Return to Table of Contents for films

An exploration of a 1963 anti-nuke film that effectively explores Cold War trauma in children of that era, drawing a comparison to The Seventh Seal, and, oddly enough, considering a similarity with Funeral Parade of Roses

Released in 1963, after the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, Ladybug, Ladybug is a gentle antiwar film that explores the pressures children face living with the threat of nuclear war, a subject that was largely ignored, whereas today there is more awareness on children and trauma such as with the emotional damage had through fear of school violence as well as highly inappropriate training to survive school shootings. In the 50s and 60s, Cold War America was bomb shelter crazy and children daily dealt with the fear the bomb could drop at any moment. Drills had them hiding under their desks, once a month, from the threat of a nuclear weapon, when they had also absorbed that one bomb would mean many bombs that would wipe out whole cities and what they currently counted as civilization. Kubrick's Dr. Strangelove had yet to be released, but the popular, poignant, devastating On the Beach of 1959 had Australia grimly waiting for the radiation to reach their shores that had already annihilated all other countries. Hope of surviving nuclear attack was offered by shelters that not many communities had, and personal shelters that not many families could afford. A possibility was that this nuclear apocalypse would happen when children were at school, separate from their families. Enter Ladybug, Ladybug, the title taken, of course, from the song, "Ladybug, Ladybug, fly way home, your house is on fire and your children are gone, all except one, and her name is Ann, and she hid under the baking pan."

In the case of a nuclear emergency in which children might be sent home from school, those children would be as clueless as poor. little Ann.

The film begins with focus on a watch, which may refer to the Doomsday Clock, begun in 1947, first appearing on the cover of "Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists". Soon, an elementary school's alarm goes off, one that specifically warns of imminent nuclear attack. The principal and teachers believe the alarm is likely an error, but when they learn the community high school has experienced the same, and are unable to contact authorities about the matter as their phone lines are busy, they must consider the threat could be real. Though reluctant, as per the training given in their emergency drills, they send the children home in groups that are each headed by a teacher. The film follows the children and teacher-guardian of one such group and how they deal with their anxiety not only as a group but individually as each child splinters off for home.

The gentle, quiet of the film fragments in small pieces as the children confront very real life problems that they would face in such a situation, while the slow pace maintained throughout the long walk home also mirrors real life, roughly replicating the time it would take for rural and even suburban children to make their way home from school, and the excruciating uncertainties they would psychologically and emotionally face during such a walk.

At one point the children attempt to lighten the mood by singing "Have You Ever Seen a Lassie" while they follow each other in line on a hill beside the road. The visual of this undeniably references the conclusion of Bergman's The Seventh Seal as death leads the victims of the plague away in a dance of death.

On top of caring for the children in her charge, who peel away one by one from the group, the teacher, who is a mother, has her own concerns, worrying about her own child who goes to another school.

The first child of the group to arrive home is in near hysterics as she tries to warn her parents, who are farmers, they may be under attack. Busy and confident that the alarm is a mistake else they'd have heard other news, the girl's short-tempered parents, unable to assuage and deal with her fears, are only irritated and threaten to thrash her. Alienated, she goes to her room and hides under her bed with a pet to wait for the bomb she has become certain is on its way. After all, why would she be sent home if it wasn't?

Another child, arriving home to find his parents are absent, must cope with trying to find cover not only for himself but a beloved grandmother who has dementia.

One girl's family has a bomb shelter in which several children take refuge, but with no adult around to attend to them they have no idea how to care for themselves. Now what? They realize that though they have the bomb shelter they don't have any idea what to do in it, how to manage it. How long must they stay in the shelter? Forever? They've been led to believe the shelter would offer security, but in it they must deal with their own profound and frightening problems, their refuge perhaps even complicating their situation more than those children whose families don't have shelters. They are scared to leave it, even for a moment, to find out what is going on, horrified as well at the idea of living their lives underground. Even more disturbing? What to do if another child shows up at the door. Do they risk their security by taking in yet another person? Will they possibly expose themselves to radiation if they do so? Do they have the supplies necessary to care for another?

In the meanwhile, the principal, and the teachers who have remained at the school, have learned that the alert was a false alarm, caused by a short-circuit. They hurry to call the children's homes and set out in their cars to hopefully reach those groups still walking home.

One boy and girl, aged twelve, discover they have a love of music in common during the walk, even falling a little in love or like with one another. The girl loves opera and sings, while the boy had performed in Gilbert and Sullivan's Mikado as a lead, though he admits he doesn't sing very well. They make uncertain plans to get together in the future, their unspoken fear that there may not be a tomorrow in which this can be realized making for a poignant moment. The boy is one of those children who takes refuge in the bomb shelter. When the girl, unable to find her mother, goes to the shelter, hoping also for refuge there, the child whose family owns the shelter refuses to let her in, believing she is protecting those already in the shelter.

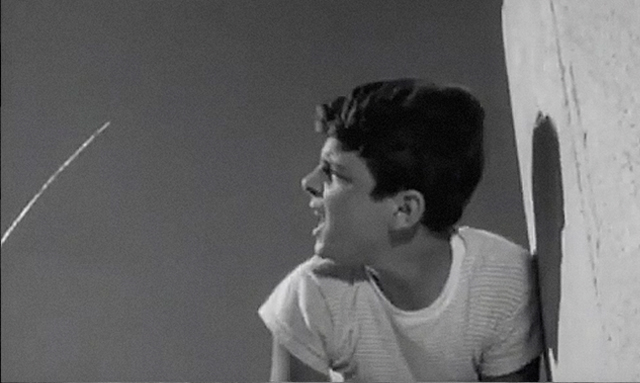

Though the Refrigerator Safety Act was passed in 1956, abandoned refrigerators were still deadly weapons for children who would play hide-and-seek in them only to find they couldn't get out. A child would fall unconscious in ten minutes and be suffocated in twenty-five. The movie's crisis occurs when the girl who was turned away from the home shelter, frantic in her search for shelter, hides in an abandoned refrigerator, sobbing as the lid shuts. Frightened for her safety, the boy who had fallen in love with her leaves the private shelter to find her, but passes by the refrigerator in which she had hidden. Immediately thereafter, he hears a plane, the vapor trail of which we see in the sky above him as he scrambles to scratch into the earth a hole in which to hide himself, which he realizes is impossible. Having been unable to find the girl, wholly exposed to the sky, he crumbles emotionally, screaming, "Stop!", as the sound of the plane magnifies and overwhelms, he believing that this is a nuclear strike. It's now we realize how essential the gentle, quiet of the film, and its slow pace, have been for the impact of this final sequence to which the action has been building. The weight of a dangerous sky bearing down on him, the boys terrified screams echo the psychic dread and nightmares of all the other children of his generation.

The quiet of the film also refers to, prior the great judgment, the breaking of the seventh seal in the Book of Revelations, which was followed by a silence in heaven for about half an hour, after which a censer filled with smoke was cast upon the earth, the angels also commanded to pour out their vials of wrath.

What surprised me is that for some reason I'd never heard of this film, though it is by Frank and Eleanor Perry who also did Dave and Lisa and The Swimmer, and The Swimmer is one of the great mid-twentieth-century films that defined the elite, suburban 60s. Where had it been kept hidden? There are many other cold war films that are well known, but these often enough are beloved largely for public service films and sci fi that have morphed into unintentional, unironic comedy. Ladybug, Ladybug does not fall into this category. It instead successfully puts the viewer in the place of every single child of that time, leading up to an unexpected conclusion that is horrifying not only for the certain death of the girl in the refrigerator, but the emotional trauma inflicted upon them all.

Though it seems unlikely, I have wondered if Toshio Matsumoto, who directed the 1969 film Funeral Parade of Roses, may have been somehow familiar with this film. I am going to explore this by way of (1) a tune that is used in both films and its meaning relating to nuclear threat (2) the importance of the anti-nuke performance in Funeral Parade of Roses (3) the meaning of the "rose" that is not simply a gay allusion but is related to the atom bomb and the anti-nuke performance (4) spaces in the film where other street performances take place that are intended to represent the sky and the threat of a nuclear device, and how they eventually become a poetic reinterpretation of the ending of Ladybug, Ladybug, and (5) how the Japanese word for ladybug fits in with all this.

One may not connect Funeral Parade of Roses with anti-war concerns, as the plot is an interpretation of "Oedipus Rex" that highlights the Japanese gay/transsexual/transvestite underground, Eddie as a transsexual male>female who murders her mother and inadvertently sleeps with her father, but tucked within is a subplot of anti-war protestors solemnly parading in the streets, a Zero Jigen performance that commemorates the Shinjuku Anti-War Day riots several months prior, a concern having been that America's military bases exposed the country to the threat of a Cold War military attack. Several times in the film "O du lieber Augustin" ("Oh, you dear Augustin") is played, a popular Viennese song reported to have been composed by the balladeer Marx Augustin in 1679, though written documents only date back to about 1800. The lyrics to the song remind of the horrors of the plague.

Every day was a feast,

Now we just have the plague!

Just a great corpse's feast,

That is the rest.

Augustin, Augustin,

Lie down in your grave!

O, you dear Augustin,

All is lost!

The lyrics are dismal yet the song was said to have become a symbol of hope, as Augustine, thrown into a mass grave of plague victims when he was drunk, survived and didn't himself become ill. When he woke, unable to climb out of the grave, he played his bagpipes and was rescued. Or so the story goes.

Sans lyrics, the tune accompanies Eddie as she and her friends go shopping, then another scene in which Eddie faces off with a rival in a mock western duel that becomes a physical free-for-all, the rival dressed in a traditional kimono while Eddie always wears western attire. The tune is used when a younger Eddie faces himself in a mirror and puts on makeup for the first time. The subtitle reads, "The day I was born, perish and disappear" which comes from Job's plaint over his tremendous suffering, such that he wishes he'd not been born. "Let the day perish in which I was born." As Eddie kisses his mirror image, his mother interrupts and beats him. We hear the tune in another scene when Eddie and two friends are confronted by a girl gang who accuse them of being fags, not real women, and they fight. Toward the end, we hear it as Eddie unwittingly makes love with her father just before discovering who he is, the film all the while flashing back to a party with frenetic shots of individuals facing the camera as they dance, the music slowed and sounding like a soundtrack to a horror movie, sometimes graduating into a lusher style, the conclusion being a sense of inescapable circularity that suits the predestination aspect of "Oedipus Rex", the future that is known already and from which one is unable to flee.

Matsumoto is obviously aware that the Book of Job, however personal the sufferings visited on its subject, that not only destroy his health and home but kill off his family, can be considered the proto-apocalypse of the Old Testament. Job--and certainly not his family--have done nothing to merit such suffering, just as Eddie, like Oedipus Rex, can be nothing other than what she was born to be.

"O du lieber Augustin" is the same song that has become "Have You Ever Seen a Lassie", and other variations thereon. That it originally had to do with plague and death is retained in the Ladybug, Ladybug film with the image of the dancing line of children recalling the line of those killed by the plague dancing as they follow death in The Seventh Seal.

it is not long after Eddie views the antiwar protest, in which a man lies down on the ground playing dead, that she looks up at the sky and near faints, seeming blinded by a sun which she has previously said was too bright for her, which reminds me of the end of Ladybug, Ladybug and its emphasis on the deadly sky crossed by a jet plane. After this, Eddie will find herself in what seems an underground world. She is returned to this world after her mock duel fight which ends with her being hit over the head, she losing consciousness in each case. The underworld is an exhibit of masks, mention is made of people always trying to escape, and we see a brief glimpse of a woman whose face appears to bear the scars of a nuclear explosion. At the time, this woman would have been among the survivors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Hibakusha (survivors of the bomb), who were discriminated against, feared for reasons such as being thought to be potentially contagious.

In Funeral Parade of Roses the "Augustin" song accompanies battles that represent the west against the east, the new against the old, what is fake and what is true. It is used when Eddie makes love with her father, before learning who he is, and the breakthrough images of dancers I interpret less as flashbacks then referring to the dance with death.

For me, as a Westerner, what is the link between Eddie's tribulations as a transsexual, and the antiwar protests, is clouded. But there is a scene that offers a provocative association, which I will approach in a bit. First, I want to explore the meaning of the rose.

The white rose, bara, in the Japanese language of flowers is said to represent innocence, silence, and devotion, in respect of gay culture is also the equivalent of "pansy" in English. Wikipedia states, in respect of the white rose used in gay Japanese culture, this is due the mythology that King Laius, Oedipus' father, would have sex with boys under rose trees, while a Japanese website speaks in general terms of the story, that in ancient Greece gay men confirmed their love under a rose tree, also acknowledging that the rose symbolized "blood, death, wounds, swords, perversions, and tragedies". No mention is made of Laius there. But, indeed, Laius came to be considered, by some, as "the originator of pederastic love" according to Wikipedia, meaning Greek relationships between men and "boys" who would be of an age to begin their military training, between the ages of fifteen and seventeen.This is based on the story of Laius, before he was even king, violating his friendship with Pelops, who had taken him in after his father's death, when he kidnapped and raped Pelops' son, Chrysippus, while tutoring him on driving a chariot. After this he became King of Thebes and the curse placed on Thebes a onsequence of this betrayal. The story of Chrysippus clarifies why Matsumoto's retelling of "Oedipus Rex" concerns gay/transsexual characters, but even the ancients argued over whether Laius had anything to do with the origin of male homosexual relationships at all.

XVIII. The Sacred Band, they say, was first formed by Gorgidas, of 300 picked men, whom the city drilled and lodged in the Kadmeia when on service, wherefore they were called the "city" regiment; for people then generally called the citadel the "city." Some say that this force was composed of intimate friends, and indeed there is current a saying of Pammenes, that Homer's Nestor is not a good general when he bids the Greeks assemble by their tribes and clans:

"That tribe to tribe, and clan to clan give aid,"

whereas he ought to have placed side by side men who loved each other, for men care little in time of danger for men of the same tribe or clan, whereas the bond of affection is one that cannot be broken, as men will stand fast in battle from the strength of their affection for others, and from feeling shame at showing themselves cowards before them. Nor is this to be wondered at, seeing that men stand more in awe of the objects of their love when they are absent than they do of others when present, as was the case with that man who begged and entreated one of the enemy to stab him in the breast as he lay wounded, "in order," said he, "that my friend may not see me lying dead with a wound in the back, and be ashamed of me." And Iolaus, the favourite of Herakles, is said to have taken part in his labours and to have accompanied him; and Aristotle says that even in his own time lovers would make their vows at the tomb of Iolaus.

It is probable, therefore, that the Sacred Band was so named, because Plato also speaks of a lover as a friend inspired from Heaven. Up to the battle of Chæronea it is said to have continued invincible, and when Philip stood after the battle viewing the slain, in that part of the field where the Three Hundred lay dead in their armour, heaped upon one another, having met the spears of his phalanx face to face, he wondered at the sight, and learning that it was the Band of Lovers, burst into tears, and said, "Perish those who suspect those men of doing or enduring anything base."

XIX. As to these intimacies between friends, it was not, as the poets say, the disaster of Laius which first introduced the custom into Thebes, but their lawgivers, wishing to soften and improve the natural violence and ferocity of their passions, used music largely in their education, both in sport and earnest, giving the flute especial honour, and by mixing the youth together in the palæstra, produced many glorious examples of mutual affection. Rightly too did they establish in their city that goddess who is said to be the daughter of Ares and Aphrodite, Harmonia; since, wherever warlike power is duly blended with eloquence and refinement, there all things tend to the formation of a harmonious and perfect commonwealth.

Now, as to the Sacred Band, Gorgidas originally placed them in the first rank, and so spread them all along the first line of battle, and did not by this means render their valour so conspicuous, nor did he use them in a mass for any attack, but their courage was weakened by so large an infusion of inferior soldiery; but Pelopidas, after the splendid display of their valour under his own eye at Tegyra, never separated or scattered them, but would stand the brunt of battle, using them as one body. For as horses driven in a chariot go faster than those going loose, not because they more easily cleave the air when galloping in a solid body, but because their rivalry and racing with one another kindles, their spirit, so he imagined that brave men, inciting each other to an emulation in adventure, would prove most useful and forward when acting in one body.

"Plutarch's Lives" Volume II

Dryden's commentary states:

The story which Plutarch had an eye to in this place, and which he relates himself in his comparisons between the Greek and Roman histories, is as follows. Laius was desperately in love with Chrysippus, the natural son of Pelops, with whom he maintained a criminal correspondence, till the young man was at last murdered in the night by Hippodamia, as he was lying by the side of Laius. Aeschylus and Euripides, who made this prince's life the subject of their tragedies, pretend that he was the first instance of this sort of love; and the Juno, to revenge the sanctity of the nuptial bed, sent the monster Sphinx to Thebes, who brought such miseries and devastations upon the Thebans. But it is not true, that Laius was the first infamous example of that kind. Plato, in his eighth book de Legibius, shews that there was a law in being before his time, forbidding a criminal commerce between men and men, and of women with one another.

Sex between adult males was taboo as to be a submissive male was demeaning as they were thus like women, though it was culturally appropriate between an adult male and a teen who was already viewed as submissive until reaching adulthood. And yet homosexual relations in the Sacred Band of Thebes was considered as promoting heroism. There must be some link between Laius, King of Thebes, and the Sacred Band of Thebes, and, actually, it wasn't Laius who was considered a being the first practitioner of male homosexuality, various sources instead gave it as a Theban practice, in as much as it was acceptable there.

Forgive me but I'm going to take a long paragraph looking at Chrysippus and the Oedipus myth before I get back to the rose and "Augustine" and the anti-nuke aspects of the film. Bear with me.

Some versions have Chrysippus killing himself out of shame, while there are others who have Chrysippus instead being murdered for purely political reasons. Chrysippus happened to be a bastard son of Pelops and it was feared that he would one day try to take possession of the throne, which explains his death. If we discard some of l the variables and reduce the story down to its most simple form, Laius stands out as one whose preference was not for women, he refused to sleep with his wife (allegedly because he feared an oracle that his son would kill him), she got him drunk, they had sex (this has a distinctly Dionysian cast to it), which leads to son Oedipus killing his father and marrying his mother. Laius' cultural duty to the marital bed and producing children has been violated and somehow leads to a violation of the incest taboo. We may begin to understand the violation of the incest taboo if we see this story as part of a cycle. Pelops' wife, Hippodamia, has been depicted as loved by her father, Oenomaus, and that was the reason he made the contest for her marriage a near impossible one, while another version has him arranging an impossible contest because of a premonition he would be killed by his son-in-law (shades of Oedipus). The contest was a chariot race against Oenomaus, and every suitor who lost it was killed. Pelops won due a deception by which Oenomaus was killed when a pin holding a chariot wheel failed, that pin having been replaced with a wax pin. Pelops killed the man who helped him in the deception and his line was cursed for this. He had two sons beside Chrysippus, Atreus and Thyestes, children of Hippodamia who are sometimes given as having murdered Chrysippus. Atreus' wife had an affair with Thyestes who became king, but when the sun moved backwards Atreus become king and banished Thyestes. When Atreus learned of the affair he pretended to welcome back Thyestes but instead killed Thyestes' two sons and served them to him. A delphic oracle told Thyestes vengeance would be his through a son fathered by him on his daughter, who would kill Atreus. The daughter was so horrified by the incest, she exposed the child, but he was rescued by a shepherd (just as Oedipus was exposed and rescued) who gave him to Atreus to raise. When he learned his true identity he killed his uncle, Atreus. Atreus had also two sons, Agamemnon and Menelaus who married the daughters of Leda. We end up having these two families, both of which have incestuous relations foretold by oracles, united through the person of Chrysippus. As far as I can tell, the parents of Oedipus, Laius and Jocasta, didn't have incest stories in their lineage. Instead, Laius' father was torn apart by during a Dionysian orgy, and Jocasta's grandfather, while dressed as a woman, was torn apart by his mother during a Dionysian orgy. Boetia was all about Dionysus. And then we have Chrysippus enter the scene and Oedipus happens with the connection of the House of Thebes with the House of Atreus of Mycennae via Laius and Chrysippus. Chrysippus somehow seems oddly connected to Oedipus, and as it turns out there is a myth concerning a woman, Chryisippe, who fell in love with her father, Hydaspes, slept with him without his realizing it, things started going bad for him and he realized what had happened and he crucified Chrysippe.

Back to the rose.

Plutarch, as we see above, claimed that the lovers who composed the sacred band made vows to one another at the shrine of Iolaus, a lover of Hercules.No mention of a rose garden is involved. Where and how does the rose enter into it?

What of the meaning of silence attached to the rose in the Japanese language of flowers? As the story of the rose in Japanese gay culture is attributed to the Greeks, perhaps it partly comes from the story of Aphrodite giving her son, Eros, the god of love, a rose, which he passed along to Harpocrates, believed to be the god of silence. This was said to ensure her indiscretions would be kept a secret.

In early Greek literature the rose and its symbolism was used in the same way for homosexual relationships as for heterosexual.

Some imagery in the film shows a rose inserted between male buttocks, which I'd initially assumed had simply to do with poetic rose symbolism, but in consideration of Laius as Oedipus's father, and mythically responsible for the curse of the sphinx, Matsumoto may not only be referring to homosexual love, considering that this is a retelling of Oedipus Rex. He may also be referencing the Sphinx, whose name was originally thought to remark on her method of killing, by strangulation, both sphinx and sphincter deriving from the same source, sphingein, a tight binding.

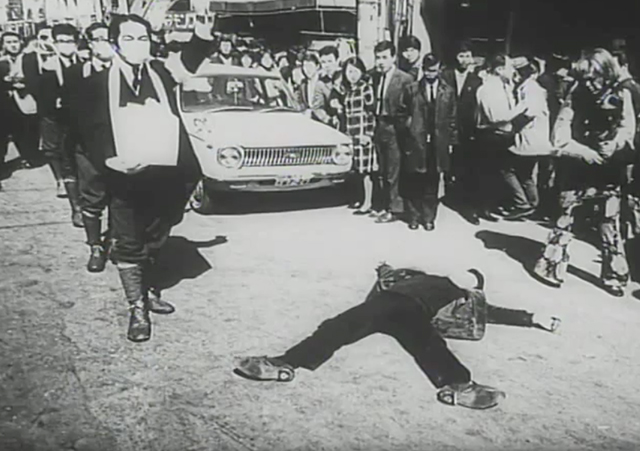

The movie makes a clear association of the rose with the street performance in which men carry, hanging about their necks, boxes intended to represent cremation boxes holding ashes of the dead. Some wear surgical-style masks over their faces, while others wear gas masks, the hoses of which are plugged into the urns, which means they are both breathing the ashes of the dead in and out, and I don't know whether the ashes in this instance are victims or if this is intended to convey the ashes belong to the individual themselves, that they are dying victims. During the middle of one such scene, the film cuts away to the title Funeral Parade of Roses.

Due this, I don't think the film could have been made without the anti-nuke protests. Though I've read that the title refers to Jean Genet's Funeral Rites, and though this may very well be the case on one level, this isn't a film concerned only with gay and transsexual subculture in Japan in the 1960s, nor is it only a retelling of the Oedipus Rex myth. The funeral procession of the anti-nuke street performance, boxes hung about necks in which the ashes of the dead are represented as being carried, is essential to the film, the title even associated with this performance that is concerned with the threat of Cold War nuclear attack, and thus also must be associated with the nuclear attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and their dead.

In another scene that takes place at night at the Marunouchi Station Square in Tokyo, there is a playful performance of tossing back and forth an inflatable chair, which I believe is a Quasar Khanh PVC Satellite Chair, which came out in 1968 and was not only mass-produced furniture but considered art. This will become significant, which is why I am going to the trouble of taking pains to make a clear identification of the chair, which I think is intended to represent a satellite nuclear device, or high altitude nuclear tests that were banned in 1967.

Watching the performance is an experimental filmmaker character who masks himself as Che Guevara. He eats a French baguette. Guevara would be here as he visited Hiroshima in 1959. The French baguette could address any variety of things--French involvement in Vietnam, Quasar Khanh being a Vietnamese who relocated to Paris as a teen and produced his work from there, the Aerospace furnishings having a showing at the the Paris Museum of Decorative Arts in 1969. After we are shown Che eating his bread as he watches the performance of the chair being tossed about, passer-bys are asked to hold out their hands, and their palms are stamped with what appear to be roses. One of the individuals asks, of the picture stamped on his palm, what it is, but no answer is given.

Why stamp anonymous individuals, who aren't gay, with the rose if it is only related to gay culture in the film, as many take it to be?

I don't believe it is a rose at all. I think the stamp instead represents the mushroom cloud from a nuclear explosion, the explosion conflated with the rose or disguised by it.

Just as in The Seventh Seal Bergman compared the devastation of past medieval plagues and future apocalypse to Cold War nuclear threat, as did Ladybug, Ladybug with the children dancing to the "Augustine" song clearly visually referencing Bergman, Funeral Parade of Roses draws parallels between the Theban plague, the "Augustine" plague, and apocalyptic literature, with the Cold War nuclear threat.

At the end of Ladybug, Ladybug, the boy having unwittingly passed by the refrigerator in which the girl has taken refuge, in a part of a rural field that is pockmarked with litter and other abandoned items, goes over to what seem to be two large concrete pipes sticking out of the ground.

It is beside one of them that he attempts to burrow into the ground as he looks up the jet trail left by the train, certain a bomb is about to be dropped.

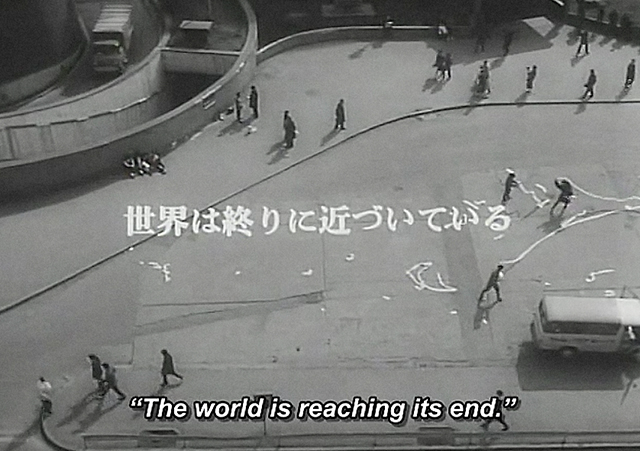

Toward the end of Funeral Parade of Roses, after Eddie and her friends have attended the funeral for Leda, her rival who has committed suicide, some of them gather again at the Marunouchi Station Square where performers had stamped the hands of passer-bys with the "rose" or mushroom cloud of a nuclear blast. The camera pans over the cityscape to show exactly where we are.

Beside a round building, some performers run about with white streamers. A subtitle states, "The end is nigh."

Going then to a medium shot of several of the friends, the filmmaker masquerading as Che Guevara says he is thinking about "the exit", while another quotes what seems to be a lyric from a song by Déodat de Séverac. "“Now, from the open ceiling roses are falling, one after another."

Many will likely take me to task for wondering if the performance with the streamers beside the round building, with the remark that "the end is nigh", a man then remarking on roses falling from the ceiling, is a poetic recreation of the end of Ladybug, Ladybug. But we already know that the space in which they are playing represents the sky as they were earlier playing with the Satellite Chair there, and the Satellite Chair belonged to a collection called actually Aerospace. The scene is certainly a reinterpretation/recreation of an earlier one in which Eddie nearly faints when she looks up at the sun. This occurs after she and a man on a bike, delivering noodles, nearly collide at an intersection, he falls off his bike, the noodle boxes open, and noodles are spread all over the ground.

Looking at the noodles, she flashes back to the anti-nuke performance in which one of the performers had collapsed in the street, playing dead.

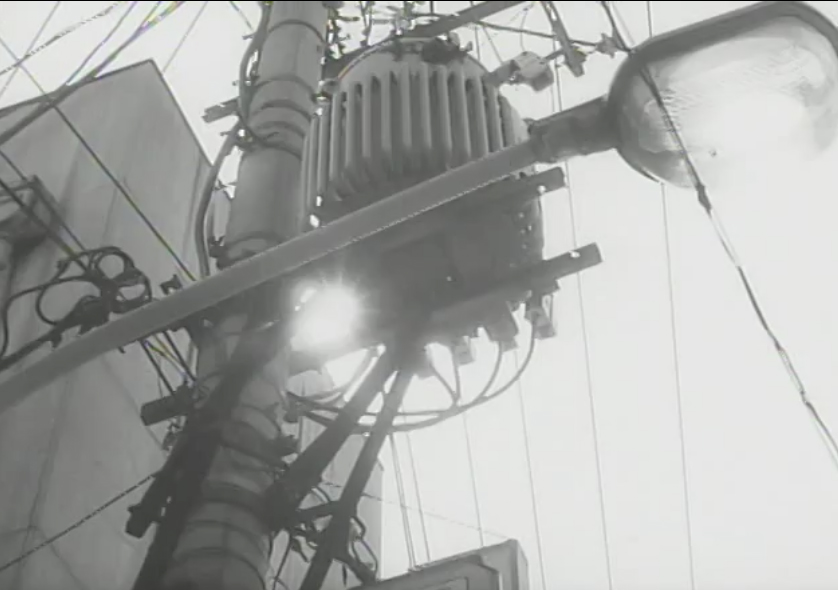

There are a couple other quick flashback images that will relate to the Oedipus Rex portion of the story, and she collapses after looking up at the sun in the sky. We should see the round transformer as being what will later become the round building beside the people running about with the streamers, and, I think, the round pipe beside which the boy tries to dig a hole in the ground to get away from the jet we see over his shoulder in the sky. Unable to hide, he will collapse against the side of the pipe, and certain the jet is about to drop a nuclear bomb, he screams at the sky, "No!"

I believe, in association with the anti-nuke theme, the blinding sun should be also interpreted as being the blinding flash of a nuclear explosion.

The word "ladybug" in Japanese tentou-mushi, or sun bug. It can also mean a path in the heavens.

Though it may be entirely coincidental that both Ladybug, Ladybug and Funeral Parade of Roses, which have anti-nuclear themes, use this song, as I'm not altogether certain there isn't a connection, I thought the use of the song in both films merited examination.

At the film's end, after Eddie has blinded herself, as she stumbles through the halls of the apartment building the film is completely silent, and remains silent to the end except for when a couple of discordant vestiges of the "Augustine" song bend the silence back, horrific, as she stands on the sidewalk with blood streaming from her eyes, the gathering crowd only staring on. The movie has throughout, broken the fourth wall, and as Eddie was blinding herself there was even a brief cutaway to a contact sheet of numerous photographs taken of her with bloody eyes. At this point, we need to consider Eddie as having moved from the position of one of the observers of the Funeral Parade of Roses street performance, to being herself the performer.

Approx 5400 words or 11 single-spaced pages. A 42 minute read at 130 wpm..

Return to the top of the page.