Homer Moulthrop and the Hanford Project’s Plastic Man

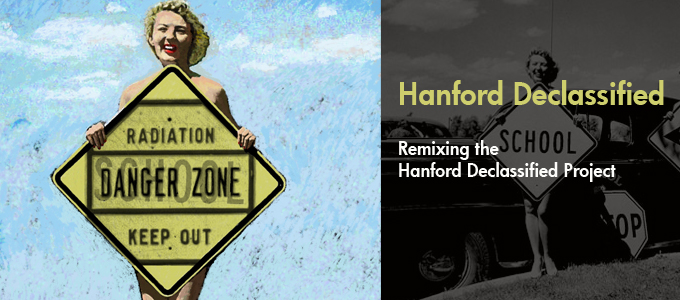

A couple of weeks ago, I suggested to the always interesting website Retronaut that photos of Plastic Man, from the Hanford declassified archive, might be of suitable interest to them and readers, and a few were posted. Plastic Man remains one of the more curious looking Hanford creations, though society is a few generations beyond being accustomed to the appearance and necessity of protective gear. Plastic Man was and remains a curiosity because he was a futuristic collision with farmers and sheep ranchers. He promised clean, safe energy while so hidden in his protective suit that his individual humanity was easily displaced by that which shielded him from radiation contamination. Several years ago I put up this blog post on that collision, with photos of him, and had also done a digital painting based on a photo from the early Richland Atomic Frontier parades in which he was featured on a float (see prior link).

Recently going through the archives again, within the last two weeks I came across a photo of Plastic Man coupled with then name Homer Moulthrop. No explanation was given, and the name Homer Moulthrop wasn’t consistent, sometimes spelled differently.

Shortly thereafter I found in the April 5, 1954 issue of “Life” magazine an article on Homer Moulthrop, who turns out to have been the creator of Plastic Man.

Plastic Man is also weirdly endearing because of the unwieldy appearance of the suit, presenting the appearance of a plastic toddler, muscles not yet finely tuned, legs stiff and splayed. In certain poses he looks as though he should be playing with blocks, and was perhaps less alarming than amusing, though we shall see below he was dubbed Homer’s Hideous Hallucination.

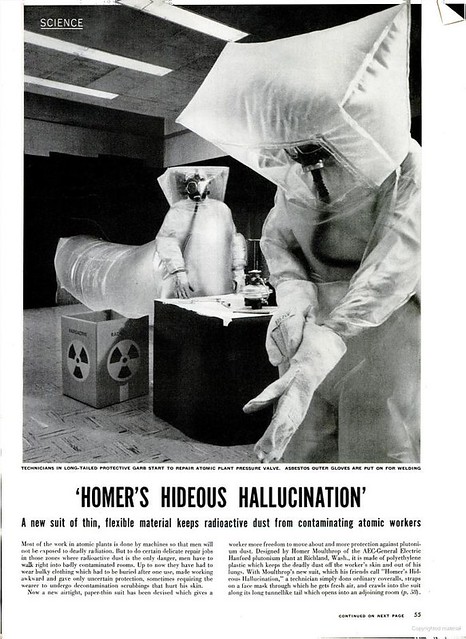

Pg. 55

Technicians in long-tailed protective garb start to repair atomic plant pressure valve. Asbestos outer gloves are put on for welding.

‘Homer’s Hideous Hallucination’

A new suit of thin, flexible material keeps radioactive dust from contaminating atomic workers

Most of the work in atomic plants is done by machines so that men will not be exposed to deadly radiation. But to do certain delicate repair jobs in those zones where radioactive dust is the only danger, men have to walk right into badly contaminated rooms. Up to now they have had to wear bulky clothing which had to be buried after one use, made working awkward and gave only uncertain protection, sometimes requiring the wearer to undergo decontamination scrubbings that hurt his skin.

Now a new airtight, paper-thin suit has been devised which gives a worker more freedom to move about and more protection against plutonium dust. Designed by Homer Moulthrop at the AEC-General Electric Hanford plutonium plant at Richland, Wash., it is made of polyethylene plastic which keeps the deadly dust off the worker’s skin and out of his lungs. With Moulthrop’s new suit, which his friends call “Homer’s Hideous Hallucination,” a technician simply dons ordinary overalls, straps on a face mask through which he gets fresh air, and cralws into the suit along its long tunnellike tail which opens into an adjoining room.

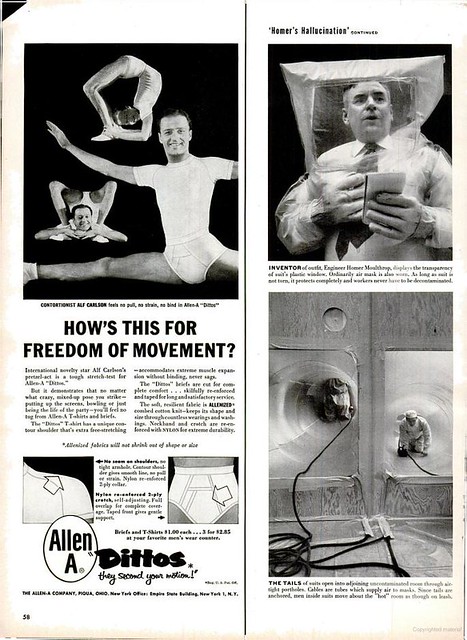

Pg. 56

Front of suit is made into shape of a man so that technician, here sitting as he slips his hands into suit’s built-in gloves, will fit easily into it.

Rear of suit is a 15-foot long hollow “tail,” down which worker crawls to enter. Suit stays inflated because air pressure in room is lower than in suit.

Pg. 58

Inventor of outfit, Engineer Homer Moulthrop, displays the transparency of suit’s plastic window. Ordinarily air mask is also worn. As long as suit is not torn, it protects completely and workers never have to be decontaminated.

The tails of suits open into adjoining uncontaminated room through airtight portholes. Cables are tubes which supply air to masks. Since tails are anchored, men inside suits move about the “hot” room as though on leash.

Perhaps we’ve a bit of intentional ad placement that beside Plastic Man is the advertisement for “How’s this for freedom of movement?” Ditto’s underwear, featuring a contortionist performing yoga-like moves.

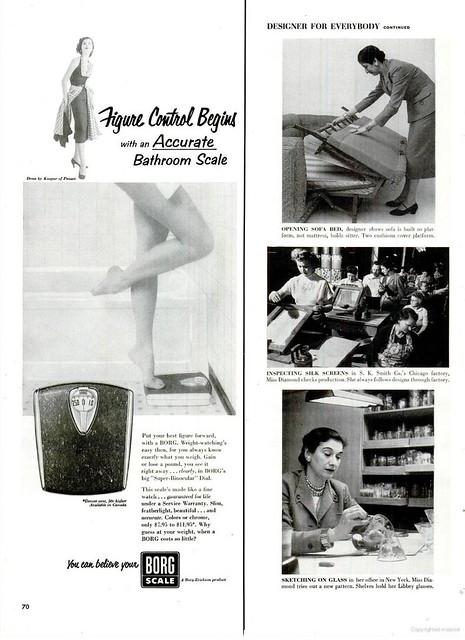

For the fun of it, sampling what else “Life” was featuring for their readers, here’s an article on designer Freda Diamond from the same issue.

Pg. 69

Designer for Everybody

Millions of U.S. Homes Profit by Her Good Taste

Freda Diamond has probably done more to get simple, well-styled furnishing into every room of the average U.S. home than any other designer. More than 25 million dozen of her glasses have been sold by Libbey during the past 12 years. Some 15 million of her kitchen canisters have been sold by Continental Can in the last four years. In the past 10 months more than 75,000 of her new wrought-iron pieces of furniture have been sold by Baumritter. A crusader for good taste in low-priced accessories and furniture, she has proved to manufacturers and store buyers that they were wrong in thinking inexpensive lamps, glasses, dinnerware, furniture had to be gaudy to sell. Her designs are popular enough to sell in dime stores, supermarkets and drugstores, yet distinctive enough to be exhibited repeatedly in museums.

Her 24 Latest

Freda Diamond sits behind cocktail table, about $20. On the table are decorated doorknob, $4.95 and matching accessories; oval desk basket of paper, $4.50; desk tray, $3; glass, 8 for $3.50 “coin” cigaret box, $1.25; scrapbook on floor, $2.25. At left is serving cart, $30. White dinnerware is $5.50 for 16 pieces; pattern is more. Table next to sofa is $20. Lamp, $25. Sofa bed is first of its kind (following page). Fabric window shade will cost from $5 to $10. Room divider (right) is $40. On it are glasses, dinnerware. Printed linen is expensive–$9 a yard. On floor are wastebaskets, $2.25; canister set, 89 cents; tray, 59 cents; address book, $2.50; guest book and photograph album are $2.25 each.

Opening sofa bed, designer shows sofa is built so platform, not mattress, holds sitter. Two cushions cover platform.

Inspecting silk screens in S. K. Smith Co.’s Chicago factory, Miss Diamond checks production. She always follows designs through factory.

Sketching on glass in her office in New York, Miss Diamond tries out a new pattern. Shelves hold her Libbey glasses.

Leave a Reply