Not like it’s an uncommon subject around here, but the other night Marty and I briefly discussed those big life changes where either through a sudden disruption or a slow, almost unnoticed disintegration, one opens one’s eyes to find that one is either on the edge or dead center of not just a spiritual but an organizational chaos where the old order of viewing, classifying and filing experience not only does not work but is absolutely hosed.

No, not an uncommon subject. We’ve discussed this for decades.

Marty believes everyone goes through this process and that it is a part of an essential reassessment that begins in the twenties. a growing up and beyond the world into which one has been indoctrinated, since birth, by parents and various institutions.

I agree in part, on a basic level, and have often enough watched people hit their mid to late twenties whose confidence suddenly wavers as they’re walking down the stairs of their apartment building, they’ve seen a glitch in the shadows off to the side, something’s not measuring up, not even if they believed they were well-formed independent thinkers, and they’re shaken by just how many little questions arise and inflate into giant dirigibles haunting the once familiar countryside.

But then again I don’t believe it is something everyone goes through…or should I say it isn’t an experience to which everyone submits (and Marty agrees with me on this more times than not so there is no “then again” or “on the other hand” about it, it’s just that sometimes he gives people more credit than I believe they deserve, just as he also insists that I often give people more credit than they deserve, one or the other depending on the weather). A good deal of fortitude is required, if one is deeply entrenched socially and career-wise in prefabricated boxes, to admit to re-evaluations that may risk laying waste those maps one accepted from youth as writ on stone, whatever the alphabet used.

I’m not just talking questioning authority. Questioning authority is a must and a good thing for all, yet a first step from which many recoil in mid stride, the dogs barking out all kinds of warnings of disasters to come considering the laws of falling dominoes. There’s a difference between a teenage rebelliousness that can easily morph into taking up the flag of the responsible status quo, and, in your twenties, thinking hard over a former seeming natural dispensation for Miracle Whip or mayo and finding there lies the slippery road to ruin. Nor am I talking Losing One’s Day Planner and waking up wondering, “Where am I?!” once or twice. But Losing One’s Day Planner once, then twice, then on the third time finding in its place a staff and cockleshell offers opportunity to resolutely flee the shadow of something greater before it decides you’re on friendly terms, the chances perhaps less than zero that without some personal initiative you’ll find yourself on a mountain, that staff now a lightning rod, the bolt that comes out of the blue leaving a whiff of both a scintillating and terrifying ozone in the scorched wake of which you now have all the time in the world to reflect on an infinite number of briefly illuminated seemingly relevant details, except you are badly burned and damned if you can remember why you were standing there in the first place.

I began trying to approach this some in the Penguin book–well, didn’t exactly begin there, as a couple plays of mine had this as their base as well as another previous book, but the Penguin novel took it a bit further and I have been hoping to work with this more in the book I’ve laboring on the past couple years.

In the Penguin book, the more boiled down relation of the process is via the giggly subatomic particles whose idea of the punch line of a good joke is miles beyond when you’re ready to lie down and have a good, refreshing nap.

There’s a reason why Dionysus, bearing the gift of the jolly wine (let’s not insist on literalism, which has caused lots of problems historically) is the god who causes people to slip prisons..is also a god who is torn asunder.

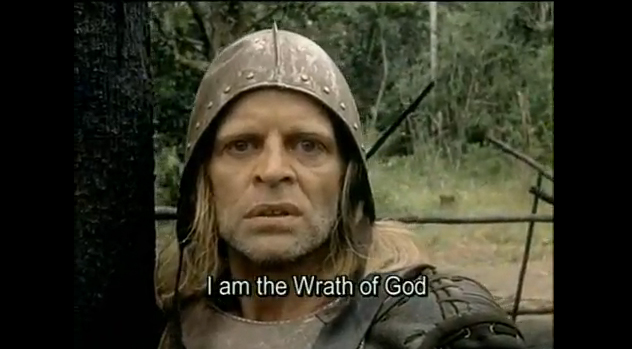

Thursday night, I watched Werner Herzog’s “Aguirre, the Wrath of God” again. The movie had been in the Netflix cue for a long while, and this past weekend I had viewed a good portion of Herzog’s “My Best Fiend” which had clips from “Aguirre” and reminded me that I’ve been planning for a year to watch it. What moved me, finally, to watch it on Netflix Thursday night was reading Jim McCulloch’s The Resonance of History, in which he relates some of his experiences while living in South America. He speaks of a period of his faith in science being unsettled following a brush with what might be described as an extra-personal yet all motivating breath (I can’t even palely paraphrase his beautiful, eloquent account)…and I don’t know how that resolved but he also mentions in contrast Cabeza de Vaca, who throughout his amazing (sometimes too incredible, for my money) wanderings in “The New World”, never lost faith in the institutions of his youth.

Had Cabeza lost faith then we’d not have visions of him crossing the desert, healing in the names of his Spanish gods, eventually followed by a crowd of hundreds of curious Indians. Jim recognizes a great story when he sees one, which he does in the barest details of Cabeza’s slim memoir, and beckons us to Picture in your mind this vast throng of diverse Indians walking through the desert toward the sunset, led by lean bearded men who healed in the name of the Jesus and the Virgin. Nothing like this had ever happened before, or has ever happened since.

What better promo for loyalty to one’s faith is that (would make a great movie, no?) and far more inviting than all those saints (old old world gods with little toes shorn off the better to fit them into new shoes) and their spurious martyrdoms urging devotion to a party which in its bullying literalism had more to do with divine right political leverage than revelation. “Admirable!” some would say. “Miraculous!” would say others. And I’m a little surprised Cabeza de Vaca wasn’t nominated for sainthood, except he was later critical about Old World treatment of the New World indigenous.

Still, though I am amazed by Cabeza de Vaca’s resilience and determination, eight years ago my gut reaction to reading his memoir was that his ability to cart the Old World along with him and persist in viewing all through its filter was not so marvelous as an astonishing blindness–unless he didn’t reveal in his memoir what he actually thought.

As Jim points out in his The Resonance of History, there were conquistadors who plunged into “The New World” claiming everything in sight for those old institutions, and people too who were instead conquered by “The New World”, some of whom may have eventually attempted to straddle both with a foot on each shore but it’s difficult to be in two places at once.

“Aguirre, the Wrath of God” concerns an expedition which stalls and, the expressed belief being that both hostile Indians and the fabled city of El Dorado are within a few days’ journey, an exploratory group is sent down river on several rafts, who are supposed to return with their report in the space of a week or be considered lost.

One of the great moments in “Aguirre, the Wrath of God” is toward the end when all on the last remaining raft, floating down the Amazon, weakened by hunger and illness, begin to suffer hallucinations.

The imposition of the Old World upon the New and the insanity of that aspiration has already been set up at the beginning the film. That known map, laid over the new, isn’t going to work, and we are awed with the crazed energy exerted, and enslaved, toward that effort. At first we are even sympathetic with Aguirre who seems to understand that the old institutions have no place here, such as in the scene where he comprehends the futility of the sacrifice required to retrieve from a raft on the far side of the river, in the trap of a whirlpool, the bodies of some of the party who have died, so that they may be carried home for a Christian burial on consecrated land. Aguirre, beginning to act on his own initiative, has the bodies blown up, which seems utterly sensible–or at least it does to me. But then, when he overthrows the Powers That Be, declaring independence (in essence, the first formal Declaration of Independence from the Old World of those transplanted to the new), as he forges ahead we find that he’s just as ruthless in his quest for power and fame, the gold of El Dorado inspiring others but despised by him and only useful as an inspiring tool.

But never mind right now the madness of Aguirre. Instead, here are the others on the raft, floating down the Amazon into chaos, moving further and further away from the old maps, unable to impose them on this new territory. Their new experiences would be difficult enough to chart, to make comprehensible; they are also now sick and hallucinating. What is real and what’s not, they’ve not a clue any longer, not too far removed from the trips of psychonauts. Eventually, the world of Maya is seemingly revealed, all is profoundly realized as illusory when there is witnessed a European boat with sail hanging high upon a tree (revisited in “Apocalypse Now” with the otherworldly plane and parachute encountered deep in the jungle, hanging in a tree). An individual pointing out the boat, the priest counters that the boat is but a hallucination caused by illness–which must be a mass hallucination as all view it. And Herzog permits the audience to see the boat, to participate in this seeming hallucination in a unifying transcendence delivered via his capable imagination and film and a meager $360,000 (or so) budget.

Row, row, row your boat, gently down the stream. Merrily, merrily, merrily, merrily, life is but a dream.

Fully comprehending now that nothing is as it seems to be, we see then the same individual voicing all is illusory, including the arrow that now appears in his leg.

The arrow, Aguirre points out, is real.

Which is to say that if you’ve climbed so high that you’ve stuck your head through the hole in the sky, then after having taken a little look around, it’s best to come back down and give Caesar the money that’s due him.

It’s said that once you’ve been there, there is no reason to ask why it’s best to climb back down.

Aguirre’s is a doomed journey, or at least it is for those who accompany him. All appear to die in the movie, including Aguirre’s daughter, though her death is unlike the others. As she stands facing the jungle at the end of the raft, Aguirre approaches and finds she has been pierced by an arrow. Yet we have the distinct feeling she hasn’t been slain by the same jungle as the others, Aguirre turning her so that we see the arrow (Aguirre, a real historical character, did eventually kill his daughter who had accompanied him on his final adventure). Aguirre’s raft now populated by a country of monkeys–and the dead–we circle round him as he at last vocalizes for us what has driven him, what still drives him, his vision of the world he remains intent upon founding.

Herzog makes no mention of it but the historical Aguirre’s title, as he began this not very famous journey, was “the keeper of the dead”. That was his capacity. He was to take charge over the possessions of those who died along the way.

Alot of people dying along the way, Aguirre was kind of like a self-made psychopomp, wasn’t he?

Herzog at one point has two indigenous emissaries approach the raft, a man and woman who relate their long anticipation of a golden god who, it was said, would come with smoking sticks (the guns) and complete the creation of the country. These two who come wearing gold have confused the blond Aguirre with that golden god, reminding of the mistaken notion that Moctezuma received Cortes as the returning Quetzalcoatl, that evidence of gold causing those on the raft to believe El Dorado is indeed near.

However, the raft upon which Aguirre floats also reminds of the Golden Boat of the El Dorado legend of the accession of new Musica chiefs, each known as the Gilded Man, who “went about all covered with powdered gold, as casually as if were powdered salt”. As part of the ritual of accession, the Gilded Man would ride upon a raft covered with gold objects to the center of a lagoon, and the center of the lagoon reached, the other chiefs signaling for silence, the Gilded Man would throw into the lagoon the gold in order to pacify its demon which was also their god.

The parent expedition, in a Herzog historical mash-up, is led by Pizarro, who seeing the fierce unnavigable rapids of the Amazon, insists that things will be smoother from here on out. Aguirre, looking at Pizarro like he is mad, counters that the river will consume all who venture in it. Which it does, Aguirre abetting as the self-styled Wrath of God. Aguirre may as well be the treacherous river, even to that end where he is unable to escape it in Herzog’s film.

We know, as does Pizarro, who sends the exploratory party on its way, that yes there will be hostile Indians but no El Dorado, and that yes the river will consume those who think it tamable as the horse that the party carries along with them, used to frighten the Indians. The horse is finally pitched off the raft on the order of Guzman in a pique of characteristic irritation, Guzman being the King of El Dorado who Aguirre has set up, given false purpose there in the jungle, Aguirre manufacturing for him even a makeshift throne. The horse tries to climb back on the raft but, unable, it struggles to the shore and stares out of the jungle after the raft like an Old World ghost, an omen of doom which Herzog shows Aguirre reflecting on but doesn’t reveal his thoughts, unless his feelings are divined in Guzman immediately being found strangled beside the outhouse.

The historical Aguirre trained stallions.

The historical Aguirre wholeheartedly confessed to killing Guzman. But Herzog doesn’t show this. He doesn’t show the source of a number of the deaths. The medium yes, but not the source. After the boat is sighted in the trees, one which we guess supposedly belonged to Francisco de Orellan (a lost explorer, another mission of this expedition being to look for any trace of what had happened to his party), it is Aguirre who interrupts the hallucinatory daze, reordering nature, reestablishing the divide between what is real and what is not, because Aguirre is like fate is like the Wrath of God is like the river and the jungle and every single indigenously flung arrow…and not the river at all, the river simply being what it is. A mad god, one begins to feel he has been there before and forgotten. When he goes to his daughter and turns her so we see the arrow in her belly, it is as though he has forgotten he was the bow and the hand which held it.

I don’t know where Herzog came up with this idea of the boat with sail observed hanging upon a tree, but we all of us wonder how, how, how did it get up there…perhaps the flooding river? Impossible, that it could reach up so high, but there is the boat, after all, there is the boat. Perhaps a little like other old world boats ferried by a wrathful god’s watery retribution to the highest mountaintops.

Who has been there before and what did they leave behind?

Some cultures more than others acknowledge, even if only through curious asides, the great shadow of the primordial elusive that may fall near one, a terrifying bird of prey that no one reputable person has seen but has been reported to snatch up the occasional unfortunate (there is this story) and spirit them away to its mountain top home, wherever that may be. The very breath of its wings is hallucinatory magic and can drive the unfortunate few, those without an institutional pillar to lean upon, to madness…or a fool’s journey. Don’t look if you can help it, but if you do, there are the curious asides left by those who have traveled before one.

When the fairy tales turn lively and say, “I hear you need someone to talk to,” it will very likely be at a place in the river between when something like Orellan’s boat appears in its tree and the mad, amnesiac Aguirre calls one’s attention to the reality of the arrows.

Leave a Reply