On Ken Russell's film

A House in Bayswater

The film beginning with a high-rise construction scene, Ken Russell’s A House in Bayswater, which first aired 26 August 1960, creates the impression the documentary will be about a way of living that is about to be torn apart by gentrification, so what is that manner of life and what will be lost? Some reviews state that 30 Linden Gardens, the subject of the documentary, was torn down, but a glance at the map proves 30 Linden Gardens still stands, which may cause the viewer to ask if the movie was about gentrification at all, or was the sense of threatened destruction about how nothing lasts? When asked where the house is located, Russell says in a brief 1960 article on the film (The Kensington News and West London Times 12 August 1960), "In a world of its own just off the main Notting Hill Gate High Street. But you may have some difficulty finding it." Why should we have trouble finding the house when it was a little over one block off Notting Hill Gate High Street and we're given a clear view of it in the film, if this isn't a caution as to being able to locate the world of the bed-sit as expressed in the purported biography, if we're not being told what we view in the film is a matter of Russell's imagination.

As the film continues, it looks like it will be about the individuals who make up the life of 30 Linden Gardens–-David Hurn, a photographer; James Burr, a painter; a “normal” couple, Thomas and Louisa May Laden; Margaret Croft, an elderly woman who worked as a lady's maid for a family in America for many years; a less elderly dancer who studied under Anna Pavlova, Helen May, and one of Helen's pupils. The glue is Elizabeth Collins, the building’s custodian as caretaker of this period of their lives. The subject is an intimate one for Russell, in the news article he is given as having "lived in such a house for five years", this immediately followed by his stating, "I lived there until I married and the place had a lot of atmosphere. So I wrote a script about the house and the people who live in it and the result is this film." So, which is it, did he live in this building or did he live in "such a house"? I've read he lived at 30 Linden Gardens, or is this in error? With the statement that he lived in "such a house", the article does more than project ambiguity. Two of the house's tenants have already made an appearance in Ken Russell's films. Helen May was in his 1958 film, Amelia and the Angel, while Thomas Laden was in the even earlier Peepshow, of 1956, as one of the bogus beggers at the Bogus Begger Academy. Leaning on a crutch, he panhandles for change as a person who once served his country and proves an able actor with his expressive face. 30 Linden Gardens makes an appearance in that film as well, at about seventeen minutes and thirty seconds, the first floor of its facade for some reason covered with evidence of a recent party that has left behind the stragglers of party streamers and a few balloons. I find a comment left on Peepshow on YouTube reveals Ken's "landlady" was in the film--so, at least three of 30 Linden Garden's tenants appeared previously in Russell's films--and I do believe we get a brief glimpse of Elizabeth Collins as a face in a crowd. Then I realize she also appears in Amelia and the Angel as a street-seller of second-hand goods whose small angel wings, attached at her waist, in which she does a little dance, aren't at all satisfactory replacements for the angel wings young Amelia was supposed to wear at her dance recital, Amelia being a young pupil of a dance instructor, Helen May., who had warned her pupils to be careful of their wings but Amelia had secretly carried her wings home and her brother had ruined them. Thus she must find another pair of angel wings to replace them. 30 Linden Gardens was also filmed as the exterior of Amelia's home.

Rather than being a documentary, A House in Bayswater is a work of cinematic poetry. Their relationship to the camera reveals the individuals of 30 Linden Gardens, even if based on themselves, are characters. At one point we are shown the artist painting in his apartment studio and see beyond him, on the mantle, a large vase that holds some flowers. In a voice-over the artist speaks of how, shut away amidst one’s belongings, one creates one’s own world around them, as he is shown turning from his painting, cut and he approaches the same vase on the mantle, and when he picks up the vase and carries it away, we clearly see behind the vase is a painting of it, which hadn’t been there previously, the viewer is unlikely to be aware of this, and the painting of the vase and its flowers is not exact, a demonstration of the difference between artistic expression and the subject. The photographer, taking photos of a nude model (no peepshow) posed in an old bathtub on the balcony, in voice-over speaks of how he wants to use his camera “in the same way as a writer might use a diary, I want to be able to shoot almost by instinct, hoping to bring into pictures my own feelings on the event that I see.” But these are remarks that occur in the midst of other and many bits and pieces and one may not pay attention to how Russell is teaching us to apprehend this work.

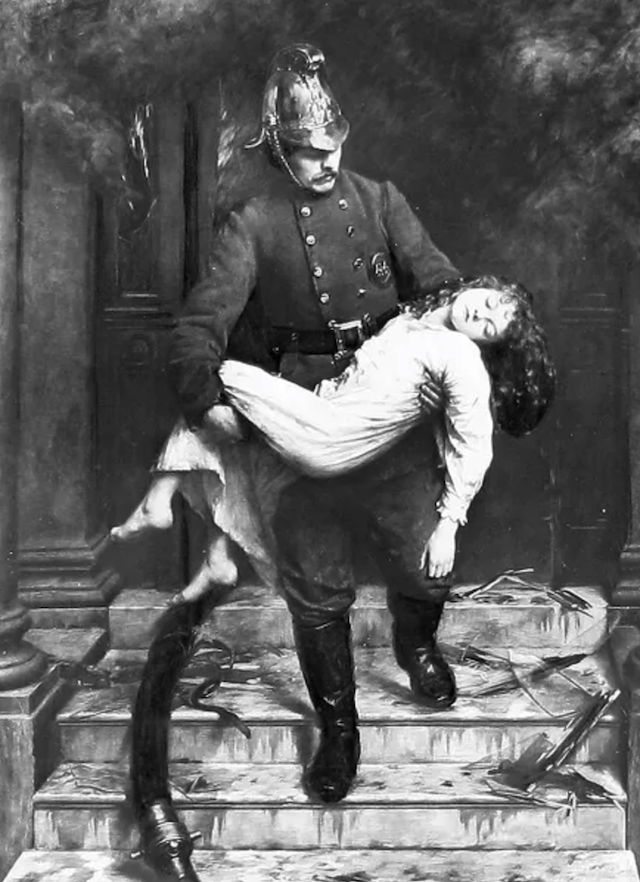

We are about twenty-two minutes into the half-hour long film when Russell has the dancer, Helen May, performing with her young pupil, Anne O. Donoghue, on a theatrical stage. While Anne isn't featured in the film's credits, The Kensington News and West London Times notes, on 16 June 1961, her appearance in Helen May's recital of 10 June and that she was the pupil in The House in Bayswater. Helen gave regular yearly recitals, but I don't see one advertized for 1960 or 1959, which doesn't mean she didn't give recitals those years, I've just not come across news of them. As we aren't shown an audience at the theater, this may not be Russell making a record of a real recital, unless “real” includes being staged for Russell’s camera--and it requires our extra attention. It is Anne’s second performance in the film, her rehearsal for the recital having been previously recorded at the apartment house. One piece she performs is described as from the film The White Moth, of 1924, this history given during a monologue in May’s apartment during which May relates how films used to be preceded by live entertainment, and she was one such dancer who performed the dance of the moth that is warned to keep away from fire and in the end is caught and “sizzled up”. In the movie, The White Moth, that character’s famed dance begins with the dancer emerging from a cocoon that hangs upon a giant rose bush, which Russell alludes to with how the curtain is used on the recital stage in the documentary. In the 1924 film, the moth is chased by a spider and escapes by leaping into a flame, but we are also told in that film (a weak one, there's no real cause to watch it) that the “fire of life is love”. In the documentary, Russell intercuts the recital with the building’s custoridan inviting Tom in for a drink when he pays his rent. She tells him a story, much confused in the editing of it, intentionally so, about a woman named Josephine thrown from a window of the building (perhaps) by a man named McCarty, a woman by the name of Mrs. Paine seeming simultaneously lying dead of a stroke upstairs, and a man, possibly McCarty, then standing on a chair and cutting his throat. Three weeks before all this, she says, a woman had a fire in her apartment in the building. Earlier in the film, the custodian had hung upon the wall a piece of Victorian art which I find is of a theme then popular, a heroic fireman rescuing a little girl from a burning building, but if one is unfamiliar with these paintings one may not catch what the work is about as smoke is only faintly perceived at the top of the painting and there is no fire shown. Thus a theme of fire is developed, though we'll not be aware of this if we've failed to pay attention to the story of the white moth, if we believe it's not worthy of attention because it's the dusty reminiscence of a now irrelevant old woman whose glory days are long past, and if we don't comprehend the painting is of a fireman rescuing a girl. In Helen May’s apartment Russell’s camera had given us a tour of a folding screen upon which were displayed many old photos of her, including one titled “Danse Cymbale, Bacchanalian Dance” and another that touts her as “The World’s Youngest Ballet Mistress”. With Helen, who still loves dance and says she'll not stop until "knocked on the head", we've the persistance of passion as the fire of life, which is as alive in her as it was when she was young, as alive in her though she can no longer move with the muscular stability and balance that she once had. Helen May and Annie are the key couple in the documentary. While the caretaker seems the glue, the elder dancer who is no longer as graceful as she once was, but persists, and her young pupil, who struggles but perseveres, form the heart of Russell’s story. He is determined to wrestle the viewer into respect for their effort and passion, this pair who put themselves on the line when they take the stage. He demands that one connect with them as people.

At the end, a dreamy montage sequence forecasts an inevitable dispersion, which can seem only a lovely bit of nostalgia, not fatally saccharine, which is enough to take away from the film. The caretaker had said she had vetoed plans for a party at the house as the floor would certainly collapse. Now Collins rests after a long day of taking care of the needs of others, she says that she will answer the door under no circumstances after a certain hour. As pounding on the door increases to express intolerable demands, she says even if they knock the door down she wouldn't answer it--and the door comes crashing down to reveal a scene of destruction, as if the house has been wrecked and is being cleared away. The residents of the house are revisited in brief poetic scenes. Anne’s second dance at the theater had been “Victorian Memories” to Richard Strauss II’s “Weiner Blut” Opus 354, and several notes from that sound as the photographer and his model blissfully fall together upon his bed. This is followed immediately by Helen and the girl, in their coats, struggling against a brisk wind filled with balloons and streamers, and if we have watched Peepshow we may recognize the scene in which 30 Linden Gardens's facade was strung with streamers and balloons, or if we have watched The White Moth we may see here the streamers and balloons of the Artist’s Ball in which a life-changing event takes place for the dancer, but if the viewer knows only this film then all they can logically refer back to for an explanation of the streamers and balloons is the threat of a great party crushing the house. Margaret had once described how she had so intensely missed America she'd made arrangements to return, but had then gotten used enough to England again that she was content to revisit America in photographs. While this montage can be absorbed as a metaphor for how nothing lasts so one is left with the satisfaction of memories, Helen carries two pieces of luggage and the girl carries a bag, and to me the sense of uncertain, distressing ends is acute. Russell despised Strauss II for his having worked with the Nazi regime, yet here appears one of his waltzes, to which the girl dances, and the lovers embrace.

As 30 Linden Gardens still stands, a person today may be inclined to believe that the film is a brief biopic that both induces and allays nostalgia. I’ve Russell’s autobiography and he mentions nothing about this film in it, and the 1960 article intimates the house is partly a product of his imagination and says nothing about any threat of it being torn down. We’ve been blown out of many apartments due to gentrification that did leave the buildings intact but renovated for modern appeal that divested the buildings of their 1920s livability, and completely redefined neighborhoods so they became upper middle class and unattainable for former residents. Developers and cities congratulate themselves with the increase of property values. Articles boast of beautification. Russell's film can be about more than one thing--it can be his memorial to a place that exists, in part, only in his imagination, he lived there, he did a lot of creative work there, and this is his honoring of that place. But the story also evinces a real tension of things that fall apart in an untimely way, of lives recklessly torn asunder. Hoping to learn what was actually happening at 30 Linden Gardens, I refer to newspapers and find that Linden-Gardens was in a long and losing fight against gentrification. A 1972 letter to the paper reads, “In witnessing the complete destruction of Linden Gardens over the past few years, it has been heartbreaking to see so many long-standing tenants depart. Permanent residents hold an area together. If the Council is so keen on property improvement, when they give these massive grants for improving the area, why don’t they take a large slice out of the colossal return that these vultures are making and use it to the good of the community, and also insist that the so-called 'Luxury flats' are let at a reasonable, controlled rent?” Other articles reveal not only was the area being transformed into luxury flats but 30 Linden Gardens was by then effectively a hotel. Residential accommodations had disappeared, instead the buildings were largely turned into "hotel accommodation, holiday flatlets, and bed and breakfast accommodation."

Helen May and Anne struggling against the wind of gentrification, luggage in hand, resonates too well with me. This is what happened to the Midtown Atlanta apartment building in which we’d lived for near fifteen years–developers purchased it and people who had been there literally decades were turned out, the building was transformed (not restored) into a "luxury" Airbnb, with a three to four times price increase. Then the apartment complex we lived in after that one was promptly purchased by developers, and though we were supposed to have 120 days to move we were forced out in under 50 days, conversion of the buildings into "luxury" condominiums already beginning while we lived there and our residence torn apart, as had happened at the previous building where though we were still under a lease. My son, having been through two hard gentrifications that meant relocating to different areas of the city, converted his distress into the experimental documentary, The Death of a Home.

I appreciate A House in Bayswater as a piece of art, and I enjoy reflecting on what Russell is saying in it, as well as what was for his fullest understanding and which we'll never access, we only get a glimpse of shadows. The film made me curious about these people and I looked them up. David Hurn, I already knew a little about, he is an accomplished photographer. James Burr, the painter, I discovered had switched to printmaking, a video at YouTube revealing he had a lovely way of talking about his inspirations, possessing an unusually calm demeanor. I found that Helen May had written a book on Pavlova for youth that was well-reviewed in The New York Times on 17 May 1959. I wondered at how Russell's time around Helen May might have influenced his making of The Boy Friend. I considered how he held onto metaphors of The White Moth so that we find a continued exploration of them in later films, such as in Mahler, which opens with a fire consuming the house in which he composed, followed by Alma, his wife, tearing herself out of a chrysalis and kissing a rough sculpture of Mahler's head. And it tears me up that the exact same complaints about gentrification then are the same as had today.

30 November 2024

Return to top of page

Return to the Film Analyses index