STANLEY KUBRICK'S BARRY LYNDON

Shot-by-Shot Analysis

Part Five

Go to TOC for this film ( (which has also a statement on purpose and manner of analysis and a disclaimer as to caveat emptor and my knowing anything authoritatively, which I do not, but I do try to not know earnestly, with some discretion, and considerable thought).

TOC and Supplemental Posts | Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6 | Part 7 | Films Home

LINKS TO SECTIONS OF THE ANALYSIS ON THIS PAGE:

Barry and Lady Lyndon Wed, Shots 495 through 502

Notes on Barry and Lady Lyndon Wed. Book versus film. Location.

Newlywed Difficulties; The Birth of Bryan, Shots 503 through 528

Notes on Newlywed Difficulties; The Birth of Bryan. Book versus film.

The Carriage Ride to Lady Lyndon's Estate (The Misdirection with the Horses)

The Confusion of the Two Facades for Lady Lyndon's Estate and the Stourhead Garden

The Last Game and the Poetry in the Bath

Bullingdon's First Whipping, Shots 529 through 548

Notes on Bullingdon's First Whipping. Book versus film.

The Turban

Bryan's Birthday, Shots 549 through 554

Magic and Misdirection--Who is the Story About

The Bedtime Tale and the Fear of the Dark, Shots 556 through 561

Notes on the Bedtime Tale and the Fear of the Dark. Book versus film.

Securing Barry and Bryan's Future, Shots 562 through 567

Notes on Securing Barry and Bryan's Future. Book versus film.

Stourhead and Aeneas' Journey in the Underworld--Begone, You Who Are Uninitiated

The labyrinth, the minotaur, and the doors of Apollo's temple.

The Attempt to Secure a Title, Shots 568 through 580

Notes on The Attempt to Secure a Title. Book versus film. Locations.

Alive or Dead

Ludovico and Hallam and the Significance of the Peerage

The Minister of the Interior, who chose Alex for the Ludovico experiment, as the individual who manages Barry in his pursuit of a peerage, during which we see a Ludovico painting.

The Reception Line

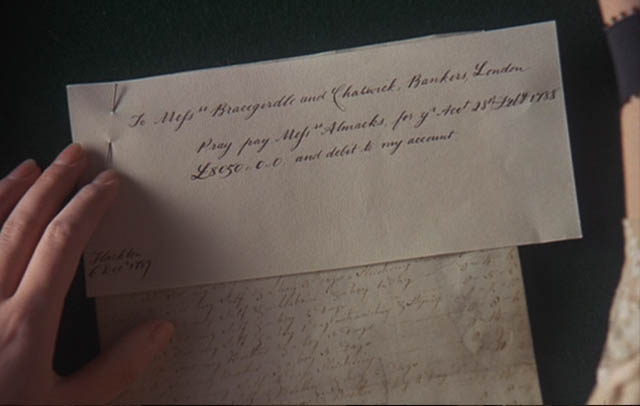

A Problem with Dates

Bullingdon's Second Whipping, Shots 581 through 604

Notes on Bullingdon's Second Whipping. Book versus film.

Hamlet

The Disappearing Pencil

Bullingdon's Revolt, Shots 605 through 635

Notes on Bullingdon's Revolt. Book versus film. Recycling the Shoes. Recycling the music. The two reds. Location. Hamlet and the play within a play.

495 PART II. Containing an account of the misfortunes and disasters which befell Barry Lyndon. (1:42:34)

496 MS Runt officiating wedding. (1:42:47)

RUNT: Dearly beloved, we are gathered together here in the sight of God and in the...

497 Shot from right rear of Runt of Barry, Lady Lyndon, Barry's mother, little Lord Bullingdon and the Chevalier, plus guests, in chapel. (1:43:01)

RUNT: ...face of this congregation to join together this man and this woman in holy matrimony.

NARRATION: A year later, on the fifteenth of June, in the year of our Lord, seventeen hundred and seventy-three, Redmond Barry had the honour to lead to the altar the Countess of Lyndon. The ceremony was performed by the Reverend Samuel Runt, Her Ladyship's Chaplain.

498 MS Runt. (1:43:25)

RUNT: ...and therefore is not in any way to be enterprised nor taken in hand unadvisedly, lightly or wantonly, to satisfy men's carnal lusts

and appetites like brute beasts that have no understanding, but reverently...

499 MS the Chevalier, Barry, Lady Lyndon, Barry's mother, Lord Bullingdon. (1:43:48)

RUNT: ...discreetly, advisedly, soberly, and in the fear of God...

500 CU Lord Bullingdon. (1:43:58)

RUNT: ...duly considering the causes

for which matrimony was ordained. First, it was ordained for the procreation

of children to be brought up in the fear and nurture of the Lord...

501 Barry and Lady Lyndon. (1:44:10)

RUNT:

...and to the praise of His holy name. Secondly, it was ordained for a...

502 CU Barry. (1:44:17)

RUNT: ...remedy

against sin, and to avoid fornication.

NARRATION :

Barry had now arrived

at the pitch of prosperity...

495 |

496 |

497 |

498 |

499 |

500 |

501 |

502 |

Kubrick leaves out Barry's intense pressures upon Lady Lyndon in his pursuit of her.

Of course I despatched a courier in my liveries to Castle Lyndon with a private letter for Runt, demanding from him full particulars of the Countess of Lyndon's state of health and mind; and a touching and eloquent letter to her Ladyship, in which I bade her remember ancient days, which I tied up with a single hair from the lock which I had purchased from her woman, and in which I told her that Sylvander remembered his oath, and could never forget his Calista. The answer I received from her was exceedingly unsatisfactory and inexplicit; that from Mr. Runt explicit enough, but not at all pleasant in its contents. My Lord George Poynings, the Marquess of Tiptoff's younger son, was paying very marked addresses to the widow; being a kinsman of the family, and having been called to Ireland relative to the will of the deceased Sir Charles Lyndon.

Barry duels with poor George later.

As ill-luck would have it for him, he appeared in Dublin a very short time afterwards; was introduced to the Chevalier Redmond Barry, at the Lord Lieutenant's table; adjourned with him and several other gentlemen to the club at 'Daly's,' and there, in a dispute about the pedigree of a horse, in which everybody said I was in the right, words arose, and a meeting was the consequence. I had had no affair in Dublin since my arrival, and people were anxious to see whether I was equal to my reputation. I make no boast about these matters, but always do them when the time comes; and poor Lord George, who had a neat hand and a quick eye enough, but was bred in the clumsy English school, only stood before my point until I had determined where I should hit him.

My sword went in under his guard, and came out at his back. When he fell, he good-naturedly extended his hand to me, and said, 'Mr. Barry, I was wrong!' I felt not very well at ease when the poor fellow made this confession: for the dispute had been of my making, and, to tell the truth, I had never intended it should end in any other way than a meeting.

Barry manages to persuade George to no longer pursue Lady Lyndon when George finds that she is sending to him the same poetry she has sent Barry (who she has denied even knowing previously).

Barry pursues and she flees. She calls him a terrible man and begs him to leave her alone. He bribes one of her servants to bring her letters to him to read. He bribes a fortune teller to tell her he is to be her future husband. "Can this monster," she wrote in a letter, "indeed do as he boasts, and bend even Fate to his will?" She was both horrified by him and fascinated by him. She flees to London.

Her Ladyship had a house in Berkeley Square, London, more splendid than that which she possessed in Dublin; and, knowing that she would come thither, I preceded her to the English capital, and took handsome apartments in Hill Street, hard by. I had the same intelligence in her London house which I had procured in Dublin. The same faithful porter was there to give me all the information I required. I promised to treble his wages as soon as a certain event should happen. I won over Lady Lyndon's companion by a present of a hundred guineas down, and a promise of two thousand when I should be married, and gained the favours of her favourite lady's-maid by a bribe of similar magnitude. My reputation had so far preceded me in London that, on my arrival, numbers of the genteel were eager to receive me at their routs. We have no idea in this humdrum age what a gay and splendid place London was then: what a passion for play there was among young and old, male and female; what thousands were lost and won in a night; what beauties there were—how brilliant, gay, and dashing! Everybody was delightfully wicked: the Royal Dukes of Gloucester and Cumberland set the example; the nobles followed close behind. Running away was the fashion. Ah! it was a pleasant time; and lucky was he who had fire, and youth, and money, and could live in it! I had all these; and the old frequenters of 'White's,' 'Wattier's,' and 'Goosetree's' could tell stories of the gallantry, spirit, and high fashion of Captain Barry.

The progress of a love-story is tedious to all those who are not concerned, and I leave such themes to the hack novel-writers, and the young boarding-school misses for whom they write. It is not my intention to follow, step by step, the incidents of my courtship, or to narrate all the difficulties I had to contend with, and my triumphant manner of surmounting them. Suffice it to say, I DID overcome these difficulties. I am of opinion, with my friend the late ingenious Mr. Wilkes, that such impediments are nothing in the way of a man of spirit; and that he can convert indifference and aversion into love, if he have perseverance and cleverness sufficient. By the time the Countess's widowhood was expired, I had found means to be received into her house; I had her women perpetually talking in my favour, vaunting my powers, expatiating upon my reputation, and boasting of my success and popularity in the fashionable world.

Also, the best friends I had in the prosecution of my tender suit were the Countess's noble relatives; who were far from knowing the service that they did me, and to whom I beg leave to tender my heartfelt thanks for the abuse with which they then loaded me! and to whom I fling my utter contempt for the calumny and hatred with which they have subsequently pursued me.

The chief of these amiable persons was the Marchioness of Tiptoff, mother of the young gentleman whose audacity I had punished at Dublin. This old harridan, on the Countess's first arrival in London, waited upon her, and favoured her with such a storm of abuse for her encouragement of me, that I do believe she advanced my cause more than six months' courtship could have done, or the pinking of a half-dozen of rivals. It was in vain that poor Lady Lyndon pleaded her entire innocence and vowed she had never encouraged me. 'Never encouraged him!' screamed out the old fury; 'didn't you encourage the wretch at Spa, during Sir Charles's own life? Didn't you marry a dependant of yours to one of this profligate's bankrupt cousins? When he set off for England, didn't you follow him like a mad woman the very next day? Didn't he take lodgings at your very door almost—and do you call this no encouragement? For shame, madam, shame! You might have married my son—my dear and noble George; but that he did not choose to interfere with your shameful passion for the beggarly upstart whom you caused to assassinate him; and the only counsel I have to give your Ladyship is this, to legitimatise the ties which you have contracted with this shameless adventurer; to make that connection legal which, real as it is now, is against both decency and religion; and to spare your family and your son the shame of your present line of life.'

With this the old fury of a marchioness left the room, and Lady Lyndon in tears: I had the whole particulars of the conversation from her Ladyship's companion, and augured the best result from it in my favour.

Thus, by the sage influence of my Lady Tiptoff, the Countess of Lyndon's natural friends and family were kept from her society. Even when Lady Lyndon went to Court the most august lady in the realm received her with such marked coldness, that the unfortunate widow came home and took to her bed with vexation. And thus I may say that Royalty itself became an agent in advancing my suit, and helping the plans of the poor Irish soldier of fortune. So it is that Fate works with agents, great and small; and by means over which they have no control the destinies of men and women are accomplished.

I shall always consider the conduct of Mrs. Bridget (Lady Lyndon's favourite maid at this juncture) as a masterpiece of ingenuity: and, indeed, had such an opinion of her diplomatic skill, that the very instant I became master of the Lyndon estates, and paid her the promised sum—I am a man of honour, and rather than not keep my word with the woman, I raised the money of the Jews, at an exorbitant interest—as soon, I say, as I achieved my triumph, I took Mrs. Bridget by the hand, and said, "Madam, you have shown such unexampled fidelity in my service that I am glad to reward you, according to my promise; but you have given proofs of such extraordinary cleverness and dissimulation, that I must decline keeping you in Lady Lyndon's establishment, and beg you will leave it this very day:" which she did, and went over to the Tiptoff faction, and has abused me ever since.

But I must tell you what she did which was so clever. Why, it was the simplest thing in the world, as all master-strokes are. When Lady Lyndon lamented her fate and my—as she was pleased to call it—shameful treatment of her, Mrs. Bridget said, 'Why should not your Ladyship write this young gentleman word of the evil which he is causing you? Appeal to his feelings (which, I have heard say, are very good indeed—the whole town is ringing with accounts of his spirit and generosity), and beg him to desist from a pursuit which causes the best of ladies so much pain? Do, my Lady, write: I know your style is so elegant that I, for my part, have many a time burst into tears in reading your charming letters, and I have no doubt Mr. Barry will sacrifice anything rather than hurt your feelings.' And, of course, the abigail swore to the fact.

'Do you think so, Bridget?' said her Ladyship. And my mistress forthwith penned me a letter, in her most fascinating and winning manner:—'Why, sir,' wrote she, 'will you pursue me? why environ me in a web of intrigue so frightful that my spirit sinks under it, seeing escape is hopeless from your frightful, your diabolical art? They say you are generous to others—be so to me. I know your bravery but too well: exercise it on men who can meet your sword, not on a poor feeble woman, who cannot resist you. Remember the friendship you once professed for me. And now, I beseech you, I implore you, to give a proof of it. Contradict the calumnies which you have spread against me, and repair, if you can, and if you have a spark of honour left, the miseries which you have caused to the heart-broken

'H. LYNDON.'

What was this letter meant for but that I should answer it in person? My excellent ally told me where I should meet Lady Lyndon, and accordingly I followed, and found her at the Pantheon. I repeated the scene at Dublin over again; showed her how prodigious my power was, humble as I was, and that my energy was still untired. 'But,' I added, 'I am as great in good as I am in evil; as fond and faithful as a friend as I am terrible as an enemy. I will do everything,' I said, 'which you ask of me, except when you bid me not to love you. That is beyond my power; and while my heart has a pulse I must follow you. It is MY fate; your fate. Cease to battle against it, and be mine. Loveliest of your sex! with life alone can end my passion for you; and, indeed, it is only by dying at your command that I can be brought to obey you. Do you wish me to die?'

She said, laughing (for she was a woman of a lively, humorous turn), that she did not wish me to commit self-murder; and I felt from that moment that she was mine.

A year from that day, on the 15th of May, in the year 1773, I had the honour and happiness to lead to the altar Honoria, Countess of Lyndon, widow of the late Right Honourable Sir Charles Lyndon, K.B. The ceremony was performed at St. George's, Hanover Square, by the Reverend Samuel Runt, her Ladyship's chaplain. A magnificent supper and ball was given at our house in Berkeley Square, and the next morning I had a duke, four earls, three generals, and a crowd of the most distinguished people in London at my LEVEE. Walpole made a lampoon about the marriage, and Selwyn cut jokes at the 'Cocoa-Tree.' Old Lady Tiptoff, although she had recommended it, was ready to bite off her fingers with vexation; and as for young Bullingdon, who was grown a tall lad of fourteen, when called upon by the Countess to embrace his papa, he shook his fist in my face and said, 'HE my father! I would as soon call one of your Ladyship's footmen Papa!'

But I could afford to laugh at the rage of the boy and the old woman, and at the jokes of the wits of St. James's. I sent off a flaming account of our nuptials to my mother and my uncle the good Chevalier; and now, arrived at the pitch of prosperity, and having, at thirty years of age, by my own merits and energy, raised myself to one of the highest social positions that any man in England could occupy, I determined to enjoy myself as became a man of quality for the remainder of my life.

Before quitting London, I procured His Majesty's gracious permission to add the name of my lovely lady to my own; and henceforward assumed the style and title of BARRY LYNDON, as I have written it in this autobiography.

So, Barry is a cad and delights at presenting himself as such, and in his torments of Lady Lyndon who he is confidant he will overwhelm. Lady Lyndon he gives as a somewhat flighty woman, rather naive, superstitious. She hardly seems the picture of dignified nobility as depicted in the film, but how much of his account are we to trust? Perhaps a fair amount as regards her distress and naivety and even a certain amount of duplicity in her denying she had ever known him. But it also appears that she is honestly terrified of him.

What no doubt was attractive to Kubrick was how much fate or self will had to do with their coupling. Due Barry's machinations, Lady Lyndon begins to become persuaded that she can't escape him. He is her fate.

The chapel at Petworth House serves as location for the wedding ceremony.

503 Landscape shot, two carriages in the distance traveling down a road. (1:44:29)

Begin Vivaldi's Cello Sonata in E Minor, RV 40, 3rd Movement, Largo. Manuscript.

NARRATION: ...and by his own energy had raised

himself to a higher sphere of society, having procured His Majesty's

gracious permission to add the name of his lovely Lady...

504 Shot from front of the carriages traveling toward the right of the camera. (1:44:44)

Middle of 2nd measure of Movement.

NARRATION: ...to his own. Thenceforth, Redmond Barry assumed the style and title of Barry Lyndon.

505 CU of Barry and Lady Lyndon in the carriage, Barry smoking. (1:44:57)

Middle of 3rd measure of Movement at the beginning of this scene. Begin repeat of first 5 measures as Lady Lyndon speaks.

LADY LYNDON: Redmond, would you mind not smoking

for a while? Redmond?

Barry blows smoke in her face then kisses her.

NARRATION:

Lady Lyndon was soon destined

to occupy a place in Barry's life not very much more important

than the elegant carpets and pictures which would form

the pleasant background of his existence.

506 LS The two carriages. (1:46:06)

In 4th measure of Movement switch to this scene. After the first 5 are done, continue with the next 5 measures.

507 Lord Bullingdon and Runt in their carriage. (1:46:13)

5th measure of Movement switch to this scene.

RUNT: My Lord Bullingdon, you seem particularly glum today. You should be happy that your mother has remarried.

LORD BULLINGDON:

Not in this way. And not in such haste. And certainly not to this man.

RUNT:

I think you judge your mother too harshly. Do you not like your new father?

LORD BULLINGDON:

Not very much. He seems to me little more than a common opportunist. I don't think he loves my mother at all and it hurts me to see her make such a fool of herself.

503 |

504 |

505 |

506 |

507 |

|

508 CU of infant. Zoom out to show the Lady and Barry as well. (1:47:10)

Switch in 10th measure of Movement. And begin repeat of the latter 5 measures.

NARRATION: At the end of a year Her Ladyship

presented Barry with a son. Bryan Patrick Lyndon, they called him.

End the Vivaldi in the 2nd measure of the repeat of the latter 5 measures.

509 Barry passionately embracing two half-naked women. (1:47:36)

NARRATION: Her Ladyship and Barry lived, after a while, pretty separate.

510 The Lady and Lord Bullingdon reclining. Zoom out. (1:47:59)

Flute music.

NARRATION:

She preferred quiet, or to say the truth, he preferred it for her, being a great friend to a modest and tranquil behaviour in woman. Besides, she was a mother, and would have great comfort in the dressing, educating and dandling of their little Bryan, for whose sake it was fit,

Barry believed, that she should give up the pleasures...

511 Night. Lady Lyndon plays the harpsichord, Runt on flute and Bullingdon on cello. (1:48:25)

NARRATION: ...and frivolities of the world, leaving that part of the duty of every family of distinction to be performed by him.

512 Lord Bullingdon on cello. (1:48:36)

513 CU Lady Lyndon. (1:48:45)

512 |

513 |

514 LS across a lake of their estate. (1:48:57)

515 In a garden, Runt, Lady Lyndon and Bullingdon take a walk. (1:49:05)

514 |

515 |

516 View through trees across the water. (1:49:19)

Zoom in on Barry kissing the baby's governess.

517 CU of Lady Lyndon's hand and Lord Bullingdon taking it. (1:49:36)

As Bullingdon reaches for and takes his mother's hand, begin Vivaldi's Cello Sonata in E Minor, RV 40, 3rd Movement, Largo. Manuscript.

518 CU of Lord Bullingdon. (1:49:42)

519 Barry kissing the governess. (1:49:46)

He looks up and sees his family.

520 CU Lady Lyndon. (1:49:58)

NARRATION:

Lady Lyndon tended to a melancholy

and maudlin temper...

521 Runt, the Lady and Bullingdon turn and walk back down the path. (1:50:04)

NARRATION: ...and, left alone by her husband, was rarely happy or in good humour. Now she must add jealousy to her other complaints and find rivals even among her maids.

517 |

518 |

519 |

520 |

522 Night. The Lady and Runt play cards with two other women. (1:50:22)

Zoom in slowly. The Lady yawns.

Scene has switched in the middle of the 4th measure of the Vivaldi. When done with first five measures, repeat and continue to 5th measure.

LADY LYNDON:

Samuel, what would the time be?

RUNT:

Twenty-five minutes past eleven, my Lady.

LADY LYNDON:

Shall we make this the last game, ladies?

UNISON: Yes.

523 CU of Lady Lyndon in her bath. Zoom out. (1:51:13)

Begin the 5th measure of the movement as the scene begins.

One of the ladies in waiting recites poetry.

LADY IN WAITING: Les cœurs, l'un par l'autre attirés Se communiquent leur substance; Tels deux miroirs ardents, l'un à l'autre opposés ; Concentrent la lumière, et se la réfléchissent : Les rayons tour-à-tour recueillis... divisés, En se multipliant s’accroissent, s'embellissent ; Et d'autant plus actifs, qu'ils se sont plus croisés, Au même point se réunissent. Quel spectacle je vois, sur un lit verduyant, enrichi de l'email de maintes fleures naissantes.

La Jouissance in Les sens, poème en six chants de Barnabé Farmian Durosoy.

Hearts , one by the other attracted Communicate their substance; Like two burning mirrors , one opposite to the other ; Focus light and reflect it : Turn - to - turn, rays collected ... divided By multiplying increase, will embellish ; And even more, they are crossed , the same point meet...

524 Doors. Barry enters. (1:51:56)

BARRY: Good morning, ladies.

LADIES IN WAITING: Good morning, sir.

BARRY: Would you mind excusing us? I'd like a word alone with Lady Lyndon.

525 LS of Lady Lyndon and her ladies. (1:52:07)

The two women rise and leave.

526 The women pass by Barry and out the door. (1:52:17)

Begin repeat of the 2nd 5 measures of the Movement as the women exit.

He crosses over to stand beside the tub.

BARRY:

I'm sorry.

527 Lady Lyndon in her bath. (1:52:36)

528 CU as the two kiss. (1:52:53)

523 |

524 |

525 |

526 |

527 |

528 |

The carriage ride dialogue between Runt and Bullingdon doesn't occur in the novel.

The incident with the pipe is in the novel, though handled differently. In the film, it is a subtle but very disturbing scene, the inflection of derision and spite that is observed in Barry's expression after he's blown the smoke in Lady Lyndon's face, made even more disturbing by his duplicity, his dropping of his mask then his putting it back on when he decides to smile at Lady Lyndon as if to suggest this was all a joke. And we see in her face, as he turns away, her fullest realization of what she has gotten herself into.

Barry's contempt is vicious, his disregard for her as cold as it gets. He has what he wants. Almost. Next, he needs to secure his position, part of which will be accomplished with the birth of Bryan, for whom he will have a real and passionate love. The way I look at it, is that love begins to extend from Bryan to Lady Lyndon in the film, he learns compassion through his son, but it will not begin to be enough to bond him with Lady Lyndon after Bryan's death.

From the book:

The first days of a marriage are commonly very trying; and I have known couples, who lived together like turtle-doves for the rest of their lives, peck each other's eyes out almost during the honeymoon. I did not escape the common lot; in our journey westward my Lady Lyndon chose to quarrel with me because I pulled out a pipe of tobacco (the habit of smoking which I had acquired in Germany when a soldier in Billow's, and could never give it over), and smoked it in the carriage; and also her Ladyship chose to take umbrage both at Ilminster and Andover, because in the evenings when we lay there I chose to invite the landlords of the 'Bell' and the 'Lion' to crack a bottle with me. Lady Lyndon was a haughty woman, and I hate pride; and I promise you that in both instances I overcame this vice in her. On the third day of our journey I had her to light my pipematch with her own hands, and made her deliver it to me with tears in her eyes; and at the 'Swan Inn' at Exeter I had so completely subdued her, that she asked me humbly whether I would not wish the landlady as well as the host to step up to dinner with us...

Bullingdon lives elsewhere. And he quotes Hamlet to his mother, which I find hilarious and am a little disappointed Kubrick didn't include this in the film.

At the end of a year Lady Lyndon presented me with a son—Bryan Lyndon I called him, in compliment to my royal ancestry: but what more had I to leave him than a noble name? Was not the estate of his mother entailed upon the odious little Turk, Lord Bullingdon? and whom, by the way, I have not mentioned as yet, though he was living at Hackton, consigned to a new governor. The insubordination of that boy was dreadful. He used to quote passages of 'Hamlet' to his mother, which made her very angry. Once when I took a horsewhip to chastise him, he drew a knife, and would have stabbed me: and, 'faith, I recollected my own youth, which was pretty similar; and, holding out my hand, burst out laughing, and proposed to him to be friends. We were reconciled for that time, and the next, and the next; but there was no love lost between us, and his hatred for me seemed to grow as he grew, which was apace...

Her Ladyship and I lived, after a while, pretty separate when in London. She preferred quiet: or to say the truth, I preferred it; being a great friend to a modest tranquil behaviour in woman, and a taste for the domestic pleasures. Hence I encouraged her to dine at home with her ladies, her chaplain, and a few of her friends; admitted three or four proper and discreet persons to accompany her to her box at the opera or play on proper occasions; and indeed declined for her the too frequent visits of her friends and family, preferring to receive them only twice or thrice in a season on our grand reception days. Besides, she was a mother, and had great comfort in the dressing, educating, and dandling our little Bryan, for whose sake it was fit that she should give up the pleasures and frivolities of the world; so she left THAT part of the duty of every family of distinction to be performed by me. To say the truth, Lady Lyndon's figure and appearance were not at this time such as to make for their owner any very brilliant appearance in the fashionable world. She had grown very fat, was short-sighted, pale in complexion, careless about her dress, dull in demeanour; her conversations with me characterised by a stupid despair, or a silly blundering attempt at forced cheerfulness still more disagreeable: hence our intercourse was but trifling, and my temptations to carry her into the world, or to remain in her society, of necessity exceedingly small. She would try my temper at home, too, in a thousand ways. When requested by me (often, I own, rather roughly) to entertain the company with conversation, wit, and learning, of which she was a mistress: or music, of which she was an accomplished performer, she would as often as not begin to cry, and leave the room. My company from this, of course, fancied I was a tyrant over her; whereas I was only a severe and careful guardian over a silly, bad-tempered, and weak-minded lady.

Shot 504 is below, preceding Barry blowing smoke in Lady Lyndon's face.

In shot 506 we observe the carriages again before Bullingdon's conversation with Runt.

I'm assuming the carriage with the red drapery is the one in which Barry and the Lady are traveling in shot 504. It is out front with white horses.

In the second shot the second darker carriage from 504 seems now to be out front, and it has white horses drawing it, so we won't notice the switch because we are focused on the white horses. Also, the black or dark horses that had been drawing the 2nd carriage are no longer observed, we instead have sable and they are drawing the carriage with the red drapery.

The location is skewed too. Shot 504 is on the same road but is actually further down it. If you look in the background there is a deep bend in the road and further back is a rather scraggly tree on the road's screen right. This bend in the road is where the carriages are in shot 506 as they drive through the sheep.

We will return to this area after Bullingdon's success over Barry in the duel, when they are riding to Lady Lyndon's estate. The shot, 762, will be as shot 504 but in light, no shadow, and we will only have the dark carriage, no red drapery, drawn by sable horses.

The camera is positioned in shot 762 in exactly the same place as shot 504. The The rocks to the left forefront are in the same places. The rocks to the right forefront are in the same places.

The disruption here, and the repeat, immediately reminds me of what happens with Barry before and after the scene with Lischen. In shot 257 we see him approaching a town before meeting her. When he leaves her home, he should be traveling on, but in shot 285 we see him approaching the same town from the opposite side. It occurs to me, what happens if we subtract 504 (the first carriage ride shot) from 762 (the repeat of it). 258 happens. This is the shot after his approach to the town in 257, when he meets Lischen, though we don't see her until shot 259. She precedes Lady Lyndon and is similar to her in that she too has a son already. Shots 257, and its opposing approach, 285, are notable because, as with the two ascents to the Overlook in The Shining, we had a center defined by an approach from two opposite sides. Also, with 504 to 762, we have the 258 shots that define, between these two carriage rides, the unsuccessful marriage of Lady Lyndon to Barry, going from the first shot just following their marriage, to Bullingdon returning home down the same road after the duel and Barry being told he will lose his leg.

It's hard to believe there are only 258 shots between those two carriage rides when so much transpires. The time occupied by the marriage is from 1:44 to 2:53 of the film, I guess about 69 minutes. Shot 258 occurs 53/54 minutes in. That's 15 minutes difference. I would never have guessed it.

One of the facades used for Barry Lyndon is that of the Wilton House. The Double Cube room in which Barry reads to his son is also located here, as is the Palladian Bridge located at Wilton House (the bridge in the scene where Barry is observed kissing the governess, and a later one immediately after his tragic confrontation with Bullingdon in the music room), which might be very easily confused for the arches bridge at Stourhead (scene of Barry speaking with his mother) though its columns are enveloped in greenery.

Another exterior of the mansion was Castle Howard which features a grand dome.

I'm going to address the bath scene by beginning with Eyes Wide Shut, for when Bill visits Sharky's and learns of the overdose of Amanda, one of the paintings on the walls is a Rossetti one of Ophelia, who goes mad after her father's death in Hamlet and supposedly drowns by suicide.

Bathtubs are used multiple times in Kubrick's films.

In Lolita, Humbert, having decided to not shoot Charlotte, presses open the door to the bathroom to find his wife isn't in her bath. She is instead reading his journal. (The one in which he'd been writing when Lolita brought him his breakfast and he read to her Ulalume.) Poor Charlotte dies anyway, in the street in the rain, hit by a car. A watery death! We even have the sense it could have been not just a matter of her being distracted but suicide, as she had taken out the gun to tell Humbert how if she found out he did not believe in God she would commit suicide, but even if it is only death by distraction it seems enough to link her with Ophelia. Later, Humbert is drunk in the tub, friends visit, see the gun, and fear he is going to commit suicide (when he's not) and burial arrangements are made for Charlotte.

In A Clockwork Orange, Alex stumbles HOME out of the rain. While he is in his bath we have the deja vu scene of his crooning "I'm singing in the rain", the writer, Alexander, hearing and going mad with rage and grief as he realizes who it is in his tub, that it is the same individual who raped his wife and paralyzed him. After this Alex is driven to commit suicide, leaping out of a window.

In The Shining, replaying Humbert's pressing open the door to the bathroom, now it is Jack doing the same in Room 237. The shower curtain is withdrawn to reveal a young woman. Jack and she kiss. In the mirror he realizes she is death.There are repeated images of her as an old woman, supposedly dead by suicide (according to the book), rising from the tub. Again, a watery death, but also a grizzly resurrection.

In 2001, Bowman confronts his aged image in a mirror over a bathtub that should remind us of the hibernation pods that became tombs. Bowman, however, will be reborn via the monolith.

In Eyes Wide Shut, the setting for Sharky's is the same as for Rainbow Fashions but Bill doesn't recognize this. Bill is not only disoriented by having been followed, he had also learned that evening Domino was ill. Her apartment has the bathtub under the cherub card. When they kissed we were given a view of a book titled Shadows in the Mirror or something like that (so lazy, look it up, Juli). In Sharky's, the portrait of Ophelia is hung on the same wall against where the counter was positioned when Bill returned his costume and found his mask missing. He was told he could return later and it needn't be for a costume. Entering Sharky's, he has in fact returned (in essence) only now it is to discover that the beautiful model (with whom he'd shared a masked kiss) was found overdosed in her apartment. The audience thinks murder but the inference is that the overdose may have instead been a suicide, just as the book makes it unclear whether the overdose was by suicide or was enforced. Amanada will be revealed to be the woman. She is the same one who overdosed in Victor's bathroom in which a bathtub was a central focus, standing prominently out beneath the painting of a pregnant woman.

In Barry Lyndon, Barry is caught having an affair. Later, when Lady Lyndon is in her bath, the following is being read to her.

"Les cœurs, l'un par l'autre attirés Se communiquent leur substance; Tels deux miroirs ardents, l'un à l'autre opposés ; Concentrent la lumière, et se la réfléchissent : Les rayons tour-à-tour recueillis... divisés, En se multipliant s’accroissent, s'embellissent ; Et d'autant plus actifs, qu'ils se sont plus croisés, Au même point se réunissent."

After this reading the pair are reunited with an apology on Barry's part, and a chaste yet soulful kiss.

The poem read to Lady Lyndon in her bath I think is significant. We have in it opposites, the thing and it's other in the mirror, crossing where they meet.

Ophelia, I think, ends up bringing in a Narcissus motif, and Narcissus' still waters in which he found himself are the same as the ritual aspect of the Dionysian mirror. On the wall opposite Ophelia at Sharky's is another Rossetti painting, this one of Astarte, in which she is bordered on either side by twin aspects facing one another. Bill's lost mask is depicted as a kind of image (mirror) of Bill when it takes his place on the pillow. The mask was supposedly modeled upon Ryan O'Neal in Barry Lyndon, and I can only think that it must be referring to the scene in the bathtub in which the opposites, as two mirrors, cross and reunite.

To understand the significance of Astarte one needs to read on Ulalume in Lolita. A person finds that without realizing it they have trod a path taken before to the tomb of a dead woman. Deja vu. Kubrick and Nabokov made much of the turn-around of mid/dim in the poem.

We know in 2001 the first time we see a flip reversal (in that film) is the horizontal flip of the landscape scene when we first ever see the monolith. Then at the end of the film, as the camera draws in on the monolith, we see the room on either side resolving into a mirror image, one of the other. The monolith is the point between, the line where they meet. And I think that Kubrick's single point perspective shots all refer to this. In 2001 it is a place of death and rebirth.

How does "...the last game..." scene play into this, preceding it? Where we have a crossing of opposites or reflections there will be a blending, and I think we have this expressed in "the last game" preceding the bathtub scene.

I've mentioned before that I think Runt, who is presumably gay, somewhat serves as a double for Lady Lyndon. They are very much alike in their deportment and even in their elongated, lean features. They are playing cards with two women whose hairstyles are exactly alike as are their dresses. But wait. Are they two women? They appear to be so but I don't believe they are. I think the woman on screen left is a man. We have an expression of the man/woman, the hermaphroditic. They symbolically express the coupling that is Lady Lyndon and Runt. When does Lady Lyndon attempt suicide? After Bryan's death? No, it is after Runt is removed from her, Barry Lyndon's mother declaring him to be the cause of her affliction.

Which takes us back to the two gay men in the lake and Barry stealing Fakenham's identity. The two men in the lake were almost as mirror images of one another, and, yes, they are gay, but in the movie they seem to end up being a blend of the feminine and masculine and thus a kind of hermaphroditic expression.

The two men so resemble one another from afar that this may be where, as far as the film is concerned, Barry gets the idea to steal Fakenham's clothing and proceed as his counterfeit double.

What happens when Barry, in the guise of Fakenham, meets Lischen? He asks if her child is a boy or a girl. He is unable to tell which the infant is.

But let us look again at Ophelia, who does have significance to Barry Lyndon as Bullingdon in the novel was said to have quoted lengthy passages of Hamlet to his mother.

With Ophelia we have a person who becomes a perfect mirror, as expressed by the messenger.

Her speech is nothing,

Yet the unshaped use of it doth move

The hearers to collection. They aim at it,

And botch the words up fit to their own thoughts,

Which, as her winks and nods and gestures yield them,

Indeed would make one think there might be thought,

Though nothing sure, yet much unhappily.

Unable to divine what her intent is, meaning is supplied by others. She becomes a reflection. Lady Lyndon is so silent and reserved that she is often the same, we are unable to divine her deeper thoughts, but so too with Barry.

The "deranged" Pierrette in Eyes Wide Shut becomes an Ophelia, standing where the painting of Ophelia will later be, and as I've earlier noted her expression is a perfect riddle, so much so that her blankness almost mocks in its obscurity. And, oddly enough, I think she is intended to be a deep expression of Bill. The truth of him, whatever that may be.

529 LS across the lake of the residence. (1:53:07)

Toward end of 9th measure of the Movement we switch scenes.

530 Barry seated and speaking with tailors as he is being dressed. (1:53:16)

Last note of the 10th measure plays and the music ends.

TAILOR:

This coat is made of the finest velvet, all cunningly worked, as you see, with silver thread.

531 Lady Lyndon enters with the infant and Lord Bullingdon. (1:53:23)

TAILOR: No finer velvet has ever been woven, and you will see none better anywhere.

LADY LYNDON:

Pardon me, gentlemen. Good morning, dearest.

She kisses Barry.

BARRY: Good morning.

532 From Barry's left, Lady Lyndon and others. (1:53:43)

LADY LYNDON:

We're taking the children for a ride to the village. We'll be back for tea.

BARRY: Well, have a nice time. I'll see you then. Goodbye, little Bryan.

He kisses the baby.

533 MCU Lord Bullingdon as Barry reaches for him. (1:53:54)

BARRY: Lord Bullingdon.

Take good care of your mother.

He kisses him.

534 CU of Barry from Lord Bullingdon's right. (1:54:03)

BARRY:

Come now, give your father a proper kiss.

535 CU of Lord Bullingdon refusing to reciprocate with a kiss as Barry kisses him again. A bell rings in the background. (1:54:08)

536 CU of Barry. (1:54:16)

LADY LYNDON:

Lord Bullingdon...

537 CU of Lord Bullingdon. (1:54:21)

LADY LYNDON: Is that the way to behave

to your father?

538 CU of Lady Lyndon. (1:54:25)

LADY LYNDON: Lord Bullingdon,

have you lost your tongue?

539 CU of Lord Bullingdon. (1:54:28)

LORD BULLINGDON:

My father was Sir Charles Lyndon. I have not forgotten him, if others have.

The Lady slaps him.

540 CU of Lady Lyndon. (1:54:37)

LADY LYNDON:

Lord Bullingdon, you have insulted your father!

541 Cu of Lord Bullingdon. (1:54:41)

LORD BULLINGDON:

Madam, you have insulted my father.

542 LS of the scene. (1:54:45)

BARRY:

Dearest, would you excuse Lord Bullingdon and me for a few minutes? We have something to discuss in private. Gentlemen.

543 MS of Lady Bullingdon. (1:55:03)

529 |

530 |

531 |

532 |

533 |

534 |

535 |

536 |

537 |

538 |

539 |

540 |

541 |

542 |

543 | |

544 Lord Bullingdon leans over a table as Barry whips him. (1:55:08)

BARRY:

One.

Two. Three. Four. Five. Six.

545 MS of Lord Bullingdon. (1:55:38)

BARRY: Lord Bullingdon, I have always been willing to live with you on terms of friendship, but be clear about one thing...

546 MS of Barry. (1:55:47)

BARRY: ...as men serve me, I serve them. I've never laid a cane on the back of a Lord before, but, if you force me to, I shall speedily become used to the practice.

547 Return to Lord Bullingdon. (1:55:58)

BARRY: Do you have anything to say for yourself?

LORD BULLINGDON:

No.

548 MS Barry. (1:56:07)

BARRY:

You may go.

NARRATION (as Bullingdon exits left and Barry walks off screen right):

Barry had believed, and not without some reason, that it had been a declaration of war against him by Bullingdon from the start, and that the evil consequences which ensued were entirely of Bullingdon's creating.

545 |

546 |

547 |

548 |

Yes, many extended quotations, because I love the book and because I think it's important to give sections from the novel that influence the film but aren't expressed in it.

We have in this passage the jealousy over the governess and the fight with Bullingdon in which he refused to acknowledge Barry as a father, occurring when he was sixteen.

Whilst these improvements were going on in my estates,—my house, from an antique Norman castle, being changed to an elegant Greek temple, or palace—my gardens and woods losing their rustic appearance to be adapted to the most genteel French style—my child growing up at his mother's knees, and my influence in the country increasing,—it must not be imagined that I stayed in Devonshire all this while, and that I neglected to make visits to London, and my various estates in England and Ireland...

And as my Lord Bullingdon was by this time grown excessively tall and troublesome, I determined to leave him under the care of a proper governor in Ireland, with Mrs. Brady and her six daughters to take care of him; and he was welcome to fall in love with all the old ladies if he were so minded, and thereby imitate his stepfather's example. When tired of Castle Lyndon, his Lordship was at liberty to go and reside at my house with my mamma; but there was no love lost between him and her, and, on account of my son Bryan, I think she hated him as cordially as ever I myself could possibly do.

One of the main causes of expense which this ambition of mine entailed upon me was the fitting out and arming a company of infantry from the Castle Lyndon and Hackton estates in Ireland, which I offered to my gracious Sovereign for the campaign against the American rebels. These troops, superbly equipped and clothed, were embarked at Portsmouth in the year 1778; and the patriotism of the gentleman who had raised them was so acceptable at Court, that, on being presented by my Lord North, His Majesty condescended to notice me particularly, and said, 'That's right, Mr. Lyndon, raise another company; and go with them, too!' But this was by no means, as the reader may suppose, to my notions. A man with thirty thousand pounds per annum is a fool to risk his life like a common beggar: and on this account I have always admired the conduct of my friend Jack Bolter, who had been a most active and resolute cornet of horse, and, as such, engaged in every scrape and skirmish which could fall to his lot; but just before the battle of Minden he received news that his uncle, the great army contractor, was dead, and had left him five thousand per annum. Jack that instant applied for leave; and, as it was refused him on the eve of a general action, my gentleman took it, and never fired a pistol again: except against an officer who questioned his courage, and whom he winged in such a cool and determined manner, as showed all the world that it was from prudence and a desire of enjoying his money, not from cowardice, that he quitted the profession of arms.

When this Hackton company was raised, my stepson, who was now sixteen years of age, was most eager to be allowed to join it, and I would have gladly consented to have been rid of the young man; but his guardian, Lord Tiptoff, who thwarted me in everything, refused his permission, and the lad's military inclinations were balked. If he could have gone on the expedition, and a rebel rifle had put an end to him, I believe, to tell the truth, I should not have been grieved over-much; and I should have had the pleasure of seeing my other son the heir to the estate which his father had won with so much pains.

The education of this young nobleman had been, I confess, some of the loosest; and perhaps the truth is, I DID neglect the brat. He was of so wild, savage, and insubordinate a nature, that I never had the least regard for him; and before me and his mother, at least, was so moody and dull, that I thought instruction thrown away upon him, and left him for the most part to shift for himself. For two whole years he remained in Ireland away from us; and when in England, we kept him mainly at Hackton, never caring to have the uncouth ungainly lad in the genteel company in the capital in which we naturally mingled. My own poor boy, on the contrary, was the most polite and engaging child ever seen: it was a pleasure to treat him with kindness and distinction; and before he was five years old, the little fellow was the pink of fashion, beauty, and good breeding.

In fact he could not have been otherwise, with the care both his parents bestowed upon him, and the attentions that were lavished upon him in every way. When he was four years old, I quarrelled with the English nurse who had attended upon him, and about whom my wife had been so jealous, and procured for him a French gouvernante, who had lived with families of the first quality in Paris; and who, of course, must set my Lady Lyndon jealous too. Under the care of this young woman my little rogue learned to chatter French most charmingly. It would have done your heart good to hear the dear rascal swear Mort de ma vie! and to see him stamp his little foot, and send the manants and canaille of the domestics to the trente mille diables. He was precocious in all things: at a very early age he would mimic everybody; at five, he would sit at table, and drink his glass of champagne with the best of us; and his nurse would teach him little French catches, and the last Parisian songs of Vade and Collard,—pretty songs they were too; and would make such of his hearers as understood French burst with laughing, and, I promise you, scandalise some of the old dowagers who were admitted into the society of his mamma: not that there were many of them; for I did not encourage the visits of what you call respectable people to Lady Lyndon. They are sad spoilers of sport,—tale-bearers, envious narrow-minded people; making mischief between man and wife. Whenever any of these grave personages in hoops and high heels used to make their appearance at Hackton, or in Berkeley Square, it was my chief pleasure to frighten them off; and I would make my little Bryan dance, sing, and play the diable a quatre, and aid him myself, so as to scare the old frumps.

...

I should now speak of my other son, at least my Lady Lyndon's: I mean the Viscount Bullingdon. I kept him in Ireland for some years, under the guardianship of my mother, whom I had installed at Castle Lyndon; and great, I promise you, was her state in that occupation, and prodigious the good soul's splendour and haughty bearing. With all her oddities, the Castle Lyndon estate was the best managed of all our possessions; the rents were excellently paid, the charges of getting them in smaller than they would have been under the management of any steward. It was astonishing what small expenses the good widow incurred; although she kept up the dignity of the TWO families, as she would say. She had a set of domestics to attend upon the young lord; she never went out herself but in an old gilt coach and six; the house was kept clean and tight; the furniture and gardens in the best repair; and, in our occasional visits to Ireland, we never found any house we visited in such good condition as our own. There were a score of ready serving-lasses, and half as many trim men about the castle; and everything in as fine condition as the best housekeeper could make it. All this she did with scarcely any charges to us: for she fed sheep and cattle in the parks, and made a handsome profit of them at Ballinasloe; she supplied I don't know how many towns with butter and bacon; and the fruit and vegetables from the gardens of Castle Lyndon got the highest prices in Dublin market. She had no waste in the kitchen, as there used to be in most of our Irish houses; and there was no consumption of liquor in the cellars, for the old lady drank water, and saw little or no company...

Young Bullingdon, however, was almost the only person with whom she was concerned that my mother could not keep in order. The accounts she sent me of him at first were such as gave my paternal heart considerable pain. He rejected all regularity and authority. He would absent himself for weeks from the house on sporting or other expeditions. He was when at home silent and queer, refusing to make my mother's game at piquet of evenings, but plunging into all sorts of musty old books, with which he muddled his brains; more at ease laughing and chatting with the pipers and maids in the servants' hall, than with the gentry in the drawing-room; always cutting jibes and jokes at Mrs. Barry, at which she (who was rather a slow woman at repartee) would chafe violently: in fact, leading a life of insubordination and scandal. And, to crown all, the young scapegrace took to frequenting the society of the Romish priest of the parish—a threadbare rogue, from some Popish seminary in France or Spain—rather than the company of the vicar of Castle Lyndon, a gentleman of Trinity, who kept his hounds and drank his two bottles a day.

Regard for the lad's religion made me not hesitate then how I should act towards him. If I have any principle which has guided me through life, it has been respect for the Establishment, and a hearty scorn and abhorrence of all other forms of belief. I therefore sent my French body-servant, in the year 17—, to Dublin with a commission to bring the young reprobate over; and the report brought to me was that he had passed the whole of the last night of his stay in Ireland with his Popish friend at the mass-house; that he and my mother had a violent quarrel on the very last day; that, on the contrary, he kissed Biddy and Dosy, her two nieces, who seemed very sorry that he should go; and that being pressed to go and visit the rector, he absolutely refused, saying he was a wicked old Pharisee, inside whose doors he would never set his foot. The doctor wrote me a letter, warning me against the deplorable errors of this young imp of perdition, as he called him; and I could see that there was no love lost between them. But it appeared that, if not agreeable to the gentry of the country, young Bullingdon had a huge popularity among the common people. There was a regular crowd weeping round the gate when his coach took its departure. Scores of the ignorant savage wretches ran for miles along by the side of the chariot; and some went even so far as to steal away before his departure, and appear at the Pigeon-House at Dublin to bid him a last farewell. It was with considerable difficulty that some of these people could be kept from secreting themselves in the vessel, and accompanying their young lord to England.

To do the young scoundrel justice, when he came among us, he was a manly noble-looking lad, and everything in his bearing and appearance betokened the high blood from which he came. He was the very portrait of some of the dark cavaliers of the Lyndon race, whose pictures hung in the gallery at Hackton: where the lad was fond of spending the chief part of his time, occupied with the musty old books which he took out of the library, and which I hate to see a young man of spirit poring over. Always in my company he preserved the most rigid silence, and a haughty scornful demeanour; which was so much the more disagreeable because there was nothing in his behaviour I could actually take hold of to find fault with: although his whole conduct was insolent and supercilious to the highest degree. His mother was very much agitated at receiving him on his arrival; if he felt any such agitation he certainly did not show it. He made her a very low and formal bow when he kissed her hand; and, when I held out mine, put both his hands behind his back, stared me full in the face, and bent his head, saying, 'Mr. Barry Lyndon, I believe;' turned on his heel, and began talking about the state of the weather to his mother, whom he always styled 'Your Ladyship.' She was angry at this pert bearing, and, when they were alone, rebuked him sharply for not shaking hands with his father.

'My father, madam?' said he; 'surely you mistake. My father was the Right Honourable Sir Charles Lyndon. I at least have not forgotten him, if others have.' It was a declaration of war to me, as I saw at once; though I declare I was willing enough to have received the boy well on his coming amongst us, and to have lived with him on terms of friendliness. But as men serve me I serve them. Who can blame me for my after-quarrels with this young reprobate, or lay upon my shoulders the evils which afterwards befell? Perhaps I lost my temper, and my subsequent treatment of him WAS hard. But it was he began the quarrel, and not I; and the evil consequences which ensued were entirely of his creating.

In the book, the fight with Bullingdon concerns not a kiss, but Bullingdon's refusal to shake Barry's hand and acknowledge him as his father. By having this fight, in the film, when Bullingdon is much younger, is to stress the unrelenting and drawn-out animosity that Bullingdon has had for Barry from when he wed Lady Lyndon. We also have here the root of Bullingdon's emotional struggle over his mother, his affection for her and his ire for her over Lady Lyndon siding with Barry and insisting that he behave contrary his feelings, not defending him against Barry, favoring Barry over him. He had taken her hand to comfort her, in the film, when they saw Barry with the governess. He had been loyal to her. She doesn't show loyalty to him in demanding that he kiss Barry when he has observed Barry's infidelity and cruelty. Bullingdon is not willing to forgive and accept, and it's easy to understand why.

One of the men in attendance here wears a turban that is either similar to or identical to one worn by a black servant in the Lord Ludd scene, worn also by the same servant when Lady Lyndon excuses herself from the gaming table to meet Barry outside. The black servant is mentioned also in the book. Why his distinctive headgear now appears on this gentlemen who is attempting to sell Barry a coat, I don't know. I doubt it is specific to identification of a certain kind of servanthood.

From the book:

...a tall negro fellow habited like a Turk, that used to wait upon me...

The actor selling the coat is the same actor who plays the "party" man with the split head in The Shining.

549 Zoom out from Lord Bullingdon holding his mother's hand, sitting on the lawn, to a view of the party of people. (1:56:46)

Schubert's German Dance No. 1 in C Major begins. A beautifully light and happy piece, full or hope.

MAGICIAN (off screen): I shall make you into a real magician now, Bryan. I shall show you the knot that never was...

NARRATION: As Bullingdon grew up to be a man, his hatred for Barry assumed an intensity equalled only by his increased devotion to his mother.

MAGICIAN: Very good, Bryan. A little bow. That's good.

All clap but for Bullingdon and Lady Lyndon who are holding hands.

550 3/4 LS of the stage from beyond the partiers. (1:56:56)

MAGICIAN: Will you put it on the table for me? Thank you very much, indeed.

NARRATION: For Bryan's eighth birthday...

MAGICIAN: ...my magic bag...

NARRATION: ...the local nobility, gentry and their children...

551 MS of Bryan on the stage with a magician. (1:57:06)

NARRATION: ... came to pay their respects.

The magician displays a blue bag with a white pom, pulling it inside out to show the black interior and that there is nothing in it, then produces a long streamer of knotted, colorful scarves. He then pulls a ball from behind Bryan's ear. He has Bryan bow.

MAGICIAN: The inside is quite empty. The outside is quite empty. Wave your hand over the top, Bryan. Is there anything there? Yes. Wonderful! Wonderful, colourful silk handkerchiefs! Take a bow, Bryan, you did that beautifully. Very good, indeed. Let's see if you have something behind your ear. Yes, you have.

552 Pan across the partiers from right to left, beginning with Runt. (1:57:37)

MAGICIAN (off screen): A little ball. Let's make it vanish. It's gone, Bryan. Here it is, here it is, behind my elbow.

All clap.

MAGICIAN: I want you to wave your hand over my green silk handkerchief and see whether we can produce a magic flower. I wonder if we can? There it comes. Look at that. We have the colours of the rainbow.

553 MCU of Bryan with the magician swirling colorful ribbong around him. (1:58:02)

MAGICIAN: There they are. You know all the colours of the rainbow produce but one colour, Bryan. Nothing in my magic cabinet. They produce the colour white.

He next shows Bryan an empty drawer. He closes it and opens it and we see a white rabbit.

MAGICIAN: And there is my own...

554 MCU of Barry's mother. (1:58:15)

MAGICIAN (off camera): ...beautiful white rabbit. Bryan, you have done very well. A little bow. That's right.

555 Zoom out from a MS of Bryan riding in a carriage pulled by two sheep. (1:58:26)

549 |

550 |

551 |

552 |

553 |

554 |

There is no such scene in the book.

Shot 550 of the magic show connects back with shots 251 and 281 from the regimental display. We have a same kind of interesting misdirection practiced here as in them. Just as there was a "false" Barry occupying the center in shots 251 and 261, while Barry was present but standing to the left screen, in shot 550, while Bryan is on the stage, we have a little boy with of similar build, with similar long blond hair, seated center screen as if in a place of honor. This boy will appear again, and the way he is positioned in the scene, we "feel" that he must be Bryan, though he is not. We haven't seen the eight year old Bryan up close on the stage yet, but when we do our minds return to this and picture this boy as being him, for he is in a place of central importance and distinctly resembles him. However, when we go to surrounding shots 549 and 552 we see how differently placed Barry's family is and has nothing to do with him. We know Bryan is on stage, and we know that the family would be directly in front of the stage. Peculiarly, if we look back at 549, we are seeing a grown Bullingdon sitting on the ground beside his mother. The way that he is seated low and center, attention is drawn to him. He becomes geographically confused, too, with the small boy in the center in shot 550. The "false" Bryan, who wears blue, and Bullingdon, who wears blue breeches, blend together.

This confusion returns us to shots 251 and 281. In shot 251 we see a man standing center in such a way that he has primary importance. In shot 281 we see that he is positioned to physically refer to Barry. I've written previously about their stances. How Barry has his leg positioned as was the other man's, and the way we do not see his hands, the way they are behind his back, ends up connecting him more to the central figure in shot 25 than if his hands were before him, for thus the central men in both shots 251 and 281 have their hands forearms concealed.

Further, they stand between two carriages and each have a girl standing beside them.

We expect Barry to be central, as he is shown in shot 281, pictured between the two carriages, but when we look back at shot 251 (and all other shots from this angle, for there are several) we realize that Barry is actually in the shot, standing next the left wagon, not center at all. It's an intentional misdirection.

Now we have it again here, with the misdirection absorbing Bullingdon into a double of Bryan. This appears to be the child who is walking alongside the carriage in which Bryan is riding in shot 550. They are the same size. They have the same haircut, the same bangs. The child walking alongside, banging the red drum, behaves much the same as Bryan.

That red drum he is banging also takes us back to the regimental display with its drummers standing opposite the civilians.

My feeling is that the center individual in shot 25, Barry off to the side, is supposed to be the audience as principal character in the story, their read of it, their emotional responses. It isn't Barry at all. He's an agent facilitating, and if you look at his role in the film you find that in a way the stories revolve much more around the people whom cross Barry's path. But the audience, as principal character, is aligned with Barry as indicated in shot 281.

The film now makes a shift and the principal character that the film is ostensibly about is no longer Barry at all, as observed in shots 549 and 550. Barry is not center. Bullingdon is center in shot 549, while in shot 550 it is Bryan and his double (as well as the magician). Who fuels the emotional content of the film from this point on? It's the children. Both Bryan and Bullingdon. Even after Bryan's death, the grief is about him, and Bullingdon enters soon enough again.

Who is the story about also fits in with the magician's stage, its cloudy heavens surrounded by horoscope symbols and myths, surmounted by the sun and above this a half diagram of a seeming other sun with what should be likely 8 planetary bodies around it but only showing 3 and halves of the 4th and 5th. But Neptune wouldn't be discovered until later so what are we looking at? Uranus wasn't discovered until 1781. Again, so what are we looking at? The only system I can think of this might begin to correspond to would be a qabalistic tree of life with 8 outer lying spheres and the two in the middle being Tiphareth and Yesod (which leaves out Da'ath which is hidden anyway), only here instead we have one and 1/2 suns. I'm sure there's a good esoteric description out there for what we're seeing but I've not come across anything yet. Or, we may have something corresponding to a 17th century Rosicrucian medal in which a cloudy center is circumscribed by Saturn, Venus, Jupiter, Mercury, Mars, the Moon, the Sun (seemingly) and a pentacle surmounting a cross or arrow. I don't know..

But the point is what we're seeing in the magician's backdrop is what amounts to an examination of what is the center of the cosmos. Around what does creation circulate, physically and/or spiritually, the clouds before which Bryan and the Magician stand representing the veils before the unknowable. In other words, where did humanity fit into the scheme of things?

The magician promises to make Bryan a real magician, one who shall know the knot that never was, and ends with a lesson on the rainbow, Isaac Newton's comprehension of all its colors resolving in the additive process into one, white.

556 LS of the mansion at sunset. (1:58:44)

557 MS of Bryan in bed, Barry and his mother sitting with him. (1:58:49)

BARRY: We crept up on their fort, and I jumped over the wall first. My fellows jumped after me. Oh, you should have seen the Frenchmen's faces when rampaging he-devils...

558 CU of Barry's mother. (1:59:00)

BARRY (off screen): ...sword and pistol, cut and thrust, pellmell came tumbling into their fort.

559 MS of Bryan and Barry from the side. (1:59:06)

BARRY: In three minutes we left as many Artillery men's heads as there were cannon balls. Later that day we were visited by our noble Prince Henry. "Who is the man who has done this?" I stepped forward. "How many heads was it," says he, "that you cut off? " "Nineteen," says I, "besides wounding several." Well, when he heard it, I'll be blessed if he didn't burst into tears.

560 CU of Bryan holding a lamb. (1:59:30)

BARRY (off screen): "Noble, noble fellow," he said. "Here is nineteen golden guineas for ya, one for each head that you cut off." Now, what do you think of that?

BRYAN: Were you allowed to keep the heads?

561 Return to shot 557. (1:59:42)

BARRY: No, the heads always become the property of the King.

BRYAN: Will you tell me another story?

BARRY: I'll tell you one tomorrow.

BRYAN: Will you play cards with me tomorrow?

BARRY: Of course I will. Now go to sleep.

They kiss and embrace.

BRYAN: Will you keep the candles lit?

BARRY'S MOTHER: Oh, now, Bryan, big boys don't sleep with the candles lit.

BRYAN: But I'm afraid of the dark.

BARRY'S MOTHER: But my darling, there's nothing to be afraid of.

BRYAN: But, I like it with the candles lit.

BARRY: It's all right, you can sleep with the candles lit. Thank you, Papa. Good night.

End the Schubert.

556 |

557 |

558 |

559 |

560 |

561 |

This scene doesn't exist in the book. We shall have an inversion later of this bed time story and Bryan's birthday party with Bryan's death, his request for this story preceding his death, in which he will be carried by the same carriage in which he rode at the end of his party. At the very end of shot 555, the birthday party seems to begin to be overcome with shadow, which may be the idea of the setting sun, but I think also is a premonition of the disastrous year ahead of them.

This bedtime story section shows how Mrs. Barry shames Bryan for his fear of the dark, rebuking him for not being a "big boy", whereas Barry will not. He's sympathetic. But Barry's mother has her own fears, next pressuring him to pursue lasting security for him and his son.

562 Zoom out from shot through the arch of a bridge of Bryan, Lady Lyndon, Runt and Lord Bullingdon in a small boat. (2:00:25)

BARRY'S MOTHER: Ah, Redmond! It's a blessing to see my darling boy attain a position I knew was his due.

563 Barry and his mother, MS from the side, beside a classical temple facsimile. (2:00:55>

BARRY'S MOTHER: And for which I pinched myself to educate him. Little Bryan is a darling boy and you live in great splendour.

564 CU of Barry's mother. (2:01:08)

BARRY'S MOTHER: Your lady wife knows she has a treasure she couldn't have had, had she taken a Duke to marry him. But, if one day she should tire of my wild Redmond and his old-fashioned lrish ways, or if she should die, what future would there be for my son, and my grandson?

565 MCU of Barry. (2:01:32)

BARRY'S MOTHER (off screen): You have not a penny of your own and cannot transact any business without her signature. Upon her death the entire estate would go to...

566 CU of Barry's mother. (2:01:45)

BARRY'S MOTHER: ...young Bullingdon, who bears you little affection. You could be penniless tomorrow, and darling Bryan at the mercy of his stepbrother.

567 MS from the side of Barry and his mother. (2:02:01)

BARRY'S MOTHER: Shall I tell you something? There is only one way for you and your son to have real security. You must obtain a title. I shall not rest until I see you Lord Lyndon. You have important friends. They can tell you how these things are done. For money, well-timed and properly applied, can accomplish anything.

562 |

563 |

564 |

565 |

566 |

567 |

Thus does Barry begin to wreck Lyndon's family fortune, urged on here by his mother, who Lady Lyndon intensely dislikes in the book and calls her a she dragon.

I determined to endow my darling boy Bryan with a property, and to this end cut down twelve thousand pounds' worth of timber on Lady Lyndon's Yorkshire and Irish estates: at which proceeding Bullingdon's guardian, Tiptoff, cried out, as usual, and swore I had no right to touch a stick of the trees; but down they went; and I commissioned my mother to repurchase the ancient lands of Ballybarry and Barryogue, which had once formed part of the immense possessions of my house. These she bought back with excellent prudence and extreme joy; for her heart was gladdened at the idea that a son was born to my name, and with the notion of my magnificent fortunes.

To say truth, I was rather afraid, now that I lived in a very different sphere from that in which she was accustomed to move, lest she should come to pay me a visit, and astonish my English friends by her bragging and her brogue, her rouge and her old hoops and furbelows of the time of George II.: in which she had figured advantageously in her youth, and which she still fondly thought to be at the height of the fashion. So I wrote to her, putting off her visit; begging her to visit us when the left wing of the castle was finished, or the stables built, and so forth. There was no need of such precaution. 'A hint's enough for me, Redmond,' the old lady would reply. 'I am not coming to disturb you among your great English friends with my old-fashioned Irish ways. It's a blessing to me to think that my darling boy has attained the position which I always knew was his due, and for which I pinched myself to educate him. You must bring me the little Bryan, that his grandmother may kiss him, one day. Present my respectful blessing to her Ladyship his mamma. Tell her she has got a treasure in her husband, which she couldn't have had had she taken a duke to marry her; and that the Barrys and the Bradys, though without titles, have the best of blood in their veins. I shall never rest until I see you Earl of Ballybarry, and my grandson Lord Viscount Barryogue.'

How singular it was that the very same ideas should be passing in my mother's mind and my own! The very title she had pitched upon had also been selected (naturally enough) by me; and I don't mind confessing that I had filled a dozen sheets of paper with my signature, under the names of Ballybarry and Barryogue, and had determined with my usual impetuosity to carry my point. My mother went and established herself at Ballybarry, living with the priest there until a tenement could be erected, and dating from 'Ballybarry Castle;' which, you may be sure, I gave out to be a place of no small importance. I had a plan of the estate in my study, both at Hackton and in Berkeley Square, and the plans of the elevation of Ballybarry Castle, the ancestral residence of Barry Lyndon, Esq., with the projected improvements, in which the castle was represented as about the size of Windsor, with more ornaments to the architecture; and eight hundred acres of bog falling in handy, I purchased them at three pounds an acre, so that my estate upon the map looked to be no insignificant one. [Footnote: On the strength of this estate, and pledging his honour that it was not mortgaged, Mr. Barry Lyndon borrowed L17,000 in the year 1786, from young Captain Pigeon, the city merchant's son, who had just come in for his property. At for the Polwellan estate and mines, 'the cause of endless litigation,' it must be owned that our hero purchased them; but he never paid more than the first L5000 of the purchase-money. Hence the litigation of which he complains, and the famous Chancery suit of 'Trecothick v. Lyndon,' in which Mr. John Scott greatly distinguished himself.-ED.]

I also in this year made arrangements for purchasing the Polwellan estate and mines in Cornwall from Sir John Trecothick, for L70,000—an imprudent bargain, which was afterwards the cause to me of much dispute and litigation. The troubles of property, the rascality of agents, the quibbles of lawyers, are endless. Humble people envy us great men, and fancy that our lives are all pleasure. Many a time in the course of my prosperity I have sighed for the days of my meanest fortune, and envied the boon companions at my table, with no clothes to their backs but such as my credit supplied them, without a guinea but what came from my pocket; but without one of the harassing cares and responsibilities which are the dismal adjuncts of great rank and property.

I did little more than make my appearance, and assume the command of my estates, in the kingdom of Ireland; rewarding generously those persons who had been kind to me in my former adversities, and taking my fitting place among the aristocracy of the land. But, in truth, I had small inducements to remain in it after having tasted of the genteeler and more complete pleasures of English and Continental life; and we passed our summers at Buxton, Bath, and Harrogate, while Hackton Castle was being beautified in the elegant manner already described by me, and the season at our mansion in Berkeley Square.

I've spoken before of how Kubrick has in all his films the journey to the underworld. (The Shining is all journey into the underworld.) This scene is at Stourhead. Well known in the 18th century would have been Stourhead lake's environ representing Aeneas' journey into the underworld.

From Wikipedia:

The lake at Stourhead is artificially created. Following a path around the lake is meant to evoke a journey similar to that of Aeneas's descent in to the underworld.[14] In addition to Greek mythology, the layout is evocative of the "genius of the place", a concept made famous by Alexander Pope. Buildings and monuments are erected in remembrance of family and local history. Henry Hoare was a collector of art– one of his pieces was Claude Lorrain's Aeneas at Delos, which is thought to have inspired the pictorial design of the gardens.[14] Passages telling of Aeneas's journey are quoted in the temples surrounding the lake.

Monuments are used to frame one another; for example the Pantheon designed by Flitcroft entices the visitor over, but once reached, views from the opposite shore of the lake beckon.[15] The use of the sunken path allows the landscape to continue on into neighbouring landscapes, allowing the viewer to contemplate all the surrounding panorama. The Pantheon was thought to be the most important visual feature of the gardens. It appears in many pieces of artwork owned by Hoare, depicting Aeneas's travels.[16] The plantings in the garden were arranged in a manner that would evoke different moods, drawing visitors through realms of thought.[15] According to Henry Hoare, 'The greens should be ranged together in large masses as the shades are in painting: to contrast the dark masses with the light ones, and to relieve each dark mass itself with little sprinklings of lighter greens here and there.'[17]

The website, The Garden Visitor, represents it as follows: