KUBRICK'S REFERENCES IN KILLER'S KISS

Go to TOC for this film ( (which has also a statement on purpose and manner of analysis and a disclaimer as to caveat emptor and my knowing anything authoritatively, which I do not, but I do try to not know earnestly, with some discretion, and considerable thought).

A Piece of the Puzzle

If you’re not familiar with Killer’s Kiss, here’s a bare minimum sketch of the plot up to about 3/4s of the way through the film. Davey, a boxer, falls in love with Gloria, a taxi-dancer at the Pleasure Land dance hall where customers purchase tickets for dances with dance hall hostesses. Gloria and Davey meet after Gloria’s gangster boss, Vincent, has raped her (this is intimated, not directly voiced), and Davey's loss of a big boxing match on the same night suggests his career is at an end. There’s nothing left for them in the city, so Davey convinces Gloria to run off with him to a new life in Washington state where his uncle and aunt live. When Gloria goes to the dance hall to get the pay owed her, the boss, Vincent, learns about Davey and resolves to get him out of the way. But Davey's manager is confused for Davey and is instead killed by Vincent's thugs.

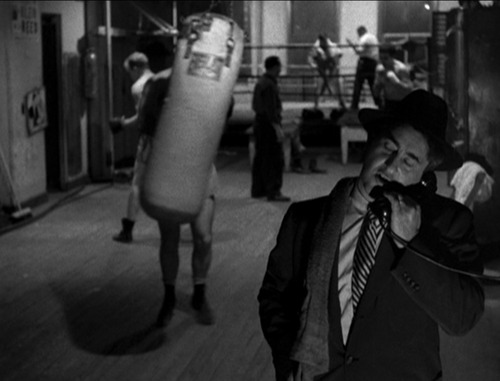

In Killer’s Kiss we have a couple of very curious shots concerning Davey’s boxing manager. The first is shot 19, of Albert making a phone call to Davey, informing Davey he can’t pick him up and he’s going to have to catch a taxi to the big fight (the Davey he will lose).

Shot 19

The effect had in the above shot, not so intense in the screengrab, is such that Albert seems to be standing in front of a rear screen projection of a gym rather than in the gym/set itself. When he hangs up the phone he turns to take a step toward the gym and a cut is made at a point where it looks like the rear screen projection begins.

Fast forward to shot 242, and again we have Albert in the gym, only this time he is in the body of the gym, standing to the side, and interacts physically with one of the boxers. The phone rings and Albert walks forward, toward us, the audience, to answer it, and once again suddenly we have the change in light so that we have again the same effect in shot 19, it appearing that he stands in front of a rear screen projection.

Shot 242 a

Shot 242 b

Kubrick cuts to shots 243 and 244 in Gloria’s apartment of Davey speaking with Albert, while Gloria listens, about getting his money for the failed fight. Shot 245 returns to Albert who hangs up the phone and walks out of this curious effect back into the gym. It is as though watching the barrier dissolve between him and the rear screen projection behind him and he being assimilated into it.

Why? Why have it appear earlier that Albert is standing in front of a rear screen projection and then in shots 242 and 245 do the reveal that shows instead the effect is a matter of lighting? Most people want rear screen projections to appear real. Right? And this seeming rear screen projection is fairly jarring as there are no other shots like it in the film and no real rear screen projections.

Why make a real set scene appear to be a rear screen projection, a man on a stage before a screen? Is it just a matter of bad lighting?

No, it's intentional.

In the phone call, Davey has arranged to meet Albert for the money in front of Gloria’s work place, the Pleasure Land dance hall. Albert agreed, saying, “I’m taking my wife to a show and I’ll just about make it.”

This arrangment is made as Gloria is going to the Pleasure Land to try to collect her money, and Davey is going to accompany her there. We are shown their arrival and that Davey waits for her in front while she goes in to get her money.

Albert is shown arriving in shot 277 but Davey isn’t there.

Shot 277

Cut to shot 278 and Albert moving to stand in front of the Pleasure Land entrance to wait for Davey. The street isn’t shown. Pleasure Land facade shots are always dissociated from the street, there’s never a pan from the facade to the sidewalk/street, but I’ve plotted everything out according to what we see of the street in the various sidewalk shots and according to shots that show the street we know that the Pleasure Land entrance is supposedly before the Victoria theater where The Man Between is playing, which is a film by Carol Reed about a man (James Mason), who rescues a woman who has been kidnapped and taken from West Germany to East Germany. The film is by Carol Reed, who also did The Third Man in which Orson Welles starred. The Man Between was released November 18, 1953.

Where is Davey? Davey had left just seconds before to chase down some Shriner drunks/clowns who grabbed and ran off with a scarf he was wearing. In the meanwhile, Gloria’s boss, thinking that Albert is Davey, sends down two thugs to either work him over or kill him, we’re not sure which was Vincent’s intent though he later insists he never meant for anyone to be killed.

The thugs confuse Albert with Davey, and in shots 287 and 288 we see the thugs corner Albert in an alley. He bangs on a door and on the windows of a building. We can hear the laughter of an audience inside the building, they watching either a staged show or a movie. Albert’s efforts to escape or be rescued are to no avail. The thugs kill him off screen.

It occurred to me that the rear screen projection effect and Albert’s saying he was going to a show fit in with his banging on the windows and our being able to hear an audience laughing, what is theatrical/cinematic becoming confused with real life. It's going to be difficult to describe how this is so, and I hope you'll stick with me. In his films, Kubrick plays a lot with expanding the role of the actor/character so they become as real entities conjured by their god of a writer and who are trapped in their predetermined world by that writer (or director). Wanting to keep this concise, I don’t have room to go into examples of how that’s so here, so I’ll leave it at that. Kubrick also plays with breaking down the barrier between the audience and the screen, most pointedly in A Clockwork Orange, he hacking down the fourth wall. For instance, when Alex is strapped into his chair in the theater during his programming, he is both actor and audience staring at the screen, the first movie he’s watching replicating his thug/droog life, during which we have his famous remark that blood always looks more real on screen. In the book, it's very clear that Alex is himself confused, unable to tell how the film he watches could not possibly be real life as the violence doesn't look staged. Later, he does in fact watch real life movies of Nazis. As Alex watches from his position in the audience, he looks at us, the audience, and we are not only the audience watching him in turn, we’ve also become the screen upon which the movie is being played, those flickering images of both the imitative film and the real life actions of the Nazis, the fictional Alex watching the very real horrors of the real world.

The intersections of reality, celluloid and theater are explored continually in A Clockwork Orange. When Alex and his droogs interrupt the rape of a woman on a casino stage, toward the film's beginning, the opposing gang leaps off the stage and engages in a fight with what is in effect their audience on the floor where the seating once was, theatrical masks looking on from the stage. When Alex assaults the writer, Alexander, and rapes his wife at HOME, the lighting design is as stage foot lights and the cinematic audience hidden in the dark window beyond them, a window which we face and so we are also removed from the audience and become as participants in the action. One could write pages upon pages on Kubrick’s work with content and its relationship to audience and the creator of the content, this being a strong component in all his films, but I’m trying to be concise here. I have approached this in some of my other analyses.

It’s one thing to theorize that Albert is as if trying to escape the film in shots 287 and 288, to find a way out of the fictional, cinematic alley into where that theatrical audience is laughing, or to at least try to get their aid, but those windows are closed to him. He's trapped. What about confirmation? Is it too much to hope for confirmation?

Another Piece of the Puzzle

In the last section of the film, Davey’s girlfriend, Gloria, has been kidnapped by her Pleasure Land boss and is held in a warehouse by two thugs. Davey forces the boss to take him to her. He disarms the thugs and has them stand against a wall along with the boss, Vincent. Gloria has been tied to a chair by the thugs. When Davey is unable to untie her, he calls over one of the thugs to do it. The two thugs, right in front of Davey’s unwitting eyes, wordlessly communicate with each other, via some cards, their intention to gang up on Davey.

Shot 368

I won’t go into explaining these cards right now (I do a few paragraphs down), but Kubrick shows these cards in close-up twice, in shots 368 and 373. He really wants you to pay attention to this Ace of Spades and the four of Spades beneath. Alert Kubrickians will perhaps notice that, as an ace is 11, we have here the number 11-4. So, Kubrick was using 114, for his own purposes, before Dr. Strangelove and its CRM 114 code, and even before the 1958 publication of the novel on which the film was based. It may be he was even attracted to Red Alert because of his use of 114.

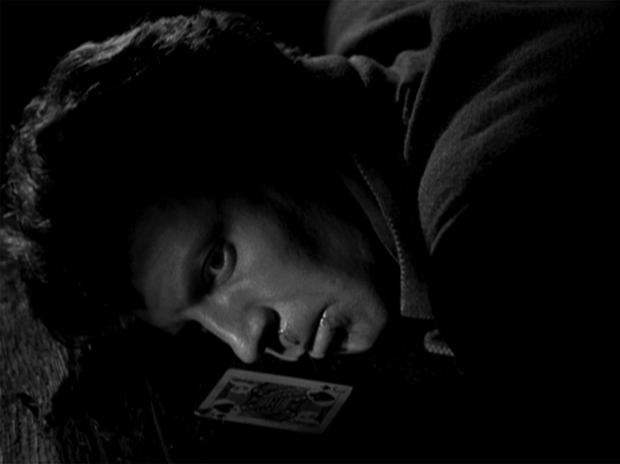

Finally, via the wordless communication of the cards and the go-ahead of a wink of the eye, the thugs attack Davey. And that attack involves these cards. The thug holding the cards throws the deck in Davey’s face, taking him by surprise, then while Davey is distracted by the cards the thugs jump him and knock him out–at least they believe they have knocked him out. In shots 390 and 393 we have a medium close up of Davey on the ground but his eyes are open and he is staring at a Jack of Spades that has landed right by his face. I’ll show screengrabs of these shots in a minute.

Trust me, these pieces are going to end up cohering.

More Puzzle

Kubrick may have used locations for accessibility and convenience, but Kubrick still chose to place the entrance to the Pleasure Land dance hall in front of the Victoria for a reason and it wasn’t because there was a facade there he wanted to use for the Pleasure Land as all the waiting on the sidewalk shots in front of the Pleasure Land dance hall either always face the street, never showing the facade, or only show the entrance to the Pleasure Land stairway but never in context of its environment or the street. He situates the dance hall geographically in connection to the Victoria and opposite a certain arrangement of marquee advertisements across Broadway but when he shows the supposed entrance to the Pleasure Land itself, the stairs that lead up to it, this location shot appears to be elsewhere and not in front of the Victoria. Though Kubrick employees pans in his shots, there is never a pan from the sidewalk/street that shows exactly where the action is taking place geographically, the camera never turns from the street to the supposed facade of the dance hall. The reason this doesn't happen is because two different locations are being used.

So why that particular spot before the Victoria?

Shot 277 a

Shot 277 b

I had already taken note of the Himberama ad observed in the shot but hadn’t yet explored it. See the ad? In shot 277 we don’t see the full Himberama ad, which has a top hat above with a rabbit jumping out of it. Here we only see Himberama and that it is a “4D production”. As Albert’s cab pulled up, we didn’t see the ad at all, but when Albert stepped out of it Kubrick made sure to have the camera rise to bring in the bottom portion of the ad.

What was I saying earlier about Kubrick entangling actors/characters and stage and audience? A kind of 3D experience.

But Himber! Himber professes to a show that engages the audience in a 4D experience.

So, I looked up Himberama. It was a show produced by the band/orchestra leader and magician Richard Himber.

From Fear and Desire on, there's something of the magic of The Tempest in Kubrick's films (a Shakespeare play referred to in Fear and Desire), the director a kind of magician, as was The Tempest's Prospero both a magician and a director, and actors and audience transported into an illusory world conjured by the director. So, when I see a hit of magical anything referred to directly, I pay attention.

What about Himber?

As I've already discussed, across the street from the Himberama ad, and this is probably by pure coincidence, The Man Between was playing, directed by Carol Reed who also directed Orson Welles in The Third Man. If you know anything about Orson Welles, you know he was a man of magic, and, as it would turn out, Orson Welles did, in 1945, a short movie for Richard Himber called Magic Trick which was to be used in Himber's Abracadabra, a musical comedy-magic production that Himber wanted Welles to coproduce. This didn't happen. Instead, Himber incorporated Magic Trick into Himberama which was supposed to have its initial viewing at New York's Town Hall but for some reason instead was given its premiere viewing at Carnegie Hall on November 13, 1953. This was followed by a brief run in December at Leow's 46th Street Theater in Brooklyn.

Orson Welles starred in this little film in which he, on screen, interacted with Richard Himber who was live, on stage, and they performed a magic trick together.

Another Orson Welles connection happens to be through Jamie smith, who played the boxer, Davey, in Killer's Kiss. Jamie had been, in Paris, a member of Orson Welles' theater troupe, appearing on the stage in Faust and Blessed are the Damned. He had also been in Welles’s film Othello. So here is Kubrick working with an actor who had studied under and performed with Orson Welles. Did Kubrick perhaps imagine this might bring Killer's Kiss to the attention of Orson Welles?

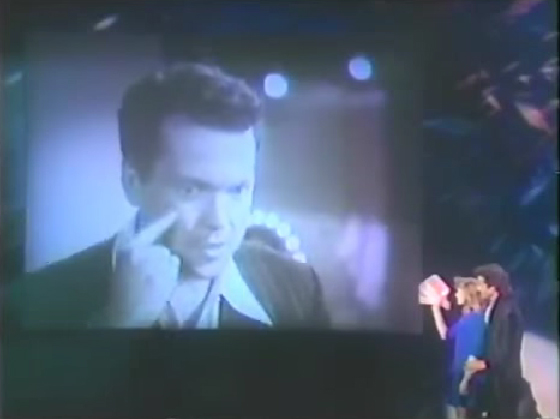

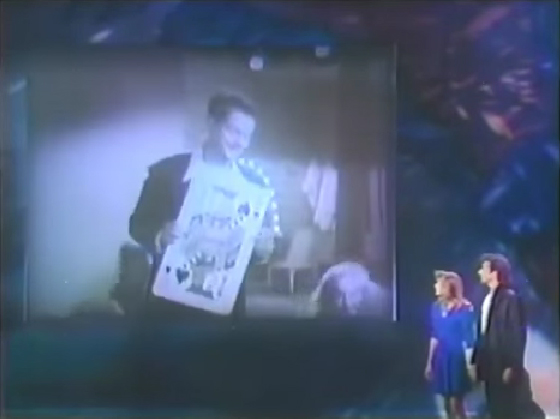

The footage Orson Welles made for Himberama lives on as David Copperfield used it in his 1992 special, "The Magic of David Copperfield XIV: Flying - Live the Dream", so, via David Copperfield, we can see how Himber and Orson Welles collaborated in their trick, Orson on the screen and Dave on stage, both interacting with the audience.

Below is the footage. You'll want to start at about 23 minutes.

Orson first sprinkles some magical applause powder that spills off the screen onto the stage, then tosses a pack of cards to Dave. On screen, Orson's cards are normal size, but tossing them to Dave they become oversize cards. Welles' instructs Dave to wrap the deck in a rubber band. Welles says he wants someone to "freely" choose a card, not be forced. He has Dave throw the pack over his shoulder into the audience where a man catches it and Orson instructs him to hand the deck to a woman as he needs a woman for the experiment. Orson asks the woman to hold the deck behind her and has her answer him if she's done so. Then the deck is extended to a man who takes from it a card. The man shows to the audience what the card is that he selected then inserts it back into the deck and Dave walks the woman onto the stage, she carrying the cards and shuffling them. Orson asks her if she's ever been hypnotized, utters some yabba-dabba words then asks her to throw the deck of cards at his right eye.

She throws them. Kind of almost exactly like how the cards were thrown at Davey's face?

Orson catches one of the cards (now normal size) and shows it as being the Ace of Clubs. No, Dave says that it was instead the Jack of Spades. Orson then raises a very overlarge card and says, "You know it's remarkable, but on the screen some objects enlarge quite unusually." He turns the card over to show the Jack of Spades.

The Jack of Spades is revesed on the screen. I read this is because Copperfield had it reversed so he could interact with it using his good side. Which means instead of having the cards thrown at Orson's right eye they were originally thrown at his left. Just as "Dave" was dubbed in every time Orson had said "Dick" (for Richard), then "right" would have been dubbed in for "left".

Though the Ace of spades and 4 of spades were the two cards that were several times shown the audience of Killer's Kiss, after the cards are thrown, when Davey is lying on the floor, subdued, the Jack of Spades rests beside his face. The Jack is a profile card, for which reason it is called One Eyed Jack, showing its right eye, and we have an oppositional profile with Davey, he showing his left eye.

Orson would have been showing his left eye with the proper, original orientation.

While the Jack of spades shows its right eye, the Jack of heart, another profile card, shows its left eye.

Orson has at least three times said the cards are “freely chosen” which would have been significant in Kubrick’s referring to this Wellesian magic trick as Kubrick’s films unfailingly deal with free will as versus predestination. With the magic trick there is the illusion of free will but the result is predetermined through its being fixed. What has happened is that some kind of card "force" has been employed so that the Jack of Spades, the preselected card, was chosen.

Albert’s seemingly standing before the rear screen projection (before a movie) is revealed by Kubrick to be purely a matter of illusion. But it is more than that, it is playing with the idea of audience interaction with the film, just as was had with Welles and Himber. The audience magically enters the pre-scripted story while the magician is able to transcend time and interact from the pre-scripted story with the live audience.

When Albert is before the seeming rear screen projection, speaking with Davey on the phone, we have, as it were, a replay of Himber (here David Copperfield) speaking first with Welles by the phone then moved to direct interaction with Welles on the film screen. Albert appears to be before a rear screen projection, but then is later shown as being part of the action in the rear screen projection, the two fields merging. When Albert is in the alley, pursued by the thugs, mistaken for Davey, he tries to get into the theater where he hears people laughing, he tries to get their attention, but he is unable to escape his cinematic situation into the audience.

The 11-4 formed of the Ace of Spades and the 4 of Spades, the silent message between the two thugs on attacking Davey, the cards to be tossed in his face, throwing him off balance, refers back to shot 114 in the film. Shot 114 is the shot during the boxing scene where we have the deciding punch that fells Davey and effectively ends the fight. He manages to get back up after a struggle, on the count of 8, but is done for. The fight has been decided. But not only does Davey take the punch, the audience does as well (in another interaction of audience and action) for the boxer aims directly at the camera and we have the audience’s POV as Davey’s, getting hit in the eye, falling, the camera jumping all over the place and focusing finally on a light above. When the one thug is showing the other the Ace of Spades and the 4 of Spades, which are 11-4, as a secret signal to gang up on Davey and knock him out, Kubrick is also signalling the audience and referring them back to shot 114. Though they never know it because they don’t know the fatal blow occurred in shot 114. They only know that those two cards are important and are a signal between the two thugs as to their plan.

Shot 114

The audience doesn’t know about the reference to Welles and Himber either. Maybe, in 1955, some might have caught it, who had seen Himber’s act, but that would have been a small percentage.

Certainly Orson would have observed the reference if he’d seen the film?

Here’s a quote from Orson on Kubrick that appeared in perhaps the April 1965 issue of Cahiers du Cinema?

Welles: Among those whom I would call ‘younger generation’ Kubrick appears to me to be a giant.

Interviewer: But, for example, “The Killing" was more or less a copy of "The Asphalt Jungle”?

Welles: Yes, but “The Killing” was better. The problem of imitation leaves me indifferent, above all if the imitator succeeds in surpassing the model … What I see in him is a talent not possessed by the great directors of the generation immediately preceding his … Perhaps this is because his temperament comes closer to mine.

Had Orson seen Killer’s Kiss and noted Kubrick’s inclusion of elements from the Himber film in it, and his reframing in terms of his own cinema magic, then the above quote may expand beyond discussion on The Killing to Killer’s Kiss.

Certainly, as I’ve stated above, all this was more than an homage to Welles. Kubrick’s reframing of the Welles/Himber film is a continuation of statements he was making in Fear and Desire, when he twice focuses on The Tempest in which seeming reality is but the magic of Prospero, and yet Prospero is unable to leave that island of enchantment unless given leave by the audience. Humbert, too, was trapped in that “enchanted” environ in which the number 242 appeared over and over again at crucial times (for Nabokov it was instead 342, he repeatedly pointing out its synchronicity, while Kubrick changed it to 242 and left it to the audience to notice the synchronicities). The Torrances were trapped in the enchantment of the Overlook. Eyes Wide Shut ended with Bill and Alice being unable to discern, of their journey, what was real and what was dream, except to say that no dream is just a dream and reality wasn’t the whole truth. However they were glad to be “awake”.

March 2016 transferred to individual post. Approx 4021 or 8 single-spaced pages. A 30 minute read at 130 wpm.

Go to Table of Contents of the analysis (with supplemental posts)

Link to the main TOC page for all the analyses