Examining the Opening of The Shining in Relationship to the Nietzsche Stone and 2001 :

The Influence of Nietzsche's Madness and Dostoyevsky's Horse

Go to Table of Contents of the analysis (which has also a statement on purpose and manner of analysis and a disclaimer as to caveat emptor and my knowing anything authoritatively, which I do not, but I do try to not know earnestly, with some discretion, and considerable thought).

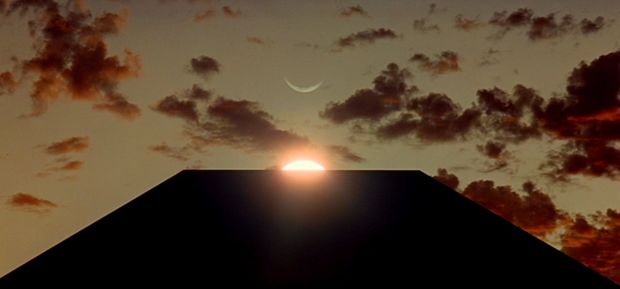

Kubrick uses Richard Strauss' Also Spake Zarathustra during the opening "Sunrise" section in 2001, Strauss' composition inspired by Nietzsche's Thus Spake Zarathustra. A central idea to Nietzsche's work was the eternal recurrence, its inspiration experienced by Nietzsche during a walk when he saw a pyramidal block of stone in the alps at Lake Silvaplana. Wikipedia shows a picture of the stone, and when I look at that stone, its pyramid shape, with the lake beyond, the mountains around, I wonder if it also became an inspiration for the opening of The Shining.

The Nietsche Stone, from Wikicommons.

Compare the pyramidal stone with the pyramid shapes that echo each other center of the composition of the Kubrick's opening shot for The Shining.

The opening flyover of St. Mary lake at Glacier National Park. See the location and how it looks today.

The pyramid shape is found again in the hotel Kubrick chose to represent The Shining.

The Overlook/Timberline with its Snowcat.

There are a few other shots on the internet that show the lake where the stone is situated in Switzerland so that we have expansive watery views backed by snow-covered mountain peaks, presenting a strong parallel with St. Mary lake.

The cyclical, recurring nature of life that Nietzsche proposed appears to have been one locked into a perpetual reconstitution of things so there is no deviation.

What, if some day or night a demon were to steal after you into your loneliest loneliness and say to you: 'This life as you now live it and have lived it, you will have to live once more and innumerable times more' ... Would you not throw yourself down and gnash your teeth and curse the demon who spoke thus? Or have you once experienced a tremendous moment when you would have answered him: 'You are a god and never have I heard anything more divine.'

Also...

"Whoever thou mayest be, beloved stranger, whom I meet here for the first time, avail thyself of this happy hour and of the stillness around us, and above us, and let me tell thee something of the thought which has suddenly risen before me like a star which would fain shed down its rays upon thee and every one, as befits the nature of light. - Fellow man! Your whole life, like a sandglass, will always be reversed and will ever run out again, - a long minute of time will elapse until all those conditions out of which you were evolved return in the wheel of the cosmic process. And then you will find every pain and every pleasure, every friend and every enemy, every hope and every error, every blade of grass and every ray of sunshine once more, and the whole fabric of things which make up your life. This ring in which you are but a grain will glitter afresh forever. And in every one of these cycles of human life there will be one hour where, for the first time one man, and then many, will perceive the mighty thought of the eternal recurrence of all things:- and for mankind this is always the hour of Noon".

That "hour of noon" of which Nietzsche speaks can be seen in the scenes of the monolith's impossible convergence with the sun in 2001.

I have been less concerned with Nietzsche's conception of what all this exactly meant for him than Kubrick's intentions in use and repurposing of the eternal recurrence, for Kubrick's works are all about the conflict of predeterminism (the oracle) and free will, and repetition as found in ideas concerning anemnesis and ZKR. His usage of deja vu, characters often revisiting situations, is all an expression of this, the traversing of the duplicate or similar patterns of a maze or labyrinth in the journey to the center. So, though Nietzsche writes of a locked-in life, and we need to have an understanding of Kubrick's references, Kubrick's use of these ideas must be considered in context of his expression of certain themes throughout his oeuvre and how he played them out.

While I'm here--did Nietzsche believe in the eternal recurrence literally or was it intended as a thought experiment? Some will argue it was a thought experiment. I think he believed in it literally but was a little worried about how this would be received so also gave the option for it to be a thought exercise, and from what I understand personal writings revealed after his death that he did believe in it literally. So I've read.

I could be wrong, but just because Kubrick referenced Nietzsche in his work doesn't mean he was a proponent of Nietzsche's philosophy (if one would call him a philosopher). Kubrick chose to film A Clockwork Orange but he skewers the author, Burgess, in it. Kubrick chose to film The Shining but he has issues with Stephen King's ultimate approach that are evident in the film. Kubrick multiple times represents pre-determinism, a form of the eternal recurrence, as a horrifying and deplorable violence with which his characters wrestle and to which they sometimes appear to willingly submit, such as with Jack in The Shining.

The primate gains the means by which to kill and survive in its meeting with the monolith, which would seem a step toward the "superman", but the Nietzschean tool of the flying bone is answered by the satellites that were originally intended to be nuclear-bearing, humans on the brink of destruction, just as in Dr. Strangelove, which is certainly not a pro-Nietzschean work. Kubrick ended up removing that element but Cold War tension is not excised, however softened with gestures of friendship and appreciation between the Russian and American scientists. War is not glory. War is like a horrible mistake that has accompanied the intellectual evolution promoted by the monolith. The last words said to Bowman, by HAL, as he removes his higher brain functions that make him a computerized version of the "superman", are the lyrics of "A Bicycle Built for Two" in which one individual is "half-crazy" with love for another. When Bowman lands in the hotel room beyond infinity, he is surrounded by paintings that depict courtly love.

Nietzsche may not have been anti-semitic, but with the exception of of some concrete prejudices (racial, and against women), he was nothing if not inconsistent, his ideas passionately at war with one another and he seeming not to be cognizant of the fact. Or it didn't matter to him.

Over time, I have become interested in whether or not Nietzsche's eventual descent into insanity may have influenced in Kubrick in his choice of material and his presentation of HAL's breakdown in 2001, and Jack's madness in The Shining that is undeniably expressed in relationship to an inability to escape repetition through his manuscript being only the same phrase written over and over again.

Nietzsche is said to have broken down upon encountering the abuse of a horse, and in The Shining Kubrick joins a horse with the theme of recurrence, in the form of Colville's painting of the horse racing down the railroad track toward on oncoming train. It deals with destiny and appears in the film after Danny has his first vision.

At walker.org, the post, The Madness Letters: Friedrich Nietzsche and Béla Tarr, describes how Nietzsche, confronting the abuse of the horse, crumbled after an attempt to protect it. He lay in bed mute for several days, then began a letter writing campaign in which he "appoints himself as a figure somewhere between Christ, 'the Crucified', who he had previously criticized harshly for subscribing to the 'ascetic ideal,' and Dionysus, a figure so close to his heart that he often uses 'Dionysian' as a synonym for his famous 'the Will to Power.'" The ascetic ideal is related to what he viewed as man's meaninglessness in facing the void and a "will to nothingness", whereas the creative power of Dionysus, and the "dissolution of boundaries and morality" was the "will to power". The article conjectures, "So his conflation of these two extreme figures, Christ and Dionysus, really puts credence behind the idea that Nietzsche had some sort of psychotic break, a break that allowed him to see such black and white concepts as the same."

Which sounds very much like HAL revealing, during the chess game, that he is seeing from both the black and white POVs of the board.

This is also discussed as Nietzsche's breakdown being due his "full acceptance of his philosophical doctrine", as proposed by the philosopher George Bataille.

The way the story of Nietzsche and the horse is often described, it sounds like he went down only plaintively sobbing over its mistreatment, but a police report instead gave Nietzsche as causing a disturbance, yelling that he was "God come among men" and the "Tyrant of Torino" before falling unconscious.

Malek K. Khazaee writes in The Case of Nietzsche's Madness:

The biggest controversy about his street fall is the famous tale of the cruelly flogged horse, around whose neck the hopelessly sympathetic and tearful Nietzsche had thrown himself in order to protect it, or to protect himself from a sudden fall. This tale seems to be intended to show that Nietzsche had a genuinely kind and gentle nature—the tale that has been exploited optimally by Walter Kaufmann in his relentless attempt to dissociate Nietzsche's temperament from the cruelties of his National Socialist admirers. Lesley Chamberlain takes the tale a step further: "Nietzsche rebelled against human cruelty and crudeness by hugging this horse who was his partner in metaphysical abjectness.... In the case of the horse he had already dreamed the gesture the previous May and written it in a letter[?]... Now in reality some ultimate autobiographical urge made him embrace a real horse, and the shock of willing his own life to the last conscious moment, that momentary exciting flush of power, precipitated his collapse." (Nietzsche in Turin: An Intimate Biography [New York: Picador, 1996], p. 209).

If the above is true, then we have deja vu complicit with Nietzsche's defense of the horse, his dream as a kind of oracle. When he sees the horse being abused does he feel the undeniable force of predestination (eternal recurrence) that urges him to defend the horse? Or does he make a decision to enact that future? We find the same with Danny first seeing REDRUM in a vision and then later scrawling it upon the door, after which he comes out of his near catatonia, becoming himself again.

How much of the story of Nietzsche's horse is apocryphal doesn't matter in respect to how others have already used it or been influenced by it. But it seems the horse wasn't a part of the story until eleven years after the event, and the dream of the horse that Nietzsche had, and wrote about in a letter, does describe an abused horse in winter, and how he had woken in near tears when the cruel coachman urinated on the horse, but I've come across no mention of defense of the horse.

Then there's the possible influence of Raskolnikov's dream of the horse in Dostoevsky's Crime and Punishment. Raskolnikov dreams he is a child again, and in town he comes upon a cart horse being brutally beaten by its owner who declares that the horse is his property. When the boy looks the poor horse in the eye, he himself catches a lash from the whip, becoming in effect the horse. When the horse collapses, dying, the boy throws himself upon the horse's neck, then challenges the horse's owner with his fists, at which point Raskolnikov's father drags him away. When he wakes, his response is,"Thank God, just a dream!...My God! Will I really--I mean, really--take an axe, start bashing her on the head, smash her skull to pieces?" Raskolnikov becomes also the abuser of the horse, not just its protector. Indeed he sees how he is also the father who drags himself away from protecting the horse. He also sees in the dream an oracle of his killing a pawnbroker for her money in an attempt to reverse his destitution. He does, in fact, kill her.

If Nietzsche has been described as mad because he could see opposing POVs, then we have the same with Raskolnikov, but he is an individual who is already described as composed of polar opposites.

How like Raskolnikov is Jack, waking from his nightmare, the horror he has over having chopped his family to pieces, but then succumbing to his hatred, his guilt, and going after them with an axe. With Jack, the mystic in the madness is absent. He doesn't grow in understanding, he shrinks.

We are returned to Kubrick's Fear and Desire in which Private Sidney, the murderer of the captive girl, afterward speaks in a voice like that of the mystic-poet Taliesin who has been and becomes all things.

First we're a bird, and then we're an island. : Before I was a general, and now I'm a fish! Hoorah for the magicians!

There are problems with the characterization of Sidney, whether or not what he does is psychologically true to how he is depicted. He is an individual who flinches away from violence, who the previous night was almost compelled at the gunpoint of his Lieutenant to participate in an encounter with the "enemy", and was traumatized by the violence he had witnessed. The next day, though the lieutenant knows that Sidney is unstable,he leaves him to look after a captive girl, supplying him with his own gun. Sidney presses himself sexually on the girl, then when she attempts to run he kills her. He is already convinced that because he isn't soldier material the lieutenant might abandon him if necessary. We can question if Kubrick and Sackler have built a real character with Sidney or if we have a flimsy sketch that serves to walk some ideas across the screen. We can also say "never mind that for now" and recognize that we have, in Sidney, a character much like HAL, though with his speaking as Taliesin we are called upon to see in his madness a mystical heart. The mystic is shoehorned in there and doesn't fit. But, as far as looking at certain ideas alone, we have to deal with it as if it does fit.

One could say that the woman Sidney kills is Sidney's horse, but Sidney's horse doesn't want him draped around her neck. She just wants to escape. And any compassion Sidney had for the horse has turned into Sidney being also a cart driver who wants something from the horse. The horse runs away. So Sidney kills her because the horse was autonomous and had ideas that differed from Sidney's. Sidney is himself and his opposite, he's a peaceful guy who loathes violence and quickly switches to a lech, and then abandons peace because he's afraid of the lieutenant's disapproval, which is a very simplistic way of handling Sidney. But, alright, he's gone mad and is now the mystic of the group.

I am not and never have been a fan of Nietzsche.

But Nietzsche was certainly a fan of himself and of his own work. The below is clipped from his Ecce Homo in which he expounds on his work Thus Spake Zarathustra, following such chapters as "Why I am so wise", Why I am so clever", and "Why I write such excellent books": People say Nietzsche is spoken of as having humor, and one might wonder if he was joking with these titles, but his writing doesn't suggest this.

This work stands alone. Do not let us mention the poets in the same breath: nothing perhaps has ever been produced out of such a superabundance of strength. My concept "Dionysian" here became the supreme deed; compared with it everything that other men have done seems poor and limited. The fact that a Goethe or a Shakespeare would not for an instant have known how to take breath in this atmosphere of passion and of the heights; the fact that by the side of Zarathustra Dante is no more than a believer and not one who first creates truth—that is to say not a world-ruling spirit, a Destiny; the fact that the poets of the Veda were priests and not even fit to unfasten Zarathustra’s sandals—all this is the least of the matter and gives no idea of the distance, of the azure solitude in which this work dwells. Zarathustra has an eternal right to say: "I draw around me circles and holy boundaries. Ever fewer are they that mount with me to ever loftier heights. I build a mountain range of holier and holier mountains". If all the spirit and goodness of every great soul were collected together the whole could not create a single one of Zarathustra’s discourses. The ladder upon which he rises and descends is of infinite length; he has seen further, he has willed further and gone further than any other man. He contradicts with every word that he utters, this most affirmative of all spirits. Through him all contradictions are bound up into a new unity. The loftiest and the basest powers of human nature, the sweetest, the lightest and the most terrible rush forth from out one spring with everlasting certainty. Until his coming no one knew what was height or depth and still less what was truth. There is not a single passage in this revelation of truth which had already been anticipated and divined by even the greatest among men. Before Zarathustra there was no wisdom, no psychology, no art of speech: in his book the most familiar and most everyday things speak of things as yet unheard. The sentence quivers with passion. Eloquence has become music. Lightning bolts are hurled towards futures of which no one has ever dreamed before. The most powerful use of metaphor that has yet existed is poor beside it and mere child’s play compared with this return of language to the nature of imagery. See how Zarathustra goes down from the mountain and speaks the kindest words to every one! See with what delicate fingers he touches even his adversaries the priests and how he suffers from themselves with them! Here at every moment man is overcome and the concept "Superman" becomes the greatest reality—out of sight, almost far away beneath him lies all that which before has been called great in man. The halcyon brightness, the light feet, the presence of wickedness and exuberance throughout and all that is the essence of the type Zarathustra was never dreamt of before as a prerequisite of greatness. In precisely this space and in this accessibility to opposites Zarathustra feels himself the highest species of all living things: and when you hear his definition of this highest you will realize that his equal will not be found. "The soul which has the longest ladder and can descend the deepest, The most spacious soul that can run and stray and rove furthest in its own self, The most necessary soul that out of desire hurls itself into chance, The stable soul that plunges into Becoming, the possessing soul that has to taste of willing and longing— The soul that flies from itself and overtakes itself in the widest sphere, The wisest soul to which foolishness speaks most sweetly, The most self-loving soul in whom all things have their rise and fall, their ebb and flow"— But this is the very idea of Dionysus. Another consideration leads to this same conclusion. The psychological problem presented by the type of Zarathustra is how he, who in an unprecedented manner says no and acts no in regard to all that which has been affirmed hitherto, how he can remain nevertheless an affirming spirit? How can he who bears the heaviest destiny on his shoulders and whose very life task is a destiny yet be the lightest and the most transcending of spirits—for Zarathustra is a dancer? How can he who has the harshest and most fearful grasp of reality and who has thought the most "abysmal thought" nevertheless avoid taking these things as objections to existence or even as objections to the eternal recurrence of existence? How is it that on the contrary he finds reasons for being himself the eternal affirmation of all things, "the tremendous and unbounded saying of Yea and Amen". "Into every abyss I still bear the blessing of my affirmation to Life". But this once more is precisely the idea of Dionysus.

Read next Nietzsche, The Shining, and The White Man's Burden.

September 2018. Approx 3415 words or 7 single-spaced pages. A 26 minute read at 130 wpm.

Return to Table of Contents for "The Shining" analysis

Link to the main Kubrick page for all the analyses