Comparing Hitchcock's Treatment of a Significant Window in Spellbound with Kubrick's in The Shining

"Something is happening."

Go to Table of Contents of the analysis (which has also a statement on purpose and manner of analysis and a disclaimer as to caveat emptor and my knowing anything authoritatively, which I do not, but I do try to not know earnestly, with some discretion, and considerable thought).

Hitchcock's 1945 Spellbound opens on a mental hospital and a patient being called away from a card game she says she was sure to win, that she'd had a perfect hand. On the way to her appointment, she flirts with the attendant who accompanies her. When he is drawn in and reciprocates, she scratches his hand.

The injury is enough that he covers his hand with a handkerchief as he leads her into the office of psychotherapist, Constance Peterson, played by Ingrid Bergman. The woman confesses to Constance that she does indeed hate men, and relates to her a story about how she became so angry with one who proposed marriage to her that when he believed they were going to kiss she bit his mustache right off. She then becomes furious with Peterson, she feeling that Constance believes herself superior to her. She calls Constance "smug" right before she is led away for raising a ruckus in Constance's office. So, the first woman encountered is one who is depicted as having a feline, two-faced, lying, manipulative, vicious nature. Constance will turn out to be a wholesome type who enjoys sex and becomes hungry for liverwurst when crushing on someone.

The hospital at which Constance works has been awaiting their new head, Dr. Edwardes. When he arrives, he's handsome Gregory Peck, which is unexpected. He was supposed to be an old guy, like the outgoing head, Dr. Murchison, and Ingrid promptly falls for him, in both the film and in real life, taking off her alienating glasses and revealing her beautiful, absolutely receptive eyes. But when she sketches the outline of a planned pool, with a fork, that leaves multiple tine lines on the tablecloth, Edwardes becomes agitated and vehemently chastises her.

A theme in the film are these multiple track lines, as they have everything to do with how Dr. Edwardes is not really Dr. Edwardes but instead John Ballantyne. He is a man with amnesia who believed he was Dr. Edwardes but once he reaches the institution he realizes he is not. And Dr. Edwardes is nowhere to be found. The amnesiac divulges all this to Constance and wonders if he murdered him. Constance intuits he is a good man and is pretty confident he did not, that instead he believes he murdered him because he feels guilty for an unresolved issue in his childhood. As the amnesiac is, over and over, driven to distraction and collapse by the site of parallel lines, certainly this pattern must have to do with the mystery of who he is and what has caused his trauma. By the time others realize he isn't Edwardes and police arrive on the scene, he has fled to New York, leaving a note for Constance. She follows him to his hotel where we have a scene that doesn't have either the scratching or parallel lines but recalls the female patient harming the attendant's hand when Constance realizes the amnesiac has recently had such a severe burn on his hand that he's had a skin graft. She grasps his arm as he spreads his fingers, the camera focusing on his hand as it had on the hand that had been scratched. How did he get the burn? he doesn't recollect.

The scar begins to pain him and he covers his hand just as the attendant had done.

What is peculiar about the theme of the parallel marks is that these are supposedly Peck's preoccupation, they have to do with him, his forgotten experience, the reason for his trauma, but they have also to do with the audience as Hitchcock introduced these parallel lines, via the duplicitous woman, before Peck entered the film. The audience may even forget, by the time Peck's preoccupation is revealed, that the hand scratching incident had even occurred, or they might not connect it as being a part of this theme.

Constance's idea that the amnesiac hasn't murdered Edwardes but is instead suffering trauma from a childhood episode that has been revived somehow in connection with Edwardes' disappearance, was also prefigured by another patient who was in her office when the amnesiac, as Edwardes, arrived at the institution. This patient was a man who believed he'd murdered his father, though he hadn't. He was among the first to see Edwardes' arrival through the window and so a direct connection between the two is forged by Hitchcock. At that point, we don't know yet that Peck is an amnesiac, that he isn't Edwardes, or that he is suffering an uncovered trauma from childhood. The male patient also suffers from this same misappropriated guilt, and this guilt is transferred, by Hitchcock, from him to Peck when the patient sees Peck's arrival.

The amnesiac's obsession with parallel lines is caught by the train tracks as he and Constance travel to the home of doctor who had mentored her, where she hopes they'll find refuge. When the amnesiac has just recollected he was injured during the war when his plane was shot down, he becomes upset with Constance pressuring him with questions and observations and says that if there's anything he hates it's a "smug" woman. For some reason Hitchcock has chosen to return us to the initial, manipulative female patient who had also called Constance "smug" when her deportment is instead, with the amnesiac, enthusiastic concern.

At the home of Dr. Brulov, for whom Constance had been an assistant, we have the famous analysis of the dream sequence that was designed by Salvador Dali. How I came to watch Spellbound again, in the first place, was through viewing the 1953 animation of Edgar Allen Poe's "The Tell Tale Heart", directed by Ted Parmelee, designed by Paul Julian and animated by Pat Matthews. Edward Hopper's "House by the Railroad" is frequently given as an influence for the Second Empire house in Hitchcock's Psycho. I have yet to find a Hitchcock interview that confirms this, and I'm not saying that Hitchcock might not have also referred to Hopper's painting in the design of the Psycho house, but I instead believe that the initial inspiration is perhaps found in the opening of The Tell Tale Heart animation where we observe a Second Empire mansion in a scene of dark, barren desolation. What's more, the mansard roof of this home in The Tell Tale Heart has iron cresting on its mansard roof, as does the Psycho house, and the Hopper house does not.

But I wouldn't go so far as to propose this inspiration if not for the fact that The Tell Tale Heart seems to itself refer to Dali's dream sequence in Spellbound, a film certainly influenced by surrealism, concerned with a person who murders an old man as he is haunted by a milky eye of his. On the left below is a grab from Spellbound, in which severe shadows move over a table, at the head of which is an old man, during a card game during the dream sequence. I would propose we see a reference to this in The Tell Tale Heart. On the right, at top, a severe and elongated shadow moves across the floor toward an old man seated at a table playing cards. Next we are shown this is an old man playing cards.

It seems sensible there may have been a dialogue between these films. The Tell Tale Heart draws inspiration from Dali's work in Hitchcock's Spellbound, and Hitchcock later responds to The Tell Tale Heart with the mansard-roofed house in Psycho. By the way, there is no card game mentioned in The Tell Tale Heart.

Kubrick at least a couple of times seems to refer to Hitchcock films in his cinema, both Psycho and Vertigo recalled in Lolita. As James Mason narrated The Tell Tale Heart, a story by Edgar Allen Poe, and James Mason plays Humbert in Kubrick's Lolita, in which Humbert not only quotes from Poe, but Kubrick appears to take a cue from the horror of the shower in Psycho when Humbert approaches the bathroom with every intent of killing her, it seemed to me reasonable that Kubrick might have been influenced also by Spellbound and would have likely referenced it at some point, but I couldn't recollect any such scene.

A couple of nights after watching The Tell Tale Heart is when I decided to watch Spellbound again, which I had planned to do a while before but had never gotten around to it.

As I could recollect no references to Spellbound in Kubrick's work, I didn't approach my watching thinking of anything but enjoying Spellbound.

Labyrinths are common in films, and occur in almost all of Kubrick's films. As labyrinths are common I had no "ping" when I saw that what reveals Peck as not being Edwardes is a book by Edwardes, titled Labyrinth of the Guilt Complex, that's in the library of the mental health institution. It has been signed by him. Constance accidentally discovers Peck is not Edwardes when she sees the signature in the book as compared to Peck's handwriting. They aren't the same.

For Hitchcock, in Spellbound, the deja vu maze that Peck wanders about in is one constructed by unresolved guilt.

Toward the end of the dream sequence in Spellbound, Peck relates that he is chased, down an incline, by what seems like a giant bird. The movie makes some absurd leaps, reasoning from the card game that he must have been at the 21 Club in New York. (We may realize that this dream card game, in which an older man states he has "21" and wins, only to show blank cards and be accused of cheating, was foretold by disrupted card game that opens the film, the manipulative patient having stated she had a perfect hand.) Though there is no skiing in the dream, Constance and the elder psychoanalyst somehow deduce from the incline down which Peck runs that he was skiing at some resort, and that the winged figure in pursuit of him is Constance's angel. It's proposed perhaps he was at Angel Valley. Peck now recollects he was instead at Gabriel Valley and that he had been skiing with Edwardes when he had a skiing accident there, going over a slope.

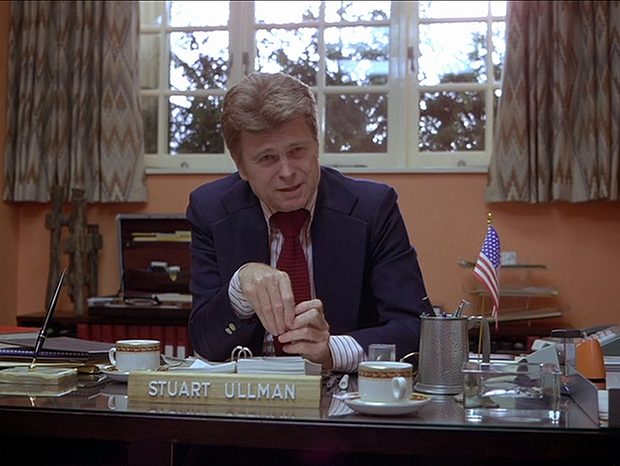

Gabriel is, by some accounts, the angel that announces the Day of Judgment by blowing a horn, the shofar, sometimes called Gabriel's horn. The Shining opens with the feel of something like an omniscient bird following Jack as he makes his way to the Overlook up the Going-to-the-Sun Road. I have written extensively, in my analysis of The Shining, on Dies Irae playing over the opening shots, Kubrick having chosen music that concerns the Day of Judgment. Birds appear frequently in the film, not physically, but in illustrations and even in a bird carving that is situated in the window behind Ullman's desk. There was the bird on Jack's t-shirt, a mascot of the school where he formerly taught, and a bird that looked much like those in Hitchcock's The Birds was on shirts worn by the film crew during The Shining.

Before continuing, I should state that in Kubrick's films there can be multiple influences for any one symbol and how Kubrick uses it.

That Kubrick might have found partial inspiration, in Spellbound, for the seeming intelligence that accompanies Jack on his drive up to the Overlook, that's expressed in a bird-like manner, I might not have considered, however, if not for the revelation directly preceding the amnesiac's recovering his memory of Gabriel Valley.

And that's the window.

The amnesiac has finished relating his dream. He sits up and is given a cup of coffee. We see beyond him a window and indistinct shapes moving in the white of the window. Peck turns away from it, intensely bothered, saying that something is happening.

Brulov proposes that what he's experiencing is photophobia, fear of light. Constance says it's instead the snow.

She realizes it's the bright white snow and tracks being made in the snow by the people sledding that are bothering Peck. These must be connected with his amnesia.

Based on the revelation of the window, as the amnesiac sits staring toward the camera in a state of spellbound shock, Constance and Brulov reason out the winged figure that had pursued him down the incline. Was it a harpy? No, an angel. He must have been at Angel Valley. The amnesiac remembers he was at Gabriel valley. After this, the amnesiac and Constance go to Gabriel valley to make a skiing run, hoping to completely unlock the memory the amnesiac has been reluctant to encounter. He recollects that when he was a child he was sliding down the concrete incline of a bannister next some exterior stairs, playing with his brother who was seated at the bottom the bannister, and that his brother had moved out of way of his feet only to accidentally fall upon and be impaled by an iron fence at the foot of and beside the stairs. It was ski tracks at Gabriel Valley, where Edwardes went off over the cliff, that had deja-vu connected with Peck's brothers death--the parallel lines on that concrete bannister down which he'd slid, the parallel lines of the fence, his brother falling upon the railing--which had revived that guilt, which he couldn't tolerate, and caused his amnesia. With this realization, the amnesiac is instantly cured and recovers his memory, his identity returned to him. As it turns out, he has not fully recovered the whole story, he has not remembered yet how Edwarde's was killed. A wheel that had appeared in his dream was a revolver held by Dr. Murchison who had shot Edwarde's, which had caused him to go over the slope. It is Constance who later reasons this out, saving John (the amnesiac) from life in prison. But that isn't relevant to The Shining. What I am concerned with is how Hitchcock's use of the window may have influenced Kubrick.

We never are able to see out Kubrick's windows in The Shining. Even before the snow storm descends, we have the glare of bright light (as if off snow) impeding one's view out every window. That bright glare persists even after the snow storm. We are shown how the windows outside are covered with snow, we shouldn't be able to see out them, and yet the white glare persists.

Kubrick, after Killer's Kiss, tends to not show exteriors through windows in his films, with the exception of when one is driving in the car, or in 2001. His windows, viewed from inside, are either obscured by light or curtains. So the window in Ullman's office, out of which we can see nothing but a bit of foliage, and glare, is not unusual for Kubrick's work. It is also not unusual, as far as a Kubrick film, for being an architecturally "impossible" window, for Kubrick has impossible windows in Lolita, as well as in Eyes Wide Shut. However, it is in The Shining that Kubrick makes an impossible window almost a character, the glare of light through it, over the course of the interview scene with Ullman, becoming ominous, even sinister, that scene also overlooked by the eagle sculpture situated in the window.

Ullman wears a striped shirt that would have set off Peck's fear of parallel lines. No doubt the parallel lines on the flag on his desk would have done so as well. The Shining is a labyrinth of deja vu for Jack, and parallel markings don't play a part in this.

In Spellbound, the snow outside the window had on it the imprint of the parallel lines, shadows against white, that had set Peck off. "Something is happening." There is no physical snow at this point in The Shining, bur we view, on a wall opposing the window, two old sepia photographs that appear to show shadowy figures against snow, perhaps outside the hotel's maze. The indefinite feel of these figures is ghostly, like a vague memory, or a dream.

Later, when Wendy and Danny are out playing in the snow...

...Jack stands transfixed, spellbound, before the glaring light of a window in the Colorado lounge, his face fixed in what has become a well-known, stereotypical Kubrick glare. In this scene, we might be reminded of Peck's spellbound, shocked gaze when he's turned away from the window that gives entrance to the terror in his subconscious, a memory that is blanketed by amnesia.

Later, a window is emphasized again, one beyond the television on which Wendy and Danny watch The Summer of 42. The television has no cord. This could be for aesthetic reasons, but I think it also gives us an opportunity to look upon the movie as having more import than a random flick. Something that connects to the past. When Danny goes upstairs, he finds his father once again seated staring at the soft yet glaring light of the window.

Of course, I can't say definitively, absolutely that Kubrick shows any Spellbound influence in these window scenes in The Shining, but I think the subject bears consideration, especially due the psychological impact of the window as a view onto the subconscious in Spellbound. Whereas Peck's character, traumatized by the deja vu shadows his subconscious keeps throwing at him, initially resists memory, becoming amnesiac, he persists in confrontation until he ultimately remembers what has been chasing him. Jack's character instead, devoured by that labyrinth of guilt, blindly gives in and loses himself, resolute that none of what is transpiring at the Overlook has anything to do with him, convinced that Wendy and Danny are the root cause of all his problems.

But I'm less interested in the effect of the windows on any characters in The Shining than how Kubrick intended them to affect the audience. In A Clockwork Orange, the sets become associated with theatrical stages, and windows become the audience beyond the footlights. In The Shining, we've scenes again in which the windows relate directly to the audience and, as observed in the Ullman interview scene, are intended, it would seem, to have a subconscious influence on the viewer who likely hasn't realized that the window is entirely impossible, despite Kubrick having already shown us that a hall runs behind Ullman's office. The viewer tends to trust what they are shown in the moment. If a window is in the room, then a window belongs in the room. A bit of magic is had in how they accept the window, but perhaps there is a part of them that recognizes the window shouldn't be there and its presence vaguely discomfits them, not too unlike how Peck is bothered by the window and turns away from it saying that something is happening. He means that something is happening subconsciously but he doesn't know yet what that something is. All he knows he is bothered by the window's presence.

March 2019. Approx 3290 words or 7 single-spaced pages. A 25minute read at 130 wpm.

Return to the top of the page

Return to Table of Contents for "The Shining" analysis

Link to the main Kubrick page for all the analyses