoples from their ancestral lands to make way for the movement of “new” Americans into the Western “frontier.” Part of this forced removal included the erasure of Native American ties to their cultural landscapes.

Source: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/white-settlers-buried-truth-about-midwests-mysterious-mound-cities-180968246/

When I saw how "Rock Eagle" and "Rock Hawk" were laid out in respect of one another, I had wondered if there was at least a third mound somewhere in the vicinity, another bird that would be part of the conversation.

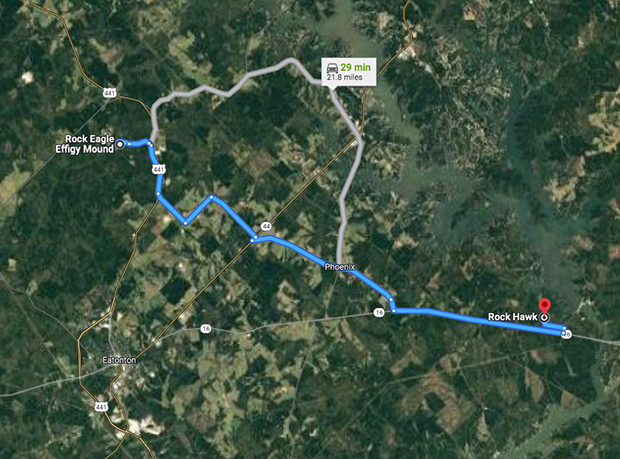

Traveling through Phoenix, Rock Hawk is 19 miles from Rock Eagle.

The beak of "Rock Eagle" is often said to point to the east, when instead it points southeast, the bird itself flying east/northeast. The observation tower can be seen at the bird's tail, screen left.

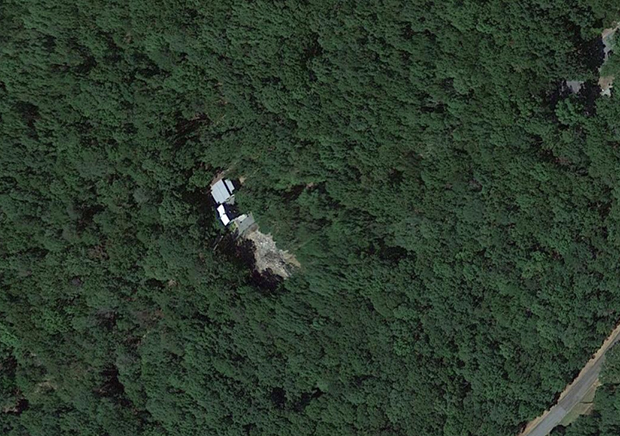

Google maps shows Rock Hawk's effigy is pointed southeast, its beak directed to the northeast. The observation tower is to the screen left at the bird's tail.

The below image is from a Google maps capture, and shows a barely distinguishable bird.

The presence of a nearby third effigy was discussed in 1936 when Rock Eagle was being excavated.

In 1805 Robert White acquired the property where the Rock Hawk Effigy is located through a land lottery but sold it in 1818 to Kinchen Little, who would become one of Putnam County’s most prominent citizens. (Rock Hawk was often known as the “Sparta Road Eagle” or “Little Eagle,” which generally referred to the Little family, but many interpreted this to mean an eagle smaller than Rock Eagle.)

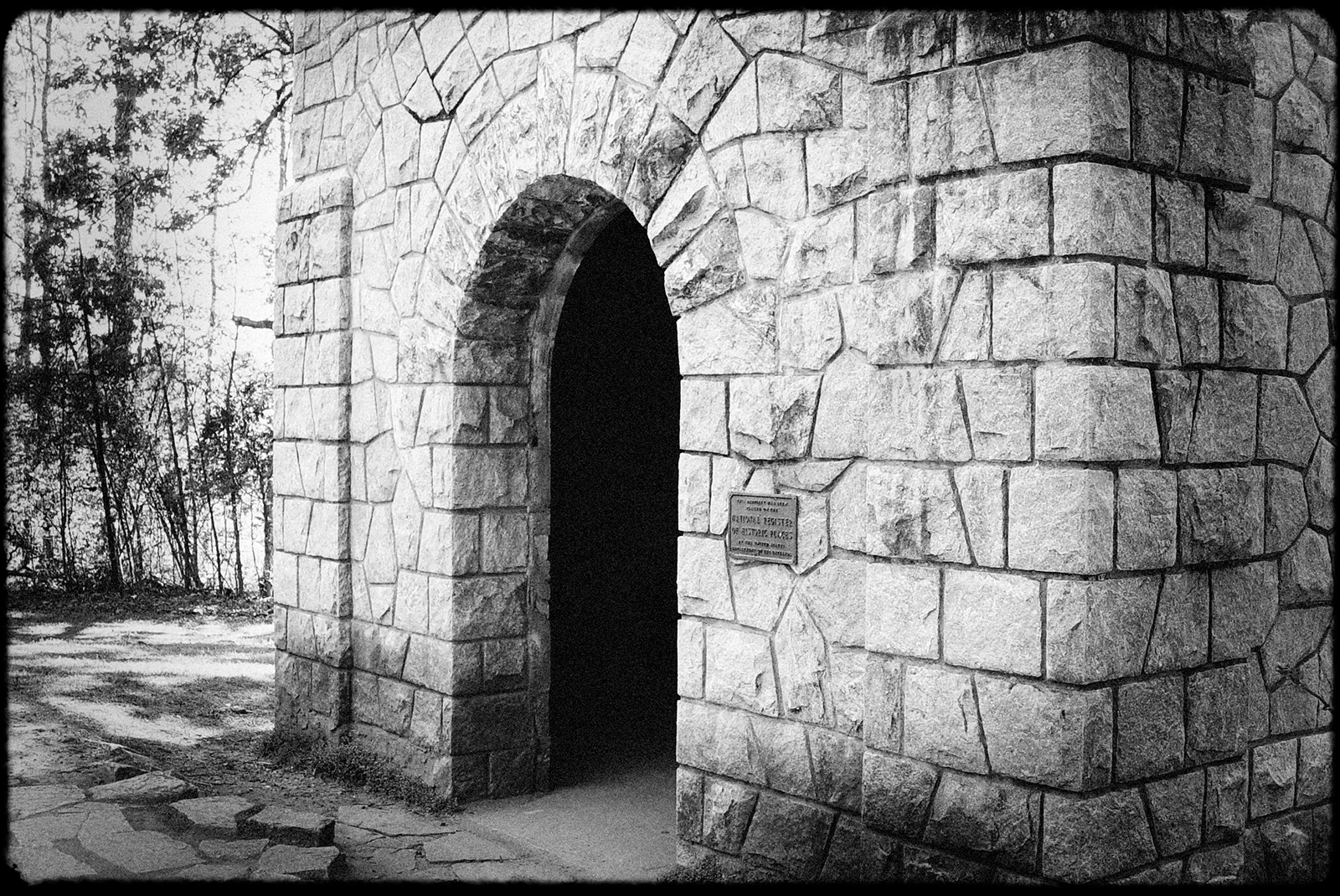

The Rock Eagle Effigy is located at the University of Georgia 4-H Center on US Highway 441 in Putnam County. Dr. A.R. Kelly of the University of Georgia, after at least a couple of years of interest in the local mounds, became involved with the WPA (Works Progress Administration) in 1936 to conduct numerous excavations and surveys at Rock Eagle. They recovered small amounts of aboriginal pottery, chipped stone, and daub, which were not considered significant and suggested to many archaeologists and others that the В“cleanВ” [sic] mound was used for religious purposes. During that time, the effigy was reconstructed to the 1877 measurements of C.C. Jones. By 1938 the fence, walkway, and tower were added to finish off the preservation of the mound, as it appears today.

At the time that Dr. A. R. Kelly of the University of Georgia and the WPA (Works Progress Administration) were excavating at the Rock Eagle Effigy, a letter dated March 23, 1936 was sent from George A. Turner of the Rural Resettlement Administration to Richard W. Smith, Secretary Treasurer of the Society of Georgia Archaeology concerning a third bird effigy. The letter referred to a map of Putnam County prepared by Turner, which showed the locations of important archaeological sites. In addition to Rock Eagle (“Scott Eagle Mound”) and Rock Hawk (“Sparta Road Eagle”) he identified the following mound, which became known as the Pressley (Presley) Mound: “No.3, Northwest of Eatonton on the Eatonton-Godfrey road is known as the old Pressley place. There is, at this time a large pile of rock, and someone stated that this pile of rock was once in the same shape of the Scott Eagle Mound but was destroyed by moving part of the rock. Indian relics have been found near this location."

Source: https://rockhawk.org/effigies/

That's the most involved information I can find on the Pressley effigy, and I wonder if it was located around the area where used to be the Presley Grist Mill, near Godfrey Road and Glades Road, that was still in operation in 1936. It seems to have been about 7 miles from Rock Eagle, and 20 miles from Rock Hawk.

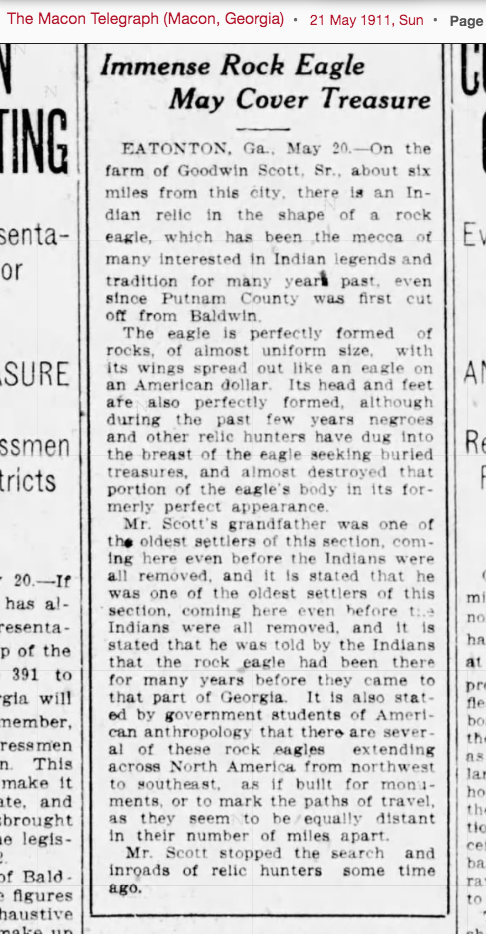

The Macon Telegraph, in May of 1911, had an article on Rock Eagle, but mentions nothing about Rock Hawk or the Pressley site.

The Macon Telegraph, on 16 August of 1914, published an article on Rock Eagle that went further into its then known history. Rock Hawk is also described.

Though given the names "Rock Eagle" and "Rock Hawk", no one knows what raptors these birds represent, only that they are raptors.

On Amazon, for sale for $208 in the Kindle version, $220 hardback, is the book by Christopher Carr, Being Scioto Hopewell: Ritual Drama and Personhood in Cross-Cultural Perspective. I would love to have that book, but the price puts it way out of my range. It has a section dealing with Rock Eagle and Rock Hawk, a few pages of which can be viewed in preview on Google Books, and so I've screengrabbed those publicly available pages and placed them below for ease in reading.

A comparison is made with the Hopewellian North Benton and Sugar Run bird effigies, while the Rock Eagle and Rock Hawk effigies have wingspans four times larger than those of Sugar Run and North Benton, and Rock Eagle's quartzite rock enclosure was nine times larger than North Benton. Rock Eagle and Rock Hawk are stated to be very similar in size, both about 102 feet head to tail, and 120 to 132 feet wing tip to wing tip. Rock Hawk is composed of about 1.3 million pounds (665 tons) of quartzite, Rock Eagle being similar. Quartzite boulders capable of being ported by one to three persons were the primary building blocks of Rock Eagle, interstices filled with smaller fragments, these transported from a local area.

While they depict raptors, Rock Eagle being fully bird-like, Rick Hawk is stated to be instead a bird-human composite, with a bird's upper body and human-like abdomen and legs. Both fly in general toward the rising sun but Rock Eagle to the northeast and Rock Hawk toward the southeast. Both are on the crests of ridges, "appropriate locations for a bird to take off from in flight." Notable is that they aren't accompanied by other clan-focused effigies, as with other Effigy Mount peoples. While Rock Eagle, which did have cremated human remains, is given as suggesting the "native idea of a large bird that carries souls of the dead to an afterlife", the Rock Hawk effigy, which has not been excavated, "allows a broader range of possible interpretations" such as also allowing for the metamorphosis of the human soul into that of a bird at death, or...

...a shaman who has transformed into a bird, is in soul-flight, and serves as a psychopomp guiding souls of the deceased to an afterlife; or a thunderbird human-bird composite who has come for the souls of the deceased to take them to an afterlife. The thunderbird interpretation is viable given that thunderbirds are raptors and the Rock Hawk effigy has raptorial elements. Moreover, the effigy's form has good resemblance to how some thunderbirds were depicted in rock art, on pottery, on woven fiber bags, on birth bark, and on other media in the northern Woodlands. The images have a bird's upper body with curved or drooping wings and a human-like rectanguloid abdomen and splayed legs.

It's also conjectured...

...If the Rock Hawk bird-human effigy was not associated with mortuary activities, it might also represent the experience of soul flight as a bird during trance or dreaming--by a shaman to do any number of tasks for his community, or by members of a sodality or -specific ceremonial society who tranced together periodically in order to merge with their bird guardian spirits and transform into birds for corporate or individual purposes. These community scale interpretations seem more relevant than others involving only one individual, such as an ordinary person in private ceremony merging with his or her bird guardian spirit and transforming into a bird, or a vision seeker doing the same, given the large size of the Rock Hawk mound.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

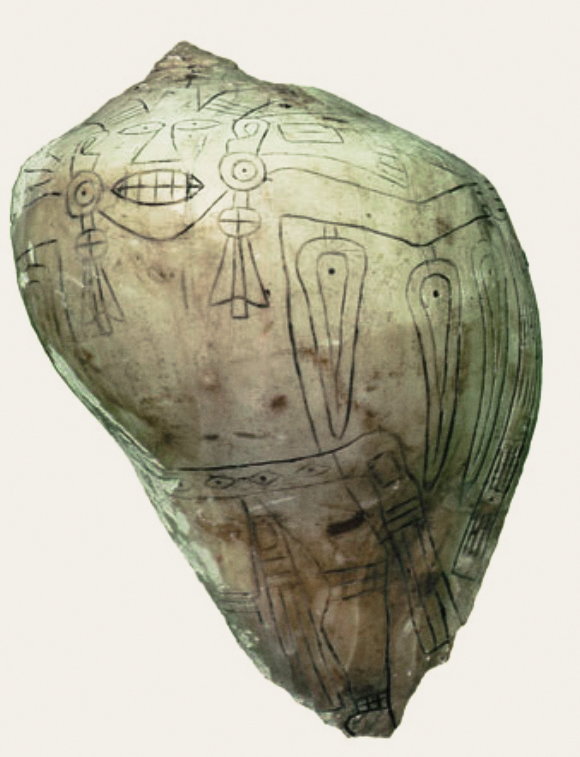

Now seems a good time to present a circa 1000 CE Mississippian (Oklahoma) conch shell incised with the design of a flying shaman wearing sun circle ear plugs and with feathers that double as winged eyes. From the Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C.

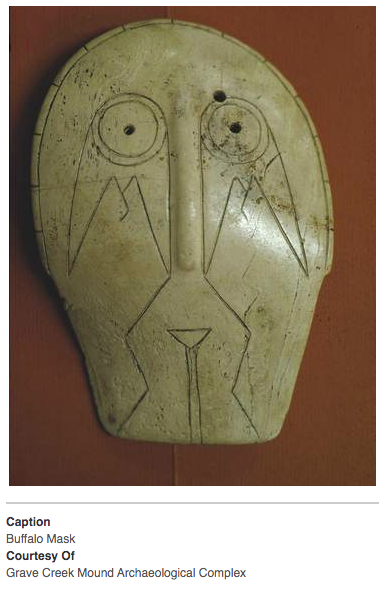

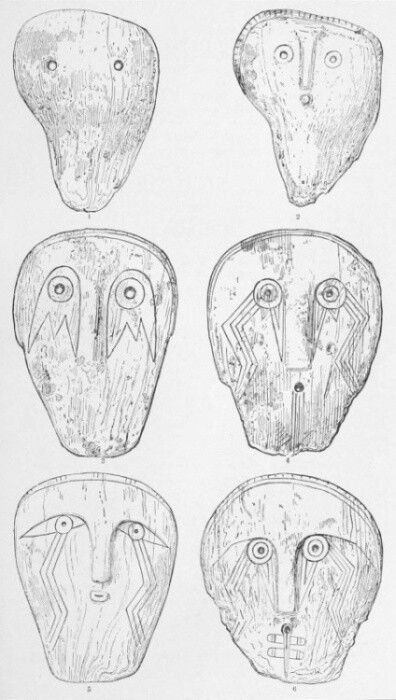

Given as produced from about 1000 CE into the 1600s, the Thunderbird was depicted on masks carved on lightning welk shells (conchs) that were worn as gorgets around the neck. Associated with the Thunderbird, or raptor, was the "weeping eye" motif shown on some masks. The below Thunderbird Mask is called the "Buffalo Mask" as it is from the Buffalo prehistoric site in Putnam County, West Virginia.

PART THREE

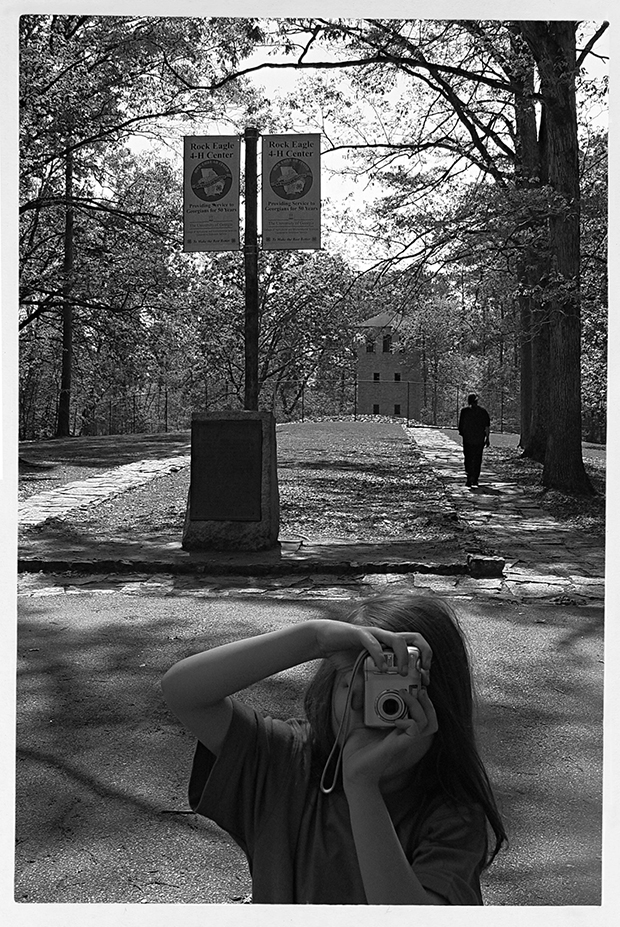

There, the building blocks are in place for my account of my visit to Rock Eagle with my husband and son in April of 2006. At the time there wasn't a lot of information about Rock Eagle online, just the minimal, nothing like what I've given above.

In 2006, if I remember correctly, all that was at Rock Eagle was the mound and the observation tower and a plaque that has a brief couple of sentences on the mound, so if you just follow the signs from the highway with no prior knowledge of the mound the only resource for knowledge on the mound are those few words.

ROCK EAGLE MOUND

MOUND OF PREHISTORIC ORIGIN, BELIEVED TO BE CEREMONIAL MOUND, MADE WITH WHITE QUARTZ ROCKS IN THE SHAPE OF AN EAGLE, HEAD TURNED TO EAST, LENGTH 102 FEET, SPREAD OF WINGS 120 FEET, DEPTH OF BREAST 8 FEET. ONLY TWO SUCH CONFIGURATIONS DISCOVERED EAST OF THE MISSISSIPPI RIVER. BOTH ARE IN PUTNAM COUNTY.

"TREAD SOFTLY HERE WHITE MAN FOR LONG ERE YOU CAME STRANGE RACES LIVED, FOUGHT AND LOVED."

ERECTED BY THE GEORGIA SOCIETY COLONIAL DAMES OF THE XVII CENTURY

JUNE 1940

I have come across a couple of videos that show there is now a nice interpretive board up with information not only on Rock Eagle, but Rock Hawk and even the Pressley Site and a possible Serpent mound. Included are even topographical maps showing changes to the mounds over time. There is also now an interpretive presentation at Rock Hawk's observation tower and trails. The serpent mound is given as having been 200 feet long and composed of three rock piles and a triangular head. Some minimal evidence of it is stated to have been visited in 2004, as with the Pressley mound, but I can find nothing else about it online. As for the Pressley mound, the interpretive board states it was dismantled, the land's owner allowing the rock from it to be used for road fill.

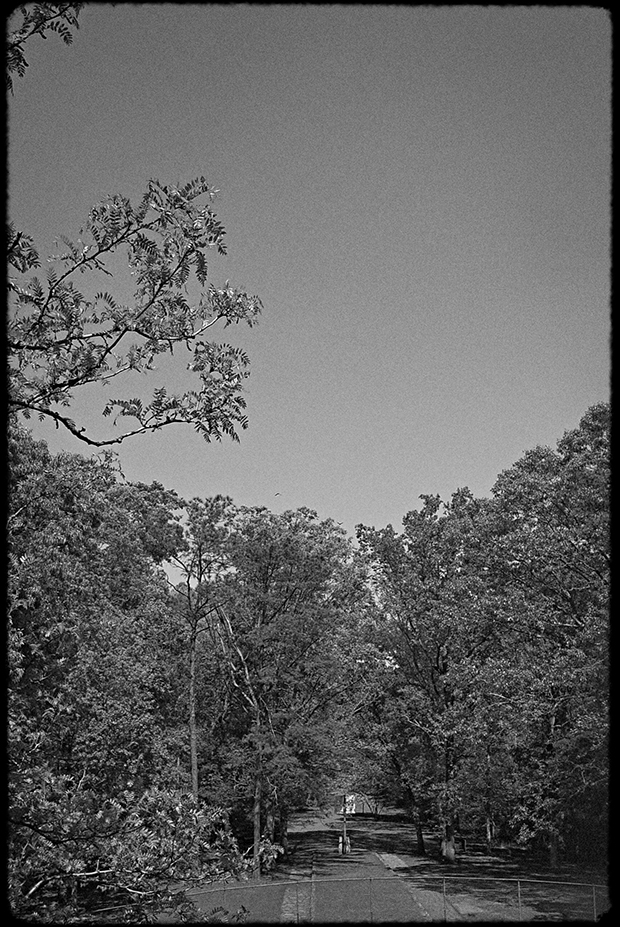

When we arrived at Rock Eagle, in 2006, it was as another couple was leaving, no one else was there, and we were left with the entire site to ourselves throughout the duration of our visit. As we approached the mound from the parking lot, three raptors came flying in and made several circling passes directly over the area of the mound and then flew off. I managed to get a couple of poor shots of them but it was quite something to be at the mound and watch the shadows of the raptors on it as they circled overhead.

With a little imagination, one might consider how impressive it is that the mound has survived--but it was built to survive. A million pounds of quartzite that's carried in means a million pounds of quartzite that would need to be carried out for complete dismantling. That may be easily doable with machinery now but not so long ago it would have been back-breaking heavy labor over a considerable period of time.

A page on Rock Eagle, put up by Brian Collier in 2000, describes the excavation:

In 1933, Rock Eagle was dismantled and trenches were dug to gain clues as to who built the mound and why. The archaeologists did not uncover the usual artifacts found in burial mounds. Instead, they were left scratching their heads over four odd layers of soil. The first was humus and soil mixed, below that was an area of red clay, then below that was a layer of yellow-brown clay and loam, and below that was the basic red clay found all over Georgia.

As the head, neck and shoulder of the eagle were carefully taken apart, a belt of hard yellow clay was uncovered beneath the quartz. Another trench was cut into the heart of the bird where small fragments of charcoal were found. The floor was made of small head-sized stones imbedded in burned soil and burned organic matter from six to eight inches thick. Below this was a layer of yellowish brown clay similar to the clay found in the first trench, but still no sign of any artifacts or evidence of burial.

The archaeologists then excavated from the tail, where they discovered a boulder from which the eagle had presumably been started. In about a yard square between this and another boulder, the workers found fragments of unburned human, bird, and animal bones. They also uncovered a small, ovate pointed tool also made of quartz. After this, excavation ended.

Read more: https://flanneryoconnor.com/pieagle.html#ixzz7dUEWc1Wr Under Creative Commons License: Attribution Non-Commercial

There is sometimes a muddle of information on the mound on the internet. I have read the quartzite was from the area, and that it was instead ported in from about forty miles away. I've read that there were three types of clay used and that these weren't from this area of Putnam county, again materials that needed to be imported. I've read the effigy likely began with the construction of the central mound, and that the appearance of the bird was added later. But reading of the preparation of the area, one wonders if this is the case, or if it was always intended to be this raptor. Some sites say there was a quartzite circle around Rock Hawk, and others say there was one around Rock Eagle. The Being Scioto Hopewell book hazards that it may have once been surrounded by a woodhenge or screen, but excavations make no mention of any such findings. With a little imagination, one wonders if trees hemmed in the mound or if the environ of the mound was kept clear of them and thus any tree canopy. One may wonder about vegetation that would naturally try to take sprout amongst the rocks (when I was there, a plant was growing in a part of the tail) and, assuming that vegetation would have been regularly cleared away, what was the arrangement for this, whose responsibility was it--an individual's or that of the collective. One may wonder how close was community life to the mound, and what were the ceremonies that took place there. I have read that the area around the mound was burned to clear it of vegetation, which has made dating the mound difficult, but it wasn't clarified whether these burns were conducted by white settlers or by the Indians who constructed and cared for the mound.

The mound needs to be circled with a fence to keep people off of it and to prevent individuals from walking off with the rocks but the modern chain-link metal of the fence cuts off the ability to appreciate the mound in an unalienated manner, for which the observation tower seems a sort of uneven compensation. There was no tower in the past, of course, and if there was no fence I wouldn’t have felt a need for the tower. Not that I really felt a crying need for the tower as I had stood outside the fence looking at the effigy. For, in a sense, the raptors that came and circled overhead, while we were there, were themselves a tower. As I stood there and watched their shadows, I could see and feel the full form of the effigy via them. Their arrival, their circling the area and their shadows made the tower feel almost superfluous. And as I stooc there, I was glad they had come to complement our visit with their presence.