Carnival of Souls as a truly modern American horror story and retelling of the Orpheus myth with Eurydice acting as her own Orpheus-savior

The first time I saw Herk Harvey's 1961 Carnival of Souls, the version not yet restored, edited down for drive-in audiences, was perhaps in the late 1970s on a tiny black-and-white television that was about the size of a small microwave oven. The year is uncertain but the medium is not, nor that it was the hacked up version (I do know I saw it well before Poltergeist), and that the impact was such as the lead actress, Candace Hilligoss, recounts in her memoir, she and director, Herk Harvey, unaware that late night television showings of the stolen film had created a cult following so dedicated that individuals were calling stations hoping to learn when the film was next scheduled. What was uncanny about Carnival of Souls was while Poltergeist would depict the sometimes ghostly uncertainty of old analogue technologies, the seance that could be tubes and transistors capturing airy spirits, Carnival of Souls, though a feature film, had the aura of being that eerie transmission, as if it was a dream captured and printed on celluloid. Herk Harvey had told the writer, John Clifford, what he wanted was a Jean Cocteau feel with an Ingmar Bergman look. Cocteau's dreams are fantastic and beautiful if sometimes tragic, disjointed, defiant of the constraints of linear time, and Ingmar Bergman excels at the romantic, comedic mundane, death and identiy-dissolving nightmare. I'm well acquainted with the works of both directors, and while I have never thought of Cocteau or Bergman while watching Carnival of Souls, Herk was certainly influenced by them in his grand assertion that Middle America had its own troubled poetic soul worthy of the art house, which he would depict in a story that sidelined Orpheus in favor of Eurydice attempting to heroically secure her freedom from an untimely death. Her organ music, however, will begin to shift from the strain that persuaded Hades to conditionally release Eurydice to Orpheus, and instead becomes colored by an underworld that swirls to her dance macabre. Mary returned to the scene of the accident before she left Kansas, and perhaps she ought not have, perhaps then is when she began to recede into the shadows.

Carnival of Souls had the surreality of the cut-ups one experienced via radio while night driving as one twiddled the tuning knob on the vaguely-lit dashboard, seeking a clear message in the brackish night waters, and suddenly a station would beam into the car with radiant brilliance, persist for a time, then begin to splinter and blend with other channelings. Speaking from experience, if one's drive was long enough, such as if you were traveling from Lawrence, Kansas, through the dark of the prairie flatlands west into Colorado, the effect of the whole was eventually hallucinatory. Mary Henry's drive from Lawrence (never named) to Salt Lake City is well enough during the daylight hours, but at night, as she nears Saltair, her radio gives way to all one eerie musical transmission, no matter what channel she turns it to, the individual stations having lost all sensible individuality and becoming an ocean of sound, in Mary's case the organ.

Day time driving may be boring, depending on the route, but there is something always to see, whereas at night in the sparsely populated west the profound darkness creates a sense of being resident in the waiting room that is purgatory. There may be nothing upon which to fix one's eyes other than the auto's twin beams, and an occasional glance in the car's window at one's reflection which can seem spectral, bouyed on that seeming infinite nothingness of the dark beyond. After a while, anything that breaks the monotony can take on the sense of the otherworldly, even a distant farmhouse. But there may happen instead an interruption that is so anomalous as to become a destination, as happened with Herk Harvey's initial experience of Saltair II, and one's drive becomes a trip, in the parlance of the LSD-pranked 1960s sprinting out of the speed-and-alcohol saturated cross-country orgies of the 1950s Beats. What in the daytime would have been just another "roadside attraction" is transformed by night so as to be an intrusion from another world. For Herk Harvey, it was Saltair II, itself a ghost of the Moorish-styled resort of Saltair I on the shore of the erratic Great Salt Lake. It was decided that Mary Henry must come upon it at night, stirring an accompanying vision of a ghoul in her reflection on the window, what might be initially excused as a hypnagogic hallucination.

The Saltair II that Herk happened upon was no salvaged aircraft hangar as it is now. It was the Saltair Dance Palace, home of the largest dance floor in the world. The west is big, and in that great expanse, whatever might grab the attention of a tourist had to be bigger than big, construct of the mind of a carnival artist who understood the spiritual dimensions of the anomalous on the psyche. The closer to the impossible, the more extraordinary is the situation, which becomes an event, even if obviously manufactured, the greater the opportunity for the awe-inspiring paranormal intrusion of the Spirit World. And what is even more profound than a spectacle attended by thousands of tourists? One that has been left behind, a relic of a former civilization. For Herk, the then abandoned Saltair II, which had been home of the largest dance floor in the world, was so transfixing as to inspire, even require a film. Thus was born the character, Mary Henry, who could only be confounded by Saltair II if, like Herk Harvey, she lived distant enough from it that she was unaware of its existence before being brought to its location by--what?--maybe a job. John Clifford, the writer, says they were considering using the Reuter Organ facility for shooting and because of this he decided upon a character who was an organist who went to Salt Lake to work in a church, thus seeing Saltair.

Saltair I, 1893-1925, destroyed by fire

Saltair I, 1893-1925, destroyed by fire

A 1927 ad describing Saltair II but showing Saltair I

A 1927 ad describing Saltair II but showing Saltair I

Saltair II, 1926 - 1970, destroyed by fire

Saltair II, 1926 - 1970, destroyed by fire

Mary's first glimpse of the abandoned Saltair II in "Carnival of Souls"

Mary's first glimpse of the abandoned Saltair II in "Carnival of Souls"

Mary visits Saltair II with the priest in "Carnival of Souls"

Mary visits Saltair II with the priest in "Carnival of Souls"

Though Herk stated he had intended to capture the gothic with certain elements, such as the organ that haunts Carnival of Souls, and that he was influenced by Cocteau and Bergman, in some ways Carnival of Souls feels like it may be the first truly American horror film, divorced from New England and Edgar Allen Poe, from the vampire fangs of European castles, ships burdened with plague rats, and the fairy legends of Irish bogs. Most everyone would likely argue me out of this--even I could argue against this view with very little effort--and yet aesthetically Carnival of Souls seems a dramatic shift away from the usual stranglehold of upper class posturings as well the superstitious imaginations stereotypically associated with the unschooled lower class. True, Poe is considered the pioneer of the psychological horror story, but his brand of observation is bound up in attitudes dependent on the investment of hierarchies and proprieties by birth and social legacies. In so much horror, we feel New England and English and Irish forebears in every step and breath, as well the colonial argument against a sense of inferiority to the UK and continental monarchies even while the architecture of 18th and 19th century horror honors the elite, however often damning it, sometimes jealous of wealth and rock solid titles, other times chastising, but inevitably co-dependent or captivated, a brand of fiction that prevails and is absent of real examination of its obsessions and relationships.

The haunts of the Carnival of Souls of Kansas and Utah, of the Great American Desert, are instead those of Euro-Americans so cut loose from their cross-Atlantic provenance they are utterly divorced from ancestral origins and the typical Christian terms of salvation and damnation, heaven and hell, which will seem odd for me to say as I'm going to be discussing below the film in respect of the featured stained glass windows in the church where Mary has her new job. It's not just half a continent that distances the territory across the Missouri River from the east, but a loss of meaning of former potentates and their claims on cultural etymological rights. The children of the colonialists have become ethnic Americans, if not indigenous, and what has been wrought of the so-called melting pot is in flux, destabilized and reorienting itself on what is still frontier, the animal that is their adoptive birth continent ever resistant to control in a way not advertised or anticipated by all who trusted the religion of "improvements" to the land and industry. What is left is elemental and existential. Mary Henry drowns in the waters of the Kansas River, but the Great Salt Lake can defeat her denial of death because water identifies with water and the Great Salt Lake is the American Dead Sea (a misnomer ignoring the life the hyper-saline water does house and support). Following Hiroshima and Nagasaki, while its sci-fi sibling negotiated the atomic age, divided by pessimism and optimism, a new brand of American horror took a turn down a surreal path that dismantled the veneer of civilization to expose its patent constructed absurdity. Nothing was as touted. Cognitive dissonance, even if denied, was standard. Everything was composed of layers of varying perspectives that were to be stripped away, ultimately revealing the only certainty was a guardian trickster. Confidence in the presumed real could crash in an instant leaving one in an alien universe. Mary Henry shops for a dress in a department store, and while in the vulnerable environment of the dressing room the world changes so that she is neither seen nor heard until she enters the environment of a park where there is birdsong. This breaking of the spell of silence only works once, the second time home base trickster-shifting so an identical grounding turns out to be false. The odyssey of David Lynch's Dale Cooper would have him, on the brink of winning, Laura Palmer saved from death, her body having disappeared from the river shore on which she'd washed up, he returning her home, forget the telltale signs that call for circumspection so his impossible long drive from Texas to Idaho, made all in one day and night, ends with his plaintive question, "What year is this?", and the lights of the world in which he was certain shut down. But I'm getting way ahead of Candace Hilligoss' Mary Henry who disappears on the shore of the Great Salt Lake, then is retrieved from the Kansas River out of which she'd stumbled several days earlier, the only survivor of a car that had crashed through a bridge's railing into the river. The situation isn't to be compared with Ambrose Bierce's An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge in which a condemned Civil War prisoner escapes his hanging on a bridge when the rope around his neck breaks and he falls into the river, free, for that's horror of a different ilk, the soldier in his last few moments having only imagined escaping and reuniting with his wife. There's a significant difference between the soldier's anesthetizing hallucination of a second chance at life and the situation of Mary Henry. Bierce's story elicited horror but was a tragedy. Individuals were intended to examine their own beliefs on the value of life and accept more humanitarian measures than execution. Mary Henry's story, breaking physical laws, translates her into the realm of myth and allegory, always uneasy territory with no clear answers. We can try to approach her as a purely human heroine, and the movie does attempt to do this, but she must ultimately remain mysterious.

Again, user discretion is advised on my remarks per the history of American horror above. Still, the fact remains that Carnival of Souls was a game changer, an influence on such people as David Lynch and George Romero because it was decidedly different, and part of this difference had also to do with civil rights, for which reason we find Carnival of Souls impacting the making of Romero's Night of the Living Dead. There's a very intimate appeal to Carnival of Souls and Mary Henry that communicates on a fundamental level the American equal rights movements and sensibilities of the era and artists recombining and reflecting on social spaces in their art. Surrealism was born out of WWI in Europe, a history I won't get into here, and it impacted American art on an ideological and political level. American surrealism (and I do look upon Carnival of Souls as owing a good deal to surrealism) was not going to be the same thing as French, as the English, as the Swedish. It had its own flavor. Part of that flavor was surrealist-horror giving opportunity to portray uniquely American landscapes and dissect American mindscapes and systems.

SOME NOTES BEFORE CONTINUING

Harvey...cites two filmmakers in particular as his guiding light for Carnival, "Bergman for the look of the film, and Cocteau--I think he did more mind-expanding existentialism."

The Peninsula Times Tribune, 15 Nov 1989

Outside Salt Lake City, he came upon a decaying pavilion called Saltair. "It's the weirdest place, I think I've ever seen. It's constructed about a mile and a quarter out into the Salt Lake, and at that time Salt Lake had receded, so here it was, just on this white salt, and it was dusk and the sun was setting, and I saw this background with the Arabic towers. It was almost like: Is this really here? Am I seeing what I think? So I stopped the car and walked down there, and it was spooky." When he got home, he told a Centron colleague, John Clifford, about the vision. They sketched the outlines of a story, and three weeks later Clifford had a script built around Lawrence and Salt Lake locations. (One of the most striking--the Reuter Organ Factory in Lawrence--was the motive for making the central character an organist.)

...

Mary Henry's alienation is part of what's given Carnival of Souls its lasting interest; the movie reads like an existentialist text. "At the time," Harvey observes, audiences "never really made that connection--of her being a loner outside society. Today they make that connection very strongly, especially the younger people..." If this doesn't sound like typical horror, consider the influences. Harvey cites Bergman ("the look of Bergman") and Cocteau's "'Blood of a Poet' and 'Beauty and the Beast'--the mood of those things!" A Cocteau picture is "not a film where you say, 'I'm scared', but you come out and the mood stays with you. It's sort of a strange, ethereal mood. And that's what I really tried to do...We intended for that film to go in a fine arts theater. Instead, it went into drive-ins!" he laments. And that was a disaster.

The San Francisco Examiner, 16 Nov 1989

Almost 30 years after they wrote and directed it, the makers of what became one of the most celebrated art films of 1989 still enjoy arguing about it.

"I distinctly told you I wanted a [Jean] Cocteau feel with a [Ingmar] Bergman look," Harold "Herk" Harvey, 65, a retired industrial filmmaker says.

"See," says John Clifford, 71, a retired industrial film screenwriter, "that's more arty than I am."

The Kansas City Star, 29 Jan 1990

HARVEY: OK, I played the part of the man in the film. What am I?

CLIFFORD: I don't know, I refuse to answer these things as I writer. I mean, what did you think you were?

HARVEY: I thought that I was the one who was questioning her ability to come back. I said this is against the laws of nature, or this is against religion...

CLIFFORD: Is that why you peeked in her bedroom window?

HARVEY: I don't know why I did that. Well, that's because the writer said to. No, I agree with that, I don't know for sure, except I do know that I felt, in playing the part even, that he was a laid back malevolent character in the sense that you never see him except maybe in the dance and a couple of looks actually be aggressive to her. Like many of the horror shows today have a lot of actual physical horror in it.

...

CLIFFORD: Sometimes I think we shouldn't explain anything...

HARVEY: That's probably true. Because sometimes it's like a husband and wife who know too much, enchantment tends to disappear.

SOURCE: Carnival of Souls selected-scene commentary featuring a 1989 interview with Herk Harvey and John Clifford

EXAMINING CARNIVAL OF SOULS IN RESPECT OF ITS WINDOWS, REFLECTIONS, MIRRORS AND RADIOS, AND HOW THEIR USE IS INFLUENCED BY AND DIFFER FROM COCTEAU'S ORPHEUS

In Carnival of Souls, Mary Henry (played by Candace Hilligoss) survives a drag race in which the car she's in plunges off a bridge into the Kansas River, two friends who are with her perishing in the waters. She emerges from the river after three hours, which we know is impossible, but she seems unscathed with the exception of having no memory of what happened in the water. After she returns to visit the scene of the accident, the bridge since repaired, the auto holding her friends still being searched for, we next see her practicing on an organ at the Reuter Organ Company in Lawrence, KS. While the organ company isn't named, I will refer to her as being from Lawrence as it is convenient (and I was born there). Her playing attracts workers to gather and appreciatively listen, including the men who work in an area papered with girlie pin-ups from a calendar. We learn she has a job as a church organist awaiting her in Salt Lake City, to which she'll go ahead and travel despite the very recent trauma.

The stained glass windows at the church play such a prominent role in the film I thought I'd try to locate them, unaware at that point how Harvey had been influenced by Cocteau, who poetically used mirrors as doors to the underworld in his Orpheus. On the Reuter Organ Company website, there's a listing for their organs, and one of them is in Lawrence at the Trinity Episcopal Church, an instrument of 1354 pipes made for it in 1955. I had thought it likely the church where they filmed would have a Reuter organ and be in Lawrence rather than in Salt Lake City, and I quickly located an image on the Reuter website that showed this was the church in the film and that one of their organs was located there. What about the stained glass windows? Might I find images of them? Fortunately, the church's website has a PDF detailing the history of its stained glass art, and the windows were the ones in the film. All were made by J. Wippell & Co., Ltd. and placed in the church in 1956 with an extensive restoration after having been gutted by fire in 1955.

I've since found that, The Movie That Wouldn't Die!, a 1989 documentary on Carnival of Souls, relates the name of the church. It would have saved me some trouble if I'd been aware of it and watched it first.

The stained glass windows should be considered relative to how Mary first experiences her visions of the ghoul who begins haunting her with her arrival in Salt Lake City, as she passes the abandoned Saltair II pavilion. The "weird" has entered with the radio, no matter the station, playing only eerie organ music. We see her reflection in the window of the passenger's side of the car. Then we see the ghoul seeming outside the window but within her reflection.

Mary's reflection in the car window

Mary's reflection in the car window

The ghoul appears in Mary's reflection

The ghoul appears in Mary's reflection

As Harvey had said he wanted a Cocteau feel, and the story is essentially a reworking of the Eurydice myth, I'm going to assume that Harvey paid attention to how Cocteau used mirrors in his Orpheus as gateways to the underworld and that Harvey's use of windows was considered and methodical. For Cocteau's Orpheus, death was not horrifying, he was in love with it, as represented by the magnificent Maria Cesares, and it was in love with him though this was not permitted. It was from the underworld, after all, that Orpheus received his newest poetry from another poet who had been killed. Moving between the world of the living and the dead, Cocteau sometimes has mirrors very simply act as doors, while with Orpheus gloves are used, so that he seems to enter into a reflective surface that behaves like mercury. Instead, the effect was achieved with water, and we should perhaps perhaps relate this with Saltair and the Great Salt Lake being such a powerful attraction to Mary. As I noted above, The Great Salt Lake is also known as America's Dead Sea.

Whereas in Cocteau's Orpheus play, messages from the underworld, which Orpheus accepted as his own poetry, were transmitted by a horse, in the film these poems were received via a car radio, not dissimilar to Mary hearing the organ music on her radio as she nears Saltair, which is the only time in the film the underworld's music is delivered in this fashion. Mary visits the scene of the accident before leaving Kansas, and when she returns to her car and turns it on, Harvey immediately cuts to Mary playing and tuning an organ by means of a nazard stop. This seems a way of linking the car and its radio to the physical organs Mary plays.

Mary returns to her car at the scene of the accident and starts it...

Mary returns to her car at the scene of the accident and starts it...

...abrupt cut to Mary tuning an organ via the knob of a stop

...abrupt cut to Mary tuning an organ via the knob of a stop

Mary attempts to tune the car radio but it's all organ music from the underworld

Mary attempts to tune the car radio but it's all organ music from the underworld

Orpheus receives his poetry by automobile radio transmissions from the underworld

Orpheus receives his poetry by automobile radio transmissions from the underworld

In Utah, progressing from Saltair to the rooming house where she'll be living, as she settles in Mary believes she sees the ghoul outside the second floor window of her rental, this time no glass intervening as the lower pane is open. She goes to look out the upper pane of the window and sees nothing, only her doubled reflection in the two panes of glass formed by the lower pane raised behind the upper. Mary will complain not that she is seeing a ghost but that she is being stalked by a man, however the viewer already knows what she's seeing is a phantasm. Mary should know this as well, for these visions have occurred in impossible locations, but she's unable to comprehend them as anything but physical.

The movie also seems, at times, to tie the ghostly image with her personally, psychically, as with the move to the doubled reflection, an alternate reading being hinted at that the ghoul is not only a phantasm but relevant to her never having desired a romantic relationship, as if it represents some past trauma, but the movie never fully explores this.

Screengrab from Carnival of Souls

Screengrab from Carnival of Souls

Screengrab from Carnival of Souls

Screengrab from Carnival of Souls

The next day, Mary goes to the church where she has the new job as organist and meets the priest. As she practices, he smilingly enthuses to another how the church now has an organist who is able to speak to the soul. The priest likely assumes that they have hired an organist who approaches their work as also a spiritual mission, not just a talented professional. But before Mary had left Lawrence, during the scene in which she was practicing organ at the Reuter Organ Company, when discussing her new position she made it clear that she viewed it only as a job. The response was encouragement that she bring more of her soul to it and her music. The fact is, it's probably healthier, boundary wise, with musicians playing in churches, for it to be just a job, and many musicians will commiserate with her approach. We also have here a young woman who has spent her life developing a very specific skill for which there are limited career options, women's choices already limited in mid 20th century America. As a professional musician, a woman might often have had not much more opportunity to profit from her skills than taking pupils at home. Mary's rejecting the 1950s/1960s view on the devotion to the sacred being essential in church work is one thing, but she isn't loathe to voice her opinion, which signals her independent attitude and progressiveness. The movie complicates issues as it dances between Mary having a right to her independence, and that independence being also associated with ghostly dissociation from men and her fellow human beings. My assumption was that the fictional character of Mary has always likely been this way, and this is supported by a deleted scene from the film in which two men at the Reuter's organ company confer on how she's always kept to herself but acknowledge that even with this being her way she is behaving strangely.

The movie, often enough, seems to side with Mary's independent mindset, also illustrating her vulnerabilities as a woman who is considered not equal to men and has also to deal with sexual harassment. After all, it opens with Mary among three women in a car who are challenged to a drag race by two men, and Mary's friend being determined to show what a woman can do, but when they reach the bridge the men attempt to intimidate them, crowding them, bumping their car, and the women go off the bridge. This is fairly unusual, to have women competing with men in a drag race, and it seems there's a feminist aspect to the story. The women pay for almost winning the race by being forced off the bridge. While the river is fruitlessly searched for their auto, the men lie and plead the accident wasn't their fault, that they were the first on the bridge and that the women had been attempting to pass them. Then Mary comes crawling up out of the water. She could serve as a witness to what had happened but is unable to as she remembers nothing. Crediting herself with being a survivor, she struggles to continue on with her life.

To fully comprehend Mary Henry's refusal to remain dead, we need to look at Herk Harvey's history in theater and that in 1949, at the University of Kansas, he'd staged an experimental production of Irwin Shaw's Bury the Dead. Wikipedia describes it as an expressionist anti-war drama in which six dead soldiers refuse to be buried.

Each rises from a mass nameless grave to express his anguish, the futility of war, and his refusal to become part of the "glorious past". First the Captain and the Generals tell them it is their duty to be buried, but they refuse. Even a Priest and a Rabbi try to convince them to no avail. Newspapers refuse to print the story in fear it will hurt the war effort. Finally they bring in the women who have survived them, wives, sister and even mother. None succeed in the end.

Source: Wikipedia

I'm not familiar with the play but have glanced at it. The soldiers, unlike Mary, are well aware they are dead. They just refuse to be buried and ask the living to speak with them, to recognize them, to listen to them. They want to hear the sound of men talking and ask the living to not be afraid of them as they're not so different, just dead. They desire to be spoken to as equals.

While John Clifford is given full credit with writing the script, he claimed in interviews that he was allergic to arthouse cinema (my paraphrasing). We've only a few reminiscences on the creation process, how the story was conceived, but the movie was decidedly indebted to what were influences for Herk.

As Mary practices on the organ at the church, we are shown one of the stained glass windows, but with no description. In the church PDF on it we see it's titled "To have power" and that the scene is of "Christ ministering to the blind."

First view of a stained glass window in the church

First view of a stained glass window in the church

while Mary plays organ, an image of the blind

Image from "The Stained Glass Windows of Trinity Episcopal Church, Lawrence, Kansas"

Image from "The Stained Glass Windows of Trinity Episcopal Church, Lawrence, Kansas"

of the window showing the blind

We are then shown a man entering the church and standing under the balcony area where she plays. From a distance he looks like he could be the priest, but instead it's the ghoul. Cut to outside where the priest, overseeing some yard work, realizes that the organ playing has stopped. He goes inside to find Mary standing looking at another stained glass window. He asks her, "What do you see?" Mary, smiling, replies that she sees nothing. This comments on the biblical text pictured in the windows, specifically the healing of the blind which is depicted with two men and a child whose eyes are blank.

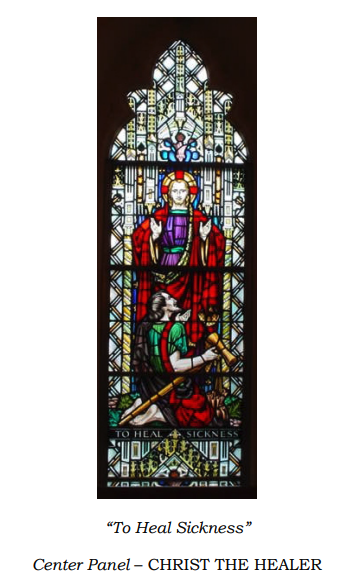

When the priest approaches her she is standing before the central window of the three in the balcony. It shows a man with a crutch and is titled, "To Heal Sickness".

Mary examines the stained glass window titled "To Heal Sickness"

Mary examines the stained glass window titled "To Heal Sickness"

Image from "The Stained Glass Windows of Trinity Episcopal Church, Lawrence, Kansas"

Image from "The Stained Glass Windows of Trinity Episcopal Church, Lawrence, Kansas"

of the "To Heal Sickness" window

She has, having practiced all day, gotten into a mood, so the priest suggests she accompany him on an errand across the lake. As he promises to show her Saltair, she agrees to accompany him.

At Saltair, the priest declines to go past a fence to explore it more closely. As he says, it wouldn't be appropriate for him, as a priest, to go against the law. Mary says then she'll return later and pursue it by herself, an independence that obviously disturbs the priest.

The blind window has a curious real world correlation. After visiting Saltair with the priest, when Mary returns home she takes a bath, which is interrupted by a knock on the door. Assuming it's the woman who runs the boarding house, Mary casually wraps her torso in a towel and goes to answer. Instead it's a man who lives across the hall, John Linden. A creeper, he tries to shoulder his way in though Mary keeps asking him to step back behind the door, in the polite and non-aggressive manner that women can be trained to have. He does stand back in the outer hall, as requested, and Mary goes to put on a robe, but he voyeuristically peers through the hinge-side crack of the door to watch as she changes.

Mary changes from a towel into a robe

Mary changes from a towel into a robe

Mary's boarding house neighbor voyeuristically spies

Mary's boarding house neighbor voyeuristically spies

through the crack in the door as she changes

Herk Harvey relates in an interview before 1996 (the year of his death) that he later learned from Sidney Berger, who played John Linden, that it was his glass eye with which he was peering through the crack at Mary. An interview with Berger instead clarifies that he was blind in that eye. So we have a person who is blind in one eye who appears to have sight, following our having been shown the church's stained glass window of the blind seeking healing. One questions if it was really such a coincidence as purported or has the story been somewhat twisted over time. From the point of view of this being coincidental, it becomes only a humorous tale. What is not being stated is how it relates to the window of the blind, which it certainly does. The window becomes John's double.

I've read enough interviews, and listened to a couple, to have clocked how stories about the movie change from person to person, they're not set in stone. This is to be expected. For instance, the filming at the department store has been related as being arranged with the manager that day, they did have permission, the use of a store employee as an actor was agreed upon, and the manager was also included to sweeten the deal. Another story instead gives the filmmakers as walking in, not seeking permission, and with $25 simply bribing a floor employee to look the other way while they quickly filmed and got out. I'm not sure what we can look upon as bible. People remember things differently, a person may recollect something differently over time, and many years had transpired between when the film was shot and when interviews were granted. In a collaborative, creative project such as this, a conflict in memories is almost guaranteed.

Immediately after John leaves Mary's room, she having refused going out to dinner with him, Mary seems to rethink this decision and steps into the hall to look for him. Instead she sees the ghoul looking up at her from the first floor. As the ghoul begins to climb the stairs, she rushes to hide in her room. But the person who next appears at her door isn't the ghoul but the owner of the boarding house, and she has seen no one else out in the hall. This is the first of several times Mary believes she sees the ghoul but they prove to be someone else. By the way, the rooming house owner is delightfully played by the San Francisco actress, Frances Feist.

The next day Mary goes to a department store, shopping for black dresses to wear at her church job, black being a standard color for a classical musician to wear in concert, though I'm sure we could also make an association with the funerary. It's a wonderful and mundane scene, just as was one in which she stopped at a gas station to refuel and get directions to the rooming house. Cocteau's Orpheus is an elegant reinterpretation of the Orpheus and Eurydice myth that communicates its deep history as part of the cultural bedrock from which Cocteau devines his poetry. With Harvey, the American landscape that backdrops Mary Henry's life has a different relationship to the myth, he instead approaching her environment and concerns with a very direct simplicity. It may seem absurd to compare the two films in this way, stylistically, but Harvey's guides were Cocteau and Bergman. Has Herk's style been influenced by his working in educational and commercial film? Is this directness a matter of the guerilla manner of filmmaking sometimes employed? Perhaps, but I'm going to assume this is also--what is not entirely due economics--an intentional aesthetic. Herk involves us with the main character who is very charismatic in her role, she sustains viewer interest throughout, but we have a natural alienation with her environments even while we are immersed in them, such as with the department store. We can feel we are physically present, whereas with Cocteau we are watching and absorbing Orpheus' remarkable odyssey as privileged but removed witnesses. However, though we are always a threshold removed from Orpheus' journey, Cocteau involves us in it spiritually. Despite the fact we might feel inserted into Mary's landscapes, within their threshold, able to breathe their air and feel their light, we are cut off from comprehending them--and I don't mean understanding Mary and what happens to her, but the absurdity of the normal. Cocteau seeks for us to be touched by the magic of the insensible eternal, to be at home with it. Mary's American drama is the trauma of the outsider who has no home because there is no real grounding within what purports normalcy, the ordinary and everyday.

The scene in which Mary had changed into her robe was a fragile boundary situation, as is when she retires to the dressing room in the department store to change clothes. John had voyeuristically trained his blind eye on her through the crack in the door. Now she becomes invisible to others, and is unable to hear the sounds of the world, only her own footsteps and voice.

Mary changes in the dressing room at the store

Mary changes in the dressing room at the store

Curiously, what should be in the dressing room, which we aren't shown? A mirror in which Mary would examine the fit of her dress. We may assume it is there but not shown.

She becomes connected with the world again in a park, when she touches a tree, looks up into its leaves at the sun, and hears bird song. Immediately after this she approaches a fountain for a drink of water and believes the ghoul steps up toward her next the fountain, but instead it is only an older man.

Mary's American drama, as noted above, is the trauma of the outsider who has no home because there is no real grounding within what purports to be the normalcy of human society and its constructs. So it makes sense that it's when she's in the park, in a natural setting, that she's able to reconnect.

I'm going to skip over Mary's meeting a doctor with whom she talks about her experience, and then going out to Saltair to explore its mysterious attraction for her, except to step back to my remark on the natural alienation with the environment, for Saltair is an exception. As Mary explores Saltair she is confronted several times with the movement of inanimate objects. Perhaps we're expected to think this is caused by phantoms, I imagine we are, but these movements seem also unrelated to the ghouls Mary will see, even if Harvey intended a connection. Instead, in a manner that hasn't much to do with a basic horror-ghost story, objects moving by themselves becomes more a way of enlivening the environment. Saltair responds to her presence whereas the city was oblivious to her.

That evening she returns to the church to practice, where our first shot is from the interior of the swell cabinet of the pipe organ, as the shutters of the swell cabinet open and we observe Mary at the organ on the opposite side of the balcony. This may remind of when John earlier spied on Mary when she changed out of a towel into her robe.

The swell shutters open giving us a view of Mary at the organ.

The swell shutters open giving us a view of Mary at the organ.

View from behind Mary of the open swell cabinet.

View from behind Mary of the open swell cabinet.

As we view Mary playing the organ, we are initially returned to the stained glass window of the blind, then see the third window, which completes the set of windows on the balcony. It is titled, "And to Cast Out devlls."

The "And to Cast Out Devils" window in the church

The "And to Cast Out Devils" window in the church

Image from "The Stained Glass Windows of Trinity Episcopal Church, Lawrence, Kansas"

Image from "The Stained Glass Windows of Trinity Episcopal Church, Lawrence, Kansas"

showing the "And to Cast Out Devils" window

Shot of Mary playing the organ following the "And to Cast Out Devils" close-up

Shot of Mary playing the organ following the "And to Cast Out Devils" close-up

Just as John and his blind eye doubled the window on the healing of the blind, this time Harvey shows Mary's bare feet operating the pedals of the organ, a doubling of the bare feet in the "And to Cast Out Devils" window. As Mary plays, she is herself surprised by how the music becomes discordant, as if her conscious mind has no part in what flows from her fingers. We view a number of ghouls gather in the Saltair pavilion where they dance to the music she plays at the church. The ghoul who has several times already confronted her, parts from the group and approaches the camera, arms extended as if to grab us or Mary. The ghoul becomes the priest grabbing Mary's hands as she plays and stopping her.

The ghoul approaches Mary as she plays, it at Saltair, she in the church

The ghoul approaches Mary as she plays, it at Saltair, she in the church

Instead of the ghoul laying hands on Mary, it is the priest

Instead of the ghoul laying hands on Mary, it is the priest

The priest cries out, "Profane! Sacrilege! What are you playing in this church? Have you no respect? Do you feel no reverence? And I feel sorry for you and your lack of soul. This organ, the music of this church, these things have meaning and significance to us. I assumed they did to you. But without this awareness, I'm afraid you cannot be our organist." He asks her to resign, then tells her, as she leaves, distraught, that she's not being abandoned, and she shouldn't turn her back on the church.

This scene has completed showing us the three windows of this area. Their titles, put together, read, "To have power, to heal sickness, and to cast out devils". This is a condensing and rephrasing of the New Testament's Matthew 10:1 and Matthew 10:7-8.

Matthew 10:1

And when he had called unto him his twelve disciples, he gave them power against unclean spirits, to cast them out, and to heal all manner of sickness and all manner of disease.

Matthew 10:7-8

7 And as ye go, preach, saying, The kingdom of heaven is at hand. 8 Heal the sick, cleanse the lepers, raise the dead, cast out devils: freely ye have received, freely give.

Matthew 10:7-8 includes the injunction to raise the dead.

The below is an excerpt from the play Herk had directed in 1949, Irwin Shaw's Bury the Dead.

PRIEST: The old demons have come back to possess the earth. We are lost...

A YOUNG WOMAN's VOICE: (Very strong.) The dead have arisen, now let the living rise, singing!

BUSINESSMAN: Do something, for the love of God, do something...

PRIEST: We will do something.

A YOUNG MAN: (Insolent.) Who are you?

PRIEST: We are the church and the voice of God. Those corpses are possessed by the devil, who plagues the lives of men. The church will exorcise the devil from these men, according to its ancient rite, and they will lie down in their graves like children to a pleasant sleep, rising no more to trouble the world of living men. The church which is the voice of God upon this earth, Amen. I exorcise thee, unclean spirit, in the name of Jesus Christ; tremble, O Satan, thou enemy of the faith, thou foe of mankind, who hast brought death into the world, who hast deprived men of life, and hast rebelled against justice, thou seducer of mankind, thou root of evil, thou source of avarice, discord, and envy.

SOURCE: Irwin Shaw's Bury the Dead

The situation of the dead-alive soldiers in Bury the Dead reminds of Mary's with her having risen from waters of the river and now being thrown out of the church with her playing music that is considered not harmonious enough to be sacred. In the play, a young woman feels that the soldiers having risen from the dead is a call for rejoicing, but the priest condemns them as unclean spirits, possessed by the devil. Are we to look upon Mary as one who has risen from the dead as in a miracle, resurrected, or as one who is as a devil?

Stunned by the priest's rejection, Mary keeps a prearranged date she'd made with John Linden. When they return to the rooming house, eager to not be alone with her fears, she permits John in her rooms even while she attempts to avoid his advances. As she stands before her mirror, he approaches from behind and attempts to kiss her, then we see in the mirror what Mary sees and that it is instead the ghoul who is beside her. She screams and turns and in the next shot we see that John is actually standing back beside the bed. It seems he'd not approached and kissed her before the mirror after all.

Mary before the mirror in her room, John seeming to embrace her

Mary before the mirror in her room, John seeming to embrace her

Mary before the mirror in her room, the ghoul is seen instead of John

Mary before the mirror in her room, the ghoul is seen instead of John

Mary turns away from the mirror toward John who is actually standing beside the bed

Mary turns away from the mirror toward John who is actually standing beside the bed

Unnerved by Mary's scream, John leaves, and she starts pushing furniture before doors to protect herself. From outside we have a view of what is supposedly her window. It's a composite of three and is partly stained glass, and it may be we are intended to make a connection with the church and its windows.

Stained glass windows of Mary's apartment

Stained glass windows of Mary's apartment

When Mary tries to leave Salt Lake City, her car breaks down. She takes it in to be fixed and while she is waiting the ghoul pursues her so she attempts to flee on foot, in another state of dissociation. Unable to escape the city, she finds herself again in the park, where she is able to reconnect, as she did the day she'd gone shopping for her dress. She returns to the doctor but he becomes a ghoul and she is startled awake in the car. This part has all been a dream. As one sleepwalking, she returns to Saltair...where she will vanish.

The opening scenes, the plunge into the river, Mary climbing out of it after three hours, are essential. The final one of Mary being found in the car isn't. The film would have been every bit as effective if it had ended with Mary's disappearance on the beach. Eurydice had been snatched back into the underworld.

The soundtrack. When I now watch Carnival of Souls, I realize how much of a silent film it is, the organist, Gene Moore, not only supplying the oft-noted eerie music, but commenting on the action with other moods, even with a touch of comedy when applicable. Unlike other films, the story was written so that the music, all organ, was more than background, it became at times also the voice of the other world as well as Mary's. And I can't, off the top of my head, think of any other film in which the music has been integrated in a remotely similar way. When one watches the deleted scenes one appreciates that, in respect of dialogue, the sparer the better, that this is a film about Mary's anxiety, her emotional state. Her dissociation. Her panic. Her inability to understand what is transpiring.

A FEW MORE NOTES BEFORE CONTINUING

One thing I remember I decided as a writer was, I wouldn't give this heroine any help. Usually a man comes in, if a woman's in any trouble, in those old films, always some fella comes in and helps her solve her problem, but most of the men in Carnival of Souls are heels and slobs. And she doesn't...get really any help. Doctors try to help her but they don't quite understand either. Never makes contact. I saw her as somebody who isn't making contact with the world anymore, for whatever reason, I leave it to your imagination.

John Clifford Interview, 1999, Demolition Kitchen Video

Ultimately I wound up first in New Guinea—in Finschhafen, New Guinea. Then we moved up to Hollandia and built our first hospital...We got some of the wounded from New Guinea there, but basically I think they were preparing to invade the Philippines. In the invasion of the Philippines, they threw a lot of the heavy wounded down to us...In the hospital and stuff, I saw a lot of the real terrible things, you know, they don't show in newspapers, things like that. It affected me a lot, I think...Then we followed them up to the Philippines...we sailed up there on that little hospital ship...and I remember arriving at Manila Bay and they were still fighting on the far edges of the city of Manila and...the whole bay was full of sunken ships, all you'd see was these masts sticking up, and I remember that sight. You don't know what's below the water, what kind of ships, you see these masts.

...

You know, you don’t know what’s getting on your nerves. You don’t show your nerves in the Army. I think when the war ended, and the war was over, and they started sendin’ them back by the numbers, I had been in then almost… goin’ on almost five years—four years and eight months or somethin’ like that. But somebody decided that our hospital was stayin’—that we had to stay at different jobs, had to stay longer. I stayed for about four more months there, and I think that was the hardest months for me, ’cause I was replaced in my job, and I had nothing to do, and I couldn’t go home. So when I got home…. I didn’t know it, but when I came back to the States…. I came back to Kansas, and I’ve been pretty much in Kansas ever since. My wife was livin’ in Kansas by that time. Her father had opened a shop in Emporia. But we went back to Hollywood briefly. But there was something wrong with me. I never heard of that post stress…I don’t know, but I…. All of a sudden we’d be [unintelligible], and I’d burst out cryin’, and I didn’t know why. One time I was standin’ on the street corner, and my heart just started racin’ like crazy. I thought I was havin’ a heart attack, and I went to a doctor. He examined me, and he says, “[If] you’ve got a bad heart, I’ll eat it.” He asked me what I was doing, and I told him I was then going to a Hollywood school for writers, and I was working in an orange juice factory, and I was trying to write things and make some money. He said, “Well, I’m gettin’ more veterans. You’re tryin’ to make up for all that lost time” was the way he put it, I think. He didn’t really have the explanation for stress we have now...

John Clifford WWII Interview, August 18 2007, Veterans oral history, Kansas Memory

The Battle of Manila ( 3 February – 3 March 1945) was a major battle of the Philippine campaign of 1944–45, during the Second World War. It was fought by forces from both the United States and the Philippines against Japanese troops in Manila, the capital city of the Philippines. The month-long battle, which resulted in the death of over 100,000 civilians and the complete devastation of the city, was the scene of the worst urban fighting fought by American forces in the Pacific theater. Japanese forces committed mass murder against Filipino civilians during the battle and American firepower killed many people. Japanese resistance and American artillery also destroyed much of Manila's architectural and cultural heritage dating back to the city's founding. Manila became one of the most devastated capital cities during the entire war, alongside Berlin and Warsaw.

Source: Wikipedia

For the white Australian and American (and some African American) troops who fought there, New Guinea was one of the most horrific battlegrounds of World War II. Dense jungles, intense heat, disease, and fierce Japanese resistance all combined to make service on the island—the second largest in the world—a misery. And it lasted a long time: From March 8, 1942, when Japanese forces first landed on the island, to the end of World War II in the summer of 1945, fighting took place across the island of New Guinea and in its nearby island chains. The worst suffering, though, was endured by the indigenous peoples of New Guinea...

Source: The National WWII Museum

MARY HENRY AS A TRAUMA SURVIVOR

Throughout, while working on this analysis, I was having a problem with a layer of the film that was profoundly muddying the waters, and that was though Mary Henry's condition was supposedly due her rising from the dead and being disconnected from the world as she no longer belonged in it, I felt she was dissociated from it for another reason. She was exhibiting all the signs of a survivor of trauma, which is why it was important to me to have found that one of the deleted scenes has the individuals at the organ factory discussing how Mary has always been this way, though seeming stranger after the accident.

When she leaves the organ factory, Mary rather bitterly, defiantly remarks that she will never be "coming back", after relating that on the way to her new job she won't be visiting her family either. This reads that Mary has past history.

At first, I thought I would skip examining this aspect and stick to Eurydice, then reconsidered and decided to discuss the trauma in a separate section. While reflecting on how I would do this, I tracked back and began gathering together what I considered to be some of the more important quotes that I'd read or heard in interviews so that I might include them verbatim. So doing, I was also trying to sort out who was responsible for what in the film. Herk Harvey had found Saltair and had a vision of people ghostly dancing in its abandoned pavilion. The San Francisco Examiner states he and John Clifford crafted an outline together, Clifford seemingly the one however to come up with the character of Mary as an organist. Clifford in another interview stated that he did a draft, Harvey made some changes, Clifford completed the script, and that while filming Harvey sometimes improvised. Harvey states that it was Clifford who came up with the idea of Mary becoming dissociated from the world around her, unable to hear it, and the world unable to see her.

Searching through Harvey-Clifford interviews for quotes and more information, I found mention of one the film magazines who had first written on Carnival of Souls. When I couldn't find anything further on it, I tried looking the article up on the internet archive. Rather than locating the article, I came across the 1999 solo interview with John Clifford on the making of the movie, and then the interview he had given on his experiences in WWII. I listened to literally at least a couple of hundred such interviews with Vietnam veterans when I was doing research for my analysis on Full Metal Jacket. Many of them were very open about their trauma. Had Clifford been in a position wherein he might experience trauma? And if he had would he talk about it, or as a member of the Great Generation would he avoid the subject? As it turned out, though he wasn't ever in battle, his work put him in the position of dealing with the brutal results of war in a hospital situation, and in the Philippines the sounds of battle were routinely heard. In his WWII interview he gives a brief description of how, returning home after five years of service, he found himself unable to cope with bewildering emotions, crying for no apparent reason, experiencing panic so extreme he thought he was having a heart attack. The doctor he saw didn't understand, he only knew that he was seeing other veterans in the same situation and he interpreted it as due their trying to make up for lost time.

Until relatively recently, the effects of trauma were little comprehended. Then post-Vietnam a name was put to the life-altering effects of trauma--Post Traumatic Stress Disorder--and somehow the naming of it meant acceptance and the beginning of a reckoning. When Clifford gave his interview in 2007, he was by then well-acquainted with PTSD and the fact he had suffered from it as a veteran of WWII, a person who had seen things he didn't want to describe. PTSD affects every aspect of one's life. It's inescapable. It haunts. It stalks. One wakes up screaming. It isolates one from the rest of the world. This was at first understood as happening only to survivors of extreme situations, such as war, but in the 1980s, as a survivor of long-term childhood/adolescent trauma, I understood I was experiencing the same symptoms as veterans, long before anyone began to talk about a form of PTSD applying also to victims of chronic trauma. I'm getting personal here because of the peculiar thing Clifford did with his experience of PTSD, before he knew it was PTSD, an inescapable nightmare that relentlessly pursued one everywhere, which would cause one to dissociate and create a terrible sense of isolation. I don't know why, but the decision was made to have a woman, Mary Henry, undergoing this experience in Carnival of Souls. For Mary, the trauma of a car accident precipitated it. But with death becoming a man stalking her, her experiences fit the description of a woman who's survived other forms of trauma, such as communicated when it seems John comes up behind her to kiss her but she screams as he becomes the ghoul. This is what makes for so many confusing layers in Carnival of Souls. Forget about Mary and the river. The dissociation she's feeling is Clifford's PTSD.

Mary Henry is a survivor of trauma who is alienated from others, who has tried to muscle her way through life, counted herself as strong and capable, a realist, but you can't outrun trauma. For some reason Clifford expressed his PTSD in a woman who can seem as if she's pursued by the trauma of some kind of sexual assault, which means he understood.

She's a woman who meets up with a doctor who does tell her he believes her recent trauma is causing her distress, he wants to help, but doesn't know how to do so, just as Cliffords doctor after WWII didn't know how to really help him.

In some ways, it feels like an invasion of privacy to look at Clifford's life and see how it would have impacted Mary Henry, who in 1961 couldn't escape her trauma--and I don't want to leave out how Clifford talks appreciatively of his decades at Centron, how he didn't like how writing is an isolating profession but at Centron he had companionship, enjoying the commotion of several projects going at once in different stages of development. But John Clifford's WWII interview is open enough that one knows he felt it important to talk about PTSD and how it was not understood when he came out of WWII. I wouldn't explore this if it wasn't for that interview.

AND JUST A FEW MORE QUOTES

BEFORE FINISHING UP

"You borrow from everybody. People tell me well they stole that from Carnival of Souls. It doesn't bother me. We all learn from each other."

John Clifford, writer of Carnival of Souls, 1997 interview

Certainly, the antipathy of the surrealists towards Cocteau is an indisputable fact; and yet certain critics, and notably V. Weisstein, have tended to see Cocteau as a champion of surrealism. There is in fact very little evidence in Cocteau's Oeuvres Completes to suggest that he could in any way be identified with the surrealist movement as established by Breton. Indeed, if the killing of the pantomime horse in Orphee (1925) had any direct symbolic significance, it was surely the rejection in 1925 of all aspects of facile, gratuitous novelty and mystification with Cocteau associated with the spontaneous, automatic act of the early surrealist movement. Automatic creation was impossible for Cocteau at a period when he had discovered within himself the need to escape all forms of gratuitous excess in favour of discipline and controlled expression in art; surrealism itself was impossible.

But to be or not to be a surrealist in 1925 was not really the question for Cocteau.

Certainly Orphee was proof enough, as indeed was Plain-Chant, that in Cocteau's world of poetry, the time-space barriers may be easily overcome. Life and death, reality and dream, "le communicable et l'incommunicable" of Breton were embraced by the poet in one single vision. To this extent, Cocteau was still as much a "Surrealist" in 1925 as he had been in 1917. But he was a surrealist without a school.

Source: Bancroft, David. “Cocteau’s Creative Crisis, 1925-1929; Bremond, Chirico, and Proust.” The French Review, vol. 45, no. 1, 1971, pp. 9–19. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/385687

If the Great War was not the creator of the surrealist movement, it was certainly its catalyst. The majority of future surrealists, writers or artists, were part of the war generation. Joe Bousquet, like Paul Eluard, fought on one side of the trenches; Max Ernst on the other. And it was the war poet Guillaume Apollinaire who invented the term 'surrealism' in his 1916 play, Les Mamelles de Tiresias. It is striking to note other links between the war and the history of the surrealists. Andre Breton, Theodore Fraenkel and Louis Aragon served as doctors or orderlies in the medical services which treated physically and psychologically disabled men...Can we locate in the slaughter of 1914-1918 the origins of the surrealist vision of the dismembered body and soul, their familiarity with slaughterhouses, both real and symbolic? During the second world war, Andre Breton wrote that surrealism was defined by its relation to the two wars. 'Surrealism in effect was the only intellectual movement which succeeded in covering the distance separating them.' 'I insist', he noted, 'on the fact that surrealism cannot be understood historically without reference to war--I would say from 1918 to 1938--both the war it left behind and the one to which it returned.'

Becker, Annette. “The Avant-Garde, Madness and the Great War.” Journal of Contemporary History, vol. 35, no. 1, 2000, pp. 71–84. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/261182.

THE BIRTH OF SURREALISM AND ITS RELATIONSHIP TO CARNIVAL OF SOULS AND

THE CHILDREN OF THE BOMB

In a couple of interviews, John Clifford relates his theory about the popularity of the movie especially with young adults and youth, He believes it's because their futures are uncertain to them, as with Mary. My inclination is to outright reject this, but for all I know he may be right about some individuals. However, there were plenty of films in which an uncertainty over the future was communicated, with which young adults could empathize. Though Clifford stated he wasn't "arty", but when talking about how Carnival of Souls was dismissively received at its premiere in Lawrence, Kansas he supposes that had they made a straightforward film it would be welcomed as it would be proof they knew how to make a real film, that they hadn't that confidence with a film more adventurous, experimental, atypical (that's my paraphrasing). When it gained popularity with youth in later years, Clifford wondered if it was because of Mary Henry's alienation, and felt it said something about youth becoming increasingly alienated. So he had two theories (at least voiced in interviews) about the film's popularity with youth, and the problem with each is that other films communicated uncertainty and alienation. He perhaps had other thoughts but these theories were succinct and easy to communicate in an interview.

Youth and young people empathized with the alienation and uncertainty, but that doesn't account for Carnival of Souls having attained cult popularity. Carnival of Souls became a cult film, but not every cult film influences filmmakers.

Herk Harvey was profoundly influenced by Cocteau's films and speaks of this in interviews, giving himself as especially impacted by Cocteau's 1930 Blood of a Poet. Hardcore by-the-book surrealists/automatists might not honor Carnival of Souls as surrealist, just as Cocteau wasn't accepted by Andre Breton as a surrealist, but the surrealism of Breton's 1924 manifesto wasn't the same as that of his inspiration, Guillaume Apollinaire, who had coined the phrase in 1917 when writing about his play, Les Mamelles de Tiresias: Drame surréaliste (The Breasts of Tiresias) and Cocteau's Parade. Apollinaire died in 1918 and Breton picked up the term. Surrealism became a school, which began fractioning almost immediately.

At Saltair in Carnival of Souls

At Saltair in Carnival of Souls

Danger of Death - The hermaphrodite in Cocteau's Blood of a Poet

Danger of Death - The hermaphrodite in Cocteau's Blood of a Poet

Many of the original surrealists were medics in WWI, just as John Clifford was a medic in WWII. They dealt with shattered bodies and lives. They went home to deal with their own psychic dismemberment.

Herk (Harold) Harvey also served in the Navy as a Quartermaster, and though I can't locate much information on this I do see that he was on the ship, Castor, in January of 1944 when it sailed from San Francisco to "unknown". Wikipedia states that "From January 1944, her voyages from the west coast were to bases in the Marshall Islands, and after a brief overhaul at Seattle, Washington, Castor reported at Manus 18 September for duty with famed task force TF 58. Operating primarily from Manus (New Guinea) and Ulithi, she replenished the fast carrier task force at sea thus helping to expedite the smashing series of raids which pushed the Japanese ever westward. The final phase of these operations found the cargo ship acting in support of the assault on Okinawa, off which she operated through May and June 1945.." Whatever were Harvey's experiences in the war, I don't know, but I've noted how in 1949 he directed Irwin Shaw's play, Bury the Dead, in which soldiers refuse to be buried.

What were some of the perspectives on the traumatized individuals heading home from WWI? I'm going to quote extensively below from what I feel is a very relevant paper, as regards Mary Henry, and Apollinaire's Les Mamelles de Tiresias. Wikipedia succinctly notes of it, "Inspired by the story of the Theban soothsayer Teiresias, the author inverted the myth to produce a provocative interpretation with feminist and pacifist elements. He tells the story of Therese, who changes her sex to obtain power among men, with the aim of changing customs, subverting the past, and establishing equality between the sexes."

According to spiritualists, such [war time] terrors survived even after death. Given the abhorrent nature of warfare, it is perhaps correct to argue with two researchers from the University of Manchester just after the war that shell-shocked men were not those who had lost their reason. Rather, their senses were 'functioning with painful efficiency'.

Although in the examples just given, the trauma was related to killing, these men were not "typical' psychiatric casualties. Most soldiers who collapsed never killed anyone. As Lieutenant-General Sir Charles Burrchaell told the Royal Academy of Medicine in 1920, men broke down despite never being in the firing line. He was not surprised by this, explaining that this was "only to be expected seeing that a large number of men who joined the Army were temperamentally unfitted for a soldier's life. Such men got into a nervous state before they came under fire." Furthermore, as I argue elsewhere, Medical Officers at the front were forced to recognize that more men broke down in war because they were not allowed to kill than collapsed under the strain of killing. What was unbearable about modern warfare was its passivity in the midst of extreme danger. As Tom Kettle (Young Irelander and Lieutenant in the Dublin Fusiliers) lamented in 1917: "In the trenches death is random, illogical, devoid of principle. One is shot not on sight, but on blindness, out of sight." Or, in the words of the prominent psychiatrist John T. MacCurdy in War Neuroses (1918), modern warfare was more psychologically difficult than warfare in the past because the men had to "remain for days, weeks, even months, in a narrow trench or stuffy dugout, exposed to constant danger of the most fearful kind...which comes from some unseen source, and against which no personal agility or wit is of any avail." This, coupled with the fact that hand-to-hand fighting was rare, meant that many men never had "a chance to retaliate in a personal way". It was their enforced passivity that was emotionally incapacitating.

...

Despite the unique frightfulness associated with modern, technology-driven warfare, it was widely accepted that the "abnormal" men were those who were repelled by wartime violence. These men had to be cured: that is, they had to rediscover their "natural", masculine bellicosity. The assumption that it was normal for men to act extremely aggressively can be illustrated in numerous ways. For instance, in his classic textbook, War Neuroses (1918), John T. MacCurdy described the suffering of one twenty-year-old private. MacCurdy noted that although this soldier had not exhibited "neurotic symptoms" before the war, he still 'showed a tendency to abnormality in his make-up'. "...rather tender-hearted and never liked to see animals killed..."

...

In other words, "normal" men were psychologically capable of killing because they were tough, did not mind seeing animals slaughtered, were gregarious and mischievous as youths, and were actively heterosexual...Psychologically abnormal men were those who tended to 'return to the mental attitudes of civilian life' and were therefore unable to cope with the horrors of combat. They were "childish and infantile" and needed to regain their "manhood". Most important, such men had to be 'induced' to face their illness "in a manly way". According to the London Regional Director of the Ministry of Pensions, they needed not so much a psychiatrist or neurologist as a "good fellow with a kindly eye and manner and with a good square chin--a man in short who can and will command the respect of the patients as a man".

Bourke, Joanna. “Effeminacy, Ethnicity and the End of Trauma: The Sufferings of ‘Shell-Shocked’ Men in Great Britain and Ireland, 1914-39.” Journal of Contemporary History, vol. 35, no. 1, 2000, pp. 57–69. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/261181.

Apollinaire's play, though produced in 1917, was written in 1903, prewar, and in a preface he stated the surrealist satire had to do with the problem of repopulation. Regardless the subject, the woman rids herself of female characteristics and, feeling more "virile" than ever, goes to war, while the husband, remaining behind, takes on the "effeminate" role and has thousands of children. I've already hazarded that as Mary Henry first sees the ghoul in her own reflection, we may have two parts of a whole. She may not be directly compared to the male WWI soldier suffering PTSD, viewed as effeminate, and she may not be directly compared to Apollinaire's Therese/Tireseas, but she relates to them both. As perhaps an expression of John Clifford's trauma (he certainly wrote his trauma into her), the victim becomes a woman who is strong and self-reliant, but is also one who is suffering, struggling to confront what haunts her, but is unable to do it on her own. The priest is unable to help her, as is the doctor, however sympathetic he attempted to be. In light of trauma survivors having been viewed as failed men, she becomes a rectification of that misogynistic and emasculating stereotyping. That feminine aspect is instead a person of strength, yet still a sufferer. As I've already posited, she is the Eurydice who attempts to save herself but can't.

We can see in the following part of John Clifford's interview on his experience as a WWII veteran, the guilt of not being the one on the frontline, the survivor, the denial and repression of one's own fears because one wasn't killed, wasn't injured. He begins to recount his memories of hearing about the horror of the atomic bomb, but it is a subject that he pulls back from, except to acknowledge it was exceptional.

John Clifford: Oh, you know, I felt…. I appreciated the fact that I wasn’t up on the front line. So there’s always that contrast. You’re dealin’ with these fellows that had been there, so [you felt] “What am I afraid of?” I mean, if the other side was winnin’, there’d have been a different situation. I remember…. One of my memories, I remember hearing about Hiroshima and the atomic bomb.

Interviewer: Where were you when that happened?

John Clifford: I was in the Philippines, in our hospital…working in a hospital there. I remember realizing that humanity has turned some kind of a corner here. I mean, you can’t put…. You’re not going to be able to put that back in the bag. I hoped, like many people did, that it meant the end of war. But, you know….

Interviewer: Well, you know, that’s just it. I grew up with all of this. But this was somethin’ that was very new. I mean, you had nothing to base it on when they said how big that bomb was.

John Clifford WWII Interview, August 18 2007, Veterans oral history, Kansas Memory

With WWII and America's unleashing the atomic bomb, a horror of a rather different stripe from WWI was brought home. Why did so many youth and young adults relate to Carnival of Souls? I reason it's because they found in its surrealist expression of Mary's pain their own trauma. They may not have been soldiers, but they were like the trapped soldiers of WWI who were ever in danger of being "shot not on sight, but on blindness, out of sight", impersonal casualties of the bomb. There was nowhere to run or hide. Carnival of Souls communicated this, the same trauma of the WWI medics who became the surrealists. Clifford communicated this with his own experience of WWII, the new weaponry of which escalated the business of killing from a localized affair to arms that could manifest near numberless casualties and poison the world. The children of the bomb were now under continual, inescapable threat, and science and religion failed them with an inability to deal with threat of personal annihilation as well as global.

At Saltair, the doctor and the priest puzzle over Mary's disappearance

At Saltair, the doctor and the priest puzzle over Mary's disappearance

Whether intentional or not, Herk Harvey and John Clifford had captured their anxieties in the plight of Mary Henry.The children of the bomb glimpsed their new alienation in her. John Clifford's wondering if she expressed youthful uncertainty in the future was not the matter of simple bewilderment at navigating the world as an adult, the uncertainty in the future was instead the daily, communal experience of not knowing whether there would be a future. The typical horror film provided an enemy from which one could run, against which the hero or heroine had an opportunity at victory. The surreal treatment of the psychological horror of Carnival of Souls instead gave expression to the reality of existential dread and the alienation of helplessness.

June 2023. Approx 12,400 words or about 25 single-spaced pages.

Return to top of page

Link to the index page for all the analyses