Return to Table of Contents for films

Nashville is almost all seeming subplots concerning seeming side characters who confirm that every life is center of a stage but without the script belaboring the point as a mystical revelation. Exempting avant garde cinema, until Nashville, at least as far as I'm aware, the movies that used a story form in which various characters are followed separately, only to have their lives revealed as intertwined in a climactic crisis, tended to be emphatic in the expression of the unique specialness of the entanglement, and the excavations of the histories of the characters and what brings them to a particular place were sharp and clear in the mapping of that especial unity. Nashville busted convention by following 24 characters in a rather abbreviated fashion, but the acreage afforded each of these characters was broad enough that numerous bit players were also highlighted if only through being glimpsed on the set, branches of interaction spiderwebbing in such a way that involvement subtly spread like a virus that retains potency even when far away from its point of nascence. The way dialogue was recorded, multiple conversations rubbing against each other, a sense of audience intimacy is again expanded beyond the key players through their lines seeming to be afforded only a little more gravity in the mix (which isn't the case), so that by the end every nameless face is granted the dignity of a proverbial place at the table, and this despite the movie being conceivably about celebrity. More than any other film I've ever seen, even decades after its release, Nashville is one that embraces every face in the crowd as distinct and remarkable, rather than endeavoring to hide them in a homogeneous mass.

Among the many subplots is the story of Albuquerque (Barbara Harris), aka Winifred, who is determined to get a chance to either become a star or sing in Nashville. We know little about her other than she is determined and that her older, redneck, farmer husband is an impediment. Seizing the opportunity to break free and seek her dream, during a traffic jam caused by a sofa tumbling off a car onto the interstate, she bolts from their bright red pick-up and spends the rest of the movie fleeing him and tinseling the screen with an indefatigable chorus line energy to match the hunger that keeps it fueled. Her husband (Bert Remsen) has himself the peculiar name of Star. It is an Altman mystery, why Star would seek to dissuade another from becoming one. Or maybe not. Maybe it is entirely sensible.

There are many mysteries in this film.

A reason I begin with Albuquerque is, more than any other character, she forges a link to the audience. She is not celebrity. She is not close to celebrity. She aspires and is commanded not to aspire. She is often viewed at a distance, as through binoculars that jitter and dance over her character, so that we do not get close to her. She is akin to someone that you might see when driving around the city, on a street corner here, and then later on another street corner, who becomes familiar and recognizable because she keeps turning up, not because she is a celebrity. She is us. There are other characters who are not celebrities, but as they are given centerpiece treatment in their stories they are distanced from the audience. Albuquerque is, throughout, in a liminal state, her situation always eclipsed and marginalized by the stories of the others.

Though the movie is almost all subplots, it does have two primary focuses. One is a never seen presidential candidate, Hal Phillip walker. His campaign vehicle rolls through the movie broadcasting his views on what's wrong with the country, the bodyless voice reminiscent of the pole-top speakers in MASH occasionally spitting and gurgling a chorus-like commentary on the action. Here, the voice is partly oracular in nature, in as much as it is the voice of the Replacement Party, and the movie is about the assassination and replacement of a celebrity.

“I’m for doing some replacing,” is Walker’s message. “I’ve discussed the Replacement Party…with people all over this country, and I’m often confronted with the statement, ‘I don’t want to get mixed up in politics,’ or ‘I’m tired of politics,’ or ‘I’m not interested.’ Almost as often someone says, ‘I can’t do anything about it anyway.’"

Hal, preaching on how America has gone awry, twentieth century cars more expensive than the jewels that financed Columbus sailing ocean blue in 1492, promises a difference, and throughout the film we see youth campaigning for him with a zeal that shows they see, in the independent politician, revolutionary impact. Yet Walker's campaign conducts itself with lies and intimidation tactics, which the audience may not even associate with Walker as these ways and means would seem to counter the appeal that has infected all these enthusiastic youth. Also, as Walker is never seen, and is never heard in relationship to these activities, it may be difficult to draw a connection between him and his representatives. Our primary point of contact is the intermediary of an out-of-town advance organizer, John Triplette (Michael Murphy) who--despite the fact Walker professes to dislike lawyers and wants them all out of congress--works closely with Delbert Reese (Ned Beatty), a Nashville music studio lawyer, in arranging celebrity Nashville talent to perform at and be a draw for a Walker campaign event. Walker's voice that radiates through the streets from his roaming campaign vehicle does not interact. Triplette, in everything he does, gives himself as Walker's physical proxy.

The other major focus is Barbara Jean (Ronee Blakley), a performer who possesses the kind of stardom Albequerque and many others magnetized to Nashville desire. Very loosely based on Loretta Lynn, despite her youth she possesses the charisma and status of a legend beloved for and by generations, a woman so raw and earnest, open to her fans, and overworked, that every performance sucks the life blood right out of her with the feeding of her audience, the industry, and all who financially depend upon her, including her husband, Barnett (Allen Garfield), who orders her around behind the scenes with humiliating exhortations that everything he does and has her do is for her own good. When she balks, he taunts and tames her with accusations that she is going "nuts" again, which reveals that Barbara Jean has a history of breakdowns that are used to shame her. Though famous, she counts herself as friendless. She has fans at every turn but knows she is hedged about by enemies seeking her throne. Toward the film's beginning, Barbara Jean, having just finished recovering at a burn center from an accident concerning a fire baton, is returning to Nashville, which is a media event due her importance and demands a grand homecoming. Arriving at the Nashville airport, she is greeted by a high school band replete with baton twirlers (even after the accident with a fire baton) and color guard brandishing fake rifles (an anticipation of her death by gun). After she makes a short thank-you speech, when she sees people in the terminal who haven't been permitted on the tarmac, Barbara Jean wonders who they are. The film audience knows many in the terminal are campaigners for Walker opportunistically seeking exposure for their candidate. When Barnett tells her they are fans held back, for her protection, because of hijackers (we should here think of the Walker campaigners and not only of airplane hijackers who made news in the 1970s), she insists upon mingling with them, but then as she makes her way toward the terminal she collapses. The reason is unknown. Perhaps she succumbed to heat exhaustion. The audience can well assume that she is not yet altogether well, but that doesn't account for the manner of her collapse, which is without any warning and is complete. It is another Altman mystery, and the reason for which she spends the bulk of the movie confined in the hospital.

When one compares Barbara Jean's collapse at the airport with her being shot at the Parthenon at film's end, we see how similar these two scenes are. She 's in white at the airport, and falls into her husband's arms. At the Parthenon, she is again in white, and tumbles into a fellow musician's arms at much the same angle. We will return to this scene later for deeper discussion.

At film’s end, when Barbara Jean has been shot at the Parthenon, in the ensuing confusion–celebrities hustling for cover, fans in shock–it's gutsy Albuquerque, the woman who escaped her controlling husband, who ends up with the mic. She faces the audience and, backed by a gospel group, belts out the anthem, "It don’t worry me, it don’t worry me. You may say that I ain’t free, but it don’t worry me."

Unsettling and puzzling. "You may say that I ain't free, but it don't worry me," seems a remark on self-occupied blinders or a unique kind of American nihilism, doesn’t it? And yet we will find it is also a defiant celebration.

Albuquerque, stockings torn and hair disheveled from being on the run, looks nothing like the brunette, ethereal Barbara Jean who wears long, virgin-white dresses with contradictory, sexy, breast-revealing bodices that do more than hint of the priestess. She also looks nothing like Barbara Jean's blond bouffant knockout rival, Connie White (Karen Black), who costumes herself in evening gowns the color of fire and mocks the ability and validity of actresses who don't comb their hair with shellac. How is it that scrappy Albuquerque, a veritable clown in her harlequin-colored skirt, comes out of left field as the next queen of Nashville?

The gentle and country-gentile Barbara Jean touches hearts with plaintive tunes that honor nostalgia, singing of memories of a loving childhood, but the queen is breaking down and Connie White is lined up as her presumed heir. During performance patter that devolves into rambling stream-of-consciousness recollections, we learn Barbara Jean's fond reminiscences of childhood are more complex than her songs allow. She has earned her family's living for as long as she can remember, since she was a child, and is used up, exhausted. Having no personal confidants she can trust, Barbara Jean helplessly turns to her audience for friendship. When Barbara Jean seeks friendship from her audience, her voice begins to fail her, as if she realizes she has overstepped bounds and broken the peculiar trust between the audience and the performer who professionally delivers what the audience has paid to hear. Her part of the agreement has been that she only sings, after all, when she is paid, but she is also invested in a deeply empathetic rapport that is part of her package. And, however loved she may be by that audience, she is expected to fulfill that contract, to deliver that package, so we should consider the nature of that audience-performer love when she sings, "It's that careless disrespect, I can't take no more, baby. It's the way that you don't love me, when you say you do, baby. It hurts so bad, it gets be down, down, down. I want to walk away from this battleground. This hurtin' match, it ain't no good. I'd give a lot to love you the way I used to do, wish I could." We may think first of her husband, and we should think of her husband, but we should think of her relationship with her public as well.

A near polar opposite to Barbara Jean's intimacy, when Connie White tells her fans she's their friend, it becomes a stern warning for them to keep their distance, that she has given them all they are owed and they are to back off. Even if one doesn't care for Connie White, her coolness inspiring little sympathy, she has her walls in place for survival.

Haven Hamilton (Henry Gibson), who is Nashville's king to Barbara Jean's queen, is on stage with Barbara Jean when she is shot. At first oblivious to his own wounds, he cries out that this isn't Dallas, it's Nashville, they won't let this happen in Nashville. The show must go on, as the old saying goes, and flailing about for a willing recipient, demanding, "Sing, sing," he hands the mic to the anonymous Albuquerque.

Though Haven is disoriented, the expression on his face evinces a momentary realization of transference, the passing of Barbara Jean's torch. He looks at Albuquerque almost with an expression of wonder, the woman who fate delivered to him, rather than Connie, who is decidedly absent. He gestures Albuquerque toward the crowd. A non-entity without history. She faces the audience and, after a moment's hesitation that is only the catching of one's breath, revs quickly into this anthem with bold bravado. "It don’t worry me, it don’t worry me. You may say that I ain’t free, but it don’t worry me." It’s a salvation song, the chorus addressing the gods.

Never mind, for the moment, why Connie White isn't on stage to replace Barbara Jean.

Perhaps Albuquerque, via the assurance of Altman's script, opts for this song because it's one, as has been earlier pointed out in the film, that can almost sing itself, an audience can ably carry it on their own. The tune is not one by Barbara Jean, who is part of the old Nashville guard. Albuquerque has previously expressed an interest only in Connie White, pursuing her autograph and hoping to have her listen to one of her own songs, but she doesn't choose a Connie White song, or a Barbara Jean song, and of couse she can't use one of her own as no one would know it. Instead, the song she deploys is a new and near outsider one by Tom Frank (Keith Carradine), of the group Bill (Allan Nicholls), Mary (Christina Raines) and Tom. Their music is considered rock by Nashville, but has just enough of a country-folk-pop flavor that the trio has found a measure of welcome among the country crowd, their sound one that resonates with a younger generation.

Not to be overlooked is the fact that the gospel choir who backs Albuquerque is black and Albuquerque is white, and that black faces are largely absent from the crowd. Altman has already set it up for us to be sensitive to the fact it is a white woman backed by a black choir, for in the film the black choir has been, throughout, fronted by Linnea Reese (Lily Tomlin), a white woman of conservative appearance who seems imprisoned in a loveless marriage to Delbert, the slimey studio lawyer boosting Hal Phillip Walker, but one eventually senses that she may remain in the marriage out of personal choice, due her devotion to her two deaf children, and perhaps other reasons as well that have to do with social standing and societal expectations. Because Linnea hasn't a strong voice musically, we are intended to be aware that her whiteness and privilege have placed her where she is, at the helm of a black choir. What we don't know is how much Linnea may be aware of this, or if she feels that her use of a black choir is giving them voice, just as she tries to create space for her deaf children to be heard. The script takes care to point out that the black choir is stereotyped as closer to our primal roots, less inhibited, and, inarguably, Linnea is provided, by the gospel choir, the opportunity to express herself in a free way we feel may be denied her otherwise, or we could say that she uses the choir as an environment in which she permits herself freer expression. She even sings with them in church on Sunday morning, her husband attending a different church with their children.

The "who" of Linnea, as with many other characters, shifts, if one allows it to do so. As with the other characters, she becomes a person of possible conflicting motivations, the audience not offered enough insight to determine her true feelings. When she has a one night stand with Tom Frank, the womanizing musician who wrote the song, "It don't worry me", she is certainly responding to his invitation to tap and express deeper wells of emotion by breaking further out of bounds. Then she tries out a puff on his post-coital cigarette, he tells her it doesn't look good on her, and she abruptly leaves. We don't know whether that abrupt departure is because she has been reminded of her role as the straight-laced mother and that she must return to it, is obligated to return to it, or if she sees in Tom yet another man who will control her and tell her what to do, what looks good on her. Tom is certainly a womanizer, we have only viewed him as a womanizer, but In Linnea's case we are unexpectedly given room to feel some sympathy for him. He had told her he loved her before she asked for a drag, a confession he repeatedly denies other women, and we get the feeling that perhaps he might be telling her the truth. Is he? Was he telling her the truth when he sang of his love for her at a club earlier in the evening? Or is this part of his womanizing game? At his request, Linnea teaches Tom how to say "I love you" in sign language, which reminds of her interactions with her children, but she ignores his profession of love. Instead, she asks Tom why he smokes. He says it's "easy", just as he had sung to Linnea that he was easy, that he wouldn't put up any fight against her if she wanted him, though lyrically asking her at the same time not to lead him on. Linnea asks for a drag. He tells her it doesn't look good on her. Linnea announces she has to leave--and she does have to leave, one knows this is a relationship that has nowhere to go. She is an older woman with children and he seems childishly, selfishly oblivious to what this means. He responds, while Linnea dresses, by calling a girlfriend and asking her to come down to Nashville. Linnea quickly leaving, they exchange a friendly no-blame kiss goodbye while he is still on the phone, then he hangs up in frustration when she's gone. Perhaps he was only showing Linnea that, just as she has her life to return to, he has his life to return to as well. If his aim had been to injure Linnea with the phone call, she denies him this. She behaves as though she well understands what he is doing in the same way one understands a petulant child and absolves them for their immaturity. Her behavior is also that of a woman whose one night stand was hazarded only because there was no risk of being entangled further emotionally as their "real" lives and her long-standing obligations reside elsewhere.

Linnea is at the Parthenon with the choir when Barbara Jean is shot. So is Tom. If we have disliked Tom, we must then soften the severity of our gaze, for at least a few moments, as he immediately rushes to Barbara Jean's aid and is one of those who carries her bloody body off the stage.

Tom is perceived as an opportunity to experience, for a night, feeling wanted and appreciated as a woman rather than taken for granted as a wife and mother, but there is also a hint of mystery in that Linnea's husband seems already suspicious of her and Linnea is not forthcoming with him. As with the other characters, Linnea is stuck in traffic caused by the sofa incident on the interstate at the film's beginning. When Delbert questions her about her experience of this later, he asks if she was alone, and Linnea ignores his remark, not telling him she was with Opal (Geraldine Chaplin), a woman who claims to be from the BBC, and doing a documentary, but hasn't a camera person with her. Perhaps Del is only controlling and possessive, but when Tom several times calls Linnea at her home to arrange a meeting with her, she denying him the first two times then silently listening the third, Linnea hides from Del it is Tom. She says the first call was from the studio, and that the second call was an anonymous phone stalker. Her husband isn't there for the third phone call, when she only listens to Tom's instructions on how to meet him. We don't know if Linnea initially hides the truth because she wants to meet Tom, or if she hides the truth because she is simply fearful and guarded. We don't know if Delbert is suspicious because she has given him reason to be suspicious, or if Delbert is suspicious because he himself has a wandering eye that his footsteps follow, and we don't know if this is a rare or common occurence.

All these women locked in unrewarding marriages or relationships, maneuvered, controlled, corralled, held subservient, abused by men, and Barbara Jean murdered. One begins to detect a theme.

The word "parthenon" originally meant "unmarried women's apartments"", and in its being used with Athena's temple, a virgin goddess, is believed to at one time have referred to the maidens who served Athena, so it makes sense that Nashville is about women as veritable country music priestesses, and the problem of so many women held captive and seeking escape in one way or another. It is also about women who don't recognize the ways in which they aren't free, or the whys, such as with Sueleen (Gwen Welles), a waitress deaf to the fact she can't sing, who is unwittingly hired to perform a strip tease at a fundraiser for Walker. Surrounded by men calling for her to take off her clothes rather than sing, trapped, then promised a chance to sing with Barbara Jean at the Parthenon if she strips, Sueleen complies. Delbert, who is attracted to her, drives her home. Though she is humiliated and stupefied, he clumsily makes a move on her on the steps of her apartment building, but is interrupted and flees. Wade (Robert DoQui’), an African-American who is not only a friend but a seemingly potential lover, is the one who had seen her being preyed upon and come to her rescue--and we shouldn't neglect the irony of this, that Linnea and Del have deaf children that he doesn't bother to understand but he falls for a tone-deaf singer, that Linnea fronts a black choir and it's a black man who comes to Sueleen's rescue and frightens Del away, and the coincidental parallel that Wade had, earlier in the night, at the club where Linnea had gone to see Tom, bought her a drink then moved along when she proved disinterested (in the book he had gone so far as to test ground by asking if she was married, then when she said that she was he revealed he had been in prison for twenty-eight years, perhaps mirroring her own sense of imprisonment, a conversation that is left out of the film). Sueleen relates to Wade all that happened and he tells her how terrible it is, as if she has not fully absorbed this herself, as if he must be the one to define for her what abuse is because she is unsure herself. The white woman must learn this from the black man because he understands that to which she has been blinded, what she can convince herself is acceptable. Finally, he reveals to her that she can't sing and entreats her to leave Nashville with him. He warns her that Nashville will kill her, tear out her heart and walk on her soul, but she rallies to the lie she's been told, the promise of stardom, and is one of those who is on stage and left paralyzed by the shooting of Barbara Jean at the temple.

Barbara Jean was a woman who could sing and still she was broken.

Connie White doesn't seem like a woman who would be broken. Had she been present on the stage when Barbara Jean is shot, would she have fled, been paralyzed into inaction, or might she have stepped forward and gamely taken the mic from Haven? We'll never know. We'll never know as Haven told Walker's political organizer earlier, "Connie White and Barbara Jean never appear on the same stage together. Connie can replace Barbara Jean, but that's it. As for Haven Hamilton, I'll appear wherever Barbara Jean appears." So it is that Connie White isn't at the Parthenon. Triplette had asked Haven to boost Walker, the payback being that he might get a run for governor out of it. Haven had said he'd think about it and inform him of his decision later. When Haven tells Triplette that he'll appear wherever Barbara Jean appears, he's telling Triplette that if he has Barbara Jean on that stage then he will be there for Walker. Triplette had already been eager for Barbara Jean to appear. He had wanted also to have Connie White. Then it becomes essential Barbara Jean appear, if Haven is to be there, which means that Connie White is shut out of the equation.

One could question why it is essential to Haven that Barbara Jean be at the Walker rally. It may be that the Nashville king and queen must present a unified front.

I don't remember concentrating on the male-female relationships in Nashville when I saw the movie as a teenager in 1975. I recognized them for what they were, yes, but they didn't stand out for me as a subject in the way male-on-female abuse would be highlighted in Altman's Three Women, and not so much because these relationships in Nashville were just typical--so that rather than the film appearing to have, as a theme, the subjugation of women, the inequality was instead received as simply a reflection of societal conventions--but also because the majority of films were by directors and writers whose views of women were stories of subjugation as a matter of course, women viewed as subordinate due the laws of nature and a taken-for-granted hierarchy. Because of this, a male director almost had to go out of the way and yell, "This film is about a societal ill" for mistreatment of women in a film to sometimes stand out as being a revelation of wrong rather than a reflection of the director's bias, and Altman didn't do that. Nor did he do that with Three Women, but Three Women left no room for question.

In the case of Nashville, a woman, Joan Tewksbury, wrote the script, which Altman changed considerably in parts, and the actors tweaked it as well, but we should consider the amount of Joan that is there and its influence on the final film, her perspective on the relationships.

This film, more than being about American politics, more than being about the music industry, more than being about Nashville, is about women, its message deftly transmitted during the airport scene. Though we hear the marching band, Altman gives little screen time to a mix of sexes on the field performing for and receiving Barbara Jean. Instead, we see girls, all these young females split between baton twirlers in sequined, patriotic firecracker colors, and a less decorous but equally patriotic "color guard", its members sporting simulated rifles with which they conduct spinning routines.

As it happens, The Tennessee Twirlers have at least one male member, so it can't be said they are exclusively female.

Eventually, Altman gets around to showing the band that we've been hearing throughout the baton and rifle acrobatics. One can briefly see there is a mix of boys and girls, but Altman chooses to focus on the girls.

Haven has a wife who is off in Paris. He also has a long-time companion, Lady Pearl (Barbara Baxley), with whom his relationship appears to be as a second wife, she even on intimate mother-son terms with Haven's son, Bud (Dave Peel). Lady Pearl's response to the performance is to stress to the media how these highschoolers have practiced two hours every day for a month for the event. Haven breezily, brusquely tells her to shut up in this brief exchange which may even appear humorous. This serves to contrast and thus highlight Haven's later address to the crowd, the stark difference between it and Lady Pearl's addressing the hard work involved. As he takes the podium, he announces, "Did you ever see such pretty girls in your life? Someday you're gonna be big girls

like your mommies, and you're gonna be lookin' for a nice, young, handsome man..."

Whereas Lady Pearl emphasizes the work the girls have put into their performance, Haven responds to them only as potential pretty wives and mothers. When he does so, we understand that Lady Pearl's remarks were in anticipation of how the girls would be routinely received, and an almost desperate effort to swing appreciation to effort. Lady Pearl wants these girls to have opportunities, rather than their worth only calculated in terms of visual decoration, trophies, and caretakers.

This film is about women and their troubled place in society, but everyone in the 70s was thinking of the 60s, of course, with the subject of assassination. Of the Kennedys and Martin Luther King. Of how peculiar, outlier misfits kept seeming to blow in out of nowhere and bloodily mow down leaders who were shifting the hierarchal face of America. In the film, the character of Lady Pearl passionately opines on the deaths of the "Kennedy boys", and Nashville seemed to make sense straight on, the veritable sacrifice of the divine Barbara Jean, in respect of these relatively recent horrors. As Haven says, "This isn't Dallas." But there was more to be had, and that more made the big seem-so assumptions seem too much assumption. One felt to catch what was really going on would be only out the eye’s corner, in the way trickster spirits are glimpsed on the sly.

Nashville is a movie you go see already knowing the plot concerns the assassination of Barbara Jean. Some members of the audience will already be aware of who the killer will turn out to be. Others may not know. Altman doesn't care whether you know or not. Whether you know or not, the movie is a mystery, and Altman presents two likely suspects for the audience to focus upon, ultimately working against stereotype with one and playing into stereotype with the other.

The killer is part of a trio of individuals who circulate around the character of a Mr. Green (Kennan Wynn), and his wife who, like Walker, we never see. The trio is formed of Kenny Frasier (David Hayward), eventually revealed as the assassin, Mr. Green's niece, and a solder, Glenn Kelly (Scott Glenn), whose mother, a dedicated fan of Barbara Jean's, had once lived next to her, had kept a scrapbook on her, and had even saved Barbara Jean's life, rescuing her from a fire, which we assume must have been the baton fire though this is never clarified. Esther Green is ill and in the hospital and because of this Mr. Green becomes acquainted with the soldier, who spends his time at the hospital in vigil during Barbara Jean's recovery after her collapse at the airport. Because Glenn is a soldier, and because his adoration of Barbara Jean is represented in what can be taken as that of a stalker, he is a suspect from the beginning. He is even called out as a killer at the airport, by Tom, because he is a soldier.

Kenny becomes part of the trio circulating around Mr. Green as the Greens run a boarding house and Kenny takes a room there. Kenny seems to have ties to Columbus, Ohio, as he wears a Future Farmers of America jacket that bears the words Columbus, Ohio, which may remind of Walker speaking of Columbus and how new cars now are more costly than the jewels that brought Columbus to America. In the Nashville book, Kenny comes from Terre Haute, indiana, but this is not revealed in the movie. As it turns out, Kenny is in need of a new car, so the Columbus reference on his jacket is a connection to that part of Walker's speech. We first see him during the accident scene concerning the sofa on the interstate. His car has broken down and on its back seat are numerous campaign materials for Walker, so one assumes he is there for the campaign, but we know already there is going to be an assassination, so when we then see Kenny carrying a violin case we wonder if there is a gun inside. This is the movies, violin cases have a somewhat comic history of instead carrying guns in movies, and this character has no reason ultimately to be there other than to be revealed as the assassin. On foot, he makes his way to the boarding house where he rents a room, which he says is like his room at home, and thus becomes caught up in Mr. Green's life. In this way, Kenny serves as a substitute son for Mr. Green, but so too does the soldier who becomes close to Mr. Green, and to whom Green reveals that he and Esther had a son who died in the South Pacific in WWII.

A niece of the Greens, Shelley Duvall as Martha aka L.A. Joan (just as she often changes her appearance in the film, we are informed she has changed her name), has at the same time come to visit with the expected intention of seeing her sick aunt, but she never does. Self-occupied, she is always running off in search of a man to conquer, best case scenario being a musician, her groupie identity tied up in the status of who she lays. The day Barbara Jean is released from the hospital, the unseen Esther unexpectedly dies. The morning after, Green attends his wife's funeral with Kenny. When his niece doesn't show up, Green becomes finally angry and in his fury sets out to find her, to make her pay respect to her aunt who is not a celebrity and has thus not commanded any attention. Kenny protests leaving the funeral but follows him to the Parthenon. Had Martha not skipped the ritual honoring her aunt, the gunman wouldn't have been at the Parthenon when Barbara Jean was singing. Curiously, Shelley's character, who inadvertently brings the shooter to the Parthenon when he accompanies Mr. Green in the search for his niece, is also the only person who ever approaches Kenny's violin case, wanting to see his fiddle. She had done so when he was on the phone talking to his mother, who we are supposed to perceive as controlling and thus the shooting will be commonly interpreted as an act of impotent outrage against her. L.A. Joan, at first glance, seems to have little place in the film but for adding visual quirk via Shelley's outstanding presence and all her costume changes and wigs. Actually, she is a pivotal character, and is associated with the assassin's weapon from the beginning, when we first see her at the airport standing next to the placard that states all persons entering the concourse will be screened for guns and knives, she styled to remind of a revolutionary in her beret and the dark straps crossed over her chest, as if she is porting weapons and munition. She seems intended to remind of revolutionary Che Guevara, perhaps even Patty Hearst, the kidnapped heiress who, under extreme duress, in her captivity became a member of the revolutionary gang that kidnapped her, and was still on the run with them from authorities when the film was released. Hearst, brainwashed and brutalized, had also changed her name, to Tania, inspired by Che Guevara's associate Tamara Bunke Bider who went by the name of Tania the Guerilla. Shelley is of course intended to represent the possibility of armed hijackers, for which reason the checks for weapons. Martha/L.A. Joan may only be a free spirit of a young woman who is careless with her familial responsibilities, not attending her aunt's funeral, but she is the reason that Kenny ends up at the Parthenon, because her uncle is determined she pay respect to that aunt who is never seen, just as Walker is never seen.

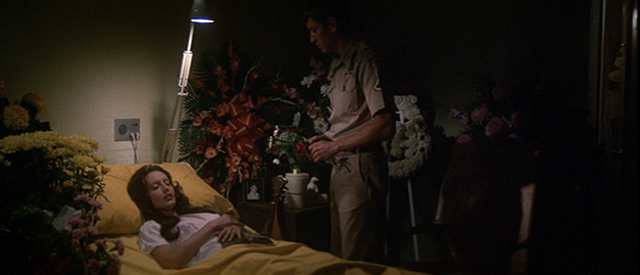

Glenn's mother saved Barbara Jean from the fire, and his stalker-like behavior, which takes him to the hospital where he stays throughout her recuperation, can instead be taken as his continuing a protective guardianship of Barbara Jean after her collapse at the airport. He slips into Barbara Jean's room while she sleeps and keeps watch over her, but as this is uninvited and invasive, we are prompted to wonder if he's a potentially dangerous.

In the hospital room, Kelly watching over Barbara Jean, she already looks dead, surrounded by funereal flowers.

Later, Barbara Jean even complains to her husband about the black flowers that had been sent, it's not said by whom but we might assume they are from Connie White.

If this looks like a death bed scene, it's because it is a death bed scene, Barbara Jean doomed to die.

And yet we are uncertain who was the original target for assassination. Was it the Replacement Party politician, whose face is never seen, who is preparing his speech in his car when the shooting occurs because he and Barbara Jean are not to be on the stage at the same time. Is Barbara Jean the intended victim? The name of the never-seen politician, toward the beginning of the film, is seen together with a Connie White poster, and a joke is made that he looks exactly like Connie White, Barbara Jean’s rival, who Haven has said will never appear on the same stage as Barbara Jean, she can only replace her. This certainly gives fodder for thought. Is meaning intended or not? Also, as Walker is never seen, none of us knows what he looks like, and Altman plays with this by a couple of times presenting a possible face for Walker, this first time being via the Connie White joke.

Barbara Jean was only contracted, by her husband, to play the Parthenon as long as she wasn't associated with Walker, there were to be no political advertisements, and she was to be off the stage before Walker appeared. She adamantly would not boost any politician. When Bertram finds the stage is entirely political, he protests the presence of a huge campaign banner for Walker hanging on the Parthenon, and angrily threatens to pull Barbara Jean from the slate of performers. But he knew, after all, what the concert was for, anyone and everyone at the park that day knows what the concert is for, it is to promote Walter who will also be appearing. Triplette threatens Bertram, in turn, with how bad it will look for Barbara Jean if she fails to perform yet again, for it had only been agreed she would play when she went mentally AWOL at a concert the day before and had to be escorted from the stage, her fans forgetting their compassion for her, booing and tossing litter. So Bertram agrees to have Barbara Jean perform but insists that the chairs for Walker's guests be removed from the stage so it looks less like a rally.

In the realm of heavenly justice, one can look upon Barbara Jean as having fallen victim because she betrays divine laws that frame her essential role, for which reason she dies. She does not belong on that stage boosting Walker. Yet there are others who are also on that stage who had stated they didn't belong there but appeared anyway. When Triplette visits Bill and Mary, hoping to get them to play at the Parthenon, Bill had been immediately for the idea. Mary had wanted to pass, saying they were registered Democrats and couldn't align with Walker. By then, Bill was aware she was having an affair with Tom, and she annoyed him with the comment that Tom wouldn't do it, which is where Altman left the conversation. Yet it is Tom and Mary who end up on stage, while Bill is in the audience. Tom and Mary have, like Barbara Jean's representation, said they do not belong on that stage, but they are there. They are not, however, the high priestess, Barbara Jean, the beloved queen of Nashville who is faltering.

"It's that careless disrespect, I can't take no more, baby. It's the way that you don't love me, when you say you do, baby. It hurts so bad, it gets be down, down, down. I want to walk away from this battleground. This hurtin' match, it ain't no good. I'd give a lot to love you the way I used to do, wish I could."

The tools of art are sometimes remarked upon as being weapons. In Nashville, we at first perceive the assassin as a fake, someone cloaked as an artist-musician who is revealed to be carrying around a gun in an instrument case. But after many viewings of the film one may remember that art has been metaphorically presented as a weapon, and wonder again about that violin case holding a gun in a film where many of the musicians unequivocally maintain they are unconcerned with politics, for which reason some don't mind what stage they play on, while others insist they don't want to be associated with any politician, and yet all the musicians, with the exception of Connie White, and Bill, end up on the stage at the Parthenon. One may also then be reminded of the constitutional division of the secular from the sacred, realize that the musicians, a veritable priesthood, have gathered at the (albeit fake) temple to boost a politician, and wonder about this.

Altman links Lady Pearl with Kenny's gun. We observe her at a club she runs, pulling out a green water pistol when trouble arises after Wade has called out an African-American country singer as being more white than black. As trouble increases she takes the stage, puts up the water pistol, and pulls out a handgun, stating that she has two guns, at which point Altman cuts away from the scene. Later in the film, after Pearl drunkenly relates to Opal the time she had spent campaigning for the Kennedys, and the trauma of their assassinations, Opal tells Triplette she thinks it's people like Pearl and other Americans with guns who are responsible for assassins, stimulating the people who eventually pull the trigger.

There are two wild card characters in Nashville, and Opal is one. Though she purports to be making a documentary, she identifies herself as from the British Broadcasting Channel when it is instead the British Broadcasting Corporation, and she has no camera person with her. She doesn't know who people are, expecting the country singer Tommy Brown to be white when he is instead African-American. Haven's son, Bud, has gone into the business end of things, dues his father's wishes, but would really like to sing, so when Opal asks him to sing for her, he opens up and does so, believing she is sincere, but then a celebrity catches her attention and she goes running off. She states people are friends when they have no memory of her. She attempts to oil gears by asking people if they remember her when it seems they've never met. She sleeps once with Tom and then tells everyone that she and Tom are involved. She bizarrely appears at a graveyard for cars when Kenny happens to be there looking for parts, and happens onto him while she is calling out to the cars if they have any secrets to tell her. She bizarrely appears at a parking lot for school buses where the other wild card character, a magician, has happened to have spent the night. Some people appear to be taken in by her, or are simply polite, while Haven Hamilton has no use for her at all. As she is so false and, quite often, clueless, it's to be questioned if any of her observations can be trusted, so why should we pay any attention when she says it's people like Pearl who stimulate assassins to pull the trigger?

Is Pearl responsible? Does responsibility lie with the fans, who booed Barbara Jean for leaving the stage, compelling her husband to announce they would be able to see her for free the following day at the Parthenon? Is Bertram responsible for agreeing she would play at the Parthenon? Is L.A. Joan responsible, pursuing celebrities instead of honoring personal obligations to the everyday people who are her family? Is Haven responsible, having said he would appear if Barbara Jean was on stage?

Barbara Jean must die. We know this from her collapse at the airport when she ventured forward to see her fans from whom she was being protected. That collapse prefigures her murder. An American Airlines jet passes behind, anticipating the large American flag draped over the facade of the Parthenon. The terminal is filled with Walker campaigners even though the event is the arrival of Barbara Jean. Bertram had insisted the folding chairs at least be removed from the stage of the Parthenon, and when Barbara Jean collapses at the airport it is the moment that Haven Hamilton's son, Bud, enters the screen carrying a folding chair. For what purpose is the chair? We have no idea. But there is one folding chair that remains on the stage of the Parthenon, and it is occupied by Lady Pearl, Bud standling alongside her.

The essential mystery is why Kenny chooses to kill Barbara Jean rather than the political candidate, who we must assume was his original target. Had Kenny planned from the beginning to kill Barbara Jean, he'd ample opportunity at the concert the previous day. He was present, seated beside the soldier and Opal. He listened intently, as though pained, to Barbara Jean sing of wanting to walk away from the battleground of a failed love. In the film, he overhears Opal ask the soldier what it was like in Vietnam, to which Glenn simply replies that it was hot and wet. We have a close-up of Kenny looking up at the pair, as if this is of great significance to him and thus has attracted his attention...

...then he looks at the stage...

...but he's not looking at Barbara Jean, he is instead looking over at Bertram and Triplette on the stage, standing next to Delbert Reese but separated from him, Delbert wearing a Walker campaign button. In the screenplay of the film, published in 1976, after the soldier replied it was hot and wet, Opal had then asked, "Being a trained killer, do you carry a gun?" This isn't in the film, and it would be this line to which Kenny responds so intensely, after which he glances at the men, then Barbara Jean falls apart on stage and Bertram promises she will appear at the Parthenon.

Why does Kenny look at Delbert, Triplette and Bertram rather than Barbara Jean? What has turned his attention to them?

The white pole that separates Delbert from the others and impedes our view of the stage reminds me of an earlier shot in the film. And, again, what we see in the film is slightly different from what is printed in the 1976 published screenplay. At the club, The King of the Road, a famed real-life country violinist, Vassar, invites Connie White onto the stage to sing. In the film, Connie climbs onto the stage which is split, in the camera frame, by a black pole. "That's what I love about this place," she quips. "Can you see me? I can't see you." This isn't in the published screenplay.

While Lady Pearl relates her story of the assassinations of the Kennedys, Connie White introduces Vassar's solo, which is the only time in the film a major Nashville musician is highlighted, and a reason this stands out for me is because he is a fiddler and the person later revealed as the assassin carries his gun in a violin case. Haven is also at the club, in attendance with Triplette. This is when Triplette asks Haven about the possibility of getting Connie at the rally as well, and Haven responds how Barbara Jean and Connie never appear on the same stage together, that Connie might replace Barbara Jean but that's it, and as for himself, he appears wherever Barbara Jean appears.

There are some interesting thematic things going on, concerning visibility, concerning duality, that have everything to do with Connie, the replacement politician, and Barbara Jean. Connie, who has been aligned with the never seen politician, it having earlier been said he looks like her, here questions whether the audience can see her. Then, Haven, while Vassar plays his fiddle, speaks of how Connie and Barbara Jean can never be on the stage at the same time, Connie can only replace her. Later, Bertram insists Barbara Jean can't be on the stage at the same time as the replacement politician, and there are to be no political ads onstage. But Barbara Jean does end up onstage with a huge Replacement Party banner behind her.

There is a point in the film where we think we might have caught a glimpse of the never-seen politician's image. During the highway accident scene, Kenny's overheated car positioned on the side of the road, in the emergency lane, Delbert approaches and asks him to move it down the same path that the ambulance took, and Kenny responds by telling Del to try it. We see heated water explode from his radiator when he removes its cap, which Altman may intentionally recall with Pearl's green water pistol, and the soldier's comment that Vietnam was hot and wet. Giving up on his car, when Kenny goes to take his violin from the back seat we see it situated atop the campaign materials for Walker. We also see a portrait sketch on the case, and because images of politicians often accompany campaign materials for them we may think this picture is of Walker.

Later, we are finally given a good view of the violin and the image and realize it is instead a portrait of Kenny, which seems bizarre, that Kenny would have a portrait of himself on the side of his violin case. When we are finally permitted to view the portrait up close is in front of Walker campaign headquarters.

The film had opened with the Replacement Party van, broadcasting Walker's words, driving out of the Tennessee State Headquarters.

Altman gives us a view of the van returning to headquarters late Sunday night, which is when the faceless Esther dies.

The van enters the garage and the door slides down as the P.A. continues broadcasting Walker's words.

Kenny is shown walking in front of the headquarters as the recording of Walker continues its bland expounding of his views that the churches, with their great land holdings and investments, should be taxed. "No, all will not be easy, but we will bask in the satisfaction of having done what we should have done--and if we don't we may run out of tomorrows."

It is now that we are given a close-up view of the picture on the violin case and see it is not an image of Walker, it is instead a portrait of Kenny.

The Nashville book describes the scene in this way, "The Walker truck drives with its P.A. going to the headquarters garage (known as the Walker-Talker-Sleeper), and goes inside. As the door slides closed, Denny and his violin case, with his self-portrait on the lid, walk by, and look up at the source of the sound." The book thus identifies these exteriors as being the same place, but if we examine the exteriors we'll see that the campaign headquarters that Kenny pauses before is not the same as the one that the truck entered. It only resembles it, and is close enough in similarity that we may not notice it is a different front, especially as the Walker P.A. voice-over continues unbroken between these shots seamlessly binding them together. The second exterior looks very much like Tootsie's Orchid Lounge of that era, a popular music venue, and is the one at which were filmed the interiors that were Lady Pearl's club, in which she seats Kenny at the same table with Bill and Mary, and where, when there had been trouble, she had pulled out the water gun and then the real gun.

The portrait of himself that Kenny has taped to the lid of the violin case is similar to but different from what is used in the opening credits of the film for David Hayward.

To confuse matters a little, the only actor/character, in the opening credits, who is presented with an instrument, is Allan Nicholls, who plays Bill. I know he's supposed to be understood as pictured with a guitar, but his guitar is sized down so that it looks more like a violin.

For a good portion of the film, until the night giving way to the morning of Esther's death, Altman gives us the opportunity to confuse the portrait of Kenny with the never-seen politician. And we know this is his intention as it is only when Kenny is before the campaign headquarters that we are finally shown the portrait and are surprised to find it is of Kenny. A reason I would believe that this particular exterior might intentionally resemble Tootsie's Orchid Lounge, which becomes Lady Pearl's club in the film, is because it is in Lady Pearl's club that we see some political images on the wall, such as a portrait of her beloved JFK. Though Lady Pearl argues that Haven supports no politician publicly, and they donate to all, her club is decidedly political in its decoration.

I've already mentioned how Barbara Jean's appearance at the airport prefigures the assassination scene, with the American Airlines plane in the background, recalled later by the flag, and her collapse as she heads toward the terminal to visit with fans she's been told are kept back because of security to do with hijackers, many of these "fans" instead being Walker campaigners. Altman unites all his characters at the Parthenon at the end, but while some are given almost no screen time at the conclusion, a few others are, as with Barbara Jean, also looped back to connect with the airport. Bill and Mary had arrived at the airport apart from Tom in a scene that leads them past L.A. Joan who is waiting for Mr. Green. Coming upon Delbert and Triplette, who have just met (Delbert at first mistakes an older individual for Triplette), they obstruct Bill and Mary who irritably walk around them. Tom is later seen separately buying cigarettes. L.A. Joan, having been found by Mr. Green and explaining to him she's no longer "Martha", steps away and introduces herself to Tom, hunting an autograph, and does later in the film attempt to pick him up. At the Parthenon, Tom is instead with Mary, on stage, waiting for Bill, who we see in the audience arriving with L.A. Joan. She has played with her appearance throughout, and her brunette hair is now covered with a silver-blond wig, her head also bound up in a turban and a shiny jewel adorning the center of her forehead like a bindi, the effect being less Coachella than a fortune-teller. After the assassination, to L.A. Joan's dismay, Bill leaves her to run up onstage to Mary. In his abandoning L.A. Joan and running to the stage, Bill must push aside a man who blocks him, just as Bill and Mary, at the airport, had to go around Delbert and Triplette, L.A. Joan standing nearby waiting for Mr. Green. At the Parthenon, when Bill pushes the man out of the way to get to the stage, Mr. Green immediately comes across Martha/Joan, grabbing her, but this same man blocks that reunion so we don't see exactly the emotional response of either to it. Altman has returned to the airport scene so that we again have the broken trio, but it's Bill who is with L.A. Joan this time while Tom is with Mary, and L.A. Joan nearby being found by Mr. Green.

This circularity is mentioned in Jan Stewart's book The Nashville Chronicles.

...the city was built in a circle and...people's lives would naturally overlap on a daily basis. That struck a chord with Altman, who, according to Ned Beatty, had once said 'he always wanted to co a movie where someone walks into a revolving door and somebody else comes out and then you to with that person.'

Altman works the revolving door into the end of Nashville, using one of the Parthenon's pillars, in a shot with Delbert (Ned Beatty) and Triplette. After Barbara Jean has been shot and carried away, as Triplette leaves the stage, and the film, for good, he walks behind a pillar, and as he disappears behind the pillar, Delbert emerges from it, rushing back to the stage to get Linnea. One feels the revolving door effect in particular here.

Interestingly, none of the women on the stage at the Parthenon move from it when Barbara Jean is shot. Rushing to Barbara Jean's aid, Tom leaves Mary alone and Bill runs up from the audience to grab her and lead her off. Linnea wanders the stage helplessly until Delbert, who first attended to Haven, returns and leads her away. Though chairs had been ordered removed from the stage except those used by the band, Lady Pearl kept a folding chair in which she was seated, and she is briefly observed forlornly stranded on stage, unable to extract herself even to pursue and help the injured Haven. Bud, Haven's son, who Lady Pearl has clearly doted on throughout the film, isn't around to lead her off as he has helped with Barbara Jean. Lady Pearl is eventually off the stage, but we don't see when or how this happens, if she was assisted off or perhaps walked off of her own initiative, but she doesn't accompany Haven nor does he seek her out. Sueleen doesn't leave the stage at all. Wade was observed earlier in the crowd, his car packed and ready to leave for Detroit, but Altman doesn't return to Wade after the shooting, and with no one to rescue her Sueleen stands paralyzed. Star, too, was earlier shown in the crowd, hunting for Albuquerque, and must certainly see her on stage, but he doesn't pursue her there and Altman doesn't return to him again after showing he's present. So, as regards the two key character women who remain on the stage, after the assassination Altman doesn't return to the men who had been connected with either.

I've read that

Altman's original plan was the assassin would not be revealed. If so, he was prepared to let the audience wonder if the shooter was Kenny or the soldier, perhaps playing as well with the idea that anyone or no one was responsible in this matter of fate.

In Joan's screenplay, the assassin, having shot Barbara Jean, cries out that he could have killed "that Walker bastard" at other times but things kept getting in the way, and he would have killed him the day before but Mr. Green's wife had died. He says, "so this was the right time". That dialogue isn't in the film, and even if it were it doesn't begin to explain why he shoots Barbara Jean rather than waiting for Walker to take the stage and killing him. It does reinforce the idea of an action that was fated to happen. However, seemingly problematic, one could interpret Kenny's words to mean that he does believe he shot Walker. This may remind of Euripides' The Bacchae in which Agave tears apart her own son, believing him a mountain lion, an animal devoted to Dionysus, only to realize that she had killed her son after the madness subsides. Because of the type of details involved, this needs to be interpreted as being an account of the initiate's ritual death and rebirth, participating in the horror and ecstacy of Dionysus-Zagreus' death and rebirth. What concerns me here is that the identity of the initiate is submerged, even all involved, and for the space of the ritual they are something other, not to be recognized as themselves.

Based on the phone call with Kenny's mother, Hayward, who played Kenny, decided that his character had planned from the beginning to kill Barbara Jean, that because of his mother he had resentments against women, and one must admit that Altman sets up the mother-son dynamic so that we are to see Kenny's mother as overbearing and he as weak. Or is that simply a misleading stereotype? The mother, a woman, made the cause of a man's actions? If not overbearing, she could have been represented as one who abandoned her child, and again she would be to blame. Whether or not the audience accepts the mother as the author of the evil that is the assassin, says more about the audience than anything else. She strikes me as a red herring that illuminates a bias when we consider her in context of the other women in the film. As I've previously mentioned, Altman has edited the movie so that Kenny didn't even plan to be at the Parthenon when Barbara Jean was singing, though he knew she would be there. If not for Mr. Green leaving Esther's funeral in order to find L.A. Joan, then Kenny might not be at the Parthenon while Barbara Jean is performing. After we see Kenny tell Green, at the Parthenon, it will be impossible to find his niece, it is Mr. Green who breaks away from him to look for his niece on his own. It's highly unlikely Kenny would have killed anyone in the presence of Mr. Green, and it is not Kenny who leaves Green, it is instead Green who leaves Kenny, after which Kenny turns and approaches the stage, standing next to the soldier by whom he had been seated at the concert the previous day. This is the way it must be so that the soldier will be unable to save Barbara Jean. At the airport, Tom had approached the soldier and asked him if he'd killed anyone that day. Instead, the problem for the soldier is that he is helpless to prevent Barbara Jean's death, when he had been proud of his mother saving her life. Kenny takes this pride away when he slays Barbara Jean, the soldier unable to forestall what has been ordained by fate. It is also as though the gods remind that no mortal can change fate, and that Kenny's mother didn't save her after all. The pride in saving Barbara Jean was a false pride. If Barbara Jean survived the fire, it was due fate, and that her death was not to happen until here, until now. If we are provided with no personal motivation for Kenny, the reason may be that none is needed in case of fate.

One may even see the fated action as approved by Athena, for at the Parthenon, prior to shooting Barbara Jean, Kenny puts on his Future Farmers of America jacket, the centerpiece of its logo being an owl, a bird sacred to Athena, her familiar.

Altman later said that the motive of an assassin is to take advantage of the fame of the person killed and gain as much through the murder. One could interpret Kenny's killing of Barbara Jean then as his understanding she has greater fame than Walker, an entertainer's celebrity has become more important than a politician's. One could interpret this also as underscoring the importance of womanhood in this film, that Barbara Jean is assassinated rather than Walker. But that doesn't entirely account for what happens after Barbara Jean is killed, however we may consider that Barbara Jean is thus positioned to become an unintentional martyr.

Albuquerque sings that no matter the doom and gloom that's preached, no matter how bad things may be, "You may say that I ain't free, but it don't bother me". In respect of Greek tragedy, this is an admission of being in bondage to fate, which is why I state it is a salvation anthem in recognition of and in defiance of the inescapable and god-ordained. Greek tragedy was about the struggle with fate. Destiny decreed and unavoidable. At film's end, as the camera pans up from the Parthenon to the clouds and the sky, one tastes the time between deep history and now, that may feel like a split second. This isn't Athens. This Parthenon is a fake, a replica of a replica. It doesn't matter. Nashville is a direct descendant of ancient tragedy and Barbara Jean was doomed to die. Everyone and no one bears responsibility as all happens according to fate, and yet, despite this, it matters how people choose to act, and Kenny must bear sole responsibility as the individual who pulled the trigger. The gods who have ordained the death are not culpable, instead the blame rests on the mortal who carries out the deed. But Greek tragedy also has every individual functioning as appropriately placed dominos, all their actions working in concert to bring heaven-ordained fate about, so everyone is to some degree complicit.

Are we left then with the pessimism of futility? Is that really what Altman had intended, when all celebrity has fled the stage, and we are left only with the audience's declaration, "You may say that I ain't free, but it don't bother me", led by Albuquerque and, significantly, a black chorus of African-Americans, who are almost certainly each in America because their ancestors were brought over in slavery? One could wonder much gall is had here, that Altman would have them sing this? And yet his camera embraces each of their faces with a care and love and respect that elevates them out of history and the bone-breaking machinery of the powerful that cares nothing for the individual. Celebrity removed from the stage, every person in the chorus is highlighted, becomes real, as with those in the audience on the field. If we are to compare this to any other film of Altman's, it would be his Gosford Park, when the upper class have departed the country estate and all that are left are the servants, and the two sisters who go behind a closed door to support each other in the sorrow they have suffered under the ruling class, one of them having gotten away with the murder of the master of the estate because the authorities are represented as deeming the servants of too little significance to consider as culprits. If, in Nashville, we are left with a chorus and audience that has not been scattered, is not in a panic, the camera visiting one face after another, it is because they are the point of the film, and the anthem of "You may say that I ain't free, but it don't bother me," is not the same as "I'm not free, but it don't bother me". Many have confused "You may say that I ain't free, but it don't bother me", as meaning, "I'm not free, but it don't bother me," which is not the case, and Altman shows us this in the way he visits the faces of the members of the African-American chorus, which is not out of callous privilege. Though this may be a Greek tragedy, taking place on the steps of a borrowed temple, fate as pessimistically interpreted hasn't the last word. Somewhere here is Dionysus, the breaker of chains, who doesn't simply reaffirm life with some drunken revelry that erases cares for the moment, which would only be the feeble art of a worthless charlatan. Instead, somewhere here is Dionysus, the hope of the marginalized, the liberator who brings perfect agape, the breaker of the chain that is the machinery of power, even a conspiracy of destiny that turns into a lie when it is revealed that the chain can be burst.

Afterward

Storyline Coincidence with Pop Culture

The night that Lady Pearl brandishes the green water pistol in her club, we are shown Bill and Mary arguing. Bill is wearing a shirt with a blue print and a blue vest while Mary is in red. Bill complains to Mary that she should be wearing blue, as when he wears blue she is supposed to wear blue. She complains that she doesn't want to dress like twins anymore. Confused, he says they aren't twins, they are a trio, which is when Kenny enters the club. Lady Pearl, calling him a stud (the only character in the film who behaves like a "stud" is Tom), sits Kenny with Bill and Mary so that he, in effect, enacts the third member of the trio, Tom. Kenny is wearing blue. but when he later speaks with his mother on the phone she will fuss at him for having left his blue suit at home. Mary leans in to Bill and says, of Kenny, "He looks like Howdy Doody." A puppet controlled by strings. Coincidentally, in 1948, on The Howdy Doody Show, Howdy Doody went on the campaign trail to run for president. Different stories exist for the timeline of events, but Howdy Doody One (the original puppet), for all intents and purposes, disappeared when he went on the campaign trail, the puppeteer having quit the show and absconded with the puppet as he had learned he wasn't going to receive any funds procured through merchandising the puppet. Because of this, for months, Howdy Doody was absent from the show as there was no longer a Howdy Doody puppet, but the reason given the audience was due his being on the presidential campaign trail. Sponsors complained and Howdy Doody Two was created, which is the one everyone remembers. To explain a change in appearance from the original puppet, it was said Howdy Doody's campaign rival was very handsome and that Howdy Doody had plastic surgery to make him more handsome so that girls would vote for him. It's later revealed that his opponent was his twin brother. I read that the inspiration for Howdy Doody was a caricature of the sister of Buffalo Bob Smith, the co-host of the show, and that she looked exactly like Howdy Doody. Her name? Esther. Which is, also coincidentally, the name of Green's wife, who like the politician is never seen.

In Joan Tewksbury's original script for the film, the Howdy Doody line doesn't occur. Green's wife already, however, had the name of "Ester". So the Howdy Doody connection would seem to be pure coincidence.

Storyline Coincidence with Myth and Legend

I have noted earlier how the logo of the Future Farmers of America that Kenny wears on his jacket bears an owl, and that an owl is Athena's familiar.

Perhaps coincidentally, it is "fire" that finishes its previously interrupted claim on Barbara Jean--the accident with the fire baton, the fire from which Norman's mother saved Barbara Jean--in the form of Kenny, as that name partly derives from a word meaning "fire", and one "fires" a gun. They are at the Parthenon, sacred to Athena. Hephaestus, the god of fire, was the male counterpart of Athena and even married to her. Their son, conceived despite a thwarted rape of Hephaestus on Athena, born of semen spilled on the earth, was Erichthonius, sometimes depicted as half-human, half-snake. The Athena of Parthenos statue shows Erichthonius as a serpent at Athena's feet. Erichthonius may be represented in the film's nameless magician who wears a jacket decorated with a serpent and who seems to serve no purpose in the film except to connect scenes and sometimes precede Walker's campaigning--for instance, he arrives on his three-wheeled motorbike at the airport preceding Hal Phillip Walker's campaign vehicle, and also precedes the Hal Phillip Walker caravan at the Parthenon. When Linnea sees him drive up on his bike at a party at Haven's, she relates to another individual a story about how "Over here at Baptist Hospital, there's a whole ward of young boys, the cutest, best-lookin' boys, you'd ever want to see, paralyzed from the waist down", even as Opal and Albuquerque demount the bike, having received a ride from the magician, Opal telling Albuquerque to "break a leg". This is theatrical jargon, a way of wishing good luck with a performance, but the motorcycle boys paralyzed from the waist down, and the breaking of the leg, could easily allude to Erichthonius, half-serpent from the waist down, who was protected by Athena and said to have introduced sacrifices to Athena at Athens. Another version of the myth has Erichthonius as lame, which is a reason for which he invented the horse-drawn chariot. He was said to have also invented the plough. In the Future Farmers of America logo, the owl sits astride a plough.

All of this could be purely coincidental, but I note it as the assassination/sacrifice occurs at the Parthenon, and the magician, in his snake jacket, is present throughout, standing in the crowd before the stage, a central figure who iis recognized from a distance by his hat.

Barbara Jean, with her accidents connected with fire, the devotion directed her via the soldier, and the abrupt manner of her death, by gun, while she is working, even reminds of the mythical figure of St. Barbara. Kept in an ivory tower with two windows, she changed the two windows installed in it to three, to represent the trinity, which clued everyone in on the fact she was a Christian. For this she was tortured by various means, including fire, but would be found healed every morning. Finally, she was ordered executed by her father, the divine punishment for which was his being struck by lightning. It is because of this that she became the patron saint of artillerymen and those who work with explosives, and venerated by those who are in danger of sudden, violent death at work. Her attributes, a tower with three windows and a lightning bolt, remind of the sixteenth card of the Tarot which pictures two individuals, a man and a woman, falling from a lightning-struck tower that shows three windows, and may signify crisis, sudden change, danger, higher learning, and liberation. Barbara Jean's idolization by the soldier, and her death by gun, fit with attributes of St. Barbara, as well does her sudden death while at work. All of this could be purely coincidental as well, but it's interesting that The Tower card is followed by The Star, the seventeenth card, which may remind of Albuquerque, who desired to be a star, is married to a man named Star, and becomes Barbara Jean's replacement.

January 2019. Approx 12,500 words or 25 single-spaced pages. A 96 minute read at 130 wpm..