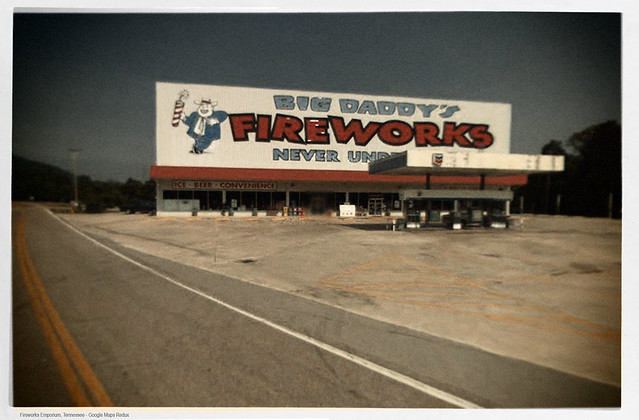

Fireworks Emporium Revisited, Tennessee – Google Maps Redux

The thrill and explosive, thunderous pizazz of colorful fireworks, which we Americans so closely associate with the clarion call of freedom and the 4th of July, but instead of a celebration of peace were probably more intended to recall and celebrate the “rockets red glare, the bombs bursting in air” of war. The first fireworks display I remember as a child was a 4th of July celebration in Seattle, the lights mirrored by the water beside which the show took place. My family considered fireworks to be dangerous and best overseen by professionals, perhaps partly due a great-grandfather of mine having lost an eye as a child to a fireworks accident (I never heard the whole story, only that it had happened and that he would baffle, amuse and frighten children by taking out his glass eye, this man who didn’t sound very funny but instead was a rather severe seeming patriarch). We only ever tried out sparklers a couple of times and I disliked them. The little beauty and excitement they provided wasn’t enough to make up for the smell and the undependable froth of sparks biting my hand. As soon as a sparkler was placed in my fingers I wanted to get rid of it. When I later met people for whom these state-line fireworks emporiums existed, who would stuff bags of them into their cars and carry them back to their homes, where they were illegal, I didn’t get it. To me, they were just an accident waiting to happen. What was the great thrill in the boom and the bang?

That eye of my great-grandfather, the glass one he would scoop out and with which he would terrorize children, I used to wonder what happened to it. Was he buried with that eye in its partner socket? Did someone in the family keep it as a reminder, and if so then to whom did it now belong? What color was its iris, blue or brown or hazel?

It seemed to me, writing Unending Wonders of a Subatomic World, that the novelty of a personal fireworks display was the kind of foundling, initiatory adventure Faith and Chance must have, celebrating their new freedom, escaping their lives and Georgia. I based the emporium on this one. Where nothing happened when Marty and I stopped at it once for gas. We had no adventure. But we stopped there because I knew that, eventually, Faith and Chance, hunting the Great Penguin, would stop there as well. But just because they would set off fireworks didn’t mean that I had to do so. My great-grandfather had lost his stereo vision because of fireworks, and that seemed like the kind of genetic history lesson that one minds. A kind of oracle. “Descendants. Do not tempt fate by doing as I did.” And I’m not into risking digits either.

Risk. I felt there was an element of risk basing a story around two young women running off to look for something as preposterous as a Great Penguin. Or at least that seeming the stapled on, purported goal of one of them. I didn’t worry about the scheme of the wanderers and their road trip being too hackneyed. I knew it wasn’t. That my story and the writing of it was original. But I was concerned that in a first blush brief scenario of a few sentences, it might appear hackneyed. “Two women undertake a road trip…”

“Oh, a road trip.”

“Yes, a road trip.”

Leave a Reply