In which James Mason and Shelley Winters beat Lucy and Dezi into the ground with baseball bats, then hop up and down upon their comedic graves

Clare Quilty, the chair

That I’d been directly immersed into the chaos of someone’s revealed dream is how I felt the first time I watched Humbert Humbert (James Mason) enter the black-and-white baroque/rococo, bric-a-brac, moving-day set of Quilty’s mansion, through which Humbert stumbles in dumb, amazed horror, hell as a puzzle where all the pieces have been retained but splintered so fine that to find a proper order is beyond the mind’s ability to comprehend what was once object or shadow play. What manner of disorder is this? Where have all the partyers gone, for there must have been a number of them. And the white sheets draped over the furniture wonder how long since they left, and when will they be called out of storage to play again in another Kubrick film? A brittle and stagnant energy of old offered up as novel, each time with a different twist of perception, so that when the layers archeologically pancake together in the sediment of time there’s no distinguishing between them. Harp and harpsichord tinklings hint at heaven subverted with the orgies of rebellious angels.

“Quilty, Quilty!” Mason calls, and eventually one of the pieces of furniture answers, stirs beneath its shroud, and there separates from a chair a man who drapes the shhet over his pajamas in the manner of a Roman toga, the sleeper awakened. Is this Quilty? “No, I’m Spartacus,” he answers. “You come to free the slaves or something?” Though Mason clearly intends to kill him, Quilty’s apparently random, rampant behavior seems careless or oblivious of eminent danger, as if he doesn’t quite understand that it’s all not a game, that to Mason this is real, and in that way maybe Mason’s actions are as illogical to Quilty as his are to Mason. Genius ping-pongs the mundane into the realm of the fantastic, the camera frame denying we are out of bounds.

“Quilty, I want you to concentrate, you’re going to die. Try to understand what is happening to you,” Humbert Humbert encourages.

What Humbert Humbert wants is for Quilty (Peter Sellers) to congeal into a single coherent presence. But as the man of a thousand voices, Clare Quilty continually morphs, infusing each object he touches with his sensibility, vivifying it with his multiple lives. He is less Mason’s conscience than a continually evolving, renewing process of guilt (indeed, guilty quilty) doggedly persistent by reason of Humbert Humbert’s vigilante justice. Clare Quilty is light twisted and turned Lilith-like toward the dark. His head revolves and here is yet another face of guilt, all that exists tainted with Humbert Humbert’s obsession, with himself. And so can Quilty be Kubrick’s Spartacus, and also Davey, the boxer from Killer’s Kiss when he pulls on boxing mitts mirroring Humbert’s action of slipping on white gloves, Kubrick’s inspirational geniuses consistent behind all its various masks. As Quilty asserts, “I’m a playwright. You know, I know all about this sort of tragedy and comedy and fantasy and everything. I’ve got fifty-two successful scenarios to my credit, added to which my father’s a policeman.”

Up the mansion’s staircase Humbert Humbert follows Quilty, where he finally shoots him in the leg, rendering his lower body useless. He can only slither-pull himself along now, still taunting, “You can move in. I’ve got some nice friends, you know, who could come and keep you company here. You could use them as pieces of furniture. This one guy looks just like a bookcase.” He could fix it up for Humbert to attend executions, because Humbert likes watching, doesn’t he. Watching! As Quilty pulls himself behind a Thomas Gainsborough-style painting of a young, blond woman in a wide-brimmed black hat, he calls out, “Not many people know that the chair is painted yellow. You’d be the only guy in the know.”

Bang bang bang bang bang, Humbert riddles the portrait with bullets, Quilty crying out, “That hurts,” his hand sliding up along the frame of the picture behind which he is hidden, yet another face. Mercurial, hermaphroditic, Clare Quilty, framed, becoming now both Lolita as well as her mother, Charlotte. It was Charlotte’s first husband, the man of integrity, who purchased the gun when he discovered he was ill (“I’m a sick man,” Quilty earlier declared). It was Charlotte who declared if she found out Humbert didn’t believe in God, she’d have to kill herself. (“The question is, does God believe in me?” Humbert had said.) And contemplating the murder of Charlotte when he learned she intended to send little beloved Lolita away a fantasy of murder camouflaged as an accident, a playful burglar/intruder prank gone all wrong) it was Humbert who had thought to himself that no, he could never do that, could never use the gun on Charlotte. “I just couldn’t make myself do it! The scream grew more and more remote, and I realized the melancholy fact that neither tomorrow nor Friday nor any other day or night could I make myself put her to death.” But the fact is he already has because she has never been real to him, never alive to him, never an “other.” Because everything that is is Humbert looking back at himself. There is nothing which has any life apart from himself.

Into the New World, an Old World refugee

Humbert, the Old World European, never could fit into the youthful New World of America. Whatever haven it’s said he was looking for when he arrived, we don’t know, or what he was fleeing, just that he came and his coming took him first to the quaint, New England town of Ramsdale, though his destination was to be Beardsley College in Ohio where he’d garnered a lectureship.

How innocent and naive does this New World seem to disdainful Humbert, a white picket fence surrounding Charlotte Haze’s tidy, white wood house which aches for a border to replace the widow’s dead husband. But Charlotte (Shelley Winters) is needy all over. She wants not to be looked down on, to be the crass, country bumpkin to the city mouse, Charlotte insisting she and her friends are intellectually progressive, her house appointed here and there with primitive artifacts (a sculpted African head) intended to speak to how progressive progressive is in reclaiming the wisdom of the primal rather than scorning it.

She is New World innocence idolizing the old which claims cultural superiority, yet pulling a higher rank by way of New being Modern, “The bathroom’s back here, right next door. Well, we still have that good old-fashioned quaint plumbing. It should appeal to a European.”

Progressing to her bedroom (yes, why don’t you come into my bedroom and see my art) she even has reproductions. A fake Monet! And money. A well-set widow. Humbert was divorced In Paris? “You know, Monsieur, I really believe that it’s only in the romance languages that one is able to relate in a mature fashion. In fact, I remember when the late Mr. Haze–yes, he’s passed on–but when we were on our honeymoon abroad, I knew that I’d never felt married until I’d had myself addressed as senora.”

Still, Charlotte and her friends are youth all grown up physically, (“Kids,” they continually refer to themselves) but emotional development lagging far behind. Charlotte in that regard isn’t much older than Lolita, and despises the neediness of her child for conflicting with her own needs.

Continuing to sell herself, Charlotte attempts to win Humbert’s stomach with talk of her prize pastries, but Humbert, repelled, hints he’s not interested by asking for her phone number so he may call after thinking things over. Charlotte’s number? 1776. “The Declaration of Independence,” Humbert jokes. Click click goes Charlotte’s mind. How to get Humbert to stay. How not to lose him?

There’s the garden with her prize flowers. Her yellow roses…

There’s Lolita. “Diminutive for Delores, the tears, the roses,” Quilty will later say.

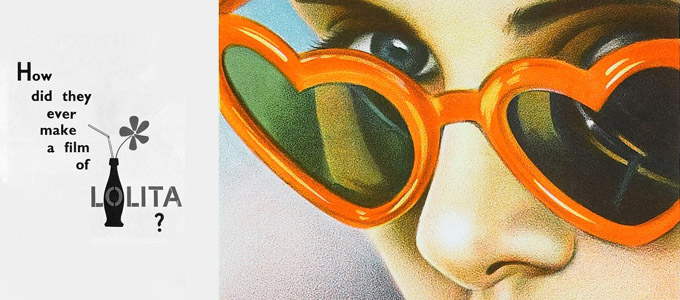

Lolita. In the garden, she suns herself in her two piece bathing suit, eyes hidden behind sunglasses, head topped by a massive sombrero-type hat feathery-fringed, which recalls a painting of a Mexican sleeping beneath his sombrero we’d earlier encountered upstairs, an unframed painting (recollect the framed Gainsborough-styled woman in her great hat) Charlotte obviously found an embarrassment, saying she had told Lolita to keep it in her room. It was in Mexico, not Spain, where Charlotte had heard herself called senora. In the not so distant future, it’s to Mexico where Humbert will seek to flee with Lolita (played by Sue Lyon), where they will leave their hunters behind, as if everything, even pedophilia, is ok in Mexico. And it’s to New Mexico where Lolita will instead escape, with Clare Quilty, to his arty little dude ranch.

Is Charlotte oblivious to Lolita as the selling point? Or does she, deep down, understand exactly what she’s doing, proferring dainty Lolita as another of her prize attractions? “I could offer you a comfortable home, a sunny garden, a congenial atmosphere, my cherry pies.”

The garden has a new appreciator, but, definitely, the cherry pies close the deal.

The Monster emerges

“Quilty!” Humbert had called, and the chair had stirred to life, Quilty emerging from beneath its shroud. At a drive-in theater, “The Curse of Frankenstein”startles, mummy-bandages unwound to reveal a monster’s grotesque visage. Humbert is bookended by Charlotte and Lolita. Lolita, who has been without a father for seven years, grabs Humbert’s leg. Charlotte, who has been without a husband these seven years, grabs his other leg. Whose hand does Humbert’s grasp? Guess.

“You’re going to take my Queen,” Charlotte complains when, playing chess with Humbert, Lolita wanders in for her nighty-night kiss from both mom and prospective new pop. “That is my intention,” says Humbert.

The great partner swap

At the Christmas dance in Eyes Wide Shut Nicole Kidman is introduced to the notion that in the old days the reason a woman married was so she could thus, no longer a virgin, bed those she really wanted.

“Mind if I dance with your girl? We could, um, sort of swap partners,” says John Farlow (Jerry Stovin) to Humbert, leaving him to sit it out with wife Jean Farlow (Diana Decker) at the Ramsdale High School Summer Dance.

In Lolita the prospect of the great partner swap is given as property of the 60’s revolution, but there is more to it than that. “Tonight’s the night,” Charlotte says. The night for what? It’s worrisome for Humbert. Will Lolita be defoliated by inept, youthful exploration at an after-dance party over at Mona Farlow’s? And worrisome for Humbert that an occasion for Lolita’s freedom to explore will be also Charlotte’s hope to propose (yes) teach, you know, Humbert some of the newer “dance steps.”

Humbert doesn’t dance. Humbert, in his white dinner jacket, certainly, vainly sees himself as the desirable sophisticate, even the bronzed god and boy toy he later accuses Charlotte of turning him into. But Humbert doesn’t dance, whereas cool Clare Quilty does. The school’s gym becomes the stage for Clare Quilty and his dark beatnik in black, serpentine-braceleted, dispassionately-intense female companion (Marianne Stone). “I adored his play, The Lady who Loved Lightning,” Jean says. All the girls are crazy for Clare Quilty. Charlotte as well. She breaks in upon Clare’s too cool partnership with Ms. Dark and Brooding, and seems not to notice Clare’s repulsion. Charlotte bubbles and blathers, “I’ll never forget that intellectually stimulating talk that you gave to our club.” Later, she whisperingly reminds Quilty of what they did that afternoon which changed her life. “And afterwards I showed you my garden.”

The tears, the roses. Lolita.

All the while the Woman in Black stands with her back to Charlotte, and Charlotte hardly seems to notice this as well. For her, the Woman in Black may as well be invisible. She simply doesn’t exist.

Back at the house, the sex-starved Mrs. Haze changes into cozy leopard print, the better to stalk Humbert. But the evening’s entertainment is cut short when Lo returns home early from the overnight party, which sets the bell tolling for Charlotte. For had Lo perhaps not returned home early, she might not have so infuriated Charlotte as to send her off to Camp Climax with Mona Farlow. Camp Climax, where Lolita will be initiated into the “game” by Charles, and while they’re at it, Humbert and the new Mrs. Charlotte Humbert will be busily celebrating their honeymoon.

So it goes for Humbert that to bed who he would really want, he must first be married.

And he will cry, oh, how he will cry.

Before Lo goes, however, Lo happens upon Humbert writing in his diary in the miniscule kind of handwriting only a “loving wife” would be able to decipher. Oh, no, it’s poetry, Humbert says, then will read to her from one of his favorites, Edgar Allen Poe, who happened also to be a nymph lover.

It was night in the lonesome October

Of my most immemorial year:

It was hard by the dim lake of Auber,

In the misty mid region of Weir”

Humbert points out how Poe takes a word like dim in one line and twists it….ooolaloooo….

To which lovely, lyrical, lilting Lo, Lola, Lolita, responds, “I think it’s corny.”

“What drives me insane is the twofold nature of this nymphet, a veteran nymphet perhaps, this mixture in my Lolita of tender, dreamy childishness and a kind of eerie vulgarity,” is what Humbert had written in his diary. The description fits mother Charlotte to a T.

Don’t forget me

To Camp Climax goes Lolita, the place of little deaths. So this then is goodbye, Lo and Humbert say to each other. And Lolita asks him to not forget her. Then, Lo gone, onto the pillow of Lo’s bed dissolves wretched Humbert, heartbroken. One of these passionate, emotional fellows, he tries to hide his tears when the maid, Louise, brings him a note big Charlotte left for him. On Lo’s bed, surrounded by photos of stars papering the walls, a TOKYO poster over his head, a cigarette ad for Clare Quilty at his right, Humbert again dissolves, this time into hysterical hilarity as he reads Charlotte begging the lodger to leave, be gone, departez, and that if he is there when she returns she will know he wants her as much as she wants him, to be forever mated, and he a father to her daughter.

Of course, once they are married, Charlotte is the kind of woman who insists there be no secrets between them. She wants to know all about the women in his life, certain he has not told her of everyone, then consoles herself with the knowledge the others were profane loves whereas their love is sacred. He brings out the pagan in her.

Charlotte, we become increasingly aware, is religious in a decidedly dedicated way. Yes, there was the portrait of her dead husband, the soul of integrity, hung on the wall above her icons of the Virgin, before which were set Harold’s ashes in a large urn. And, yes, Charlotte had said she had prayed at church, to God, to divine what to do about Humbert (the note she left for him, telling him to scram, beat it). But now she reveals to Humbert how she must commit suicide if she discovers he doesn’t believe in God, showing him Harold’s gun, which she calls the Sacred Weapon. He never even had a chance to use it before being admitted to the hospital. And now she wants Lolita to have a strict religious education, to send her away for it and convert her room into a guest room, a room for someone like a French maid.

“Don’t forget me,” Lo had said.

“You’ve gone away,” Charlotte remarks on the change in Humbert’s aspect after this bit of critical news. What’s he to do? For Charlotte–who he finally accuses of bossing him about (which he is delighted to do, to be bossed, he says, but every game has its rules)–isn’t one not to have her way. Finding the gun is loaded, when Charlotte had insisted it wasn’t, he contemplates killing her in order to salvage Lo for himself, but realizes he can’t pull the trigger. Feeling even some affection for Charlotte, he goes now to see her in her bath, but she’s not there though the water runs steaming hot. Charlotte has been in Humbert’s drawer reading his diary. Calamity! Humbert can have everything, Charlotte says, but she is leaving, and he will never see Lolita again!

Humbert rushes to fix Charlotte a martini. He calls to her from the kitchen that it’s not a diary at all, just notes for a novel. The use of her name and Lolita’s, that was simple coincidence, they were handy. In the meanwhile, Charlotte is out front being struck by a car.

Goodbye Charlotte.

You mean you never played that game when you were a kid?

Humbert rushes to retrieve Lolita, plans made for traveling with her, sleeping in hotels away from prying Ramsdale eyes. He says her mother is in the hospital near Lepingville. They won’t make it there that night however, only as far as the Hunted Enchanters hotel at Briceland. As it turns out, Hunted Enchanters is catching the overflow of a police convention so there are no rooms available except for, wait, Mr. Love hasn’t called. They can have Room 242 which has one double bed. An effort will be made to find a folding cot, but the double beds are large enough to sleep, well, once they had three women sleep in such.

Too coincidentally, who else is standing at the registration desk, near at hand, but Clare Quilty and his knowing companion, Vivian Darkbloom (an anagram for Vladimir Nabakov). They have been getting pictures. And they know what is up with old Humbert, and seem conspiratorially delighted. When opportunity presents itself, Clare, his face hidden, voice disguised, takes advantage of tormenting Humbert with innuendo. His talk jumps, nips, jabs, disintegrates and reformulates unexpected combinations like the constant background chatter of the constant companion of one’s mind. After Humbert and Lo have situated themselves in their room, and Lo has made itself clear she is aware of what her darling stepfather is up to, and that her mother would have their hides, when she suggests Humbert go down to check on the cot, Clare is on the scene to discomfit and perturb. On the darkened porch, when Quilty broaches conversation, Humbert says, “Oh, you’re addressing me? I thought there was perhaps someone with you.” To which Quilty replies, “No, I’m not really with someone. I’m with you. I didn’t mean that as an insult. What I really meant was that I’m with the State Police here, when I’m with them, I’m with someone, but right now, I’m on my own. I mean, I’m not with a lot of people, just you.” He suggests that he arrange for a bridal suite for Humbert and his little tall daughter.

The bizarre genius of Lolita is it is black comedy mixed with maudlin melodrama which becomes black comedy in the hands of all concerned. James Mason is phenomenal throughout. I have rewound video again and again in order to watch the Olympic scale of gymnastic expressions through which he pours the nervous, deceiving, vain, egotistical, and thoroughly criminal, pathetic Humbert. Beside the droll Sue Lyon he is a Titan of self-abuse hemorrhaging decrepit cruelties all over her naive precociousness. He and Shelley Winters beat Lucy and Dezi into the ground with baseball bats, then hop up and down upon their comedic graves. Peter Sellers is, of course, great, but he’s the crackly icing to the cake Mason and Winters had to whip up out of nails and salt.

It’s a delicate balancing act juggling so thoroughly underplayed, over-the top, comic wretchedness. A scene in which the hotel’s bellhop shows up with the cot which Humbert doesn’t want is a comic classic. Humbert repeatedly attempts to get the bellhop to go, just go, and at least to be quiet. But he doesn’t dare be too suspiciously persistent, so he helps the bellhop try to unfold the folding bed, which snaps shut its ruthless dragon jaws. He and the bellhop take their turns throwing themselves atop it, until finally the bed is supposedly tamed. After the bellhop leaves, Humbert prepares himself like a Cary Grant groom. Having likely scented his hair, dressed in probably his swankest robe over his best pressed pajamas, he emerges from the bathroom, ready for…well, ready but ever nervous about being caught. One can feel the breathing awareness of the hotel all about, as if it is itself an entity awake and watching, as in “The Shining.” So, when Lo wakes and notes the folding bed has arrived then stretches out so there’s no room for Humbert Humbert beside her, he sheepishly, disappointed, retires to the cot.

Which collapses. Last laugh for the night in what is a hideous situation out of which Kubrick and Nabakov, Mason and all else manage to keep milking some excruciating comedy.

In the morning, when Lolita suggestively flirts with him, he seems to have forgotten all about his plans for seduction, telling her to call for breakfast. But Lolita has other things in mind–just the kind of something which would gall dear mom. It’s not that Humbert is shy, he’s just got a lot to be careful about, and an awful lot to lose if he doesn’t pace things just so. It’s to his advantage to have Lolita seduce him, or believe she is seducing him. But before she does, first she shows how double-jointed she is, how her wrist folds back, and how her thumb folds back to her wrist.

It was hard by the dim lake of Auber,

In the misty mid region of Weir…

A case of Asiatic flu

Skip ahead to Beardsley College, past Humbert’s revealing to Lolita that her mother has died, so that Lolita understands she has nowhere to go but with him, he her sole protector now, the anchor for a child who can’t take care of herself. Skip past his supposed slavery to her whims, and her perverse imprisonment, silence the word as she dare not tell anyone the truth of their relationship, and all this while Lo is ever growing, ever threatening to keep growing up, which Humbert must stop if he can, must keep his nymph from becoming a hideous teen.

In both novel and movie, Lolita is sexually precocious, yes, but an understanding of the games she plays is out of reach of the child. Humbert’s fascination with Lolita in Nabakov’s novel is clearly the hunger of a depraved pedophile for a child whose nubile innocence is perversely, stubbornly twisted into provocation for desire. That is the pedophile’s rationalization, with a needless excuse further provided that Humbert’s childhood love died when she was about Lolita’s age, resulting in an emotionally and sexually-stunted individual who ever pursues that lost, first love. In Lolita the movie, for the audience it is less clearly all Humbert’s initiative. In the book as well as the movie Lolita is no longer a virgin by the time she leaves Camp Climax, and in the book she practices torrid kisses on Humbert, but in the book she is twelve years of age when they meet, and it is made clear that only two more years of desirability exist, that by the time she stretches into being a teen at fourteen, the Lo Hum had loved will be forever gone. In the movie, we have Lolita being played by a young woman who is of an age that Hum would have found repulsive in the book. An adult, or near-adult, is a giant of expectations, capable of making judgments. But a child, no matter how precocious, is someone from whom Humbert can steal sex and otherwise concern himself with keeping them quiet with gifts and threats. The delight of Hum having a child is they are utterly dependent and unable to make demands of any consequence. They don’t have the life experience, they don’t know what real consequence means. Because they are children. A child is someone from whom Humbert can sneak sex on the sly. Even if they are sold as prostitutes, the pedophile knows that they have the heart of a child, which is what they want. A victim. A prisoner.

Hum, in the novel, desires girl children of a certain sort. He sees them here and there. Initially, Lolita is his fascination more through her availability than any sort of specialness. A pedophile is classically an individual who may make their victim feel unique, but in reality they are not. That idea of enslaved/beloved uniqueness is a method of management and coercion the pedophile exercises over a number of children in his criminal career. This is less clear in the movie, and also loses its edge to a certain extent in the book, for in the book by the time Lo reaches the age of fifteen at Beardsley, her association with Humbert having gone on far longer than in the movie, Humbert is still fascinated with her, still enthralled with the child he continues to observe in her. At Beardsley we have Humbert doing what he can to keep his Lo from growing up and exercising freedom, so that the message divides its concern between the perversity of the pedophile and the overbearing demands of a veritable god/guardian who will not concede to his creature of Eden their free will.

Lo is, after all, not just little Lolita, but Lilith, the other wife of Adam who has been demonized through the ages. And at Beardsley, she is now making demands, and complaining, ripe with hate for her guardian prisoner, and conniving in any manner that she can to achieve a small measure of freedom for herself, which means she must lie, she must cheat, she must steal her small bites of independence from god Humbert. The slavery of the pedophile is not to his victim, but to his desire to work what wonders he can, in whatever way he can, to keep them quiet. To say at all that Humbert has even loved her is a misunderstanding of his true nature. He does not love, his only desire is self-satisfaction. He is by no means willing to make any sacrifice for her happiness; he is by no means willing to let her go. Every action god Humbert makes harms her, even if it appears beneficient.

So skip ahead now to the play in which Lo involves herself, in which she plays the lead. What a coincidence that it’s called “The Hunted Enchanters.” And, as the piano-teacher says, she has wondered if the symbolism isn’t at times a bit heavyhanded. As the audience, we are only given a glimpse of that play. Lolita is a nymph in garish make-up. Before her kneels goatish Pan. “Tremble no more nymph, the bewitcher’s bewitched.” His horns have been removed. And Lo, with a similar nymph companion, leads him away, announcing, “Let us take him to the dark kingdom.” The play deals in archetypes; let us not look here for Lo, the child. But let us look for Lolita.

Quilty himself has directed the play and afterward observes Humbert dragging Lo off, away from the prospect of attending the cast party, and asks his helper, Brewster, to go get him some Type A Kodachrome film. The implication is that he is recording all of Humbert’s criminal activities with the child, keeping a record.

The conclusion of Lo’s physical subservience to Hum is not far off. They fight. She battles, making it apparent how much she hates him. He decides he must get her out of there, must flee again. At first she resists, but after slipping away she calls and tells him that she is in agreement, that to flee that place is the thing to do.

On the road, they leave the East, they drive West. Population becomes thinner and thinner. They are out on the edge, moving further and further away from society in Hum’s desire to lock Lolita away in his veritable jail. Remove her from all communication with others. Lo to himself, entirely to himself. His aim is to make it to Mexico. Charlotte’s garden is now far behind. Desert surrounds.

Humbert suspects they are being followed and have been followed for three days. A tire blows. The car limps to the side of the road. A car which has been following stops behind them. Hum begins to experience what may be a heart attack but is in such denial of it, so eager is he to keep on going, to give in to nothing, that he virtually ignores it away. But now Lo states she is sick. She feels awful. Must be the Asiatic flu. She ends up in the hospital. Humbert is also ill with the flu. He recieves a disturbing phone call that questions his conduct with Lolita and how he’s satisfying his sexual desires as a single male. The call is presented as a real one, but Humbert’s illness is such that hallucination isn’t out of the question, especially considering Quilty’s role as his tormentor, and that he is “only with” Humbert, as Quilty has said, as if he is Humbert. Humbert rushes to the hospital to get Lolita and flee with her yet again, but she is gone. She has been signed out by a supposed uncle. Humbert complains he doesn’t have a brother, but when the option is given to call the police, he suddenly remembers Gus. Yes, of course, he has a brother named Gus. He had forgotten all about Gus coming to get Lolita.

The tormenting delirium of that phone call echoes, though is more forward than, the stuttering man who had challenged Humbert at the Inn. Again, at Beardsley, Quilty had appeared to Humbert in the dark of his home as Dr. Zempf, a psychologist with coke-bottle thick eyeglasses, supposedly let in by Lolita to wait for him, hinting at how Humbert didn’t want anyone nosing about his home affairs, and if he didn’t then the thing to do was to permit Lo to be in the play. The character of Dr. Zempf, resembles that of Dr. Strangelove and does more than hint, his talk has a conspiratorial air to it. If Humbert will play the game as he proposes, allowing Lolita in the school play, then suspicion may be waylaid; Lolita and Humbert may continue on as a seemingly normal father and daughter. Yet, it is after the school play, Lolita and Humbert screaming at each other back at the house, that a neighbor comes by and says she can hear everything, as well as the minister who is visiting next door, and declares that everyone is beginning to wonder about their relationship anyway.

As Charlotte had said of her garden, it was the talk of the neighborhood.

Finally, it is the hospital and the Asiatic Flu that separates Lolita from Humbert. One will recall that when Humbert sat on her bed, after she had been torn away from him to attend Camp Climax, above his head there had hung the poster emblazoned “Tokyo.” When next Lo and Humbert meet, she will tell him all about Quilty, amazed that he hadn’t guessed who her other lover was, the only man she ever cared about, who had attracted her with his Oriental, Eastern sensibility. An absolute genius, a breed apart from Lo, from Humbert.

The Mother

Several years pass and Humbert receives a letter from Lolita. She is asking for money. She and her husband are expecting a child. They want to start a new life elsewhere.

It is a scene straight out of Peter Pan. Humbert, in fancy coat, appears at Lolita’s home, and though appalled by this pregnant woman in eyeglasses, begs her to leave with him, to return to their former life.

Humbert pleas that he wants Lo to live with him, die with him, “and everything” with him. He wants to start fresh and forget about all that has happened. “There’s nothing here to keep you. You’re not bound to him in any way, as you are bound to me by everything that we have lived through together, you and I.”

Lolita responds that she’s going to have Dick’s baby in three months, that she’s wrecked too many things in her life and can’t do that to her lamb, her good man, Dick, who needs her, who sees her as good, as a good kid who will make a good mother. When Lolita had learned of her mother’s death, Humbert had asked her to stop crying; Lo now asks Humbert to stop crying.

If I find any fault with Sue Lyon, it is in this scene. She behaves like a child playacting at being an adult. Perhap this is what Kubrick wanted but it comes across as bad acting on Lyon’s part. And it may be what Kubrick wanted. In my opinion he had a fiendish habit of sometimes implanting what seem obvious weak elements, as if to keep a film from being too perfect, a flaw against which the viewer must squint their eyes in deference to the brilliance of the remainder of the work.

It is impossible, of course, for Humbert to retrieve Lolita, and he knew it. For which reason he has already a couple of checks made out to her, one from rent on her mother’s house, which is rightfully hers, and another from the downpayment on its sale. In total, she will eventually receive $13,000. To Lolita this seems quite a bit of money, but we all know that it was a high price to pay, and far too little for what she has experienced. That no payment can erase the past which she insists is behind them.

The movie then returns to the beginning, Quilty being sought by Humbert, pursued through hazy fog to his lair.

Or almost its beginning.

The real first scene of the movie is that over which the opening credits run, showing a dainty feminine foot, its nails painted by the subservient hand which cradles it. One is reminded of the phrase found in the Book of Proverbs, 5:5. “Her feet go down to death, her steps take hold on the netherworld.” This is Lilith, the stange woman, the seductive dancer often associated with the Queen of Sheba.

Lolita/Lilith is painted here, by Kubrick and Nabakov, as a child without blame, innocence defiled by misuse, abused, imprisoned and wrongly seen as the instigator of evil by one who is older and should know better–in essense, by a blind sort of god who, as Clare Quilty puts it, “Likes to watch.” Kubrick had made a fledgling stab at a Lolita-type character in Killer’s Kiss, which he wrote. It assists perhaps in an understanding of what appealed to him about the Nabakov story. Killer’s Kiss had as its female protagonist a woman whose background was suggestive of some sort of abuse, whose mother died when she was born, whose father seemed virtually non-present for her, while in a peculiarly close relationship with her sister. At about the age of fourteen or fifteen she became a dance hostess in a seedy club named Pleasureland (Eden) out front of which we’re several times treated to a sign that reads the “Queen of Sheba.” The story involves her attempting to extricate herself from that world, from her boss’ obsession. He too holds her captive. She also is blond (in the novel, Lolita is brunette) and carries around a pathetic little blond doll suggestive not only of her childhood but the child that she partly is, despite her physical maturity.

There are essential differences between the book and movie which are interesting. The mother in the movie bears scarce resemblance to the mother in the novel. In the novel, when Humbert flirts with the idea of killing Mrs. Haze, it is when they are swimming. He plots to drown her then decides not to, and a good thing to as it turns out there would have been a witness. The novel also has as one of its backdrops youthful America’s penchant for novelty and crass commercialism, likening America with a child in its fascination for the bright, the gaudy, the kind of peculiar inversions that can make a trashy side-attraction of spectacular, natural scenery while a sugary, bubble-whispery Coke is the enduring treasure which makes the experience. This is only fleetingly communicated in the film, because this is one of Kubrick’s movies where he is particularly involved with faces rather than places. The characters are never overpowered by the setting; not even in Quilty’s mansion, where one has the impression of it being the brain of a shattered, tormented god maddened by the splintering of the initial Big Bang.

Fade out on the shot of the Thomas Gainsborough-style painting of the woman in her hat riddled with bullets.

* * * * * *

Lolita

Directed by Stanley Kubrick

James Mason–Humbert Humbert

Shelley Winters–Charlotte Haze

Sue Lyon–Lolita Haze

Marianne Stone–Vivian Darkbloom

Peter Sellers–Clare Quilty

Released June 13, 1962 (USA)

(Originally placed online 20000. Migrating over from another section of the website.)

Leave a Reply