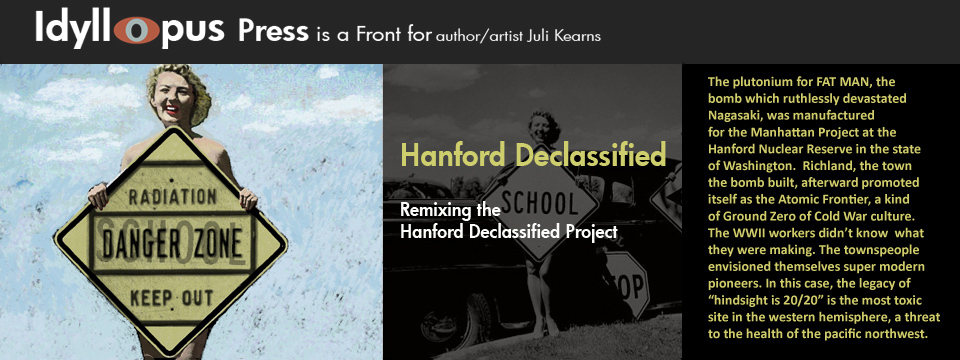

Where the old west greets the new, declassified

2005

25 w by 19 in h inches

Digital Painting

Based on a photo from the "Hanford Historical Photo Declassification Project".

© copyright Jk

Read the introduction to the Remixing the Hanford Declassified Project paintings

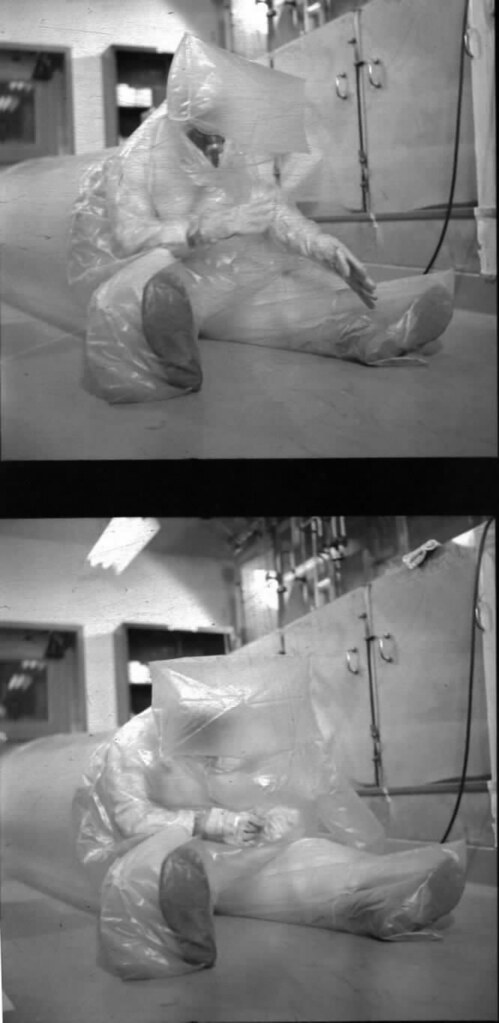

And the welcoming committee was Plastic Man

"C'mon, kids! Wave at Reactor Man!"

Actually, he was known as Plastic Man.

DDRS Record Details for Record Accession Number

"N1D0003098"

Accession Number N1D0003098

Document Number 9010-NEG-G

Alternate Document Number 9010-NEG

Title Description ATOMIC FRONTIER DAYS PARADE

Document Date 07-Aug-1954

Public Availability Date 14-Feb-2002

Yes, we have here a proud General Electric entrant in a Richland Atomic Frontier Days Parade. Which may be a shocker to non-Richlandites, that Richland had Atomic Frontier Day celebrations in the summer, that there would be a float congratulating the start up of the first reactor and that Plastic Man meets Rawhide was great entertainment.

Not that it isn't.

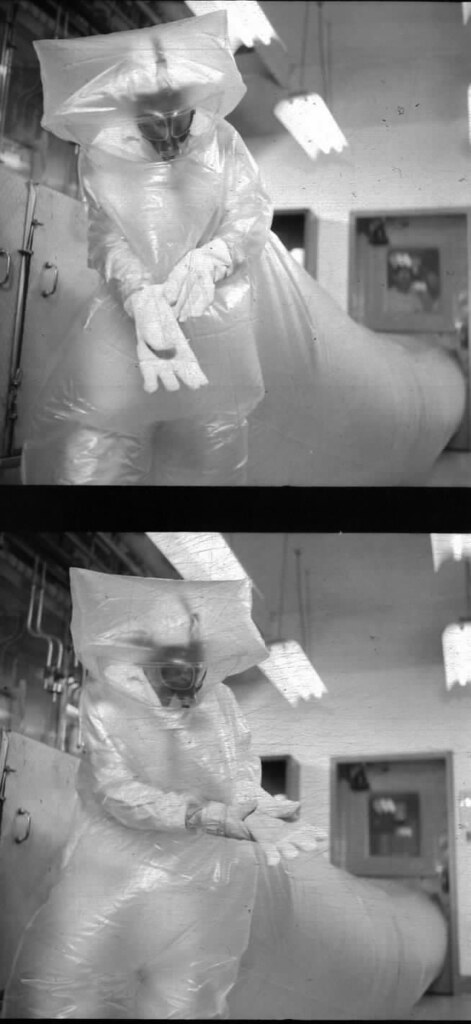

You have to admit that Plastic Man could be pretty endearing. He looked like a cross between a wind-up doll, a mime, a robot, and Wonder Bread wrapping.

DDRS Record Details for Record Accession Number

"N1D0013480"

Accession Number N1D0013480

Document Number 6634-1-NEG-D

Alternate Document Number 6634-1-NEG

Title Description PLASTIC MAN - 231 BUILDING, 200-W

Document Date 17-May-1954

Public Availability Date 14-Feb-2002

DDRS Record Details for Record Accession Number

"N1D0013484"

Accession Number N1D0013484

Document Number 6634-1-NEG-H

Alternate Document Number 6634-1-NEG

Title Description PLASTIC MAN - 231 BUILDING, 200-W

Document Date 17-May-1954

Public Availability Date 14-Feb-2002

He was apparently a scintillating interview.

DDRS Record Details for Record Accession Number

"N1D0002668"

Accession Number N1D0002668

Document Number 8957-NEG-D

Alternate Document Number 8957-NEG

Title Description PHOTOGRAPHING PLASTIC MAN

Document Date 04-Dec-2001

Public Availability Date 14-Feb-2002

DDRS Record Details for Record Accession Number

"N1D0013497"

Accession Number N1D0013497

Document Number 6634-1-NEG-U

Alternate Document Number 6634-1-NEG

Title Description PLASTIC MAN - 231 BUILDING, 200-W

Document Date 17-May-1954

Public Availability Date 14-Feb-2002

DDRS Record Details for Record Accession Number

"N1D0013473"

Accession Number N1D0013473

Document Number 6633-1-NEG

Alternate Document Number 6633-1-NEG

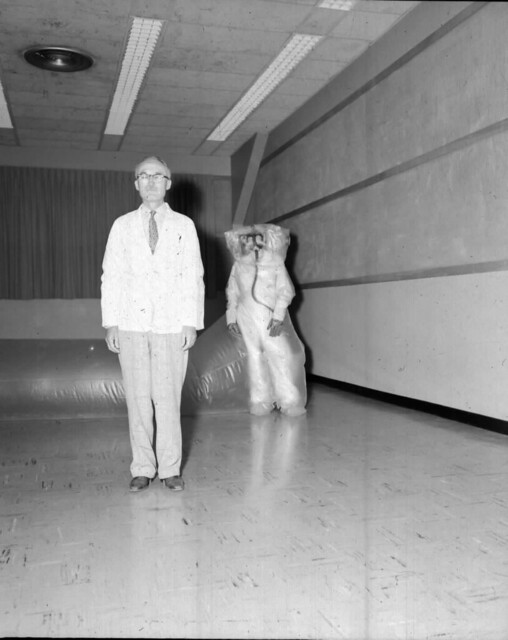

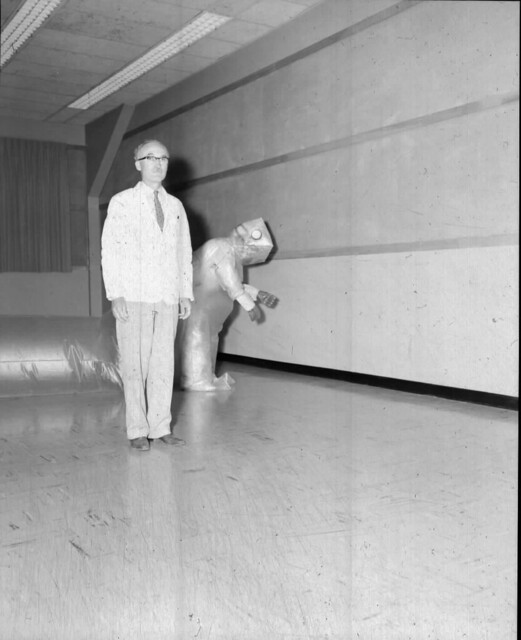

Title Description DOCTOR NORWOOD AND PLASTIC MAN

Document Date 02-Aug-1954

Public Availability Date 14-Feb-2002

DDRS Record Details for Record Accession Number

"N1D0013475"

Accession Number N1D0013475

Document Number 6633-1-NEG-C

Alternate Document Number 6633-1-NEG

Title Description DOCTOR NORWOOD AND PLASTIC MAN

Document Date 02-Aug-1954

Public Availability Date 14-Feb-2002

There are people who probably wish they'd been living in Plastic Man's bubble, particularly those who were downwind of Hanford. Betweeen 1944 and 1951, 727,900 curies of radioactive iodine were released from Hanford.

"Got milk?"

If you lived downwind you had non-quality milk spiked with a bit of radiation.

Health officials for the Manhattan Project knew as early as the spring of 1943 that the ingestion of stable, nonradioactive iodine could protect both workers and the public from Iodine-131 exposure. One of these early health officials was Dr. W.D. Norwood, who later served as Hanford's medical director.

Nevertheless, it was not until 1948 that crude filters were installed on the plant stacks, which did little to stop the radioactive materials and hazardous chemicals spewing into the air and into the Columbia River. Some of these releases were in the form of "hot radioactive particles" that contained plutonium, ruthenium, strontium and cesium. Hanford tracked these particles as far as Idaho, and even into Montana.

Catastrophemap

Yes, that Dr. Norwood. The one in the last two photos with Plastic Man. He knew.

Nagasaki, milk contaminated by radioactive iodine, and Hanford as the western hemisphere's most toxic waste site, I view as more than just a little subcontext to the images of Hanfordites and Richlandites declassified in the late 1990s as part of the Hanford Declassified Project--people partying, parading, painting, gardening--celebrants of life as the new brave frontiersmen and frontierswomen straddling that boundary between the pre-nuclear wild west and the the post-Nagasaki world in which Plastic Man was your Good Neighbor.

The Jetsons were just around the corner, up in the sky. We all thought they wanted to live there because there seemed to be no traffic in space. Instead, they were escaping what was earth-world, which they didn't want to discuss.

1944-1951: 727,900 curies of radioactive iodine released

1999 Tri Cities Herald article By John Stang, Herald staff writer

It was the great roundup of 1946.

Soldiers and health technicians hopped in jeeps and secretly roped sheep and cattle grazing near Hanford.

Then, they pressed Geiger counters to the animals' thyroids to check for the presence of radioactive iodine 131.

The roundup was ordered by the late Herbert Parker - a formal and aloof English radiologist who was Hanford's first chief of health and safety.

Parker fretted about the huge clouds of iodine 131 gas spewing from the stacks of central Hanford's B Plant and T Plant - where plutonium was chemically extracted from nuclear fuel rods.

Parker knew iodine 131 affected thyroid glands. But he didn't know what amounts were unsafe for people. It was a problem he kept trying to calculate.

He and other scientists had struggled for years to find out how iodine 131 - which loses half its radioactivity every eight days - enters human bodies.

Early on, they believed iodine and other radionuclides settled on vegetation that birds and animals ate. And they noted hunters ate game animals.

In the late 1940s, technicians stalked rabbits, coyotes and birds to find excessive amounts of iodine 131 in their thyroids, according to On The Home Front, a Hanford history book written by longtime site historian Michele Gerber.

For decades, the government kept secret any speculation about the risks of radioactive iodine to folks downwind from the plutonium plants. The official word was Hanford's neighbors had nothing to worry about.

But in the government-owned town of Richland, home to most of Hanford's workers, there were some curious rules that seem aimed at preventing iodine 131 from moving through the food chain, Gerber noted.

Chickens and livestock were banned, and Richland pasture land was off limits for grazing. The government constantly was testing the milk and water.

Richland's milk supply came from the Yakima and Ellensburg areas - upwind of Hanford. Hanford officials often cautioned Richlanders against drinking "poor quality" milk from the rural areas near town, Gerber said.

Milk from cows grazing on contaminated pastures is one of the most direct ways for radioactive iodine to reach humans.

Although Gerber didn't find evidence directly linking the Richland rules to iodine hazards, the circumstantial evidence is there. "You certainly have to raise the questions," Gerber said.

Of course, for most of the past 50 years, no one outside a small cadre of experts was asking serious questions about Hanford emissions, despite the threat to human health.

Releases of iodine 131 from Hanford smokestacks began soon after the first nuclear reactors fired up at Hanford. By far, the greatest releases of iodine 131 came from 1944 and 1951, when emissions totaled an estimated 727,900 curies. After 1951, special filters and other safety practices cut emissions dramatically.

In fact, 98 percent of the overall curies of iodine released over the 28 years ending in 1972 went out the stacks in the first eight years of Hanford operations, according to the Hanford Environmental Dose Reconstruction Project.

The iodine emissions accounted for nearly all the radiation doses from all types of airborne releases at Hanford.

A key reason for the peak during those early years of the Cold War was that Hanford was experimenting with ways to increase plutonium production.

One way to get plutonium quicker was to shorten the time that irradiated fuel rods cooled before going to the extraction plants. A side effect of shorter cooling times was that the radioactive iodine didn't have as long to decay before the fuel went into the plants.

As a result, thousands of curies of radioactive iodine routinely were sent out Hanford's smokestacks. By contrast, about 15 curies of radioactive iodine was released in the 1979 Three Mile Island reactor incident in Pennsylvania.

The wall of secrecy surrounding Hanford began to crumble as the Cold War drew to a close in the late 1980s. Among the thousands of pages of declassified documents was an account of the so-called Green Run of 1949.

In terms of radiation dose, the Green Run's 8,000-curie release pales in comparison with the years of routine emissions. But the federal government's decision to use the Northwest as an outdoor laboratory for radiation experiments still rankles many.

Much about the Green Run still is classified, but numerous clues indicate America's Cold War scientists wanted to learn how to monitor Soviet nuclear weapon production by tracking iodine releases.

So an intentional release of iodine was set up at T Plant. It was dubbed the Green Run because so-called "green" fuel was used. That fuel had cooled only 16 days instead of the then-normal 90 or more days - giving iodine little time to decay.

Scientists wanted a night experiment when cold layers of air near the ground would keep particles airborne until they were diluted. Plus, they wanted no rain, no low clouds and light winds. They figured 4,000 curies of iodine would be released.

But the night of Dec. 2-3, 1949, was cloudier than expected, and the winds kept shifting. Calculations were off, and almost 8,000 curies of iodine 131 were released.

And soon afterward, rain and snow came to force the iodine particles down all over the inland Northwest. One follow-up iodine 131 reading on vegetation in Kennewick was almost 1,000 times the limit set at that time.

In 1950, special filters were put on the processing plants' smokestacks to capture iodine. Emissions dropped to a fraction of previous counts.

But Hanford had an accidental release of 15,000 curies over several weeks in 1951 when the filters failed.

Meanwhile, scientists kept researching iodine 131's health effects.

They fed iodine 131 pellets to sheep kept at a facility near Hanford's F Reactor in 1950 and 1951 and did autopsies on the carcasses. The then-classified study showed thyroid damage and changes in blood and hormone levels in the sheep.

Also in 1951, the Atomic Energy Commission - the forerunner of today's Department of Energy - released a public report that declared releases of iodine 131 and other radionuclides were low and posed no hazards to plants and animals.

Gerber noted all Hanford's iodine and thyroid studies were kept classified until the 1980s.

Scientists continued studying iodine and thyroid disease at Hanford and elsewhere.

In 1954, Hanford scientists were sent to Utah to check on sheep killed from iodine-laced fallout from atomic bomb tests, she said.

Meanwhile, some research addressed strong suspicions that iodine 131 landing on vegetation came to humans through cows' milk.

"They didn't get the connection with milk for a long time. They knew (iodine) landed on the vegetation," Gerber said.

In 1963, an AEC scientist publicly acknowledged that link with a report on the abrupt increase of iodine 131 in milk and subsequently in human thyroids after atomic bomb tests in Nevada, Gerber said. She believes the AEC was certain about the connection prior to that publication.

However, it was not until the mid-1980s that public questions and concerns about Hanford radiation releases and people's health gained major momentum.

That was spearheaded by newspaper articles on "downwinders" and a massive 1986 release of 19,000 pages of previously classified documents that included information on iodine and thyroids.

The federal Centers for Disease Control began pondering the need to find out how much radiation people living "downwind" of Hanford would have absorbed from 1944 to 1972. And the agency thought a study was needed to see if a link existed between Hanford's iodine emissions and the region's thyroid problems.

DOE agreed to a dose-reconstruction study, and it put Hanford contractor Battelle in charge.

But public concerns surfaced whether DOE and one of its contractors could conduct an impartial and credible study on Hanford emissions. So an independent panel of scientists -dubbed the Technical Steering Panel - was put in charge.

Much of the public didn't believe the panel had the clout to assert its independence. And Battelle - while sharing technical data - balked at sharing budget information on the research.

The panel had to pressure Battelle to open up. And it requested overall responsibility for the study be shifted from DOE to improve credibility.

In 1992, the Department of Health and Human Services assumed responsibility for the study, and CDC began providing the money.

In 1994, the panel unveiled its final estimates on how much airborne radionuclides - dominated by iodine 131 - Northwest downwinders likely absorbed through the food chain.

The numbers varied according to geography, ages and eating and drinking habits. Babies and children were among the higher risks. And these were just estimates within ranges of maximum and minimum possible doses.

Many average doses were a few hundred times the levels people would receive from naturally occurring background radiation. The remainder varied widely, from a few dozen times that of background levels to a few thousand times background levels.

The big problem was: What did these numbers really mean when looking at thyroid problems?

And that's what the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center's thyroid study - begun in 1991 - was supposed to tell Thursday.

Copyright 1999 Tri-City Herald. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.

Read also "Life" Magazine's 1954 article on Plastic Man.

"The Department of Energy, Richland Operations Office (RL) has aggressively implemented the commitments made by the Federal Government to openness in Government which was stated as a 'Fundamental principle that an informed citizenry is essential to the democratic process and that the more the American people know about their Government, the better they will be governed. Openness in government is essential to accountability . . .' RL is committed to responsible openness. The Hanford Declassification Project (HDP) was initiated by RL to declassify to the maximum possible extent all previously classified Hanford operations information (documents and photographs). There are over 77,000 declassified photographs of early Hanford (1943 - 1960) available... \These World War II and Cold War era photographs depict early Hanford construction and the employees/families who lived and build/operated the site."

The plutonium for the bomb dropped on Nagasaki was manufactured at Hanford.

Originally published on my blog in December 9 of 2005.