The Tease of Hitchcock's Official Marnie Trailer

The Film Up To Mark's First Kiss with Marnie

The Problem of Class and Presence or Absence of Privilege, which Hitchcock Does Confront

The Thunderstorm and the Kiss

How Might Hitchcock Feel About Mark Raping Marnie

The Ties that Bind the Criminal and their Keeper

Hunting the Red Fox

The Killing of Forio

The Tease of Hitchcock's Official Marnie Trailer

Which launches right into the subject of rape in the film, Hitchcock then declining to offer comment as he says he doesn't understand what happens

In Hitchcock's trailer inviting the world to see Marnie, he declares the film difficult to classify, then goes on to propose it is perhaps a sex mystery, but "more than that". He then introduces not first Marnie, the supposed primary subject of the film, the woman who supplies her first-person perspective in the novel by Winston Graham, but Mark, her boss, who after discovering she's stolen from him, hunts her down and marries her.

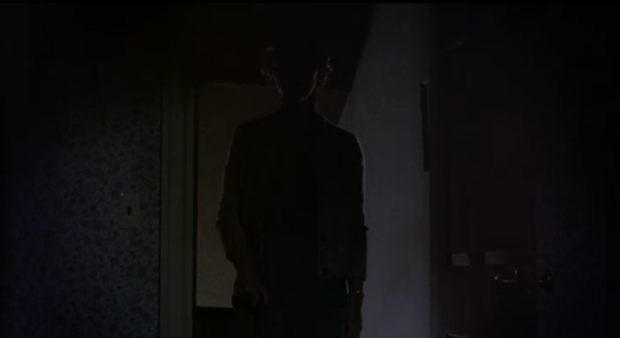

HITCHCOCK: This is Mark, coming down the stairs of his family home outside Philadelphia. He is a thoughtful man, dark and brooding. He is, in a sense, a hunter. And this is what he is hunting. Marnie. Seeing her in her mother's modest house, one wonders how two such different people could cross paths. It was certainly not Marnie's idea. [Cut to showing Marnie stealing money from a safe.] Marnie was going about her own business, like any normal girl, happy, happy, happy. [Cut to Marnie at Mark's office, she upset by a thunderstorm.] Suddenly into this colorful life comes Mark. At first, he didn't know what to make of Marnie. She does seem a rather excitable type. What would account for this strange behavior? Has she just realized she had forgot her umbrella? Marnie's trouble goes deeper than that. Far deeper. And this is the problem which Mark must probe. But first something must be done to calm this girl. Our hero applies mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. But that may give you the impression this picture is all sex and no mystery. Not so at all. [Racetrack. A man speaks with Marnie.] Here, for example, Marnie is speaking to uh I'm not sure who actually, but he is a man from her past, a past she seems to be denying. [Marnie and Mark in a car.] And here is further proof that Marnie is a talking picture.

MARNIE: You don't love me. I'm just something you've caught. You think I'm some kind of wild animal you've trapped.

MARK: That's right, you are. And I've caught something really wild this time, haven't I? I've tracked you, and caught you, and by god I'm going to keep you.

HITCHCOCK: ...[Mark and Marnie in bedclothes in the bedroom of their cabin on a ship.] As for which one is the wild animal, there are times when I'm not sure. [Mark tears Marnie's nightgown off of her.I don't think that was necessary. Actually, I think I should withhold comment since I'm not certain I understand this scene. I shall leave the explanation to your own vivid imagination. It would appear that Mark has a single solution for all problems. This is not so. Mark is a complex man, dark and forbidding. He can also be kind and considerate. And he's also a troubled man. [Marnie rides her horse.] Troubled because he cannot seem to unravel the mystery of the girl called Marnie.

Interesting that the movie is Marnie, but Hitchcock first introduces Mark and focuses upon Mark. No?

The trailer, about 7 minutes long, immediately and almost only flings at the audience the critical Mark and Marnie sex scenes in the movie, of which there are only really two--when Mark kisses Marnie during a thunderstorm, and their first and only coitus during a disastrous cruise honeymoon--so we've just about seen it all, Hitchcock stopping the honeymoon scene in the trailer just before Mark rapes...

Yes, that's right, he rapes his wife. Everyone who has even heard of the movie knows this, don't they? It is one of the big sticking points about Marnie as well as having been one of its big sells. Who is Mark? Never mind who Hitchcock says he is: Philadelphia gentry, dark and brooding, kind and troubled. Sitting in the theater's seats in 1964 we all know full well that Mark is the ultra-resourceful 007, not a Man Who Comes in From the Cold depression case trench coat. He is a debonair gent and womanizer no woman can deny--and Hitchcock doesn't do much to transform 007 into a man of Proper Perennial Old Philadelphian stock who has taken over the family business. In the book, Mark's dark hair is unruly, his complexion so pale he appears ill, he looks bad in business suits but in old flannels he becomes comfortable and even vaguely attractive. That is not 007, and neither is Sean an exact clone of 007 in this film but he is a twin and is sterling glamor. It's assumed every man will be eager to see Sean Connery's irresistible charms be denied by his wife and how he will cope with this, and it's assumed every woman will be eager to have the handsome, decisive, knows-what-he-wants Mark hunting her and eager to win her if even by force. Still, Hitchcock knew that Mark raping Marnie might be a bit of a hard sell, as much as he also knew it would be an attraction. Though the rape occurred in the book, scriptwriter Evan Hunter argued against the scene, saying there was no way the husband could recover audience sympathy after this aggression. I read Hitchcock said he wasn't interested in audience sympathy and the camera was to stay fixed on Marnie's shocked face even as Mark penetrated her. Hunter wrote the scene but kept trying to push an alternative one, confident that Mark would be too compassionate and concerned to ever consider forcing her. So Hitchcock hired a fresh new screenwriter, a woman, Jay Presson Allen, who instead treated the rape as a sometimes problem that occurs in all marriages. Plus, from what I read, she knew not arguing against the rape scene was critical to keeping one's job. Hitchcock wanted that rape scene and so he would have it.

The rape did happen in the book. Was the book wrong in having the rape then attempting to find a way to bring these two together as husband and wife? In the book, after the rape, Mark expresses remorse and makes an attempt to apologize, stating that no man really wants to do that to his wife, that no matter the fantasy it turns out not to be fun (yes, you read that correctly)--but, then he chastises Marnie for having made him do it by not expressing the appropriate gratitude for his love and efforts at helping her. Marnie's horror is actually pretty appropriately expressed, compounded by her aversion to being intimate with anyone, and she feels as though she would gladly kill him next time.

The rape scene in Marnie precedes the 1964 rape ("Oh no, oh yes") of Pussy Galore by Sean Connery's Bond in Goldfinger, but Goldfinger was out in novel form in 1959. The Guardian reports that in a 1959 letter written by Bond creator Ian Fleming to a Dr. Gibson, Fleming revealed his view on Bond's never-take-no attitude as a cure for lesbianism.

Gibson had written to Fleming that while he enjoyed Goldfinger, “although not a psycho-pathologist, I think it is slightly naughty of you to change a criminal Lesbian into a clinging honey-bun (to be bottled by Bond) in the last chapter”.

Goldfinger ends as Bond looks into Pussy’s “deep blue-violet eyes that were no longer hard … He bent and kissed them lightly. He said, ‘They told me you only liked women’. She said, ‘I never met a man before.’” Bond promises her “a course of TLC”, before she looks up at his “passionate, rather cruel mouth” and it comes “ruthlessly down on hers”.

In his June 1959 letter to Gibson, Fleming writes that Galore “only needed the right man to come along and perform the laying on of hands in order to cure her psycho-pathological malady”.

Source: "Ian Fleming: Pussy Galore was a lesbian...and Bond Cured Her", 4 Nov 2015, Alison Flood

Is Marnie lesbian? No. This possibility is never raised in the book or film. She's an individual who has been traumatized and is averse to physical intimacy, another expression of which is the ease with which she lives not letting anyone know anything about herself. Hitchcock makes it clear Marnie has trauma in her past, but he was among those who seems to have defined a woman's resistance to sex as what was termed "frigidity"

After giving it much thought, it seems to me the rape fantasy as a way to break, conquer and win is perhaps intentionally addressed in the book when Mark tells Marnie that the reality of rape turns out to be different from the fantasy. He is obviously shamed by what happened. It may be that the author injected this scene, which does seem out of place with Mark's character overall, as a means and ways to say "this fantasy is wrong". Hitchcock and Allen instead decided that Mark would have raped her as it was part of his dark side and simply not taking no for an answer. But, like Hunter, I don't buy this based on the book's character--which has meant trying to reason out why the author had Mark commit the rape in the book. Ultimately I think it was a misstep on the author's part in his effort to reveal the fantasy as wrong and how it would only compound Marnie's trauma and push her over the edge.

The boundaries between Sean Connery in Marnie and in the 1964 Goldfinger blur for me, though Goldfinger was filmed after Marnie. There's a reason for that, and it's because of how the rape scene is handled with Pussy Galore in the film, and it's not the same as in the Goldfinger book.

Bond said firmly, 'Lock that door, Pussy, take off that sweater and come into bed. You'll catch cold.'

She did as she was told, like an obedient child.

She lay in the crook of Bond’s arm and looked up at him. She said, not in a gangster’s voice, or a Lesbian’s, but in a girl’s voice, ‘Will you write to me in Sing Sing?’

Bond looked down into the deep blue-violet eyes that were no longer hard, imperious. He bent and kissed them lightly. He said, ‘They told me you only liked women.’

She said, ‘I never met a man before.’ The toughness came back into her voice. ‘I come from the South. You know the definition of a virgin down there? Well, it’s a girl who can run faster than her brother. In my case I couldn’t run as fast as my uncle. I was twelve. That’s not so good, James. You ought to be able to guess that.’

Bond smiled down into the pale, beautiful face. He said, 'All you need is a bourse of TLC.'

'What's TLC?'

'Short for Tender Loving Care treatment. It's what they write on most papers when a waif gets brought in to a children's clinic.'

'I'd like that.' She looked at the passionate, rather cruel mouth waiting above hers. She reached up and brushed back the comma of black hair that had fallen over his right eyebrow. She looked into the fiercely slitted grey eyes. 'When's it going to start?'

Bond's right hand came slowly up the firm, muscled thighs, over the flat soft plain of the stomach to the right breast. Its point was hard with desire. He said softly, "now.' His mouth came ruthlessly down on hers.

Well, that's creepy, isn't it, the child aspect. And it's curiously coincidental that in the 1959 book, Galore's reason for not liking men is attached to childhood rape in what is alluded to be a lower class situation in the American rural South, similar to Marnie's terror of sex due a buried childhood trauma (possible sexual assault in the film) that also occurred in a lower class context. However, despite Bond's "ruthless" mouth, in the Goldfinger book there is consent in this scene that uncomfortably closes out the novel. In the film, Galore and Bond fight it out in a barn, each one flipping the other until he wins and she's lying under him. As he lowers himself onto her and kisses her she thrashes about and fights him, and then it changes according to the classic fantasy and she succumbs to his brutal insistence, sexually thrilled and responding to his overpowering her. This is the kind of fantasy that stoked Hitchcock's attack of Marnie, 007's dark eyes boring into her without any trace of affection or love, only communicating dominance. Which is, actually, a fantasy that has also been very often flogged by women as well, such as with the famous scene between Rhett Butler and Scarlett in Margaret Mitchell's bodice-ripper and racist cheeselog, Gone With the Wind. In the book, as in the film, poor, mistreated Rhett decides to squelch all her desire for Ashley Wilkes, the guy she can't have but is a softie, unlike Rhett. Scarlett fights Rhett as he carries her up the stairs to the bedroom and rapes her. She succumbs, finds rapture, finds love, but then the next morning it's back to war. The bad end for this is Scarlett's pregnancy and the embittered and warring Rhett and Scarlett losing their beloved daughter to her falling from a horse. Somehow this would never have happened otherwise, and is a plot point ripped straight out of William Makepeace Thackeray's The Luck of Barry Lyndon, Margaret and many others ignoring how Barry Lyndon is an unreliable narrator who mistreats his wife horribly. A point is that Lyndon is, to a great extent, a construct of his environment, including the harshness of war where he saw rape and murder and torture, and his battling to step up from being the underdog in not only the class war but the imperial impositions of Britain on Ireland. If I include mention of this, it's because class is undeniably a big theme in Marnie, the book and film.

The Goldfinger scene is so altered in the film, from the book, that it makes me wonder if Marnie had an influence.

Boy, that really is creepy, isn't it, Bond saying he's going to give Galore the same kind of TLC they do a "waif" in an orphanage, and she behaving like an obedient child. Damn. Ian Fleming, what the hell was wrong with you?

What is Marnie's Response to the Rape? Does she Experience Rapture and Ride to Heaven on Wings of Devilish Seducing Angels

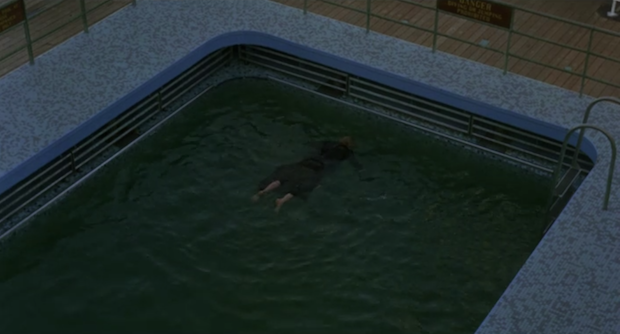

In both the book and the movie Marnie attempts suicide after the rape. In the movie, Mark thinks he's smart and has her all figured out when, after rescuing her limp body from the honeymoon ship's pool and pumping water out of her lungs, he says that had she really wanted to kill herself she would have hopped into the ocean rather than into the pool. A laugh is provided the audience when Marnie retorts she intended to kill herself, not feed the fish, and perhaps they are convinced by Mark she hadn't intended to die, she was only pretending to want to commit suicide in order to scare Mark and keep him at a distance. The fact is, in the book she did attempt to commit suicide in the ocean. She attempted it by swimming out far enough that she would be too exhausted to fight drowning. As we have access to her thoughts in the book, the novel related in Marnie's point of view, we know she really is determined to die. We know what she's thinking, that her intention is to make herself too tired to reflexively fight for her life, and how even when tired she still has to battle her body's determination to save itself from drowning. In other words, her body instinctively fights what it knows is death, just as it has learned to protect itself from dangerous intimacy. Mark rescues her when he realizes what she's doing but has to punch her in the face and knock her out in order to save her life and drag her back to shore. No, don't look for abuse in his knocking her out, it's the only way he can save her, as well as himself, for he's also in peril struggling with her out in the deep ocean. That's very different from the film. Not so amusing. The way Hitchcock portrays Marnie's attempt to drown herself in the ship's pool reminds a bit of Vertigo and Judy/Madeleine's disingenuous attempt at suicide by throwing herself into San Francisco Bay, well aware that John Ferguson will save her.

Hitchcock's first solo directorial effort, the silent film The Pleasure Garden, had an abused native lover of an alcoholic English plantation worker in North Africa wade out into the ocean to drown herself after his English wife shows up. Neither the girl nor the wife knew about one another, and he rejects the girl brutally when the wife appears. The wife sees what kind of a person he is and walks out on him. When the man sees the desolate girl wading into the water, he pursues her, and she thinks he has realized his love for her and come out to rescue her. The way she so happily and enthusiastically turns to him and holds her arms open to him, smiling, one has the feeling the audience is intended to wonder whether or not her suicide attempt was a ruse to gain his sympathy. He drowns her.

Marnie does try to drown herself in the book, so Hitchcock hasn't injected this into the plot, but he has changed it so, as with Judy/Madeleine and the native girl, he wants us to doubt, along with Sean Connery, whether or not she meant to kill herself. Does he mean for us to accept the suicide attempt was not a ruse? The film has many such ambiguities that have no part in the book.

There is nothing amusing about Mark in the novel and very little that is overtly attractive or remarkable about his personality. He's a mystery himself, just as in the film, but the mystery that is Mark doesn't demand attention, and isn't tantalizing in the film for that matter, no matter how suave and debonair he is in the form of Sean Connery, no matter his dark and brooding airs. In the book, with the death of his wife, having returned to civilian life after serving in the Navy during WWII, he's a bit of a ghost trying to fill out the shape of whatever it is he's intended to be by birth, seems not very passionately interested in anything at that point in his life, though he knows about and is interested in a variety of things, such as roses, and is principally guided by a sense of obligation and his dislike for his socially active and engaging cousin, Terry Holbrook, who is a partner in the family business with his father, Mark's uncle. Mark's older brother, who died in the war, was supposed to be the one who took up his family's end of the family business, and was apparently suited to it. Mark, in the book, makes the decision to find a way to save the business while dissociating his family from it, and has managed to do this by the book's end, a favorable effect being he will now have the freedom to find and pursue new interests with Marnie. In the book, Mark doesn't know in the beginning that Marnie is a thief, as he does in the film. He falls in love with her at first sight during the job interview, not knowing why, later saying he thinks love can just happen that way and what matters is how it's nurtured, but he has also believed her story that she is widowed and it's later obvious he comprehends their both being widowed, having experienced loss, as a potential connection between them as they try to make new lives for themselves. Moving over to the book, after seeing the film, it can take a couple of readings to see Mark on this level, and switch from being absorbed by the mystery of Marnie's past to how the book is quite concerned with the effects of death of family members, how death can dramatically transform survivors and the landscape of the future, how individuals cope with loss. This is an important aspect that informs the characters in the book but is absent in the film. Also are absent vital trusting relationships that are in the book. In the novel, Marnie has early lost her father, an infant brother, hate-loves the mother who rejected her, but has an uncle, largely absent because of work, who honestly loves her and treats her well, who wanted to pay for a good education for her as he knew her potential but she ended in only pursuing just enough to get better jobs before needing to get into the work force and support her mother who had become ill. And Mark's widowed mother is actually a very positive presence in the book. She welcomes Marnie, and toward the end she opens up to Marnie and reveals what it was like for her with the depression and emptiness she felt after her husband's death, having to cope with finding a reason to go on, musing about Mark's feelings of failure with having lost his wife at such a young age, significantly his feeling of failure at being unable to keep his wife alive. Hitchcock replaces her thoughtfulness with Mark's widower father who likes horses, cake, tea, people who take decisive action, and plain old animal lust. Hitchcock had been so preoccupied with men with mother problems in The Birds, Psycho, and Vertigo that perhaps he thought it was time to dispense with a man's mother as a problem, replacing the mother problem with a problematic mother-in-law. The film, Marnie, never says anything about Mark's mother. She's a zero.

Now, before discussing the scene of Mark and Marnie's first kiss, I'm going to back up to the movie's beginning and give a brief run-down.

The Film Up To Mark's First Kiss with Marnie

A Woman Who Changes Identities, Like Vertigo But Not

The opening music is at first anxiety-ridden and tortured, then lush and romantic. Back and forth it goes as the anxiety quickly defeats the romanticism and wears it out.

Close-up of a woman in tweed with a yellow handbag held between the crook of her arm and her waist. She walks away from the camera, outpacing it, and we see she is on a platform between passenger trains, no part of her from the rear is not covered--voluptuous head of black hair that is too obviously a wig (though the black is later washed out of her hair), her hands gloved, her legs appearing "nude" but clothed in stockings. She carries also a large suitcase which she sets down as she stops walking.

I feel like I'm watching a parody of a Hitchcock film with this shot, or what might happen if you play one Hitchcock film after another after another, over and over, on an old television on a lifetime of Sunday afternoons, and, chasing each other's tails, they eventually resolve and distill into this one dishonest image that communicates nothing about his work. Which will make it sound like I don't like this film. My relationship with this film is complex, and there's much about it I don't like, but I think Tippi Hedren puts in such a fine performance that in certain respects she saves it, or very nearly does, and there's much that it is stylistically fascinating about the movie.

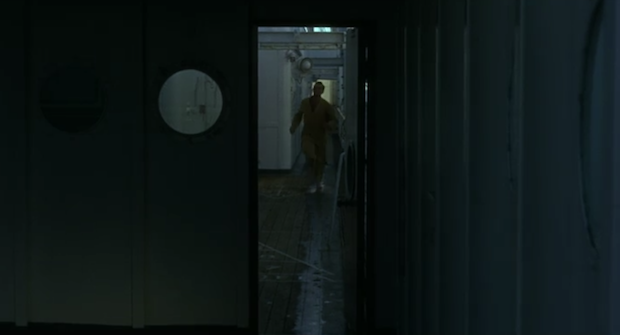

The above, opening shot, however wrong it may feel for some reason, as if Hitchcock is losing his creativity and mimicking himself, yet doing it oddly, is still a significant and important shot to the film. If we're new to the subject of Marnie, we don't know yet her aversion to red, and here she is following a red line. Leaping ahead for a moment, knowing later how red is used in the film to symbolize the trauma that she doesn't remember we can see how the red line expresses how her trauma guides all that she does. After her rape by her husband, the next morning when he goes to search for her on the ship and finds she's attempted suicide, Hitchcock chooses to replicate this line with a shining line of water perhaps left from an early morning swabbing of the deck. We are further, visually reminded of that opening shot with the circular porthole-style window on the door echoing the yellow round of the bag Marnie carries. The relation of the bag to the red line is much the same as the round window to the line on the deck. Mark runs straight down this line as he looks for her, and it is after he follows this particular line that he comes upon Marnie in the pool. I have read that Hitchcock tied water imagery with sexuality, and the author of the book was influenced in his approach to water with having read of individuals who would become obsessed with bathing themselves in order to presumably cleanse themselves of the psychic injury of trauma and shame. Water is long associated with cleansing and rebirth, and in the book Marnie luxuriates in long baths when shedding the persona she had adopted during a job. We have a hint of this when Hitchcock chooses instead to show, at the beginning, Tippi washing black from her hair, like it's ink or paint, which is only symbolic for a hair dye that she would have worn for weeks would not work in this way (besides which she's obviously wearing a wig in the black hair shots). Mark, after raping her, following that line of water, could be an expression of him following that trail of Marnie attempting to either cleanse herself or cover up that red (bloody) trauma.

Cut to a man in a business suit announcing he's been "Robbed!" of $9967. For two detectives, Mr. Strutt describes the suspect, Marion Holland, a female employee, 5 feet 5, 110 pounds, size 8, blue eyes, black, wavy hair, even features, good teeth. Obviously, he had hired this woman out of desire for her and his injury is not only financial but a psychic one, a hit to his pride, his masculine ego, and all those around him are aware of it--the two snickering detectives, his droll, dry secretary who reminds him that he hired Marion without any references at all. As he relates the story, Mark Rutland, a client from Philadelphia, shows up at the door, who boils it all down to his memory of the woman being, "the brunette with the legs". Strutt complains how she was too good to be true, eager to work overtime, never making a mistake, always pulling her skirt down over her knees as if they were a national treasure. She seemed so nice, so efficient. "So resourceful," Rutland remarks in his James Bond accent that has nothing to do with this film.

Back to a close-up on the oblong round of the yellow leather bag clutched under the mysterious woman's arm as she follows a porter to her hotel room. As they turn right down a hall, Hitchcock steps out of a room, closing the door, glancing from her direction back to the camera. Then to a functional, nondescript hotel room with two open suitcases on its bed and a number of new apparel boxes at its foot. The woman places in the smaller suitcase everything she had been wearing, filling the larger suitcase with the accoutrements of her new life--sweaters, green satin slippers, crisp gloves in cellophane. Old shoes, brassiere, slip, go into the other suitcase. Into the new suitcase, from the yellow bag she dumps a quantity of cash. She opens a gold make-up mirror case and chooses from a secret compartment the social security card for the identity to which she's switching--Margaret Edgar. She washes the black out of her hair and throws wet blond tresses back to reveal she's Tippi Hedron. She drops the old suitcase for good in a locker at a train station and goes to stay at the Red Fox Tavern, where she's well-known as Margaret Edgar, and from there to the stable where she keeps her horse, Forio. Carefree and happy, she takes the horse out for a ride.

Then a rather hard cut to a lower-class street scene in Baltimore, down by the docks which is a massive matte painting backing the set, bleak, gray, the focal point being a great ship staring down the street . A yellow cab delivers Marnie to the modest stoop of one of the attached homes. At the next stoop over, several young girls play the "Lady with the alligator purse" jumprope game. A young girl in a plaid dress answering the door at which Marnie arrives, Marnie, desultory, remarks, "Oh, it's you" and asks where her mother is. The girl informs, proprietary, that Marnie's mother is making a pie for her. Marnie responds with some irritation over her mother's affection for the girl.

Some red gladiolas in a vase cause Marnie's vision to be enflamed with red and she immediately replaces the flowers with white chrysanthemums. Her mother chastises her for how she has lightened her blonde hair, that it will look like she's trying to attract men--but it is about the same shade as the blonde hair of the little girl her mother tends. Before the little girl, Jesse, leaves, to reclaim her place in the hierarchy, she gets the hairbrush for Margaret's mother, Bernice, who brushes her hair daily before she returns home. Margaret (Marnie at home) has sat down on the floor with her head on her mother's lap, and her mother pushes her away on the excuse she is causing pain in her leg, but then lets the little girl sit down next to her and lean on her leg and she doesn't complain. It's obvious that Marnie doesn't associate shiny blonde hair with trying to attract men, but with hoping to please her mother just as the little girl's blonde hair pleases her mother. After the girl leaves, Marnie continues trying to secure her mother's affection with a mink scarf she's gotten her and her mother praises her for not having gotten mixed up with men, making her own way. As they prepare the pecans for Jesse's pie, Marnie begs of her mother why she doesn't love her as she loves Jesse, protesting that her mother has always thought there was something wrong with her. Marnie risks bringing up the possibility her mother secretly believes she makes her money off sex as a mistress to a wealthy man, and Bernice violently slaps her.

The slap is so hard that it results in the bowl of pecans dropping from the table to the floor. The effect of it is for Marnie to apologize profusely, however a strained apology. Her mother doesn't say she's sorry. That Marnie's mother slaps her like this may be looked over by some as slaps in film are relatively common, were very common back then, and people have tended to not take very seriously child abuse. And this is Marnie's mother abusing her, using physical violence to silence her, rather than engaging in a conversation, rather than listening to her daughter's emotional injury and trying to connect with her about it. The slap is also significant because of Marnie insisting to Mark later she can't stand to be handled. We don't know yet, when he rapes her, what so deeply troubles Marnie, but we do know that she has been slapped by her mother and we should understand she has at least a history of abuse. No one else in the film is ever physically abused. Marnie doesn't even fight Mark physically. It is only Marnie who endures physical assault in the position of daughter then wife. She endures abuse from her mother when she craves more love from her, asks why her mother doesn't love her, and she endures abuse from Mark when he demands sexual love from her. It's too bad that many will not be disturbed by the slap as it comes from her mother and suggests that Marnie is in "hysterics" when she becomes emotional, demanding some answers from her mother. The slap is an abusive means of control.

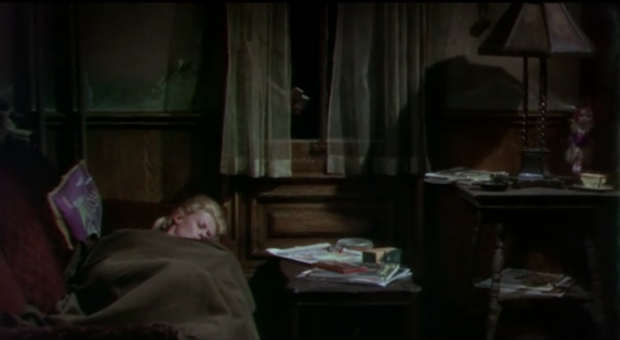

Bernice sends Marnie upstairs to rest. A classic Hitchcock scene involves her mother's dark silhouette in the doorway as she calls to Marnie to wake up from a bad dream she's having, telling her dinner's ready. Marnie wonderingly mentions she hears three taps then when her mother comes to the door is when the cold starts. Her mother doesn't enter the room to help Marnie wake fully from her dream or to console her. When Marnie expresses confusion over the dream, Bernice only turns and taps down the stairs with her cane. Later in the film, when Marnie has a nightmare after having married Mark, he enters the room and tries to wake her by calling to her, but is unable to approach her physically as he has harmed their relationship by having raped her, he is no longer free to console her with touch, and when she opens her eyes and sees him she yells, "Don't", which he could take as her responding to him, when instead she is still deep in her dream. Mark's deceased wife's sister enters, having heard Marnie's continued cries, and the door being open. Lil is no friend of Marnie's but she still has the compassion, puzzled over Mark not waking Marnie physically, to go to her and rouse her. That she does so further highlights Marnie's mother's stubborn disengagement from her daughter and refusal to comfort her.

There is no little girl in the novel who curries Marnie's mother's favor and makes her jealous. Instead, the mother lives with another older woman. The addition of the child not only gives a concrete connection to Marnie's childhood, it introduces the idea that Marnie feels she's treated as though something is wrong with her. Her mother is able to love the other girl, but not Marnie. Why? This is crucial as it means Marnie's mother can indeed express love for others but not her own daughter. She has rejected her. The introduction of the child was a positive.

Next we see Rutland & Co., the establishing shot of it done in the same style as had with Marnie's mother's neighborhood. Very straight, flat city street viewed from slightly above, the camera overlooking a couple of city blocks. Beyond the Rutland & Co. building is a river. There is no port, but it's an industrialized area and the building's relationship to the water is much as the building's in Marnie's mother's neighborhood, this again very obviously studio and backed with a massive painting depicting the river and the city on the other side. Restyled with reddish hair for the new character she now assumes, Marnie is there to apply for a job and only realizes her error, that she's met Rutland previously while working for Strutt, when he enters. Reflexively, she tugs her skirt down over her knees but seems to believe she has not been recognized. She's hired for the payroll clerk job through Rutland's intervention, her prospective superior, Mr. Ward, obviously less inclined because of her lack of proper references.

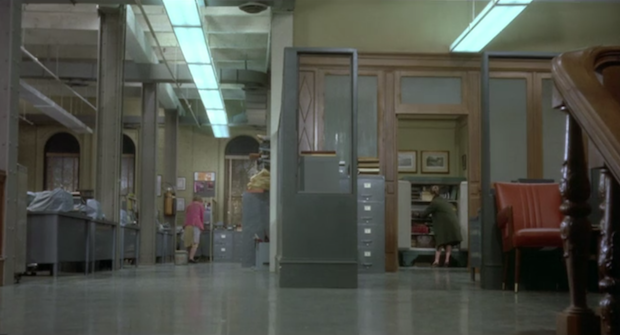

In the book, the problem that Marnie has at Rutland's is that she stays on too long, seven months, because she's enjoying herself, which gives time for people to begin to think too much about her, to question who she is as they naturally want to get to know her. Hitchcock gives some sense of this by making so concrete the Rutland work environment, which is more kinship it shares with Marnie's childhood home. Both have exteriors that are very stagey, theatrical, but the interiors are the most anchoring of any of the sets, feeling very real. Bernice's home gives a very intimate acquaintance with her class, how it is lower but that is her home and she has lavished it with love and pride, enabled by the money Marnie sends her. It is a very personal place, the same as the work environment Marnie shares with her peers at Rutland's. The busy office, the way her peers engage with it and one another, becomes a very personal place through individuals spending the better part of their lives there it being their work home, their work community. It's not a hostile environment, people are friendly, and Hitchcock may have drawn on the book for this, as this is how it is in the book, and one of Mark's principle concerns, when shedding the family business, is making sure that the people who work for the family business are protected and won't experience disruption when the company is absorbed into another.

The Problem of Class and Presence or Absence of Privilege, which Hitchcock Does Confront

The trailer first examines class. Mark is gentry. Marnie is not. Mark's family has a grand, curving swan of a staircase with a red carpet. Marnie's mother has trinkets and a narrow staircase that remind of the back stairs in servant's quarters that are dark because their few windows grant little light. Mark, in both the book and film, is good gentry. In the book he cares about his workers, and his mother does social work improving people's lives. When Marnie brings up class to him as a barrier, he tells her she lives ruled by old-fashioned ideas. The thing is, it's not true that class and privilege don't erect barriers, but Mark isn't sensitive to how they do as he didn't grow up without privilege and doesn't absorb what it means to have privilege. The Mark in the book prefers to be casual and aches not to be defined by a business suit. Enjoyment of the game of exercising power is so much not a part of his psyche is one reason why I took the time, at the beginning of the analysis, to explore why the author would misstep and have Mark rape Marnie in the book. The Mark in the movie obviously enjoys class, consciously understands and enjoys his privilege, and exercises its power. He hunts Marnie. Why? Not because Marnie is a thief, but because Marnie is a thief who has caught his attention by being young, beautiful, and clever.

Without stating as much, despite the friendly tone at the company, the first half of the film frames how many women are employed in labor situations that have low ceilings. There's no path to up and above for the many female secretaries and clerical workers, or the waitresses and hostesses at restaurants. Then, when one is old and frail, what awaits a haggard, bone-weary woman but the job of cleaning, if one isn't so lucky as to be Marnie's mother whose daughter pays for her housing and expenses, and if need be could make some money babysitting for younger, working mothers in the neighborhood, or letting rooms to women with children who haven't a man in the home to help raise them up economically. The first half of the film is filled with women, women, women employed as trusted subordinates but never peers, conflict entering when sexual attractiveness and youth have priority over experience and references. In the trailer, a joke is made about how women are happiest accruing money, Marnie cleaning out the Rutland safe, while what is not shown is that in the film, in the neighboring office area, an aged, solitary cleaning woman sloshes the floor with water from a bucket.

As we view this incredible scene of the offices, Marnie and the cleaning woman each going about their business, side-by-side, separated by mere feet, oblivious to one another, the ostensible tension is will the cleaning woman discover Marnie, but the real tension is that of the young woman who still has, for a time, sex and beauty on her side, adding to her worth, while the older woman, holes in the elbows of her sweater, has nothing left but the desire to get her job done so she can get her aching bones to bed.

It's curious how there's something structurally similar to this shot of the woman swabbing the floors while Marnie cleans out the safe, the opening shot in which Marnie walks the red line of life's choices made by trauma, and the shot in which Mark follows the seeming reflected line of water on the ship's deck to the door from which he'll see Marnie's body floating in the pool. This shot seems different enough from the others, but we shouldn't ignore that strong uninterrupted line of florescent lighting that hangs above the cleaning woman's path, tying this scene with the other two.

Hitchcock, like many White directors of his time, makes no effort to use Black actors, and to a certain extent this reflects the very decided systemic White privilege of the time, reflecting it in the environment of the film, a film that was likely also seen as being targeted for a largely White audience. But it's also a matter of choice. Hitchcock does employ a few Black individuals in the film, and it may be that how they are employed comments on their status. The film is concerned with the place of women, but we see, for instance, an older Black male server at the Red Fox Tavern where Marnie stays when living as Margaret. Then in the scene with the cleaning woman, whose presence Marnie hadn't anticipated, not only does Marnie elude her notice, so too apparently is a Black security guard unexpected who enters the area as Marnie is leaving, they passing close by one another but also unaware of one another because of a wall between them. The Black security guard, in his pressed uniform, engages personably with the cleaning woman, the manner in which he does so revealing to us that she's hard of hearing. Marnie had stuck her shoes in her pockets in order to tiptoe past, and the woman's deafness is why she hadn't heard one of Marnie's shoes drop. It's because the security guard is Black and figures so prominently here that I think we can judge that Hitchcock was deliberately bringing color of skin into this scene that is all about class and privilege and lack of privilege--and then, too, we can look back at the Red Fox Tavern and see how the Black waiter fulfills the same function, for Marnie is only at the Red Fox Tavern by way of having stolen her way up in the world, bypassing concrete ceilings through theft. She would not be a guest at the Red Fox Tavern otherwise, whereas in the book it's at the Old Crown that she stays and enjoys being treated as a lady, her ability to do so also only secured by elocution lessons for which her uncle paid, for it's only in shedding her lower class mannerisms, language patterns and accent that she would be able to also rise through camouflage.

Marnie code switches.

Judy faces the same problem in Vertigo. She was taught the proper elocution and style in order to assume Madeleine's place, but after Madeleine is murdered then Judy is abandoned. When Johnnie finds her and tries to bring her up again out of the class of a shop girl, she dare not use Madeleine's sophistication or shed her accent again for Madelein's upper class one. She tries to get Johnnie to love her for who she is, Judy, the shop girl from Salina, Kansas, but he's only repelled by her. He desires Madeleine's privilege as much as anything.

Hitchcock has said what the audience wanted was glamor, but he desires it as well.

We have seen no Black white collar workers at Rutland's. The Black security guard, in his pressed uniform, and the White cleaning lady, in her bedraggled clothing, further distanced from society by her deafness, are literally after-hours laborers in that they don't mix with the white collar workers, their hours separate from them. Through theft, and having learned how to camouflage her background (though in the book it's remarked upon, with some puzzlement, her etiquette is not always what it would be assumed to be) Marnie has pulled herself up into a place of at least some middle class privilege, and at the Red Fox Tavern even passes for higher. The camouflaged Marnie, stealing, her shoes stuffed in her pockets, treading barefoot, steals past the cleaning woman and the Black security guard, part of whose job is to keep watch and ensure no one steals from the upper class. There's a reason that Hitchcock has situated all three so closely together and Marnie, the payroll clerk, a lower class woman who has camouflaged herself to be a somewhat middle class employee tasked with handling large sums of money, stealing her way past them, her bag stuffed with cash.

In the book, the story placed in England, the low, concrete ceiling is commented on by Marnie when she takes up for Teddy boys who get into fights. She instructs Mark they're not gang members, hard criminals. It's because of their class that they behave as they do, getting into the kind of trouble that they do. They're not dumb, and are desperately aware that where they are in the beginning of their lives is where they will be at the end, that they won't have opportunities to rise and make something of themselves, to even dream of dreams (I'm wildly paraphrasing but that's all right). They're frustrated and blowing off steam.

Marnie's independence, through thieving, solidly remarks on her relationship with the men in power over her who hire her for her youth and beauty and sexuality. She's willing to trade on these assets only so far, and then no farther. She doesn't invite sexual attention. One could hazard that she is taking back from men what they vampirically steal from her, and we haven't even begun to approach the problem of Marnie's childhood trauma and how it contributes to her behavior.

Hitchcock contrasts Marnie's youth and vigor with the older cleaning woman, highlighting how she has assets that will vanish later, but in the trailer he throws a punch at women when he equates Marnie's theft with any normal girl's zeal to happily spend, He characterizes all women as thieves, probably especially in their relationships with men. Did he feel this way or was he only roping in an audience who he believed would respond positively to this joke, and when they were in their theater seats would then be given the opportunity to question these beliefs? By then a very rich man with a considerable amount of power, did Hitch even personally question these beliefs or does he highlight inequities by happenstance? Though Hitch's nature, I read, wasn't to give, it was to hold on to his considerable wealth, not having a philanthropic nature, he did come from a childhood in which he knew what it was to lack, and how privilege thought little of those who had less.

Hitchcock also contrasts Marnie with the one and only woman of privilege in the film, Lil, little sister of Mark's dead wife. She had for some reason grown up in their home and is a young woman who is represented as doing nothing but spending money, socializing, having a good time, being lazy, and waiting for Mark to get over his funereal funk and marry her, she is so easily available after all and always flinging herself at him. Lil does not exist in the book. The woman of privilege is instead Mark's mother, who I've already covered and isn't a threat to Marnie. Indeed, the Marnie of the book scolds Mark for wanting to marry her and bring an unworthy woman like her into the family, fooling his mother who will be glad he's found a new companion in life and that she has a new daughter-in-law. Lil, we will learn, takes the place of Mark's cousin in the book, and not just in the way they wield privilege and take it for granted. In the novel, Mark several times warns Marnie away from his cousin, Terry, and finally demands she stay away from him, which she will not do, not because there is anything between them, there isn't, she just finds him entertaining, a distraction. Plus, he teaches her to gamble, which she finds she is good at, and the gambling aids her in continuing to finance her mother in a clandestine way that doesn't raise suspicion with Mark who doesn't know that she even has a mother. What Marnie isn't good at, as it turns out, is understanding predators who, if they can't get her into bed, appreciate her as a useful tool in other ways. Marnie doesn't at all begin to comprehend yet how brutal the upper class can be peer to peer. She seems a little startled, in the book, at the tension in Mark's extended family, that they don't form a castle-tower unity against the world.

The Thunderstorm and the Kiss

Mark requests Marnie come in and work overtime on a Saturday afternoon. In the movie he does so because he believes he knows who she is, the thief who stole money from Strutt, and plans to bait her. He can't anticipate, of course, the thunderstorm that blows in or the effect the thunderstorm will have on Marnie, but he does know that there are stressors that will set her off, for he has observed how she responded to a drop of red ink on her blouse. It sent her fleeing to the bathroom as if she had been injured.

In the book, this is an important scene as it brings Marnie instead to Mark's house where she observes him away from work, and Mark uses the opportunity to get to know her a little and to introduce her to a little about him, to convivially chat. There is a dramatic, unexpected thunderstorm that takes down a tree, but it doesn't destroy Mark's deceased wife's collection of archaeological artifacts, which are things he enjoys and respects, and when Marnie notices them he's pleased to talk about them and a little about his deceased wife, and asks Marnie about her deceased husband. He doesn't kiss Marnie. Marnie isn't vulnerably alone with him. She meets the housekeeper and the housekeeper is even in and out with the storm, alarmed, making sure Mark's all right, declaring over the damage. Mark does hold Marnie briefly when the storm most dramatically explodes over the house, she colliding with him as she runs, but no sexual advantage is taken. And he eats his words for having tried to solace Marnie's fears of the storm by assuring her that they had almost nothing to fear from the lightning. He was, he admits, very wrong.

Now, one could say that he is acting as a predator employer getting Marnie out to his house, but the book takes pains, over the months that Marnie is at Rutland's, to build a slow feeling out, on his part, of seeing if there might be a mutual interest. The employer predator is explored through Mark's cousin going after Marnie immediately, she rejecting him, and this does cause Marnie to ask co-workers if Mark is the same (to which the answer is no) in order to be aware of what she can expect from him. Based on Marnie's interactions with him, Mark is led to believe, over a period of some months, that she likes him and is attracted to him. He suggests things that she might enjoy doing, she goes and does them, and they casually run into each other. That is how it begins. Mark thinks she's interested. Marnie acts as though she's interested. And Marnie begins to feel guilty because she knows Mark is acting authentically where she is not. For one thing, he is has a dead wife. She does not actually have a dead husband. She is lying to him always. The way she is able to live with this in the book is that she has compartmentalized her life so that the identities she adopts when committing her thefts become their own person, having nothing to do with her. It's not a matter of split personality, she is acting a role that is not her, and when she is done with the role she sheds it completely.

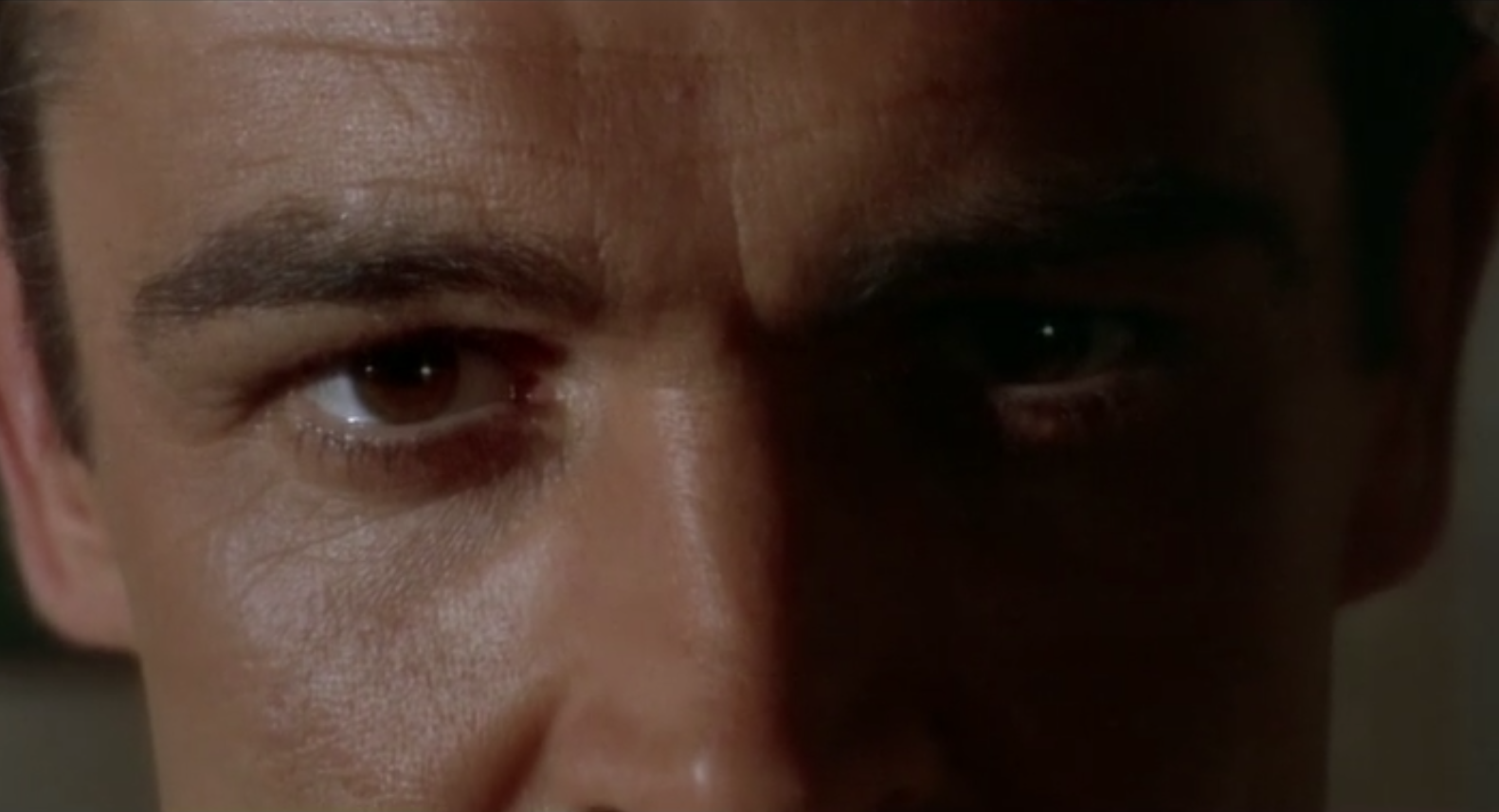

Hitchcock instead arranges a battle of wills between Mark and Marnie, between predators, the chink in Marnie's armor being her PTSD. In his office for the first time, not at his home, instead alone with Mark in a very large and otherwise very empty workplace (Hitchcock makes sure to show us how empty it is, thus stressing Marnie's sexual vulnerability), Marnie is introduced to a little of Mark's personal life. There's a case filled with Pre-Columbian art collected by his deceased wife, who a co-worker had divulged to Marnie had died at 29 of something to do with her heart. Mark reveals that the case holds the only things he has left that belonged to her. Hitchcock also makes a humorous point of Mark's showing off a loving portrait of Sophie, a jaquarundi with fangs bared alarmingly. Mark says he's trained Sophie to trust him.

We may feel the peculiarity of no personal pictures appearing in Mark's office--other than the supposed personal picture of the jaguarundi he had trained to trust him. In many offices, and in almost all films, there's going to be pictures of the spouse, and if there are children there will be pictures of the kids. Instead, Mark has the jaguarundi, and behind him, in the place where we would expect a picture of his deceased wife, is instead the print of a late 19th century painted portrait of a woman.

Curiously, Tippi Hedren and her husband later worked on a film about big cats, in which they lived with lions and, one could say, tried to exercise a similar kind of trust. People were always getting injured. Afterward, Hedren's philanthropy was directed toward caring for big cats. One wonders if this is all pure coincidence, or if she was already interested in big cats, or if Hitchcock might have given her interest a nudge. Big cats were also simply a popular subject. People wanted to save wild things, but people also wanted to tame the wild things they saved.

As it turns out, Mark had once hoped to be a zoologist and the reason he has Marnie there is to type up a paper he's written. In the book, Marnie had brought over to Mark proofs for a very important printing job. There's nothing loaded in that. Hitchcock's Mark goes on the attack with not-so-subterranean hints that he knows she's not trustworthy.

MARNIE (looking at the manuscript she is to type): "Arboreal Predators of the Brazilian Rain Forest."

MARK: Before I was drafted into Rutland's, Mrs Taylor, I had notions of being a zoologist. I still try to keep up with my field.

MARNIE: Zoos?

MARK: Instinctual behaviour.

MARNIE: Oh. Does zoology include people, Mr Rutland?

MARK: Well, in a way. It includes all the animal ancestors from whom man derived his instincts.

MARNIE: Ladies' instincts too?

MARK: That paper deals with the instincts of predators. What you might call the criminal class of the animal world. Lady animals figure very largely as predators.

Whatever Mark had hoped to achieve with this maneuver, tasking Marnie with typing up a paper on predators, using it to allude to female criminal predators, the thunderstorm intervenes and sets off a PTSD response. Marnie panics. At first, Mark watches as if clinically observing, then as the panic becomes worse he rises and comes around his desk to assist. When he does so, we are given a view of the relationship of the portrait of the "tamed" jaguarundi to the rest of his things. It's quite large, wrapped in a sterling silver frame.

Though he tells Marnie the building is safe, a tree branch comes crashing through the window and destroys his deceased wife's case. Having gone to Marnie to assist her somehow, he instead takes the opportunity to kiss her, which she ignores. As far as we can tell, based on Marnie's absolute lack of response to the kiss, she may not have even been cognizant that he'd kissed her. By the end of the film, if one remembers this scene, then one will be aware that Hitchcock has had Mark act similarly to what occurred in an incident that is the source of Marnie's trauma.

In the movie, Marnie's mother is eventually revealed to have been a prostitute visited by sailors when Marnie was young. Remember the big ship looming over the neighborhood, in the matte painting of Marnie's mother's Baltimore neighborhood? Well, in some ways it's a mirage. In the book, where Marnie lived as a young child was on a busy port. In the film, we will later realize that Marnie's mother does not now live in the same place as when Marnie was quite young. While working as a prostitute, when she had clients, Marnie's mother would waker her and have her move out of the bed they shared and onto a sofa in the sitting room. One night, Marnie called out in fear during a thunderstorm, and a sailor came from her mother's bedroom to see to her. The scene is ambiguously presented. He is drunk and whether he might actually intend to molest the girl is unclear. He quiets her, reassuring her, and kisses her neck as she lies back down. This may raise red flags--why would he kiss her neck rather than, say, the top of her head? Hitchcock depicts the scene in such a way that he obviously wants to keep people on the fence about the sailor's intentions. Marnie's mother enters and panics and believes he is molesting Marnie. She attacks him and he falls on top of her when she hits him with a poker, which is how she is lamed, her leg broken. Marnie's mother calls for Marnie's help and Marnie picks up the poker and kills the sailor with it.

What doesn't turn out to happen in the book is any child sexual trauma that has been buried and is hinted at throughout the film. Nor is a sailor killed. In the book, Marnie discovers, after her mother dies, that her father had divorced her mother, the reason he did so being she was engaging in frequent promiscuous sex with soldiers while he was at sea, which she continued to do after their divorce. Her attempt to hide this with a prim and proper facade, saying she was providing Christian companionship for lonely souls (her father, who she stayed home with and tended until he died when she was 33, was a kind of lay pastor, not ordained, severely religious) fails her when she becomes pregnant. She behaves as though the pregnancy doesn't exist up until the time of delivery. Marnie in the house and hearing everything, Edie (Marnie's mother's name in the book) kills the infant after its birth and hides its body under the bed in the room in which she has locked Marnie. She is found not guilty by having been mentally incapacitated by postpartum psychosis. All of this is hidden from Marnie, and her mother, who already had a problem with bonding and expressions of affection, teaches Marnie to reject sex with men and intimacy in general. Everyone knows what Edie did, it was big news, but Marnie, she's been that gaslit by her mother that she had no idea of what happened, and memories surrounding it were denied and buried. When she's young and neighbor children bully her that her mother's a murderer, she doesn't know what they're talking about and can only retaliate with rage in her confusion, fighting them. She is condemned to be an outsider by her family's history.

Marnie also has memories that are securely in place and are terrifying and influential. As for the thunderstorm, an elderly neighbor who took care of Marnie as a child, and later lives with them, frightened her with tales of hell during storms and would give her vivid descriptions of what happened to people she'd seen struck by lightning.

There is no singular trauma in Marnie's past that plagues her. She's a person whose actions can be mysterious as what partly drives her are memories that have been gaslit out of existence by her mother but now subconsciously plague her her daily life so that she lives a certain way without knowing why. As far as Marnie knows, it's just naturally who she is. She was born this way. As for her stealing? She does largely use the money to care of her mother.

Hitchcock changes the trauma so that Marnie has been potentially sexually assaulted in some way as a child--or perhaps not, it may instead have been a misunderstanding--regardless, Marnie killed a man and her mother covered this up and took the blame, then when Marnie forgot about the trauma her mother hid from her that history. He boils a complex history of trauma and abuse down to a singular event that bothers her with fear of the color red, and seeing flashes of red in lightning.

Refer back and consider how Hitchcock has Marnie typing up a manuscript on "Arboreal Predators of the Brazilian Rain Forest" for Mark--and then it thunders, and it rains, and a huge arboreal tree branch crashes in through the window killing what's left of Mark's wife's belongings. Mark's assisting Marnie during her panic in response to the thunderstorm, then kissing her, places him in the position of partly duplicating the scene with the sailor. The tree crashing through the window and crushing the display case must remind of Marnie's mother's fight with the sailor, their falling, and Marnie killing him with the poker, which she remembers as a "stick". Which is a peculiar association for Hitchcock to build, the physical fight that night and the slaying being reflected in the tree that crashes through Mark's wife's case, destroying the artifacts. As for the beating with a stick, in the book there is instead an incident in which Marnie, when she was ten and had thieved a second time and been caught, was beaten severely by her mother for hours with a stick, not stopping until the neighbor woman pleaded that she would end in killing Marnie. The abuse was such that afterward Marnie was left with a permanent indentation on her leg, and is a memory and knowledge that Marnie has always retained.

It's a bad thing to hit a person, such as Bernice slapping Marnie in the kitchen in the film. It's a very bad thing for Edie to have beaten her daughter so severely with a "stick" that she permanently indented her leg. In the book, Marnie's mother is very clearly physically abusive as well.

After the thunderstorm, in the film, Mark picks up one of the pieces of pottery that is still intact, or largely intact, and drops it on the ground. "We've all got to go some time," he says.

When Marnie tells Mark she's sorry about what had happened to the cabinet, he asks why she's sorry. She replies he had said it was all he had left of his wife. He corrects her and remarks, "I said it was all I had left that had belonged to my wife." That's the last time the wife is mentioned in the film. I had assumed it must be meant that what now remains to Mark of his wife is what they shared in their marriage. It's a curious distinction to make and oblique.

A reason it's a curious distinction to make concerns Mark correcting Marnie here as to her phrasing. When Mark had initially spoken of the pre-Columbian art, he'd told Marnie, "Those were collected by my wife. She's dead. The only things of hers I've kept. And that's Sophie. She's a jaguarundi. South American. I trained her...to trust me...that's a great deal for a jaguarundi."

Does the jaguarundi even exist? Marnie, after all, is from the South. Is the jaguarundi only staging?

Marnie innocently remarks that she's sorry about the loss of the cabinet because, "You said it was all you had left of your wife." And he corrects her.

A little later in the film there's another correction in quoting, only this time by Lil, the sister of Mark's deceased wife...who I must keep referring to as the deceased wife as in the film she is an individual who is nameless. (In the book she is Estelle.) Mark has taken Marnie home to meet his father and Lil. Lil is rude with Marnie in an understated but very obvious way. After they've shaken hands, as they sit down to tea, Lil remarks she must have sprained her wrist, and asks Marnie to do the honors, otherwise there will be "droppage and spillage". After, as Mark takes Marnie out to see the horses, he tells Lil that he's sure she's recovered sufficiently to pour Dad another cup of tea. The father gladly welcomes this, but Lil, trying to maintain the story she was injured, declares, "I can't!"

Mark says to her, "When duty whispers low, thou must, then youth replies, I can."

Indignant, Lil replies, "Ratfink! And you misquoted!"

In an age of fops and toys,

Wanting wisdom, void of right,

Who shall nerve heroic boys

To hazard all in Freedom’s fight,—

Break sharply off their jolly games,

Forsake their comrades gay,

And quit proud homes and youthful dames,

For famine, toil, and fray?

Yet on the nimble air benign

Speed nimbler messages,

That waft the breath of grace divine

To hearts in sloth and ease.

So nigh is grandeur to our dust,

So near is God to man,

When Duty whispers low, Thou must,

The youth replies, I can.

The only difference between what Mark has quoted and the poem is that he said, "Then youth replies, I can", whereas it should be, "The youth replies, I can."

I am confident the two misquotings must have to do with one another. Mark says Marnie has misquoted what he said about his wife and corrects her. Then Lil, his deceased wife's sister, corrects him as to the poem and indignantly says he's misquoted.

Lil is supposed to see herself in the lines concerning "wanting wisdom" in an age of "fops and toys". Mark is chiding her for her immaturity and self-centeredness. Ultimately, the poem holds, God-instilled duty compels to answer the call to action.

There is a North/South division in the movie. Whereas Mark's family is from the North, Philadelphia, Marnie's mother and Jesse speak with profound drawls that have nothing to do with Baltimore, but never mind. Try to imagine Marnie with such a drawl, which she has trained out of herself, but Mark will insist he has heard it in how she pronounces "insurance". The first blood spilled during the Civil War was in Baltimore. Maryland was a border state, and secessionists in Baltimore attacked Massachusetts troops who were en route to Washington D.C. Maryland wanted no federal troops moving through the state, and secessionists disabled rail bridges and telegraph lines. Union troops soon occupied Baltimore and it remained occupied throughout the war. If I bring all this up it's because the South and North are at odds in the film, the South representing the lower classes. Marnie only made it as far as she has, up in Philadelphia, by shedding her southern, lower class accent. This is Hitchcock's choice for representing the lower class and upper class English split in the book.

Lil later attempts to get Mark to confide in her what is the mystery concerning Marnie, insisting she will help him, offering her services as "Guerrilla fighter, perjurer, intelligence agent." She reveals she's learned that Marnie has a mother in Baltimore. He, of course, should be suspicious of her intentions, and tries to throw her off the scent. Soon enough, not knowing exactly what's going on but determined to cause trouble and hopefully end up ousting Marnie, Lil swings over to the enemy side and, having learned that something is going on to do with Strutt, invites Strutt to a party where he can meet Marnie and identify her as having stolen from him.

What we principally learn from the exchange is that Mark and Lil are both private preparatory school bred (is he a Harvard man or Yale or Penn, probably Harvard) and possibly Unitarian. That would make sense, and that poor Marnie would be completely outside and bewildered by much of their conversational fodder once they got going. I would think Mark no longer goes to church, but his father might, he's going to enjoy a good transcendental sermon. Can we picture Lil as a Unitarian and a member of LRY (that last part is an in joke)? Or was she raised Episcopalian by her parents, who have disappeared and left her by no means bereft, so maybe they just took permanently off for Italy? Hitchcock is so Roman Catholic he has no conception of how Mark's father could have no acquaintance with the devil except as a literary device.

As for Mark's deceased wife, how she's handled is one of the more peculiar things about the film, that she's treated also in such as a way as to make her a mystery. In the book, Marnie is tasked with emotionally dealing with photographs of Mark's first wife and coming across things that had belonged to her, articles of her clothing. In the film, other than the first wife having been interested in Pre-Columbian artifacts, we know nothing about her, which rather oddly parallels Marnie being a woman without a past--as if a woman without a past is made for taking the place of a woman who is largely treated as not having existed.

Actually, the big thing hanging around that has to do with Mark's deceased wife is her sly little sister who is determined to take her place. Mark was referring to Lil when he made his correction to Marnie. He doesn't have anything left that "belonged" to his wife. But he has Lil. Lil is still around.

How Might Hitchcock Feel About Mark Raping Marnie

There is no denying, in the film, that Mark blackmails Marnie into marrying him, which is to become a captive of Mark's. There is no denying that Mark rapes her on their "honeymoon", though he at first promises he won't press her into a sexual relationship. In one scene, he assures her fate's demand was that she was going to be caught some day, sooner than later, and the result would be unpleasant.

MARK: Eventually, you would've got caught by somebody. You're such a tempting little thing. Some other sexual blackmailer would've got his hands on you. The chances of it being someone as permissive as me are pretty remote. Sooner or later, you'd have gone to jail. Or been cornered in an office by some old bull of a businessman who was out to take what he figured was coming to him. You'd probably have got him and jail. So I wouldn't say you were doing alright, Marnie. I'd say you needed help.

Mark paints for her a picture in which what she has to look forward to is being raped and prosecuted by a less "permissive" boss. Then Mark, having married her, aiding her to escape such a future, believing he is owed the sexual relationship by virtue of marriage, rapes her. His eyes boring into her as he does so speaks to his intention of taming her, dominating her, breaking her. This is explicitly shown the audience, and that Marnie doesn't find rapture in being overpowered and forced to submit. She is frozen, in such shock she is unable to fight. This is undeniable.

So, Hitchcock shows Mark forcing Marnie and Marnie trapped by terror and suicidal afterwards. Mark behaves with Marnie as he has told her another boss would eventually do, a difference being that Mark isn't "some old bull". But does Hitchcock feel what Mark has done is wrong?

Marne's gaze at the camera, at the audience, at Hitchcock through the camera, is stunned helplessness. She can't stop what's happening. She'll at least belong to Hitchcock psychically. Via Mark, Hitchcock drinks up that pain and suffering. She signed a contract, she belongs to him.

Okay, enough of that.

Yes, I believe that Hitchcock could completely believe it was wrong for Mark to rape Marnie, and still try to capture Tippi's soul in the camera and pin her up on the screen in some kind of cinema eternal return zoo where she will experience over and over again his desire, as will he experience her bewilderment at his cunning as his cage closes on her despite her having said no.

Okay, enough of that.

Now, on to the rehabilitation of Mark, who is not a bad guy, but is dark and brooding and troubled, and so in love with Tippi that he would go ahead and rape her by proxy of Sean Connery, the camera and clever editing? Do you see, Tippi, forever and ever, how much Hitch loves you that he would be forced to hurt you this way?

Juli, stop it.

In the movie, Hitchcock then has Mark practice psychoanalysis on Marnie, and will drag Marnie back to her mother's home where she will be forced to confront the truth of her childhood. In the book, Mark instead insists Marnie see an analyst. She does so for a while, then the analyst tells them he thinks he can work with her but only if she agrees to the therapy and is not forced into it. The lesson in the book is, "Don't not only force yourself on someone physically, don't force your way into their mind either. It's dangerous territory. This all must be consensual." Hitchcock didn't get that note.

The Ties that Bind the Criminal and their Keeper

In the book, Mark marries Marnie believing she loves him. In the book, she tells him that she ran off because she feared becoming involved, because of their uneven playing field, he being of a higher class. He honestly believes that she ran off because she loved him. Though she passionately argues that he shouldn't marry her, we are tasked, as readers, to consider that Marnie may actually be in love with him but in this respect is an unreliable narrator as she is confused about all aspects of love and intimacy. Her mother has made her promise to not marry as she can not live with picturing Marnie having sex with anyone, and though Marnie has blocked memories of her infant brother being killed by her mother, during a session with her psychoanalyst she breaks down during a word association concerning childbirth in which he's trying to probe why she is so hostile to the idea of ever being a parent, and we see how she knows but doesn't know. A terrified part of her remembers the birth and the murder of her brother, his being hidden under the bed in the room in which she was locked by her mother, but self-preservation blocks knowledge. Undoubtedly, fear of childbirth would have also its own impact on her fear of sex.

On the honeymoon, when the time comes that she can no longer pretend she might go to bed with Mark, in a desperate plea to get him to stop expecting their relationship to become something more, she blows up and declares she has never loved him, it was all a lie.

"You're not listening to what I'm saying! Don't you understand plain English! I haven't any feelings for you at all. It was all a lie, right from the beginning, first because I wanted to steal the money and then afterwards when you caught me, I had to say something, I had to pretend, so that you wouldn't hand me over to the police. But all the time I was playing up to you, nothing else, nothing! I don't love you. I didn't want to marry you but you left me no way out! Now let me go!"

How like Before the Fact, I thought, reading the above. No, Marnie is in no way like Johnnie in Suspicion (Hitchcok's film based on the novel Before the Fact), a gambler who, on the pretense he loved Lina, a wealthy heiress, may have instead married her for her money. But I considered how Hitchcock, reading Marnie's outburst, must be reminded of Johnnie's outburst in Before The Fact, which wasn't included in the film, it having occurred when Lina confronted him with the knowledge he'd had an affair. In the novel, she had long suspected he was a thief, a con man, but over time she had become accustomed to hiding this about him, to not confronting this about him, believing he couldn't control himself. She excused all this, believing he loved her madly and was faithful to her.

Johnnie pushed his hands a little deeper into his pockets and grinned at her cruelly. "Yes, I think it's about time you had a few home truths too, as we're going in for home truths this evening apparently. And after all, I'm getting a bit sick of smarming to you for your damned money that you're so mean with. I'm afraid, my dear, I never really cared two straws about you. After all, I do like my women to be pretty. But I took you in all right, didn't I? Good Lord, your people knew well enough what I was after. But you were so conceited, you never guessed. Really, my dear girl, what use do you think a woman like you would have been to a man like me, without your money? I believe you're under the impression that you've been what they call 'a good wife' to me? Well, all I can say is I'd sooner have a wet fish in my bed. Look what you were like on our honeymoon! Spoilt the whole thing. If you can forget all that, I can't. I promise you, if I've played about a bit, you've driven me to it..."

Marnie immediately feels guilty for what she had said to Mark, not all of it being true, seeing how she's hurt him, but she's desperate to make him hate her, hopeful he will leave her alone. Johnnie, instead, luxuriates in what he's told Lina. The rest of the book is a lesson on why Lina leaves but returns to him, Johnnie pleading (when he needs money) that he hadn't meant at all what he'd said, and then Lina resigns herslf to staying with him and even to the possible eventuality that he will kill her.

Subconsciously it influenced all her thoughts, and most of her actions. The feeling that she and Johnnie were cut off from the rest of the world had now become natural to her. Other people did not know it, but she did, and took it for granted. It no longer distressed her, really. It just meant that Johnnie was not responsible for what he did and she was his keeper, with a trust that she must never relax for an instant; and no one else must ever, ever know anything about it.

The paragraph above could very easily be replaced with what Mark tells Marnie, in the film, after he has caught her stealing, before he blackmails her into marrying him.

MARK: I can't let you go, Marnie. Somebody's got to take care of you and help you. I can't turn you loose. If I let you go, I'm criminally and morally responsible.

What ties Lina to Johnnie is more complex than this, but she has come to feel criminally entangled with Johnnie's crimes, because of her having become aware of them.

Mark's claim that he can't turn Marnie loose as that would make him criminally and morally responsible is not in the book. It's an idea that fits well into Marnie, but it takes me back to Suspicion. These are two very different books, and Johnnie is very different from Marnie, and Mark is very different from Lina. When Mark learns eventually how Marnie had stolen a not insubstantial amount of money over several years time, knowing it is going to catch up with her he is desperate to find a way to confront these crimes with her, but somehow keep her out of jail. He's not confident that simply paying her former employers back will do the trick.

Hunting the Red Fox

In both the book and the film there finally happens a catastrophic, semi-climactic fox hunt, but what occurs in the book is far different from the film. In both, the fact that Marnie will have to face a day of reckoning concerning her thievery is quickly becoming apparent. In the book, during the fox hunt, seeing the dogs capture and killing of the fox and how this is entertainment to the gentry, sensing in this her relationship to her potential hunters especially by virtue of her being of a lower class, Marnie panics and gallops away.

In the film, which has used red as a sometimes trigger, as Marnie looks upon the killing of the fox and the gaiety of the hunt around this, she focuses upon an individual in a red jacket and this also triggers her to take flight. In the film, of course we make a connection between the red fox and the Red Fox Tavern to where Mark tracks her after her theft of Rutland & Co. When she had arrived at the tavern, after stealing from Strutt, we even see images of fox hunting on the wall, and portraits of individuals dressed for the sport in red jackets. Marnie has, herelf, never before participated in a hunt, seems oblivious to all of this as anything but decoration, and isn't bothered by the idea of the hunt until she a participant and witnesses first hand its brutality.